Abstract

Aims

The impact of a short postgraduate course on rational pharmacotherapy planning behaviour of general practitioners (GP) was investigated via a face-to-face interview with 25 GPs working at health centres in Istanbul.

Methods

GPs were randomly allocated to control and intervention groups. Intervention group attended a 3-day-training program preceded and followed by a written exam to plan treatment for simulated cases with a selected indication. The participants’ therapeutic competence was also tested at the post-test for an unexposed indication to show the transfer effect of the course. In addition, patients treated by these GP's were interviewed and the prescriptions were analysed regarding rational use of drugs (RUD) principles at the baseline, 2 weeks and 4 months after the course.

Results

At the baseline there was not any significant difference between the control and intervention groups in terms of irrational prescribing habits. The questionnaires revealed that the GPs were not applying RUD rules in making their treatment plans and they were not educating their patients efficiently. Training produced a significant improvement in prescribing habits of the intervention group, which was preserved for 4 months after the course. However, very low scores of the pretest indicate the urgent necessity for solutions.

Conclusions

Training medical doctors on RUD not only at the under- but also at the postgraduate level deserves attention and should be considered by all sides of the problem including academia, health authorities and medical associations.

Introduction

According to the rules of rational use of drugs (RUD), patients should receive medications appropriate to their specific clinical needs, in doses that meet their own individual requirements for a sufficient length of time, with the lowest cost to them and their community. The above requirements will be fulfilled if the 6-step process of rational prescribing is appropriately followed by (i) defining patient's problem(s) (ii) specifying therapeutic objectives; (iii) choosing the suitable drug(s), correct dosage and optimum duration of use, among the effective and safe treatment alternatives; (iv) starting the treatment by writing a ‘good’ prescription; (v) giving adequate information to the patient, and (vi) monitoring the therapeutic outcome [1–3].

Some of the unwanted consequences of the irrational use of drugs are adverse reactions and drug toxicity due to improper selection of drugs; incomplete treatment of diseases, and development of resistance against antibiotics due to insufficient doses, and/or treatment duration; and higher treatment costs due to the unnecessary use of particularly expensive drugs. A limited number of studies in the field could have revealed that polypharmacy, incorrect application of drugs, inappropriate use of new and expensive products, misuse of antibiotics and injectable forms were among the most common examples of irrational use of drugs at the developing countries [3, 4].

There are several reasons of irrational use of drugs related to educational, sociocultural and economical problems, and administrative and regulatory mechanisms, most of which are interdependent with each other, making the situation more complicated. Irrational use of drugs shows differences from country to country. Developed countries have taken some distance to solve these problems, but greater effort is needed at the developing countries [3–8]. Although the patients, the physicians and other health personnel, regulatory authorities and drug industry are the major partners of the issue, problems concerning the physicians’ prescribing habits seem to be of greatest importance [3, 9].

It has been discussed at a meeting with the contribution of all major parties related to irrational use of drugs issue in Turkey (i.e. representatives from Turkish Ministry of Health, Turkish Medical Association, Turkish Pharmacological Society, and World Health Organization [WHO], and at least one Pharmacology Professor from each Medical Faculty in the country) organized as a part of 1998/99 Midterm Collaboration Program between WHO and Turkish Ministry of Health. The Consensus Report was published in the Bulletin of Turkish Pharmacological Society. It was concluded that well-designed pharmacoepidemiological studies are needed to understand the extent of the problem, but among the major factors underlying was lack of appropriate training of the physicians [10]. Undergraduate medical education focused on rational pharmacotherapy process was one of the solutions offered. Indeed, lectures/clerkships on rational pharmacotherapy have been implemented into the curricula of some medical schools since 1996. However, it was shown that general practitioners in Istanbul do not follow the rational pharmacotherapy process indicating that older graduates are also in need of postgraduate continuous education in this field [11–13]. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the impact of a short postgraduate RUD course focused on pharmacotherapy planning behaviour of general practitioners (GPs) working at primary health care level.

Materials and methods

Study protocol

This study was conducted at Umraniye District of Istanbul in 1999–2000. Participants of the study were 25 GPs working at primary healthcare centres. None of the physicians had received systematic and focused education on RUD previously. They were randomly allocated to control (n = 13) and intervention (n = 12) groups.

The study protocol was schematized in Figure 1. Briefly, a face-to-face interview was done with the GPs asking their knowledge and attitude regarding RUD. The patients who visited these GPs during the selected week were interviewed and the copies of their prescriptions written by these GPs were also collected in order to assess prescription habits of the physicians. Three weeks later, the intervention group attended a short ‘rational pharmacotherapy’ course, and the therapeutic competence of the participants in two selected indications (i.e. upper respiratory tract infections; URTI and hypertension; HT) was assessed before and after the course. No training was given to the control group. An interaction between the groups was not expected because of the geographical location of the health centres.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart

The long-term impact of training was investigated 4 months later by comparing the answers of both groups to a similar physician-questionnaire. Interview with the patients/parents visited both GP groups and prescription analysis were repeated during the selected week, 2 weeks and 4 months after the training course given to the intervention group.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Marmara University School of Medicine.

The choice of study area

The reasons for choosing that particular area were as follows: 1) Primary health care service was being coordinated by the Department of Public Health, Marmara University School of Medicine in collaboration with Istanbul Health Directorate of Turkish Ministry of Health. Therefore, information about the physical conditions of the primary health care centres, number of patients admitting to those centres, major health problems at the region, sociodemographic characteristics of the population and the physicians working there were available [14]. 2) Since the medical students during their Public Health internship period have performed research there since many years, resistance against being evaluated would be less, compared to other areas.

Physician questionnaire

A questionnaire was given to the physicians asking whether they apply principles of RUD for the baseline evaluation (baseline physician questionnaire) and 4 months after the rational pharmacotherapy course (long-term physician questionnaire). Briefly, there were questions about (i) factors influencing their drug choice including the results of history taking, physical examination, and laboratory tests; (ii) efficacy, suitability, safety and cost of the chosen drug(s) among all alternatives (iii) whether they inform their patients about the disease and the treatment; and (iv) whether they recommend nondrug treatment. In addition, they were asked to guess the price of 18 commonly used drugs based on their prescription.

The intervention – rational pharmacotherapy education

Three weeks after the baseline evaluation, the intervention group was invited to attend a 3-day-training program on RUD. The course was designed according to the ‘problem-based Groningen/WHO model’[1]. Several interactive training methods such as small group discussions, role-playing, patient simulations, and objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) were used. An acute (streptococcal tonsillitis) and a chronic (essential hypertension) indication, which are commonly seen by the GPs, were chosen to be discussed during the course. The participants were trained to design a treatment for the above indications due to RUD principles, simply by preparing a P (personal) drug-list, discussing the suitability of the P-drug for a particular patient case, designing non-drug and drug treatment for and educate that patient, and finally monitor the therapeutic outcome.

Pre- and post-course assessment

At the beginning of the course, the participants were asked to design a treatment for simple uncomplicated hypertensive cases (pre-test). The examination was designed as an open (question A1), followed by a structured question (question X). The post-test consisted of an open (question A2) and structured (question Y) question about two simple, uncomplicated hypertensive cases to measure the ‘retention’ effect, and an open question (question B) to design a treatment for an osteoarthritis (unexposed indication) case to measure the ‘transfer’ effect of training. The order of the questions was as A2, B and Y. The ‘open questions’ were simply asking the GPs to treat that particular patient, whereas the ‘structured questions’ were leading the examinee step by step to treat the patient according to the RUD principles.

Scoring pre- and post-tests

The scoring was done by two Pharmacologists independently using the answer keys prepared by a Cardiologist and a Nephrologist for hypertension and two specialists, one from the Department of Rheumatology and the other from the Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation for osteoarthritis, according to the latest guidelines and RUD principles. The mean of the two scores was calculated. If the difference between the two scores was more than 10%, a third Pharmacologist was asked to score the test. The name of the examinee and the date of the examination were masked during scoring. The maximum score was 100. The Pharmacologists were trained to facilitate teaching and score an OSCE at a problem-based rational pharmacotherapy course of Groningen/WHO model.

Patient questionnaire and prescription analysis

Patients who visited the participant GPs of this study and were diagnosed as URTI or HT were interviewed by a face to face questionnaire. In this questionnaire, apart from patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, the GPs’ behaviour regarding RUD principles were evaluated. Such evaluation was done three times, at the beginning of the study (baseline evaluation), 2 weeks (first follow-up) and 4 months after the intervention (second follow-up). The copies of the prescriptions written to these patients at the time of the interview were kept for prescription analysis and the original scripts returned to the patients.

Statistical analysis

All the questionnaires were numbered and the origin of the GP and patient was masked both at the prescriptions and questionnaires to keep the assessors blind.

According to the physician questionnaire, the GPs opinion regarding rational prescribing behaviour of themselves was evaluated by using the following parameters:

If the participant declares that (s)he takes the following information about the patient into consideration in prescribing: 1) age, 2) sex, 3) other drugs being used, 4) hepatic disorder, 5) renal disorder, 6) other chronic diseases, 7) health insurance status, 8) income of the patient – (s)he gets 8 points.

If the participant declares that (s)he chooses the drug(s) among the alternatives according to: 1) efficacy, 2) safety, 3) suitability for the patient, and 4) cost; (s)he gets 4 points.

If the participant knows the price of all 18 drugs asked (s)he gets 18 points. It was considered as correct, when the participant's answer was within the range of ‘the real price ± 10%’.

If the participant declares that (s)he informs the patient about the following related to his/her diagnosis: 1) name, 2) prognosis and 3) potential complications of the disease and 4) the possibility to respond the treatment – (s)he gets 4 points.

If the participant declares that (s)he informs the patient about the following related to the drug(s) prescribed: 1) name, 2) dosage form, 3) dose, 4) use instructions, 5) effect(s), 6) side-effect(s) of the drug(s), 7) warnings and 8) duration of use – (s)he gets 8 points.

Whether or not the participant declares that (s)he:

prescribes without examining the patient;

prescribes upon patients’ request;

always tries to become sure that his/her patient understood the instructions;

asks the patient to repeat what (s)he recalls about the treatment;

always offers nondrug treatment to his/her patients; and

is open to the influence of drug company representatives in his/her drug choice were assessed.

Prescriptions were analysed according to the following criteria:

Legibility: Readability of each prescription (0–3 points);

Format: Writing instructions (0–3 points) and necessary warnings (0–5 points) on the script;

Rationality of drug choice regarding efficacy (0–4 points), safety (0–4 points), suitability (0–4 points), and cost (0–4 points);

Number of drugs per prescription;

Cost: The price list prepared by Turkish Ministry of Health was used and the prices were converted to US Dollars.

By using the patient questionnaires, the percentage of patients examined, informed by the GPs about his/her diagnoses, drugs, side-effects, warnings, instructions, nondrug treatment and asked to repeat their treatment instructions by the GPs were calculated.

Data were analysed by SPSS for Windows version 11.0. Fisher's exact chi-square, Mann–Whitney U, Wilcoxon, Mc Nemar, One Way Anova, and Student's t-tests were used for data analysis. p <0.05 was the level of statistical significance.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the subjects

There were 12 GPs at the intervention and 13 GPs at the control group. No statistical significance observed between the groups in terms of mean age, sex, graduation year and working experience at primary health care facilities [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the subjects. There was no statistically significant difference between groups

| Intervention group (n = 12) | Control group (n = 13) | |

|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 75 | 69 |

| Age (year) (mean ± s.d.) | 33.3 ± 4.5 | 33.2 ± 6.4 |

| Working experience after graduation (year) (mean ± s.d.) | 10.0 ± 4.9 | 9.5 ± 4.7 |

| Working experience at primary health care level (year) (mean ± s.d.) | 8.8 ± 4.8 | 8.1 ± 4.2 |

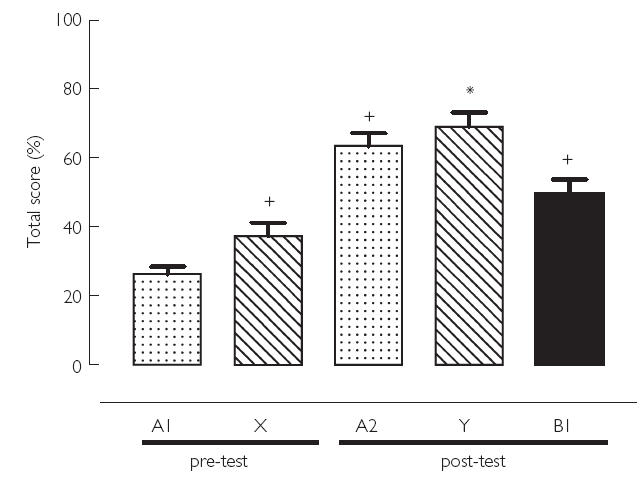

Effect of RUD course on therapeutic competence of the GPs in the intervention group [Figure 2]

Figure 2.

Pre- and post –test results. Maximum total score was 100; +, p <0.05 compared with A1; *, p <0.05 compared with X. A1: hypertension ‘open’ ( ), X: hypertension ‘structured’ (

), X: hypertension ‘structured’ ( ), A2: hypertension ‘open’ (

), A2: hypertension ‘open’ ( ), Y: hypertension ‘structured’ (

), Y: hypertension ‘structured’ ( ), B1: osteoarthritis ‘open’ (

), B1: osteoarthritis ‘open’ ( )

)

The participants got very low pretest scores for designing pharmacotherapy for two uncomplicated essential hypertension cases (26.2 ± 2.3; range: 14–42, for the open question; and 37.3 ± 3.9; range: 15–58 for the structured question). However, the mean score of the pretest structured question was significantly higher than the open question (X vs A1; p <0.05) indicating that guidance through RUD principles improved prescribing.

The post-test results (A2 and Y), when compared with the pretest (A1 and X), showed the benefit of training on pharmacotherapy planning skills of the GPs. To reveal the retention effect of training, the mean scores of pretest and post-test open hypertension questions (A1 and A2) were compared, and the latter was found to be significantly higher (A1 vs A2; p <0.05). Not only the GPs’ therapeutic decision making skills, but also their knowledge about hypertension and its treatment has improved during the course, and therefore, there was also a significant increase in the mean score of the structured hypertension question at the post-test compared with that of pretest (X vs Y; p <0.05). Furthermore, the significant difference between the scores of open and structured questions, observed at the pretest, disappeared at the post-test, also showing the benefit of training (A2 vs Y; p >0.05). Since the mean post-test score for question B (the indication unexposed during the course) was significantly higher than question A1 (A1 vs B; p <0.05), the physicians seem to transfer their skills acquired by training to another indication, which was not included in the course program.

The participants’ oral and written feedback about the course was highly impressive. Briefly, they said that the course was well organized, the learning goals were achieved, and it was obviously very useful for their medical practice. All of them gave full score as a final evaluation of the course and stated that such training programs are essential as a part of continuous medical education and should be given repeatedly to all GPs working at primary health care level.

Physician-questionnaire

The participants’ scores regarding application of rational pharmacotherapy process, according to the physician questionnaire and comparison of GPs at control and intervention group in terms of several steps of rational pharmacotherapy process were shown at Tables 2 and 3. At the baseline evaluation, the intervention and control groups were not found to be significantly different from each other in terms of applying major RUD rules.

Table 2.

The participants’ scores (mean ± s.d.) regarding application of rational pharmacotherapy process, according to the physician questionnaire.ap < 0.05, intervention vs control;b p < 0.05, baseline vs long-term

| Intervention Group (n = 12) | Control Group (n = 13) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RUD rule | Max. score | Baseline | Long-term | Baseline | Long-term |

| Taking patient's history into consideration in drug choice | 8 | 4.9 ± 1.6 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 4.9 ± 0.2.2 | 5.8 ± 2.1 |

| Comparing available drug alternatives due to efficacy, safety, suitability and cost | 4 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 2.4 ± 1.2 |

| Informing the patient about the disease | 4 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 0.8 |

| Informing the patient about the drug(s) | 8 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 5.2 ± 1.3 | 4.6 ± 2.5 | 4.3 ± 1.7 |

| Knowing the price of the drug(s) | 18 | 1.3 ± 1.6 | 4.0 ± 1.9 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 0.8 |

Table 3.

Comparison of GPs at control and intervention groups in terms of several steps of rational pharmacotherapy process

| Percentage of GPs who said ‘yes’ and ‘sometimes’ to the questions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Group (n= 12) | Control Group (n = 13) | |||

| Questions | Baseline | Long-term | Baseline | Long-term |

| Do you prescribe without examining the patient? | 58.3 | 41.7 | 69.2 | 76.9 |

| Do you prescribe upon the patients’ request? | 83.3 | 66.7 | 61.5 | 84.6 |

| Do you do everything to make your patient understand all the information and instructions about the disease and the treatment? | 50.0 | 91.7 | 53.8 | 61.5 |

| Do you ask your patient to repeat the instructions about his/her treatment? | 58.3 | 91.7 | 69.2 | 84.6 |

| Do you recommend nondrug treatment? | 75.0 | 91.7 | 84.6 | 84.6 |

The participants declared that they use only 4.9 of 8 parameters regarding patient's history in order to choose the most suitable drug treatment [Table 2]. Among these, the most commonly noticed information was age of the patient (by about 84% of the participants in both groups), while the least common one was sex (by 17 and 39% of the participants in control and intervention groups, respectively). Not all but only 61.5 and 75% the GPs told that they ask other drugs used by their patients.

In order to choose the best drug among alternatives, the major four criteria were taken into consideration by the following percentages of the participants in the control and intervention groups, respectively: efficacy, 100 and 81.8%, safety, 69.2 and 45.5%, suitability, 46.5 and 36.4%, cost, 38.5%, and 45.5%. Unfortunately, there were no GPs declaring that (s)he routinely uses all of these criteria, with the mean scores of 1.9 ± 1.2 (control) and 2.6 ± 1.1 (intervention). Even though 38.5 and 45.5% of them said that they consider cost of the treatment, they could know the price of only 1.3 ± 1.6 (control) and 1.5 ± 0.6 (intervention) of 18 commonly prescribed drugs [Table 2]. More than half of the participants told that they do not tell the name and the expected pharmacological/therapeutic effect(s) of the drug(s) to the patient, and even the percentage of GPs telling the drug use instructions could not reach 100%. Similarly, only half of the participants declared that they always explain the diagnosis.

After training, significant improvement has been observed in the intervention group except that (i) the GPs showed resistance against informing the patient thoroughly about the diagnosis, prognosis, complications and the possibility of therapeutic success; and (ii) paying attention to the particular aspects of patient's history in making treatment decision improved, but could not reach the level of significance [Table 2].

At the baseline evaluation, at both groups, more than half of the GPs declared that they prescribe without examining and upon patients’ request; 1/3–1/2 of them said that they do not spend extra effort to make their patient understands the information delivered and the instructions given; only half of the participants told that they ask them to repeat the instructions to be sure whether they understood correctly; about 1/4 of the GPs responded negative to the questions about recommending nondrug treatment [Table 3]. After the rational pharmacotherapy course, the intervention group showed prominent improvement in terms of applying the above principles, particularly trying to educate the patient to make him/her understand the instructions and recommending nondrug treatment [Table 3], although the differences could not reach the level of statistical significance possibly because of small number of participants in each group.

Prescription analysis [Table 4]

Table 4.

Statistical analysis of the prescriptions in terms of legibility and rationality. Number of prescriptions analysed: Control group: 280 at baseline, 176 at 1st follow-up, 205 at 2nd follow-up; Intervention group: 385 at baseline, 264 at 1st follow-up, 192 at 2nd follow-up. P < 0.05: aintervention vs control; bintervention follow-up vs intervention baseline; cintervention 1st follow-up vs intervention 2nd follow-up

| Max. score | Follow-up | Intervention (mean± s.d.) | Control (mean± s.d.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legibility | 3 | Baseline | 1.15 ± 0.70 | 1.25 ± 0.83 |

| 1st | 2.92 ± 0.40ab | 2.63 ± 1.07 | ||

| 2nd | 2.66 ± 0.78abc | 1.69 ± 1.10 | ||

| Writing drug use instructions on prescription | 3 | Baseline | 0.88 ± 0.48a | 0.99 ± 0.54 |

| 1st | 2.81 ± 0.46ab | 0.94 ± 0.60 | ||

| 2nd | 2.28 ± 0.95abc | 1.03 ± 0.93 | ||

| Writing important warning(s) on prescription | 5 | Baseline | 0.08 ± 0.30a | 0.02 ± 0.16 |

| 1st | 2.52 ± 2.03ab | 0.06 ± 0.28 | ||

| 2nd | 2.14 ± 1.95abc | 0.30 ± 0.82 | ||

| Choosing rational drug(s) | 12 | Baseline | 5.0 ± 2.27a | 5.31 ± 2.17 |

| 1st | 9.56 ± 2.27 | 6.67 ± 1.88 | ||

| 2nd | 8.97 ± 2.03ab | 6.93 ± 1.69 | ||

| Number of drugs per prescription | Baseline | 3.48 ± 1.10 | 3.45 ± 1.0 | |

| 1st | 2.76 ± 1.11ab | 3.50 ± 1.07 | ||

| 2nd | 2.93 ± 1.21ab | 3.33 ± 1.19 | ||

| Total costs per prescription ($US). | Baseline | 27.35 ± 38.92 | 26.81 ± 24.12 | |

| 1st | 21.12 ± 33.82a | 28.72 ± 22.43 | ||

| 2nd | 26.05 ± 34.21 | 31.96 ± 31.57 |

A total of 385, 264 and 192 prescriptions written by the intervention group during the baseline, 1st follow-up and 2nd follow-up evaluation periods were analysed. The corresponding prescription numbers of the control group were 280, 176 and 205, respectively. At the baseline, differences regarding the application of RUD principles between the intervention and control groups were considered to be insignificant. After the training, the prescriptions of the intervention group showed significant improvement in all parameters at the first follow-up (P < 0.05 for intervention vs control, and intervention baseline vs intervention 1st follow-up), except that the mean total cost per prescription of the intervention group was significantly lower than that of the control group, but the difference could not reach the level of significance when compared with its own baseline value. Improvement persisted at the 2nd follow-up except for cost per prescription, which returned to baseline in the intervention group. The prescription costs of the control group were even higher than baseline at the 2nd follow-up, but the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant. Slight improvements have also been detected in the control group regarding legibility, rational drug choice and writing important warnings on the script, possibly due to the stimulating effect of the baseline physician questionnaire.

Patient questionnaire

Three different patient populations were interviewed at the baseline (381 and 260 patients for intervention and control groups, respectively), 1st (244 and 167 patients for intervention and control groups, respectively) and 2nd follow-up (184 and 192 patients for intervention and control groups, respectively) evaluation periods. There was no statistically significant difference between these groups regarding their sex, age and educational status [Table 5]. There was no statistically significant difference between the intervention and control groups regarding the percentage of patients examined, informed about his/her diagnoses, drugs, side-effects, warnings, instructions, nondrug treatment and asked to repeat their treatment instructions by the GPs [Table 6]. All parameters significantly improved in the intervention group after training (1st and 2nd follow-up) while such changes were not detected in the control group [Table 6]. However, there was slight but insignificant regression at the 2nd follow-up of the trained GPs regarding number of patients informed about their drugs, side-effects and instructions, and those asked to repeat the instructions.

Table 5.

Sociodemographic characteristics of attendants at baseline study (P > 0.05, intervention vs control group in all parametres)

| Intervention (%) (n = 381) | Control (%) (n = 260) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 71.1 | 67.7 |

| Age | ||

| Under 25 | 19.9 | 16.6 |

| 25–44 | 46.5 | 45.6 |

| 45–64 | 23.4 | 29.7 |

| Upper 64 | 10.2 | 8.1 |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 15.8 | 12.3 |

| Primary school | 47.5 | 49.2 |

| High school | 24.9 | 24.6 |

| University | 11.8 | 13.9 |

Table 6.

Statistical analysis of the patient questionnaire. Number of patient questionnaire analysed: Control group: 260 at baseline, 167 at 1st follow-up, 192 at 2nd follow-up; Intervention group: 381 at baseline, 244 at 1st follow-up, 184 at 2nd follow-up. P < 0.05: aintervention vs control; bintervention follow-up vs intervention baseline; cintervention 1st follow-up vs intervention 2nd follow-up

| Follow-up | Intervention (%) | Control (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients examined by their GP’s. | Baseline | 68.0 | 66.3 |

| 1st | 77.8ab | 55.4 | |

| 2nd | 76.0a | 60.3 | |

| Number of patients informed by the GPs about the disease. | Baseline | 58.0 | 57.9 |

| 1st | 84.4ab | 62.4 | |

| 2nd | 87.9ab | 49.7 | |

| Number of patients informed by the GPs about drugs (s). | Baseline | 48.9 | 45.3 |

| 1st | 80.1ab | 40.1 | |

| 2nd | 68.7abc | 42.0 | |

| Number of patients informed by the GPs about the drug(s)′ side-effect(s). | Baseline | 7.7 | 7.8 |

| 1st | 37.2ab | 1.2 | |

| 2nd | 21.5abc | 6.0 | |

| Number of patients informed by the GPs about the warning(s). | Baseline | 18.9 | 13.5 |

| 1st | 38.0ab | 13.9 | |

| 2nd | 37.1ab | 15.8 | |

| Number of patients informed by the GPs about the drug(s)′ instruction(s). | Baseline | 44.9 | 45.7 |

| 1st | 92.1ab | 51.5 | |

| 2nd | 71.7abc | 44.0 | |

| Number of patients informed by the GPs about non drug treatment(s). | Baseline | 19.8 | 15.8 |

| 1st | 40.2ab | 17.6 | |

| 2nd | 49.1ab | 14.9 | |

| Number of patients who made the GPs repeat the instructions about treatment. | Baseline | 9.5 | 5.5 |

| 1st | 57.8ab | 4.2 | |

| 2nd | 42.9abc | 6.7 |

Discussion

The results of the baseline evaluation of the present study revealed that the GPs do not apply RUD rules in making their treatment plans and they were not educating their patients efficiently, which is an essential component of RUD. Indeed, whenever a physician chooses the therapeutic objectives for a particular patient after diagnosing the disease, a close look at the patient's history is required to assess the suitability of the chosen drug(s) for that particular case [15]. Unfortunately, the participants of this study declared that they use only 4.9 of 8 parameters in this respect. While any drug added to the prescription is known to increase the risk of adverse effects and drug interactions, the present study revealed that only 1/4 of the GPs asks other drugs used by their patients before prescribing. In addition, when economical shortage of the families admitting to a health centre and limited resources reserved for drug expenses in Turkey are concerned, it becomes more important to recommend optimum number of medications [16–18].

It is essential to compare the alternative drug choices according to their efficacy, safety, suitability and cost. However, the baseline prescription analysis revealed that the drug choices were hardly rational. Furthermore, there were no GPs declaring that (s)he routinely uses all of these criteria at the precourse physician questionnaires. They all were likely to prescribe depending on the efficacy, whereas less than half of the participants were thinking about the suitability and cost of the drugs. Cost of the treatment has indeed great importance from the economical standpoint, not only in developing but also developed countries no matter whether the government or insurance systems cover drug expenses. Furthermore, it has been well documented that the most expensive medication are rarely the best choices [1, 19, 20]. Interestingly, in the present study, almost all of the participants were ignorant about treatment costs. They could know the price of only about 1.5 of the 18 commonly used drugs correctly. This finding is particularly important for a country like Turkey with a very limited budget for health, but has to spend 1/3 of it for mostly irrationally chosen medications. It is another fact that one third of the population has no health insurance in Turkey [21]. In most well developed countries, there are continuously updated databases for prescription expenses and feedback information is being sent to the physicians regularly. Such a regulation is expected to reduce treatment costs efficiently [22–24].

Patient compliance is an essential component of therapeutic success, however, poor compliance is usual. Although the educational and intellectual status of the patient, their expectations from the physician, the length of time the physician allocates for the patient, and several other factors determine patient compliance; it is the doctor's responsibility to educate the patient in terms of drug and nondrug treatment instructions and be sure that the patient understands everything. Therefore, drug information, use instructions and warnings should be given very carefully and the physician must be certain that the patient comprehends the given information accurately. The simplest way to do this is to ask the patient to repeat the physician's instructions [1, 15]. However, while half of the participants stated to do so, less than 10% of the patients declared that they were required to repeat drug use instructions, in the present study.

Keeping in mind that at primary health care level in Turkey, the GPs would not spend enough time for each patient and the educational status of the population they serve for is not high enough, the patients could even not know why these drugs were recommended if they were not informed by the doctor. Under these circumstances, high compliance rates cannot be expected among these patients. Unfortunately, at the baseline evaluation of the present study, only 58–69% of the GPs declared that they spend extra effort to make their patients understand the instructions. More than half of the participants told that they do not tell the name and the expected pharmacological/therapeutic effect(s) of the drug(s) to the patient, and even the percentage of GPs telling the drug use instructions could not reach 100%. Indeed, patient questionnaires showed that these percentages are much lower in real life. Similarly, most of the participants declared that they do not always feel the necessity of explaining the diagnosis. In fact, it is the patients’ right to know every detail about their health and well being. Furthermore, the patients have their own expectations and they are in need to be satisfied. Therefore, the patient should be the real partner of the doctor in making the treatment plans to increase their belief in their doctor and treatment, thus to improve patient compliance [1].

Non-drug treatment as a part of RUD, not only should accompany drug treatment in most indications, but also might alone be the first choice in some diseases/conditions such as mild hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes and obesity [25–29]. However, 1/4 of the participants responded the question about recommending nondrug treatment to their patients negatively; and less than 20% of them actually informed their patients in this respect.

As stated above, patients’ expectation leads the doctors to prescribe irrationally [30]. The sources of drug information for patients obviously are relatives, neighbours and more likely wrong and/or misleading health news on daily newspapers and/or TV. In fact, 60–80% of the participants told that they do prescribe upon their patients’ request. The major reason for which the GPs to prescribe upon patient's request easily is likely to be the high number of patients admitting to the health centres for refill prescriptions originally written by specialists. This also might be the reason why more than half of the GPs tell that they prescribe even without examining the patient. The extent of this problem might be much broader than appeared; thus, more thorough and systematic evaluation is needed on the matter.

The participants told that they mostly apply RUD rules. However, the objectivity of the answers to the precourse questionnaire carries some doubt, not only because apparently patient questionnaires were contradictory with general GPs declaration about their attitude regarding rational prescribing, but also because the mean score of the pretest of GPs at the intervention group could not exceed 40. These scores clearly revealed that for a common chronic disease like hypertension, which might and should be monitored at primary health care level, the GPs failed to plan a rational pharmacotherapy. Furthermore, baseline analysis demonstrated that the prescriptions were very poor in terms of RUD principles such as rationality of drug choice, writing drug use instructions and warnings on the script and legibility.

Irrational prescribing is common in many countries, and computer based databases have been developed to monitor irrational drug use [17, 23, 31, 32]. Among solution proposals, education of both doctors and patients is of the greatest importance [33, 34]. It has been reported that rational pharmacotherapy education via interactive teaching methods such as problem-based learning at the medical schools might be effective in the prevention of irrational prescribing habits of their graduates [35, 36]. For example, at a study about a problem-based rational pharmacotherapy course for medical students similar to that used in the present study, it was shown that compared with control students rational choices of trained students increased significantly for all aspects of drug choice, and almost all patient problems used in the study, whether or not they had been discussed (retention and transfer effects) [37]. The impact of such a course using Groningen/WHO rational pharmacotherapy model was investigated at an international multicentral randomized controlled study and this approach was reported to be an efficient way of teaching rational pharmacotherapy [36].

In the present study, GPs in the intervention group attended a three-day rational pharmacotherapy course. Significant improvement in all aspects of rational prescribing attitudes of the GPs has been demonstrated not only by physician questionnaire, but also interviewing with their patients and analysing their prescription. Similarly, in a controlled pre/post-test study in Yemen, medical students (trained by Groningen/WHO model) and postgraduate medical residents (graduated without such a training) were compared and it was concluded that proper training, i.e. ‘immunizing’ future doctors using problem-based pharmacotherapy teaching, was an efficient way of teaching rational prescribing [38]. Under the title of Drug Education Project (DEP; 1993), a group of investigators have reported that RUD training improved prescribing in asthma and urinary tract infections in Holland, Sweden, Norway, Germany and Slovakia [39–42]. Another report from Switzerland compared the beneficial effect of 4 different educational methods on rational pharmacotherapy in asthma at primary health care level [43].

More importantly, the improvement was maintained for at least 4 months after training in this study. One of the few significant failures regarding the long-term impact of training was about knowing the cost of the drugs by the GPs and total costs of the prescriptions. A decline was detected in the cost per prescription after the training in the intervention group ($27.3 in the baseline, $21.1 in the first follow-up); but it returned towards baseline at the 2nd follow-up, an effect which might be attributed to the high inflation rates in Turkey [44]. High inflation rates might also be a reason for the GPs for not being aware of the cost of the drugs.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that GPs working at health centres were not applying RUD rules in making their treatment plans and they were not educating their patients efficiently. Very low scores of the pretest indicate the urgent necessity for solutions. The short postgraduate training program produced a significant improvement in prescribing habits of these physicians, which was reserved for at least 4 months after the course. Therefore, continuous medical education for GPs on RUD, developing ways of increasing the level of social awareness to this issue and patients’ expectations from physicians should be considered by all sides of the problem, academia, health authorities, medical associations, drug companies, and nongovernmental organizations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Yunus Emre Kocabasoglu and Dr F. M. Haaijer-Ruskamp for their great help in designing the study, Dr Serhan Tuglular, Dr Ali Serdar Fak, Dr Haner Direskeneli and Dr Gülseren Akyüz for their help in preparation of the pre/post test answer keys, and Ece Iskender for her help in video recordings of OSCE.

The authors will be happy to forward further information about the study design and material used (i.e. case scenarios, questionnaires, etc.) to anyone who would like to perform a similar study at a different setting if (s)he will contact with the correspondending author, Dr Sule Oktay (suleok@omega-cro.com.tr).

References

- 1.De Vries TPGM, Henning RH, Hogerzeil HV, Fresle DA. Geneva: WHO/Action programme on essential drugs; 1994. Guide to Good Prescribing. [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Vries TPGM. Presenting clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. a problem based approach for choosing and prescribing drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;35:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb04185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Grand A, Hogerzeil HV, Haaijer-Ruscamp FM. Intervention research in rational use of drugs: a review. Health Policy Planning. 1999;14:89–102. doi: 10.1093/heapol/14.2.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ro Laing Hogerzeil HV, Ross-Degnan D. Ten recommendations to improve use of medicines in developing countries. Health Policy Planning. 2001;16(1):13–20. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon DH, Houten LV, Glynn RJ, et al. Academic detailing to improve use of broad-spectrum antibiotics at an academic medical center. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1897–1902. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jernigan DB, Cetron MS, Breiman RF. Minimizing the impact of drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (DRSP) JAMA. 1996;275:206–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nilsson G, Hjemdahl P, Hassler A, Vitols S, Wallen NH, Krakau I. Feedback on prescribing rate combined with problem-oriented pharmacotherapy education as a model to improve prescribing behaviour among general practitioners. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;56:843–848. doi: 10.1007/s002280000242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergman U, Popa C, Tomson Y, Wettermark B, et al. Drug utilization 90%- a simple method for assessing the quality of drug prescribing. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:113–118. doi: 10.1007/s002280050431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO./DAP. Geneva. World Health Organization; 1994. Injection use and practices in Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oktay S. Final report of the workshop on the role of pharmacotherapy education and clinical pharmacology in the use of Rational Drug Use Principles. Kizilcahamam, Ankara, Turkey, 28–29 September 1999. Turkish Pharmacology Bulletin. 1999:57. Sept–Oct: [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akici A, Kalaça S, Ugurlu MÜ, Çali S, Oktay S. Evaluation of rational drug use of general practitioners’ in management of elderly patients. Turk J Geriat. 2001;4(3):100–105. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akici A, Kalaça S, Ugurlu MÜ, Gönül N, Oktay S. Evaluation of knowledge and attitude for rational use of drug in general practitioners. Continuous Med Education J (Sürekli Tip Egitimi Dergisi; STED) 2002;7(2):253–257. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akici A, Altunbas HZ, Kalaça S, Ugurlu MÜ, Çali S, Oktay S. Prescribing habits of general practitioners in hypertension in Istanbul. 5th Congress of the European Association for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics; Odense, Denmark. 2001. (Pharmacol Toxicol 2001 Supplement, September 12–15, 1 (89): 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Çali S. 1999. Ümraniye; Beliefs and Values of Men and Women About Contraceptive Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO. Trainer's Guide. Accra, Ghana; 1998. Promoting rational drug use. 15–27 October. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bijl D, Sonderen EV, Haaijer-Ruscamp FM. Prescription changes and drug costs at the interface between primary and specialist care. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:333–336. doi: 10.1007/s002280050469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isaksen SF, Jonassen J, Malone DC, Billups SJ, Carter BL, Sintek CD. Estimating risk factors for patients with potential drug-related problems using electronic pharmacy data. Ann Pharmacotherapy. 1999;33:406–412. doi: 10.1345/aph.18268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veehof LJG, Stewart RE, Meyboom -d, eJong B, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Adverse drug reactions and polypharmacy in the elderly in general practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1999a;55:533–536. doi: 10.1007/s002280050669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mylotte JM. Antimicrobial prescribing in lon-term care facilities: Prospective evaluation of potential antimicrobial use and cost indicators. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27:10–19. doi: 10.1016/s0196-6553(99)70069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davey PG, DoddT Malek M, MacDonald T. Pharmacoeconomics and drug precribing. In: Speight TM, Holford HG, editors. Avery's Drug Treatment. 4. New Zelland: Adis Press; 1997. pp. 393–422. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soyer A. [How Could World, Turkey, Health and Medical Environment be foreseen for the period of 20022000–20?] Ankara: TTB; [Health Services in Turkey, Health, Physicians and Inequalities; looking into the future] pp. p 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan RDJ, Sutters CA, Livesley B. Cost-Effective prescribing in Elderly People. Pharmacoeconomics. 1992;1(6):387–393. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199201060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez LAG, Gutthan SP. Use of UK general practice research database for pharmacoepidemiology. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;45:419–425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell SM, Cantrill JA, Roberts D. Prescribing indicators for UK general practice: Delphi consultation study. Br Med J. 2000;321(7258):425–428. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO Hypertension Guidelines Subcommittee. World Health Organization-International Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension. J Hypertension 1999. 1999;17:151–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Midgley JP, Matthew AG, Mmath CMTG, Logan AG. Effect of reduced dietary sodium on blood pressure. JAMA. 1996. pp. 1590–1597. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, et al. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons. JAMA. 1998;279:839–846. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.11.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grimmatal HR, Flack JM, Grandits GA, et al. Long-term effects on plasma lipids of diet and drugs to treat hypertension. JAMA. 1996;275:1549–1556. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530440029033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meltzer S, Leiter L, Daneman D, et al. clinical practice guidelines for the management of diabetes in Canada. CMAJ 1998. 1998;159:S1–S29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mangione-Smith R, McGlynn AA, Elliott MN, Krogstad P, Brook RH. The relationship between perceived parental expectations and pediatrician antimicrobial prescribing behavior. Pediatrics. 1999;103:711–718. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.4.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bjerrum L, Rosholm JU, Hallas J, Kragstrup J. Methods for estimating the occurrence of polypharmacy by means of a prescription database. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;53:7–11. doi: 10.1007/s002280050329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bjerrum L, Sogaard J, Hallas J, Kragstrup J. Polypharmacy: correlations with sex, age and drug regimen. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:197–202. doi: 10.1007/s002280050445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walley T, Bligh J. The educational challenge of improving prescribing. Postgrad Edu General Prac. 1993;4:50–54. [Google Scholar]

- 34.WHO./DAP. Geneva: World Health Organization; How to investigate drug use in health facilities: selected drug use indicators. WHO, 1993/DAP/931. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hogerzeil HV. Promoting rational prescribing: an international perspective. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;9:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb04402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Vries TPGM, Henming RH, Hogerzeil HV, Bapna JS, Bero L, Kafle KK, Mabadeje AFB, Santoso B, Smith AJ. Impact of a short course in pharmacotherapy for undergraduate medical students: an international randomized controlled study. Lancet. 1995;346:1454–1457. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92472-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Vries TPGM. Presenting clinical pharmacology and therapeutics: evaluation of a problem based approach for choosing drug treatments. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;35:591–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb04187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hassan NAGM, Abdulla AA, Bakathir HA, Al-Amoodi AA, Aklan AM. TPGM de Vries. The impact of problem-based pharmacotherapy training on the competence of rational prescribing of Yemen undergraduate students. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;55:873–876. doi: 10.1007/s002280050710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Veninga CCM, Lagerlov P, Wahlström R, Muskova M, Denig P, Berkhof J, Kochen MM, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Evaluating an educational intervention to improve the treatment of asthma in four European countries. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1254–1262. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9812136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veninga CCM, Lundborg CS, Lagerlov P, Hummers-Pradier E, Denig P, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections: exploring differences in adherence to guidelines between three European countries. Ann Pharmacother. 2000a;34:19–26. doi: 10.1345/aph.19068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Veninga CCM, Denig P, Zwaagstra R, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Improving drug treatment in general practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000b;53:762–772. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lagerlov P, Veninga CCM, Muskova M, Hummers-Pradier E, Lundborg CS, Andrew M, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Asthma management in five European countries. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tomson Y, Hasselström J, Tomson G, Aberg H. Asthma education for Swedish primary care physicians- a study on the effects of ‘academic detailing’ on practice and patient knowledge. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;53:191–196. doi: 10.1007/s002280050361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The Pharmaceutical Journal News. Internet speeds reimbursement for Turkish pharmacies. The Pharmaceut J. 2000;265(7111):p285. [Google Scholar]