Abstract

Aims

The aims of this study were to examine the in vitro enzyme kinetics and CYP isoform selectivity of perhexiline monohydroxylation using human liver microsomes.

Methods

Conversion of rac-perhexiline to monohydroxyperhexiline by human liver microsomes was assessed using a high-performance liquid chromatography assay with precolumn derivatization to measure the formation rate of the product. Isoform selective inhibitors were used to define the CYP isoform profile of perhexiline monohydroxylation.

Results

The rate of perhexiline monohydroxylation with microsomes from 20 livers varied 50-fold. The activity in 18 phenotypic perhexiline extensive metabolizer (PEM) livers varied about five-fold. The apparent Km was 3.3 ± 1.5 µm, the Vmax was 9.1 ± 3.1 pmol min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein and the in vitro intrinsic clearance (Vmax/Km) was 2.9 ± 0.5 µl min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein in the extensive metabolizer livers. The corresponding values in the poor metabolizer livers were: apparent Km 124 ± 141 µm; Vmax 1.4 ± 0.6 pmol min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein; and intrinsic clearance 0.026 µl min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein. Quinidine almost completely inhibited perhexiline monohydroxylation activity, but inhibitors selective for other CYP isoforms had little effect.

Conclusions

Perhexiline monohydroxylation is almost exclusively catalysed by CYP2D6 with activities being about 100-fold lower in CYP2D6 poor metabolizers than in extensive metabolizers. The in vitro data predict the in vivo saturable metabolism and pharmacogenetics of perhexiline.

Keywords: CYPD2D6, cytochrome P450, in vitro, in vivo extrapolation, metabolism, perhexiline, polymorphism

Introduction

Perhexiline is an effective antianginal drug but can cause severe toxicity, notably hepatotoxicity [1–5] and peripheral neuropathy [6–10]. Its pharmacokinetics are complex as it has a long elimination half-life of days to weeks [11], the steady-state plasma concentration to dose ratio varies more than a 100-fold [12], and the systemic clearance is saturable [13]. Perhexiline undergoes oxidative metabolism to produce a number of mono- and di-hydroxylated metabolites. The major initial products are the diastereomers cis-4-axial- (M1) and trans-4 equatorial- (M3) monohydroxyperhexiline [11]. The major metabolite detected in plasma is M1, which occurs at higher concentrations than perhexiline [14, 15]. Shah et al.[9] in 1982 found that 50% of 20 patients with perhexiline neuropathy had debrisoquine hydroxylation ratios> 12.6 compared with none out of 14 perhexiline-treated patients who did not have neuropathy. The same group later showed that three of four patients with perhexiline liver injury were poor debrisoquine hydroxylators, and the fourth had a severely impaired hydroxylation capacity [16]. Cooper et al. confirmed that the genetic control of impaired oxidation was identical for debrisoquine, sparteine and perhexiline [15], and that perhexiline phenotyping clearly separated the poor and extensive metabolizer phenotypes [17]. Although the in vivo studies strongly support a role for CYP2D6 in the metabolism of perhexiline, this has not been confirmed by in vitro studies. This communication reports a systematic investigation of the in vitro metabolism of perhexiline.

Methods

Materials

Rac-perhexiline maleate was obtained from Fawns and McAllen (Croydon, Australia), monohydroxyperhexiline from Marion Merrell Dow (Kansas City, KS, USA), furafylline from Hoffmann La Roche (Basel, Switzerland), sulphaphenazole from Ciba-Geigy (Sydney, Australia), R,S-mephenytoin from Sandoz Ltd (Basel, Switzerland), and gestodene was a gift from FP Guengerich, Vanderbilt University. Di-N-hexylamine, trans - 4 - nitrocinnamoyl chloride, quinidine sulphate, diethyldithiocarbamate, coumarin, glucose-6-phosphate, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and NADP were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). All other reagents were of analytical reagent grade.

Human liver microsomes

Microsomes were prepared from human liver samples obtained from renal transplant donors with the consent of the next-of-kin and the approval of the Flinders Medical Centre Committee on Clinical Investigation [18]. Microsomal samples from one genotyped CYP2D6*4A/*4A homozygote poor metabolizer liver (HLM24) were kindly supplied by Dr A. Somogyi of the Department of Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology, The University of Adelaide. This was an operative biopsy specimen obtained with informed consent of the patient and with the approval of the Royal Adelaide Hospital Research Ethics Committee.

Microsomal incubations were carried out at 37 °C for 120 min in a total volume of 1 ml 0.1 m phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and contained human liver microsomes (1 mg), perhexiline maleate (0.25–200 µm added as stock dissolved in methanol to give a final methanol concentration of 0.5% v/v), and NADPH generating system comprising 1 mm NADP, 10 mm glucose-6-phosphate, 2 IU glucuose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and 5 mm MgCl2. Incubations were terminated by cooling on ice and addition of 1.2 ml di-ammonium hydrogen phosphate (1 m aqueous solution), 100 µl tri-N-octylamine (29 mg 100 ml−1 in dichloromethane) and 100 µl di-N-hexylamine (29.3 µm in methanol) as the internal standard. Perhexiline and internal standard were omitted from blank incubations. Mixtures were extracted with dichloromethane : isopentane (2 : 3 v/v; 8 ml) and the upper organic layer was decanted and evaporated to dryness. Derivatizing reagent (100 µl of 0.1 g trans-4-nitrocinnamoyl chloride in 10 ml anhydrous acetonitrile) was added to the extracts. After a 30-min reaction period, 100 µl of 0.25 m sodium carbonate were added and the mixture was allowed to stand for 5 min. Finally, 100 µl of 0.05 m ammonium hydrogen phosphate/acetonitrile (1 : 1 v/v) were added, the solution was centrifuged and 100 µl of the clear supernatant were injected onto the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) column.

The HPLC system comprised an ICI model LC1110 solvent delivery system, an ICI LC1200 UN/VIS absorbance detector set at 340 nm, a Waters Intelligent sample processor (WISP) and a SE120 BBC Goertz Metrawatt chart recorder. The column was an Altima phenyl reverse-phase column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 µm particle size). The mobile phase consisted of 10 mm ammonium acetate in acetonitrile (54%)/distilled water (46%) at a flow rate of 2 ml min−1. The retention times for monohydroxyperhexiline, internal standard and perhexiline were 7.0, 10.9 and 22 min, respectively. This assay system did not distinguish between M1 and M3. Peak height ratios (monohydroxyperhexiline : internal standard) were used to quantify the metabolite. Standard curves were linear over the concentration range 0.1–1.5 µm monohydroxyperhexiline. The extraction efficiency of the metabolite was 66.5 ± 4.9% at 0.25 µm and 64.7 ± 6.3% at 1.0 µm. The corresponding values for the internal standard at the same concentrations were 98.4 ± 5.9% and 101 ± 8.4%, respectively. The within-day precision for replicate incubations was < 12% at both low (0.5 µm) and high (10 µm) perhexiline (substrate) concentrations. Rates of formation of monohydroxyperhexiline were linear with microsomal protein concentration to at least 1 mg ml−1 and with time to 120 min.

CYP isoform selective inhibitors were screened for effects on monohydroxyperhexiline formation rate at a perhexiline concentration of 5 µm, close to the apparent Km. Furafylline (10 µm), quinidine (2.5 µm), and diethyldithiocarbamate (50 µm) were added as aqueous solutions. Coumarin (2.5 µm), sulphaphenazole (2.5 µm), S,R-mephenytoin (250 µm) and gestodene (100 µm) were dissolved in methanol so that the final concentration of methanol in the incubation was 0.5% (v/v). Methanol was added to the control incubations. Furafylline, diethyldithiocarbamate and gestodene were preincubated for 5 min with microsomes and NADPH generating system prior to the addition of substrate.

Enzyme activity vs. substrate concentration curves were first plotted as Eadie Hofstee plots and estimates of apparent Km and Vmax determined by linear regression analysis. These values were then used as the initial estimates in the nonlinear extended least squares regression modelling program, MK model [19], to produce final apparent Km and Vmax values. Values are given as means and standard deviations.

Results

The formation rate of monohydroxyperhexiline was assessed in 20 livers at a perhexiline concentration of 20 µm, which was saturating for phenotypic perhexiline extensive metabolizer (PEM) livers. The variation in activity in the PEM livers was approximately five-fold (from 3.4 to 17.5 pmol min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein). The rate of metabolite formation was very low in two livers H8 and H30 (0.7 and 0.2 pmol min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein, respectively), which were designated as phenotypic perhexiline poor metabolizer livers (PPM).

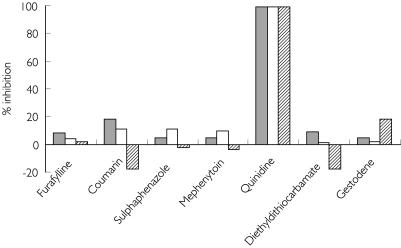

The inhibition by CYP selective inhibitors was investigated in three of the PEM livers [Figure 1]. Quinidine (CYP2D6) almost completely inhibited the activity in all three livers. The other inhibitors for CYP 1A2 (furafylline), 2A6 (coumarin), 2C9 (sulphaphenazole), 2C19 (S,R-mephenytoin), 2E1 (diethyldithiocarbamate) and 3A4 (gestodene) had essentially no effect (15% activation to 17% inhibition).

Figure 1.

Effect of CYP isoform selective inhibitors on perhexiline monohydroxylation with three phenotypic perhexiline extensive metabolizer livers. The perhexiline concentration was 5 µm. The inhibitor concentrations and incubation conditions are given in Methods and the values are the means of duplicate determinations. , H12; □, H25;

, H12; □, H25;  , H27.

, H27.

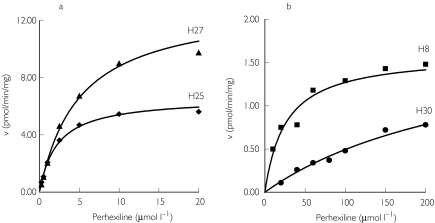

Kinetic studies were carried out with four of the PEM livers, and with the two livers showing defective hydroxylation (PPM livers). The substrate vs. activity curves for two PEM livers and the two PPM livers are shown in Figure 2. In all cases, the data fitted the Michaelis Menten model for a single enzyme. The apparent Km values for the PEM livers ranged from 1.9 µm to 5.0 µm with a mean of 3.3 ± 1.5 µm, and Vmax was between 6.6 pmol min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein and 13.2 pmol min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein (mean 9.1 ± 3.1 pmol min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein). The in vitro intrinsic clearance (Vmax/Km) was 2.9 ± 0.5 µl min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein.

Figure 2.

Kinetic plots for perhexiline monohydroxylation with (a) two phenotypic perhexiline extensive metabolizer livers (H25 and H27) and (b) two phenotypic perhexiline poor metabolizer livers (H8 and H30). The solid lines are those fitted to the data by nonlinear regression analysis. The data points are the mean of duplicate determinations.

Perhexiline monohydroxylation activity was low but measurable in the genotyped CYP2D6*4A/*4A PM liver (HLM24). The three perhexiline poor metabolizer livers showed much higher and more variable apparent Km values (124 ± 141 µm) and lower Vmax values (1.4 ± 0.6 pmol min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein). The mean in vitro intrinsic clearance for the poor metabolizer livers (0.026 ± 0.6 µl min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein) was about 110-fold lower than for the extensive metabolizer livers (2.9 ± 0.5 µl min−1 mg−1 microsomal protein).

Discussion

This study has confirmed the predominant metabolism of perhexiline by the polymorphic CYP2D6 isoform. The in vitro kinetics were consistent with the action of a single enzyme in all seven livers studied, and quinidine, a selective CYP2D6 inhibitor, essentially abolished formation of monohydroxyperhexiline. By contrast, inhibitors selective for a number of other CYP isoforms had little effect on perhexiline hydroxylation. The very low activity in two livers and in the genotypic CYP2D6*4A/4A poor metabolizer liver is consistent with the almost total inhibition of metabolism by quinidine in the extensive metabolizer livers.

With four extensive metabolizer livers, the apparent Km was low and in the range 2–5 µm. This is similar to the range of steady-state plasma perhexiline concentrations during treatment in vivo (0.5–1.5 µm), and therefore consistent with the nonlinear pharmacokinetics due to saturable metabolism reported in vivo[13].

Interestingly, on the basis of these results, the in vivo pharmacokinetics of perhexiline would be predicted to be linear in individuals genetically deficient in CYP2D6. In the absence of CYP2D6, other isoforms with higher apparent Km values are presumably responsible for formation of monohydroxyperhexiline. The apparent Km in this case is much higher than the therapeutic concentration range and first order (linear) kinetics would result. The in vitro intrinsic clearance in the poor metabolizer livers was about 100-fold lower than in the extensive metabolizer livers. This is consistent with the much lower dose rate required in poor metabolizer patients in vivo (as low as 50 mg week−1 to 7 mg day−1, compared with a dose range in extensive metabolizers of about 100–400 mg day−1), and with a ten-fold lower CL/F ratio in putative CYP2D6 poor metabolizer subjects compared with extensive metabolizer subjects [20, 21].

Perhexiline is uniquely effective as an antianginal agent due to its efficacy in patients refractory to maximal conventional therapy and its lack of negative inotropic effects. However, it has almost completely gone out of use outside Australia because of a lack of understanding of its pharmacogenetics and complex pharmacokinetics, and low therapeutic index. If the in vitro techniques used in this study had been available at the time perhexiline was developed, its eventual almost complete loss from the therapeutic armamentarium may have been avoided.

Acknowledgments

The work reported in this study was supported by grant 003216 from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. This work is part of a Royal Danish School of Pharmacy Masters thesis for L.B.S. and R.N.S.

References

- 1.Beaugrand M, Poupon R, Levy VG, Callard P, Lageron A, Lecomte D, et al. Hepatic lesions due to perhexiline maleate. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1978;2:579–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pessayre D, Bichara M, Degott C, Potet F, Benhamou JP, Feldmann G. Perhexiline maleate-induced cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1979;76:170–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forbes GB, Rake MO, Taylor DJ. Liver damage due to perhexiline maleate. J Clin Pathol. 1979;32:1282–1285. doi: 10.1136/jcp.32.12.1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hay DR, Gwynne JF. Cirrhosis of the liver following therapy with perhexiline maleate. NZ Med J. 1983;96:202–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paliard P, Vitrey D, Fournier G, Belhadjali J, Patricot L, Berger F. Perhexiline maleate-induced hepatitis. Digestion. 1978;17:419–427. doi: 10.1159/000198145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lhermitte F, Fardeau M, Chedru F, Mallecourt J. Polyneuropathy after perhexiline maleate therapy. BMJ. 1976;1:1256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6020.1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singlas E, Goujet MA, Simon P. Pharmacokinetics of perhexiline maleate in anginal patients with and without peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1978;14:195–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02089960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jallon P, Loiseau P, Orgogozo JM, Singlas E. Polyneuropathy with normal metabolism of perhexiline maleate. Ann Neurol. 1978;4:385–386. doi: 10.1002/ana.410040421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah RR, Oates NS, Idle JR, Smith RL, Lockhart JD. Impaired oxidation of debrisoquine in patients with perhexiline neuropathy. BMJ. 1982;284:295–299. doi: 10.1136/bmj.284.6312.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah RR, Oates NS, Idle JR, Smith RL, Lockhart JD. Prediction of subclinical perhexiline neuropathy in a patient with inborn error of debrisoquine hydroxylation. Am Heart J. 1983;105:159–161. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90297-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wright GJ, Leeson GA, Zeiger AV, Lang JF. Proceedings: The absorption, excretion and metabolism of perhexiline maleate by the human. Postgrad Med J. 1973;49(Suppl 3):8–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Button IK, Davies HR, Zeitz CJ, Wuttke RD, Horowitz JD. Adverse reactions to perhexiline during short and long-term therapy. Aust NZ J Med. 1993;23:599. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horowitz JD, Morris PM, Drummer OH, Goble AJ, Louis WJ. High-performance liquid chromatographic assay of perhexiline maleate in plasma. J Pharm Sci. 1981;70:320–322. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600700325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amoah AG, Gould BJ, Parke DV. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of perhexiline administered orally to humans. J Chromatogr A. 1984;305:401–409. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)83354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper RG, Evans DA, Price AH. Studies on the metabolism of perhexiline in man. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;32:569–576. doi: 10.1007/BF02455990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan MY, Reshef R, Shah RR, Oates NS, Smith RL, Sherlock S. Impaired oxidation of debrisoquine in patients with perhexiline liver injury. Gut. 1984;25:1057–1064. doi: 10.1136/gut.25.10.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper RG, Evans DA, Whibley EJ. Polymorphic hydroxylation of perhexiline maleate in man. J Med Genet. 1984;21:27–33. doi: 10.1136/jmg.21.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robson RA, Matthews AP, Miners JO, et al. Characterisation of theophylline metabolism in human liver microsomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;24:293–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holford NHG. MKMODEL: a modelling tool for microcomputers. Pharmacokinetic evaluation and comparison with standard computer programs. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1985;9:95. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sallustio BC, Westley IC, Morris RG. Pharmacokinetics of the antianginal agent perhexiline: relationship between metabolic ratio and steady state dose. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:107–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussein R, Charles BG, Morris RG, Rasiah RL. Population pharmacokinetics of perhexiline from very sparse, routine monitoring data. Ther Drug Monit. 2001;23:636–643. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]