Abstract

A common single-nucleotide polymorphism in the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene, a methionine (Met) substitution for valine (Val) at codon 66 (Val66Met), is associated with alterations in brain anatomy and memory, but its relevance to clinical disorders is unclear. We generated a variant BDNF mouse (BDNFMet/Met) that reproduces the phenotypic hallmarks in humans with the variant allele. BDNFMet was expressed in brain at normal levels, but its secretion from neurons was defective. When placed in stressful settings, BDNFMet/Met mice exhibited increased anxiety-related behaviors that were not normalized by the antidepressant, fluoxetine. A variant BDNF may thus play a key role in genetic predispositions to anxiety and depressive disorders.

Depression and anxiety disorders have genetic predispositions, yet the particular genes that contribute to this pathology are not known. One candidate gene is BDNF, because of its established roles in neuronal survival, differentiation, and synaptic plasticity. The recent discovery of a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the bdnf gene (Val66Met), found only in humans, leading to a Met substitution for Val at codon 66 in the prodomain, has provided a valuable tool to assess potential contributions of BDNF to affective disorders. This polymorphism is common in human populations with an allele frequency of 20 to 30% in Caucasian populations (1). This alteration in a neurotrophin gene correlates with reproducible alterations in human carriers. Humans heterozygous for the Met allele have smaller hippocampal volumes (2–4) and perform poorly on hippocampal-dependent memory tasks (5, 6). However, in genetic association studies for depression and anxiety disorders, there is little consensus as to whether this allele confers susceptibility.

The mechanisms that contribute to altered BDNFMet function have been studied in neuronal culture systems. The distribution of BDNFMet to neuronal dendrites and its activity-dependent secretion are decreased (6–8). These trafficking abnormalities are likely to reflect impaired binding of BDNFMet to a sorting protein, sortilin, which interacts with BDNF in the prodomain region that encompasses the Met substitution (7). However, fundamental questions remain as to how these in vitro effects relate to the in vivo consequences of this SNP in humans.

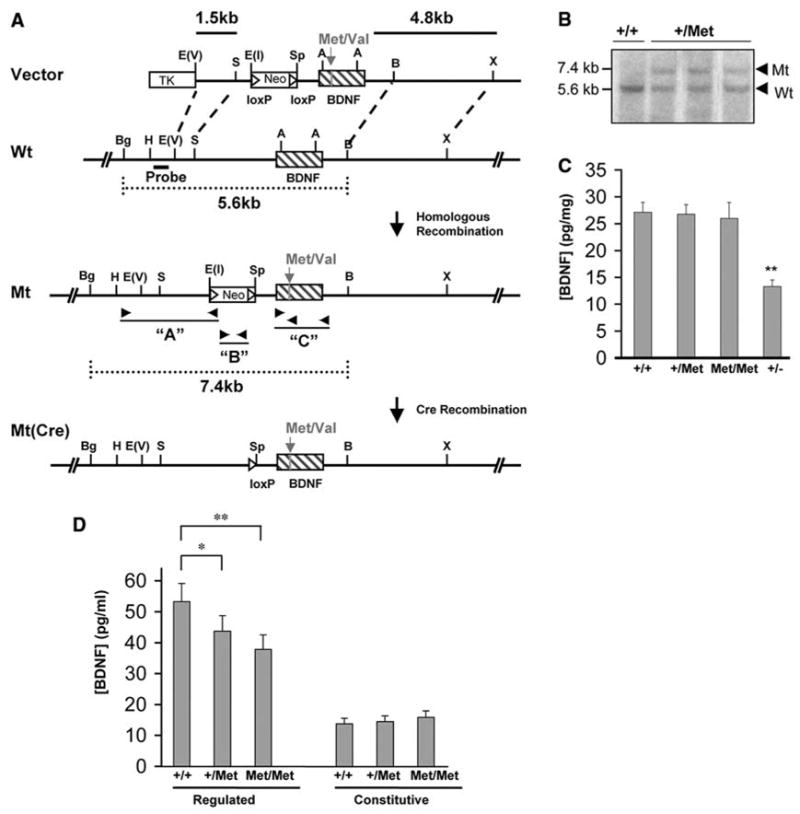

To generate a transgenic mouse in which BDNFMet is endogenously expressed, we designed a BDNFMet knock-in allele in which transcription of BDNFMet is regulated by endogenous BDNF promoters (Fig. 1, A and B). Heterozygous BDNF+/Met mice were intercrossed to yield BDNF+/+, BDNF+/Met, and BDNFMet/Met offspring at Mendelian rates. Brain lysates from BDNF+/Met and BDNFMet/Met mice showed comparable levels of BDNF as that of wild-type (WT) controls (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Generation and validation of BDNFMet transgenic mice. (A) Schematic diagram of the strategy used to replace the coding region of the BDNF gene with BDNFMet. The entire coding region is in exon V. For the variant BDNF, a point mutation has been made (G196A) to change the valine in position 66 to a methionine. (B) Southern blots of representative embryonic stem cell clones for BDNFMet. Bgl II and Bam HI restriction enzyme digestion and 5′ external probe indicated in (A) were used to detect homologous replacement in the BDNF locus. The 5.6-kilobase (kb) WT and 7.4-kb rearranged variant DNA bands are indicated. (C) BDNF ELISA analyses of total BDNF levels from postnatal day 21 (P21) brain lysates from WT (+/+), heterozygous (+/Met), and homozygous (Met/Met) mice, as well as BDNF heterozygous KO mice (+/−) (**P < 0.01, Student’s t test). (D) Hippocampal-cortical neurons obtained from embryonic day 18 (E18) BDNF+/Met (+/Met), BDNFMet/Met (Met/Met), and WT (+/+) pups were cultured. After 72 hours, media were collected under depolarization (regulated) or basal (constitutive) secretion conditions as described previously (10). Media were then concentrated and analyzed by BDNF ELISA. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Student’s t test).

To assess whether there were global or selective defects in BDNFMet secretion, hippocampal-cortical neurons were obtained from BDNFMet/Met, BDNF+/Met, and WT embryos. Secretion studies were performed, and BDNF in the resultant media was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). There was no difference in constitutive secretion from either BDNF+/Met or BDNFMet/Met neurons (Fig. 1C). We observed a significant decrease in regulated secretion from both BDNF+/Met (18 ± 2% decrease, P < 0.01) and BDNFMet/Met (29 ± 3% decrease, P < 0.01) neurons (Fig. 1C). As the majority of BDNF is released from the regulated secretory pathway in neurons (9), impaired regulated secretion (29 ± 3%) from BDNFMet/Met neurons represents a significant decrease in available BDNF.

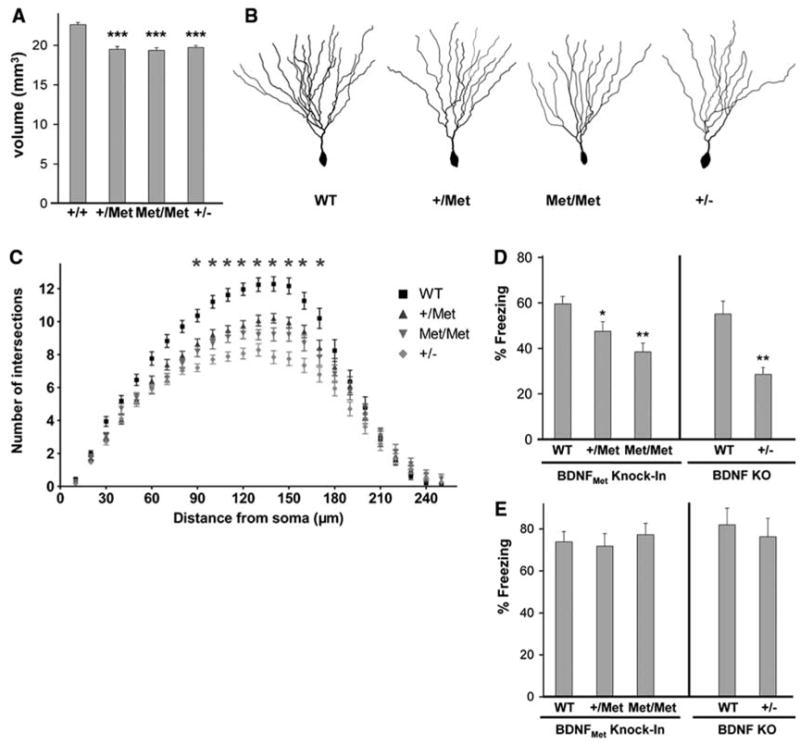

We first assessed an alteration associated with the Met allele in humans: decreased hippocampal volume (3, 4, 10). BDNFMet mice were histologically prepared for stereologic hippocampal volume estimation from Nissl-stained sections. Using Cavalieri volume estimation, we detected a significant decrease in hippocampal volume of 13.7 ± 0.7% and 14.4 ± 0.7% for BDNF+/Met or BDNFMet/Met mice, respectively, as compared with WT mice (Fig. 2A). This volume decrease was also comparable to the 13.8 ± 0.6% decrease in the heterozygous BDNF knock-out (BDNF+/−) mice (Fig. 2A). We also measured striatal volume, because in human studies this structure has not been reported to be altered by the BDNFMet polymorphism (2, 3), and we found no alteration in mouse striatal volumes across genotype (fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Altered hippocampal anatomy and behavior in transgenic BDNFMet mice. (A) Total hippocampal volume estimations were obtained from Nissl-stained sections of adult (P60) hippocampi from WT (+/+), heterozygous (+/Met), homozygous (Met/Met), and heterozygous BDNF KO (+/−) mice by Cavalieri analyses. All results are presented as means ± SEM determined from analysis of six mice per genotype (***P < 0.001, Student’s t test). (B) Examples of Golgi-stained dentate gyrus neurons from P60 WT (+/+), heterozygous (+/Met), homozygous (Met/Met), and heterozygous BDNF KO (+/−) mice. (C) Sholl analyses of dentate gyrus neurons from P60 mice, five mice per genotype, 10 neurons per mouse. All results are presented as means ± SEM determined from analysis of five mice per genotype and statistics in comparison with WT controls (*P < 0.001). Fear-conditioned learning in adult transgenic BDNFMet mice. WT (+/+), heterozygous (+/Met), homozygous (Met/Met), and heterozygous BDNF (+/−) KO mice were tested in (D) contextual and (E) cue-dependent fear conditioning. The percentage of time spent freezing in each session was quantified. All results are presented as means ± SEM determined from analysis of eight mice per genotype (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Student’s t test).

Because secreted BDNF regulates neuronal differentiation, the decreased volume in BDNFMet mice may be accounted for by altered neuronal morphology. We used Golgi staining to visualize individual dentate gyrus neurons. At 8 weeks of age, there was no difference in cell soma area between BDNF+/Met and BDNFMet/Met mice and their WT controls (fig. S2). Next, we analyzed dendritic complexity in these same neurons (Fig. 2B). Sholl analysis revealed a decrease in dendritic arbor complexity at 90 μM and greater distances from the soma in BDNF+/Met and BDNFMet/Met mice (Fig. 2C). We also used fractal dimension analysis to quantify how completely a neuron fills its dendritic field (11). There was a significant decrease in dendritic complexity in dentate gyrus neurons from BDNF+/Met and BDNFMet/Met mice (fig. S3).

In humans, the other major alteration associated with the BDNFMet allele is impairment in hippocampus-dependent memory. We performed a test that selectively assesses hippocampus- and amygdala-dependent learning: fear conditioning. BDNF+/Met and BDNFMet/Met mice showed significantly less context-dependent memory than WT mice (Fig. 2D). In contrast, there was no difference in cue-dependent fear conditioning (Fig. 2E). Of note, prior studies of BDNF+/− mice also showed a deficit in contextual fear learning and no alteration in cue-dependent learning (12). The degree of memory impairment was related to the number of alleles of BDNFMet (Fig. 2D). BDNFMet/Met mice displayed other behavioral abnormalities similar to BDNF+/− mice (15), such as intermale aggressiveness (fig. S4). BDNFMet/Met mice also displayed elevated body weight, which was first evident at 2 months of age, similar to BDNF+/− mice (15) (fig. S5). Although other BDNF knockout (KO) mice with >50% decrease in BDNF levels previously exhibited increased locomotor activity (13, 14), BDNF+/−(15), BDNF+/Met, and BDNFMet/Met mice (figs. S6 and S7B) had no significant alterations in locomotor activity, which suggests a potential BDNF dose-related effect on activity.

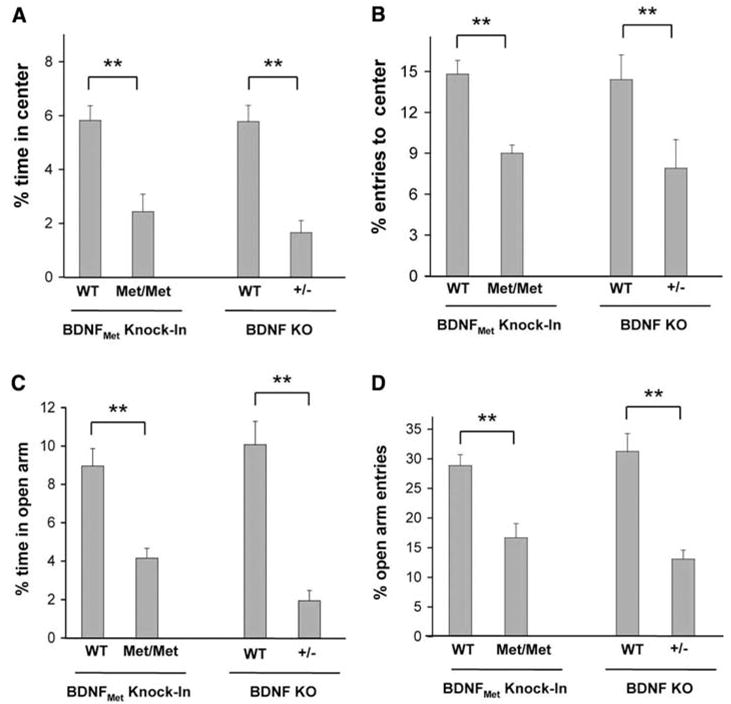

BDNF has also been shown to regulate stress and anxiety-related behaviors. Acute or chronic stress leads to decreased BDNF expression in the hippocampus, with subsequent enhancement of anxiety-related behaviors (16). In addition, conditional BDNF KO mice exhibit enhanced avoidance of aversive settings (13). In this context, we focused on adult BDNFMet mice and performed two standard measures of anxiety-like behavior that place subjects in conflict situations. In comparison with littermate WT control mice, BDNFMet/Met mice had decreased exploratory behavior as demonstrated by a reduction in the percentage of time spent in the center compartment (Fig. 3A) and the number of entries into the center compartment (Fig. 3B) in the open-field test. BDNFMet/Met mice also exhibited, in the elevated plus maze test, a significant decrease in the percentage of time spent in open arms (Fig. 3C) and a significant reduction in the percentage of entries into open arms (Fig. 3D). In both tests, there were no significant differences in total distance traveled or the number of entries into enclosed arms between groups (fig. S7, A and B). In both of these tests, heterozygous BDNF+/Met mice did not display increases in anxiety-related behaviors (fig. S8). BDNF+/−mice also displayed increased anxiety-related behaviors in these two tests, similar in effect size to BDNFMet/Met mice (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Anxiety-related behavior in BDNFMet/Met mice in the open field (A and B) and elevated plus maze (C and D). Percentage of time spent in the center (A) and entries into the center (B) in the open field are shown, as well as percentage time spent in the open arm (C) and percentage of open arm entries (D) in the plus maze. All results are presented as means ± SEM determined from analysis of eight mice per genotype (**P < 0.01).

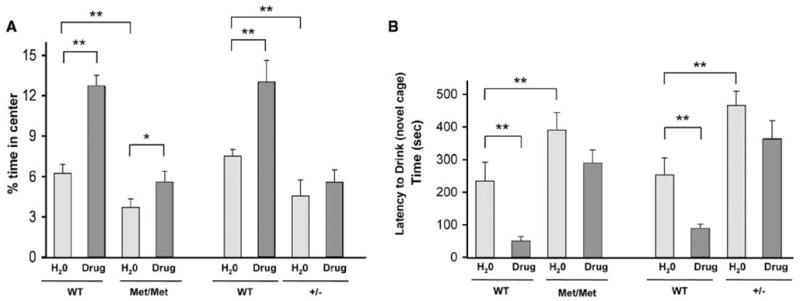

A common treatment for anxiety in humans are serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), for which one postulated mechanism of action involves increasing BDNF levels (17). In rodents, this class of drugs increases hippocampal BDNF levels in a time frame corresponding to the onset of SSRI action (18) and is effective in decreasing anxiety-related behaviors in rodent models of mood disorders (19). BDNFMet/Met mice were treated orally with fluoxetine (18 mg/kg of body weight per day) or vehicle for 21 days before assessment in two tests: open field and novelty-induced hypophagia. This dosing regimen was based on prior studies showing that this dose led to a therapeutic serum levels (19). In the open-field test, fluoxetine led to a significant increase in time spent in the center for WT mice (Fig. 4A), as well as to an increase in entries into the center (fig. S9), which indicated its effectiveness in decreasing anxiety-related behaviors. However, there was a blunted response to fluoxetine in BDNFMet/Met mice, with respect to time spent in the center (Fig. 4A), as well as entries into the center (fig. S9). Furthermore, the reduction in exploration could not be explained by changes in locomotor activity (fig. S7A).

Fig. 4.

Decreased response to long-term fluoxetine in BDNFMet/Met mice in the (A) open-field and (B) novelty-induced hypophagia tests. In the open-field test, percentage of time spent in the center in the absence (H2O) or presence of fluoxetine (drug) treatment was measured. In the novelty-induced hypophagia test, latency to begin drinking in a novel cage in the absence (H2O) or presence of fluoxetine (drug) treatment is shown in seconds. All results are presented as means ± SEM determined from analysis of eight mice per genotype (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

We used a specific behavioral paradigm for anxiety-related behavior, novelty-induced hypophagia, which has been suggested to be a more sensitive test of SSRI response (20, 21). In this conflict test, mice are trained to approach a reward (sweetened milk) in their home cage and then placed in a novel brightly lit cage. The latency to approach and drink the sweetened milk is a measure of the anxiety-related behavior associated with this task (20). BDNFMet/Met mice treated with vehicle had a significantly greater latency to drink in the novel cage as compared with WT controls (Fig. 4B). Treatment with long-term fluoxetine did not significantly decrease the latency to drink in BDNFMet/Met mice, as in WT littermate mice treated in parallel with long-term fluoxetine (Fig. 4B). In both of these assays, BDNF+/−mice displayed similar diminished response to fluoxetine as compared with their WT controls (Fig. 4, A and B).

These results provide an example of a human SNP that has been modeled in transgenic mice that reproduce the same phenotypic hallmarks observed in Caucasian populations. Our subsequent analyses of these mice elucidated a phenotype that had not been established in human carriers: increased anxiety. When placed in conflict settings, BDNFMet/Met mice display increased anxiety-related behaviors in three separate tests and thus provide a genetic link between BDNF and anxiety. Genetic association studies have found that the Met allele has been associated with increased trait anxiety (22), but other studies have not replicated these findings (23–25). Two main differences in our study design led to discerning this anxiety-related phenotype. First, mice were subjected to conflict tests to elicit the increased anxiety-related behavior, whereas human studies relied on questionnaires. Second, the anxiety-related phenotype was only present in mice homozygous for the Met allele, which suggested that association studies that focused primarily on humans heterozygous for the Met allele may not detect an association. In this context, another human genetic polymorphism in the serotonin transporter (5HTLPR) was associated with depression only in homozygote subjects with past trauma histories (26), which suggested that environmental influences, as well as gene dosage, were required for this SNP to influence psychiatric pathology.

The form of anxiety elicited in these BDNFMet/Met mice was not responsive to a common SSRI. It has previously been shown in conditional BDNF KO mice that there is altered expression or function of serotonin receptors (27–29). These results suggest that humans with this allele may not have optimal responses to this class of antidepressants. Currently, there are no reliable genetic or nongenetic biomarkers to predict who will respond to an SSRI. The transgenic BDNFMet/Met mouse may serve as a valuable model to identify novel pharmacologic approaches to treating anxiety disorders.

Finally, the BDNFMet/Met mouse represents a unique model that directly links activity-dependent release of BDNF to a defined set of in vivo consequences. In these mice, BDNFMet expression is equivalent to that of BDNF expression in WT controls (Fig. 1C), but there is an ~30% deficit in activity-dependent release of BDNFMet from neurons (Fig. 1D), that contributes to a specific set of anatomical and behavioral deficits. Because BDNFMet/Met mice are similar to BDNF+/− mice in that they have BDNF levels that are lower by 50%, it is possible that there is a threshold level of lowered BDNF that is crossed by both mutant mice. It also remains possible that there are additional defects in BDNFMet processing that may contribute to the observed deficits, although in vitro studies in neurons suggest no defect in BDNFMet processing (6, 8). In all, these findings indicate a new direction in therapeutic strategies to rescue anxiety symptoms in humans with this polymorphic allele. Drug discovery strategies to increase BDNF release from synapses or to prolong the half life of secreted BDNF may improve therapeutic responses for humans with this common BDNF polymorphism.

Supplementary Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/314/5796/140/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S9

References and Notes

References and Notes

- 1.Shimizu E, Hashimoto K, Iyo M. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004;126B:122. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bueller JA, et al. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:812. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pezawas L, et al. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2680-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szeszko PR, et al. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:631. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hariri AR, et al. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6690. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06690.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egan MF, et al. Cell. 2003;112:257. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen ZY, et al. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6156. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1017-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen ZY, et al. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0348-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu B. Neuron. 2003;39:735. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00538-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bueller JA, et al. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:812. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caserta F, et al. J Neurosci Methods. 1995;56:133. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)00115-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu IY, Lyons WE, Mamounas LA, Thompson RF. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7958. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1948-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rios M, et al. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1748. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.10.0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monteggia LM, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402141101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyons WE, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McEwen BS. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;933:265. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duman RS, Heninger GR, Nestler EJ. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:597. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830190015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nibuya M, Morinobu S, Duman RS. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7539. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-11-07539.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dulawa SC, Holick KA, Gundersen B, Hen R. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1321. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dulawa SC, Hen R. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:771. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santarelli L, et al. Science. 2003;301:805. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang X, et al. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1353. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lang UE, et al. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2005;180:95. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sen S, et al. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:397. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Surtees PG, et al. J Psychiatr Res. 2006 25 July; doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.05.015. published online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caspi A, et al. Science. 2003;301:386. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan JP, Unger TJ, Byrnes J, Rios M. Neuroscience. 2006 13 July; doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.002. published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rios M, et al. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:408. doi: 10.1002/neu.20233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hensler JG, Ladenheim EE, Lyons WE. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1139. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Supported by the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (F.S.L., Z.-Y.C., D.G.H.); DeWitt-Wallace Fund of the New York Community Trust (F.S.L., D.G.H.); Nancy Pritzker Depression Network (F.S.L., D.G.H.); Sackler Institute (F.S.L.); Foundation for the author of National Excellent Doctoral Dissertation of People’s Republic of China (No. 200229) (Z.-Y.C.); Shanghai Rising-Star Program (05QMH1401) (Z.-Y.C.); Taishan Scholar Program (Z.-Y.C.); National Key Basic Research Program 2006CB503800 (Z.-Y.C.); and NIH(NS052819 to F.S.L., MH068850 to F.S.L., NS30687 to B.L.H., and MH060478 to K.G.B.). We thank M. Chao, L. Tessarollo, F. Maxfield, C. Dreyfus, C. Glatt, P. Perez, and K. Teng for helpful discussions.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/314/5796/140/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S9

References and Notes