Abstract

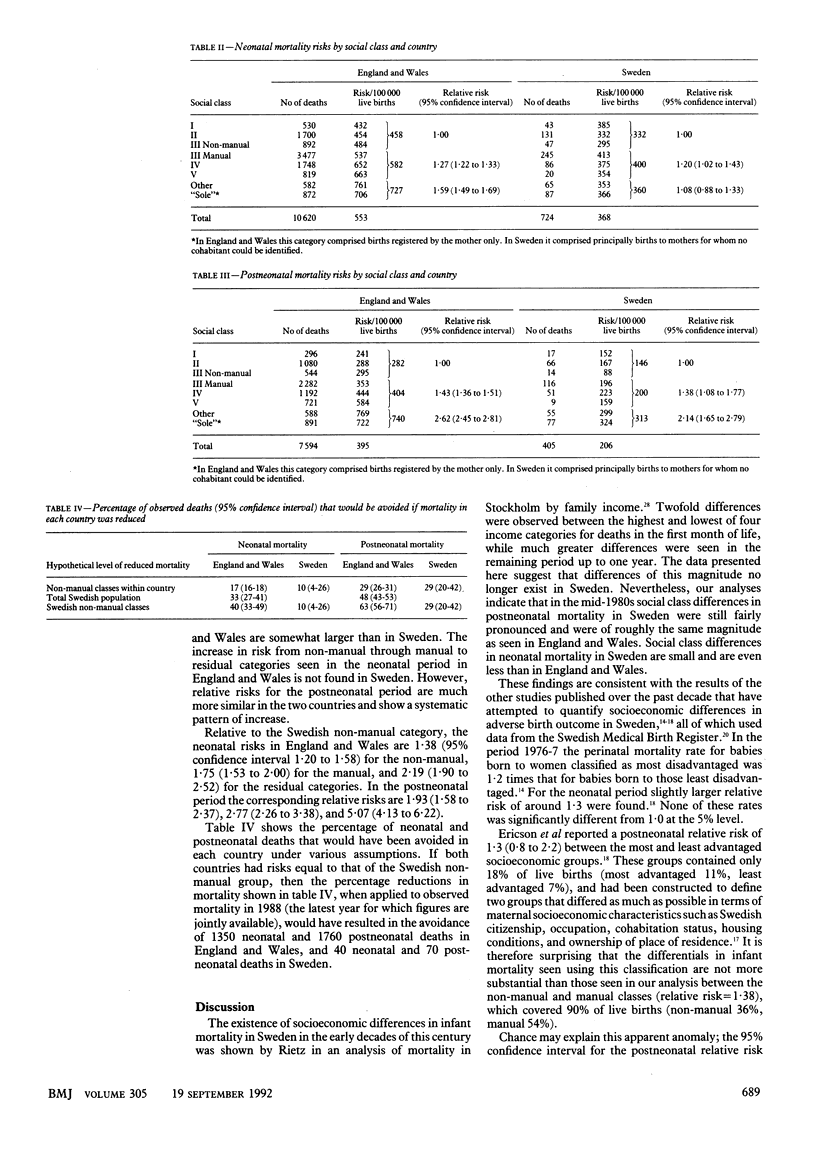

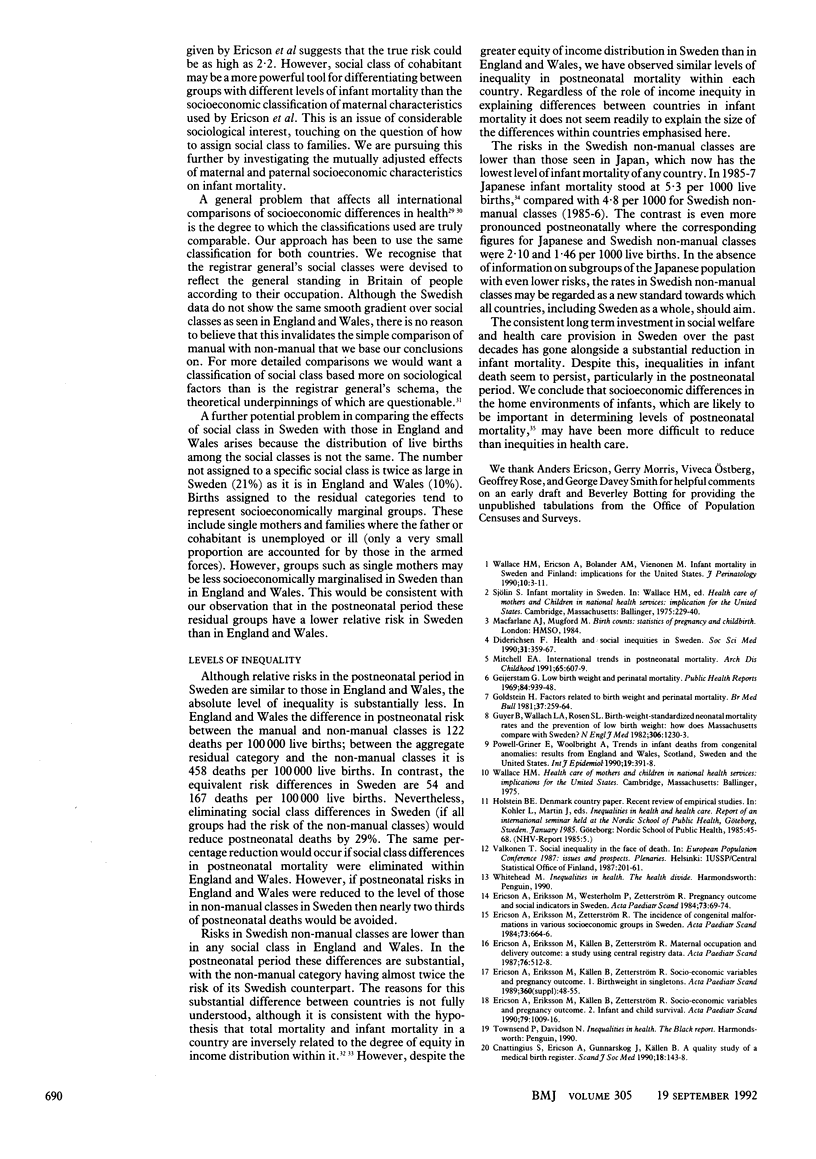

OBJECTIVES--To investigate social class differences in infant mortality in Sweden in the mid-1980s and to compare their magnitude with that of those found in England and Wales. DESIGN--Analysis of risk of infant death by social class in aggregated routine data for the mid-1980s, which included the linkage of Swedish births to the 1985 census. SETTING--Sweden and England and Wales. SUBJECTS--All live births in Sweden (1985-6) and England and Wales (1983-5) and corresponding infant deaths were analysed. The Swedish data were coded to the British registrar general's social class schema. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Risk of death in the neonatal and postneonatal period. RESULTS--Taking the non-manual classes as the reference group, in the neonatal period in Sweden the manual social classes had a relative risk for mortality of 1.20 (95% confidence interval 1.02 to 1.43) and those not classified into a social class a relative risk of 1.08 (0.88 to 1.33). In the postneonatal period the equivalent relative risks were 1.38 (1.08 to 1.77) for manual classes and 2.14 (1.65 to 2.79) for the residual; these are similar to those for England and Wales (1.43 (1.36 to 1.51) for manual classes, 2.62 (2.45 to 2.81) for the residual). CONCLUSIONS--The existence of an equitable health care system and a strong social welfare policy in Sweden has not eliminated inequalities in post-neonatal mortality. Furthermore, the very low risk of infant death in the Swedish non-manual group (4.8/1000 live births) represents a target towards which public health interventions should aim. If this rate prevailed in England and Wales, 63% of postneonatal deaths would be avoided.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Cnattingius S., Ericson A., Gunnarskog J., Källén B. A quality study of a medical birth registry. Scand J Soc Med. 1990 Jun;18(2):143–148. doi: 10.1177/140349489001800209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diderichsen F. Health and social inequities in Sweden. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31(3):359–367. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90283-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson A., Eriksson M., Källén B., Zetterström R. Socio-economic variables and pregnancy outcome. 2. Infant and child survival. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1990 Nov;79(11):1009–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1990.tb11376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson A., Eriksson M., Källén B., Zetterström R. Socio-economic variables and pregnancy outcome. Birthweight in singletons. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl. 1989;360:48–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1989.tb11282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson A., Eriksson M., Westerholm P., Zetterström R. Pregnancy outcome and social indicators in Sweden. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1984 Jan;73(1):69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1984.tb09900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson A., Eriksson M., Zetterström R. The incidence of congenital malformations in various socioeconomic groups in Sweden. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1984 Sep;73(5):664–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1984.tb09992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijerstam G. Low birth weight and perinatal mortality. Public Health Rep. 1969 Nov;84(11):939–948. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H. Factors related to birth weight and perinatal mortality. Br Med Bull. 1981 Sep;37(3):259–264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. Variance estimators for attributable fraction estimates consistent in both large strata and sparse data. Stat Med. 1987 Sep;6(6):701–708. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780060607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer B., Wallach L. A., Rosen S. L. Birth-weight-standardized neonatal mortality rates and the prevention of low birth weight: how does Massachusetts compare with Sweden? N Engl J Med. 1982 May 20;306(20):1230–1233. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198205203062011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illsley R. Health inequities in Europe. Comparative review of sources, methodology and knowledge. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31(3):229–236. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell E. A. International trends in postneonatal mortality. Arch Dis Child. 1990 Jun;65(6):607–609. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.6.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y., Nagai M., Yanagawa H. A characteristic change in infant mortality rate decrease in Japan. Public Health. 1991 Mar;105(2):145–151. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(05)80289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pharoah P. O., Morris J. N. Postneonatal Mortality. Epidemiol Rev. 1979;1:170–183. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell-Griner E., Woolbright A. Trends in infant deaths from congenital anomalies: results from England and Wales, Scotland, Sweden and the United States. Int J Epidemiol. 1990 Jun;19(2):391–398. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quine S. Problems in comparing findings on social class cross-culturally--applied to infant mortality (Australia and Britain). Soc Sci Med. 1990;30(12):1283–1288. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90308-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vågerö D., Lundberg O. Health inequalities in Britain and Sweden. Lancet. 1989 Jul 1;2(8653):35–36. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace H. M., Ericsson A., Bolander A. M., Vienonen M. Infant mortality in Sweden and Finland: implications for the United States. J Perinatol. 1990 Mar;10(1):3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson R. G. Income distribution and life expectancy. BMJ. 1992 Jan 18;304(6820):165–168. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6820.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]