Abstract

Aims

Our aim was to investigate the effects of rifampicin on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nateglinide, a novel short-acting antidiabetic drug.

Methods

In a randomized crossover study with two phases, 10 healthy volunteers took 600 mg rifampicin or placebo orally once daily for 5 days. On day 6 of both phases, they ingested a single 60 mg dose of nateglinide. Plasma nateglinide and blood glucose concentrations were measured for up to 7 h postdose.

Results

Rifampicin decreased the mean AUC(0,7 h) of nateglinide by 24% (range 5–53%; P = 0.0009) and shortened its half-life (t1/2) from 1.6 to 1.3 h (P = 0.001). However, the peak plasma nateglinide concentration (Cmax) remained unchanged. The AUC(0,7 h) of the M7 metabolite of nateglinide was decreased by 19% (P = 0.002) and its t1/2 was shortened from 2.1 to 1.6 h by rifampicin (P = 0.008). Rifampicin had no significant effect on the blood glucose-lowering effect of nateglinide.

Conclusions

Rifampicin modestly decreased the plasma concentrations of nateglinide probably by inducing its oxidative biotransformation. In some patients, rifampicin may reduce the blood glucose-lowering effect of nateglinide.

Keywords: drug interaction, nateglinide, rifampicin

Introduction

Nateglinide is a new rapid- and short-acting antidiabetic drug of the meglitinide analogue class [1]. Its oral bioavailability is about 70% and its peak plasma concentrations are reached in about 1 h. Nateglinide is eliminated primarily by oxidative biotransformation, with only about 15% of the dose being excreted unchanged. The elimination half-life (t1/2) of nateglinide is about 1.5 h. The enzymes involved in its biotransformation have not yet been fully characterized, but cytochromes P450 (CYP) 2C9 and 3A4 contribute to nateglinide metabolism in vitro[2, 3]. Fluconazole (400 mg on day 1 and 200 mg on days 2–4), an inhibitor of CYP2C9 [4], CYP2C19 [5] and CYP3A4 [6], increased the AUC(0,∞) of nateglinide by 48% and impaired the formation of the M7 (a dehydro derivative) metabolite of nateglinide [7].

The rifamycin antibiotic rifampicin is a potent inducer of several drug-metabolizing enzymes [8], including CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 [9–11], and of some drug transporters [12, 13]. Therefore it decreases the plasma concentrations and effects of several antidiabetic drugs, such as the meglitinide analogue repaglinide, and the sulphonylureas [14–17]. We have studied the effects of rifampicin on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nateglinide.

Methods

Subjects

Ten healthy male volunteers (age range 19–39 years; weight range 61–97 kg) participated in the study after giving written informed consent. They were ascertained to be healthy by medical history, physical examination and routine laboratory tests before they were entered in the study. None was a tobacco smoker or used any continuous medication.

Study design

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Studies in Healthy Subjects and Primary Care of the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District and by the National Agency for Medicines. A randomized crossover study with two phases and a washout period of 4 weeks was carried out. The volunteers took 600 mg rifampicin (Rimapen 600 mg tablet, Orion Pharma, Espoo, Finland) or placebo orally once daily at 20.00 h for 5 days. After an overnight fast at 09.00 h on day 6, a single oral dose of 60 mg nateglinide (Starlix 60 mg tablet, Novartis Europharm Limited, Horsham, UK) was administered with 150 ml water. The volunteers remained seated for the next 3 h. A standardized light breakfast was served precisely 15 min after the administration of nateglinide, a standardized warm meal was served after 3 h and a standardized light meal was served after 7 h. The breakfast was eaten within 10 min and contained approximately 370 kcal energy, 70 g carbohydrates, 8 g protein and 6 g fat. Food intake was identical during both days of nateglinide administration. The subjects were under direct medical supervision on the days of administration of nateglinide. Glucose for intravenous use and glucagon for intramuscular use were available in case of severe hypoglycaemia, but they were not needed.

Blood sampling and determination of blood glucose concentrations

On the days of administration of nateglinide, a forearm vein of each subject was cannulated and was kept patent with a stylet. Timed blood samples were drawn before the administration of nateglinide and 15, 30, 45, 60, 75 and 90 min and 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 5 and 7 h later. The blood samples (10 ml each) were transfered into tubes that contained ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Blood glucose concentrations were measured immediately after sampling by the glucose oxidase method with the Precision G Blood Glucose Testing System (Medisense, Bedford, Mass, USA). Plasma was separated within 30 min after blood sampling and the samples were stored at −70 °C until analysis. The between-day coefficient of variation (CV) for blood glucose analysis was 6.8% at 2.8 mmol l−1, 0.0% at 5.2 mmol l−1 and 0.7% at 16.6 mmol l−1 (n = 4).

Determination of plasma nateglinide concentrations

Plasma nateglinide and its M7 metabolite (a dehydro derivative) concentrations were measured using the liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometer PE SCIEX API 3000 (Sciex Division of MDS Inc, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) in the atmospheric pressure chemical ionization mode [2]. Repaglinide served as the internal standard. The ion transitions monitored were m/z 318–166 for nateglinide, m/z 316–166 for M7 and m/z 453–230 for repaglinide. These transitions represent the product ions of the [M + H]+ ions. The quantification limit for nateglinide was 0.5 ng ml−1 and the between-day CV was 6.8% at 20 ng ml−1, 11.0% at 200 ng ml−1 and 7.2% at 1600 ng ml−1 (n = 4). M7 is given in arbitrary units relative to the ratio of the peak height of M7 to that of the internal standard in the chromatogram of the [M + H]+ ions.

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics of nateglinide and M7 were characterized by peak concentration in plasma (Cmax), time to Cmax (tmax), areas under the concentration-time curve [AUC(0,7 h) and AUC(0,∞)] and elimination half-life (t1/2). The terminal log-linear part of the concentration-time curve was identified visually for each subject. The elimination rate constant (kel) was determined by linear regression analysis of the log-linear part of the plasma drug concentration-time curve (using 3–6 data points). The t1/2 was calculated by the equation t1/2= ln2/kel. The AUC values were calculated by use of the linear trapezoidal rule for the rising phase of the plasma drug concentration-time curve and the log-linear trapezoidal rule for the descending phase, with extrapolation to infinity, when appropriate, by dividing the last measured concentration by kel.

Pharmacodynamics

The pharmacodynamic response to nateglinide was characterized by the mean change, maximum increase and maximum decrease in blood glucose concentration. The mean change was calculated by dividing the net area under the blood glucose concentration-time curve from 0 to 3 h and 0–7 h by the corresponding time interval.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean values ± SD in the text and tables and, for clarity, as mean values ± SEM in the figures. For all variables except tmax, 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated on the mean differences between the placebo and rifampicin phases. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic variables after the two pretreatments were compared with a paired t-test or, in the case of tmax, by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. All the data were analysed with the statistical program Systat for Windows, version 6.0.1 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill, USA). The differences were considered statistically significant at a P value of less than 0.05.

Results

Pharmacokinetics of nateglinide

Rifampicin significantly decreased the plasma concentrations of both nateglinide and its M7 metabolite (Table 1 and Figure 1). The mean AUC(0,7 h) of nateglinide declined by 24% (range 5–53%; P = 0.0009). Rifampicin had no significant effect on the mean Cmax of nateglinide (Figure 2). In subject 2, the absorption of nateglinide seemed to be markedly reduced during the rifampicin phase and its kel and that of M7 could not be determined because of apparent flip-flop kinetics. In the remaining nine subjects, rifampicin decreased the mean AUC(0,∞) of nateglinide by 22% (range 6–34%; P = 0.00004) and shortened its t1/2 from 1.6 to 1.3 h (P = 0.001). Rifampicin also reduced the AUC(0,∞) of M7 by 22% (P = 0.004) and shortened its t1/2 from 2.1 to 1.6 h (P = 0.008).

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for nateglinide (60 mg) in 10 healthy volunteers after a 5-day treatment with 600 mg rifampicin or placebo once daily.

| Variable | Placebo phase (control) | Rifampicin phase | Mean difference between placebo and rifampicin (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nateglinide | ||||

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 4934 ± 1263 | 3931 ± 1310 | 1003 (−545, 2551) | 0.18 |

| % of control (range) | 100% | 80% (18–169%) | ||

| tmax (min) | 37.5 (30–60) | 30 (30–60) | 0.74 | |

| t1/2 (h)* | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 0.3 (0.1, 0.4) | 0.001 |

| % of control (range) | 100% | 84% (74–92%) | ||

| AUC(0,7 h) (ng ml−1 h) | 7161 ± 980 | 5448 ± 1213 | 1714 (914, 2513) | 0.0009 |

| % of control (range) | 100% | 76% (47%-95%) | ||

| AUC(0,∞) (ng ml−1 h)* | 7310 ± 1044 | 5734 ± 1206 | 1576 (1121, 2031) | 0.00004 |

| % of control (range) | 100% | 78% (66–94%) | ||

| M7 | ||||

| Cmax (U ml−1) | 198 ± 37 | 192 ± 48 | 7 (−30, 43) | 0.68 |

| % of control (range) | 100% | 97% (40–155%) | ||

| tmax (min) | 60 (45–90) | 60 (45–120) | 0.44 | |

| t1/2 (h)* | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.4 (0.1, 0.7) | 0.008 |

| % of control (range) | 100% | 79% (61–102%) | ||

| AUC(0,7 h) (U ml−1 h) | 542 ± 71 | 440 ± 69 | 102 (47, 158) | 0.002 |

| % of control (range) | 100% | 81% (61%-108%) | ||

| AUC(0,∞) (U ml−1 h)* | 623 ± 106 | 486 ± 60 | 137 (58, 216) | 0.004 |

| % of control (range) | 100% | 78% (62–102%) | ||

| M7/nateglinide ratio | ||||

| Cmax (U ng−1) | 0.0416 ± 0.00825 | 0.0510 ± 0.00976 | −0.0094 (−0.0204, 0.0016) | 0.08 |

| AUC(0,7 h) (U ng−1) | 0.0768 ± 0.0128 | 0.0821 ± 0.0110 | −0.0053 (−0.0150, 0.0044) | 0.25 |

| AUC(0,∞) (U ng−1)* | 0.0861 ± 0.0151 | 0.0864 ± 0.0118 | 0.0000 (−0.0002, 0.0002) | 0.96 |

Data are mean values (± SD); tmax data are given as median (range).

Because of delayed absorption of nateglinide, the kel of nateglinide and M7 could not be determined for subject 2 in the rifampicin phase; the t1/2 and AUC(0, ∞) data are from the other nine subjects.

Figure 1.

Mean (± SEM) plasma concentrations of nateglinide (a) and its M7 metabolite (b) in 10 healthy volunteers following a single oral dose of 60 mg nateglinide after 5 days treatment with placebo (○) or 600 mg rifampicin (•) once daily. Insets depict the same data on a semilogarithmic scale.

Figure 2.

Individual Cmax (a) and AUC(0,7 h) (b) values of nateglinide in 10 healthy volunteers following a single oral dose of 60 mg nateglinide after 5 days treatment with placebo or 600 mg rifampicin once daily.

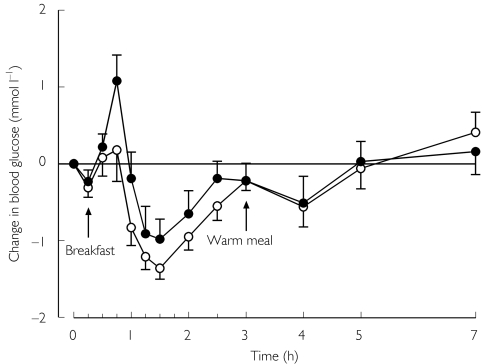

Pharmacodynamics of nateglinide

No significant differences were seen in the blood glucose response to nateglinide between the phases (Table 2 and Figure 3). No subject experienced symptomatic hypoglycaemia.

Table 2.

Blood glucose response to 60 mg nateglinide followed by a breakfast after 15 min and a warm meal after 3 h in 10 healthy volunteers after a 5 day treatment with 600 mg rifampicin or placebo once daily.

| Blood glucose variable | Placebo phase (control) | Rifampicin phase | Mean difference between placebo and rifampicin (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean change 0,3 h (mmol l−1) (range) | −0.6 ± 0.3 (−1.0 to −0.1) | −0.3 ± 0.7 (−1.6–0.5) | −0.3 (−0.9, 0.2) | 0.20 |

| Mean change 0,7 h (mmol l−1) (range) | −0.3 ± 0.5 (−1.2–0.2) | −0.2 ± 0.7 (−1.5–0.9) | −0.1 (−0.7, 0.4) | 0.61 |

| Maximum increase (mmol l−1) (range) | 0.9 ± 0.8 (0.0–2.8) | 1.1 ± 1.0 (0.9–2.6) | −0.2 (−0.8, 0.4) | 0.48 |

| Maximum decrease (mmol l−1) (range) | 1.7 ± 0.4 (0.7–2.2) | 1.5 ± 0.6 (0.9 to 2.6) | 0.2 (−0.4, 0.9) | 0.43 |

Data are mean values (±SD).

Figure 3.

Mean (± SEM) change in blood glucose concentrations in 10 healthy volunteers following a single oral dose of 60 mg nateglinide after 5 days treatment with placebo (○) or 600 mg rifampicin (•) once daily.

Discussion

The present results indicate that rifampicin can decrease the plasma concentrations of nateglinide and its M7 metabolite. There was marked interindividual variation in the effects of rifampicin on nateglinide pharmacokinetics with the reduction in the AUC(0,7 h) of the drug ranging from 5% to 53%. However, rifampicin had no significant effect on the blood glucose-lowering effect of nateglinide.

Nateglinide has low lipophilicity and it has been suggested to be actively transported by an intestinal uptake transporter that has yet to be identified [18]. Whether or not nateglinide is a substrate for an efflux transporter, such as P-glycoprotein [19], is not known. From the systemic circulation, nateglinide is eliminated primarily via oxidative biotransformation [2]. CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 have been suggested to take part in the metabolism of nateglinide, with CYP2C9 metabolizing it to a much greater extent than CYP3A4 [2, 3]. The biotransformation of nateglinide yields several metabolites, of which the dehydrogenated M7 metabolite seems to be as potent a blood glucose-lowering agent as the parent nateglinide [20]. However all other metabolites appear to be much less active [20]. Total exposure to M7 is about 5% of that of nateglinide [2]. Because of its low lipophilicity, nateglinide may require active uptake from blood into the liver to become available for hepatic drug metabolism.

Rifampicin is a well-established potent inducer of several drug-metabolizing enzymes and has also been shown to induce the expression of some efflux transporters in humans [8, 12, 13]. It is possible that rifampicin induces also some uptake transporters, such as an organic anion-transporting polypeptide (OATP) [17, 21]. In the present study, we could not find evidence to support induction of the oxidative biotransformation of nateglinide by rifampicin, because the M7/nateglinide AUC ratios were not significantly changed. However, M7 is further oxidized to metabolites M11 and M12 [2] and it is possible that rifampicin induced the further metabolism of M7, as suggested by the reduction in its t1/2. Furthermore, M7 represents only part of the total metabolism of nateglinide [2] and rifampicin may have induced the metabolism of nateglinide via another pathway [5]. Nevertheless, considering that nateglinide is eliminated largely by oxidative biotransformation [2] and that rifampicin has its greatest inducing effects on CYP enzymes [8], the most likely explanation for this rifampicin–nateglinide interaction is induction of the CYP-mediated biotransformation of nateglinide by rifampicin.

In one subject (2), the absorption of nateglinide appeared to be considerably decreased during the rifampicin phase, resulting in flip-flop kinetics and a markedly diminished systemic exposure to the drug. This was associated with a considerable increase in the blood glucose concentration in this subject. However, during the placebo phase, nateglinide seemed to be absorbed more rapidly resulting in higher Cmax in this subject than in the other subjects.

In a previous study, an identical pretreatment with rifampicin decreased the AUC(0,∞) of the meglitinide analogue repaglinide, a substrate of CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 [22], by 57% and also significantly decreased its blood glucose-lowering effect [14]. In addition, the same rifampicin pretreatment has been shown to decrease the AUC(0,∞) of the sulphonylureas and CYP2C9 substrates [23–25] glibenclamide, glimepiride and glipizide by 39%, 34% and 22%, respectively [16, 17]. In these studies, rifampicin also significantly decreased the blood glucose-lowering effect of glibenclamide, a finding in agreement with data from patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus [15]. Of these antidiabetic drugs, nateglinide and glipizide seem to be least susceptible to an interaction with rifampicin. However, because of interindividual variation in the extent of this interaction, the effects of nateglinide may be decreased by rifampicin in some patients with diabetes. Therefore it is advisable to monitor blood glucose concentrations if rifampicin is added to the treatment of a patient taking nateglinide and when rifampicin treatment is discontinued. Nateglinide dosage should be adjusted as necessary.

In conclusion, rifampicin modestly decreased the plasma concentrations of nateglinide probably by inducing its oxidative biotransformation via CYP2C9. In some patients, rifampicin may decrease the blood glucose-lowering effect of nateglinide.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr Jouko Laitila, Mrs Kerttu Mårtensson, Mrs Eija Mäkinen-Pulli and Mrs Lisbet Partanen for skilful technical assistance. This study was supported by grants from the Helsinki University Central Hospital Research Fund and the National Technology Agency (Tekes).

References

- 1.Dornhorst A. Insulinotropic meglitinide analogues. Lancet. 2001;358:1709–1716. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06715-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weaver ML, Orwig BA, Rodriguez LC, et al. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of nateglinide in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:415–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn CJ, Faulds D. Nateglinide. Drugs. 2000;60:607–615. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Back DJ, Tjia JF, Karbwang J, Colbert J. In vitro inhibition studies of tolbutamide hydroxylase activity of human liver microsomes by azoles, sulphonamides and quinolines. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;26:23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1988.tb03359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wienkers LC, Wurden CJ, Storch E, Kunze KL, Rettie AE, Trager WF. Formation of (R) -8-hydroxywarfarin in human liver microsomes. A new metabolic marker for the (S) -mephenytoin hydroxylase, P4502C19. Drug Metab Dispos. 1996;24:610–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Back DJ, Tjia JF. Comparative effects of the antimycotic drugs ketoconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole and terbinafine on the metabolism of cyclosporin by human liver microsomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;32:624–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb03963.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niemi M, Neuvonen M, Juntti-Patinen L, Backman JT, Neuvonen PJ. Effect of fluconazole on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nateglinide. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:25–31. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niemi M, Backman JT, Fromm MF, Neuvonen PJ, Kivistö KT. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003. Pharmacokinetic interactions with rifampicin: clinical relevance. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Syvälahti E, Pihlajamäki K, Iisalo E. Effect of tuberculostatic agents on the response of serum growth hormone and immunoreactive insulin to intravenous tolbutamide, and on the half-life of tolbutamide. Int J Clin Pharmacol Biopharm. 1976;13:83–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heimark LD, Gibaldi M, Trager WF, O'Reilly RA, Goulart DA. The mechanism of the warfarin–rifampin drug interaction in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1987;42:388–394. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1987.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Backman JT, Olkkola KT, Neuvonen PJ. Rifampin drastically reduces plasma concentrations and effects of oral midazolam. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;59:7–13. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greiner B, Eichelbaum M, Fritz P, et al. The role of intestinal P–glycoprotein in the interaction of digoxin and rifampin. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:147–153. doi: 10.1172/JCI6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fromm MF, Kauffmann HM, Fritz P, et al. The effect of rifampin treatment on intestinal expression of human MRP transporters. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1575–1580. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64794-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niemi M, Backman JT, Neuvonen M, Neuvonen PJ, Kivistö KT. Rifampin decreases the plasma concentrations and effects of repaglinide. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;68:495–500. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2000.111183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surekha V, Peter JV, Jeyaseelan L, Cherian AM. Drug interaction: rifampicin and glibenclamide. Natl Med J India. 1997;10:11–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niemi M, Kivistö KT, Backman JT, Neuvonen PJ. Effect of rifampicin on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of glimepiride. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;50:591–595. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Niemi M, Backman JT, Neuvonen M, Neuvonen PJ, Kivistö KT. Effects of rifampin on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of glyburide and glipizide. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:400–406. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.115822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okamura A, Emoto A, Koyabu N, Ohtani H, Sawada Y. Transport and uptake of nateglinide in Caco-2 cells and its inhibitory effect on human monocarboxylate transporter MCT1. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;137:391–399. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fromm MF. P-glycoprotein. a defense mechanism limiting oral bioavailability and CNS accumulation of drugs. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;38:69–74. doi: 10.5414/cpp38069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takesada H, Matsuda K, Ohtake R, et al. Structure determination of metabolites isolated from urine and bile after administration of AY4166, a novel d-phenylalanine-derivative hypoglycemic agent. Bioorg Med Chem. 1996;4:1771–1781. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(96)00187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staudinger J, Liu Y, Madan A, Habeebu S, Klaassen CD. Coordinate regulation of xenobiotic and bile acid homeostasis by pregnane X receptor. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:1467–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bidstrup TB, Bjørnsdottir I, Thomsen MS, Hansen KT. CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 are the principle enzymes involved in the in vitro biotransformation of the insulin secretagogue repaglinide. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;89(Suppl 1):64. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kidd RS, Straughn AB, Meyer MC, Blaisdell J, Goldstein JA, Dalton JT. Pharmacokinetics of chlorpheniramine, phenytoin, glipizide and nifedipine in an individual homozygous for the CYP2C9*3 allele. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:71–80. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199902000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirchheiner J, Brockmöller J, Meineke I, et al. Impact of CYP2C9 amino acid polymorphisms on glyburide kinetics and on the insulin and glucose response in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;71:286–296. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.122476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niemi M, Cascorbi I, Timm R, Kroemer HK, Neuvonen PJ, Kivistö KT. Glyburide and glimepiride pharmacokinetics in subjects with different CYP2C9 genotypes. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72:326–332. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.127495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]