Abstract

Aim

Several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of the cytochrome P450 enzyme 1A2 gene (CYP1A2) have been reported. Here, frequencies, linkage disequilibrium and phenotypic consequences of six SNPs are described.

Methods

From genomic DNA, 114 British Caucasians (49 colorectal cancer cases and 65 controls) were genotyped for the CYP1A2 polymorphisms −3858G→A (allele CYP1A2*1C), −2464T→delT (CYP1A2*1D), −740T→G (CYP1A2*1E and *1G), −164A→C (CYP1A2*1F), 63C→G (CYP1A2*2), and 1545T→C (alleles CYP1A2*1B, *1G, *1H and *3), using polymerase chain reaction–restriction fragment length polymorphism assays. All patients and controls were phenotyped for CYP1A2 by h.p.l.c. analysis of urinary caffeine metabolites.

Results

In 114 samples, the most frequent CYP1A2 SNPs were 1545T→C (38.2% of tested chromosomes), −164A→C (CYP1A2*1F, 33.3%) and −2464T→delT (CYP1A2*1D, 4.82%). The SNPs were in linkage disequilibrium: the most frequent constellations were found to be −3858G/−2464T/−740T/−164A/63C/1545T (61.8%), −3858G/−2464T/−740T/−164C/63C/1545C (33.3%), and −3858G/−2464delT/−740T/−164A/63C/1545C (3.51%), with no significant frequency differences between cases and controls. In the phenotype analysis, lower caffeine metabolic ratios were detected in cases than in controls. This was significant in smokers (n = 14, P = 0.020), and in a subgroup of 15 matched case-control pairs (P = 0.007), but it was not significant in nonsmokers (n = 100, P = 0.39). There was no detectable association between CYP1A2 genotype and caffeine phenotype.

Conclusions

(i) CYP1A2 polymorphisms are in linkage disequilibrium. Therefore, only −164A→C (CYP1A2*1F) and −2464T→delT (CYP1A2*1D) need to be analysed in the routine assessment of CYP1A2 genotype; (ii) in vivo CYP1A2 activity is lower in colorectal cancer patients than in controls, and (iii) CYP1A2 genotype had no effect on phenotype (based on the caffeine metabolite ratio). However, this remains to be confirmed in a larger study.

Keywords: caffeine test, CYP1A2, cytochrome P450 1A2, gene polymorphism

Introduction

The cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP1A2 is one of the drug-metabolizing enzymes of major importance as it catalyses the phase I metabolism of a broad range of different drugs including clozapine, olanzapine, and tacrine [1–3]. Its contribution to caffeine metabolism is well-documented and is the basis of the caffeine phenotyping test, used to assess an individual's CYP1A2 metabolic activity [4–6].

Moreover, CYP1A2 is one of the enzymes responsible for the activation of aromatic and heterocyclic amines (HAs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) [7, 8]. Such compounds are formed during the frying or broiling of meat, and their metabolism via CYP1A2 results in the formation of reactive metabolites that can bind to DNA to give adducts that have the potential to cause mutations and eventually lead to cancer. Therefore, high in vivo CYP1A2 activity has been suggested to be a susceptibility factor for cancers of the bladder, colon and rectum [9, 10] where exposure to compounds such as aromatic amines and HAs has been implicated in the aetiology of the disease. This makes CYP1A2 a key target enzyme for epidemiological studies on diet-related cancers such as colorectal cancer.

In vivo, CYP1A2 activity exhibits a significant degree of interindividual variation. One possible explanation for this is that CYP1A2 expression is highly inducible by a number of dietary and environmental chemicals including tobacco smoking [11], which is mediated via ligand binding at the Ah receptor [12]. Another possible contributor to interindividual variability in CYP1A2 activity is the occurrence of polymorphisms in the CYP1A2 gene. In the past few years, a number of CYP1A2 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been reported [13–20], four of which lie in the 5′-noncoding promoter region. The current nomenclature (as of 2 July 2002) proposed by the International CYP Allele Nomenclature Committee is given in Table 1[20]. One of the known CYP1A2 SNPs, CYP1A2 3858G→A (CYP1A2*1C), has been reported to cause decreased enzyme activity in smokers [17] but seems to be rare. Another SNP, the very common CYP1A2 164A→C polymorphism (CYP1A2*1F), has also been associated with reduced activity in smokers [14, 15, 18] and may contribute significantly to the substantial interindividual variation in CYP1A2 activity. Relatively little is known about other CYP1A2 SNPs in terms of their allele frequency, possible linkage disequilibrium and functional consequences.

Table 1.

Current CYP1A2 allele nomenclature [20] (as of 2 July 2002).

| Allele | Nucleotide changes | Protein sequence changes |

|---|---|---|

| CYP1A2*1 A | None | None |

| CYP1A2*1B | 1545T→C | None |

| CYP1A2*1C | −3858G→A | None |

| CYP1A2*1D | −2464T→delT | None |

| CYP1A2*1E | −740T→G | None |

| CYP1A2*1F | −164A→C | None |

| CYP1A2*1G | −740T→G, 1545T→C | None |

| CYP1A2*1H | 951A→C, 1545T→C | None |

| CYP1A2*2 | 63C→G | F21L |

| CYP1A2*3 | 1042G→A, 1545T→C | D348N |

| CYP1A2*4 | 1156A→T | I386F |

| CYP1A2*5 | 1217G→A | C406Y |

| CYP1A2*6 | 1291C→T | R431W |

In this study, we report allele frequencies and linkage disequilibrium for six known CYP1A2 polymorphisms. Furthermore, we investigated whether CYP1A2 genotype correlates with caffeine phenotype and if there were any differences in CYP1A2 caffeine phenotype (ie CYP1A2 activity) between colorectal cancer patients and controls. This work was performed as part of a larger study on the influence of polymorphisms in enzymes metabolizing heterocyclic amines on the risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Subjects and methods

Patients and controls

Our study population consisted of 114 individuals, 49 colorectal cancer patients and 65 controls without cancer, from York, UK, recruited in a multicentre case-control study performed between August 1997 and February 2001 at the Universities of Dundee, Leeds and York. Patients had incident colorectal cancer (ICD-9 classification 153) with confirmed pathology reports. Patients as well as controls without cancer were 45–80 years old, of Caucasian origin, and had no previous other malignant diseases. Patients comprised 44 nonsmokers plus five current smokers, whilst controls comprised 56 nonsmokers plus nine current smokers. As a subgroup, there were 15 nonsmoking case-control pairs who were matched for age, sex and general practitioner. The Tayside Committee on Medical Research Ethics, the York Research Ethics Committee and the Leeds Health Authority/St James's & Seacroft University Hospitals Local Research Ethics Committee approved the study, and each participating individual gave written informed consent for both phenotyping and genotyping analysis, which were performed blind to the identity of the subject group.

Phenotyping procedure

Subjects were asked to refrain from the consumption of caffeine-containing foods and beverages and paracetamol (to avoid assay interference) for 24 h prior to the test. A cup of instant coffee (4 g) was drunk and urine collected for 8 h. The latter were extracted and analysed by high-performance liquid chromatography (h.p.l.c.) [4]. The caffeine metabolite ratio (MR) [(AAMU + AFMU + 1 U + 1X)/17 U] was used as an index of CYP1A2 activity (modified from Campbell et al.[21]). Lower limits of quantification were 0.25 (AFMU, 1 U, 17 U) to 0.5 (AAMU, 1X) µg ml−1 urine. Interassay variance for the MR was 7.6%.

Genotype analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from 200 µl of EDTA blood, using a QIAamp 96-spin blood kit (Qiagen Ltd., Crawley, UK). DNA was stored at −20°C prior to analysis. Genotesting for six CYP1A2 polymorphic sites (−3858G→A, −2464T→delT, −740T→G, −164 A→C, 63C→G, 1545T→C) was carried out adapting polymerase chain reaction–restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP) assays reported in the literature; a compilation of assay conditions is given in Table 2. All PCR reactions were run on a 10-µl scale, with each mastermix comprising 0.2 mm dNTPs, 200 nm of each of the primers, 1 U of Taq polymerase, the appropriate concentration of MgCl2 (see Table 2) and PCR buffer, all purchased from Promega (Southampton, UK).

Table 2.

Primers and PCR conditions used for CYP1A2 genotyping.

| SNP | PrimerName | Sequence (5′→3′) | PCR program | Mg2+concentration | Bandsize | Restrictionenzyme | Incubationtemperature | Bandpatterns | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −3858G→A | R2 | GCTACACATGATCGAGCTATAC | 35x (30 s 94°C– | 1.75 mm | 568 bp | BslI | 55°C | G: 343-132-93 | [17] |

| R3 | CAGGTCTCTTCACTGTAAAGTTA | 10 s 52°C−1min 72°C) | A: 475–93 | ||||||

| −2464delT | dTF | TGAGCCATGATTGTGGCATA | 35x (30 s 94°C– | 1.25 mm | 167 bp | NdeI | 37 °C | T: 167 | [15] |

| dTR | AGGAGTCTTTAATATGGACCCAG | 10 s 49°C−1min 72°C) | delT: 148–19 | ||||||

| −740T → G | 740F | CACTCACCTAGAGCCAGAAGCTC | 35x (30 s 94°C– | 1.25 mm | 239 bp | HaeIII | 37 °C | T: 205–34 | [15] |

| 740R | AGAGCTGGGTAGCAAAGCCTGGA | 10 s 49°C−1min 72°C) | G: 175-34-30 | ||||||

| −164 A → C | 11F | TGAGGCTCCTTTCCAGCTCTCA | 35x (30 s 94°C– | 1.25 mm | 265 bp | Bsp120I | 37 °C | A: 265 | [18] |

| 4R | AGAAGCTCTGTGGCCGAGAAGG | 10 s 58°C−1min 72°C) | C: 211–54 | ||||||

| 63C→G | chF | ATGAATGAATGAATGTCTC | 40x (30 s 94°C– | 1.75 mm | 201 bp | MboII | 37 °C | C: 122–79 | [16] |

| chR | CTCTGGTGGACTTTTCAG | 10 s 49°C−40 s 72°C) | G: 201 | ||||||

| 1545T→C | F01 | AGCCCTTGAGTGAGAAGATG | 35x (30 s 94°C– | 1.75 mm | 479 bp | Tsp509I | 65 °C | T: 218-175-52-34 | [13] |

| R01 | GGTCTTGCTCTGTCACTCA | 10 s 58°C−1min 72°C) | (2 h) | C: 393-52-34 |

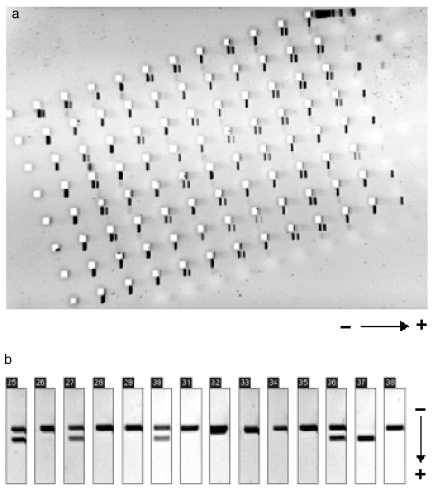

Analysis of restriction fragment patterns was performed on 96-well MADGE gels (Madgebio Ltd, Huntington, UK). This system is based on microtitre plate-sized 10% polyacrylamide gels, allowing a cost-efficient and time-saving high-throughput simultaneous analysis of 96 samples. Results were documented using a digital gel-analysis system and Phoretix Advanced software (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

MADGE gel PCR-RFLP genotyping. (a) On one microtitre plate-sized polyacrylamide gel, 94 samples were typed for −164A→C (CYP1A2*1F) with restriction enzyme Bsp120I. (b) Example of MADGE data output format (lanes 25–38 from the gel seen above).

Data analysis

Analysis of possible linkage disequilibrium between six CYP1A2 SNPs was performed using the computer program EH/EH Plus [22, 23], which calculates maximum likelihood estimates of the frequencies of each possible haplotype.

Possible differences in SNP or allele frequencies between cases and controls were tested by two-sided Fisher's exact test. For genotype- and case–control-stratified comparison of caffeine phenotype, the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney tests were applied (Stata 7.0 software; Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA), taking into consideration that the caffeine metabolic ratios were not normally distributed in all subgroups as determined by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Metabolic ratios between matched case/control pairs were compared using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Results

A total of 114 study participants (49 colorectal cancer patients and 65 healthy controls) were genotyped for the CYP1A2 polymorphisms −3858G→A (allele CYP1A2*1C), −2464T→delT (CYP1A2*1D), −740T→G (CYP1A2*1E and *1G), −164 A→C (CYP1A2*1F), 63C→G (CYP1A2*2), and 1545T→C (alleles CYP1A2*1B, *1G, *1H and *3) [20, 24, 25]. For the SNPs, there were no significant differences in frequencies between cases and controls as calculated by two-sided Fisher's exact test (see below, Table 3). Therefore, the allele frequencies in all 114 subjects were pooled and are shown in Figure 2. The most frequent SNPs were CYP1A2 1545T→C (alleles CYP1A2*1B, *1G, *1H and *3; overall frequency 38.2% of chromosomes, cases 36.7%, controls 39.2%), CYP1A2-164A→C (CYP1A2*1F; overall 33.3%, cases 32.7%, controls 33.8%) and CYP1A2-2464T→delT (CYP1A2*1D; overall 4.82%, cases 4.08%, controls 5.38%).

Table 3.

Comparison of CYP1A2 SNP and allele frequencies in 49 colorectal cancer cases and 65 controls.

| Cases | Controls | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP/allele | n | % | (95% CI) | n | % | (95% CI) | P-value* |

| SNPs | |||||||

| −3858G→A (CYP1A2*1C) | 1 | 1.02 | 0.00–6.15 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.00–4.67 | 1.00 |

| −2464T→delT (CYP1A2*1D) | 4 | 4.08 | 0.74–10.9 | 7 | 5.38 | 1.75–11.5 | 0.76 |

| −740T→G (CYP1A2*1E and *1G) | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00–4.21 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.00–4.67 | 1.00 |

| −164A→C (CYP1A2*1F) | 32 | 32.7 | 22.1–44.0 | 44 | 33.8 | 24.5–43.7 | 0.89 |

| 63C→G (CYP1A2*2) | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00–4.21 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00–3.19 | 1.00 |

| 1545T→C (CYP1A2*1B, *1G, *1H and *3) | 36 | 36.7 | 25.7–48.2 | 51 | 39.2 | 29.5–49.2 | 0.78 |

| Allelic constellations | |||||||

| −3858G −2464T −740T −164A 63C 1545T | 62 | 63.3 | 51.1–73.7 | 79 | 60.8 | 50.3–70.1 | 0.78 |

| −3858G −2464T −740T −164C 63C 1545C | 32 | 32.7 | 22.1–44.0 | 44 | 33.8 | 24.5–43.7 | 0.89 |

| −3858G −2464delT −740T −164A 63C 1545C | 3 | 3.06 | 0.34–9.39 | 5 | 3.85 | 0.92–9.37 | 1.00 |

| −3858A −2464delT −740T −164A 63C 1545C | 1 | 1.02 | 0.00–6.15 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.00–4.67 | 1.00 |

| −3858G −2464delT −740G −164A 63C 1545C | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00–4.21 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.00–4.67 | 1.00 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

P-values derived from two-sided Fisher's exact test.

Figure 2.

Frequency of different CYP1A2 SNPs in 114 subjects (49 colorectal cancer patients plus 65 controls). The localization of the respective sites within the gene is indicated (not scaled). 63C→G results in an amino acid alteration (F21L), 1545T→C is a silent polymorphism, whereas the other four sites are potential promoter polymorphisms. Allele frequencies are maximum likelihood haplotype frequencies as calculated by the EH linkage disequilibrium program.

The common CYP1A2 polymorphisms were found to be in linkage disequilibrium. The maximum likelihood estimates of haplotype frequencies were calculated using the EH linkage disequilibrium program [22, 23], and are shown in Figure 2. The most frequent allelic constellations were calculated to be −3858G/−2464T/−740T/−164A/63C/1545T (61.8%), −3858G/−2464T/−740T/−164C/63C/1545C (33.3%), and −3858G/−2464delT/−740T/−164A/63C/1545C (3.51%).

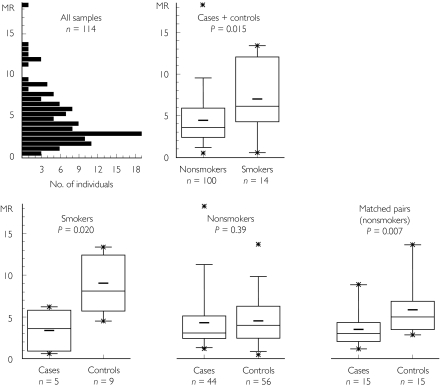

As expected, the 14 smokers (five cases plus nine controls) had significantly higher metabolic ratios (MR) than the 100 nonsmokers (44 cases plus 56 controls) (P = 0.015; Figure 3). Metabolic ratios were highly skewed, so to estimate the difference in MR between groups, they were log-transformed to form a more normally distributed variable. The geometric mean of the ratio of the MR in smokers compared with nonsmokers was 1.49, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01, 2.19. As illustrated in Figure 3, after stratifying cases and controls according to their smoking status, MRs were significantly lower in cases than in controls among the smokers (five cases vs. nine controls, P = 0.020, ratio of control MR to cases 3.45, 95% CI 1.51, 7.85), whereas this effect was not significant in nonsmokers (44 cases vs. 56 controls, P = 0.39, ratio 1.04, 0.80, 1.35). Analysis of the subgroup of 15 matched case-control pairs (all nonsmokers, matched for age, sex and general practitioner) gave a P-value of 0.007 in the paired analysis, with a mean ratio of controls to cases of 1.78 (95% CI 1.26, 2.51).

Figure 3.

The frequency distribution of caffeine metabolic ratios (MR) in all 114 subjects. Data are also stratified according to case/control and smoking status. Box plots show median, 1st and 3rd quartiles, mean (–) and minimum/maximum values (*), respectively. As expected, CYP1A2 activity was higher in smokers than in nonsmokers. Consistently, colorectal cancer cases had a lower activity than controls, in both smokers and nonsmokers, and also in the subgroup of 15 nonsmoking matched case-control pairs. No significant differences were observed by comparing caffeine metabolic ratios between different CYP1A2 genotypes (data not shown).

Possible correlations between CYP1A2 genotype and phenotype were investigated within the cancer and control groups and in the population as a whole. No significant association between caffeine phenotype and any SNP, allele or combination of alleles was found in the three groups or in the 14 smokers and 100 nonsmokers (data not shown).

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of six known CYP1A2 SNPs, their linkage disequilibrium and frequencies in British Caucasians. The frequency of the CYP1A2-164A→C polymorphism (CYP1A2*1F, 33.3%) was comparable to that found in an earlier study in German Caucasians (32.2%) [18]. In a recent report, CYP1A2 1545T→C (CYP1A2*1B, *1G, *1H and *3) was found to be present in 70 of 200 French Caucasian chromosomes (35.0%) [26], which compares well with the CYP1A2-1545T→C frequency of 38.2% found in the present study. Polymorphisms CYP1A2-2464T→delT (CYP1A2*1D) and CYP1A2 740T→G (CYP1A2*1E and *1G) were significantly less frequent in our 114 Caucasians (frequency 4.82% and 0.44% of chromosomes, respectively) than in 159 Japanese individuals (42.0% and 8.20%) [15]. However, ethnic differences in SNP frequency are not uncommon. Information about the population frequencies of the other SNPs in Caucasians was not available. Therefore, the study presented here describes the first comprehensive analysis of these CYP1A2 SNPs in Caucasians.

The common CYP1A2 polymorphisms were found to be in linkage disequilibrium. Before this study, most CYP1A2 SNPs had been analysed independently. However, the extent of linkage disequilibrium observed in the present study suggests that a change in the current nomenclature of CYP1A2 alleles [20] might be appropriate. Some of the SNPs defining alleles in the current system seem not to occur on their own, but together with other SNPs. However, this might only be true in British Caucasians, as the linkage disequilibrium is based on frequencies observed in the one ethnic group tested here. Therefore, SNP frequencies and their linkage disequilibrium may be different in other ethnic groups.

CYP1A2 1545T→C was always in linkage disequilibrium to either CYP1A2-164A→C (CYP1A2*1F) or CYP1A2-2464T→delT (CYP1A2*1D). The CYP1A2-63C→G (CYP1A2*2) genotype was not found in any of our 114 British Caucasians, whereas CYP1A2-740T→G (CYP1A2*1E and*1G) was found in only one heterozygous individual. Thus, these three sites (1545T→C, 63C→G, −740T→G) do not have to be screened when populations are being routinely genotyped. Furthermore, the CYP1A2-3858G→A polymorphism (CYP1A2*1C) was not very frequent in our population. In the two cases we detected in 114 individuals, it was found to occur in combination with CYP1A2-2464T→delT, indicating that routine screening for CYP1A2-3858G→A is useful only in samples that are positive for CYP1A2-2464T→delT. Hence, in a sample of colorectal cancer cases and controls (total n = 1099), we subsequently screened for CYP1A2-3858G→A only in CYP1A2-2464T→delT-positive samples. Twenty samples out of 1099 were positive for CYP1A2-3858G→A (unpublished data), giving almost the same frequency as the two out of 114 individuals identified in the present study (0.88% vs. 0.91%).

Recently, three additional novel CYP1A2 SNPs have been published [27]. The first, CYP1A2-3591T→G, had a frequency of 1.72% in 174 Caucasians (ie in 348 chromosomes), and appeared to have little effect on CYP1A2 promoter activity. For two others, CYP1A2 3595G→T and CYP1A2-3605insT, the population frequency in Caucasians was small and the functional consequences of the polymorphism were negligible. However, all three SNPs seemed to be more frequent in African-Americans and Taiwanese than in Caucasians [27].

Five additional SNPs were reported by Chevalier et al.[26], namely 951A→C (CYP1A2*1H), 1042G→A (CYP1A2*3), 1156A→T (CYP1A2*4), 1217G→A (CYP1A2*5) and 1291C→T (CYP1A2*6) (see Table 1). As only two heterozygotes (for 1042G→A) and one heterozygote (for the other four SNPs, respectively) were detected in 100 French Caucasians, these variants appeared to be relatively rare. Therefore, we are convinced that these additional SNPs can be excluded, at least in Caucasians, as significant determinants of interindividual variability in CYP1A2 activity. However, frequencies of these SNPs in subjects of other ethnic extraction might be higher.

In conclusion, routine genotyping for variants CYP1A2-164A→C (CYP1A2*1F) and CYP1A2-2464T→delT (CYP1A2*1D) would appear to be sufficient to detect most CYP1A2 genotypes in Caucasians, as the frequency of each of the other known CYP1A2 SNPs is less than 2%.

As expected from previous work, a significantly higher CYP1A2 activity (based on the caffeine metabolite ratio) was observed in the 14 smokers compared with the 100 nonsmokers in our population. Unexpectedly, colorectal cancer cases showed a lower CYP1A2 activity than controls. Whereas the effect did not reach a significant level in nonsmokers, the difference was significant in smokers, and was striking in 15 matched nonsmoker case–control pairs. This finding cannot be explained by a divergent distribution of genotypes in the cases and controls, as there was no significant difference in genotype frequencies between the two groups. Surprisingly, the shift was in the direction we did not expect, namely towards lower activity in patients. The prevailing hypothesis is that subjects with increased susceptibility to colon cancer have higher CYP1A2 activity, and greater activation of pro-carcinogenic compounds, than noncancer subjects. This is apparently supported by the results of Lang et al.[9] in colorectal cancer patients, as well as those from Spigelman et al.[28] in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) patients. In both studies, patients had higher CYP1A2 activity using caffeine as a probe than controls, although the difference was only slight in the investigation by Lang et al.[9]. In contrast, we observed the opposite effect, and whereas this may be in part due to our relatively small study population, the consistency of the shift in activity in the three subgroups (smokers, nonsmokers, matched case–control pairs, Figure 3) strongly points against a chance finding. However, there are fundamental differences between the patient cohorts of Lang et al.[9], Spigelman et al.[28] and ours. All of our patients had a confirmed diagnosis of colorectal cancer (Dukes stage A, B or C), whereas only 45% of patients in the Lang et al.[9] study had colorectal cancer, the remainder being diagnosed with polyps. In the Spigelman et al.[28] report, the study population were FAP patients, whereas in our study a diagnosis of FAP was an exclusion criterion. One possible explanation might be that advanced cancer may go together with impaired liver function. Another possible explanation might be differences in diet between cancer patients and healthy controls. It is well established that certain vegetables can decrease CYP1A2 activity, whereas meat has the opposite effect [29, 30]. It is possible that cancer patients may modify their eating habits in a ‘healthier’ direction, and that consumption of a relatively fruit and vegetable-rich diet compared with the ‘normal’ western diet of the healthy controls, which is rich in grilled meat, might cause a decrease in CYP1A2 activity.

Among the 100 nonsmokers, no significant differences in CYP1A2 activity were observed when stratified for CYP1A2 genotype. It is known that CYP1A2-164A→C (CYP1A2*1F) influences caffeine metabolic activity [18]. Thus, significantly higher activity was observed in carriers of the CYP1A2-164A/A constellation, but only in a study group of smokers. It has been speculated that this might be due to modification of a hypothetical binding motif in intron 1, which then facilitates higher CYP1A2 induction by tobacco smoke components [14, 18]. However, the group of smokers in the present investigation was small, so that the power to see any genotype-dependent shift in activity was low. There was no effect in nonsmokers, which agrees with the previous reports in which no genotype-dependent shift in activity could be detected in such subjects. Presumably, the CYP1A2 promoter polymorphisms are relevant only in smokers, where they can influence enzyme activity by affecting the mechanism of gene induction. Further investigations on CYP1A2 genotype and phenotype in a larger sample of smokers will be required before any definitive conclusion can be reached.

Owing to their low population frequency, nothing can be concluded about the functional influence of the CYP1A2-3858G→A (CYP1A2*1C, two out of 228 chromosomes) and the CYP1A2-740T→G (CYP1A2*E and *1G, one out of 228 chromosomes) polymorphisms, although the metabolic ratios of these subjects (MR 0.6, 13.4 and 4.3, respectively) did not show a trend in any particular direction. Nakajima et al.[17] described the CYP1A2-3858G→A variant (CYP1A2*1C) as expressing low activity enzyme, which would explain the one subject with a MR of 0.6. However, this is not consistent with the other CYP1A2-3858G→A (CYP1A2*1C) carrier who was a very fast metabolizer with a MR of 13.4. Again, a larger sample of smokers will be needed to resolve these questions.

In conclusion, as CYP1A2 polymorphisms are in strong linkage disequilibrium, only two sites (−164A→C (CYP1A2*1F) and −2464T→delT (CYP1A2*1D)) need to be typed routinely to allow assessment of CYP1A2 genotype. In contrast to previous studies, the in vivo activity of CYP1A2 in our study was lower in colorectal cancer patients than in controls. CYP1A2 genotype does not appear to explain interindividual variation in CYP1A2 metabolic activity in nonsmokers, and further investigations in a larger sample of smokers are needed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Food Standards Agency (FSA), grants T01003, T01004 and T01005. We wish to acknowledge the contribution of the research nurses Lillian Lund and Trish Morley in recruiting the York-based study participants.

References

- 1.Bertz RJ, Granneman GR. Use of in vitro data and in vivo data to estimate the likelihood of metabolic pharmacokinetic interactions. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32:210–258. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199732030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Compilation of CYP1A2 Substrates. Available at: http://www.georgetown.edu/departments/pharmacology/davetab.html.

- 3.Gentest Database of CYP1A2 Substrates. Available at: http://www.gentest.com/human_p450_database.

- 4.Butler MA, Iwasaki M, Guengerich FP, Kadlubar FF. Human cytochrome P-450PA (P-450IA2), the phenacetin O-deethylase, is primarily responsible for the hepatic 3-demethylation of caffeine and N-oxidation of carcinogenic arylamines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7696–7700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalow W, Tang BK. Use of caffeine metabolite ratios to explore CYP1A2 and xanthine oxidase activities. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1991;50:508–519. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1991.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler MA, Lang NP, Young JF, et al. Determination of CYP1A2 and NAT2 phenotypes in human populations by analysis of caffeine urinary metabolites. Pharmacogenetics. 1992;2:116–127. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199206000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boobis AR, Lynch AM, Murray S, et al. CYP1A2-catalyzed conversion of dietary heterocyclic amines to their proximate carcinogens is their major route of metabolism in humans. Cancer Res. 1994;54:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gooderham NJ, Murray S, Lynch AM, et al. Heterocyclic amines: evaluation of their role in diet associated human cancer. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;42:91–98. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1996.37513.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang NP, Butler MA, Massengill J, et al. Rapid metabolic phenotypes for acetyltransferase and cytochrome P4501A2 and putative exposure to food-borne heterocyclic amines increase the risk for colorectal cancer or polyps. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:675–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daly AK, Cholerton S, Armstrong M, Idle JR. Genotyping for polymorphisms in xenobiotic metabolism as a predictor of disease susceptibility. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102(Suppl 9):55–61. doi: 10.1289/ehp.94102s955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalow W, Tang BK. Caffeine as a metabolic probe: exploration of the enzyme-inducing effect of cigarette smoking. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1991;49:44–48. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1991.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quattrochi LC, Vu T, Tukey RH. The human CYP1A2 gene and induction by 3-methylcholanthrene. A region of DNA that supports AH-receptor binding and promoter-specific induction. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6949–6954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakajima M, Yokoi T, Mizutani M, Shin S, Kadlubar FF, Kamataki T. Phenotyping of CYP1A2 in Japanese population by analysis of caffeine urinary metabolites: absence of mutation prescribing the phenotype in the CYP1A2 gene. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:413–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacLeod SL, Tang Y-M, Yokoi T, et al. The role of recently discovered genetic polymorphism in the regulation of the human CYP1A2 gene. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 1998;39:396. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chida M, Yokoi T, Fukui T, Kinoshita M, Yokota J, Kamataki T. Detection of three genetic polymorphisms in the 5′-flanking region and intron 1 of human CYP1A2 in the Japanese population. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1999;90:899–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1999.tb00832.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang JD, Guo WC, Lai MD, Guo YL, Lambert GH. Detection of a novel cytochrome P-450 1A2 polymorphism (F21L) in Chinese. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakajima M, Yokoi T, Mizutani M, Kinoshita M, Funayama M, Kamataki T. Genetic polymorphism in the 5′-flanking region of human CYP1A2 gene: effect on the CYP1A2 inducibility in humans. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1999;125:803–808. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sachse C, Brockmöller J, Bauer S, Roots I. Functional significance of a C→A polymorphism in intron 1 of the cytochrome P450 1A2 (CYP1A2) gene tested with caffeine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;47:445–449. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welfare MR, Aitkin M, Bassendine MF, Daly AK. Detailed modelling of caffeine metabolism and examination of the CYP1A2 gene: lack of a polymorphism in CYP1A2 in Caucasians. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:367–375. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199906000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. [2 July 2002];Current Up-to-Date CYP1A2 Allele Nomenclature. Available at: http://www.imm.ki.se/CYPalleles/cyp1a2.htm.

- 21.Campbell ME, Spielberg SP, Kalow W. A urinary metabolite ratio that reflects systemic caffeine clearance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1987;42:157–165. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1987.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie X, Ott J. Testing linkage disequilibrium between a disease gene and marker loci. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:1107. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao JH, Curtis D, Sham PC. Model-free analysis and permutation test for allelic associations. Hum Hered. 2000;50:133–139. doi: 10.1159/000022901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ingelman-Sundberg M, Daly AK, Nebert D, Oscarson M. Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Nomenclature Committee. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200002000-00012. Available at: http://www.imm.ki.se/CYPalleles. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Daly AK, Brockmöller J, Broly F, et al. Nomenclature for human CYP2D6 alleles. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:193–201. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199606000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chevalier D, Cauffiez C, Allorge D, et al. Five novel natural allelic variants -951A→C, 1042G→A (D348N), 1156A→T (I386F), 1217G→A (C406Y) and 1291C→T (C431Y) of the human CYP1A2 gene in a French Caucasian population. Hum Mutat. 2001;17:355–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aitchison KJ, Gonzalez FJ, Quattrochi LC, et al. Identification of novel polymorphisms in the 5′ flanking region of CYP1A2, characterization of interethnic variability, and investigation of their functional significance. Pharmacogenetics. 2000;10:695–704. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spigelman AD, Farmer KC, Oliver S, et al. Caffeine phenotyping of cytochrome P4501A2, N-acetyltransferase, and xanthine oxidase in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 1995;36:251–254. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacLeod S, Sinha R, Kadlubar FF, Lang NP. Polymorphisms of CYP1A1 and GSTM1 influence the in vivo function of CYP1A2. Mutat Res. 1997;376:135–142. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(97)00036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lampe JW, King IB, Li S, et al. Brassica vegetables increase and apiaceous vegetables decrease cytochrome P450 1A2 activity in humans: changes in caffeine metabolite ratios in response to controlled vegetable diets. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1157–1162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]