Couples present at a surgery or clinic because they have not conceived as quickly as they had expected. Some are concerned there may be serious problem that will stop them having a family. Subfertility investigations determine whether a problem exists and enable a rational discussion about options for treatment. The treatment may include waiting for a spontaneous conception. Some of the distress associated with subfertility may be reduced by a prompt and systematic protocol of investigations that allows couples to move quickly to the most appropriate treatment.

Figure 1.

Couple consulting doctor

Investigations: who and when

Subfertility is defined as failure to conceive after one year of unprotected regular sexual intercourse. Although usually it would be reasonable to start investigations after this time, earlier investigations and referral may be justified where there are important factors in either partner's history.,

Table 1.

| Female |

|---|

|

| Male |

|

Before a year

A woman's age is one of the main factors affecting her chance of conception. The chances of most treatments being successful are reduced substantially after a woman reaches 35 years and become negligible by her mid-40s. Hence, if couples are to gain the maximum benefit from the most appropriate treatment, investigations should be started promptly (after six months of trying if the woman is over 35) and completed according to a locally agreed protocol between general practitioners and hospital providers. Couples can then be counselled about the implications of test results, and a management plan agreed that takes into account the test results and the couple's beliefs and wishes.

At initial presentation both partners should have a history taken and be examined. Regular intercourse two to three times a week should be advised, but basal body temperature charts are not helpful and should be avoided.

The female partner of couples presenting with subfertility should have their rubella status checked so that if immunisation is required it will not delay any treatment

A rational approach to investigation

Initial investigations should be completed within three to four months and should establish the following points.

Does the woman ovulate?

If not, then why not?

Is the semen quality normal?

Is there tubal damage or uterine abnormality? Both partners must be investigated because an appropriate plan of management cannot be formulated without considering both male and female factors that may occur concurrently. Initial investigations can be started in the community, with the assessment of tubal patency taking place in hospital

Table 2.

| Female |

|---|

|

| Male |

|

Starting investigations in primary care

Does the woman ovulate and if not why not?

The UK Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists' guidelines include checking a mid-luteal phase progesterone to confirm ovulation in a regular cycle. Time the sample at the correct phase of the cycle (seven days before expected menses). Where cycles are irregular or the woman has oligomenorrhoea (a cycle length of > 35 days) or polymenorrhoea (< 25 days), ovulation is unlikely and so a progesterone test is of little value. Thyroid stimulating hormone, testosterone, and prolactin concentrations need be checked only if cycles are irregular or absent, suggesting anovulation, galactorrhoea, or symptoms of thyroid disorder. Transvaginal ultrasonography is a simple investigation that will detect polycystic ovaries and uterine fibroids. Luteinising hormone, FSH, and estradiol should be checked early in the cycle (days 2 to 6).

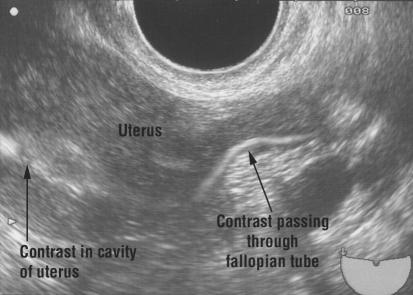

Figure 2.

HyCoSy showing patency and flow through one cornu of the uterus

Is semen quality normal?

The male partner should have a semen analysis and if some parameters are abnormal, then a second test should be done six weeks later. Ideally the samples should be analysed in the laboratory used by the fertility clinic to which the couple will be referred. More detailed sperm function tests are not needed as a routine part of the initial investigations. The postcoital test is unreliable and is no longer recommended as a routine investigation.

Table 3.

| Female |

|---|

| Assess tubal status and uterine cavity |

|

| Male |

| If azoospermia is present |

|

| If oligozoospermia and signs of hypogonadotrophic hypgonadism |

|

Investigations started in primary care should be completed in a dedicated reproductive medicine or fertility clinic.

Investigations in secondary care

Is there tubal damage or uterine abnormality?

Assessment of a woman's tubal status and uterine cavity can be performed by

Hysterosalpingography (HSG)

Hysterosalpingo-contrast sonography (HyCoSy)

Laparoscopy and dye test with hysteroscopy.

Tests for tubal patency should take place in the first 10 days of a cycle to avoid the possibility, however unlikely, of disrupting an early spontaneous pregnancy. Unless cervical screening for chlamydia has been performed, prophylactic antibiotics such as doxycycline and metronidazole should be given to minimise the risk of infection developing after the procedure.

HSG and HyCoSy

Figure 3.

Hysterosalpingogram showing a normal pelvis

HSG and HyCoSy are “dynamic” outpatient investigations done by inserting a catheter into the cervical canal, after which contrast is injected into the uterine cavity. HSG uses real time x ray imaging to follow the flow of contrast into the tubes and spill into the peritoneal cavity, whereas HyCoSy uses ultrasonography. Both give information about the shape of the uterine cavity. HyCoSy gives extra information because an ultrasound scan of the pelvis is performed at the same time, allowing the detection of fibroids or polycystic ovaries.

Laparoscopy and dye test

A laparoscopy and dye test needs general anaesthesia and carries the hazards of laparoscopy. However, it gives information about the degree of any tubal damage present and enables endometriosis to be detected. Additionally, laparoscopic treatment such as diathermy or laser ablation of endometriosis or salpingolysis or salpingostomy may be done at the same time. HyCoSy and HSG can be used as an initial screen, reserving laparoscopy for patients with a history or symptoms indicating a risk of tubal damage or endometriosis, and for those who have an abnormal HSG. If investigation of the male partner shows substantially impaired semen quality, such that assisted conception treatment (for example, intracytoplasmic sperm injection) is likely, tubal assessment may not be needed. However, information about the uterine cavity may be helpful if ultrasonography shows the presence of submucosal fibroids.

Figure 4.

Laparoscopy showing a normal pelvis with passage of blue dye through the fimbrial end of the left tube

Further investigation of azoospermia in secondary care

Where the initial semen analysis reveals azoospermia a centrifuged sample should be examined for sperm in the pellet. Even if only a few sperm can be identified, intracytoplasmic sperm injection can be offered as effective treatment to circumvent the infertility.

Table 4.

Investigating azoospermia, by site of abnormality

|

Obstructive

|

Non-obstructive

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-testicular | Testicular | Hypothalamic-pituitary | |

| Congenital causes | Vasal aplasia, cystic fibrosis, mullerian cysts | Genetic causes, cryptorchidism, anorchia | Kallman's syndrome, isolated FSH deficiency |

| Acquired causes | Gonorrhoea, chlamydia, tuberculosis, prostatitis, vasectomy | Radiotherapy, chemotherapy, orchitis, trauma, torsion | Craniopharyngioma, pituitary tumour, pituitary ablation, anabolic steroids |

| Testicular size | Normal | Small, atrophic | Small, prepubertal |

| FSH | Normal | Raised | Low |

| Testosterone | Normal | Low | Low |

If azoospermia is confirmed it is important to distinguish between obstructive and non-obstructive azoospermia.

In obstructive azoospermia, spermatogenesis is normal but there is a block in the epididymis or vas deferens. If congenital absence of vas deferens is suspected, both partners should undergo cystic fibrosis screening because many of these men will carry one of the cystic fibrosis mutations. In non-obstructive azoospermia, spermatogenesis is impaired. This impairment may be caused by testicular failure (so the man's karyotype should be checked and multiple testicular biopsy may show isolated foci of spermatogenesis) or due to a failure to stimulate spermatogenesis by the hypothalamic pituitary axis (hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism). Although rare, this condition should be detected as these patients respond to gonadotrophin treatment.

Interpreting results and discussing treatment options

Female partner

Where the progesterone concentration is low take the following steps.

Check the length of the cycle in which the sample was taken

Ensure that sample was taken in the mid-luteal phase—that is, seven days before expected period

Ensure that other endocrine tests are completed

An ultrasound scan is valuable to diagnose presence of polycystic ovaries if anovulation is confirmed or the luteinising hormone or testosterone concentrations, or both, are raised

Advise about weight gain or loss to achieve a body mass index (weight (kg)/(height (m)2)) of 20-30. This is the key to successful treatment.

Table 5.

Interpreting results of investigations of female partners

| Test | Result | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Progesterone | < 30 nmol/l | Anovulation: Check cycle length and timing in mid-luteal phase; complete other endocrine tests; scan for polycystic ovaries; advise on weight gain or loss; may need ovulation induction; clomifene should not be started without tubal patency test |

| FSH | > 10 IU/l | Reduced ovarian reserve: May respond poorly to ovulation induction; may need egg donation |

| Luteinising hormone | > 10 IU/l | May be polycystic ovaries: Ultrasonography to confirm |

| Testosterone | > 2.5 nmol/l | May be polycystic ovaries: Ultrasonography to confirm |

| > 5 nmol/l | Congenital adrenal hyperplasia: Check 17-OHP and DHEAS | |

| Prolactin | > 1000 IU/l | May be pituitary adenoma: Repeat prolactin to confirm raised concentration; exclude hypothyroidism; arrange magnetic resonance image or computed tomogram; if confirmed hyperprolactinaemia start dopamine agonist |

| Rubella | Non-immune | Offer immunisation and one month contraception |

| HSG or HyCoSy | Abnormal | May be tubal factor: Arrange laparoscopy and dye test to evaluate further; may be intrauterine abnormality—for example, fibroid or adhesions; evaluate further by hysteroscopy |

| Laparoscopy and dye | Blocked tubes | Tubal factor confirmed: Possibly suitable for transcervical cannulation, surgery or in vitro fertilisation (also depends on semen quality) |

| Endometriosis | Endometriosis: Assess severity; may benefit from diathermy or laser ablation; medical suppression not helpful for fertility May need in vitro fertilisation |

DHEAS = dihydroepiandrosterone sulphate;

17-OHP = 17-hydroxyprogesterone

A single raised early follicular phase follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) concentration is a poor prognostic indicator for women trying to conceive. It implies a reduced ovarian reserve and the possibility of incipient premature ovarian failure. This is difficult to treat because the response to ovarian stimulation is likely to be poor. Refractory cases may need egg donation.

After an abnormal hysterosalpinogram or HyCoSy, further tubal assessment by laparoscopy will be needed. The main treatment options include:

Surgery (open or laparoscopic)

Transcervical tubal cannulation

In vitro fertilisation.

The choice of procedure will depend on factors such as the degree of tubal damage, the semen quality, and the patient's age. Intrauterine lesions such as submucous fibroids or adhesions need further evaluation by hysteroscopy, at which time they may be resected.

Male partner

Semen samples can vary greatly. If the semen volume is low, check whether collection of the ejaculate was complete. If the first part of the ejaculate, which contains most of the sperm, missed the pot, the results will not be representative.

Lubricants for masturbation—for example, soap or KY jelly may be spermicidal and their use should be avoided. If the male partner has difficulty producing a sample by masturbation then a non-spermicidal condom can be used.

Table 6.

Interpreting a semen analysis

| Parameter | Normal | Comments if abnormal |

|---|---|---|

| Volume | 2-5 ml | If low, check if collection was incomplete (“missed the pot”) |

| Count | > 20 × 106/ml | Repeat sample. Check that no acute illness occurred in two months before sample. Lifestyle advice on smoking, alcohol, and drugs. If < 10 × 106/ml in vitro fertilisation or intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Refer early |

| Motility | > 50% progressively motile | Repeat sample; refer early |

| > 25% rapidly progressive | ||

| Morphology | > 15% normal shape | Repeat sample; refer early |

Therapeutic drugs that may be associated with impaired spermatogenesis include chemotherapy, sulfasalazine, and cimetidine.

Abnormal semen qualities are an indication for early referral to a fertility clinic, preferably one offering a full range of assisted conception techniques.

Conclusion

Couples who present with subfertility rarely have absolute infertility (that is, no chance of conception spontaneously). Factors that are contributing to the problem usually cause relative subfertility (that is, a reduced chance of conceiving spontaneously) to a greater or lesser degree, and there may be relevant factors in both partners.

Investigations should follow a systematic protocol designed to identify:

Tubal or uterine abnormalities

Anovulation

Impaired spermatogenesis.

Prompt investigation and appropriate referral allow a couple to receive advice and treatment to help them reach their goal of a pregnancy more quickly, and may alleviate some of the distress associated with subfertility. Doctors in primary care can have an invaluable role in starting this process and providing support during further investigation and treatment.

The ABC of subfertility is edited by Peter Braude, professor and head of department of women's health, Guy's, King's, and St Thomas's School of Medicine, London, and Alison Taylor, consultant in reproductive medicine and director of the Guy's and St Thomas's assisted conception unit.. The series will be published as a book in the winter.

Competing interests: None declared.

Further reading and resources

- • Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists evidence based clinical guidelines. Initial investigation and management of the subfertile couple. London: RCOG Press, 1998

- • Templeton A, Ashok P, Bhattacharya S, Gazvani R, Hamilton M, MacMillan S, et al. Evidence based fertility treatment London: RCOG Press, London, 2000

- • Balen A, Jacobs H. Infertility in practice. 2nd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2003

- • Templeton A, Ashok P, Bhattacharya S, Gazuani R, Hamilton M, MacMillan S, et al. Management of infertility for the MRCOG and beyond. London: RCOG Press, 2000