Abstract

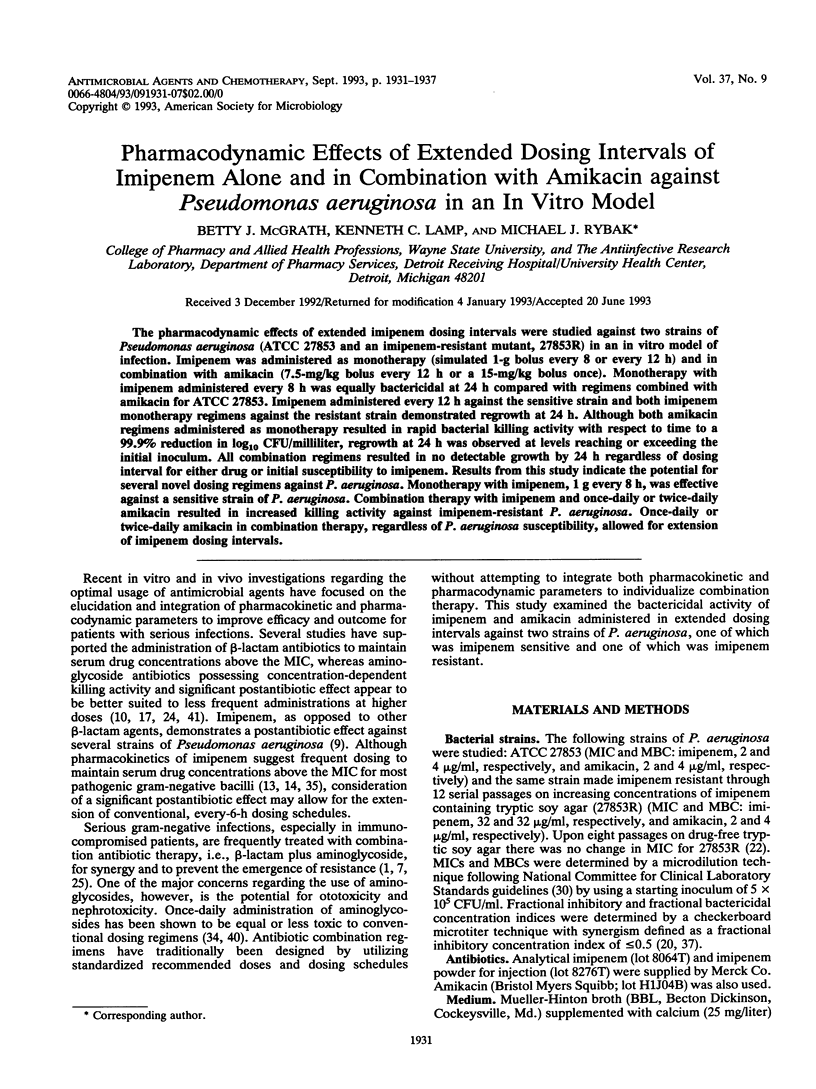

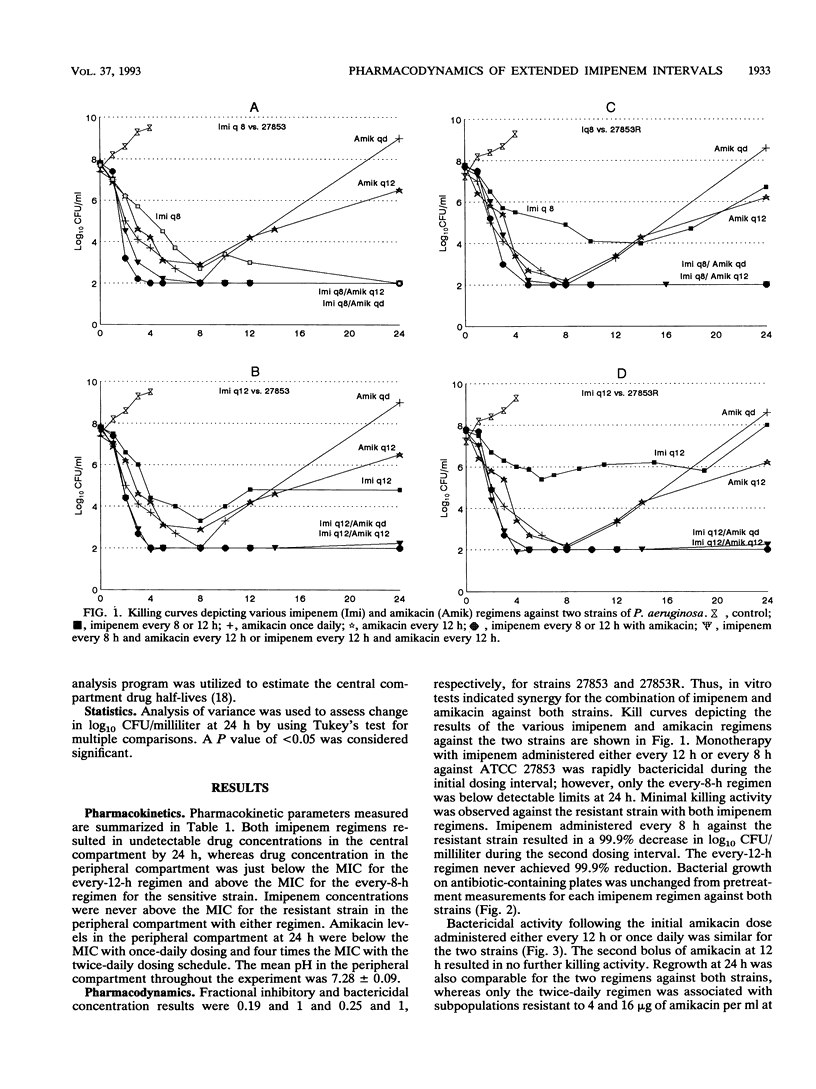

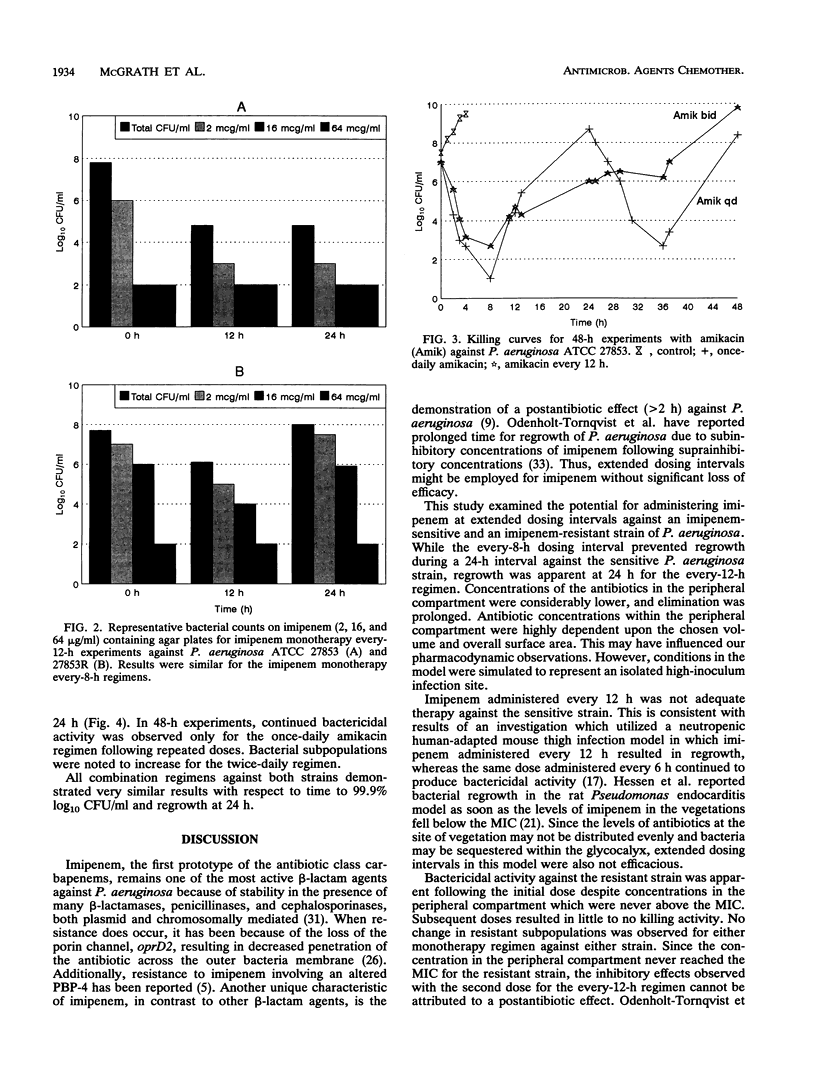

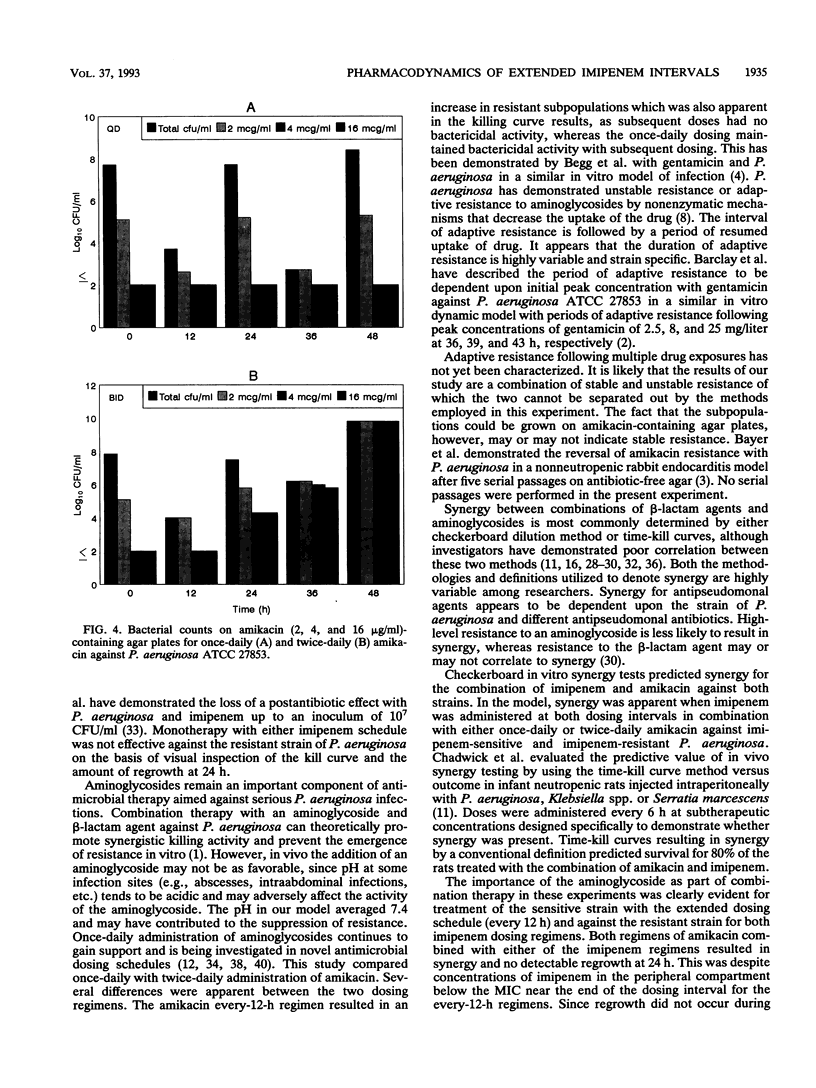

The pharmacodynamic effects of extended imipenem dosing intervals were studied against two strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853 and an imipenem-resistant mutant, 27853R) in an in vitro model of infection. Imipenem was administered as monotherapy (simulated 1-g bolus every 8 or every 12 h) and in combination with amikacin (7.5-mg/kg bolus every 12 h or a 15-mg/kg bolus once). Monotherapy with imipenem administered every 8 h was equally bactericidal at 24 h compared with regimens combined with amikacin for ATCC 27853. Imipenem administered every 12 h against the sensitive strain and both imipenem monotherapy regimens against the resistant strain demonstrated regrowth at 24 h. Although both amikacin regimens administered as monotherapy resulted in rapid bacterial killing activity with respect to time to a 99.9% reduction in log10 CFU/milliliter, regrowth at 24 h was observed at levels reaching or exceeding the initial inoculum. All combination regimens resulted in no detectable growth by 24 h regardless of dosing interval for either drug or initial susceptibility to imipenem. Results from this study indicate the potential for several novel dosing regimens against P. aeruginosa. Monotherapy with imipenem, 1 g every 8 h, was effective against a sensitive strain of P. aeruginosa. Combination therapy with imipenem and once-daily or twice-daily amikacin resulted in increased killing activity against imipenem-resistant P. aeruginosa. Once-daily or twice-daily amikacin in combination therapy, regardless of P. aeruginosa susceptibility, allowed for extension of imipenem dosing intervals.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Allan J. D., Moellering R. C., Jr Management of infections caused by gram-negative bacilli: the role of antimicrobial combinations. Rev Infect Dis. 1985 Nov-Dec;7 (Suppl 4):S559–S571. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.supplement_4.s559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay M. L., Begg E. J., Chambers S. T. Adaptive resistance following single doses of gentamicin in a dynamic in vitro model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992 Sep;36(9):1951–1957. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.9.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer A. S., Norman D., Kim K. S. Efficacy of amikacin and ceftazidime in experimental aortic valve endocarditis due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985 Dec;28(6):781–785. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.6.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg E. J., Peddie B. A., Chambers S. T., Boswell D. R. Comparison of gentamicin dosing regimens using an in-vitro model. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1992 Apr;29(4):427–433. doi: 10.1093/jac/29.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellido F., Veuthey C., Blaser J., Bauernfeind A., Pechère J. C. Novel resistance to imipenem associated with an altered PBP-4 in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990 Jan;25(1):57–68. doi: 10.1093/jac/25.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaser J. In-vitro model for simultaneous simulation of the serum kinetics of two drugs with different half-lives. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985 Jan;15 (Suppl A):125–130. doi: 10.1093/jac/15.suppl_a.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodey G. P., Bolivar R., Fainstein V., Jadeja L. Infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Rev Infect Dis. 1983 Mar-Apr;5(2):279–313. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan L. E., Van Den Elzen H. M. Effects of membrane-energy mutations and cations on streptomycin and gentamicin accumulation by bacteria: a model for entry of streptomycin and gentamicin in susceptible and resistant bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977 Aug;12(2):163–177. doi: 10.1128/aac.12.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante C. I., Drusano G. L., Tatem B. A., Standiford H. C. Postantibiotic effect of imipenem on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984 Nov;26(5):678–682. doi: 10.1128/aac.26.5.678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci G., Biordi L., Vicentini C., Bologna M. Determination of imipenem in human plasma, urine and tissue by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1990;8(3):283–286. doi: 10.1016/0731-7085(90)80038-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick E. G., Shulman S. T., Yogev R. Correlation of antibiotic synergy in vitro and in vivo: use of an animal model of neutropenic gram-negative sepsis. J Infect Dis. 1986 Oct;154(4):670–675. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig W. A., Redington J., Ebert S. C. Pharmacodynamics of amikacin in vitro and in mouse thigh and lung infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991 May;27 (Suppl 100):29–40. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.suppl_c.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drusano G. L., Plaisance K. I., Forrest A., Bustamante C., Devlin A., Standiford H. C., Wade J. C. Steady-state pharmacokinetics of imipenem in febrile neutropenic cancer patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987 Sep;31(9):1420–1422. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.9.1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drusano G. L., Standiford H. C. Pharmacokinetic profile of imipenem/cilastatin in normal volunteers. Am J Med. 1985 Jun 7;78(6A):47–53. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(85)90101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley M. N., Blaser J., Gilbert D., Mayer K. H., Zinner S. H. Combination therapy with ciprofloxacin plus azlocillin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: effect of simultaneous versus staggered administration in an in vitro model of infection. J Infect Dis. 1991 Sep;164(3):499–506. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliopoulos G. M., Moellering R. C., Jr Antibiotic synergism and antimicrobial combinations in clinical infections. Rev Infect Dis. 1982 Mar-Apr;4(2):282–293. doi: 10.1093/clinids/4.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flückiger U., Segessenmann C., Gerber A. U. Integration of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of imipenem in a human-adapted mouse model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991 Sep;35(9):1905–1910. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.9.1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GARROD L. P., WATERWORTH P. M. Methods of testing combined antibiotic bactericidal action and the significance of the results. J Clin Pathol. 1962 Jul;15:328–338. doi: 10.1136/jcp.15.4.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison M. W., Vance-Bryan K., Larson T. A., Toscano J. P., Rotschafer J. C. Assessment of effects of protein binding on daptomycin and vancomycin killing of Staphylococcus aureus by using an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990 Oct;34(10):1925–1931. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.10.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessen M. T., Pitsakis P. G., Levison M. E. Absence of a postantibiotic effect in experimental Pseudomonas endocarditis treated with imipenem, with or without gentamicin. J Infect Dis. 1988 Sep;158(3):542–548. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.3.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapotas N. M. Acclimatization resistance of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa prototype strain to imipenem. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1991 Sep;44(9):985–994. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapusnik J. E., Hackbarth C. J., Chambers H. F., Carpenter T., Sande M. A. Single, large, daily dosing versus intermittent dosing of tobramycin for treating experimental pseudomonas pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 1988 Jul;158(1):7–12. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klastersky J., Zinner S. H. Synergistic combinations of antibiotics in gram-negative bacillary infections. Rev Infect Dis. 1982 Mar-Apr;4(2):294–301. doi: 10.1093/clinids/4.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korvick J. A., Yu V. L. Antimicrobial agent therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991 Nov;35(11):2167–2172. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.11.2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M. J., Drusano G. L., Mobley H. L. Emergence of resistance to imipenem in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987 Dec;31(12):1892–1896. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.12.1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moellering R. C., Jr Antimicrobial synergism--an elusive concept. J Infect Dis. 1979 Oct;140(4):639–641. doi: 10.1093/infdis/140.4.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moellering R. C., Jr, Eliopoulos G. M., Allan J. D. Beta-lactam/aminoglycoside combinations: interactions and their mechanisms. Am J Med. 1986 May 30;80(5C):30–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu H. C., Labthavikul P. Comparative in vitro activity of N-formimidoyl thienamycin against gram-positive and gram-negative aerobic and anaerobic species and its beta-lactamase stability. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982 Jan;21(1):180–187. doi: 10.1128/aac.21.1.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norden C. W. Problems in determination of antibiotic synergism in vitro. Rev Infect Dis. 1982 Mar-Apr;4(2):276–281. doi: 10.1093/clinids/4.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenholt-Tornqvist I., Löwdin E., Cars O. Pharmacodynamic effects of subinhibitory concentrations of beta-lactam antibiotics in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991 Sep;35(9):1834–1839. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.9.1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell S. H., Thompson W. L., Luthe M. A., Stern R. C., Grossniklaus D. A., Bloxham D. D., Groden D. L., Jacobs M. R., DiScenna A. O., Cash H. A. Once-daily vs. continuous aminoglycoside dosing: efficacy and toxicity in animal and clinical studies of gentamicin, netilmicin, and tobramycin. J Infect Dis. 1983 May;147(5):918–932. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.5.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J. D., Meisinger M. A., Ferber F., Calandra G. B., Demetriades J. L., Bland J. A. Pharmacokinetics of imipenem and cilastatin in volunteers. Rev Infect Dis. 1985 Jul-Aug;7 (Suppl 3):S435–S446. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.supplement_3.s435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusnak M. G., Drake T. A., Hackbarth C. J., Sande M. A. Single versus combination antibiotic therapy for pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa in neutropenic guinea pigs. J Infect Dis. 1984 Jun;149(6):980–985. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.6.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabath L. D. Synergy of antibacterial substances by apparently known mechanisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (Bethesda) 1967;7:210–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulkens P. M. Efficacy and safety of aminoglycosides once-a-day: experimental and clinical data. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1990;74:249–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon P. L., Desrochers C. Stability of imipenem in Mueller-Hinton agar stored at 4 degrees C. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985 Nov;28(5):711–712. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.5.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verpooten G. A., Giuliano R. A., Verbist L., Eestermans G., De Broe M. E. Once-daily dosing decreases renal accumulation of gentamicin and netilmicin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1989 Jan;45(1):22–27. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1989.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelman B., Gudmundsson S., Leggett J., Turnidge J., Ebert S., Craig W. A. Correlation of antimicrobial pharmacokinetic parameters with therapeutic efficacy in an animal model. J Infect Dis. 1988 Oct;158(4):831–847. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.4.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]