Abstract

Objective To increase understanding of how the prison environment influences the mental health of prisoners and prison staff.

Design Qualitative study with focus groups.

Setting A local prison in southern England.

Participants Prisoners and prison staff.

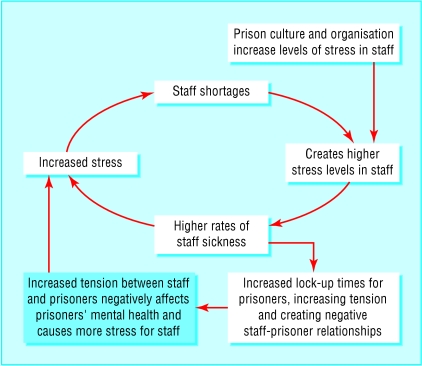

Results Prisoners reported that long periods of isolation with little mental stimulus contributed to poor mental health and led to intense feelings of anger, frustration, and anxiety. Prisoners said they misused drugs to relieve the long hours of tedium. Most focus groups identified negative relationships between staff and prisoners as an important issue affecting stress levels of staff and prisoners. Staff groups described a “circle of stress,” whereby the prison culture, organisation, and staff shortages caused high staff stress levels, resulting in staff sickness, which in turn caused greater stress for remaining staff. Staff shortages also affected prisoners, who would be locked up for longer periods of time, the ensuing frustration would then be released on staff, aggravating the situation still further. Insufficient staff also affected control and monitoring of bullying and reduced the amount of time in which prisoners were able to maintain contact with their families.

Conclusions Greater consideration should be given to understanding the wider environmental and organisational factors that contribute to poor mental health in prisons. This information can be used to inform prison policy makers and managers, and the primary care trusts who are beginning to work in partnership with prisons to improve the mental health of prisoners.

Introduction

The mental health of prisoners is a particular concern,1–3 with suicide rates six times higher than in the general population.4,5 Much of the literature on mental health of prisoners has focused on epidemiological prevalence studies of formal mental health problems. An Office for National Statistics study found that 14% of female prisoners and 7% of male prisoners have a psychotic illness6 compared with an overall figure of 0.5% in the general population.7 Remand prisoners (especially women) experience higher rates of depression than sentenced prisoners.6 Mental health, however, has been described as how people, communities, and organisations think and feel about themselves and their experience of mental wellbeing rather than just an absence of mental illness.8

Although social and environmental factors are known to affect mental health,9 little is known about the impact of prison environment. The World Health Organization's “Health in Prisons Project” recommends the use of a “settings approach” to assess the health impact of the prison environment to promote health among prisoners.10 This focus group study was in response to the 1999 joint Home Office/Department of Health document The Future Organisation of Prison Health Care, which recommends that each prison carries out an assessment of health needs and develops a local health improvement programme.11

We collected qualitative data for the health needs assessment in a local prison to increase understanding of how the prison environment influences the mental health of prisoners and prison staff.

Methods

This study took place within a local prison in a semirural setting in southern England. The prison is a category B prison (medium security), with 500 local remand and sentenced male prisoners and a female training prison (a rehabilitation unit) with 90 female prisoners from England and Wales, including overseas nationals We gained permission to hold focus groups within the prison from the prison governor. Focus groups were widely advertised to try to ensure that all those who wanted to attend were able to. Random sampling was not appropriate because of issues around consent within a prison setting.12 All participants attended as volunteers. A full explanation of the purpose and ground rules regarding confidentiality was given at the start of each focus group. No prison staff attended the prisoner focus groups.

We conducted seven focus groups that provided a wide representation of views and sufficient saturation (so eventually no new ideas emerge)13 and included remand, sentenced, female prisoners, and rule 45 prisoners (prisoners at risk of harm from the main prison population). Prison staff groups included uniformed, non-uniformed, and healthcare staff. Homogeneity within each group encouraged group members to participate equally.14

The group schedules were developed with the needs assessment project group (which included a prison doctor, nurse, and health centre manager, a prison governor, two public health doctors, a health promotion specialist, and a forensic psychiatrist) and used a funnel structure.13 Questions were worded in the third person to make it easier for respondents to give less personal details about themselves, and wording used straightforward language.15 The schedules were piloted with staff and prisoners. Each group had a moderator, a note taker, and an observer; all were employed by the NHS and not aligned to the prison service. All group members consented to the discussion being taped, and we explained that all material would be made anonymous. Each group lasted about 1.5 hours and refreshments were provided. No payments or inducements were given as this may have biased participation.

Analysis consisted of an initial debriefing with a summary developed from the notes.16 To enhance validity17 we gave a written summary to the moderator, the observer, and focus group attendees and requested feedback on content and emphasis. We carried out a content analysis, followed by a thematic analysis using a framework adapted from Vaughn et al12 to prioritise topics and enhance validity.14 JN carried out the thematic analysis in consultation with the other two authors. All authors took part in the focus groups. Insufficient resources meant tapes were not fully transcribed, though they were listened to in full and quotes withdrawn to illustrate issues raised.

Results

In total 31 prisoners (18 men, 13 women) and 21 prison staff (15 men, 6 women) attended focus groups. The results reflect views held by the majority. In the thematic analysis we placed greater emphasis on repeated themes (especially those repeated by more than one group), initially raised themes, strong feelings, or themes of long discussions.12 We have included discordant views to highlight differing experiences or perceptions of individuals and groups.

Key factors of the prison environment that influenced prisoners' mental health included isolation and lack of mental stimulation, drug misuse, negative relationships with prison staff, bullying, and lack of family contact. Key issues that influenced the mental health of staff included perceived lack of management support, the negative work culture, staff safety, and high stress levels increasing staff sickness, which in turn created higher stress levels.

Prisoners

Isolation and lack of mental stimulation

Remand and sentenced prisoners and uniformed staff emphasised the negative effect on prisoners' mental health of being locked up for as long as 23 hours a day. Remand prisoners do not normally work or have access to education, while many sentenced prisoners had limited access to both. Prisoners discussed how lack of activity and mental stimulation led to extreme stress, anger, and frustration (box 1).

The focus groups thought that any activity, whether it was exercise, work, or education, was beneficial. The focus group of non-uniformed staff thought that education was particularly important for prisoners, especially as many prisoners have limited literacy skills.

Box 1: Impact of isolation and lack of activity

Having something like a TV to focus your mind on, at the end of the day you've got nothing to focus your mind on, with no books to stimulate your mind, no papers to stimulate your mind... papers and TV are your link to the outside world. You've got nothing to stimulate your mind, you're just left staring at four blank walls (male prisoner 1)

... head going round and round, thinking too much... just feel like banging my head (male prisoner 2)

... not letting me get to education, not giving me a chance to work, not giving me a chance to do anything... you build up anger, you know what I mean... It's going to release one day, it's just building up inside you and you got to hold it down, hold it down, hold it down (male prisoner 3)

Remand and sentenced prisoners described how the prison environment encouraged drug misuse as drugs provided a mental escape and helped to relieve the long hours of tedium. One prisoner described how he became addicted during a previous sentence, while uniformed staff described the negative impact of drug misuse on prisoners' health (box 2).

Box 2: Health impact of drug misuse

Also, this is the first time I've come into prison with an addiction, but I got my addiction through my last prison sentence, you understand. All the other times I went to prison I come out healthy, but the last time I come out worse (male prisoner 4)

You can walk into a cell, it's filthy, dirty... you look into his eyes and he's out of his head (prison staff 1)

Male remand and sentenced prisoners commented that they would often wait all their association time (free time out of cells on the prison landings) queuing for telephones and not make a call because of insufficient time and telephones. Female prisoners talked about not being able to maintain contact with their families and not having any control over external events (box 3).

Box 3: Lack of family contact

If you've got relatives out there who's ill, you can't do nothing about it, you can't, and that makes you feel ten times worse (female prisoner 1)

Negative relationship with prison staff

All the prisoner focus groups described a cycle of negative attitudes, whereby if an officer treated a prisoner badly, prisoners would make the officer's life hard, which caused more stress for officers. This was captured by a series of comments from the female focus group (box 4).

All prisoner focus groups (except sentenced prisoners) suggested that staff should have more training and be better valued and that more staff would reduce stress levels for prisoners. Remand prisoners described how fewer staff increased the amount of time spent in cells, which made prisoners more difficult to deal with, thereby increasing stress levels of staff and prisoners.

Box 4: Cycle of negative attitudes between prisoners and prison staff

The ones that are horrid hate their jobs and think they're sick of this and that's because we treat them like a piece of shit (female prisoner 2)

They respond to us and then we respond to them (female prisoner 3)

The good ones enjoy their jobs a lot more than others because they're being personable and we treat them with respect (female prisoner 4)

Bullying

Rule 45 prisoners (convicted for sex offences, child abuse, or vulnerable to abuse from other prisoners) emphasised bullying by other prisoners as an issue, although other prisoner focus groups did not discuss this but described bullying of prisoners by staff members (see above). One participant from the rule 45 group described how bullying from other prisoners affected their mental health (box 5).

Box 5: Bullying of vulnerable prisoners

The first night is terrifying, they call you names, they say they're going to hang you, it's literally what they say, they call you sex beast and hang them (male prisoner 5)

Some focus group members were resigned to bullying, saying you can't stop it, while others said that it still affects mental health and was the main reason for people on their wing becoming ill. Suggestions for reducing bullying involved having sufficient supervision by senior prison officers, especially at meal times.

Staff

Working environment and culture

The reduction in staffing levels and concurrent rises in numbers of prisoner over the past few years was frequently expressed as a cause of stress in staff. Inmates have less time out of cells now as there are fewer members of staff to supervise them, which increases tensions between staff and prisoners. This also leads to less job satisfaction for staff. Poor management style, lack of communication, insufficient information, and lack of continuity of care with prisoners were identified as factors that increased levels of stress in staff. Staff acknowledged their own contribution to stress in their jobs, describing how the macho culture in prisons made it difficult for prison officers to open up and talk about their problems.

The healthcare group had concerns about safety as some staff had to interview prisoners on their own in inadequate facilities. The whole group thought this was important, and it reflected the general sense of isolation. The non-uniformed staff placed less emphasis on their own stress levels at work but described how other staff members would offload their stress on them. The uniformed staff considered that stress was the most important thing affecting their health at work; an important aspect of this was the fear of violence (box 6).

Box 6: Causes of stress for prison staff

Reduced staffing levels

Only a couple of years ago there was enough time for staff to talk one to one with prisoners... you could identify prisoners who were having problems (prison staff 2)

Prison culture

Prison officers are meant to be well'ard! (prison staff 3)

Fear of safety

The interview rooms are full of brooms, irons, and chemicals, you don't feel safe when you're on your own with a prisoner (prison staff 4)

If you work on the wings all the time... then confrontation is always there in the back of your mind (prison staff 5)

Circle of stress

Various causes of stress—including reduced staffing levels, prison culture, prison management, and fear of safety—were frequently described as interacting with each other and increasing overall stress levels. This was best described by a member of the healthcare group who described a “circle of stress,” whereby low morale and staff shortages increased stress levels, which in turn increased staff sickness rates, reduced staffing levels, further lowered the morale of remaining staff and led to more stress and staff sickness (box 7).

Box 7: Circle of stress

... a fairly high level of sickness over all staff types over the last couple of years and at its worst it tends to have that snowballing effect, but because there are so many staff absent that those that are on duty are groaning under the strain because they're having to cope with more and more (prison staff 6)

Discussion

We have shown how wider environmental and organisational factors affect mental health within a prison setting. The qualitative data produced by this series of focus groups shows how long periods of being locked up with little activity or mental stimulation have a negative impact on the mental health of prisoners, whether or not they had a formal mental illness.

Recent reductions in staff levels created high levels of stress among staff, leading to a circle of stress whereby staff would be absent from work because of stress, causing more stress in remaining staff. Staff shortages led to longer lock-up times for prisoners and negatively affected their mental health, the ensuing frustration was released on staff, creating still higher stress levels (figure).

Similar findings on the reinforcement of stress are found in studies of other institutional settings. Organisations under stress can react with socially structured defence mechanisms that may lead to a dysfunctional system. For example, studies in hospitals showed that organisations with high anxiety levels reacted by avoidance of change, ritualisation of task performance, and upward delegation of responsibility. These behaviours occur to reduce anxiety but lead to inefficient working and subsequent increases in stress.18

Figure 1.

The circle of stress

These factors could be dealt with by reduced numbers of prisoners or by increased staff levels—for example, by the provision of occupational health to address high staff sickness levels and by improving staff communication, training, supervision, support, and teamworking. This would reduce the length of time prisoners are locked up and begin to alter the cultural environment within the prison, which in turn could have a significantly positive impact on prisoner mental health.

We used a “healthy settings approach” to guide the scope of this study. Our findings highlight the importance of using qualitative data to facilitate a wider understanding of factors affecting health.19 A prison is an ideal environment for incorporating a settings approach as it acts as a contained ecosystem with each area influencing the other.10 The process of using a settings approach for an assessment of health needs in prison led to the creation and acceptance of recommendations for the development of a health promoting prison.20 This approach can help in the development of health promoting policies, building of partnerships, increasing empowerment and ownership of change, and lead to structural and environmental improvements.21

Strengths and limitations

The main weakness of this study arises from the potential bias of using self selected volunteers for focus groups rather than a randomised sample.22 The people who attended the focus groups may therefore over-represent those prisoners and staff who have particular issues they want to raise.23 A greater proportion of female prisoners than male prisoners (13/90 (14%) v 17/500 (3.4%)) participated in the focus groups, potentially under-representing the views of male prisoners. However, we held several groups (three groups of male prisoners compared with one for females) and analysed areas of concordance within and across groups to reduce this bias.21 Additionally, we triangulated (compared results found from different sources to increase validity) views from staff focus groups on prisoner health with prisoners' views to produce a balanced and representative perspective of the mental health of prisoners.15,17

The results therefore give a reasonable representation of environmental factors affecting mental health within a UK prison. The prison studied is located in a relatively affluent part of the country, however, and comparisons have shown that it has better healthcare resources than many other prisons.24 Our findings therefore may under-represent the situation found in other prisons.

Implications

These findings may provide insight for clinicians and primary care trusts working in partnership to improve the mental health of prisoners. They may also inform and influence managers and policy makers of the wider contextual issues affecting mental health within prison settings. The current trend of increasing prisoner numbers can do nothing but worsen the environment within prisons with the resultant consequences on mental health. This situation is unlikely to benefit the long term rehabilitation of prisoners back into society.

Further similar research in other prisons could show how generalisable these findings are. Additionally, research is needed on which environmental adjustments positively influence the mental wellbeing of prisoners and prison staff.

The increasing numbers of prisoners with formal mental health problems3 should not be ignored, inappropriate incarceration should be avoided, and extra mental health services need to be provided. Recent Department of Health/Home Office policy states that from April 2003 prison primary healthcare services should be provided by primary care trusts and that the quality of health care in prisons should be monitored with the standards set by national service frameworks (including mental health).25,26 We have shown the necessity of understanding wider environmental factors that contribute to poor mental health and make mental illness worse in prisons. Health professionals have a role in advocating for better prison mental health services and in influencing policy affecting the prison environment, which in turn may lead to improvements in the mental health of prisoners.

What is already known on this topic

There is a high prevalence of mental health problems in prisoners and insufficient provision for these problems

Recent guidelines recommend that mental health services for prisons should be equivalent to those provided by the NHS

The link between environmental stress and mental ill health has been well established in several settings but not in prisons

What this study adds

Focus group discussions provided a complex understanding of environmental factors affecting prisoner mental health

Long periods of isolation with little mental stimulation in a remand prison contributed to intense frustration and anger and may influence the use of drugs to relieve tedium

In prison staff high levels of stress related to the prison organisation and environment negatively affected the mental health of prisoners and developed into a circle of stress

We thank all the prisoners and prison staff who participated in this study and acknowledge the openness and support given by the prison management in the process of improving health within their prison. We particularly thank Celia Grummitt, senior prison medical officer; Ruth Shakespeare, regional prison health task force lead; Gillian Spencer, consultant for public health, North and Mid Hampshire Health Authority; Katherine Weare, advanced courses coordinator/lecturer in health promotion, Research School of Education, University of Southampton; and John O'Grady, consultant in forensic psychiatry, Ravenswood Medium Secure Unit.

Contributors: JN had the idea for the study, planned the design and schedules, participated in the running of the focus groups, analysed the data, summarised the results, wrote the first draft of the paper, and is the guarantor. PW and JO both contributed in the planning stages, participated in running the focus groups, assisted in validating the data, reviewed drafts, and contributed to writing the paper.

Funding: North and Mid Hampshire Health Authority. The guarantor accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: We sought advice from the National Prison Health Task Force and local Health Authority Ethics Committee regarding ethical approval, and were informed that official approval was not needed as the primary aim of this study was for service improvement. We took all measures to conduct the study in an ethical manor.

References

- 1.Gunn J, Maden A, Swinton M. Treatment needs of prisoners with psychiatric disorders. BMJ 1991;303: 338-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooke D, Taylor C, Gunn J, Maden A. Point prevalence of mental disorder in unconvicted male prisoners in England and Wales. BMJ 1996;313: 1524-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birmingham L, Mason D, Grubin D. Prevalence of mental disorder in remand prisoners consecutive case study. BMJ 1996;313: 1521-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.HM Chief Inspector of Prisons for England and Wales. Suicide is everyone's concern: a thematic review. 1999. www.homeoffice.gov.uk/docs/suicide.html (accessed 23Nov 2002).

- 5.Department of Health. Our healthier nation. 1998. www.archive.official-documents.co.uk/document/doh/ohnation/title.htm (accessed 23 Nov 2002).

- 6.Office for National Statistics. Psychiatric morbidity among prisoners in England and Wales. 1997. www.statistics.gov.uk/ssd/surveys/ www.statistics.gov.uk/STATBASE/Product.asp?vlnk=2676 (accessed 21 Jul 2003).

- 7.Office of Population Censuses and Surveys. OPCS Morbidity Statistics from General Practice: Fourth National Study, 1991-1992. www.statistics.gov.uk (accessed 15 Oct 2002).

- 8.Department of Health. Making it happen: a guide to delivering mental health promotion. 2001. www.doh.gov.uk/mentalhealth/makingithappen.htm (accessed 23 Nov 2003).

- 9.Brown GW, Andrews B, Harris T, Alder Z, Bridge L. Social support, self-esteem and depression. Psychol Med 1986;16: 813-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. WHO health in prisons project. 2000. www.hipp-europe.org (accessed 19 Apr 2003).

- 11.Joint Prison Service/NHS Executive Working Group. Future organisation of prison health care. 1999. www.doh.gov.uk/nhsexec/prison.htm (accessed 15 Oct 2002).

- 12.Vaughn S, Shay Schumm J, Sinagub J. Focus group interviews in education and psychology. London: Sage, 1996.

- 13.Morgan DL. Focus groups as qualitative research. London: Sage, 1997.

- 14.Sim J. Collecting and analysing qualitative data: issues raised by the focus group. J Adv Nurs 1997;28: 345-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oppenheim AN. Questionnaire design, interviewing and attitude measurement. London: Pinter, 1992.

- 16.Cote-Arsenault D, Morrison-Beedy D. Practical advice for planning and conducting focus groups. Nurs Res 1999;48: 280-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brinberg D, McGrath. Validity and the research process. London: Sage, 1985.

- 18.Menzies Lyth I. Containing anxiety in institutions. London: Free Association Books, 1988.

- 19.Greenhalgh T. Integrating qualitative research into evidence based practice. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2002;31: 583-601, ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nurse J. Meeting the need: developing a prison health improvement programme. Basingstoke: North and Mid Hampshire Health Authority, 2000.

- 21.Whitelaw S, Baxendale A, Bryce C, Machardy L, Young I, Witney E. “Settings” based health promotion: a review. Health Prom Int 2001;16: 339-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in medicine. Boston: Little, Brown, 1987.

- 23.Reed J, Roskell V. Focus groups: issues of analysis and interpretation. J Adv Nurs 1997;26: 765-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.HM Prison Establishments. www.hmprisonservice.gov.uk/prisons (accessed 21 Jul 2003).

- 25.Department of Health. National service framework for mental health. 1999. www.doh.gov.uk/nsf/mentalhealth.htm (accessed 25 Nov 2002).

- 26.Department of Health. Prison health. www.doh.gov.uk/prisonhealth (accessed 25 Nov 2002).