Abstract

The transcription factor ΔFosB, a truncated splice isoform of FosB, accumulates in brain after several types of chronic stimulation. This accumulation is thought to be mediated by the unique stability of ΔFosB compared to all other Fos family proteins. The goal of the present study was to determine if the relative expression of the two fosB isoforms is also regulated at the mRNA level, thereby further contributing to the selective accumulation of ΔFosB after chronic stimulation. First, unlike the protein, the half-life of ΔfosB mRNA is only slightly longer than that of full-length fosB mRNA both in cultured cells in vitro and in the brain in vivo. Additionally, similar to c-fos, both fosB isoforms are induced abundantly in striatum after acute administration of amphetamine or stress, and partially desensitize after chronic exposures. Surprisingly, the relative ratio of ΔfosB to fosB mRNA increases most significantly after acute, not chronic, stimulation. Finally, overexpression of polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB1), which regulates RNA splicing, in cultured cells decreases the relative expression of ΔfosB compared to fosB mRNA. Together, these findings suggest that splicing of fosB pre-mRNA is regulated by the quantity of unspliced transcript available to the splicing machinery. Above a certain threshold of full-length fosB, determined by the amount of PTB1 or related proteins, the remaining primary transcript is alternatively spliced into ΔfosB. These data provide fundamental information concerning the generation of ΔfosB mRNA, and indicate that the selective accumulation of ΔFosB protein with chronic stimulation does not involve its preferential generation by RNA splicing.

Keywords: ΔFosB, PTB, splicing, drug addiction, stress, mRNA

1. Introduction

In 1990–1991, two groups demonstrated the induction of Fos and Jun family transcription factors in striatal brain regions after acute administration of cocaine or amphetamine13,44. Using a pan-Fos antibody, c-Fos and other Fos family proteins were shown to be transiently induced (2–4 hours) after a single drug injection, and degraded back to basal levels within 8–12 hours. This induction of Fos proteins was associated with the appearance of an activator protein-1 (AP-1) transcription factor complex. In 1992, we tested the effect of chronic cocaine on AP-1 induction, and demonstrated the persistence of an AP-1 complex for several days after chronic dosing compared to the several hour transient expression seen after acute drug administration18. This long-lived activity, originally termed the “chronic AP-1 complex,” was later determined to be composed of ΔFosB dimerized predominantly with JunD7,16,17,19,20. While JunD has a similar half-life to other Jun family proteins, ΔFosB was shown to exhibit an unusually long half-life compared to other all other members of the Fos family of transcription factors7,8,16,17,20.

ΔFosB, first identified in cultured cells9,33,43, is a truncated product of the fosB gene, which lacks the C-terminal 101 amino acids of the full-length FosB protein. Whereas other Fos proteins are induced rapidly and transiently in response to many types of acute stimuli, and return to basal levels within several hours, isoforms of ΔFosB are uniquely stable with in vivo half-lives estimated at weeks. As a result, after repeated stimulation, there is the gradual accumulation of stable 35–37 kD ΔFosB isoforms16,17,19,20. The literature is now replete with evidence demonstrating that these stable isoforms of ΔFosB are induced in a region-specific manner in brain in response to diverse types of chronic stimulisee 30,34. Moreover, this long-lived induction of ΔFosB has been associated with several forms of neural and behavioral plasticity related to drug addiction, stress responses, the clinical actions of psychotherapeutic drugs and electroconvulsive seizures, and certain lesions1,3,4,15-17,19-22,24,29,31,35,36,38,39,45. While several of these studies did not definitively establish that the FosB-like immunoreactivity observed is in fact ΔFosB, this interpretation is quite likely given the experimental conditions used.

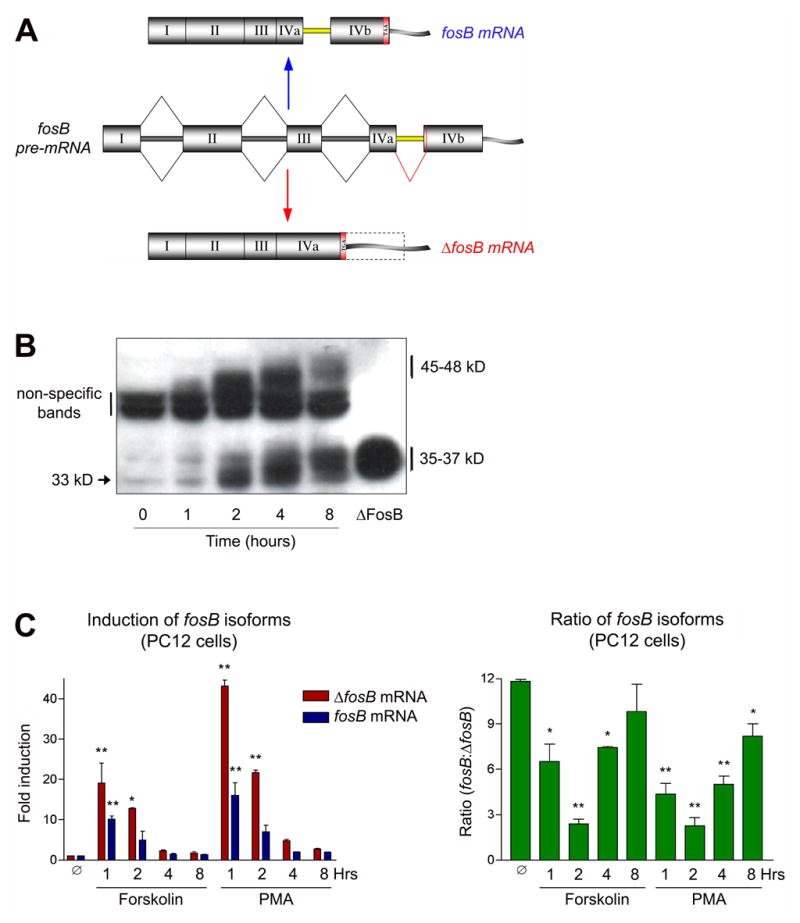

While the structure and post-translational modification state of ΔFosB protein has recently been shown to contribute to its unique stability relative to the transiently expressed full-length FosB (see Discussion)6,42, regulation of the fosB gene and splicing of its primary transcript have not to date been investigated as additional mechanisms possibly underlying the selective accumulation ΔFosB protein after chronic stimulation. The fosB gene consists of four exons (Figure 1A)9,33,43. Exons I, II, and III are included in both the final fosB and ΔfosB mRNA’s. Exon IV, in contrast, has a unique structure. Embedded in exon IV is an intron that is expressed in the final full-length fosB mRNA. This phenomenon of an intron found in the open reading frame of an mRNA which codes for protein is rare and is known as intron retention5. Although this intron, termed Intron IV, within Exon IV of the fosB gene is only 140 nucleotides long, it contains all of the motifs found in much larger constitutively excised introns: a 5’ splice site, a branch point, a polypyrimidine tract, and a 3’ splice site. For clarity’s sake, the exon sequences found upstream and downstream of Intron IV are labeled Exons IVa and IVb, respectively. ΔfosB mRNA is generated by the excision of the 140 nucleotide Intron IV. This splice event results in a one nucleotide frameshift in which a stop codon (TGA) is generated, leading to the premature truncation of the protein.

Figure 1. In vitro expression of fosB isoforms.

A. Alternative splicing of fosB RNA. ΔfosB is generated by a 140 nucleotide excision of “intronic” sequence found in the open reading frame of full length fosB. This splice event results in a one nucleotide frameshift which creates a stop codon (TGA). B. Expression of FosB and ΔFosB protein as detected by Western blotting. Quiescent PC12 cells were stimulated for 0–8 hours with 20% serum. The Mr of both proteins increases over time, which suggests the occurrence of post-translational modifications. The ΔFosB standard lane is from protein extracts of PC12 cells transiently transfected with a plasmid driving ΔFosB expression. Results shown are representative of 4 separate replications. C. Induction of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA by PMA and forskolin. Though induction levels vary (left graph), both stimuli induce the isoforms in very similar ratios (right graph). Data, expressed as mean ± sem (n=3 independent experiments each run in triplicate), were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). ANOVA results were as follows. Forskolin: ΔfosB, F(4,10)=13.4, p<0.01; fosB, F(4,10)=14.1, p<0.01; ratio, F(4,10)=15.2, p<0.01. PMA: ΔfosB, F(4,10)=421, p<0.01; fosB, F(4,10)=15.7, p<0.01; ratio, F(4,10)=34.6, p<0.01.

The goal of the present work was to determine whether fosB splicing is under dynamic regulation, and whether changes in this splicing mechanism contribute to the selective accumulation of ΔFosB after chronic stimulation.

2. Results

Induction of Endogenous fosB Isoforms In Vitro.

As a first step to understand the possible regulation of fosB splicing, we studied the induction of fosB and ΔfosB in cultured PC12 cells in response to a variety of stimuli. Figure 1B is a representative Western blot of a time course of serum stimulation of PC12 cells. After 18 hours of serum starvation, cells were treated with 20% serum and harvested 0 to 8 hours later. The blot was generated using an N-terminal anti-FosB antibody that recognizes both FosB and ΔFosB. ΔFosB is initially induced as a 33 kD protein, whose mass increases to 35–37 kD over several hours. These latter bands co-migrate with protein extracts from ΔFosB overexpressed in PC12 cells and with ΔFosB induced in brain by chronic stimulation (not shownsee 42). FosB (45–48 kD), which is partially obscured by a non-specific band, is also induced by serum stimulation. Like ΔFosB, FosB increases in apparent molecular mass, however, in contrast to ΔFosB, FosB begins to degrade by the 8 hour time point. In a similar fashion to serum, PMA (a phorbol ester which activates protein kinase C), forskolin (which activates adenylyl cyclase), and nicotine (which activates nicotinic cholinergic receptors on PC12 cells) also induced expression of FosB and ΔFosB with similar temporal patterns (not shown). These findings replicate the more persistent expression of ΔFosB in vitro established in previous studies8.

Using qPCR, PMA (100 nM) and forskolin (10 μM) induction of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA transcripts was measured in PC12 cells (Figure 1C). We chose these concentrations of the drugs, because in preliminary experiments they were shown to result in maximal effects. The left hand graph shows that both mRNA’s are induced rapidly and peak at ~1 hour of stimulation. After 8 hours, fosB and ΔfosB mRNA return to near baseline levels. The right hand graph depicts the relative ratio of fosB to ΔfosB mRNA. This ratio is 12:1 under basal conditions, but shifts to 2:1 at 2 hours of drug treatment and rebounds to near control levels by 8 hours. With decreasing magnitude, serum, PMA, forskolin, and nicotine treatments each induce fosB and ΔfosB mRNA’s. However, while the magnitude of induction varies for each of these treatments, the temporal pattern of the relative ratios of fosB:ΔfosB do not differ. These results suggest that expression levels of the two fosB isoforms are linked and that none of the tested stimuli can selectively induce one transcript relative to the other.

Induction of fosB Isoforms In Vivo

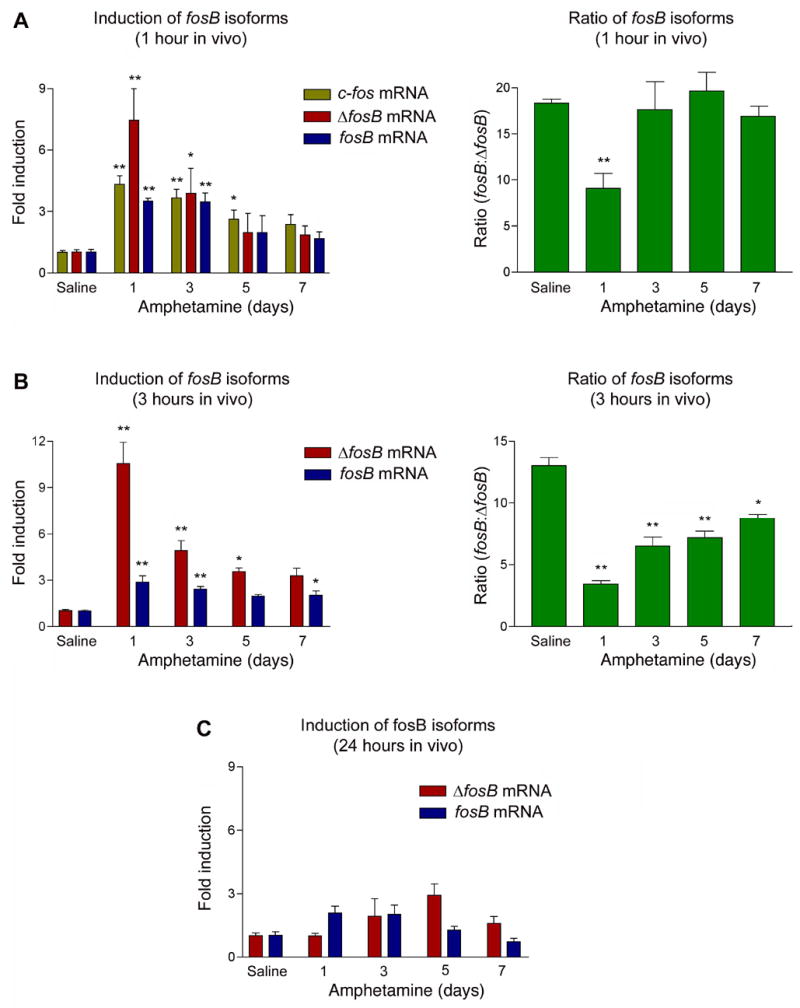

To measure the relative expression of fos and ΔfosB mRNA in vivo, male Sprague-Dawley rats were treated once daily with amphetamine (4 mg/kg) over a period of 1–7 days. Chronic amphetamine has been shown to selectively induce ΔFosB protein in striatum35. Animals were analyzed 1, 3, or 24 hours after the last injection. RNA was harvested from the striatum and quantified by qPCR. At the 1 hour time point, c-fos mRNA is rapidly induced by the first amphetamine treatment, with the induction gradually decreasing over the course of chronic treatment (Figure 2A, left panel). Similar to c-fos, both fosB and ΔfosB mRNA’s are robustly induced after acute administration of amphetamine, with the degree of induction decreasing with chronic dosing. Interestingly, the relative ratio of fosB to ΔfosB mRNA (which on average is 16:1 in saline controls) decreases most dramatically (to roughly 8:1) after the initial amphetamine dose (Figure 2A, right panel). A similar pattern of acute induction and partial desensitization is seen at the 3 hour time point (Figure 2B). Accordingly, the greatest change in the ratio of fosB to ΔfosB mRNA at 3 hours occurs after the first amphetamine exposure, with the ratio gradually returning toward normal levels with chronic treatment. Nevertheless, the ratio remains significantly different from baseline even after 7 amphetamine doses. By 24 hours after amphetamine, fosB and ΔfosB mRNA’s return to control levels under both acute and chronic treatment conditions (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. In vivo expression of fosB isoforms by acute and chronic amphetamine.

Sprague-Dawley rats were treated once daily with amphetamine (4 mg/kg) over a period of 1–7 days. Animals were sacrificed 1, 3, or 24 hours (A, B, C, respectively) after the last injection. The left hand panels depict induction of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA relative to its saline control. The right hand panels depict the relative ratio of fosB to ΔfosB mRNA. Note the largest shift in this ratio occurs with the first amphetamine exposure, when mRNA induction is greatest. Data, expressed as mean ± sem (n=4–6 animals/group), were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). ANOVA results were as follows. A: c-fos, F(4,16)=8.76, p<0.01; ΔfosB, F(4,19)=10.8, p<0.01; fosB, F(4,19)=8.86, p<0.01; ratio, F(4,18)=27.6, p<0.01. B: ΔfosB, F(4,18)=23.8, p<0.01; fosB, F(4,18)=7.01, p<0.01; ratio, F(4,18)=45.2, p<0.01. C: ΔfosB, F(4,17)=1.73, p=0.21; fosB, F(4,17)=4.81, p<0.01.

A very similar pattern of induction of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA was seen after stress, which is also known to selectively induce ΔFosB protein in striatum after chronic exposure39. As shown in Figure 3, both mRNA’s are induced in response to acute restraint stress, and this induction partially desensitizes after repeated stress exposures (Figure 3A and B, left panels). As with amphetamine, the greatest shift in fosB to ΔfosB mRNA ratios occurs after the initial stress exposure, with this ratio gradually returning toward normal after repeated stress (Figure 3A and B, right panels).

Figure 3. In vivo expression of fosB isoforms by acute and chronic stress.

A. Sprague-Dawley rats were treated with restraint stress and analyzed 15 min to 4 hours later. B. Rats were treated daily with restraint stress for 1 to 9 days and analyzed 1 hour after the last stress. The left hand panels depict induction of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA relative to its non-stressed control. The right hand panels depict the relative ratio of fosB to ΔfosB mRNA. As with amphetamine, the largest shift in this ratio occurs with the first stress exposure, when mRNA induction is greatest. Data, expressed as mean ± sem (n=4 animals/group), were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). ANOVA results were as follows. A: ΔfosB, F(5,22)=12.4, p<0.01; fosB, F(5,22)=12.6, p<0.01; ratio, F(5,22)=51.2, p<0.01. B: ΔfosB, F(4,18)=7.79, p<0.01; fosB, F(4,18)=7.24, p<0.01; ratio, F(4,18)=15.8, p<0.01.

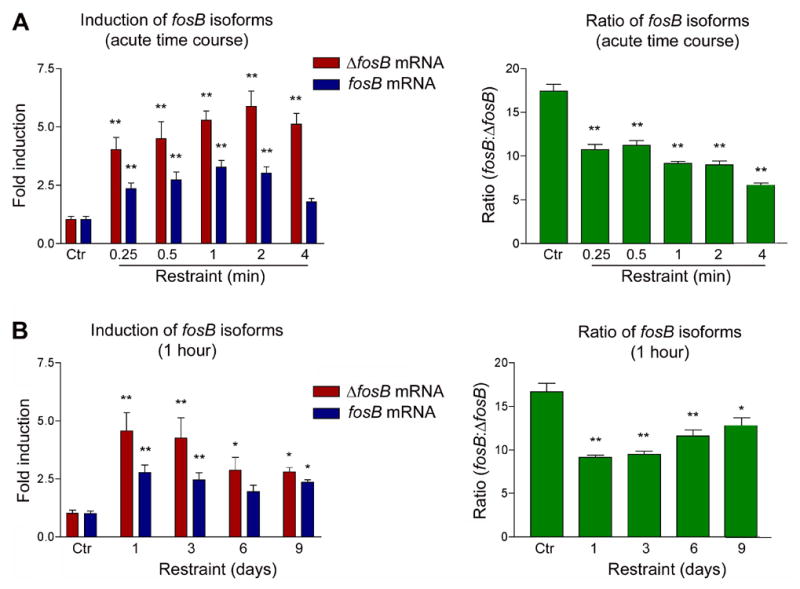

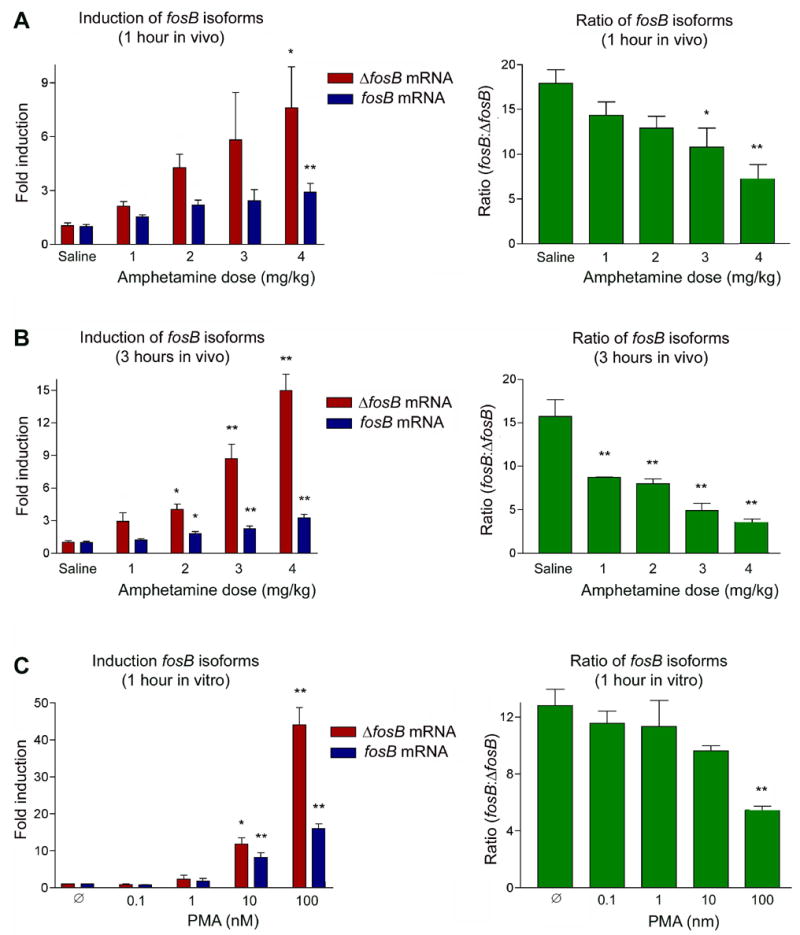

All of the above in vitro and in vivo experiments indicate that ΔfosB mRNA is preferentially spliced relative to fosB mRNA to the greatest extent after acute in vivo exposures (Figures 2 and 3) or initial in vitro stimulations (Figure 1), conditions associated with the greatest induction of the two transcripts. This outcome suggests that the generation of ΔfosB mRNA may be directly proportional to the stimulus applied to the system and, accordingly, to the degree of induction of the fosB gene. To test this hypothesis, animals were acutely administered increasing doses of amphetamine (1–4 mg/kg) and sacrificed 1 hour (Figure 4A) or 3 hours (Figure 4B) later. As seen in Figure 4 (left panels), fosB mRNA levels are induced to roughly equivalent levels regardless of dose, with relatively small increases in induction seen with increasing drug doses. In contrast, ΔfosB levels increase much more dramatically as the drug dose increases. As a result, the ratio of fosB to ΔfosB mRNA levels decreases with increasing doses of amphetamine (right panels).

Figure 4. Time course of induction of fosB mRNA isoforms after acute vs chronic amphetamine treatment.

Animals were administered saline or 4 mg/kg of amphetamine acutely (A) or chronically (7 days) (B) and sacrificed 0–12 hours later. Graphs depict induction of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA relative to its saline control. The two mRNA’s show similar time courses of induction, both acutely and chronically. Data are expressed as mean ± sem (n=4 animals/group). C. Determination of in vitro half lives of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA. Quiescient PC12 cells were stimulated with 20% serum for 1 hour and then treated with actinomycin D (green arrow). As seen in vivo, fosB and ΔfosB mRNA’s exhibit similar half lives. Data, expressed as mean ± sem (n=3 independent experiments each run in triplicate), were analyzed by ANOVA, the results of which were as follows. A: ΔfosB, F(5,22)=18.6, p<0.01, fosB, F(5,22)=19.3, p<0.01. B: ΔfosB, F(4,18)=11.0, p<0.01; fosB, F(4,18)=3.35, p<0.05. C: ΔfosB, F(7,24)=159, p<0.01; fosB, F(7,24)=493, p<0.01.

Similar results were obtained in vitro. Treatment of quiescent PC12 cells with increasing amounts of PMA (Figure 4C) leads to progressive increases in the induction of both fosB mRNA isoforms, with a decrease in the ratio of fosB to ΔfosB mRNA levels occurring only at the higher doses of PMA. The results are consistent with the hypothesis that the fosB to ΔfosB mRNA ratio, both in vivo and in vitro, is directly proportional to the strength of the inducing stimulus and the total level of induction of fosB transcripts.

Estimation of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA Half-Lives In Vivo and In Vitro

To obtain a rough estimate of the half-life of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA’s in vivo, animals received acute (1 dose) or chronic (7 doses) amphetamine (4 mg/kg) and were analyzed over a 12 hour period. In response to acute amphetamine, fosB mRNA levels reach maximal induction at 1 hour, whereas ΔfosB mRNA levels reach a peak at 3 hours, compared to saline-treated controls (Figure 5A). Both transcripts degrade to control levels by 12 hours. In animals injected chronically with amphetamine, induction of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA’s showed a very similar time course of accumulation and degradation as seen for acutely treated animals, albeit at reduced levels of induction (Figure 5B). These findings confirm that the selective accumulation of ΔFosB protein after chronic amphetamine administration is not associated with its sustained induction at the mRNA level7.

Figure 5. Dose response analysis of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA expression.

Animals were administered a single injection of amphetamine, at varying doses, and analyzed 1 (A) or 3 (B) hours later. The left hand panels depict induction of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA relative to its saline control. The right hand panels depict the relative ratio of fosB to ΔfosB mRNA. ΔfosB mRNA levels increase as drug dose increases to a much greater extent than seen for fosB mRNA. Data are expressed as mean ± sem (n=4 animals/group). C. PC12 cells were treated with increasing doses of PMA and harvested 1 hour after stimulation. The left hand panel depicts induction of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA relative to vehicle control. The right hand panel depicts the relative ratio of fosB to ΔfosB mRNA. The shift in this ratio was most significant at the highest induction levels, which was generated at the peak dose of PMA. Data, expressed as mean ± sem (n=3 independent experiments each run in triplicate), were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). ANOVA results were as follows. A: ΔfosB, F(4,20)=3.75, p<0.05; fosB, F(4,19)=3.81, p<0.05; ratio, F(4,18)=5.49, p<0.01. B: ΔfosB, F(4,18)=32.1, p<0.01; fosB, F(4,19)=16.5, p<0.01; ratio, F(4,18)=26.3, p<0.01. C: ΔfosB, F(4,15)=66.1, p<0.01; fosB, F(4,15)=53.5, p<0.01; ratio, F(4,14)=6.48, p=0.01.

To determine a more accurate half-life of the fosB isoforms, quiescent PC12 cells (serum starved for 18 hours) were exposed to 20% serum. After 1 hour of stimulation, the cells were treated with 5 μM actinomycin D, conditions known to inhibit new RNA transcription, and harvested 0–8 hours later. Figure 5C shows that fosB and ΔfosB mRNA’s (graphed relative to their respective controls) degrade at approximately the same rate.

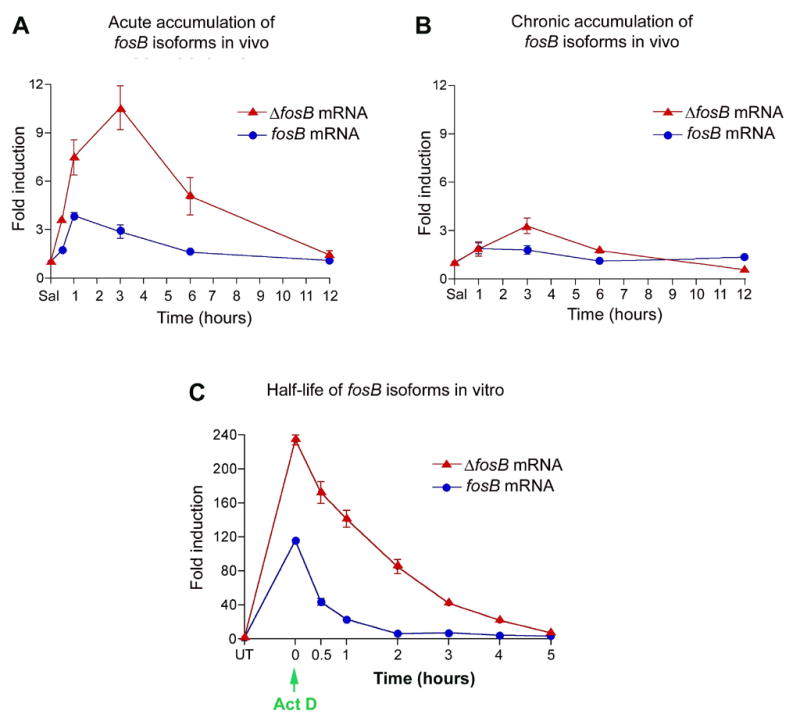

Role of PTB1 in fosB Expression

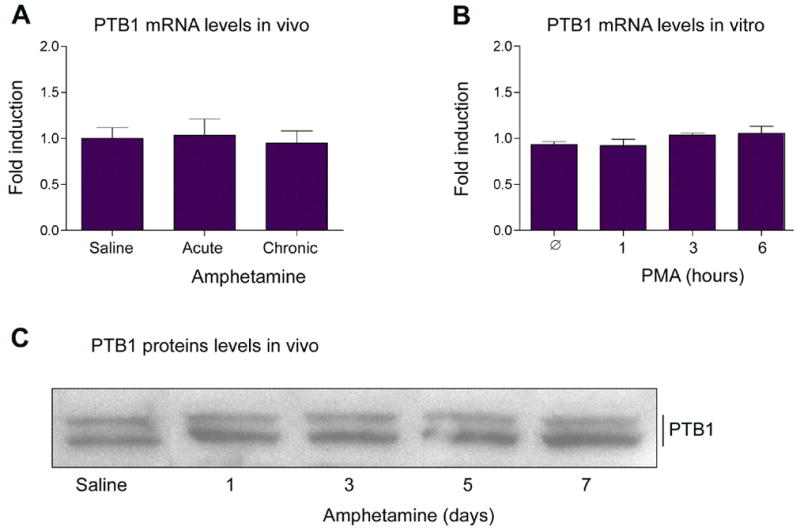

Lou et al.23 first demonstrated that PTB1 competes against the U2AF splicing complex to bind polypyrimidine rich regions in introns, and thereby negatively regulates splicing of nearby exons. Intron IV of the fosB primary transcript contains a PTB1 consensus binding site, and a recent study reported the ability of PTB1 to bind fosB pre-mRNA25. These findings make PTB1 an attractive candidate to regulate the splicing of the fosB transcript. We were interested in the possibility of whether total levels of PTB1 might be altered (i.e., decreased) in brain in association with the accumulation of ΔFosB protein. Animals received daily injections of amphetamine (4 mg/kg) for 1 to 7 days and were analyzed 1 hour after their last injection. First, we found that striatum (including nucleus accumbens) contains high levels of PTB1 mRNA and protein (Figure 6). However, we found that PTB1 mRNA and protein levels were unaffected by either acute or chronic amphetamine administration (Figure 6A,C). PTB1 expression was also not altered in cultured PC12 cells treated with PMA (Figure 6B). These data show that PTB1 mRNA and protein levels remain constant while fosB and ΔfosB mRNA levels fluctuate.

Figure 6. Lack of regulation of PTB1 expression.

PTB1 mRNA levels were measured after in vivo amphetamine administration (A) and in vitro PMA treatment of PC12 cells (B). In A, Acute=1 hour after a single amphetamine injection; Chronic=1 hour after the last of 7 daily doses of amphetamine. C. Rats received daily injections of amphetamine (4 mg/kg) for 1 to 7 days and were analyzed 1 hour after the last injection. Striatal extracts were then Western blotted with an anti-PTB1 antibody. RNA and protein remain unchanged over the course of amphetamine or PMA treatment. Data, expressed as mean ± sem (n=4 animals/group [A] or 3 independent experiments each run in triplicate [B]), were analyzed by ANOVA, the results of which were as follows. A: F(2,9)=0.102, p=0.91. B: F(3,12)=0.791, p=0.53.

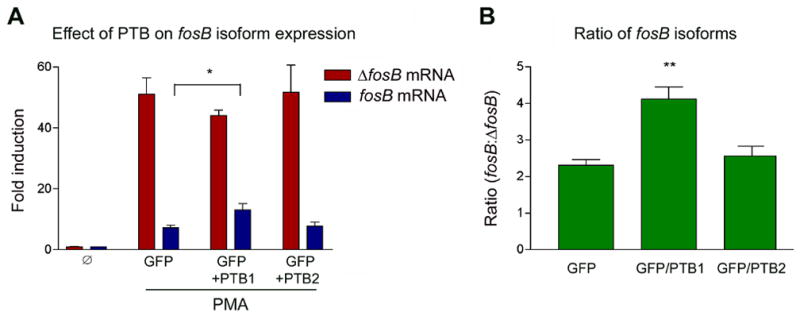

To determine if PTB1 protein could alter the ratio of fosB to ΔfosB mRNA levels, PC12 cells were transfected with a GFP plasmid plus an empty plasmid, a plasmid encoding human PTB1 or a plasmid encoding human PTB2. PTB2, also called neuronal PTB, is expressed in brain and peripheral tissues and shares high sequence similarity (84% at the amino acid level) to PTB126. PTB2 binds polypyrimidine regions and acts as a repressor (although weaker than PTB1) of splicing in vitro3. Quantification by qPCR indicates that PTB1 and PTB2 mRNA’s are present at roughly equivalent levels in PC12 cells as well as in striatal tissue (data not shown). After transfection, cells were serum starved for 18 hours and then stimulated with 20% serum. Relative to the empty vector, cells overexpressing PTB1 showed increased induction of fosB mRNA and a concomitant decrease in ΔfosB mRNA (Figure 7, left panel). The result is a 2-fold increase in the ratio of fosB to ΔfosB mRNA upon PTB1 overexpression (right panel). In contrast, overexpression of PTB2 had no effect on the induction fosB or ΔfosB mRNA’s or on the ratio of the two isoforms. Overexpression of yet another homolog of PTB1, hnRNPA1, also had no effect fosB induction (not shown). A similar result was seen when cells were stimulated with 100 nM PMA (not shown).

Figure 7. Effect of PTB1 overexpression on fosB and ΔfosB induction.

PC12 cells were transfected with GFP or GFP plus human PTB1 or PTB2 and simultaneously serum starved for 22 hours. Cells were then stimulated with 20% serum for 2 hours. Transfection efficiency was approximately 40%. Although the effect on mRNA levels was not dramatic (left panel), analysis of fosB to ΔfosB mRNA ratios (right panel) showed a two-fold increase in the relative induction of fosB mRNA in the presence of excess PTB1 protein. Expression of PTB2 was without effect. Data, expressed as mean ± sem (3 independent experiments each run in triplicate), were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test (*p<0.05, **p<0.01). ANOVA results were as follows. A: ΔfosB, F(3,12)=30.7, p<0.01; fosB, F(3,12)=28.8, p<0.01. B: ratio, F(2.9)=15.2, p<0.01.

3. Discussion

The results of the present study show that the accumulation of ΔFosB protein in brain after chronic stimulation is not associated with progressive increases in the splicing of fosB primary transcript into ΔfosB mRNA. Rather, the greatest shift in the generation of ΔfosB mRNA versus fosB mRNA occurs during initial induction of the fosB gene, a phenomenon observed both in vitro and in vivo. Our hypothesis is that the splicing of the fosB primary transcript is regulated primarily by the quantity of the transcript available to the splicing machinery. That is, above a certain threshold level, the remaining primary transcript is alternatively spliced into ΔfosB. This splicing phenomenon may be regulated by PTB1. We propose that, under basal conditions, PTB1 or related proteins binds the large majority of the fosB primary transcript, and thereby inhibits the generation of ΔfosB mRNA. Only when PTB1 is saturated with transcript does the ratio of fosB to ΔfosB decrease significantly, because the unbound primary transcript is spliced into ΔfosB.

Thus, we show in the present manuscript that the largest shift in fosB to ΔfosB mRNA ratios occurs under the several experimental conditions when the total level of fosB gene expression is highest. Such conditions include initial amphetamine or stress exposures, since the degree of fosB gene induction partially desensitizes with repeated exposure to these stimuli. These conditions of maximal gene induction also include the highest dose of amphetamine, compared to lower drug doses, or the highest concentration of PMA in vitro, compared to lower concentrations. Our data also demonstrate that the time course of ΔfosB mRNA induction and degradation is very similar to that of fosB mRNA: in vivo, ΔfosB mRNA peaks only slightly later than fosB mRNA and, both in vivo and in vitro, shows a slightly longer half-life. The molecular basis for the slightly delayed induction of ΔfosB mRNA is unknown, but could conceivably be due to the requirement for splicing in its generation. By 12 hours, both mRNA’s are back to control levels, and there is no evidence that ΔfosB mRNA accumulates with chronic stimulation. This corroborates earlier work which also showed the lack of sustained induction of ΔfosB mRNA after chronic administration of cocaine or electroconvulsive seizures7.

There are two major classes of RNA binding proteins that participate in pre-mRNA splicing: serine/arginine-rich (SR) proteins and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (hnRNP’s). SR proteins function predominantly in the splicing of constitutive exons through exon definition12. In contrast to SR proteins, which recruit and promote spliceosomal activity, hnRNP’s affect the processing of primary transcripts by negatively regulating alternative splicing10. In addition, hnRNP’s influence mRNA transcription, stabilization, transport to the cytoplasm, polyadenylation, and translation11. The hnRNP, PTB1, is an attractive candidate to regulate the production of fosB transcripts for several reasons. First, PTB1 was first described as a negative regulator of the U2AF splicing complex by competitively binding polypyrimidine tracts to which the splicing complex bound23. Second, Intron IV of fosB, which is flanked by Exons IVa and IVb, contains a consensus binding site for the PTB1 protein37. Third, preliminary studies have indicated that PTB1 binds to the fosB transcript in vitro, and that mutation of the PTB1 consensus site in the transcript obliterates this binding25.

Our findings provide further support for a role of PTB1 in regulating the alternative splicing of fosB transcripts. We show that striatum (including nucleus accumbens) contains high levels of PTB1 mRNA and protein. Overexpression of PTB1 in PC12 cells increases expression of fosB mRNA and decreases expression of ΔfosB mRNA without change in the total induction of the combined transcripts. A common criticism of overexpression studies in the splicing field is that hnRNP’s, which negatively regulate splicing, may act as partial dominant negatives by interacting with the spliceosome and thus causing an overall depression in splicing. To resolve this issue, we overexpressed two other snRNP’s, PTB2 and hnRNPA1. Both proteins act as negative regulators of splicing and are the two closest homologues in terms of sequence identity to PTB111. In fact, PTB1 and PTB2 are so similar in structure that it is predicted that PTB2 arose from a gene duplication event of PTB141. Importantly, we found that overexpression of either PTB2 or hnRNPA1 did not affect the induction of fosB or ΔfosB mRNA’s in PC12 cells. These data suggest that the influence of PTB1 on fosB regulation is specific and not due to a general depression in splicing. Further work is needed to more definitively establish a role for PTB1 in fosB splicing. For example, it would be important in future studies to selectively knockdown PTB1, e.g., with an RNAi mechanism, and show that this increases ΔfosB mRNA expression. Unfortunately, we were unable to achieve selective RNAi knockdown of PTB1, possibly because of its high sequence identity to other hnRNP’s as mentioned above. This work must, therefore, await future experiments.

Despite the evidence that PTB1 regulates fosB splicing, we found no evidence for its involvement in the ability of chronic stimuli to selectively induce ΔFosB protein. Thus, if PTB1 were involved in ΔFosB induction, then its levels would have to decrease during the course of chronic amphetamine exposure. In contrast to this hypothesis, PTB1 mRNA and protein levels were unaltered in striatum after acute or chronic amphetamine administration. PTB1 levels were likewise unaffected in vitro by PMA treatment. However, these observations do not rule out other potential changes in fosB splicing during the course of chronic stimulation. Note, for example, that the fosB:ΔfosB mRNA ratios in striatum, after either chronic amphetamine or chronic stress, do not fully return to baseline levels even after a week of exposures. This despite the fact that total levels of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA expressed at these later time points are relatively low compared to their initial induction, when our model would suggest that the splicing of fosB primary transcripts would be maximally suppressed by PTB1 or related machinery. Consequently, further work is needed to study whether other aspects of the fosB splicing complex might be altered under chronic treatment conditions. Nevertheless, we must emphasize that this persisting change in fosB to ΔfosB mRNA ratios is relatively small and probably does not contribute appreciably to the selective induction of ΔFosB protein, since fosB mRNA levels are roughly 10-fold higher than ΔfosB mRNA levels under these conditions.

Our data provide further support for the observation that the inducibility of fos family genes decreases with repeated stimulation. This “desensitization” has been reported for c-fos and fosB after several types of stimuli3,15-18,39,40. We show here partial desensitization of c-fos, fosB, and ΔfosB mRNA in response to chronic amphetamine or stress administration. Importantly, however, this desensitization is partial, which means that ΔfosB mRNA continues to be induced with chronic treatment. The mechanism responsible for the partial desensitization of fos family genes remains unknown. The c-fos and fosB promoters contain two major cis-acting elements that are thought to mediate their robust and rapid induction: a serum response element (SRE) and cAMP response element (CRE)see 14,32. In addition, the genes possess an AP-1 site, but this may exert a repressive feedback effect on the gene. Future studies will be needed to determine whether chronic treatments cause partial desensitization of gene induction by altering the structure of the c-fos or fosB genes (i.e., their chromatin architecture22) or, instead, altering the transcription factors or their upstream signaling pathways that regulate the transcription of these genes.

In summary, findings of the present study indicate that the selective accumulation of ΔFosB protein in brain after chronic stimulation does not involve the preferential generation of this protein via the selective generation of ΔfosB mRNA. Rather, these data, and other recent studies, suggest that the accumulation of ΔFosB is due primarily to the unique stability of the protein as compared to all other Fos family proteins. In a recent study, we found that the half-life of endogenously expressed ΔFosB protein in PC12 cells is greater than 48 hours, whereas full-length FosB protein exhibits a half-life of 1–2 hours. This dramatic difference in half-life appears to be mediated by two mechanisms. First, ΔFosB, due to its truncated C-terminus, lacks two degron domains present in full-length FosB, which target the protein to rapid degradation via proteasomal-dependent and independent pathways6. One of these degrons is highly conserved in all Fos family proteins and uniquely absent in ΔFosB. In addition, we showed recently that ΔFosB is phosphorylated on its N-terminus and that this phosphorylation further stabilizes ΔFosB, with no effect on full-length FosB42. Together, these data support a scheme that can explain the shifting pattern of FosB and ΔFosB protein expression shown here in Figure 1B. As FosB and ΔFosB proteins are expressed, both isoforms are phosphorylated, which explains their increasing apparent Mr on SDS gel electrophoresis. Concurrently, the native and phosphorylated isoforms of FosB are subjected to rapid degradation due to the C-terminal degrons in the protein and hence do not accumulate. In contrast, ΔFosB is spared rapid degradation, due to the absence of these degrons, which enables phosphorylated, stabilized isoforms of ΔFosB to persist in the cell and accumulate. In future experiments, it will be important to better establish the molecular mechanisms governing induction of the fosB gene and its splicing, which could offer novel ways to interfere with the accumulation of ΔFosB protein and its unique neural and behavioral plasticity.

4. Experimental Procedures

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Houston), 250–350 g, were used for all experiments. Rats were pair-housed in an AAALAC-approved colony and all experiments conformed to the NIH Guide for the use and care of laboratory animals and were approved by UT Southwestern’s institutional animal care and use committee. Rats were housed on a 12 hour light/dark cycle with lights on at 7:00 a.m. All procedures were conducted during the light phase of the cycle.

Amphetamine Treatment

Amphetamine hemi-sulfate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was administered at a dose of 4 mg/kg (ip; doses calculated from the salt) unless otherwise noted. For all experiments, animals received 10 daily injections of saline or amphetamine: “acute” amphetamine animals received 9 daily injections of saline, followed by an amphetamine injection on day 10, while “chronic” amphetamine animals received 3 injections of saline followed by 7 daily amphetamine injections. This dose and treatment regimen for amphetamine is based on previous studies35. Rats were killed by rapid decapitation, whole striatum was dissected and placed in RNA Stat-60 reagent (Tel-Test, Frienswood, TX). The tissue was briefly sonicated to homogeneity by a tabletop Ultrasonic Processor (Cole Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL) set at an amplitude of 40.

Restraint Stress

Rats were placed in a plastic conical sleeve (DecapiCone, Braintree; model DC200) for up to 60 min, after which time the animals were removed from the cone and placed back into their home cage for time points exceeding 60 min. Control rats were handled daily but not subjected to stress. This stress paradigm was employed, since it has been shown to robustly induce ΔFosB in striatum39.

Cell Culture and Transfection

PC12 cells (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% horse serum and 5% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) with antibiotics at 37°C and 95% O2-5% CO2. Cells were transiently transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Plasmids for human polypyrimidine tract binding proteins (PTB1 and PTB2) were a gift of Douglas Black (UCLA). Transfection efficiency was determined by co-expression of GFP with all plasmids. The total amount of DNA within experiments was kept constant by adding empty vector to the transfection mixture when necessary. The phorbol ester PMA (Sigma), and the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin (Sigma), were dissolved in DMSO. Actinomycin D (Sigma) was dissolved in ethanol.

RNA Isolation

RNA was harvested following the manufacturers protocol. Briefly, the organic layer was extracted with chloroform and precipitated with isopropanol in the presence of Linear Acrylamide (Ambion, Austin TX). The RNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and re-suspended in DEPC water. The purified total RNA was DNAse treated (Ambion) and reverse transcribed to cDNA with random hexamers using a first-strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen). The amount of cDNA synthesized from a target mRNA was quantified using real-time PCR (qPCR). The following primers were used to amplify specific cDNA regions of the transcripts of interest: ΔFosB (5’-AGGCAGAGCTGGAGTCGGAGAT-3’ and 5’-GCCGAGGACTTGAACTTCACTCG-3’), FosB (5’-GTGAGAGATTTGCCAGGGTC-3’ and 5’-AGAGAGAAGCCGTCAGGTTG-3’), c-Fos (5'-GGAATTAACCTGGTGCTGGA-3' and 5’-TGAACATGGACGCTGAAGAG-3'), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (5’-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3’ and 5’-TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA-3’), PTB1 (5’-AACGGTGGTGTGGTCAAAGG-3' and 5’-GTGGACTTGGAAAAGGACACTC-3'), and PTB2 (5’-CATCCCTCTTAGCTGTTCCAGG-3’ and 5’-GGGCGTAACCATCTCTTCATTTA-3’). qPCR was performed in triplicate using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System (95°C - 10 min, 1 cycle; 95°C - 20 sec, 61°C [except for c-Fos - 59°C], 30 sec, 72°C - 33 sec, 35 cycles; melt curve from 60°C – 95°C) with SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). GAPDH quantification was used as an internal control for normalization. Fold differences of mRNA levels over control values were calculated using the ΔΔCt method as described in the Applied Biosystems manual.

Protein Isolation

Striatum was isolated from amphetamine- and saline-treated rats by gross dissection from 1 mm-thick coronal sections. Brain samples were sonicated to homogeneity in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES, 0.4 M NaCl, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1% (v/v) NP-40, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, and 5 μl/ml of a protease inhibitor mixture. Protein concentration was determined by the DC protein assay method (Bio-Rad) using bovine serum albumin as a standard19.

Western Blot

Equal amounts of protein (50 μg) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10% polyacrylamide gels), and transferred to PVDF membranes (0.2 μm) (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked for 60 min in TBST (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% [v/v] TWEEN-20) containing 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk and immunoblotted using a 1:1,000 dilution of a polyclonal rabbit FosB antibody (generated by Biosource, International, Camarillo, CA) or a polyclonal rabbit N-terminal PTB1 antibody (gift of Douglas Black). A monoclonal mouse GAPDH antibody (Pierce, Rockford, IL) was used at a dilution of 1:10,000 to verify equal loading and transfer. After washing 4 times for 20 min in TBST, antibody binding was revealed by incubation with a 1:10,000 dilution of goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-linked IgG (Pierce) and the SuperSignal West Dura immunoblotting detection system (Pierce). A 1:20,000 dilution of rabbit anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-linked IgG (Pierce) was used to identify GAPDH. Chemiluminescence was detected by autoradiography using Kodak autoradiography film.

Statistical analyses

All data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVAs) tests followed by Dunnett’s or Bonferroni’s post-hoc tests, and all statistical tests were corrected for multiple comparisons. Statistical data are shown in the figure legends.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jonathan Hommel for his insight and technical assistance and Michael Donovan for his critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from NIDA and NIMH.

Abbreviations

- PTB

polypyrimidine tract binding protein

- AP-1

activator protein-1

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- PC12 cells

rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Andersson M, Westin JE, Cenci MA. Time course of striatal DeltaFosB-like immunoreactivity and prodynorphin mRNA levels after discontinuation of chronic dopaminomimetic treatment. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:661–666. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashiya M, Grabowski PJ. A neuron-specific splicing switch mediated by an array of pre-mRNA repressor sites: evidence of a regulatory role for the polypyrimidine tract binding protein and a brain-specific PTB counterpart. RNA. 1997;3(9):996–1015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkins J, Carlezon WA, Chlan J, Nye HE, Nestler EJ. Region-specific induction of ΔFosB by repeated administration of typical versus atypical antipsychotic drugs. Synapse. 1999;33(118–128) doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199908)33:2<118::AID-SYN2>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bing G, Wang W, Qi Q, Feng Z, Hudson P, Jin L, Zhang W, Bing R, Hong JS. Long-term expression of Fos-related antigen and transient expression of delta FosB associated with seizures in the rat hippocampus and striatum. J Neurochem. 1997;68:272–279. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68010272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black DL. Mechanisms of alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:291–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carle TL, et al. Absence of Conserved C-Terminal Degron Domain Contributes to ΔFosB's Unique Stability. Eur J Neurosci. 2005 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, et al. Regulation of delta FosB and FosB-like proteins by electroconvulsive seizure and cocaine treatments. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48(5):880–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen J, et al. Chronic Fos-related antigens: stable variants of deltaFosB induced in brain by chronic treatments. J Neurosci. 1997;17(13):4933–41. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-04933.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dobrazanski P, Noguchi T, Kovary K, Rizzo CA, Lazo PS, Bravo R. Both products of the fosB gene, FosB and its short form, FosB/SF, are transcriptional activators in fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5470–5478. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dreyfuss G, et al. hnRNP proteins and the biogenesis of mRNA. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:289–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreyfuss G, V, Kim N, Kataoka N. Messenger-RNA-binding proteins and the messages they carry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3(3):195–205. doi: 10.1038/nrm760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graveley BR. Sorting out the complexity of SR protein functions. RNA. 2000;6(9):1197–211. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graybiel AM, Moratalla R, Robertson HA. Amphetamine and cocaine induce drug-specific activation of the c-fos gene in striosome-matrix compartments and limbic subdivisions of the striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(17):6912–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herdegen T, Leah JD. Inducible and constitutive transcription factors in the mammalian nervous system: control of gene expression by Jun, Fos and Krox, and CREB/ATF proteins. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1998;28(3):370–490. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiroi N, Graybiel AM. Atypical and typical neuroleptic treatments induce distinct programs of transcription factor expression in the striatum. J Comp Neurol. 1996;374:70–83. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961007)374:1<70::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiroi N, et al. FosB mutant mice: loss of chronic cocaine induction of Fos-related proteins and heightened sensitivity to cocaine's psychomotor and rewarding effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(19):10397–402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiroi N, Brown J, Ye H, Saudou F, Vaidya VA, Duman RS, Greenberg ME, Nestler EJ. Essential role of the fosB gene in molecular, cellular, and behavioral actions of electroconvulsive seizures. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6952–6962. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06952.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hope B, et al. Regulation of immediate early gene expression and AP-1 binding in the rat nucleus accumbens by chronic cocaine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(13):5764–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hope BT, et al. Chronic electroconvulsive seizure (ECS) treatment results in expression of a long-lasting AP-1 complex in brain with altered composition and characteristics. J Neurosci. 1994;14(7):4318–28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04318.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hope BT, et al. Induction of a long-lasting AP-1 complex composed of altered Fos-like proteins in brain by chronic cocaine and other chronic treatments. Neuron. 1994;13(5):1235–44. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelz MB, et al. Expression of the transcription factor deltaFosB in the brain controls sensitivity to cocaine. Nature. 1999;401(6750):272–6. doi: 10.1038/45790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar A, Choi KH, Renthal W, Tsankova NM, Theobald DEH, Truong HT, Russo SJ, LaPlant Q, Sasaki TS, Whistler KN, Neve RL, Self DW, Nestler EJ. Chromatin remodeling is a key mechanism underlying cocaine-induced plasticity in striatum. Neuron. 2005;48:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lou H, et al. Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein positively regulates inclusion of an alternative 3'-terminal exon. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(1):78–85. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandelzys A, Gruda MA, Bravo R, Morgan JI. Absence of a persistently elevated 37 kDa fos-related antigen and AP-1- like DNA-binding activity in the brains of kainic acid-treated fosB null mice. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5407–5415. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05407.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marinescu V, Ehamann S, Potashkin J. PTB interacts with splicing regulatory elements of FosB. Soc Neurosci Abs. 2005:226.4. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markovtsov V, et al. Cooperative assembly of an hnRNP complex induced by a tissue-specific homolog of polypyrimidine tract binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(20):7463–79. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7463-7479.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romanelli MG, Lorenzi P, Morandi C. Organization of the human gene encoding heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein type I (hnRNP I) and characterization of hnRNP I related pseudogene. Gene. 2000;255:267–272. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00331-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lillevali K, Kulla A, Ord T. Comparative expression analysis of the genes encoding polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB) and its neural homologue (brPTB) in prenatal and postnatal mouse brain. Mech Dev. 2001;101:217–230. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McClung CA, Nestler EJ. Regulation of gene expression and cocaine reward by CREB and DeltaFosB. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1208–1215. doi: 10.1038/nn1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McClung CA, et al. DeltaFosB: a molecular switch for long-term adaptation in the brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;132(2):146–54. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moratalla R, Elibol B, Vallejo M, Graybiel AM. Network-level changes in expression of inducible Fos-Jun proteins in the striatum during chronic cocaine treatment and withdrawal. Neuron. 1996;17:147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan JI, Curran T. Immediate-early genes: ten years on. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:66–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakabeppu Y, Nathans D. A naturally occurring truncated form of FosB that inhibits Fos/Jun transcriptional activity. Cell. 1991;64:751–759. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90504-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nestler EJ, Barrot M, Self DW. ΔFosB: A molecular switch for addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11042–11046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191352698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nye HE, et al. Pharmacological studies of the regulation of chronic FOS-related antigen induction by cocaine in the striatum and nucleus accumbens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275(3):1671–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nye HE, Nestler EJ. Induction of chronic Fras (Fos-related antigens) in rat brain by chronic morphine administration. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:636–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oberstrass FC, et al. Structure of PTB bound to RNA: specific binding and implications for splicing regulation. Science. 2005;309(5743):2054–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1114066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peakman MC, Colby C, Perrotti LI, Tekumalla P, Carle T, Ulery P, Chao J, Duman C, Steffen C, Monteggia L, Allen MR, Stock JL, Duman RS, McNeish JD, Barrot M, Self DW, Nestler EJ, Schaeffer E. Inducible, brain region-specific expression of a dominant negative mutant of c-Jun in transgenic mice decreases sensitivity to cocaine. Brain Res. 2003;970:73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perrotti LI, et al. Induction of deltaFosB in reward-related brain structures after chronic stress. J Neurosci. 2004;24(47):10594–602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2542-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Persico AM, Schindler CW, O’Hara BF, Brannock MT, Uhl GR. Brain transcription factor expression: effects of acute and chronic amphetamine and injection stress. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1993;20:91–100. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Polydorides AD, et al. A brain-enriched polypyrimidine tract-binding protein antagonizes the ability of Nova to regulate neuron-specific alternative splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(12):6350–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110128397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ulery PG, Rudenko G, Nestler EJ. Regulation of DeltaFosB stability by phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2006;26(19):5131–42. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yen J, Wisdom RM, Tratner I, Verma IM. An alternative spliced form of FosB is a negative regulator of transcriptional activation and transformation by Fos proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5077–5081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young ST, Porrino LJ, Iadarola MJ. Cocaine induces striatal c-fos-immunoreactive proteins via dopaminergic D1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(4):1291–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zachariou V, Bolanos CA, Selley DE, Theobald D, Cassidy MP, Kelz MB, Shaw-Lutchmann T, Berton O, Sim-Selley LJ, DiLeone RJ, Kumar A, Nestler EJ. ΔFosB: An essential role for ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens in morphine action. Nature Neurosci. 2006;9:205–211. doi: 10.1038/nn1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]