Abstract

Aim

To assess the effects of the motilin receptor antagonist RWJ-68023 on basal and motilin-stimulated proximal gastric volume.

Methods

Eighteen healthy male volunteers received RWJ-68023 in two different doses or placebo for 135 min. After 45 min, subjects received a motilin infusion for 90 min. Proximal gastric volume was measured with a barostat at constant pressure and during isobaric distensions. Abdominal symptoms were scored using visual analogue scales. Motilin and RWJ-68023 concentrations were assessed by radioimmunoassay and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, respectively.

Results

Both dosages of RWJ-68023 were safe and well tolerated. The most common adverse events were of gastrointestinal origin. RWJ-68023 did not affect basal proximal gastric volume, but the high-dose RWJ-68023 reduced the contractile effect of motilin on the stomach. This antagonizing effect of RWJ-68023 was only significant (P = 0.014) during the distension procedure.

Conclusions

The RWJ-68023 doses used in this study were selected to accomplish plasma concentrations that would block the motilin effect entirely. However, the antagonizing effect of RWJ-68023 was partial and only present when the tonic condition of the stomach was modulated by motilin.

Keywords: antagonist, human and barostat, motilin, stomach

Introduction

Motilin is a gastrointestinal (GI) peptide synthesized and released by enterochromaffin cells in the proximal small intestine [1]. Motilin is involved in the regulation of interdigestive and postprandial GI motility [2, 3]. Disturbed GI motility is a feature observed in functional bowel disorders such as functional dyspepsia (FD) [4–6] and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [7, 8]. In healthy volunteers, motilin decreases postprandial gastric volumes similarly to the impaired postprandial relaxation observed in patients with FD [3, 5]. The disturbed GI motility observed in patients’ IBS coincides with altered motilin levels [9–11]. Therefore, it may be suggested that disturbances in the regulatory function of motilin may be associated with these clinical entities [12, 13].

To explore whether motilin antagonism may be a useful therapeutic intervention in these disorders, a study was performed to investigate the effects of RWJ-68023, a selective, nonpeptide motilin receptor antagonist (Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development, Raritan, NJ, USA) in healthy volunteers. Although dyspeptic symptoms are usually related to feeding, RWJ-68023 was studied in the fasted state. Many mechanisms (neuronal as well as hormonal regulation) are involved in the postprandial relaxation of the stomach; as the present study aimed to investigate pure motilin-antagonizing properties of RWJ-68023, the healthy volunteers were studied in the fasted state. In addition, the motilin effect on the stomach in the fasted state has been well described in both healthy volunteers and dyspeptic patients [14].

Preclinical studies have shown that RWJ-68023 (molecular weight 708.5 Da) potently inhibits binding of radiolabelled motilin to membranes prepared from rabbit antrum, duodenum and colon with inhibition constants (Ki) of 9, 82 and 18 nM, respectively. The binding affinity of RWJ-68023 has been evaluated in preparations containing either endogenous or cloned human motilin receptors; RWJ-68023 strongly inhibits the binding of motilin to both the endogenous (IC50 = 32 nM) and cloned human motilin receptor (IC50 = 114 nM) [15].

In vitro studies of rabbit duodenal smooth muscle strips have shown that RWJ-68023 antagonizes motilin-induced contractions with a Ki of 89 nM. RWJ-68023 appeared to be specific for the motilin receptor since it antagonizes neither acetylcholine-induced contractions in rabbit duodenal smooth muscle nor potassium-induced contractions in rabbit aorta in vitro.

Pharmacokinetic studies in rats and dogs have shown that after intravenous administration, RWJ-68023 was widely distributed and slowly eliminated with a terminal half-life of 3.2–6.6 h in rats and 6.1–12.2 h in dogs. In vitro studies in rat and human hepatic S9 fractions suggested that RWJ-68023 was not extensively metabolized.

The doses of the first human entry of RWJ-68023 (45 min i.v. administration of a dose range of 0.125–1.125 mg kg−1) appeared to be safe and well tolerated. Drug exposure, expressed as maximal concentration (Cmax = 197.6–2540.6 pmol ml−1) and area under the curve (AUC = 310.5–3387.4 pmol h−1 ml−1) increased in a dose-related manner.

Limited information is available about the effects of motilin antagonists in humans, and all compounds evaluated thus far are peptides [16, 17]. The motilin antagonist GM-109 was shown to competitively inhibit contractions induced by porcine motilin in rabbit isolated duodenum strips, and in vivo GM-109 completely abolished the gastric antrum and duodenal motor responses induced by [Leu13]motilin [18, 19]. The present study is the first to investigate the pharmacodynamic effects of a nonpeptide motilin receptor antagonist. The aim of the current study was to investigate the motilin-antagonistic effects of RWJ-68023 and safety in healthy male volunteers. The RWJ-68023 effects were assessed on basal proximal gastric volume, as well as on motilin-challenged proximal gastric volume. Based on preclinical and clinical pharmacological data, the targeted plasma concentrations of RWJ-68023 (254.1 pmol ml−1 and 2540.6 pmol ml−1) selected in the present study were multiples of the IC50 and were expected to have motilin antagonizing activity, with receptor binding of approximately 90–100%.

Methods

Experimental design

The study was carried out using a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, three-way crossover design. The Medical Ethics Committee of the Leiden University Medical Centre approved the study protocol. The study was performed according to Good Clinical Practice and International Conference of Harmonization guidelines.

Subjects

Twenty-four male volunteers (mean age 29 years, range 18–45 years) participated in the study after having given written informed consent. Subjects were eligible if they were healthy as assessed by a full medical screening. They were excluded if they had a history of GI symptoms, abdominal surgery, or if they used regular medication. At screening a blood sample for genotyping for cytochrome P450 (CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and NAT2) was taken to determine a potential influence of cytochrome P450 polymorphisms on pharmacokinetics of RWJ-68023 and motilin.

Barostat

An electronic barostat device (Synectics Visceral Stimulator; Synectics Medical, Stockholm, Sweden) was used to measure volume changes in the proximal stomach. A polyethylene bag (1000 ml maximum) was tied to the end of a 16 French multilumen catheter. This catheter was connected to a barostat device [20]. Pressure (mmHg) and volume (ml) were constantly monitored and recorded on a computer equipped with dedicated software that corrects volume for air compressibility and temperature (Polygram for Windows, SVS module; Synectics Medical).

Study days

Each subject participated in three study periods, separated by at least 7 days. Subjects reported to the research unit the evening before drug administration. In the morning of the study day, after an overnight fast of at least 10 h, two indwelling intravenous cannulas were inserted in hand and antecubital veins of one arm to administer RWJ-68023/placebo and motilin. A third cannula was inserted in the contralateral arm for blood sampling. The barostat catheter was then positioned through the mouth in the fundus of the stomach and the correct position was checked by fluoroscopy. The subjects were studied in a semirecumbent position, with the lower extremities just above abdominal level. The following procedures were performed (a scheme of the protocol is presented in Figure 1).

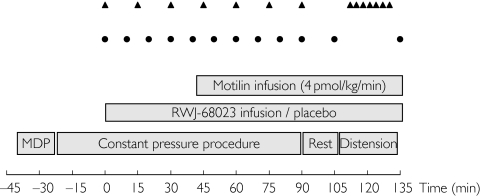

Figure 1.

Protocol design. Visual analogue scales (triangles) and blood sampling for motilin and RWJ-68023 (circles)

Minimal distending pressure procedure

The minimal distending pressure (MDP) is the pressure level needed to overcome intra-abdominal pressure [21]. This was determined by increasing intrabag pressure in 1-mmHg steps every 2 min until a bag volume of 30 ml or more was reached.

Constant pressure procedure

After determination of the MDP, a constant pressure procedure was started, at a pressure of 3 mmHg above MDP. During this constant pressure procedure, RWJ-68023/placebo infusion was started at t = 0 min after a 20-min baseline recording. RWJ-68023 infusion continued for 135 min. Motilin infusion was started 45 min after the start of the RWJ-68023/placebo infusion. The constant pressure procedure continued until 45 min after the start of the motilin infusion. After completion of this procedure, a resting period of 15 min was scheduled.

Isobaric distension procedure

After the constant pressure procedure, a stepwise pressure distension procedure was performed; isobaric distensions were performed in 1-mmHg steps, every 90 s from 0 mmHg to a maximum of 14 mmHg. The procedure was stopped if a bag volume of 800 ml was reached or if the subject could not tolerate further distension.

Perception of abdominal feelings such as fullness, nausea, upper abdominal pain and tension, hunger and wish to eat was scored on a 100 mm visual analogue scales (VAS) [22]. These symptoms were scored predose (t = 0 min), at every 15 min during the constant pressure procedure and at every second pressure level during the distension procedure.

After cessation of the infusion (t = 135 min) the barostat catheter was withdrawn and the subjects were offered lunch. The subjects were hospitalized at the research unit 24 h after the infusion of RWJ-68023, for safety purposes.

Treatments and infusions

The infusion schedules were calculated, using human pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters obtained from the first PK study, to obtain steady-state concentrations rapidly at the levels of receptor blockade.

On separate occasions, subjects received one of the following i.v. infusions (135 min) in randomized order:

RWJ-68023 1.02 mg kg-1 over 30 min, followed by 2.6 mg kg-1 over 105 min (total dose =3.62 mg kg-1) (high dose);

RWJ-68023 0.1 mg kg-1 over 30 min, followed by 0.275 mg kg-1 over 105 min (total dose =0.375 mg kg-1) (low dose);

Placebo.

On each occasion the subjects received an i.v. infusion of motilin at a dose of 4 pmol kg−1 min−1 for 90 min, starting 45 min after the RWJ-68023/placebo infusion. The motilin used in this study was synthetic human motilin manufactured by the American Pep-tide Co. Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and prepared for human use by Clinalfa AG (Läufelfingen, Switzerland).

Infusions were performed with calibrated volumetric infusion pumps. The high- and low-dose RWJ-68023 were infused with a constant infusion rate of 193.8 ml h−1 and 19.0 ml h−1 over the first 30 min followed by a constant infusion rate of 141.0 ml h−1 and 14.9 ml h−1 over the last 105 min, respectively. Due to the fact that the low-dose RWJ-68023 could not be diluted in the same volume as the high dose, a double-dummy approach was applied. Hence, during the infusion of the high-dose RWJ-68023, placebo was infused at a rate of the low-dose treatment, and during the infusion of the low-dose RWJ-68023, placebo was infused at the rate of the high-dose treatment.

Motilin was infused with a constant infusion rate of 24.0 ml h−1.

Sample handling and motilin assay

Blood samples for motilin and RWJ-68023 concentration analysis were drawn at t = −1, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 90, 105 and 135 min, and at 24 h (RWJ-68023 concentration only). Blood samples were collected in 3-ml glass clotting tubes (motilin) and in 5-ml Na/Heparin (RWJ-68023). Blood samples were kept on ice and centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C (2000 × g). The serum and plasma samples were stored at −40 °C until analysis. The assay for motilin was done with a sensitive (limit of detection 15.6 pmol l−1) and specific radioimmunoassay (TNO, Zeist, the Netherlands) and the assay for RWJ-68023 was done with liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry with a limit of detection 0.70 pmol ml−1 (Medeval, Manchester, UK).

Safety

Evaluations were performed during the study to measure the safety and tolerability of RWJ-6823. Safety evaluations consisted of vital signs (systolic, diastolic blood pressure and pulse rate), body temperature, 12-lead ECG, continuous ECG recording around dosing, clinical laboratory tests (blood chemistry, haematology and urinalysis), standard neurological examination, physical examination and adverse events (AEs).

Data analysis

Pharmacokinetic analysis

Baseline serum motilin was calculated as the average of the motilin levels from t = 0–40 min. The PK for exogenous motilin were evaluated as reported previously [3, 23]. The RWJ-68023 PK parameters were the maximal concentration (Cmax) of RWJ-68023 plasma levels, and the area under the concentration curve from t = 0–135 min (AUC0−135).

To investigate possible effects of the different polymorphisms on RWJ-68023 PK parameters, log-transformed AUC and Cmax of the high-dose RWJ-68023 were compared between the different genotype expression groups. Differences in motilin pharmacokinetics between the different genotype expression groups were assessed by comparing the average log transformed AUC and Cmax. Results from the distinct treatments were pooled, because average motilin concentration profiles indicated complete superposition of the three treatments.

Proximal gastric volume during constant pressure procedure

Proximal gastric volume was measured continuously and average values over 5-min periods were analysed. Baseline gastric volume was calculated as the average volume during the 15-min period (t = −10, −5 and 0 min) preceding the start of the RWJ-68023/placebo infusion. During the constant pressure procedure, RWJ-68023/placebo was infused alone for 45 min, followed by a period of 45 min with simultaneous motilin infusion (Figure 1). Measures were calculated reflecting these different periods; the effect of RWJ-68023 alone on proximal gastric volume was calculated from t = 0–45 min, and its effect together with the motilin challenge was calculated from t = 45–90 min. For RWJ-68023 alone, absolute changes in gastric volume from baseline were calculated. For RWJ-68023 together with motilin infusion, absolute changes were calculated both from baseline and from the last 15 min of the period of RWJ-68023 infusion without simultaneous motilin (t = 35, 40 and 45 min).

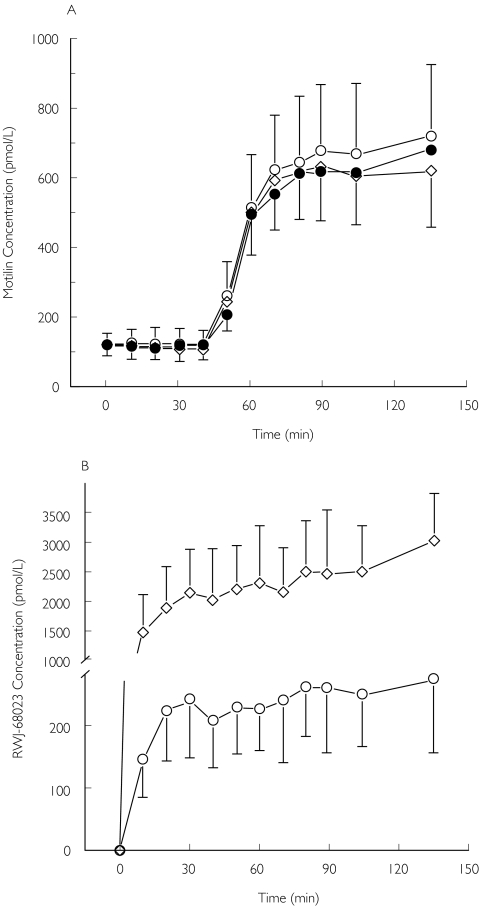

Proximal gastric volume during distension procedure

Proximal gastric volume was measured continuously and average values over the last 30 s of each pressure level were analysed. Volumes at the highest pressure level and at the highest pressure level that was tolerated by everyone were analysed. In addition, compliance of the proximal stomach was quantified from the distension data, by smoothing the distension volume/pressure curve using a sigmoid Emax model (Figure 4). The maximum slope was used as a measure of compliance. Sigmoid Emax modelling was performed using SAS PROC NLIN (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Figure 4.

Proximal gastric volume (ml) during isobaric distensions during infusion of placebo (•), the low- (○) and high-dose RWJ-68023 (▵) (mean ± SD, N = 16). The gastric volume during high-dose RWJ-68023 was significantly (*P = 0.014) greater at the highest pressure level than placebo

Note that during this procedure, the effect of simultaneous RWJ-68023 and motilin administration on gastric volume and compliance was measured.

Abdominal sensation

Perception scores on 100 mm VAS were calculated in mm.

During the constant pressure procedure, baseline was characterized as the value at t = 0 min. The effect of RWJ-68023 on VAS response was calculated as the average of the values at t = 15, 30 and 45 min. The simultaneous effect of RWJ-68023 and motilin was calculated as the average of the values at t = 60, 75 and 90 min. The effect of RWJ-68023 alone and simultaneous with motilin was characterized by both absolute values and the differences from baseline.

During the distension procedure, baseline was characterized as the first value of this procedure. VAS response was calculated as the average of the values at every second pressure increment from 0 mmHg until the maximum pressure and until the highest pressure level that was tolerated by everyone. Treatment effect was characterized by both absolute values and differences from baseline. Note that during the distension procedure, the simultaneous effect of RWJ-68023 and motilin was measured.

Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Differences between treatments were analysed using analysis of variance, reported with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). All analyses were performed using SAS version 8.1 (SAS Institute). P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Safety

There were no serious AEs. The most common AEs were GI complaints, which included nausea, abdominal pain and discomfort. These AEs were considered to be treatment-related and were more frequent for subjects receiving the low (57% of the patients) and high dose of RWJ-68023 (55% of the patients) than placebo (26% of the patients). No clinically relevant findings were observed for all other safety evaluations. Five subjects dropped out due to difficulties with swallowing the barostat catheter and one subject was replaced due to deviations from the infusion procedure. A total of 18 subjects completed the study. For two subjects, the distension data of a single study day are not available due to vomiting (one subject on placebo and one on high-dose RWJ-68023). Another subject was excluded entirely from the distension analysis, because of missing distension data during 2 study days, due to technical difficulties.

Pharmacokinetics

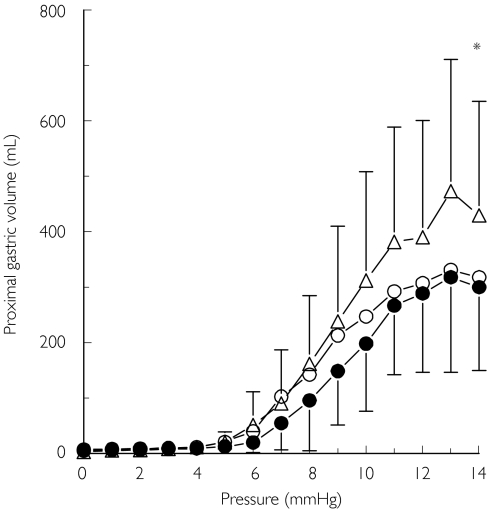

Motilin pharmacokinetics were similar to those observed in previous studies [3, 23] (Figure 2). Motilin and RWJ-68023 PK parameters are presented in Table 1. No effect of the RWJ-68023 infusion on motilin pharmacokinetics could be detected. The results of the genotype assessment indicated several subjects being poor metabolizers through the CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6 and NAT2 metabolic pathway. However, for RWJ-68023 and motilin, none of the polymorphisms was associated with differences in Cmax or AUC from the wild type with P > 0.1.

Figure 2.

(A) Serum motilin concentrations (pmol l−1) during infusion of placebo (•), the low- (○) and the high-dose RWJ-68023 (◊) (mean ± SD; N = 18). (B) Plasma RWJ-68023 concentrations (ng ml−1) during infusion of the low- (○) and the high-dose RWJ-68023 (◊) (mean ± SD; N = 18)

Table 1.

Serum motilin and plasma RWJ-68023 pharmacokinetic parameters during infusion of placebo, the low- and high-dose RWJ-68023 and overall of the three treatments (mean ± SD)

| Placebo N = 16 | RWJ-68023 low N = 17 | RWJ-68023 high N = 17 | Overall N = 50 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motilin pharmacokinetic parameters | ||||

| Baseline concentration (pmol l−1) | 118.1 ± 32.8 | 123.2 ± 38.8 | 117.2 ± 33.6 | 119.6 ± 34.6 |

| Clearance (ml min−1) | 560 ± 136 | 589 ± 277 | 596 ± 133 | 582 ± 192 |

| Half life (min) | 12.9 ± 5.7 | 11.2 ± 4.7 | 10.5 ± 6.4 | 11.5 ± 5.6 |

| RWJ-68023 pharmacokinetic parameters | ||||

| Cmax (µmol ml−1) | – | 341.4 ± 91.9 | 3254.2 ± 898.2 | – |

| AUC (h × µmol ml−1) | – | 506.0 ± 142.6 | 5030.5 ± 1431.1 | – |

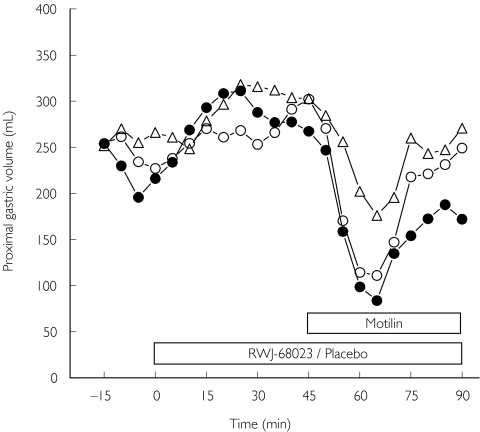

Gastric volume during constant pressure procedure

MDPs and baseline proximal gastric volumes were similar for each treatment (Table 2). Before the infusion of motilin, no effect of either the high- or low-dose RWJ-68023 was observed on proximal gastric volume, when compared with placebo. Motilin reduced gastric volume from baseline during infusion of placebo by 27%, a similar magnitude as reported previously [14, 24]. The high-dose RWJ-68023 reduced this contractile effect of motilin on the proximal stomach by 60% and the low dose by 10% (Figure 3), although these differences were not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Proximal gastric parameters during placebo, the low- and high-dose RWJ-68023 infusion (with/without concomitant motilin infusion), during the minimal distending pressure (MDP), constant pressure (MDP +3 mmHg) (N = 18/17, 17/17, 18/17) and distension procedure (N = 16, 16, 15) (mean ± SD)

| Placebo | RWJ-68023 low dose | RWJ-68023 high dose | Difference RWJ-68023 high–placebo (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDP (mmHg) | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 7.4 ± 1.2 | 7.2 ± 1.1 | |

| Constant pressure procedure before motilin infusion | ||||

| Baseline gastric volume (ml) | 214 ± 85 | 241 ± 72 | 264 ± 109 | |

| Average volume from 0 to 45 min (ml) | 281 ± 109 | 267 ± 81 | 293 ± 124 | |

| Average volume change from baseline (ml) | 67 ± 66 | 26 ± 70 | 29 ± 63 | − 37 (−85, 10) |

| Constant pressure procedure during motilin infusion | ||||

| Average volume from 45 to 90 min | 157 ± 74 | 193 ± 76 | 237 ± 113 | |

| Average volume change from baseline (ml) | −52 ± 61 | −48 ± 82 | −21 ± 81 | 30 (−18, 79) |

| Average volume change from period 35–45 min (RWJ-68023/placebo infusion without motilin infusion) | −111 ± 94 | −94 ± 87 | −60 ± 83 | 52 (−16, 119) |

| Distension procedure (with concomitant motilin infusion) | ||||

| Volume at maximum pressure (14 mmHg) (ml) | 334 ± 174 | 340 ± 178 | 483 ± 222 | 145 (32, 257)* |

| Volume at pressure everyone tolerated (ml) | 267 ± 125 | 292 ± 151 | 382 ± 207 | 112 (25, 199)* |

| Compliance (ml mmHg−1) | 80 ± 42 | 132 ± 148 | 123 ± 77 | 59 (−15, 134) |

Differences between the high-dose RWJ-68023 and placebo are presented with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

P < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Proximal gastric volume (ml) during the constant pressure procedure (minimal distending pressure +3 mmHg) during infusion of placebo (•), the low- (○) and high-dose RWJ-68023 (□) (mean ± SD; N = 18)

Gastric volume during distension procedure

During each treatment, distension of the stomach with increasing pressure levels resulted in increasing gastric volumes. However, during the simultaneous infusion of the high-dose RWJ-68023 and motilin, the stomach was able to distend more than during the simultaneous infusion of either the low-dose RWJ-68023 or placebo and motilin (Figure 4) (Table 2). This was reflected by a statistically significant increase in gastric volume at maximum pressure during infusion of the high-dose RWJ-68023 in comparison with placebo (P = 0.014) and with the low-dose RWJ-68023 (P = 0.016). It was also reflected by a significant increase in gastric volume at the highest pressure level that was tolerated by every-one during infusion of the high-dose RWJ-68023 in comparison with placebo (P = 0.013). This motilin-antagonizing effect of RWJ-68023 was not observed during infusion of the low-dose RWJ-68023, compared with placebo.

Abdominal sensation

During the constant pressure procedure, during the infusion of the low-dose RWJ-68023 before the start of the motilin infusion, nauseous feelings, scored by VAS, were significantly increased compared with placebo (P = 0.03). However, no statistically significant difference was detected between the high-dose RWJ-68023 and placebo. For all other abdominal sensations scored, no statistically significant differences were found between treatments.

During the distension procedure, increasing pressure levels only resulted in increased feelings of abdominal tension, but no differences between treatments were observed for this or other abdominal feelings.

Discussion

This study investigated the motilin-antagonizing effects of the nonpeptide motilin receptor antagonist RWJ-68023 on basal and motilin-stimulated proximal gastric volume in healthy volunteers, in order to obtain more insight into the postulated therapeutic value of motilin antagonism in the treatment of functional motility disorders. The potential therapeutic value of a motilin antagonist in FD was suggested as motilin induces impaired postprandial relaxation in healthy volunteers similar to that observed in patients with FD, and induces nauseous feelings postprandially in healthy volunteers [3]. Thus, it was suggested that motilin might play a role in the pathogenesis of FD. The potentially motilin-antagonistic effects of RWJ-68023 were, however, studied in fasted state and not postprandially, as many regulatory mechanisms other than motilin are involved in the postprandial relaxation of the proximal stomach and may have interfered with the investigation of the pure motilin-antagonizing properties of RWJ-68023.

The most common AEs of RWJ-68023 were mild and of GI origin, including nausea, abdominal pain and discomfort. Measuring proximal gastric volume by a barostat is an invasive method and may induce unpleasant GI sensations. However, the GI AEs cannot be fully ascribed to the invasive methodology, as AEs were more frequent for subjects receiving RWJ-68023. Similar to other studies in our institute using the presently employed motilin dose, motilin was well tolerated by fasted healthy subjects [14, 25].

RWJ-68023 alone, in either the high or low dose, did not affect proximal gastric volume. This may be an indication of the fact that the influence of endogenous motilin on gastric tone is low and that motilin may not be an important determinant of the basal tonic condition of the stomach, but it may also be a reflection of the low potency of the motilin antagonist.

Motilin reduced proximal gastric volume with a similar magnitude as reported in previous studies [14, 24], although the presently assessed reduction was expressed relative to baseline and no direct comparison with a placebo group could be made. The volume-reducing effect of motilin on the stomach seemed to diminish in time. At present no clear explanation for this observation is available, but motilin-induced tachyphylaxis of calcium mobilization has been observed in TE 671 cells in vitro upon multiple exposure to motilin [26]. In addition, in an animal study, tachyphylaxis has been observed with the motilin agonist ABT-229 [25]. Both the motilin and motilin-antagonizing effect of RWJ-68023 are variable. Part of this variability may be explained by the refractory period of the GI tract to motilin. A refractory period exists after a phase 3 (of antral origin) of the migrating motor complex, in which the GI tract is not responsive to motilin [27]. The motilin infusion was unrelated to the endogenous motilin peak and thus to the phase of the migrating motor complex. Thus, motilin may have been infused during a refractory period. However, no correlation was found between basal motilin levels and proximal gastric response to motilin and RWJ-68023.

In this study, motilin has a half-life of approximately 11 min, while in previous reports motilin was found to have a half-life in the order of 5 min [28, 29]. It must be noted that in the previous reports another motilin analogue was used (amino acid methionine was substituted with norleucine), while in the present study synthetic human motilin was employed.

The current data do not provide information about the mechanism by which motilin and RWJ-68023 affect gastric motility. However, motilin receptors have been shown to be present in gastric wall nerves and smooth muscle cells [30–32] and hence it is likely that the motilin effect is mediated through a direct interaction with these receptors [30, 33, 34]. Being a potent inhibitor of motilin binding to both endogenous and cloned human motilin receptors [15], the motilin-antagonizing effect of RWJ-68023 is likely to be mediated through direct interaction with the motilin receptor.

RWJ-68023 tended to inhibit the motilin-induced contraction of the proximal stomach, but variability was large and statistical significance was reached only during the distension procedure. The disparity between the results of the constant pressure and distension procedure may relate to the fact that RWJ-68023 serum levels increased until the end of infusion (Figure 2b), and thus the maximal effect may not have been reached during the constant pressure procedure. On basis of in vitro data, however, the concentrations observed after the high-dose infusion should theoretically have yielded a receptor blockade of at least 90%. The attained RWJ-68023 concentrations not reaching the expected receptor blockade, but only receptor blockade of 10–60%, cannot be explained from the present data, but it is possible that due to binding of RWJ-68023 to plasma proteins, lower active RWJ-68023 concentrations were reached than anticipated on the basis of preclinical data. On the other hand, it is also possible that RWJ-68023 exerts its effect locally in the gut and did not reach the gastric tissue properly after i.v. administration. In that case, oral administration of RWJ-68023 might be a better approach to reach the target tissue. Although in vitro binding studies have shown a similar binding of RWJ-68023 to human and animal receptors, RWJ-68023 might be a less potent motilin antagonist in humans due to differences in postreceptor events.

The changes in proximal gastric volumes did not coincide with changes in most upper abdominal feelings, but nauseous feelings were significantly increased during the low-dose RWJ-68023 infusion without concomitant motilin infusion. This finding may be of little clinical relevance as no statistically significant difference was detected between the high-dose RWJ-68023 and placebo. It may be a chance statistically significant result, as there was one analysis with P < 0.05 out of 24 tests, consistent with what was expected by chance if there were no real treatment differences.

In conclusion, intravenous RWJ-68023 infusion was safe and well tolerated in healthy male volunteers. The RWJ-68023 doses used in this study were selected to accomplish plasma concentrations that would block the motilin effect entirely. However, the antagonizing effect of RWJ-68023 on the motilin effect on the proximal stomach was partial and only present when the tonic condition of the proximal stomach was modulated by exogenous motilin. Higher doses of RWJ may produce more inhibition, but in view of the theoretical receptor inhibition accomplished this is unlikely.

RWJ-68023 was developed as a potential future treatment for intestinal motility disorders, but its value as useful therapeutic intervention in these disorders was not strongly supported by the data of the present study.

In addition, our data demonstrate that in vivo receptor antagonism at tissue level cannot always be predicted reliably on the basis of in vitro profiles and that model studies like these are essential to confirm or refute results from preclinical studies before the start of larger and more costly Phase II–III trials or for the design of orally available follow-ups.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development (L.L.C., Raritan, NJ, USA).

References

- 1.Polak JM, Pearse AG, Heath CM. Complete identification of endocrine cells in the gastrointestinal tract using semithin-thin sections to identify motilin cells in human and animal intestine. Gut. 1975;16:225–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.16.3.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peeters TL, Vantrappen G, Janssens J. Fasting plasma motilin levels are related to the interdigestive motility complex. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:716–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamerling IMC, Van Haarst AD, Burggraaf J, et al. Exogenous motilin affects postprandial proximal gastric motor function and visceral sensation. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1732–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1016522625201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malagelada JR. Gastrointestinal motor disturbances in functional dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;182(Suppl):29–32. doi: 10.3109/00365529109109534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tack J, Piessevaux H, Coulie B, Caenepeel P, Janssens J. Role of impaired gastric accommodation to a meal in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1346–52. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Paternico A, et al. Risk indicators of delayed gastric emptying of solids in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1036–42. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8612991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorard DA, Farthing MJ. Intestinal motor function in irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis. 1994;12:72–84. doi: 10.1159/000171440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kellow JE, Phillips SF. Altered small bowel motility in irritable bowel syndrome is correlated with symptoms. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1885–93. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90620-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukudo S, Suzuki J. Colonic motility, autonomic function, and gastrointestinal hormones under psychological stress on irritable bowel syndrome. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1987;151:373–85. doi: 10.1620/tjem.151.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sjölund K, Ekman R. Are gut peptides responsible for the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)? Scand J Gastroenterol. 1987;130(Suppl):15–20. doi: 10.3109/00365528709090995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simren M, Abrahamsson H, Bjornsson ES. An exaggerated sensory component of the gastrocolonic response in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2001;48:20–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tack J, Peeters T. What comes after macrolides and other motilin stimulants? Gut. 2001;49:317–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talley NJ. Review article: functional dyspepsia – should treatment be targeted on disturbed physiology? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamerling IMC, Van Haarst AD, Burggraaf J, et al. Motilin effects on the proximal stomach in patients with functional dyspepsia and healthy volunteers. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G776–81. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00456.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beavers MP, Gunnet JW, Hageman W, et al. Discovery of the first non-peptide antagonist of the motilin receptor. Drug Des Discov. 2001;17:243–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Depoortere I, Macielag MJ, Galdes A, Peeters TL. Antagonistic properties of [Phe(3),Leu(13)] porcine motilin. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;286:241–7. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poitras P, Miller P, St Gagnon D, St-Pierre S. Motilin synthetic analogues and motilin receptor antagonists. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;205:449–54. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwai T, Nakamura H, Takanashi H, et al. Hypotensive mechanism of [Leu13]motilin in dogs in vivo and in vitro. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1998;76:1103–9. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-76-12-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takanashi H, Yogo K, Ozaki K, et al. GM-109: a novel, selective motilin receptor antagonist in the smooth muscle of the rabbit small intestine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:624–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitehead WE, Delvaux M. Standardization of barostat procedures for testing smooth muscle tone and sensory thresholds in the gastrointestinal tract. The Working Team of Glaxo-Wellcome Research, UK. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:223–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1018885028501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Gastric tone measured by an electronic barostat in health and postsurgical gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:934–43. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90967-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stubbs RJ, Hughes DA, Johnstone AM, et al. The use of visual analogue scales to assess motivation to eat in human subjects: a review of their reliability and validity with an evaluation of new hand-held computerized systems for temporal tracking of appetite ratings. Br J Nutr. 2000;84:405–15. doi: 10.1017/s0007114500001719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamerling IMC, Van Haarst AD, Burggraaf J, et al. Dose-related effects of motilin on proximal gastrointestinal motility. Alimentary Pharmacol Therapeutics. 2002;16:129–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coulie B, Vandaele P, Tack J, Janssens J. Motilin increases tone of the gastric fundus in man. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:A1140. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thielemans L, Van Depoortere IA, Bender E, Peeters TL. Demonstration of a functional motilin receptor in TE671 cells from human cerebellum. Brain Res. 2001;895:119–28. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Depoortere I, Verlinden M, Thijs T, Van Assche G. The motilide ABT-299 selectively downregulates motilin receptors in different tissues. Evidence for motilin receptor subtyes. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:G4610. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luiking YC, van Akkermans LM, d Peeters TL, van Berge H. Differential effects of motilin on interdigestive motility of the human gastric antrum, pylorus, small intestine and gallbladder. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2003;15:103–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2003.00395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitznegg P, Bloom SR, Domschke W, Domschke S, Wuensch E, Demling L. Pharmacokinetics of motilin in man. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:413–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Modlin IM, Mitznegg P, Bloom SR. Motilin release in the pig. Gut. 1978;19:399–402. doi: 10.1136/gut.19.5.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ludtke FE, Muller H, Golenhofen K. Direct effects of motilin on isolated smooth muscle from various regions of the human stomach. Pflugers Arch. 1989;414:558–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00580991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peeters TL, Bormans V, Vantrappen G. Comparison of motilin binding to crude homogenates of human and canine gastrointestinal smooth muscle tissue. Regul Pept. 1988;23:171–82. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(88)90025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller P, Roy A, St Pierre S, Dagenais M, Lapointe R, Poitras P. Motilin receptors in the human antrum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;278:G18–G23. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.278.1.G18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strunz U, Domschke W, Mitznegg P, et al. Analysis of the motor effects of 13-norleucine motilin on the rabbit, guinea pig, rat, and human alimentary tract in vitro. Gastroenterology. 1975;68:1485–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strunz U, Domschke W, Domschke S, et al. Gastroduodenal motor response to natural motilin and synthetic position 13-substituted motilin analogues: a comparative in vitro study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1976;11:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]