Short abstract

Can randomised controlled trials be successfully conducted over the internet? The authors report a feasibility study of such a trial in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee

The possibility of conducting clinical trials entirely on line is an enticing but relatively unexplored medical application of the internet. The penetrance of the internet in the population offers the possibility of rapid recruitment of participants, and technological advances enable instant collection of data in a secure and confidential manner.1 These attributes could theoretically accelerate the evaluation of many compounds by cutting costs and reducing the duration of each study. Many components of an online trial, such as recruitment websites and electronic data capture technologies, have been separately described,2–4 but few attempts have been made to integrate these into a single process, and no study has evaluated the performance of such an endeavour.

What were we trying to accomplish?

We set out to explore these issues by attempting a prototype double blind randomised placebo controlled trial in people recruited and followed entirely over the internet. The underlying intention in the design was to translate, as far as possible, all elements of a rigorous randomised placebo controlled trial into the virtual domain. To maximise the chance of success we chose to test glucosamine, a safe nutritional product popularly taken for symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knee,5 by using a trial design appropriate for this purpose. We designed a 14 week (2 week run-in, 12 week intervention) internet based placebo controlled randomised trial of glucosamine with biweekly scheduled online assessments of knee pain with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) as the primary outcome measure.6 The WOMAC was developed and validated as a self report questionnaire, can be used on a computer screen, and is recommended as a primary outcome for osteoarthritis trials.6–8

What would constitute success?

Three attributes are essential for online trials to be methodologically appealing: feasibility, efficiency, and validity. Determinants of these aspects for an internet based trial include recruitment rates, ability to authenticate applicants, generalisability of participants' characteristics, variance of the primary outcome measure, adherence, and participant satisfaction. We therefore set ourselves the following objectives: (a) to recruit 200 people for whom we could document osteoarthritis of the knee meeting established criteria9; (b) to enrol them into a 14 week prototype randomised placebo controlled trial; and (c) to achieve > 80% retention and > 80% adherence to the drug. We believed that the approach would merit further consideration if these objectives could be met, the sample resembled those in traditional trials of osteoarthritis of the knee, and the cost of the online trial was substantially less than if it had been done in a traditional setting.

Summary points

The possibility of conducting clinical trials on line is a relatively unexplored application of the internet

For online trials to be methodologically appealing they must be feasible, efficient, and valid

More than 1200 people applied on line to take part in a trial of glucosamine in osteoarthritis of the knee

Of 205 participants randomised, approximately 80% completed the trial

The estimated cost of the trial was about half that of a hospital based approach

The requirement for written consent and medical records slowed down the progress of the trial

Most participants had a positive view of the trial and would be happy to participate in another such trial in the future

How was the trial done over the internet?

Architecture of the study website

We constructed a website to solicit participants and conduct the trial. The site was situated on an independent server within the Boston University School of Medicine domain. We protected participants' data with encryption, passwords, and a firewall. The public area of the website had hypertext links to a consent form and an eligibility screening page, and the participant-only pages contained questionnaires and provided utilities. Two key elements of our website were a batching utility that sent email reminders and a time sensitive code that presented the appropriate questionnaires to participants.

Recruitment, authentication, and enrolment

The website administered an automated screening questionnaire and provided detailed information about the study and investigators. We required applicants to download and send us (by mail) the signed consent and medical record release forms. Participants had to fulfil eligibility criteria as documented from the questions posed over the internet combined with information from radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging scans, or medical reports.

Prototype randomised placebo controlled trial

The run-in phase of the trial started with email or telephone interactions between the coordinator and each participant, followed by completion of an online baseline evaluation questionnaire. We asked participants to return to the website between one and two weeks later to complete a second questionnaire that triggered randomisation and dispensing of study pills. Staff otherwise uninvolved with the trial did the randomisation and labelling of the pill bottles. Only a code number on the label identified the pills to the study staff. We sent these to participants by express mail at monthly intervals.

We asked participants to log in every two weeks to complete online questionnaires, including the WOMAC questionnaire6,7 and self reported pill counts. We prompted them to do this by automated reminder emails and personalised schedules. We sent out paper calendars to record daily use of analgesics and other drugs. We also asked them to report adverse experiences at any time by using the website, email, or our toll-free telephone number.

Post-trial survey

We sent a survey to each participant on completion. This asked about their internet access, their level of satisfaction with the process, the responsiveness of study staff, and how reliably participants had taken their study pills.

How did we plan to assess performance of the trial?

We used descriptive data and a CONSORT diagram for our initial evaluations.10 As no gold standard exists for evaluating characteristics of participants, we opted to compare our sample with those in traditionally conducted trials. To do this, we did a systematic search for trials of osteoarthritis of the knee that reported data on age, sex, and WOMAC scores and were published in rheumatology journals in 2000-2. To report retention rates, we used the last visit completed by participants as the point at which they discontinued participation. To estimate adherence we compared self reported pill counts with the expected number of remaining pills. Finally, we obtained independent estimates from the Tufts-New England Medical Center office of research administration of the costs of the trial when done both in an internet based setting and in a traditional setting.

How did the internet based trial perform?

Solicitation of applicants

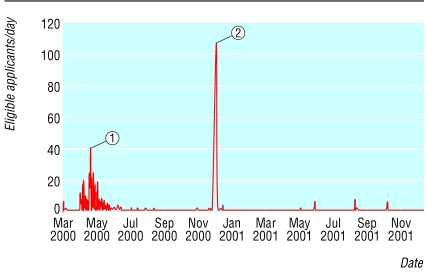

In March 2000 Remedy magazine published an article about the study that resulted in more than 750 screened applicants accumulating in our database (fig 1 and fig 2). In November 2000 we used a commercial service to email our advertisement to approximately 2 million recipients, resulting in a further 350 applications. Two notable differences between the two methods were that the magazine article resulted in more sustained response (approximately two months v two weeks), whereas the electronic mailing produced a larger daily number of applicants (maximum 107/day v 40/day).

Fig 1.

Accrual of applicants passing the first eligibility screen. 1=appearance of article in Remedy magazine publicising the study; 2=secondary reporting of Remedy magazine publicity in electronic media; 3=advertisement in Ezine mass emailing

Fig 2.

Rate of accrual of applicants passing first eligibility screen. 1=application after appearance of article in Remedy magazine publicising the study; 2=advertisement in Ezine mass emailing

Enrolment

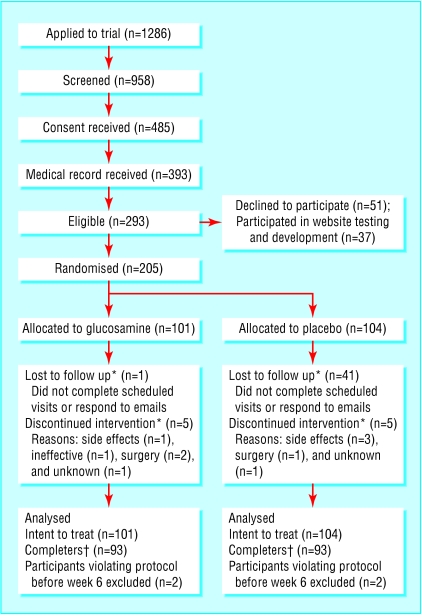

A decrement occurred at each step in the flow of recruitment and enrolment (fig 3). Of 958 applicants who passed the first eligibility screen, 485 (51%) sent us a signed hard copy consent form and medical record release. Ultimately, we confirmed osteoarthritis of the knee for 293 applicants, of whom 205 participated in the trial (table A on bmj.com). The mean age of participants was 60.2 (SD 9.4, range 44-98) years, 64% were women, 90% were Caucasian, 80% reported use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesics, and the mean body mass index of participants was 32.6 (SD 8.5) kg/m2. Mean WOMAC subscale scores at baseline were 8.9 (SD 3.4) for pain, 30.9 (12.0) for physical function, and 4.1 (1.6) for stiffness. Median time from application to receipt of consent was 13 (interquartile range 6-25) days, and median time from receipt of consent to procurement of medical records was 30 (21-56) days.

Fig 3.

Flow of participants through the trial. *Before week 6. †Includes people who participated at least through week 6

Comparison with traditional trials

We found four traditional osteoarthritis trials that met our criteria, comprising 1252 participants, with a range of duration from six weeks to 16 weeks (table 1).11–14 Compared with these trials, our sample had fewer women (64% v median of 75%) and higher body mass index (32.6 v 31.3 kg/m2) but was within represented ranges for age, retention rates, WOMAC scores, and variance in WOMAC scores.

Table 1.

Comparison of selected characteristics between online glucosamine trial and traditional clinic based clinical trials of osteoarthritis of the knee

|

Clinic based trials

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Online glucosamine trial | McKenna et al (2001)14 | Fransen et al (2001)13 | Baker et al (2001)12 | Pelletier et al (2000)11 |

| Sample size | 205 | 600 | 126 | 46 | 480 |

| Dropout rate (%) | 23.9 | 25.0 | 15.1 | 15.2 | 34.6 |

| Mean (SD) age | 60.2 (9.4) | 61.7* | 66.1 (10.3) | 68.5 (6) | 63.5 (8.9) |

| Mean (SD) body mass index | 32.6 (8.5) | NR | 29.4 (5.0) | 31.5 (4.5) | 31.3 (5.7) |

| Female (%) | 64.4 | 65.3 | 73.0 | 78.0 | 79.6 |

| Use of NSAIDs (%) | 79.5 | 77.8 | NR | 39.0 | NR |

| Mean (SD) WOMAC pain score | 44.5 (17.0)† | 53.4 (15.9) | 37.8 (19.5) | 40.9 (18.0) | NR |

| Mean (SD) WOMAC global score | 46.0 (16.7)† | 55.1 (15.2) | NR | NR | 73.6 (24.6) |

NR=not reported; NSAID=non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; WOMAC=Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index.

No standard deviations reported.

Based on Likert scores transformed on to a 0-100 scale.

Cost comparison

Our cost estimation for the online and hospital based approaches for the same trial assumed a single centre design, a two year duration, equal investigator and coordinator inputs, and three months' full time work by a computer programmer to build the website. This suggested a cost of $914 (£565, €796) per participant for the online trial compared with $1925 for the hospital based approach. The difference was driven by need for clinical space, nursing time, participant travel reimbursements, and data entry. The cost of the hospital based approach increased if (as seems likely) the duration was longer or a multicentre approach was needed. However, we would advocate a formal cost analysis to evaluate this issue more thoroughly.

Results: adherence, satisfaction, and WOMAC scores

The participants completed 78% their 1230 scheduled online visits. Overall retention was 88% at 10 weeks and 76% at 12 weeks. According to the self reported pill counts, 134 (77%) participants took at least 90% of their pills and 150 (86%) took at least 80%. One hundred and fifty six (76%) participants completed the post-trial survey. Overall, the responses were very positive (table 2). WOMAC pain scores showed regression to the mean, with no substantial difference between the glucosamine and placebo groups with respect to change in WOMAC pain score (– 2.3 v – 2.8, P = 0.41).

Table 2.

Results from the post-trial survey (n=156)

| Responses | No (%) |

|---|---|

| How often did you take the study medication as directed? | |

| Some of the time | 2 (1.3) |

| Most of the time | 32 (20.5) |

| All of the time | 122 (78.2) |

| Did you feel that someone was available to help you if you experienced problems during the trial? | |

| Never | 2 (1.3) |

| Sometimes | 6 (3.8) |

| Usually | 44 (28.2) |

| Always | 104 (66.7) |

| Would you have preferred to go to a study centre for visits rather than complete study visits over the internet? | |

| No | 129 (82.7) |

| Sometimes | 17 (10.9) |

| Yes | 10 (6.4) |

| If you could, would you take part in other online trials? | |

| No | 2 (1.3) |

| Maybe | 17 (10.9) |

| Yes | 137 (87.8) |

| Where did you most often access the online glucosamine trial? | |

| Home | 131 (84.0) |

| Work | 17 (10.9) |

| Library | 2 (1.3) |

| Other | 6 (3.8) |

| Overall, how would you rate your experience with the online glucosamine trial? | |

| Very negative | 0 |

| Negative | 4 (2.6) |

| Neutral | 18 (11.8) |

| Positive | 61 (40.1) |

| Very positive | 69 (45.4) |

How successful was the prototype trial?

It is clearly feasible to do certain types of randomised placebo controlled trials over the internet. We were able to solicit and authenticate applicants and to conduct the internet based trial with adherence and retention rates comparable to those of trials done in traditional settings. Furthermore, our participants reported high levels of satisfaction and willingness to participate in similar trials in the future.

The trial was efficient with respect to the application rates, direct data entry, short time to database lock, and minimal staffing levels. On the other hand, the time taken to obtain consent and medical records limited the speed of enrolment. These were two aspects of our method that were not internet based. Although the large number of applicants offset the delay, it could be improved by measures to circumvent the need for paper documents and medical records. We were also not able to tackle the issue of scalability in this single trial.

The decrement in numbers at each step of the application process may have reduced the external validity of our sample (fig 3). Although our participants seemed broadly similar to those in comparable traditional trials, the requirement for internet access probably resulted in a sample of higher educational level. External validity is also a common problem for traditional trials, owing to restrictive eligibility criteria and selection biases in hospital based settings, whereas the internet based approach allows participation from the home or workplace. In either case, the problem needs to be tackled by an adequate description of the setting and sample characteristics.15

In principle, considerations about generalisability should not affect the internal validity inherent in a well performed randomised controlled clinical trial. We used epidemiological methods for case confirmation and a self report assessment of disease severity validated for computer use.7,9 However, we relied on self reported pill counts that may be less reliable than those done by a research nurse. Future internet based trials could assess this aspect more robustly through the use of returned blister packs or other technologies. The fact that the WOMAC pain scores, and their variability, were similar to those in traditional trials provides further evidence for the construct validity of this method. Also, we detected regression to the mean by using this measure and obtained a (negative) result concordant with recent independent trials of this compound.16–18

Recommendations

We recognise that several unique factors may have contributed to the successful elements of this internet based trial. Further explorations may be needed to determine to what extent our findings can be reproduced for other interventions and medical disorders. On the basis of current knowledge, we suggest that the internet based trial method is most suitable when the intervention is safe, the medical disorder can be confirmed by remote means, and the outcome measures can be applied by using electronically transmissible technologies. Within these parameters, the internet trial method offers opportunities for studying treatments quickly and efficiently.

Supplementary Material

An extra table appears on bmj.com

An extra table appears on bmj.com

We thank Leslie Lenert for his helpful suggestions and Leanne Hitzl for doing the cost computations.

Contributors: TMcA was the principal investigator and is the guarantor. MF assisted with the design and epidemiological aspects of the study. KK did the technical design and assembly of the study website. MLaV did the statistical analysis. ML assisted with the design and development of the trial procedures.

Funding: This study was supported initially by a grant from the Arthritis Foundation and subsequently through support from the National Library of Medicine (RO-1 LM06856-01).

Competing interests: A business process patent (USA only) in respect of performing clinical trials over the internet filed by Boston University is under appeal. TMcA and KK are named in the patent application. Rotta Pharmaceuticals supplied some of the glucosamine and placebo powder for the online trial.

Ethical approval: Boston University School of Medicine institutional review board approved the overall study, including the prototype trial.

References

- 1.Carey VJ. Using hypertext and the internet for structure and management of observational studies. Stat Med 1997;16: 1667-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly MA, Oldham J. The internet and randomised controlled trials. Int J Med Inf 1997;47: 91-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edworthy SM. World wide web: opportunities, challenges, and threats. Lupus 1999;8: 596-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marks R, Bristol H, Conlon M, Pepine CJ. Enhancing clinical trials on the internet: lessons from INVEST. Clin Cardiol 2001;24(11 suppl): V17-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McAlindon TE, LaValley MP, Gulin JP, Felson DT. Glucosamine and chondroitin for treatment of osteoarthritis: a systematic quality assessment and meta-analysis. JAMA 2000;283: 1469-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellamy N, Campbell J, Stevens J, Pilch L, Stewart C, Mahmood Z. Validation study of a computerized version of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities VA3.0 osteoarthritis index. J Rheumatol 1997;24: 2413-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theiler R, Spielberger J, Bischoff HA, Bellamy N, Huber J, Kroesen S. Clinical evaluation of the WOMAC 3.0 OA index in numeric rating scale format using a computerized touch screen version. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2002;10: 479-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altman R, Brandt KD, Hochberg MC, Moskowitz R. Design and conduct of clinical trials in patients with osteoarthritis: recommendations from a task force of the Osteoarthritis Research Society. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 1996;4: 217-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altman RD. Criteria for classification of clinical osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl 1991;27: 10-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray GD. Promoting good research practice. Stat Methods Med Res 2000;9: 17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelletier JP, Yaron M, Haraoui B, Cohen P, Nahir MA, Choquette D, et al. Efficacy and safety of diacerein in osteoarthritis of the knee: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43: 2339-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker KR, Nelson ME, Felson DT, Layne JE, Sarno R, Roubenoff R. The efficacy of home based progressive strength training in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol 2001;28: 1655-65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fransen M, Crosbie J, Edmonds J. Physical therapy is effective for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Rheumatol 2001;28: 156-64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKenna F, Borenstein D, Wendt H, Wallemark C, Lefkowith JB, Geis GS. Celecoxib versus diclofenac in the management of osteoarthritis of the knee. Scand J Rheumatol 2001;30: 11-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet 2001;357: 1191-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes R, Carr A. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of glucosamine sulphate as an analgesic in osteoarthritis of the knee. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41: 279-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cibere J, Esdaile JM, Thorne A, Singer J, Kopec JA, Canvin J, et al. Multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled glucosamine discontinuation trial in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2002;9(suppl): S1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rindone JP, Hiller D, Collacott E, Nordhaugen N, Arriola G. Randomized, controlled trial of glucosamine for treating osteoarthritis of the knee [see comments]. West J Med 2000;172: 91-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.