Abstract

Aims

To evaluate the effect of a 3-day regimen of ibuprofen 600 mg × 4 on acute postoperative swelling and pain and other inflammatory events after third molar surgery compared with a traditional regimen of paracetamol 1000 mg × 4.

Methods

A controlled, randomized, double-blind, cross-over study where 36 patients (26 females, 10 males) with mean age 23 (range 19–27) years acted as their own controls. All patients were subjected to surgical removal of bilateral third molars. After one operation the patients received tablets of ibuprofen 600 mg × 4 for 3 days. After the other operation they received an identical regimen of paracetamol 1000 mg tablets. Swelling was objectively measured (mm) with a standardized face bow and the patients scored their pain intensity (PI) on a 100-mm visual analogue scale.

Results

There was no statistically significant difference between paracetamol and ibuprofen treatment with respect to effect on acute postoperative swelling. Swelling after paracetamol on the third postoperative day was 1.8% less than that after ibuprofen. Mean (95% CI) difference between treatments was −0.3 (−4.7, 4.1) mm. On the sixth postoperative day swelling after ibuprofen was 2.3% less than that after paracetamol. Mean (95% CI) between treatments was 0.2 (−2.4, 2.8) mm. There was no statistically significant difference in pain intensity between the paracetamol and the ibuprofen regimen on the day of surgery. The mean (95% CI) difference between the treatments for summed pain intensity on the day of surgery (SUMPI3.5−11) was 3.31 (−47.7, 54.3) mm. Two patients developed fibrinolysis of the blood clot (dry socket) after receiving ibuprofen while none did this after paracetamol treatment. There was no noticeable difference between treatments with respect to appearance of haematomas/ecchymoses or adverse effects which all were classified as mild to moderate.

Conclusions

A 3-day regimen of ibuprofen 600 mg × 4 daily does not offer any clinical advantages compared with a traditional paracetamol regimen 1000 mg × 4 daily with respect to alleviation of acute postoperative swelling and pain after third molar surgery.

Keywords: drug regimen, ibuprofen, pain, paracetamol, randomized trial, swelling, third molar surgery

Introduction

Paracetamol (acetaminophen, 4′-hydroxyacetanilide) is traditionally characterized by textbooks as an antipyretic and analgesic drug. Racemic ibuprofen [(RS)-2-(4-isobutylphenyl)-propionic acid] is a propionic acid drug that has gained a reputation as an over-the-counter alternative to paracetamol for analgesia in acute postoperative dental pain, due to its claimed analgesic superiority over paracetamol based on meta-analyses [1, 2] and clinical single-dose studies [3–6].

Little or no anti-inflammatory (e.g. ability to reduce swelling) activity is commonly ascribed to paracetamol in textbooks [7], but paracetamol 1000 mg regimens actually reduce objectively measured acute postoperative swelling after third molar surgery by 30% [8, 9], while ibuprofen 400 mg regimens only reduce acute postoperative swelling by 11% compared with placebo [10]. Voigt [11], who also used objective measurements, demonstrated that an ibuprofen 400 mg regimen did not reduce postoperative swelling following third molar surgery better than a paracetamol 1000 mg regimen.

The assumption that increasing doses of ibuprofen also increase the pharmacodynamic efficacy of ibuprofen [12, 13] has led to standardized use of ibuprofen regimens with doses as high as 600 mg. There seems to be little available information documenting the effect of high-dose ibuprofen regimens on acute inflammatory symptoms such as swelling and pain.

The aim of this trial was to compare the effect of a 3-day regimen of ibuprofen 600 mg × 4 with that of a regimen of paracetamol 1000 mg × 4 on acute postoperative swelling and pain and other inflammatory events after third molar surgery.

Methods

This was a randomized, double-blind, intra-patient, crossover study in which the patients acted as their own controls. The trial was approved by the Ethical Committee for Medical Research, Health Region II (S-91155) and Norwegian Medicines Agency (SLK no. 92–00963). The trial adhered to the GCP criteria including the Declaration of Helsinki [14].

Subjects

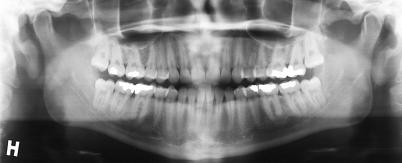

Females and males who were waiting for outpatient surgical removal of bilateral impacted third molars as evaluated by orthopantomograms (Figure 1), were identified from the waiting list at the clinic. Patients were asked to volunteer after receiving written information about the trial and an explanation as to the nature and intentions of the trial. Signed informed consent was obtained.

Figure 1.

Orthopantomograms showing the position of bilateral impacted third molars in the lower jaw.

Inclusion criteria were females and males between 18 and 40 years of age and weighing between 40 and 100 kg in compliance with the ASA class I physical status classification [15]. Exclusion criteria were any known acute or chronic disease. A negative self-report for overt renal or hepatic disease, asthma bronchiale, ulcus ventriculi or duodeni, choledoctal spasm, inflammatory gastrointestinal disease, unspecified symptoms from teeth not related to surgical intervention, known intolerance to the trial drugs, suspected or verified pregnancy, and medication within the previous 14 days (except peroral contraception) was required. Breast-feeding females were also excluded. In addition, surgery lasting more than 60 min, concomitant nontrial drugs during the observation period and surgical complications making the two surgical procedures noncomparable were also valid causes for exclusion.

Forty patients entered the trial as intention-to-treat patients, but four patients were excluded from the trial. One was a 31-year-old female, who lost the chlortetracycline (Aureomycin™ 3% ointment- Wyeth Lederle, Philadelphia, USA) -impregnated gauze drain on leaving the clinic after the second treatment (ibuprofen). She developed fibrinolysis of the blood clot (dry socket) necessitating wound revision under local anaesthethic and adjuvant analgesic therapy. Two patients (a 22-year-old female and an 18-year-old male ) did not return for the second operation (both paracetamol). One 26-year-old female patient did not complete the trial drug regimen during the first operation (paracetamol), but completed the second operation (ibuprofen) without divulging this fact until the end of the trial.

Thirty-six patients (26 females/, 10 males; 72.2% female/ : 27.8% male) with mean age of 23 (range 19–27) years, mean (95% CI) height 169.0 (166.1, 171.9) cm and mean (95% CI) weight 62.5 (59.1, 66.0) kg were used for statistical analyses as per-protocol patients.

Medications

The double-dummy technique was chosen to make the two trial regimens identical with respect to tablet shape, size and number of tablets. The trial drugs consisted of white ibuprofen tablets (600 mg each) and matching placebo tablets, or white paracetamol tablets (each 500 mg) and matching placebo tablets. Each trial drug dose consisted of one ibuprofen tablet and two placebo (paracetamol-like) tablets or two paracetamol tablets and one placebo (ibuprofen-like) tablet depending on the active drug regimen.

Production, packing and labelling of trial drugs were performed by DAK-Laboratoriet AS (Copenhagen, Denmark), for Nycomed Pharma AS (Roskilde, Denmark), according to a randomized list made after block randomization. Each set of trial drugs was given a number that corresponded to the inclusion number. According to randomization, the first trial drug regimen within each trial drug set was one of two possible trial drug regimens. One regimen consisted of racemic ibuprofen 600 mg (Ibuprofen™l; Nycomed Pharma AS, Copenhagen, Denmark) taken four times a day, starting 3 h after completion of surgery and lasting for a total of 3 days. On two subsequent postoperative days ibuprofen 600 mg was taken at 08.00, 12.00, 16.00 and 20.00 h. The other regimen was paracetamol 1000 mg (Pamol™; Nycomed Pharma AS) taken four times a day, starting 3 h after completion of surgery and lasting for a total of 3 days. On the subsequent 2 days paracetamol 1000 mg was taken at 08.00, 12.00, 16.00 and 20.00 h.

Surgery

Each patient had two similar surgical procedures using Xylocain-Adrenalin™ [lidocaine-hydrochloride 2% + epinephrine (adrenaline) 12.5 µg ml−1, Astra, Södertälje, Sweden] as local anaesthetic. No concomitant medication was used during surgery other than the local anaesthetic. Surgery was carried out to remove a mandibular third molar according to a standardized technique, including mucosal flap elevation, bone removal and suturing, as described previously [16]. If it was considered necessary to remove an ipsilateral maxillary third molar during surgery, this was also done. This was only done on those patients with bilaterally positioned maxillary third molars to avoid a dissimilar operative procedure on the next surgical occasion. Thirteen of the 36 patients also had a bilaterally positioned maxillary third molar, which was removed during the same surgical occasion as the ipsilateral mandibular third molar.

Mean (95% CI) time between operations was 42 (33, 52) days. The mean ± SD amount of local anaesthetic used for and added under surgery was almost identical in both treatment groups, 4.1 ± 1.6 ml and 0.04 ± 0.1 ml with mean (95% CI) differences 0.02 (−0.03, 0.07) ml, and 0.0 (−0.05, 0.05) ml, respectively. Waiting time before surgery was 3 min in both treatment groups. Mean time ± SD for surgery was 15.15 ± 6.32 min for the paracetamol and 14.58 ± 6.10 min for the ibuprofen group, with mean (95% CI) difference 00.16 (−0.71, 1.14) min.

Objective and subjective measurements

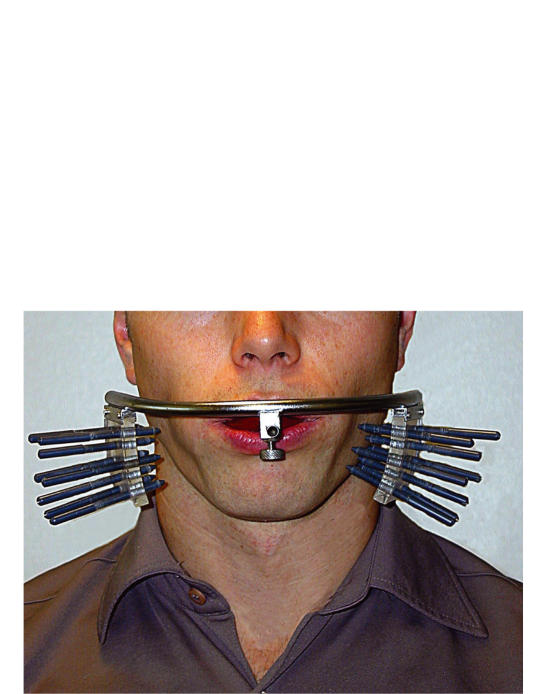

The clinical record form (CRF) was divided in two parts, a clinical CRF and a patient CRF. The patients received their CRF only after being instructed in its use. On the clinical CRF the investigator noted the results of objective clinical assessments of the patients preoperatively, on the third and sixth postoperative day. The method of measuring the primary objective variable, postoperative swelling, has been described previously [17, 18] and consisted of an exact measurement of the distance from a face bow to the facial skin area adjacent to the operated mandibular third molar (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Measurement of the left lateral facial contour adjacent to the surgical site before third molar surgery. Changes in the distance between the facial soft tissue contour adjacent to the surgical site and the face-bow are measured by eight adjustable pins.

Secondary variables such as objective measurement of mouth-opening with a ruler [17] and subjective assessment of clinical postoperative complications such as wound infections, dry socket, and presence of haematomas/ecchymoses were noted by the investigator at the control visit on the third and sixth postoperative day on the clinical CRF. The presence (yes/no) of wound infection or dry socket was assessed by the investigator depending on clinical appearance, presence of pus, or absence of normal coagulation, odour arising from the alveolus and extraordinary pain by slight bone provocation. Haematomas/ecchymoses were assessed with a ruler along the longest possible diameter as ‘none’ (1), ‘less than 4 cm’ (2), ‘between 4 and 10 cm’ (3) and ‘more than 10 cm’ (4). At the end of each observation period (sixth postoperative day) the patients were asked if they had taken any concomitant nontrial drugs.

On the sixth postoperative day, after completing the last trial drug regimen, a drug regimen preference score on the clinical CRF was shown to the patient by the investigator. Drug regimen preference score was made on a vertical 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) running from ‘Second postoperative course best’ (0 mm) to ‘First postoperative course best’ (100 mm) via ‘No difference’ marked on the VAS halfway (50 mm) between the two opposing scores.

Other secondary subjective variables such as pain, drug regimen efficacy score, postoperative bleeding and occurrence of adverse effects including description and duration of adverse drug effects were also noted by the patients on their CRFs. Pain intensity (PI) was rated on vertical [19] VAS running from ‘No pain’ (0 mm) to ‘Pain cannot be worse’ (100 mm). On the day of surgery the PI was recorded every hour for 11 h with extra recordings at 3.5, 6.5 and 9.5 h, starting immediately after completing the operation. On the first and second postoperative days PI was scored at 08.00, 12.00, 16.00 and 20.00 h. The sum pain intensity (SUMPI) was calculated by adding all PIs from 0.5 h after drug intake up to 11 h after surgery. All half-hour scores were multiplied by 0.5 before the addition. Sum PI was also calculated for each of the three time intervals after the first drug dose (SUMPI3.5−6, SUMPI6.5−9 and SUMPI9.5−11) on the day of surgery and for the whole day of surgery (SUMPI 3.5–11).

On the third postoperative day after each operation the patients made a global (overall) efficacy assessment of the particular drug regimen on a 100 mm VAS running from bad (0 mm) to good (100 mm). Postoperative bleeding was recorded by the patients on a four-point verbal rating scale 4 h postoperatively, at bedtime on the day of surgery and at bedtime each day for the next 5 postoperative days. Postoperative bleeding was scored according to the alternatives ‘No bleeding’ (1), ‘Taste of blood’ (2), ‘Can spit a little blood’ (3) or ‘Can spit a lot of blood’ (4) according to Hepsø et al. [20]. Every evening starting from the day of surgery and lasting until the end of the fifth postoperative day the patients answered with yes or no to the question ‘Have you experienced any other effect than pain relief from the trial drugs?’. If yes, the nature of the adverse effect and a time estimate of the duration of the effect were recorded. The patient CRFs were collected by the investigator on the sixth postoperative day after completing each trial drug regimen.

Statistical analyses

After descriptive analyses all pertinent data were subsequently analysed with the one sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with respect to normality. According to normality, continuous data were analysed with the two-tailed Wilcoxon signed ranks test or the two-tailed paired samples t-test. All data were analysed using the SPSS for Windows (version 8.0.0) statistical package [21]. The significance level was 5%. Previous trials found about 30% swelling reduction after paracetamol 1000 mg regimens on the third postoperative day compared with placebo [8, 9]. The difference between two active drugs was expected to be less than the difference in swelling reduction between active drug and placebo. Hence, the trial was planned to test the null hypothesis that the mean swelling difference between the active drug regimens was 15% (equals 6 mm mean swelling reduction). From pretrial two-tailed sample-size analysis (α = 0.05, effect size 6.0, known SD of difference 13.2, power of 80%, constant = 0) we found the required n to be 40 patients. A two-tailed post hoc analysis of the present swelling data (α = 0.05, n = 36 paired cases, mean difference = −0.33, SD difference = 13.0, constant = 6.0) showed that our trial yielded a power of 81.1%. The sample size and power analyses were made using the t-test for paired samples (Samplepower v.1.0; SPSS Inc).

Results

Postoperative swelling

There was no statistically significant difference between a 3-day regimen of paracetamol 1000 mg × 4 or ibuprofen 600 mg × 4 with respect to effect on acute p.o. swelling after third molar surgery (Table 1). Measured swelling was 1.8% lower (P = 0.88, two-tailed paired samples t-test) than that after ibuprofen on the third day after surgery, while swelling after ibuprofen was 2.3% lower (P = 0.96, paired samples t-test) than that after paracetamol on the sixth postoperative day. The magnitude of swelling was, however, for both groups far less than that observed on the third postoperative day.

Table 1.

Postoperative swelling and reduction of mouth opening (mean (SD)) after treatment with paracetamol 1000 mg × 4 or ibuprofen 600 mg × 4 for 3 days. Swelling measured on the third and sixth postoperative day following bilateral third molar surgery in a doubleblind, randomized, crossover trial. Swelling (mm) measured by face-bow and mouth opening (mm) by a ruler.

| Time after surgery | Paracetamol | Ibuprofen | Difference (95% CI) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swelling | ||||

| Third day | 18.4 (10.7) | 18.8 (14.4) | −0.3 (−4.7, 4.1) | 36 |

| Sixth day | 3.1 (4.6) | 2.9 (6.2) | 0.2 (−2.4, 2.8) | 36 |

| Mouth opening | ||||

| Third day | −10.8 (9.7) | −11.6 (10.5) | 0.8 (−1.8, 0.5) | 36 |

| Sixth day | −4.8 (7.0) | −6.6 (9.0) | 1.8 (−1.4, 5.0) | 36 |

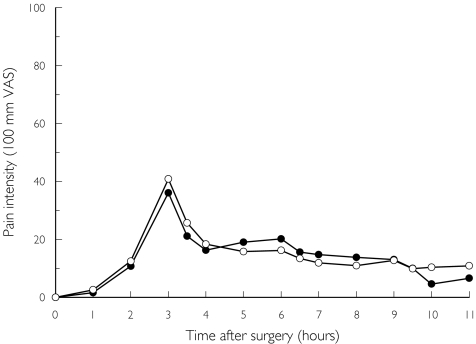

Pain and other effects

Figure 3 shows the time course of the PI following the two treatments on the day of surgery. The summed PI scores for the relevant dose intervals and the differences (95% CI) between treatments are shown in Table 2. All summed pain measurements showed a slight numerical superiority for ibuprofen, but no statistically significant difference between treatments (two-tailed Wilcoxon signed ranks test) difference, SUMPI3.5−6 (P = 0.25), and SUMPI6.5−9 (P = 0.14), except for the SUMPI9.5−11 interval (P = 0.04).

Figure 3.

The mean pain intensity scores assessed on the day of surgery by 36 patients who had bilaterally impacted third molars removed on two separate occasions. On one occasion they received paracetamol (•) 1000 mg × 4 for 3 days. On the other occasion they received ibuprofen (○) 600 mg × 4 for the same time period.

Table 2.

Pain intensity, sum pain intensity (SUMPI) and mean differences between treatments reported after paracetamol 1000 mg × 4 or ibuprofen 600 mg × 4 on the day of surgery. Trial medication started 3 h after end of surgery. Pain scored on a 100-mm VAS. Data presented as mean (SD) and mean differences (95% CI).

| Mean pain intensity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time after surgery (h) | Paracetamol | Ibuprofen | Mean difference | n |

| 0 | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.00, 0.00) | 36 |

| 1 | 1.6 (6.1) | 2.6 (6.6) | 1.0 (−4.0, 2.1) | 36 |

| 2 | 10.8 (21.9) | 12.4 (20.2) | −1.7 (−11.2, 7.8) | 36 |

| 3 | 36.1 (32.0) | 40.9 (34.9) | −4.8 (−15.4, 5.8) | 36 |

| 3.5 | 21.1 (19.6) | 25.7 (27.1) | −4.6 (−12.4, 3.3) | 36 |

| 4 | 16.3 (17.5) | 18.4 (25.4) | −2.1 (−10.4, 6.1) | 36 |

| 5 | 19.0 (19.9) | 15.8 (22.5) | 3.2 (−5.1, 11.5) | 36 |

| 6 | 20.1 (20.1) | 16.2 (22.2) | 3.9 (−3.4, 11.2) | 36 |

| 6.5 | 15.6 (16.9) | 13.4 (19.4) | 2.1 (−4.2, 8.5) | 36 |

| 7 | 14.8 (16.5) | 11.8 (16.9) | 2.9 (−3.4, 9.2) | 36 |

| 8 | 13.8 (16.9) | 10.9 (15.0) | 2.6 (−3.2, 8.4) | 35 |

| 9 | 13.0 (16.8) | 12.7 (16.3) | −2.2 (−8.6, 4.0) | 30 |

| 9.5 | 10.0 (15.1) | 9.9 (14.4) | −1.8 (−7.2, 3.6) | 27 |

| 10 | 4.6 (6.4) | 10.4 (14.6) | −4.2 (−9.8, 1.3) | 22 |

| 11 | 6.6 (10.5) | 10.9 (17.3) | −4.3 (−11.0, 2.4) | 21 |

| Summed pain measures | ||||

| SUMPI3.5−6 | 66.0 (59.6) | 63.3 (77.1) | 2.7 (−21.2, 26.7) | 36 |

| SUMPI6.5−9 | 47.9 (54.6) | 40.7 (53.2) | 7.2 (−12.1, 26.5) | 36 |

| SUMPI9.5−11 | 11.1 (14.1) | 26.0 (38.6) | −14.9 (−29.0, −0.9)* | 27 |

| SUMPI3.5−11 | 124.4 (117.8) | 121.1 (157.4) | 3.3 (−47.7, 54.3) | 36 |

Significant difference (P < 0.05, two-tailed Wilcoxon signed ranks test).

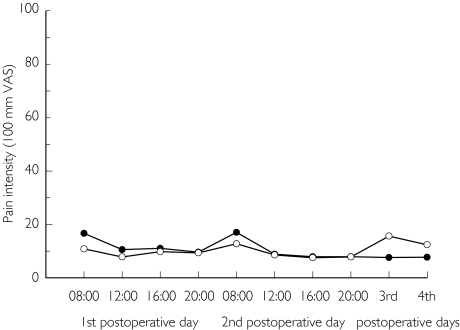

Figure 4 shows the time course of the PI after the treatments on the first to the fourth postoperative day. The differences (95% CI) between treatments are shown in Table 3. There was less pain after ibuprofen at 08.00 h (P = 0.04, two-tailed Wilcoxon signed ranks test) on the first postoperative day, but apparently no difference for the remaining observation period.

Figure 4.

The mean pain intensity scores assessed on the first to the fourth postoperative day by 36 patients who had bilaterally impacted third molars removed on two separate occasions. On one occasion they received paracetamol (•) 1000 mg × 4 for 3 days. On the other occasion they received ibuprofen (○) 600 mg × 4 for the same time period.

Table 3.

Pain intensity first to fourth postoperative day, global efficacy, drug preference score and mean difference between treatments after paracetamol 1000 mg × 4 or ibuprofen 600 mg × 4 for 3 days. Pain scored on 100 mm VAS. Data presented as mean (SD) and mean differences (95% CI).

| Mean pain intensity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time after surgery | Paracetamol | Ibuprofen | Mean difference | n |

| First postoperative day | ||||

| 08.00 h | 16.7 (18.3) | 10.8 (15.4) | 6.7 (1.1, 12.3)* | 35 |

| 12.00 h | 10.6 (16.1) | 7.9 (12.4) | 2.8 (−2.1, 7.6) | 36 |

| 16.00 h | 11.1 (16.5) | 9.8 (18.9) | 1.3 (−4.3, 6.8) | 36 |

| 20.00 h | 9.6 (15.3) | 9.4 (17.1) | 0.3 (−3.8, 4.3) | 36 |

| Second postoperative day | ||||

| 08.00 h | 17.1 (22.5) | 12.8 (21.1) | 4.1 (−4.5, 12.6) | 35 |

| 12.00 h | 8.8 (14.6) | 8.6 (15.0) | 0.3 (−4.4, 4.9) | 36 |

| 16.00 h | 7.9 (14.3) | 7.6 (15.6) | 0.3 (−4.3, 4.9) | 36 |

| 20.00 h | 7.9 (16.0) | 7.9 (16.3) | 0.1 (−5.0, 5.1) | 36 |

| Third postoperative day | ||||

| Bedtime | 7.6 (15.4) | 15.7 (23.2) | −8.0 (−16.1, 0.0) | 36 |

| Fourth postoperative day | ||||

| Bedtime | 7.7 (14.3) | 12.4 (20.0) | −4.7 (−10.0, 0.5) | 36 |

| Global efficacy of drug regimen | 79.1 (25.6) | 79.7 (24.8) | −0.5 (−9.9, 8.9) | 36 |

| Drug regimen preference | 15.7 (18.0) | 8.6 (14.4) | 7.1 (−2.6, 16.7) | 36 |

Significant difference (P < 0.05, two-tailed Wilcoxon signed ranks test).

There was no statistically significant difference between treatments with respect to the patients’ global (overall) efficacy evaluation (P = 0.94) or drug regimen preference (P = 0.14). Data are shown in Table 2. There was no statistically significant difference (P = 0.8) between the treatments with respect to mouth opening on the third or the sixth postoperative day (Table 1). All analyses were done with the two-tailed Wilcoxon signed ranks test.

No complications, such as wound infection or dry socket were seen when the patients were treated with paracetamol during this study. Two (5.6%) of the 36 patients (two females 25 and 21 years, respectively) developed dry socket observed on the sixth postoperative day when treated with ibuprofen 600 mg.

There was apparently no difference between treatments with respect to haematomas/ecchymoses and postoperative bleeding following treatment with paracetamol or ibuprofen (data not shown).

The gender (F/M) distribution of the patients reporting adverse effects were on the day of surgery (2F/1M, total 8.3%), and the first (6F/1M/, total 19.4%), second (4F/1M/, total 13.9%), and third postoperative days (1F/0M/, total 2.8%); there were no reports on the fourth and fifth postoperative days after paracetamol. After ibuprofen the reports were on the day of surgery (4F/2M/, total 16.7%), and the first (3F/1M/, total 11.1%), second (2F/1M/, total 8.3%), third (2F/1M/, total 8.3%), fourth (1F/0M/, total 2.8%), and fifth postoperative days (1F/0M/, total 2.8%).

The severity of all adverse effects was categorized as mild to moderate and ranged from tiredness, nausea to gastrointestinal complaints. There was apparently no difference between treatments with regard to the number and types of adverse effects reported.

Discussion

Ibuprofen enjoys the clinical reputation of being a better ‘anti-inflammatory’ drug than paracetamol. In the present trial, even a high dose regimen of ibuprofen failed to exert greater anti-inflammatory effects than paracetamol in traditional doses, at least with postoperative swelling and secondary pain as indicators of inflammation. Hence, the present findings support the report by Voigt [11] stating no anti-inflammatory advantage for ibuprofen 400 mg × 4 daily compared with paracetamol 1000 mg.

Ibuprofen is ranked as a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, thereby indicating an ‘anti-inflammatory’ effect. However, using postoperative or post-traumatic tissue swelling in human patients as the cardinal symptom of inflammation shows that the ‘anti-inflammatory’ effect of ibuprofen is not convincingly demonstrated. Ibuprofen 400 mg × 3 vs placebo did not show any statistically significant swelling reduction after third molar surgery [10] or ankle joint injuries [22]. Ibuprofen 2400 mg day−1, given either as single doses of 400 mg [23] or 800 mg [24] compared with placebo in patients with ankle sprains, did not show any difference between treatments. Although subjective evaluation was used to assess the post-traumatic swelling in several of the studies, the apparent lack of effect on swelling of high-dose ibuprofen regimens in acute post-traumatic swelling of nondental origin is striking. On the other hand, an antiswelling efficacy of high-dose ibuprofen comparable with that following a paracetamol 1000 mg regimen, which in fact reduces swelling compared with placebo by 30% following third molar surgery, might be termed a clinically satisfactory result.

The present finding contrasts with clinical trials that report superior analgesic efficacy of single doses of ibuprofen 400 mg over paracetamol 1000 mg [5, 6]. Our trial did not show any convincing analgesic superiority of ibuprofen 600 mg compared with paracetamol 1000 mg when both drugs were given four times daily for 3 days. Further, ibuprofen given as multiple doses of 1200 mg day−1 or 2400 mg day−1 showed the same magnitude of pain improvement as multiple doses of paracetamol 4000 mg day−1 in patients suffering from osteoarthritis of the knee [25].

Single-dose studies with high ibuprofen doses fail to show a dose-dependent improvement of analgesic efficacy. Ibuprofen in doses of 800 mg was superior to placebo following oral surgery [26] and argon-laser induced pain [27], but not ibuprofen in doses of 400 mg. These papers lend support to our view that there is little evidence of an increased analgesic potency (pain-relieving effect) of ibuprofen in doses above 400 mg in moderate to low inflammatory conditions. However, it should be emphasized that this view does not exclude the possibility of a longer duration of analgesic effect of high ibuprofen doses caused by dose-dependent pharmacokinetic alterations.

The adverse effect profile of both treatments was apparently similar, but the appearance of dry sockets (fibrinolysis) was seen only in the ibuprofen-treated group. It is known that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may influence platelet function while paracetamol 1000 mg has apparently no significant effects on platelet function [28–30]. Ibuprofen is usually reported to have a minor effect on platelet function [31], but this effect was significantly different from placebo when a regimen of ibuprofen 800 mg was used [32]. We do not exclude the possibility that even a short-term ( 3-day) regimen of ibuprofen 600 mg × 4 may actually increase the risk of developing adverse effects associated with platelet function.

We conclude that a multiple dose regimen with high ibuprofen (600 mg × 4 daily) does not offer any clinical advantages compared with a traditional paracetamol regimen (1000 mg × 4 daily) with respect to alleviation of acute postoperative swelling and pain after third molar surgery. Based on the present results and published data we infer that ibuprofen doses higher than 400 mg do not increase its anti-inflammatory potency (e.g. effect on pain and swelling) compared with paracetamol following third molar surgery.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Nycomed Pharma AS, Roskilde, Denmark, for the gift and packing of the trial medication.

References

- 1.Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ, Wiffen PJ. Oral ibuprofen and diclofenac in postoperative pain: a quantitative systematic review. Eur J Pain. 1998;2:285–291. doi: 10.1016/s1090-3801(98)90027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Wan Po A, Zhang WY. Analgesic efficacy of ibuprofen alone and in combination with codeine or caffeine in post-surgical pain: a meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;53:303–311. doi: 10.1007/s002280050383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper SA. Five studies on ibuprofen for postsurgical dental pain. Am J Med. 1984;77(1A):70–77. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(84)80022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forbes JA, Kehm CJ, Grodin CD, Beaver WT. Evaluation of ketorolac, ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and an acetaminophen-codeine combination in postoperative oral surgery pain. Pharmacotherapy. 1990;10:94S–105S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper SA, Schactel BP, Goldman E, Gelb S, Cohn P. Ibuprofen and acetaminophen in the relief of acute pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;29:1026–1030. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1989.tb03273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehlisch DR, Sollecito WA, Helfrick JF, et al. Multicenter clinical trial of ibuprofen and acetaminophen in the treatment of postoperative dental pain. J Am Dental Assoc. 1990;121:257–263. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1990.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Insel PA. Analgesic-antipyretics and antiinflammatory agents. Drugs employed in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and gout. In: Gilman AG, Rall TW, Nies AS, Taylor P, editors. Goodman and Gilman's the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 8. New York: Pergamon Press; 1990. pp. 638–681. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skjelbred P, Løkken P. Paracetamol versus placebo. Effects on post-operative course. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1979;15:27–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00563555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skjelbred P, Løkken P, Skoglund LA. Postoperative administration of acetaminophen to reduce swelling and other inflammatory events. Curr Ther Res. 1984;35:377–385. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Løkken P, Olsen I, Bruaset I, Norman-Pedersen K. Bilateral surgical removal of impacted lower third molar teeth as a model for drug evaluation. A test with ibuprofen. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1975;8:209–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00567117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voigt W. Die antiphlogistische Therapie mit Ibuprofen im Vergleich mit Paracetamol in der Oralchirurgie. ZWR. 1992;101:430–435. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dionne RA, Campbell RA, Cooper SA, Hall DL, Buckingham B. Suppression of postoperative pain by preoperative administration of ibuprofen in comparison to placebo, acetaminophen, and acetaminophen plus codeine. J Clin Pharmacol. 1983;23:37–43. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1983.tb02702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laska EM, Sunshine A, Marrero I, Olson N, Siegel C, McCormick N. The correlation between blood levels of ibuprofen and clinical analgesic response. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1986;40:1–7. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1986.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anonymous. Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) for Trials on Pharmaceutical Products. Geneva: WHO Technical Report Series; 1995. No 850, Annex 3, [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owens WD, Felts JA, Spitznagel EL. ASA physical classifications: a study of consistency of ratings. Anesthesiology. 1978;49:239–243. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skjelbred P, Album B, Løkken P. Acetylsalicylic acid vs paracetamol: effects on postoperative course. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1977;12:257–264. doi: 10.1007/BF00607424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Album B, Olsen I, Løkken P. Bilateral surgical removal of impacted third molar teeth as a model for drug evaluation: a test with oxyphenbutazone (Tanderil) Int J Oral Surg. 1977;6:177–189. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(77)80051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skoglund LA, Pettersen N. Effects of acetaminophen after bilateral oral surgery: double dose twice daily versus standard dose four times daily. Pharmacotherapy. 1991;11:370–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breivik EK, Skoglund LA. Comparison of present pain intensity assessments on horizontally and vertically oriented visual analogue scales. Meth Findings Clin Exp Pharmacol. 1998;20:719–724. doi: 10.1358/mf.1998.20.8.487509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hepsø HU, Løkken P, Bjørnson J, Godal HC. Double-blind crossover study of the effect of acetylsalicylic acid on bleeding and postoperative course after bilateral oral surgery. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1976;10:217–225. [Google Scholar]

- 21.SPSS for WindowsRel800. Chicago: SPSS Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fredberg U, Hansen PA, Skinhøj A. Ibuprofen in the treatment of acute ankle joint injuries. A double-blind study. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17:564–566. doi: 10.1177/036354658901700419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dupont M, Beliveau P, Theriault G. The efficacy of antiinflammatory medication in the treatment of the acutely sparined ankle. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15:41–45. doi: 10.1177/036354658701500106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersson S, Fredin H, Lindberg H, Sanzen L, Westlin N. Ibuprofen and compression bandage in the treatment of ankle sprains. Acta Orthop Scand. 1983;54:322–325. doi: 10.3109/17453678308996578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradley JD, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Kalasinski LA, Ryan SI. Comparison of an antiinflammatory dose of ibuprofen, an analgesic dose of ibuprofen, and acetaminophen in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:87–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107113250203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winter L, Bass E, Recant B, Cahaly JF. Analgesic activity of ibuprofen (Motrin) in postoperative oral surgical pain. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978;45:159–166. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(78)90079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielsen JC, Bjerring P, Arendt-Nielsen L, Petterson KJ. A double-blind, placebo controlled, cross-over comparison of the analgesic effect of ibuprofen 400 mg and 800 mg on laser-induced pain. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30:711–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb03840.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cronberg S, Wallmark E, Söderberg I. Effect on platelet aggregation of oral administration of 10 non-steroidal analgesics to humans. Scand J Haematol. 1984;33:155–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1984.tb02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seymour RA, Williams FM, Oxley A, et al. A comparative study of the effects of aspirin and paracetamol (acetaminophen) on platelet aggregation and bleeding time. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;26:567–571. doi: 10.1007/BF00543486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niemei T, Tanskanen P, Taxell C, Juvela S, Randell T, Rosenberg P. Effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on hemostasis in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1999;11:188–194. doi: 10.1097/00008506-199907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bozzo J, Escolar G, Hernández M-R, Galán A-M, Ordinas A. Prohemorrhagic potential of dipyrone, ibuprofen, ketorolac, and aspirin: mechanisms associated with blood flow and erythrocyte deformability. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2001;38:183–190. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200108000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunt RH, Bowen B, Mortensen E, et al. A randomised trial measuring fecal blood loss after treatment with rofecoxib, ibuprofen, or placebo in healthy subjects. Am J Med. 2000;109:201–206. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00470-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]