Abstract

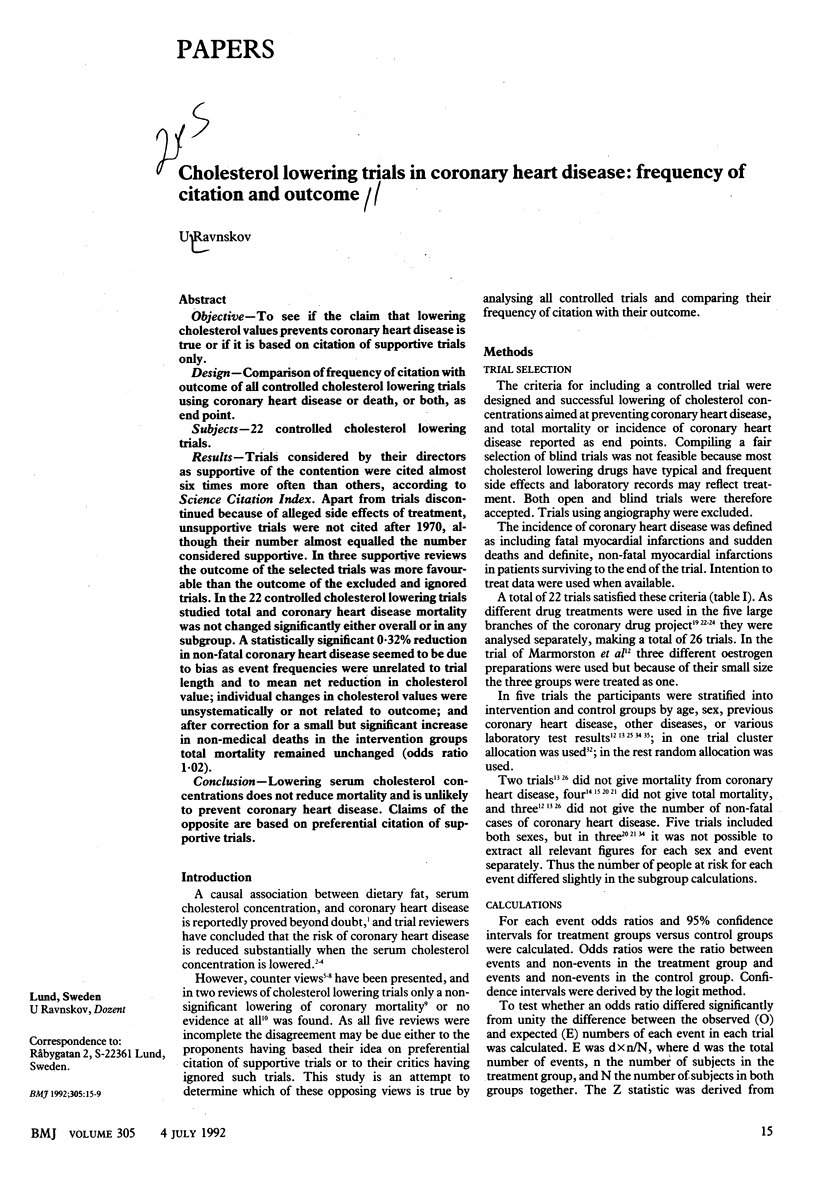

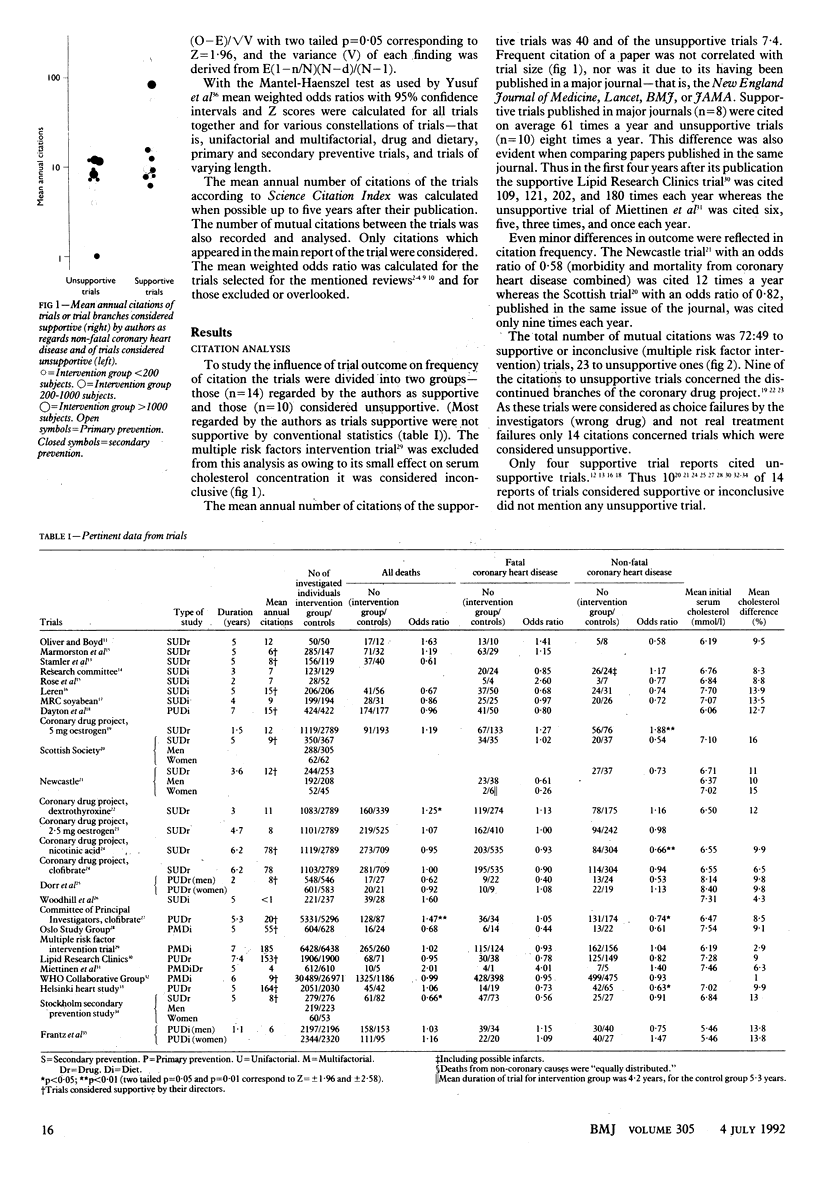

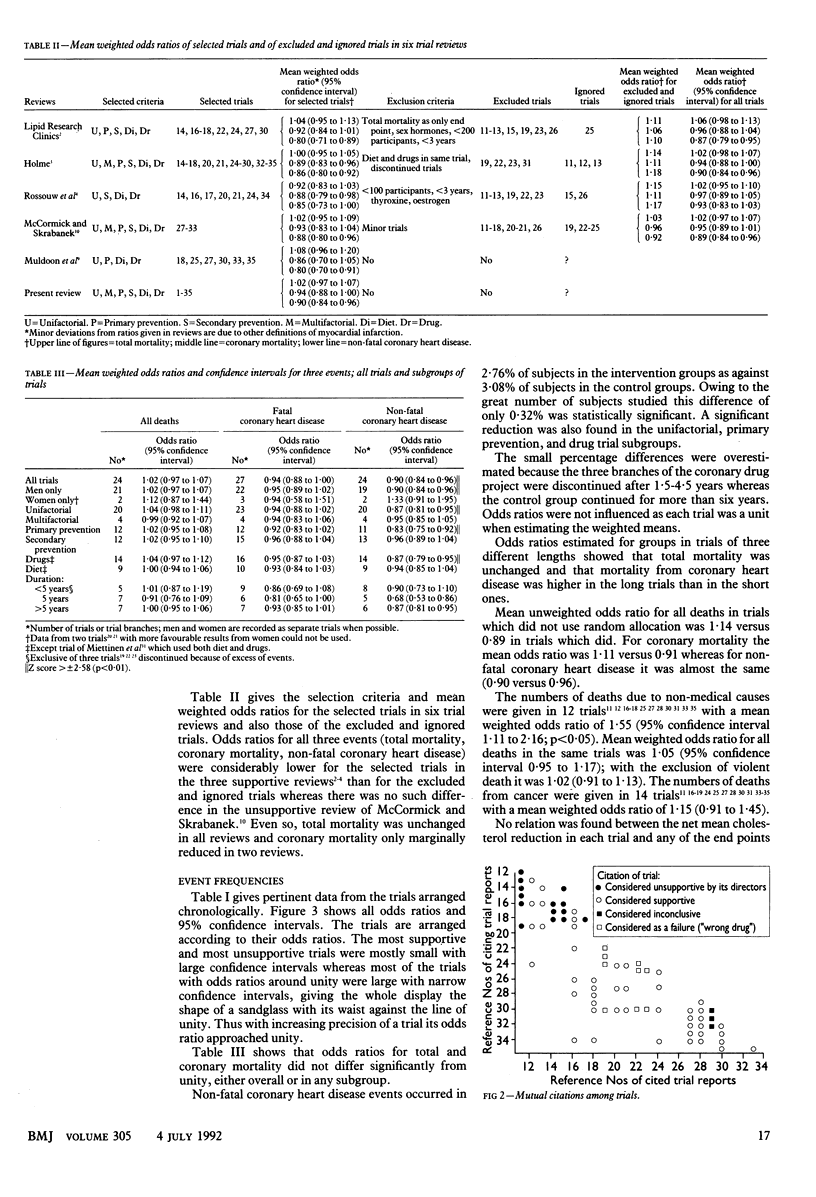

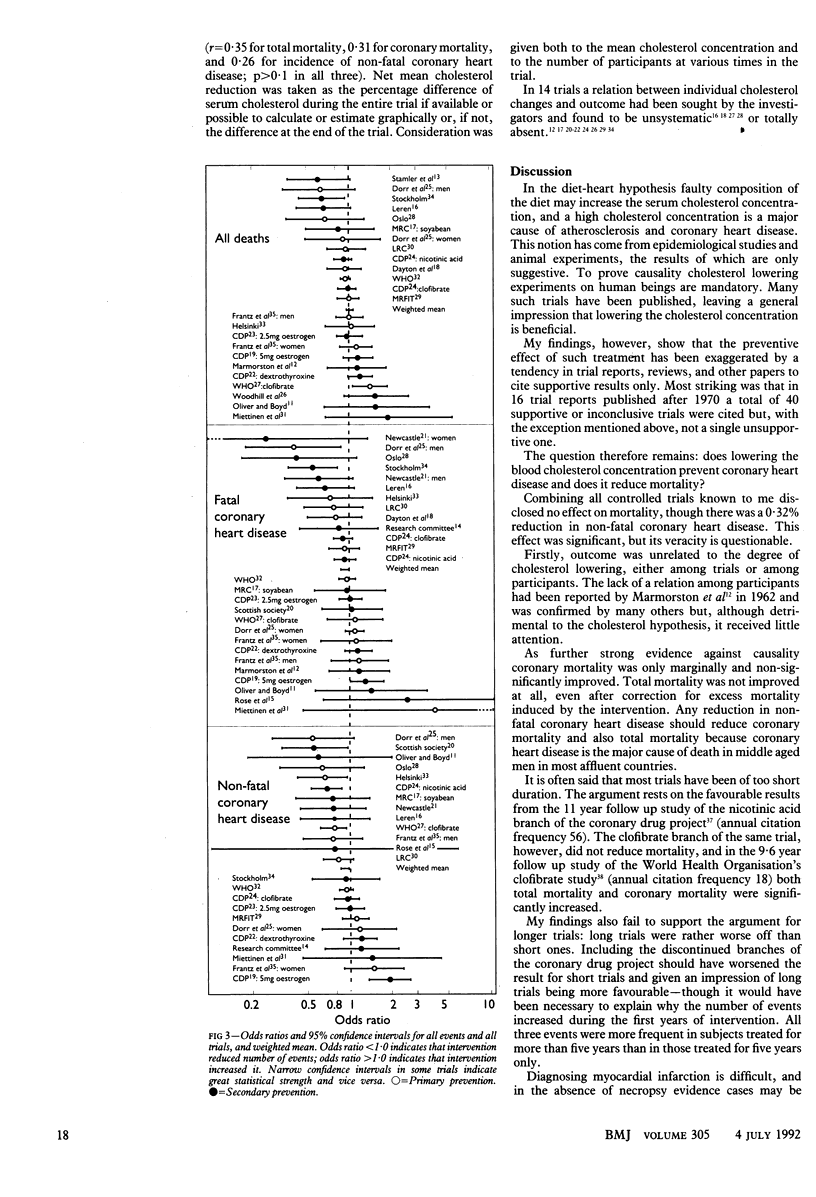

OBJECTIVE--To see if the claim that lowering cholesterol values prevents coronary heart disease is true or if it is based on citation of supportive trials only. DESIGN--Comparison of frequency of citation with outcome of all controlled cholesterol lowering trials using coronary heart disease or death, or both, as end point. SUBJECTS--22 controlled cholesterol lowering trials. RESULTS--Trials considered by their directors as supportive of the contention were cited almost six times more often than others, according to Science Citation Index. Apart from trials discontinued because of alleged side effects of treatment, unsupportive trials were not cited after 1970, although their number almost equalled the number considered supportive. In three supportive reviews the outcome of the selected trials was more favourable than the outcome of the excluded and ignored trials. In the 22 controlled cholesterol lowering trials studied total and coronary heart disease mortality was not changed significantly either overall or in any subgroup. A statistically significant 0.32% reduction in non-fatal coronary heart disease seemed to be due to bias as event frequencies were unrelated to trial length and to mean net reduction in cholesterol value; individual changes in cholesterol values were unsystematically or not related to outcome; and after correction for a small but significant increase in non-medical deaths in the intervention groups total mortality remained unchanged (odds ratio 1.02). CONCLUSIONS--Lowering serum cholesterol concentrations does not reduce mortality and is unlikely to prevent coronary heart disease. Claims of the opposite are based on preferential citation of supportive trials.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Canner P. L., Berge K. G., Wenger N. K., Stamler J., Friedman L., Prineas R. J., Friedewald W. Fifteen year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986 Dec;8(6):1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson L. A., Rosenhamer G. Reduction of mortality in the Stockholm Ischaemic Heart Disease Secondary Prevention Study by combined treatment with clofibrate and nicotinic acid. Acta Med Scand. 1988;223(5):405–418. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1988.tb15891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorr A. E., Gundersen K., Schneider J. C., Jr, Spencer T. W., Martin W. B. Colestipol hydrochloride in hypercholesterolemic patients--effect on serum cholesterol and mortality. J Chronic Dis. 1978 Jan;31(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterbrook P. J., Berlin J. A., Gopalan R., Matthews D. R. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991 Apr 13;337(8746):867–872. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz I. D., Jr, Dawson E. A., Ashman P. L., Gatewood L. C., Bartsch G. E., Kuba K., Brewer E. R. Test of effect of lipid lowering by diet on cardiovascular risk. The Minnesota Coronary Survey. Arteriosclerosis. 1989 Jan-Feb;9(1):129–135. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.9.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick M. H., Elo O., Haapa K., Heinonen O. P., Heinsalmi P., Helo P., Huttunen J. K., Kaitaniemi P., Koskinen P., Manninen V. Helsinki Heart Study: primary-prevention trial with gemfibrozil in middle-aged men with dyslipidemia. Safety of treatment, changes in risk factors, and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1987 Nov 12;317(20):1237–1245. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711123172001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holme I. An analysis of randomized trials evaluating the effect of cholesterol reduction on total mortality and coronary heart disease incidence. Circulation. 1990 Dec;82(6):1916–1924. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.6.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones R., Rawlins M. D. Prescribing at the interface between hospitals and general practitioners. BMJ. 1992 Jan 4;304(6818):4–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6818.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRosa J. C., Hunninghake D., Bush D., Criqui M. H., Getz G. S., Gotto A. M., Jr, Grundy S. M., Rakita L., Robertson R. M., Weisfeldt M. L. The cholesterol facts. A summary of the evidence relating dietary fats, serum cholesterol, and coronary heart disease. A joint statement by the American Heart Association and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The Task Force on Cholesterol Issues, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1990 May;81(5):1721–1733. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.5.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leren P. The effect of plasma cholesterol lowering diet in male survivors of myocardial infarction. A controlled clinical trial. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1966;466:1–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick J., Skrabanek P. Coronary heart disease is not preventable by population interventions. Lancet. 1988 Oct 8;2(8615):839–841. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen T. A., Huttunen J. K., Naukkarinen V., Strandberg T., Mattila S., Kumlin T., Sarna S. Multifactorial primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in middle-aged men. Risk factor changes, incidence, and mortality. JAMA. 1985 Oct 18;254(15):2097–2102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muldoon M. F., Manuck S. B., Matthews K. A. Lowering cholesterol concentrations and mortality: a quantitative review of primary prevention trials. BMJ. 1990 Aug 11;301(6747):309–314. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6747.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OLIVER M. F., BOYD G. S. Influence of reduction of serum lipids on prognosis of coronary heart-disease. A five-year study using oestrogen. Lancet. 1961 Sep 2;2(7201):499–505. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(61)92951-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver M. F. Doubts about preventing coronary heart disease. BMJ. 1992 Feb 15;304(6824):393–394. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6824.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSE G. A., THOMSON W. B., WILLIAMS R. T. CORN OIL IN TREATMENT OF ISCHAEMIC HEART DISEASE. Br Med J. 1965 Jun 12;1(5449):1531–1533. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5449.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M. C. Sir John Scott Burdon-Sanderson (1828-1905): a pioneer in electrophysiology. Circulation. 1969 Jul;40(1):1–2. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.40.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw J. E., Lewis B., Rifkind B. M. The value of lowering cholesterol after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1990 Oct 18;323(16):1112–1119. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199010183231606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehbens W. E. Diet and atherogenesis. Nutr Rev. 1989 Jan;47(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1989.tb02743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhill J. M., Palmer A. J., Leelarthaepin B., McGilchrist C., Blacket R. B. Low fat, low cholesterol diet in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1978;109:317–330. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-0967-3_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S., Peto R., Lewis J., Collins R., Sleight P. Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1985 Mar-Apr;27(5):335–371. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(85)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarling E. J., Sexton H., Milnor P., Jr Failure to diagnose acute myocardial infarction. The clinicopathologic experience at a large community hospital. JAMA. 1983 Sep 2;250(9):1177–1181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]