Abstract

Aims

To investigate uptake of fluconazole into the interstitial fluid of human subcutaneous tissue using the microdialysis and suction blister techniques.

Methods

A sterile microdialysis probe (CMA/60) was inserted subcutaneously into the upper arm of five healthy volunteers following an overnight fast. Blisters were induced on the lower arm using gentle suction prior to ingestion of a single oral dose of fluconazole (200 mg). Microdialysate, blister fluid and blood were sampled over 8 h. Fluconazole concentrations were determined in each sample using a validated HPLC assay. In vivo recovery of fluconazole from the microdialysis probe was determined in each subject by perfusing the probe with fluconazole solution at the end of the 8 h sampling period. Individual in vivo recovery was used to calculate fluconazole concentrations in subcutaneous interstitial fluid. A physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model was used to predict fluconazole concentrations in human subcutaneous interstitial fluid.

Results

There was a lag-time (approximately 0.5 h) between detection of fluconazole in microdialysate compared with plasma in each subject. The in vivo recovery of fluconazole from the microdialysis probe ranged from 57.0 to 67.2%. The subcutaneous interstitial fluid concentrations obtained by microdialysis were very similar to the unbound concentrations of fluconazole in plasma with maximum concentration of 4.29 ± 1.19 µg ml−1 in subcutaneous interstitial fluid and 3.58 ± 0.14 µg ml−1 in plasma. Subcutaneous interstitial fluid-to-plasma partition coefficient (Kp) of fluconazole was 1.16 ± 0.22 (95% CI 0.96, 1.35). By contrast, fluconazole concentrations in blister fluid were significantly lower (P < 0.05, paired t-test) than unbound plasma concentrations over the first 3 h and maximum concentrations in blister fluid had not been achieved at the end of the sampling period. There was good agreement between fluconazole concentrations derived from microdialysis sampling and those estimated using a blood flow-limited PBPK model.

Conclusions

Microdialysis and suction blister techniques did not yield comparable results. It appears that microdialysis is a more appropriate technique for studying the rate of uptake of fluconazole into subcutaneous tissue. PBPK model simulation suggested that the distribution of fluconazole into subcutaneous interstitial fluid is dependent on tissue blood flow.

Keywords: fluconazole, human, microdialysis, pharmacokinetics, suction blisters, tissue distribution

Introduction

The incidence of fungal infections has significantly increased in the last three decades [1]. Life threatening fungal infections are becoming a serious problem due to the marked increase in the population of immunocompromised or severely ill individuals as a result of the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections, the increased use of immunosuppresive agents in association with organ transplantation, chemotherapy and improved life-saving medical procedures requiring indwelling catheters [2]. Candidaemia and disseminated fungal infections are invasive in nature and may lead to significant mortality in critically ill patients. Fluconazole, a bis tri-azole antifungal agent, is used in the prevention and treatment of systemic and superficial fungal infections which predominantly affect immunocompromised individuals [3].

Successful treatment with an antifungal agent relies on achieving adequate concentrations at the site of fungal infection. In most cases, the site of infection is outside the vascular system and therefore information on antifungal tissue concentrations is more important than the plasma concentrations in understanding the efficacy of antifungal agents. However, obtaining samples of human tissues is problematic due to the invasive nature of tissue sampling procedures. Tissue biopsy is the most common method used in the study of drug tissue distribution in humans but this approach has limitations with respect to the number of samples that can be collected per subject and therefore the sparse nature of the data obtained [4, 5]. Furthermore, because homogenization disrupts all tissue components, the drug concentration obtained using this technique represents an average tissue concentration across the whole tissue, including residual blood entrapped in the tissue, intracellular fluid, interstitial fluid and structural tissue components.

Distribution of fluconazole has been studied in various human tissues, including brain [6, 7], gynaecological tissues (uterus, ovaries and oviducts) [8], pancreas [9], prostate [10], hair scalp [11], skin [12, 13], nails [14] and body fluids, including saliva [15], sputum [16], cerebrospinal fluid [17], joint fluid [18], vaginal secretions [19], aqueous humour [20], urine and dialysate from continuous ambulatory patients [21], as well as in blister fluid [22]. All these studies rely on discrete and limited sampling points. The pharmacological action of a drug will generally be dependent on the dynamic processes of drug movement into, and out of, the tissue. Continuous sampling of drug tissue concentrations can provide a more thorough description of the rate and extent of tissue uptake and hence lead to more rational design of drug dosing schedules.

In contrast to the average concentration obtained using tissue biopsy and sample homogenization, microdialysis continuously samples the unbound concentrations of drugs in the interstitial fluid. While microdialysis has been used to study the distribution of fluconazole into brain tissue of rats [23], there have been no reports of the microdialysis technique being utilized to study tissue distribution of fluconazole in humans. Blister fluid sampling is a well-established method used for examining tissue distribution of anti-infective drugs. However, many variables potentially affect the results obtained from blister fluid sampling, including the size of the blisters [24], the degree of inflammation due to blister induction or underlying pathology [25], the timing of blister formation [26] and the possibility of protein accumulation in the blister fluid over time [27]. These variables may complicate interpretation of tissue concentration data obtained using this technique.

In the present study, the distribution of fluconazole into human subcutaneous interstitial fluid was investigated using microdialysis following administration of a single 200 mg oral dose. The results were compared with data obtained simultaneously using the suction blister fluid technique. A hybrid physiologically based pharmacokinetic model was then used to characterize the distribution of fluconazole into subcutaneous interstitial fluid.

Methods

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of St Vincent's Hospital and Human Ethics Committee of The University of Sydney and performed in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki and the Code of Practice of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. The clinical study was conducted at the St Vincent's Clinical Trials Centre, St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney.

Subjects

Five healthy, drug free, male volunteers aged between 25 and 52 years and weighing between 65 and 72 kg were enrolled in this study. Health status was assessed on the basis of medical history, physical examination including a blood pressure check and an ECG, and blood examination. Volunteers with a history of impaired renal and/or hepatic function were excluded. All volunteers were given a detailed description of the study and their written consent was obtained.

Microdialysis system

Sterile human microdialysis probes (CMA/60, CMA Microdialysis, Stockholm, Sweden) with a 20 mm shaft length, 0.6 mm diameter and 30 mm dialysis membrane length with a molecular weight cut-off of 20 kDa, were employed in this study. Once inserted, the probe was perfused with sterile saline at a flow rate of 1 µl min−1 using a CMA/101 microdialyser (CMA Microdialysis, Stockholm, Sweden). Microdialysate samples (20 µl) were collected every 20 min during the study.

Study protocol

The first phase of the study was induction of blisters. The blister capsule, consisting of a stainless steel base containing nine holes (8 mm diameter), was attached to the skin of the inner side of the left forearm and connected to a pump to produce controlled gentle suction (−40 kPa). The fluid filled blisters (approximate area 0.5 cm2 if the blister was completely formed; 100–150 µl fluid per blister) were generated over 1.5–2 h.

Once the blister induction was commenced, the microdialysis probe was inserted subcutaneously into the upper left arm after injection of local anaesthetic (lignocaine 2%, Xylocaine, Astra Zeneca, Australia, injection volume < 1.5 ml) into the site of probe insertion. This schedule allowed the tissue some time to recover from any trauma caused by inserting the probe while the blisters were forming.

The microdialysis probe was inserted as follows: the skin was firstly punctured with a needle and the slit cannula introducer with the attached microdialysis probe was inserted into the subcutaneous tissue. The introducer was withdrawn leaving the probe implanted in the subcutaneous tissue. The probe was secured to the skin using sterile tape (Steri-Strip®, 3M, USA) and the site was covered with a transparent semipermeable dressing (OpSite®, Smith & Nephew, England). The probe inlet tube was connected to a microsyringe filled with sterile saline. During the probe insertion procedure subjects remained in the supine position. At least 1 h equilibration time was allowed prior to drug administration during which time dialysate was collected and analysed to evaluate whether there was any analytical interference from other substances in the dialysate (e.g. the local anaesthetic).

An intravenous cannula (17 G, Venflon®, Ohmeda AB, Sweden) was inserted into a left forearm vein for blood sampling. During the sampling period the subjects remained seated. The study room temperature was maintained at 20–22 °C. During the 8 h sampling period, the probe was disconnected from the pump to allow the subjects to be mobile for a short period (no longer than 10 min), if needed. Prior to re-starting the dialysate sample collection, the line was flushed to remove the drug from the outlet tubing. Then, the perfusate flow rate was adjusted to 1 µl min−1 and time was allowed to compensate for the dead volume of the microdialysis probe (3 µl). The dialysate time sampling point was accordingly adjusted to the time when the dialysate sample collection was re-started. Subjects were questioned regularly about any pain, discomfort or associated sensations at the various sampling sites. Subjects were followed up with respect to any side-effects or discomfort due to the procedures performed in the study for some days after the study.

Drug administration

Fluconazole was given as a single oral dose (200 mg capsule, Diflucan®, Pfizer, Australia) taken with 200 ml water following an overnight fast. Food was not allowed until 4 h postdose but water was allowed 2 h postdose.

Sampling procedure

Dialysate samples (20 µl) were continuously collected throughout the 8 h sampling period. An external standard (10 µl laudanosine, Sigma, Australia, 1.5 µg ml−1 in methanol) was immediately added to each sample to correct for possible variability in the HPLC injection volume. Dialysate sample was collected directly following drug administration and the time point for the first microdialysate sample was accordingly adjusted for the dead volume of the probe to the sample vial (3 µl). Dialysate samples were kept refrigerated until the time of analysis.

Blood samples (∼ 8 ml) were withdrawn prior to dosing and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 8 h postdose into heparinized tubes and, once harvested, the plasma samples were kept frozen until the time of analysis. An individual blister was aspirated prior to dosing and at 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 5 and 8 h postdose using a 0.5-ml syringe (29 gauge needle). The skin was cleaned using an alcohol swab before and after blister fluid sampling. In some cases, all nine blisters were not completely formed. If there was an inadequate number to allow sampling at each proposed time point, the 0.5 h sample was omitted.

Determination of microdialysis in vivo recovery

At the end of the 8 h sampling period the in vivo recovery of the microdialysis probe was determined in each subject by perfusing the probe with fluconazole solution (12 µg ml−1). The flow rate and the dialysate volume collected were the same as used in the main part of the study and three samples were collected. In one subject, the in vivo recovery was also determined by perfusing the probe with a lower concentration of fluconazole solution (3 µg ml−1) for 2.5 h without administering the drug. Dialysate samples were assayed for fluconazole concentration and the relative loss of fluconazole into the tissue was used as an estimate of the in vivo recovery.

Plasma protein binding

Fluconazole plasma protein binding was determined for each subject by ultrafiltration using Amicon Centrifree® Micropartition Device (Millipore, NSW, Australia). Plasma (400 µl) from the 4 h sampling point was pipetted into the ultrafiltration device and centrifuged using a fixed angle rotor centrifuge ( Jouan, CT 422) at 37 °C at 1800 g for 20 min The ultrafiltrate was collected and analysed for fluconazole. The unbound fraction was calculated by dividing the fluconazole concentration in the ultrafiltrate by the corresponding plasma concentration determined prior to ultrafiltration.

The plasma protein binding was additionally determined from samples collected at 1 h and 4 h from a single subject, and binding was also investigated in diluted plasma (50% plasma diluted with normal saline) to simulate the expected protein concentrations in the blister fluid. (It has been shown that blister fluid has similar protein composition to plasma, except that the concentration of each protein is approximately 30% to 50% of that reported in plasma) [26, 28]. The determination of protein binding was performed in triplicate.

Sample analyses

The HPLC assay for fluconazole was modified from the published assays by Flores-Murrieta [29] and Yang et al.[23] and validated to measure fluconazole concentrations in different matrixes including human plasma, blister fluid and microdialysate.

Fluconazole in plasma, blister fluid and microdialysate samples was quantified using a reversed phase HPLC system comprising a Shimadzu LC-10AS solvent delivery pump, a GBC autoinjector (LC1610), a Shimadzu SPD-10Avp variable wavelength UV-VIS detector (set at 210 nm) connected to a personal computer with PE Nelson Turbochrom Professional (version 4.1) peak integration software. An Alltima® C18 analytical column (150 × 2.1 mm ID, 5 µm particle size) preceded by an Alltima® C18 guard column (7.5 × 4.6 mm ID, 5 µm particle size) from Alltech Associates (NSW, Australia) was used. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and water containing 0.05 m di-sodium hydrogen orthophosphate adjusted to pH 4 with orthophosphoric acid in a ratio of 20 : 80 (v : v) for plasma and blister fluid, and 17 : 83 (v : v) for microdialysate samples. The mobile phase was degassed under vacuum and filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane filter (Millipore®, Sydney Australia) prior to use. The flow rate was 0.3 ml min−1.

To plasma or blister fluid samples (50 µl) was added UK-54373 (5 µl, 30 µg ml−1; Pfizer Central Research, Sandwich, United Kingdom) as an internal standard and carbonate buffer (pH 9, 50 µl). The samples were extracted with dichloromethane (2 ml) using a roller mixer (Ratek Instrument, Australia) for 15 min. The mixture was centrifuged (2500 rev min−1, 15 min; Universal 16 A, Hettich Zentrifugen, Tuttlingen, Germany). The organic phase was separated and transferred to a borosilicate test tube and then evaporated under a gentle stream of nitrogen. The resulting residue was reconstituted in mobile phase (50 µl) and an aliquot (10 µl) was injected into the HPLC system. Retention times for fluconazole and UK-54373 were 6.6 and 12.9 min, respectively, from both plasma and blister fluid samples. Microdialysate samples (10 µl) were assayed directly without any sample preparation. Retention times of fluconazole and laudanosine (external standard) were 7.9 and 21.9 min, respectively, from microdialysate samples.

Quantification of fluconazole was performed using calibration curves which were prepared in duplicate for each matrix and run at the beginning and the end of the analysis. Calibration standards for blister fluid were prepared using blank plasma diluted 50% with normal saline to simulate the blister fluid matrix. The limit of quantification of fluconazole was 0.2 µg ml−1 in all matrices with intra- and interday accuracy and imprecision (CV) of < 13% over the concentration range of 0.2–30 µg ml−1 (plasma and blister fluid) using 50 µl plasma samples or 50 µl diluted plasma (50% with normal saline) and 0.2–30 µg ml−1 (dialysate) using 20 µl dialysate samples.

Data analysis

Unbound plasma concentrations of fluconazole for each subject were estimated using the ex vivo protein binding determined for that subject. In vivo microdialysis recovery was determined as the relative loss of fluconazole from the probe into the tissue. The in vivo recovery for each individual probe in each subject was used to calculate the ‘true’ subcutaneous interstitial fluid concentrations of fluconazole from the observed dialysate concentrations by dividing the observed dialysate concentrations by the in vivo recovery.

The extent of fluconazole distribution into subcutaneous tissue was quantified using the subcutaneous interstitial fluid-to-plasma partition coefficient (Kp), which was estimated by comparing fluconazole area under the concentration time curve in subcutaneous interstitial fluid (AUC(0,8 h)SCIF) obtained from microdialysis sampling with unbound plasma (AUC(0,8 h)) from blood sampling [30]. The AUC was determined using the linear trapezoidal rule. Maximum concentration and time to maximum concentration of fluconazole in plasma, microdialysate and blister fluid sampling were determined from the observed data.

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PB-PK) model simulation

The nature of fluconazole uptake into subcutaneous tissue was investigated using a blood-flow limited hybrid PB-PK model (Equation 1) to simulate fluconazole concentrations in subcutaneous interstitial fluid.

|

where VSCIF is the volume of human subcutaneous interstitial fluid, Cp represents fluconazole plasma concentrations, QSC is the blood flow to human subcutaneous tissue, Kp is subcutaneous interstitial fluid-plasma partition coefficient and CSCIF represents fluconazole subcutaneous interstitial fluid concentrations. In this simulation, estimates of VSCIF and QSC were obtained from the literature. VSCIF is approximately 1.4% of body weight and QSC is 0.19 ml min−1 for a 70 kg male [31]. Kp was obtained from the experimental study and calculated as described above. Cp, which served as a forcing function in the hybrid PB-PK model, was obtained from the plasma concentration-time data of fluconazole obtained from this study with 8 h sampling and was fitted using a bi-exponential equation (SCIENTIST® software). In a second simulation Cp was also derived using population pharmacokinetic parameters of fluconazole obtained from the literature [32, 33]. A one compartment pharmacokinetic model with first order input was employed (Equation 2) [32].

|

where F [0.98] is the fraction of the dose reported to be absorbed orally [32], dose is 200 mg, ka is a first-order absorption rate constant (0.93 h−1), V is volume of distribution (57.4 l) and CL is clearance (0.79 l h−1) [33]. PB-PK model simulations were generated using the SCIENTIST® software and the results (after incorporating the 0.5 h lag-time of penetration of fluconazole into subcutaneous interstitial fluid observed in this study) were compared with the observed data for fluconazole concentrations in subcutaneous interstitial fluid obtained by microdialysis sampling.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SD, unless otherwise specified. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (for Windows release 8).

Results

Individual in vivo recovery of fluconazole by the microdialysis probe was highly reproducible (Table 1). Similar results for in vivo recovery were obtained using fluconazole solution of either 3 or 12 µg ml−1 in the perfusate.

Table 1.

In vivo recovery of fluconazole from the microdialysis probe in individual subjects determined at the end of the sampling period by perfusing the probe with fluconazole solution (12 µg ml−1), n = 3. (Note: in subject 1*, the in vivo recovery was determined on a separate occasion without administering fluconazole and a fluconazole solution of 3 µg ml−1 was used as the perfusate, n = 7).

| Subject | In vivo recovery (%) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 58.5 ± 1.9 |

| 2 | 57.6 ± 0.3 |

| 3 | 67.2 ± 3.0 |

| 4 | 57.7 ± 3.6 |

| 5 | 57.0 ± 4.2 |

| 1* | 57.0 ± 4.2 |

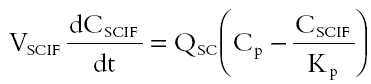

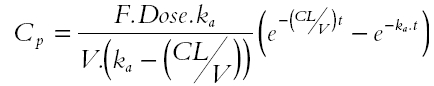

The unbound concentration-time profiles of fluconazole in individual subjects (Figure 1) and the average results for five subjects (Figure 2), following a single 200 mg oral administration of fluconazole demonstrated greater similarities between plasma and microdialysate than between the plasma and the blister profiles. The time points for the microdialysate concentrations are presented at the mid-points of the sampling interval since microdialysis sampling is a continuous process over discrete time intervals. Microdialysis samples the unbound drug concentrations and for comparison plasma concentrations are also presented as the unbound concentrations.

Figure 1.

Concentration-time profiles of fluconazole in plasma (unbound), microdialysate and blister fluid in individual subjects following single 200 mg oral administration of fluconazole.

Figure 2.

Concentration time profiles of fluconazole obtained from three different sampling approaches, i.e. blood, microdialysis and blister fluid sampling, following single 200 mg oral administration. Data presented as mean + SD from five subjects. Unbound plasma (▪); microdialysis (▴); and blister fluid (•).

The ex vivo plasma protein binding data for fluconazole were moderately variable ranging from 10 to 29% (18 ± 7%, mean ± SD, n = 5). This finding is in agreement with other published mean data which reported that the protein binding of fluconazole in human plasma was ∼ 12% [34]. Determination of ex vivo plasma protein binding using samples obtained at different time points, i.e. 1 and 4 h which corresponded to plasma concentrations of 1.6 and 3.2 µg ml−1, respectively, showed similar protein binding results (16%) suggesting that there was no concentration or time dependence in plasma protein binding of fluconazole. Fluconazole in the simulated blister fluid matrix (50% diluted plasma) showed negligible binding to plasma proteins (< 3%). Consequently concentrations of fluconazole in blister fluid were not corrected for the effect of protein binding.

Maximum unbound concentrations (Cmax) of fluconazole were 3.58 ± 0.14 µg ml−1 and 4.29 ± 1.19 µg ml−1, respectively, in plasma and subcutaneous interstitial fluid obtained from microdialysis sampling (n = 5), whereas maximum concentration of fluconazole in blister fluid had not been achieved at the end of 8 h sampling period in most cases. Times to the maximum concentration (tmax) were 3.17 ± 0.84 h and 3.56 ± 0.87 h in plasma and subcutaneous interstitial fluid, respectively (n = 5). There were no differences in either Cmax or tmax of fluconazole in unbound plasma compared to these values for subcutaneous interstitial fluid (P > 0.05, paired t-test). Subcutaneous interstitial fluid-to-plasma partition coefficient (Kp) of fluconazole was determined to be 1.16 ± 0.22 (95% CI; 0.96, 1.35; n = 5) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Subcutaneous interstitial fluid-to-plasma partition coefficient (Kp) of fluconazole determined as the ratio of the area under the curve of subcutaneous interstitial fluid concentration to the area under the curve of unbound plasma concentration obtained from 8 h sampling (AUCSCIF (0,8 h) : AUCunbound plasma (0,8 h).

| Subject | AUCunbound plasma(0,8 h) (µg l−1h) | AUCSCIF(0,8 h) (µg l−1h) | Kp |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18.74 | 19.04 | 1.02 |

| 2 | 17.68 | 26.04 | 1.47 |

| 3 | 14.26 | 16.02 | 1.12 |

| 4 | 24.89 | 31.80 | 1.28 |

| 5 | 27.92 | 25.24 | 0.90 |

| Mean | 20.70 | 23.63 | 1.16 |

| SD | 5.57 | 6.21 | 0.22 |

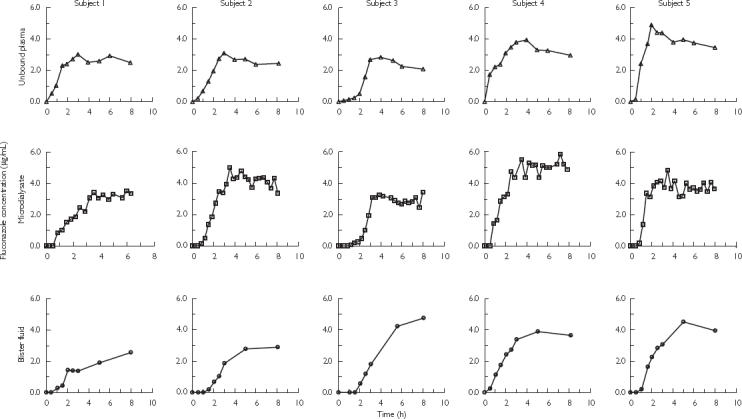

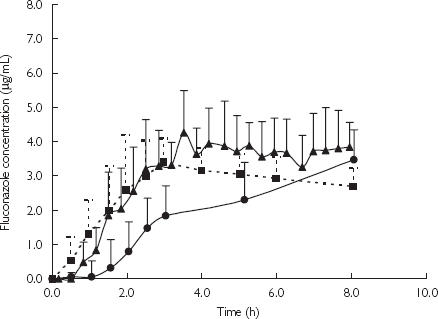

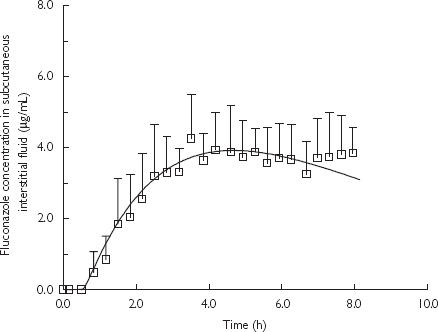

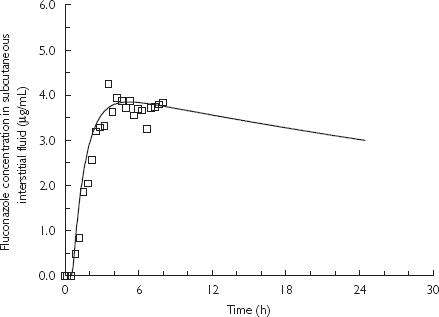

Good agreement was obtained between the results of PB-PK simulation and the subcutaneous interstitial fluid concentrations obtained using microdialysis sampling (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Predicted fluconazole concentration-time profiles in subcutaneous interstitial fluid using PB-PK model simulation and observed concentrations (mean + SD, n = 5) measured by microdialysis following oral dose (200 mg) administration of fluconazole in humans. A bi-exponential equation was used as a forcing function of experimental plasma concentrations of fluconazole obtained over 8 h sampling. PB-PK simulation (—); and microdialysis sampling data (□).

Figure 4.

Predicted fluconazole concentration-time profiles in subcutaneous interstitial fluid using PB-PK model simulation based on population pharmacokinetic parameters for fluconazole and observed concentrations (mean, n = 5) measured by microdialysis following an oral 200 mg dose of fluconazole in humans. A one compartment pharmacokinetic model with first-order input was used as a forcing function of plasma concentrations. PB-PK simulation (—); and microdialysis sampling data (□).

Discussion

In this study, the distribution of fluconazole was investigated in humans using the microdialysis technique to continuously sample the unbound concentration of fluconazole in the interstitial fluid of subcutaneous tissue. Determination of fluconazole concentrations in suction blister fluid, which is a well-established method for investigating the distribution of drugs into tissue, was also performed. A single dose rather than multiple doses of fluconazole as generally used in previous tissue distribution studies was selected in order to investigate unambiguously the rate of drug appearance in plasma and uptake into the tissue.

Assessment of in vivo recovery is an essential part of using microdialysis to study drug pharmacokinetics. In this study, in vivo recovery was determined at the end of the sampling period. The perfusate concentration of the drug used for calibration was significantly higher than the expected tissue concentration which ensured diffusion occurred from the probe to the tissue. In one subject the in vivo recovery was investigated by perfusing the probe with fluconazole solution (3 µg ml−1) for 2.5 h without administration of fluconazole and the estimated in vivo recovery of fluconazole was 57.0 ± 4.2% (n = 7). A significantly higher concentration of fluconazole (12 µg ml−1) was used in the perfusate to determine the in vivo recovery in each subject at the end of the sampling period. In vivo recovery of fluconazole assessed using different perfusate concentrations confirmed that there was no concentration dependency in the in vivo recovery (Table 1).

Insertion of the microdialysis probe has been reported to be well tolerated [35, 36]. However, it remains an invasive procedure and in the present study a local anaesthetic (lignocaine) was injected around the insertion site to minimize discomfort. The microdialysis probe membrane is nonspecific in that any compound in the interstitial fluid that is below the molecular size cut-off of the dialysis membrane has the potential to diffuse into the perfusate. HPLC analysis of the microdialysate samples collected immediately after probe insertion exhibited a large peak that eluted immediately before fluconazole and affected the chromatographic baseline around the elution time of the fluconazole peak, potentially compromising the accurate assessment of the peak area of this analyte. The interfering peak was confirmed to have the same retention time as lignocaine. Consequently, the amount of local anaesthetic used was controlled (lignocaine 2% with injection volume < 1.5 ml) in order to achieve an adequate anaesthetic effect without interference to the fluconazole HPLC assay. Chromatograms of microdialysate samples collected at different times during the study demonstrated that there was no interference to the analysis of fluconazole or the internal standard by endogenous compounds.

The time course of fluconazole concentrations in subcutaneous interstitial fluid mirrored the unbound plasma concentrations for each subject except for a delay or lag-time of approximately 0.5 h (Figure 2). From approximately 1.5 h onwards, unbound concentrations in plasma and subcutaneous interstitial fluid were in general agreement. The extent of tissue uptake of fluconazole was characterized by the subcutaneous interstitial fluid-to-plasma partition coefficient (Kp) of fluconazole (Table 2). The sampling period employed in this study was 8 h which was notably shorter than the reported half-life of fluconazole in humans (∼ 32 h) [34]. Applying the estimated AUC0-∞ to the calculation of Kp could not be justified because of the limited sampling period. Therefore, truncated area under the concentration-time curve (AUC(0,8 h)), instead of AUC(0,∞), was used in the calculation of Kp. Concentrations in subcutaneous interstitial fluid showed rapid equilibrium with the plasma concentrations even during the distribution phase. Pseudoequilibrium between plasma and subcutaneous interstitial fluid concentrations was achieved within the 8 h sampling period which supported the rationale for using the truncated AUC(0,8 h) for determination of Kp. The Kp for the uptake of fluconazole into blister fluid was not quantified since equilibrium between plasma and blister fluid was not achieved within the 8-h sampling period and thus these data could not be used to accurately determine the tissue uptake of fluconazole. In subject 3 (Figure 2) there was a significant delay in the appearance of fluconazole in the subcutaneous interstitial fluid. However, a similar delay was also observed with respect to plasma concentrations suggesting that this was likely to be due to slower absorption in this subject rather than attributable to slow tissue uptake of fluconazole. In three of the five subjects the subcutaneous interstitial fluid concentrations exceeded the unbound plasma concentrations. This was unexpected and the reason for this is unclear but is unlikely to be due to analytical error (given the reliable HPLC assay performance) or problems in estimating in vivo recovery (which was done for each individual subject).

In contrast to the microdialysis data, concentrations achieved in the blister fluid were significantly delayed and were lower compared with unbound plasma concentrations or subcutaneous interstitial fluid concentrations over the first 3 h (except for subject 3). Furthermore, in the majority of subjects maximum concentrations in the blister fluid had not been achieved by the end of the 8-h sampling period. A delay in the distribution of drugs into blister fluid compared with plasma has been reported in a number of studies [37–42]. Some authors have suggested that blisters may not accurately represent a peripheral compartment [39], particularly for highly bound drugs due to the issues of low surface area/volume (SA/V), protein accumulation in blister fluid over time, and the degree of inflammation at the blister site. It has been suggested that, blister fluid sampling is most appropriate for monitoring tissue uptake of drugs with low protein binding [43].

The lag time in penetration of fluconazole into blister fluid was an interesting observation given the low protein binding of fluconazole. If the drug is already in the tissue as demonstrated by microdialysis sampling, but not in the blister fluid, the question arises as to whether concentration-time profiles of a drug in the blister fluid can be used to determine the rate of tissue uptake of a drug. To establish the utility of blister fluid and microdialysis sampling, studies should be performed during both the uptake and efflux of drug from tissue after single and multiple doses. However, one impediment to this is that suction blisters tend to collapse 12–24 h after induction due to reabsorption of the blister fluid [26]. While this might be overcome by generating blisters at different times over the time course of the study, there is evidence that there are differences in penetration of a drug into blister fluid depending on the time of blister induction relative to the time of drug administration (prior to or after drug administration) [26, 42]. For these reasons it is difficult to perform a thorough comparison between microdialysis and blister fluid sampling techniques.

The concentration of drug in the peripheral tissue close to the site of action provides insight into drug pharmacodynamics [44]. Therefore, the delay in drug penetration into blister fluid and the extended redistribution from the blister fluid make the blister fluid technique of doubtful value to the study of the rate of tissue penetration of a drug as demonstrated by fluconazole. However, blister fluid sampling might remain a valuable tool for the investigation of the extent of tissue uptake of a drug at steady-state.

In order to characterize the uptake of fluconazole into subcutaneous interstitial fluid, simulations were performed to predict the concentrations of fluconazole in the fluid using a blood-flow limited hybrid PB-PK model. The unbound plasma concentrations of fluconazole over the 8 h sampling obtained from this study were used as a forcing function in this simulation (Figure 3). Notwithstanding the limited sampling period performed in this study, i.e. 8 h, which is shorter than the reported half-life of fluconazole in humans (∼ 32 h) [34], the aim of this study was to investigate the tissue uptake of fluconazole into subcutaneous interstitial fluid using microdialysis and not to systematically characterize the pharmacokinetic behaviour in plasma. However, accurate estimation of pharmacokinetic parameters of fluconazole was unlikely to be obtained from the limited sampling period performed in this study. Therefore, the PB-PK simulation was extended over a typical dosing interval by employing population pharmacokinetic parameters of fluconazole obtained from the literature [32, 33] to derive plasma concentrations which served as a forcing function in the PB-PK simulation. An excellent agreement was again shown between the PB-PK simulation and the concentration data of fluconazole in subcutaneous interstitial fluid obtained using microdialysis (Figure 4). Results from both PB-PK simulations clearly indicated that the uptake of fluconazole into subcutaneous interstitial fluid is dependent on the blood flow into subcutaneous tissue. In this study subjects received a single 200 mg dose of fluconazole and rapidly achieved concentrations in subcutaneous interstitial fluid capable of inhibiting the growth of the majority of candida species [45]. Simulations presented in Figure 4 indicate that effective concentrations were sustained over the 24 h doing interval.

The microdialysis and blister fluid techniques were both well tolerated by the subjects. Although the insertion of the microdialysis probe was performed under local anaesthesia, some subjects indicated some reservations about this procedure due to the size of the guide needle used for inserting the probe. However, during and at the end of the study all subjects found the microdialysis technique acceptable. There was no sign of bruising or pain once the probe was removed from the tissue. Blister induction was not a painful process but slight discomfort was felt when the blister formation was at the time of obvious dermal-epidermal separation. Blisters took a longer time to resolve than the microdialysis probe insertion site and in some subjects fluid-filled blisters reformed several days after the study. The scarring and/or depigmentation that resulted from the blister induction remained for more than 1 month.

Conclusions

Microdialysis sampling provided subcutaneous interstitial fluid concentrations of fluconazole which paralleled the unbound plasma concentrations with an initial approximately 0.5 h delay in the uptake into tissue following a single oral dose of drug. There were no significant differences in the Cmax and tmax of fluconazole with respect to unbound plasma and subcutaneous interstitial fluid obtained from microdialysis sampling, respectively. Tissue uptake of fluconazole into subcutaneous interstitial fluid was dependent on blood flow with a subcutaneous interstitial fluid-to-plasma partition coefficient (Kp) that was not significantly different from 1.00. Blister fluid concentrations were significantly delayed relative to plasma concentrations and the observed results could not adequately describe the rate of tissue uptake of fluconazole even though fluconazole is a drug with low protein binding.

Acknowledgments

L. Sasongko was supported by Australian Development Scholarship. The assistance of Dr Robert Graham (St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney) in inserting the microdialysis probes is gratefully acknowledged, as is the assistance from staff of the St Vincent's Clinical Trials Centre, St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney. Pfizer Australia kindly provided pure fluconazole and its analogues for the assay.

References

- 1.St Georgiev V. Membrane transporters and antifungal drug resistance. Curr Drug Targets. 2000;1:261–284. doi: 10.2174/1389450003349209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheehan DJ, Hitchcock CA, Sibley CM. Current and emerging azole antifungal agents. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:40–79. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant SM, Clissold SP. Fluconazole. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential in superficial and systemic mycoses. Drugs. 1990;39:877–916. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199039060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Upton RN, Runciman WB, Mather LE. Regional pharmacokinetics. II. Experimental methods. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1990;11:741–752. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2510110902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drusano GL, Preston SL, Van Guilder M, North D, Gombert M, Oefelein M, et al. A population pharmacokinetic analysis of the penetration of the prostate by levofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2046–2051. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2046-2051.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischman AJ, Alpert NM, Livni E, Ray S, Sinclair I, Callahan RJ, et al. Pharmacokinetics of 18F-labeled fluconazole in healthy human subjects by positron emission tomography. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1270–1277. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.6.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thaler F, Bernard B, Tod M, Jedynak CP, Petitjean O, Derome P, et al. Fluconazole penetration in cerebral parenchyma in humans at steady state. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1154–1156. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.5.1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mikamo H, Kawazoe K, Sato Y, Izumi K, Ito T, Ito K, et al. Penetration of oral fluconazole into gynecological tissues. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:148–151. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shrikhande S, Friess H, Issenegger C, Martignoni ME, Yong H, Gloor B, et al. Fluconazole penetration into the pancreas. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2569–2571. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2569-2571.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finley RW, Cleary JD, Goolsby J, Chapman SW. Fluconazole penetration into the human prostate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:553–555. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.2.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeates R, Laufen H, Zimmermann T, Scharpf F. Accumulation of fluconazole in scalp hair. J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;38:138–143. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1998.tb04402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanuma H, Doi M, Yaguchi A, Ohta Y, Nishiyama S, Sekiguchi K, et al. Efficacy of oral fluconazole in tinea pedis of the hyperkeratotic type. Stratum corneum levels. Mycoses. 1998;41:153–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1998.tb00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wildfeuer A, Faergemann J, Laufen H, Pfaff G, Zimmermann T, Seidl HP, et al. Bioavailability of fluconazole in the skin after oral medication. Mycoses. 1994;37:127–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1994.tb00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faergemann J. Pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in skin and nails. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:S14–S20. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brammer KW, Farrow PR, Faulkner JK. Pharmacokinetics and tissue penetration of fluconazole in humans. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:S318–S326. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.supplement_3.s318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ebden P, Neill P, Farrow PR. Sputum levels of fluconazole in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:963–964. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.6.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tucker RM, Williams PL, Arathoon EG, Levine BE, Hartstein AI, Hanson LH, et al. Pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in cerebrospinal fluid and serum in human coccidioidal meningitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:369–373. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.3.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cushing RD, Fulgenzi WR. Synovial fluid levels of fluconazole in a patient with Candida parapsilosis prosthetic joint infection who had an excellent clinical response. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:950. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(97)90166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houang ET, Chappatte O, Byrne D, Macrae PV, Thorpe JE. Fluconazole levels in plasma and vaginal secretions of patients after a 150-milligram single oral dose and rate of eradication of infection in vaginal candidiasis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:909–910. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.5.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbasoglu OE, Hosal BM, Sener B, Erdemoglu N, Gursel E. Penetration of topical fluconazole into human aqueous humor. Exp Eye Res. 2001;72:147–151. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Debruyne D, Ryckelynck JP. Fluconazole serum, urine, and dialysate levels in CAPD patients. Perit Dial Int. 1992;12:328–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haneke E. Fluconazole levels in human epidermis and blister fluid. Br J Dermatol. 1990;123:273–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb01870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang H, Wang Q, Elmquist WF. Fluconazole distribution to the brain: a crossover study in freely-moving rats using in vivo microdialysis. Pharm Res. 1996;13:1570–1575. doi: 10.1023/a:1016048100712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blaser J, Rieder HL, Luthy R. Interface-area to volume ratio of interstitial fluid in humans determined by pharmacokinetic analysis of netilmicin in small and large skin blisters. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:837–839. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.5.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bergan T. Pharmacokinetics of tissue penetration of antibiotics. Rev Infect Dis. 1981;3:45–66. doi: 10.1093/clinids/3.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruun JN, Bredesen JE, Kierulf P, Lunde PK. Pharmacokinetic studies of antibacterial agents using the suction blister method. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1990;74:49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Philip-Joet F, Bruguerolle B, Reynaud M, Arnaud A. Correlations between theophylline concentrations in plasma, erythrocytes and cantharides-induced blister fluid and peak expiratory flow in asthma patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;43:563–565. doi: 10.1007/BF02285104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vermeer BJ, Reman FC, van Gent CM. The determination of lipids and proteins in suction blister fluid. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73:303–305. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12531833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flores-Murrieta F, Granados-Soto V, Hong E. A simple and rapid method for determination of fluconazole in human plasma samples by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Liq Chromatogr. 1994;17:3803–3811. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen HS, Gross JF. Estimation of tissue-to-plasma partition coefficients used in physiological pharmacokinetic models. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1979;7:117–125. doi: 10.1007/BF01059446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown RP, Delp MD, Lindstedt SL, Rhomberg LR, Beliles RP. Physiological parameter values for physiologically based pharmacokinetic models. Toxicol Ind Health. 1997;13:407–484. doi: 10.1177/074823379701300401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McLachlan AJ, Tett SE. Pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in people with HIV infection: a population analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;41:291–298. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1996.03085.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Csajka C, Decosterd L, Buclin T, Pagani J-L, Fattinger K, Bille J, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of fluconazole given for secondary prevention of oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-positive patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57:723–727. doi: 10.1007/s00228-001-0377-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Debruyne D, Ryckelynck JP. Clinical pharmacokinetics of fluconazole. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1993;24:10–27. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199324010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benfeldt E, Serup J, Menne T. Microdialysis vs suction blister technique for in vivo sampling of pharmacokinetics in the human dermis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:338–342. doi: 10.1080/000155599750010210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnetz E, Fartasch M. Microdialysis for the evaluation of penetration through the human skin barrier – a promising tool for future research? Eur J Pharm Sci. 2001;12:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(00)00155-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryan DM, Cars O, Hoffstedt B. The use of antibiotic serum levels to predict concentrations in tissues. Scand J Infect Dis. 1986;18:381–388. doi: 10.3109/00365548609032352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muller M, Stass H, Brunner M, Moller JG, Lackner E, Eichler HG. Penetration of moxifloxacin into peripheral compartments in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2345–2349. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.10.2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muller M, Brunner M, Schmid R, Putz EM, Schmiedberger A, Wallner I, et al. Comparison of three different experimental methods for the assessment of peripheral compartment pharmacokinetics in humans. Life Sci. 1998;62:L227–L234. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shyu WC, Quintiliani R, Nightingale CH, Dudley MN. Effect of protein binding on drug penetration into blister fluid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:128–130. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.1.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruun JN, Ostby N, Bredesen JE, Kierulf P, Lunde PK. Sulfonamide and trimethoprim concentrations in human serum and skin blister fluid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;19:82–85. doi: 10.1128/aac.19.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chosidow O, Dubruc C, Danjou P, Fuseau E, Espagne E, Bianchetti G, et al. Plasma and skin suction-blister-fluid pharmacokinetics and time course of the effects of oral mizolastine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;50:327–333. doi: 10.1007/s002280050117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brunner M, Schmiedberger A, Schmid R, Jager D, Piegler E, Eichler HG, et al. Direct assessment of peripheral pharmacokinetics in humans: comparison between cantharides blister fluid sampling, in vivo microdialysis and saliva sampling. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46:425–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Upton RN. Regional pharmacokinetics. I. Physiological and physicochemical basis. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1990;11:647–662. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2510110802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barchiesi F, Maracci M, Radi B, Arzeni D, Baldassarri I, Giacometti A, et al. Point prevalence, microbiology and fluconazole susceptibility patterns of yeast isolates colonizing the oral cavities of HIV-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50:999–1002. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]