Abstract

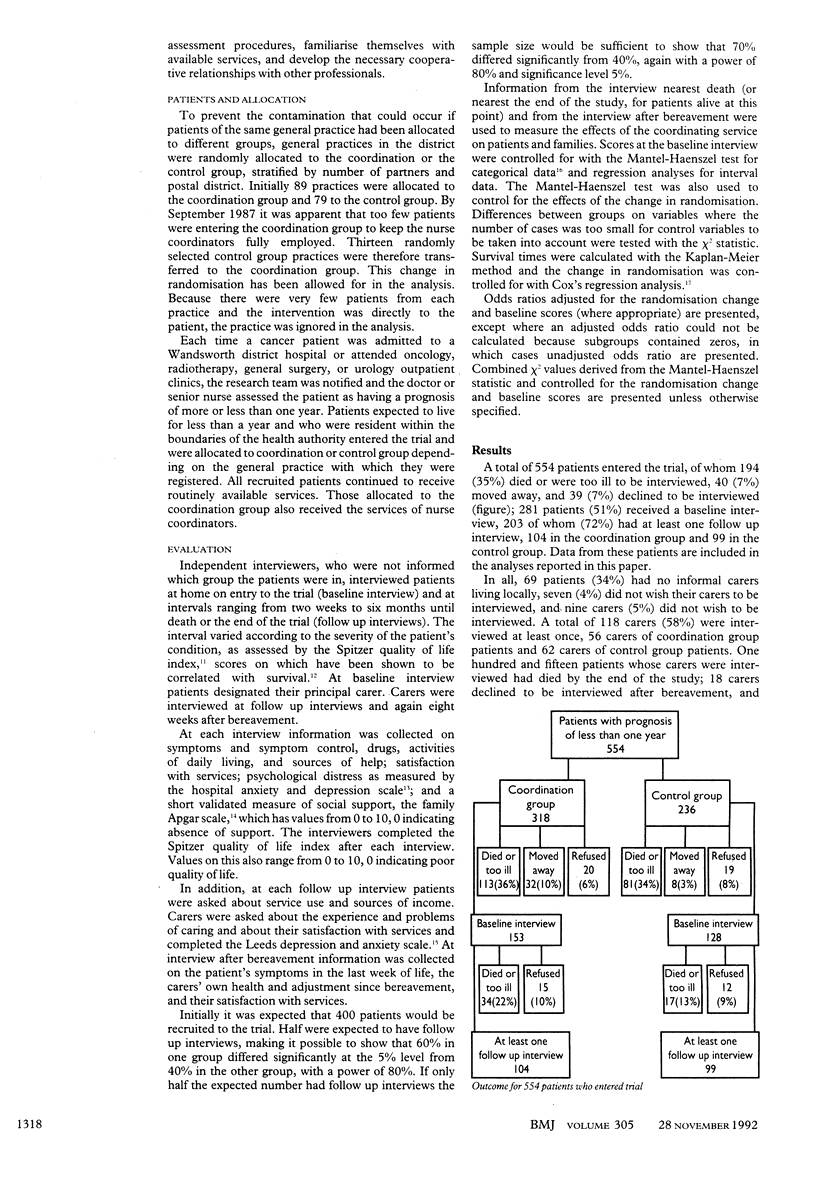

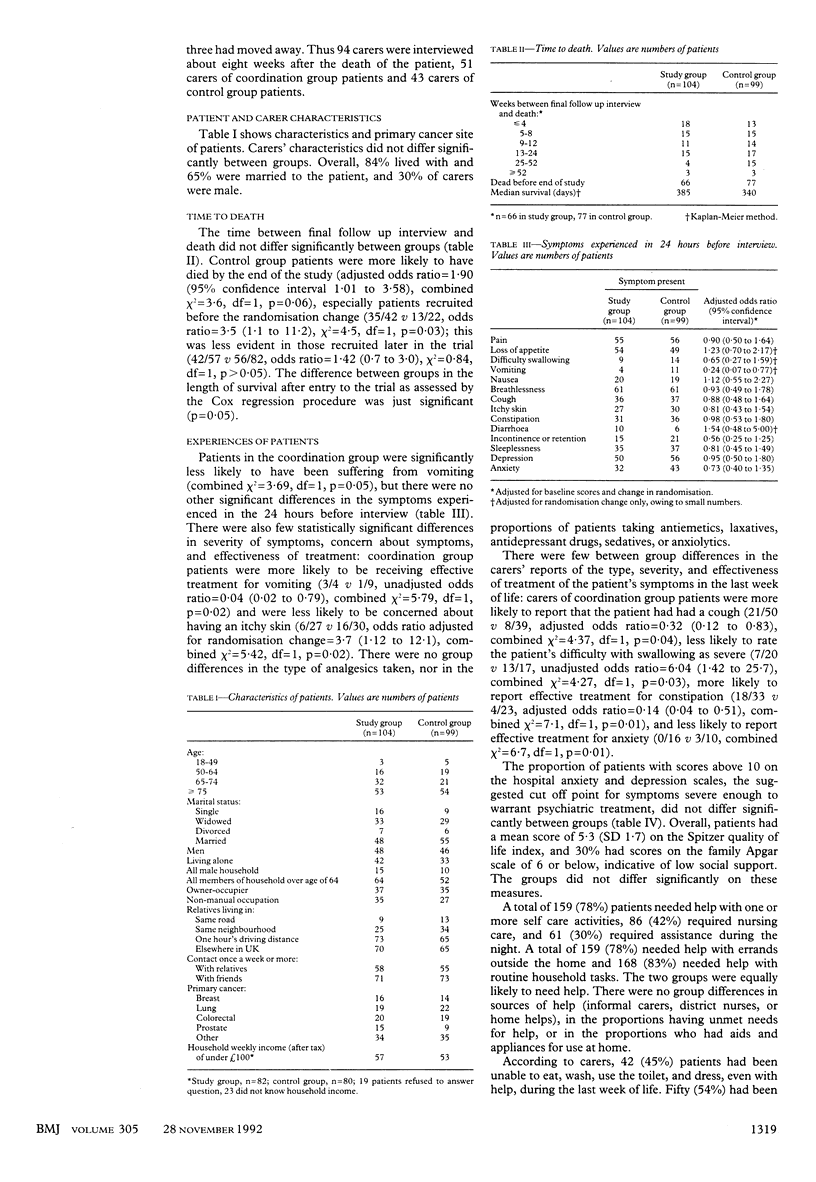

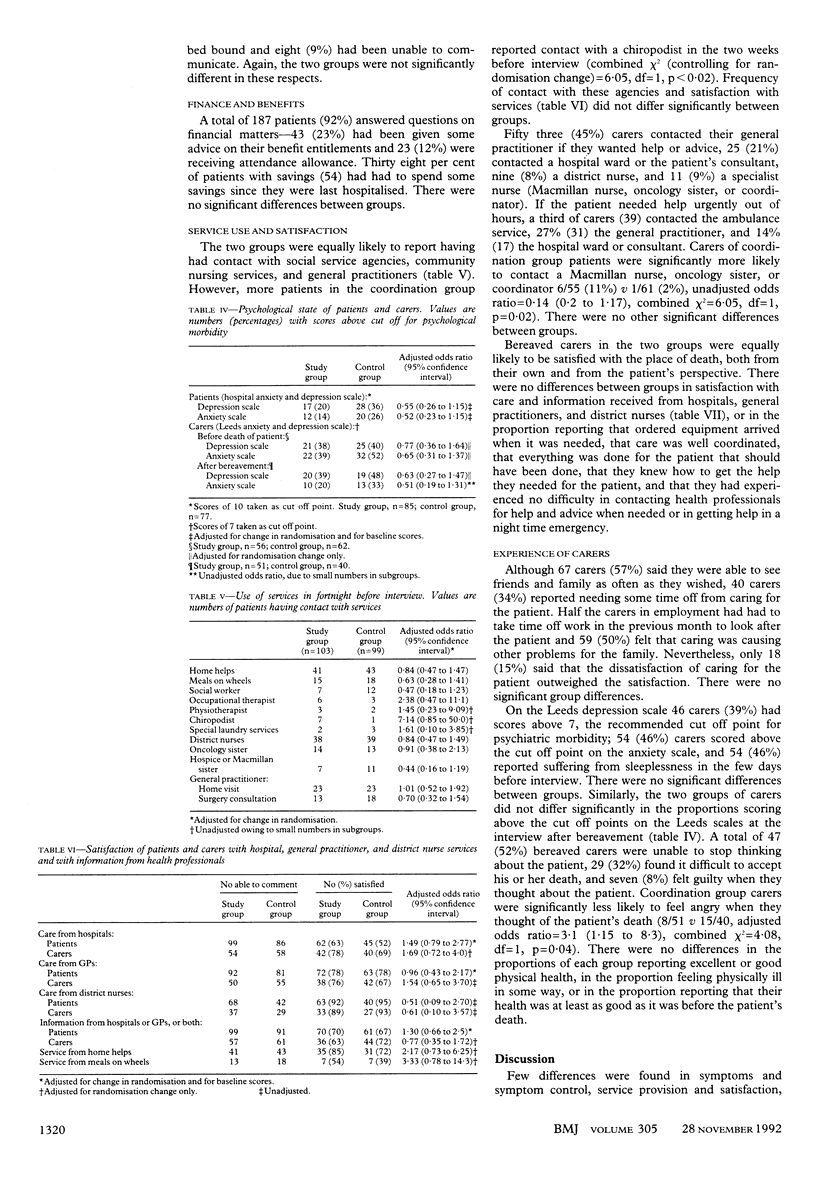

OBJECTIVES--To measure effects on terminally ill cancer patients and their families of coordinating the services available within the NHS and from local authorities and the voluntary sector. DESIGN--Randomised controlled trial. SETTING--Inner London health district. PATIENTS--Cancer patients were routinely notified from 1987 to 1990. 554 patients expected to survive less than one year entered the trial and were randomly allocated to a coordination or a control group. INTERVENTION--All patients received routinely available services. Coordination group patients received the assistance of two nurse coordinators, whose role was to ensure that patients received appropriate and well coordinated services, tailored to their individual needs and circumstances. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Patients and carers were interviewed at home on entry to the trial and at intervals until death. Interviews after bereavement were also conducted. Outcome measures included the presence and severity of physical symptoms, psychiatric morbidity, use of and satisfaction with services, and carers' problems. Results from the baseline interview, the interview closest to death, and the interview after bereavement were analysed. RESULTS--Few differences between groups were significant. Coordination group patients were less likely to suffer from vomiting, were more likely to report effective treatment for it, and less likely to be concerned about having an itchy skin. Their carers were more likely to report that in the last week of life the patient had had a cough and had had effective treatment for constipation, and they were less likely to rate the patient's difficulty swallowing as severe or to report effective treatment for anxiety. Coordination group patients were more likely to have seen a chiropodist and their carers were more likely to contact a specialist nurse in a night time emergency. These carers were less likely to feel angry about the death of the patient. CONCLUSIONS--This coordinating service made little difference to patient or family outcomes, perhaps because the service did not have a budget with which it could obtain services or because the professional skills of the nurse-coordinators may have conflicted with the requirements of the coordinating role.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Higginson I., Wade A., McCarthy M. Palliative care: views of patients and their families. BMJ. 1990 Aug 4;301(6746):277–281. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6746.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockley J. M., Dunlop R., Davies R. J. Survey of distressing symptoms in dying patients and their families in hospital and the response to a symptom control team. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988 Jun 18;296(6638):1715–1717. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6638.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houts P. S., Yasko J. M., Harvey H. A., Kahn S. B., Hartz A. J., Hermann J. F., Schelzel G. W., Bartholomew M. J. Unmet needs of persons with cancer in Pennsylvania during the period of terminal care. Cancer. 1988 Aug 1;62(3):627–634. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880801)62:3<627::aid-cncr2820620331>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley R. E. Toward a behavioral model of the physician as case manager. Soc Sci Med. 1986;23(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(86)90326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane R. L., Wales J., Bernstein L., Leibowitz A., Kaplan S. A randomised controlled trial of hospice care. Lancet. 1984 Apr 21;1(8382):890–894. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91349-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunt B., Hillier R. Terminal care: present services and future priorities. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981 Aug 29;283(6291):595–598. doi: 10.1136/bmj.283.6291.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. N., Sherwood S. Quality of life of cancer patients at different stages in the disease trajectory. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(6):545–556. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp C. A., Chamberlain R. Case management services for the chronically mentally ill. Soc Work. 1985 Sep-Oct;30(5):417–422. doi: 10.1093/sw/30.5.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seale C. F. What happens in hospices: a review of research evidence. Soc Sci Med. 1989;28(6):551–559. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd G. Case management. Health Trends. 1990;22(2):59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smilkstein G., Ashworth C., Montano D. Validity and reliability of the family APGAR as a test of family function. J Fam Pract. 1982 Aug;15(2):303–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaith R. P., Bridge G. W., Hamilton M. The Leeds scales for the self-assessment of anxiety and depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1976 Feb;128:156–165. doi: 10.1192/bjp.128.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer W. O., Dobson A. J., Hall J., Chesterman E., Levi J., Shepherd R., Battista R. N., Catchlove B. R. Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: a concise QL-index for use by physicians. J Chronic Dis. 1981;34(12):585–597. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(81)90058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes E. Dying now. Lancet. 1984 Apr 28;1(8383):950–952. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond A. S., Snaith R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983 Jun;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]