Abstract

Aims

Voriconazole is a new triazole with broad-spectrum antifungal activity against clinically significant and emerging pathogens. These studies evaluated the pharmacokinetics and safety of intravenous voriconazole in healthy male volunteers.

Methods

Two single-blind, placebo-controlled studies were conducted. In Study A, 12 subjects were randomized to voriconazole (3 mg kg−1) or placebo, administered once daily on days 1 and 12, and every 12 h on days 3–11. In Study B, 18 subjects were randomized to voriconazole or placebo, with voriconazole being administered as a loading dose at 6 mg kg−1 twice on day 1, then at 3 mg kg−1 twice daily on days 2–9, and once at 3 mg kg−1 on day 10.

Results

In both studies, the plasma concentrations of voriconazole increased rapidly following the initiation of dosing. Minimum observed plasma concentration (Cmin) values at steady state were above the in vitro minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for most fungal pathogens (Cmin > 0.8 µg ml−1). The use of a loading dose in Study B resulted in a shorter time to steady-state Cmin values than was observed in Study A. Values of the final day plasma pharmacokinetic parameters in Studies A and B were similar: maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax) 3621 and 3063 ng ml−1; areas under the plasma concentration–time curve from time zero to the end of the dosing interval (AUCτ) 16 535 and 13 245 ng·h ml−1, and terminal elimination phase half-lives (t1/2) 6.5 and 6.7 h, respectively. On multiple dosing, voriconazole accumulated (AUCτ accumulation ratio 2.53–3.17, Study A) at a level that was not predictable from single-dose data. The mean concentration–time profiles for voriconazole in saliva were similar to those in plasma. Multiple doses of voriconazole were well tolerated and no subject discontinued from either study. Seven cases of possibly drug-related visual disturbance were reported in three subjects (Study B).

Conclusions

Administration of a loading dose of 6 mg kg−1 i.v. voriconazole on the first day of treatment followed by 3 mg kg−1 i.v. twice daily achieves steady state by the third day of dosing. This dosage regimen results in plasma levels of the drug that rapidly exceed the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) against important fungal pathogens, including Aspergillus spp.

Keywords: intravenous, pharmacokinetics, safety, tolerability, voriconazole

Introduction

Voriconazole is a new triazole antifungal agent, developed as oral and intravenous formulations, with potent activity against a broad spectrum of clinically significant pathogens, including Aspergillus and Candida spp. [1–3] and emerging pathogens, such as Scedosporium and Fusarium spp. [4, 5].

The two studies reported here were designed to investigate the pharmacokinetics, safety, and toleration of single- and multiple-dose intravenous voriconazole in healthy male volunteers. A dose of 3 mg kg−1 was selected based on anticipated maintenance doses for voriconazole. In addition, Study B also investigated the use of a 6-mg kg−1 twice daily i.v. loading dosing regimen, administered on day 1 only, to enable steady-state plasma concentrations to be achieved more rapidly.

Methods

Study subjects

Healthy male volunteers aged 18–45 years, weighing 60–90 kg with a body mass index of between 18 and 25 according to Quetelet's Index [weight(kg)/height2(m)] were eligible for inclusion in this study. Subjects were excluded if they had laboratory or physical abnormalities, or a history of clinically significant allergies, especially to medical treatments.

Study design

Two single-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials (Studies A and B) were performed. The study protocols were approved by independent ethics committees at the study sites (Leicester Clinical Research Centre, Evington, UK, and Besselaar Clinical Research Unit, Leeds, UK).

Study A

Twelve subjects were randomized in the ratio 3 : 1 to receive either voriconazole (3 mg kg−1) as an intravenous infusion (n = 9) or placebo (n = 3). The total volume of infusion was dependent on bodyweight, e.g. a 70-kg subject would receive a 105-ml infusion. On day 1, subjects received a single 1-h infusion of voriconazole or placebo at approximately 09.00 hours. On days 3–11 inclusive, they were given 1-h infusions of voriconazole or placebo, at approximately 09.00 and 21.00 hours. On day 12, subjects received a single 1-h infusion of voriconazole or placebo at approximately 09.00 hours.

Study B

Eighteen subjects were randomized in the ratio 1 : 1 to receive an initial intravenous infusion of either voriconazole (n = 9) or placebo (n = 9). On day 1, subjects received two 1-h infusions of voriconazole (6 mg kg−1) or placebo, separated by 12 h. On days 2–9, subjects were given 1-h infusions of voriconazole (3 mg kg−1) or placebo, separated by approximately 12 h (09.00 and 21.00 hours), and on day 10, they received a 1-h infusion of voriconazole (3 mg kg−1) or placebo in the morning.

Pharmacokinetic sampling

Venous blood samples (sufficient to provide 2.5 ml plasma) were taken (wherever possible from the contralateral arm to the infusion) into heparinized tubes. Blood samples were centrifuged at 4 °C within 30 min of collection, the plasma separated and stored at −20 °C, until analysed.

Study A

On days 1 and 12, blood samples were collected immediately before dosing, at frequent intervals for up to 12 h following the start of the infusion, and at 18, 24, 36, and 48 h. On days 5 and 8, samples were taken at frequent intervals for up to 12 h following the start of the morning infusion and immediately before the evening infusion. On days 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 11 they were taken before the morning dose only.

Study B

On day 1, blood samples were taken before the morning dose, at frequent intervals for up to 12 h following the start of the morning infusion, 1 h after the evening dose, and at 24 h. On days 3 and 6, samples were taken immediately before the morning dose and at frequent intervals for up to 12 h following the start of the morning infusion. On days 4, 5, 7, and 9, they were taken before the start of the morning infusion dose only. On day 10, samples were taken at frequent intervals for up to 12 h following the start of the final morning infusion, and at 18, 24, 36, and 48 h postdose.

Study A

Saliva samples (approximately 2 ml) were collected at intervals to correspond with blood samples, i.e. immediately before dosing and at frequent intervals up to 12 h following the start of the morning infusion on days 1 and 12. These samples were stored at −20 °C, until analysed. Saliva flow was stimulated with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tape.

Urine samples were collected over the 12-h period before dosing on day 1 (baseline), and on days 1 and 12 at 0–12, 12–24, 24–36, and 36–48 h after the dosing (timed from the start of the infusion). The total volume of the urine samples was recorded and 2 × 10-ml aliquots stored at −20 °C until analysed.

Voriconazole assay

Plasma, saliva, and urine samples were assayed using previously validated high-performance liquid chromatography assays with UV detection [6]. The assays for voriconazole in plasma, saliva, and urine were linear over the calibration ranges 10–3000 ng ml−1, 10–2000 ng ml−1, and 50–5000 ng ml−1, respectively. The corresponding lower limits of detection were 10 ng ml−1, 10 ng ml−1, and 50 ng ml−1.

For the assay of voriconazole in plasma, the interbatch imprecision, as assessed by the coefficients of variation of the means of quality control samples analysed together with the test samples, were 5.6%, 2.5%, and 6.3% at 25, 750, and 2500 ng ml−1, respectively, and the mean measured concentrations were 24 ng ml−1, 764 ng ml−1, and 2609 ng ml−1, representing relative errors of −3.8%, +1.8%, and +4.4%, respectively.

For the assay of voriconazole in saliva, the interbatch imprecision, as assessed by the coefficients of variation of the means of quality control samples analysed together with the test samples, were 6.1%, 4.4%, and 3.8% at 75, 500, and 1500 ng ml−1, respectively, and the mean measured concentrations were 79 ng ml−1, 522 ng ml−1, and 1561 ng ml−1, representing relative errors of +5.3%, +4.4%, and +4.1%.

For the assay of voriconazole in urine, the interbatch imprecision at the limit of quantification was satisfactory, as indicated by reverse calculated calibration data: coefficients of variation of the means of quality control samples analysed together with the test samples were <10%.

Safety assessments

All adverse events that occurred during treatment or up to 7 days after treatment were recorded. Where possible, information on the severity, time of onset, and duration of adverse events were recorded together with the investigator's assessment of their relationship to treatment. In addition, investigators were requested to report any serious adverse events occurring up to 30 days after the end of the study.

Routine clinical laboratory tests, haematology, and clinical chemistry were performed on blood samples taken at screening, and before the morning dose on days 1, 7, and 12, and at 48 h after final dose in Study A, and at screening, before the morning dose on days 1, 2, 6, 10, and at follow-up (2 weeks after final dose) in Study B. Creatinine clearance was estimated from the formula of Cockcroft and Gault [7]. In addition, standard dipstick urinalysis was performed in both studies.

The following renal function parameters were determined from 10-ml aliquots of timed urine collections: Study A, urinary N-acetyl-β-d-glucosamine (NAG) : creatinine ratio; Study B, NAG, creatinine, creatinine excretion rate, total protein, total protein excretion rate, microalbumin, microalbumin excretion rate, NAG : creatinine ratio, β2-microglobulin, β2-microglobulin : creatinine ratio.

In both studies, measurements of vital signs (supine and standing systolic and diastolic blood pressure and pulse rate) and a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) were performed at screening, before administration of the morning dose on day 1, prior to discharge, and at a follow-up visit. In addition, in Study A, 24-h Holter recording was performed at screening, and starting 30 min before administration of the morning dose on days 1, 7, and 12.

Pharmacokinetic parameters

The maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax) and the time to the first occurrence of Cmax (tmax) were obtained directly from the plasma concentration–time curves. Cmin was the minimum plasma concentration after multiple dosing. The area under the plasma concentration–time curve to the last sample time above the limit of quantification (AUCt), and from time zero (predose) until the end of the dosing interval (12 h) (AUCτ), were obtained by the linear trapezoidal rule. The area under the plasma concentration–time extrapolated to infinity (AUCinf) was calculated from AUCt + Ct/kel, where Ct is the concentration at the last sample time above the limit of quantification (days 1 and 12, Study A) and kel is the terminal elimination phase rate constant. kel was estimated by log-linear regression analysis (days 1 and 12) on those data points visually assessed to be on the terminal log-linear phase. The systemic clearance (CLp) was calculated as the dose/AUC (day 1, Study A) or the dose/AUCτ (day 12, Study A or day 10, Study B). The terminal elimination phase half-life (t1/2) was calculated as 0.693/kel. The apparent volume of distribution at steady state (Vss) on day 1 was calculated as (CLp × MRT–T/2) where MRT is the mean residence time and T is the duration of infusion. At other time points Vss was estimated from the CLp/AUC at appropriate times and the t1/2. The extent of accumulation during the dosing periods was assessed by comparing Cmax and AUCτ on days 5, 8, and 12 with the corresponding values on day 1 (Study A). The linearity ratio (Study A) was calculated from AUCτ(multiple dose)/AUC(day 1) for days 5, 8, and 12. Renal clearance (CLr) was calculated as Ae/AUCt, where Ae is the total amount of unchanged drug excreted in the urine up to time t. The Cmax for saliva was the concentration at the end of the infusion, and the AUCτ for saliva was the area under the saliva concentration–time curve within a dosage interval.

Statistical analysis

Formal statistical analyses were performed on data from Study A but not Study B. In Study A, natural log-transformed Cmax and AUCτ, and untransformed kel values derived from plasma samples were subjected to an analysis of variance (anova) which allowed for variation due to subjects and days. A two-sided significance level of 5% was used to indicate evidence of differences in pharmacokinetic parameters with time (day 1/day 12). They were derived from the F-test based on an appropriate model term in the anova. The residual and fitted values from the anova were examined graphically to ensure that the underlying assumptions of normality and equal variances were met, and that there were no outlying data values exerting undue influence on the results. All analyses and tabulations were performed using SAS/STAT® (SAS Institute Inc., North Carolina, USA) software [8]. Formal statistical analyses of data derived from saliva and urine samples were not performed.

Results

Subject demographics

The demographic characteristics of the 30 subjects who entered the two studies are shown in Table 1. In both studies, subjects who received voriconazole or placebo were comparable. All subjects were included in the safety evaluation, and all subjects who received voriconazole were included in the pharmacokinetic analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics of all randomized subjects.

| Study A | Study B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voriconazole | Placebo | Voriconazole | Placebo | |

| Number of subjects | 9 | 3 | 9 | 9 |

| Mean age in years (range) | 24 (20–31) | 21 (19–23) | 28 (19–41) | 28 (21–39) |

| Mean weight in kg (range) | 72 (60–87) | 68 (60–80) | 73 (66–80) | 71 (63–77) |

| Mean height in cm (range) | 176 (167–186) | 176 (169–182) | 179 (172–185) | 179 (166–190) |

Pharmacokinetics

Study A

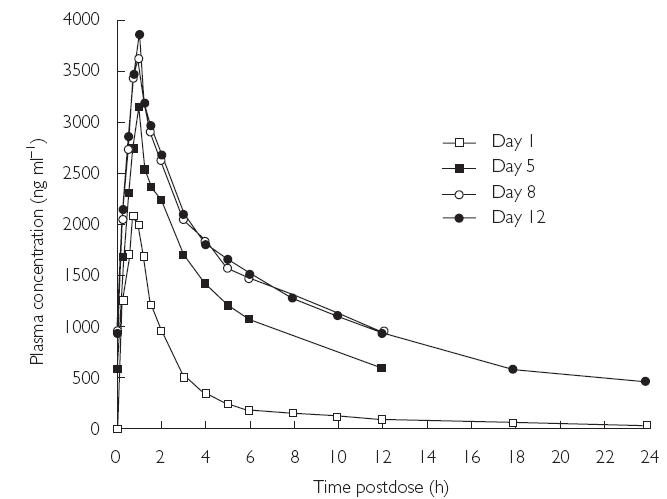

The mean plasma concentration–time profiles of voriconazole for days 1, 5, 8, and 12 are shown in Figure 1. Plasma concentrations of voriconazole increased rapidly following the initiation of treatment and maximum levels generally occurred at the end of the 1-h infusion. Thereafter, they declined rapidly in a biphasic manner, with evidence of a distribution phase.

Figure 1.

Mean plasma concentration–time profiles of voriconazole for days 1, 5, 8, and 12 (Study A)

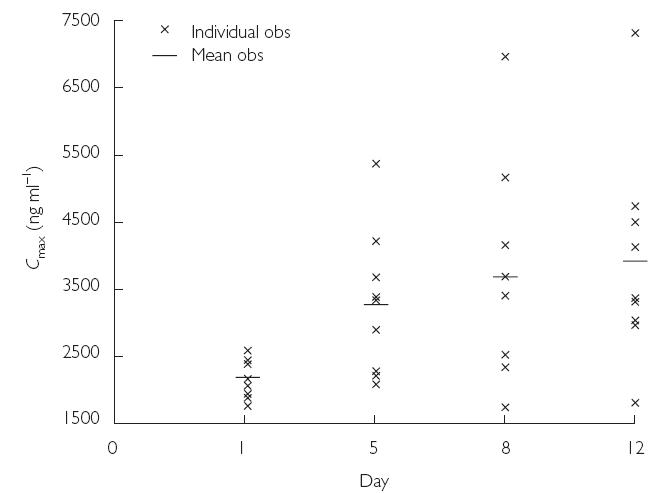

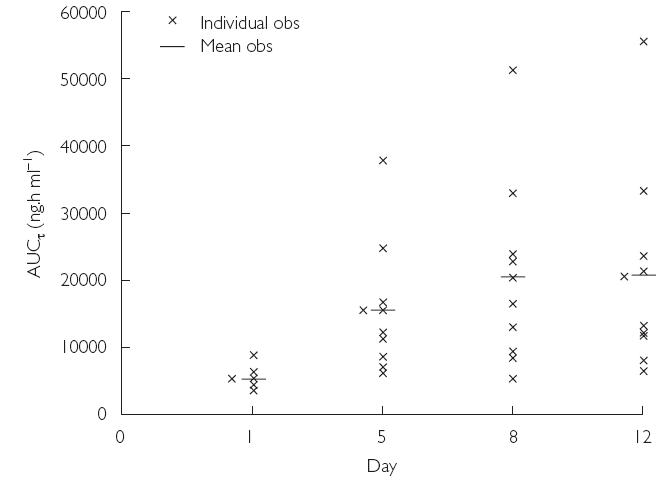

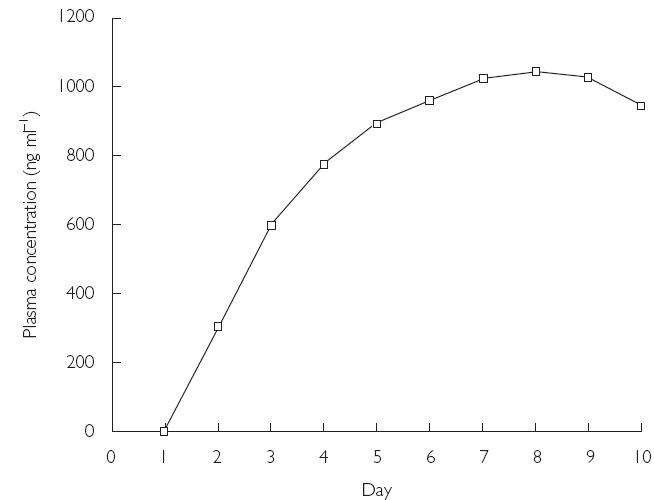

The mean values of the pharmacokinetic parameters for voriconazole in plasma following the administration of a single dose (day 1), during multiple dosing (days 5 and 8), and at the end of multiple dosing (day 12) are shown in Table 2. The mean values of AUCτ and Cmax for days 1, 5, 8, and 12 demonstrated accumulation of voriconazole on multiple dosing. Compared with day 1, there was greater intersubject variation in Cmax and AUCτ values on days 5, 8, and 12 (Figures 2 and 3). The mean accumulation ratios for AUCτ and Cmax were similar on days 8 and 12, compared with day 1, but were slightly lower for day 5 compared with day 1. The calculated linearity ratios (AUCτ(multiple dose)/AUCinf(single dose)) were >1 and exhibited considerable intersubject variation (Table 3). Voriconazole appeared to reach steady state in plasma between day 5 and day 8, since the difference in values for both Cmax and AUCτ was statistically significant between day 12 and day 1 (Table 2, P < 0.001), but was not significantly different at the 5% level between day 8 and day 5, or between day 12 and day 8. The mean plasma voriconazole Cmin values over the multiple-dosing period are shown in Figure 4.

Table 2.

Summary of mean pharmacokinetic parameters for voriconazole in plasma (Study A).

| Parameter | Day 1 | Day 5 | Day 8 | Day 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng ml−1)* | 2135 | 3097 | 3420 | 3621 |

| AUCτ (ng·h ml−1)* | 5215 | 13 210 | 16 381 | 16 535 |

| AUC (ng·h ml−1)* | 6023 | – | – | 23 571 |

| AUCt (ng·h ml−1)* | 5858 | – | – | 22 723 |

| tmax (h)† | 0.83 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| CLp (ml min−1 kg−1)* | 8.3 | – | – | 3.0 |

| Vss (l kg−1)† | 2.2 | – | – | 1.5 |

| kel (h−1)† | 0.124 | – | – | 0.107 |

| t1/2 (h)‡ | 5.6 | – | – | 6.5§ |

Geometric mean.

Arithmetic mean.

Harmonic mean.

Includes data from one subject who had t1/2 = 21.7 h.

Figure 2.

Mean and individual plasma Cmax values for voriconazole on days 1, 5, 8, and 12 (Study A)

Figure 3.

Mean and individual plasma AUCτ values for voriconazole on days 1, 5, 8, and 12 (Study A)

Table 3.

Mean accumulation and linearity ratios from Study A

| Mean accumulation ratio* | Mean linearity ratio* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AUCτ | Cmax | AUCτ(multiple dose)/AUCinf(single dose) | |

| Day 5/day 1 | 2.53 | 1.45 | 2.19 |

| Day 8/day 1 | 3.14 | 1.60 | 2.72 |

| Day 12/day 1 | 3.17 | 1.70 | 2.75 |

Geometric mean.

Figure 4.

Mean plasma Cmin values for voriconazole for the first to the tenth day of multiple dosing (days 1, 5, 8, and 12; Study A).

The difference in the kel between day 1 and day 12 was not statistically different (P = 0.111), and the mean t1/2 were similar (5.6 and 6.5 h for days 1 and 12, respectively, Table 2). The mean value of the t1/2 for day 12 was influenced by an unusually high t1/2 of 21.7 h recorded in one subject receiving voriconazole. A higher Cmax value after multiple dosing, and higher AUCτ values and lower CLp values after both single and multiple dosing, were also observed in this subject.

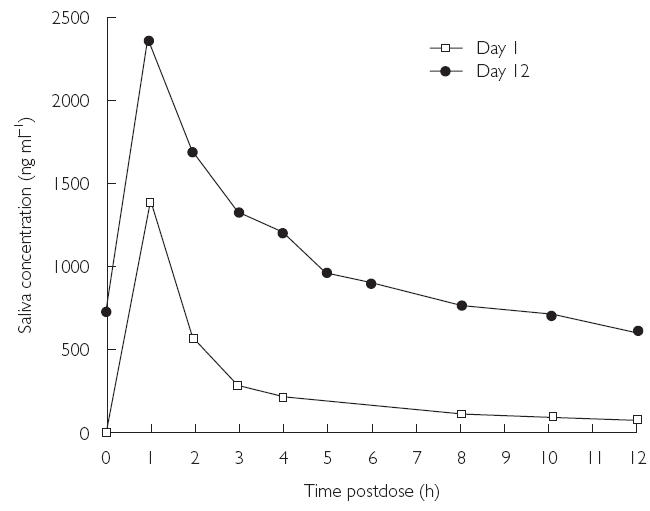

The mean saliva concentration–time profiles of voriconazole for days 1 and 12 are shown in Figure 5. These showed a similar pattern to those for plasma. The mean Cmax, AUCτ, and tmax values for days 1 and 12 are shown in Table 4.

Figure 5.

Mean saliva concentration–time profiles of voriconazole for days 1 and 12 (Study A)

Table 4.

Summary of mean pharmacokinetic parameters for voriconazole in saliva (Study A)

Geometric mean.

Arithmetic mean.

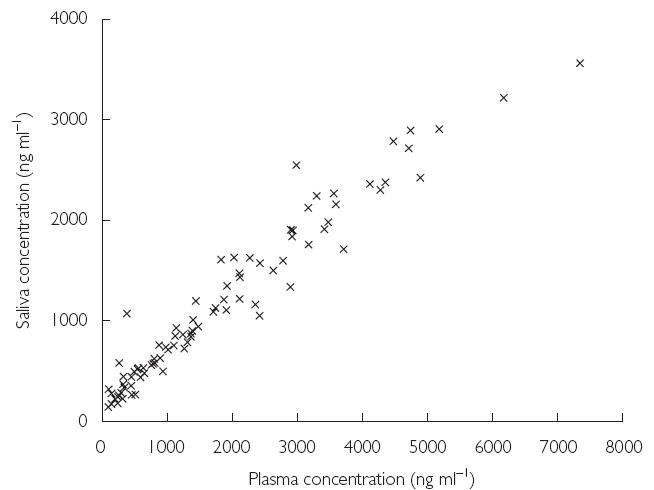

The saliva accumulation ratios (day 12 : day 1) were very similar to those for plasma. The mean ratio for Cmax was 1.67 (compared with 1.70 for plasma Cmax), and the mean ratio for AUCτ was 3.40 (3.17 for plasma). Saliva to plasma ratios for AUCτ were similar for days 1 and 12 (0.62 vs. 0.66) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Relationship between mean plasma and mean saliva concentration of voriconazole at steady state (day 12; Study A). All concentrations are plotted with no indication of time postdose at which they were measured

Study B

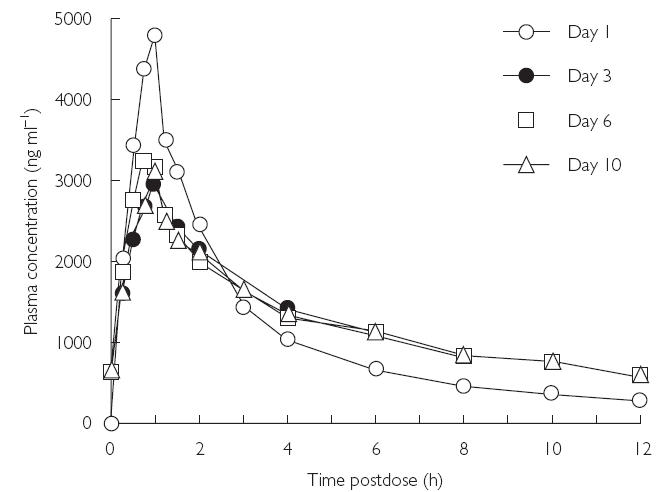

The mean plasma concentration–time profiles of voriconazole for days 1, 3, 6, and 10 are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Mean plasma concentration–time profiles of voriconazole for days 1, 3, 6, and 10 (Study B)

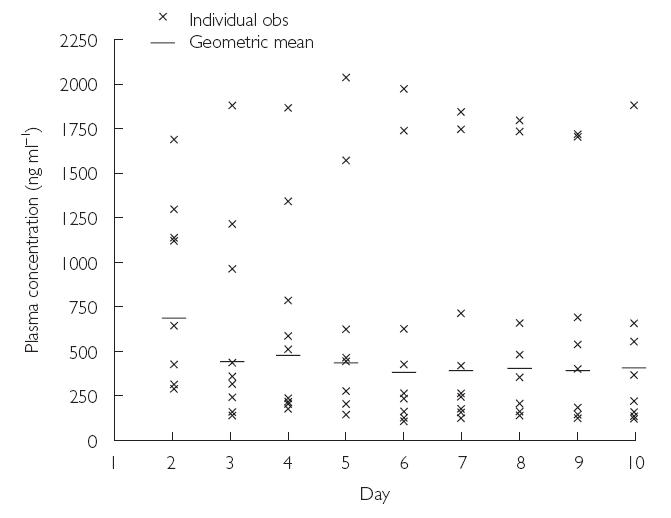

Plasma levels increased rapidly and maximum concentrations occurred at the end of the infusion in the majority of subjects. Plasma concentrations then declined rapidly in a biphasic manner and the distribution phase was complete by approximately 4 h postdose (relative to the start of the infusion). Visual inspection of Cmin data suggested that steady state was reached on day 3 (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Mean and individual plasma Cmin values for voriconazole for the first to the tenth day of multiple dosing (Study B)

The mean values of the pharmacokinetic parameters for voriconazole in plasma are shown in Table 5. After administration of voriconazole at 6 mg kg−1 on day 1, Cmax was 4695 ng ml−1 and AUCτ was 13 217 ng·h ml−1. Steady-state values on day 3 were: Cmax 3031 ng ml−1, and AUCτ 13 584 ng·h ml−1. Cmax values were similar between days 3, 6, and 10, and AUCτ values were similar between days 1, 3, 6, and 10, despite the dose on day 1 being double those on days 3, 6, and 10.

Table 5.

Summary of mean pharmacokinetic parameters for voriconazole in plasma (Study B).

| Parameter | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 6 | Day 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cinf (ng ml−1)* | 4675 | 2891 | 3141 | 2983 |

| Cmax (ng ml−1)* | 4695 | 3031 | 3150 | 3063 |

| Cmin (ng ml−1)* | – | 456 | 389 | 420 |

| AUCτ (ng·h ml−1)* | 13 217 | 13 584 | 12 928 | 13 245 |

| tmax (h)† | 0.94 | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.06 |

| CLp (ml min−1 kg−1)* | – | – | – | 3.8 |

| Vss (l kg−1)† | – | – | – | 1.6 |

| kel (h−1)† | – | – | – | 0.1038 |

| t1/2 (h)‡ | – | – | – | 6.7 |

Geometric mean.

Arithmetic mean.

Harmonic mean.

The mean accumulation ratios for AUCτ and Cmax on days 3, 6, and 10, compared with the corresponding values on day 1, were similar, and ranged from 2.0 to 2.3, and 1.3 to 1.4, respectively. On day 10, the t1/2 was 6.7 h, the CLp was 4.2 ml min−1 kg−1, and the Vss was 1.6 l kg−1. Coefficients of variation showed a high degree of variability for Cmin, AUCτ, and CLp on multiple dosing, with values of approximately 100%, 60%, and 47%, respectively.

The pharmacokinetics parameters for the final day of dosing in the two studies were comparable.

Adverse events

Study A

All nine of the subjects receiving voriconazole, and three subjects in the placebo group, experienced 21 and eight treatment-emergent adverse events, respectively. In the voriconazole group, one subject each experienced mild postural hypotension, mild sweating and moderate peripheral oedema, and two subjects experienced mild headache. The other adverse events in this group were associated with the injection site, such as local oedema, inflammation or pain, and all were mild in nature. There were no discontinuations due to adverse events. Only one case of headache, and the adverse events associated with the injection site, were considered by the investigator to be possibly related to treatment. The subject who experienced an unusually long exposure to voriconazole (t1/2 = 21.7 h) had a similar adverse event profile to all other subjects.

No clinical laboratory test abnormalities were reported and the median changes from baseline in clinical laboratory data did not identify any patterns that indicated a correlation with voriconazole administration. The mean changes in baseline urinary creatinine, NAG, and the NAG : creatinine ratio did not point to any treatment-related effects. The mean changes from baseline in supine and standing blood pressures and pulse rates were not clinically significant and did not show any pattern to suggest a relationship with voriconazole administration. There were no clinically significant changes in ECG data (heart rate, QT interval, PR interval, QRS interval), and there were no abnormalities recorded on the Holter monitor for subjects who received voriconazole, whereas two subjects administered placebo had abnormalities that were not considered to be clinically significant.

Study B

Eight subjects who received voriconazole and eight subjects in the placebo group experienced 29 and 18 treatment-emergent adverse events, respectively. Many of these adverse events were associated with the injection site. Excepting adverse events associated with the injection site, in the voriconazole group there was one case each of postural hypotension, vasodilatation, constipation, nausea, tooth disorder, ulcerative stomatitis, somnolence, respiratory disorder, skin disorder, arthralgia, and abnormal vision, and two cases each of ecchymosis, dizziness, and photophobia. All of these, except one case of moderate arthralgia, were mild. Adverse events were considered to be possibly related to voriconazole in only three subjects: five reports of mild photophobia from two subjects, and two reports of mild abnormal vision from one subject. These occurred within 30 min of the start of the infusion only on days 1 and 2 (prior to reaching steady-state conditions), and were not reported thereafter. The median duration of these visual disturbances was 47 min (range 15–73 min) and all resolved without treatment. There were no reports of visual disturbances in the placebo group.

No clinically significant laboratory test abnormalities were observed in either treatment group. One subject who received voriconazole had an elevated eosinophil count but this was considered to be not clinically significant and not related to the study drug. No clinically significant or treatment-related changes in blood pressure, pulse rate, or ECG data (heart rate, QT interval, PR interval, QRS interval), were observed. Similarly, no clinically significant or treatment-related changes in renal function were observed.

Discussion

The pharmacokinetics, safety, and toleration of intravenous voriconazole have been evaluated in two studies in healthy male volunteers.

Maximum plasma voriconazole concentrations were generally observed at the end of the infusion period and these subsequently declined in a biphasic manner, with evidence of a distribution phase. The pharmacokinetic data from both studies suggested that voriconazole exhibits nonlinear kinetics, and there was accumulation of the drug in plasma with multiple dosing. The accumulation of voriconazole was shown in Study A to be associated with an apparent reduction in CLp and Vss. The predicted accumulation for a compound with linear kinetics was lower (1.16) than the actual accumulation values observed in Study A. In addition, the calculated mean linearity ratios (AUCτ(multiple dose)/AUCinf(single dose)) on days 5, 8, and 12 were >1, further indicating that voriconazole exhibited nonlinear pharmacokinetics.

The steady-state pharmacokinetic data were similar in the two studies. In Study A, the plot of the mean plasma Cmin values over the multiple dosing period (Figure 4), and visual inspection of the data from the individual subjects, indicated that steady state was achieved between day 5 and day 8 (corresponding to days 3 and 6, respectively, of the twice-daily dosing regimen).

In Study B, the use of a loading dose (two 1-h infusions every 12 h) on day 1 resulted in steady state being achieved on day 3, that is 1 day after the switch to 3 mg kg−1 twice daily.

When a loading dose was used (Study B), a high initial plasma Cmax was achieved, and the mean day 1 Cmin value in plasma was still above the in vitro minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values for voriconazole for Aspergillus spp. (< 0.5 µg ml−1), Candida spp. (0.06–0.5 µg ml−1), Cryptococcus neoformans (< 0.03 µg ml−1), and for many of the emerging fungal pathogens [9]. In the absence of a loading dose (Study A), the mean day 1 Cmin value was below the therapeutic threshold for many common fungal pathogens, whereas, in both studies, the mean steady-state Cmin values were above the MIC values. These findings suggest therefore that intravenous voriconazole given as a loading dose on day 1 followed by 3 mg kg−1 twice daily, will provide effective therapy for patients with fungal infections that are outside the spectrum of activity of many antifungal agents, such as those caused by Aspergillus spp.

The pharmacokinetic data for saliva show a similar pattern to that observed for plasma. Maximum concentrations of voriconazole in saliva were obtained at the end of infusion and thereafter declined in a biphasic manner. The concentration of voriconazole in saliva was approximately 65% of that in plasma, which is consistent with plasma protein binding of 58%. The ratio of saliva concentrations to plasma concentrations remained similar over time in most individuals, suggesting that voriconazole concentrations in saliva samples may be predictive of those in the plasma. Less than 1.5% of the administered dose of voriconazole was excreted unchanged in the urine during single and multiple dosing. Thus, renal elimination is not the major route of excretion of the drug after intravenous dosing.

Multiple doses of voriconazole were well tolerated in these studies. No serious adverse events were reported and no subject discontinued from either study. Although visual adverse events were frequent in subjects receiving voriconazole in Study B, they were all classified as mild in nature, were transient, and resolved spontaneously. No subject discontinued treatment because of visual adverse events. These data are comparable to those reported in a previous study in which visual function tests indicated that the visual disturbances were not associated with any clinical abnormality [10]. There were no clinically significant or treatment-related changes in laboratory safety tests, renal function, vital signs, or in ECG parameters during the two studies.

Administration of a loading dose of 6 mg kg−1 voriconazole on the first day of treatment followed by 3 mg kg−1 twice daily achieves steady state by the third day of dosing. This dosage regimen results in plasma levels of the drug that rapidly exceed the MICs against important fungal pathogens, including Aspergillus spp., an important factor in such critically ill patients. The efficacy and safety of voriconazole is currently being evaluated in Phase III clinical trials.

References

- 1.Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Mellado E, Martinez-Suarez JV, Monzon A. Comparison of the in vitro activity of voriconazole (UK-109,496), itraconazole and amphotericin B against clinical isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:531–533. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Espinel-Ingroff A. In vitro activity of the new triazole voriconazole (UK-109496) against opportunistic filamentous and dimorphic fungi and common and emerging yeast pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:198–202. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.198-202.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandrasekar PH, Manavathu E. Voriconazole: a second-generation triazole. Drugs Today. 2001;37:135–148. doi: 10.1358/dot.2001.37.2.614849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torre-Cisneros J, Gonzalez-Ruiz A, Hodges MR, Lutsar I. Voriconazole (VORI) for the treatment of S. apiospermum and S. prolificans infection. Program and Abstracts of the 38th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America; New Orleans, LA. 2000. Abstract 305, September. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perfect J, Gonzalez-Ruiz A, Lutsar I. Program and Abstracts of the 38th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. New Orleans, LA: 2000. Voriconazole (VORI) for the treatment of resistant and rare fungal pathogens. Abstract 303, September. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stopher DA, Gage R. Determination of a new antifungal agent, voriconazole, by multidimensional high-performance liquid chromatography with direct plasma injection onto a size-exclusion column. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1997;691:441–448. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(96)00408-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.SAS/STAT user's guide. 4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1989. Version 6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verweij PE, de Pauw BE, Meis JF. Voriconazole. Curr Opin Anti-Infect Invest Drugs. 1999;1:361–372. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purkins L, Wood N, Ghahramani P, Greenhalgh K, Allen MJ, Kleinermans D. Pharmacokinetics and safety of voriconazole following intravenous to oral dose escalation regimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2546–2553. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.8.2546-2553.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]