Abstract

Aims

The present study addressed the ability of levofloxacin to penetrate into subcutaneous adipose tissues in patients with soft tissue infection.

Methods

Tissue concentrations of levofloxacin in inflamed and healthy subcutaneous adipose tissue were measured in six patients by microdialysis after administration of a single intravenous dose of 500 mg. Levofloxacin was assayed by high-performance liquid chromatography.

Results

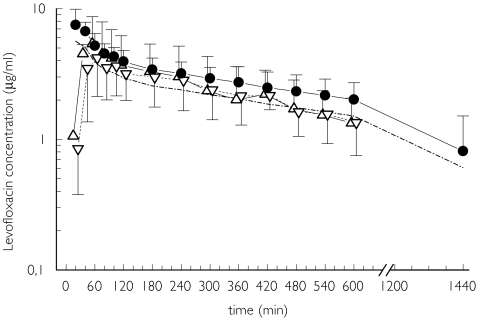

The mean concentration vs time profile of free levofloxacin in plasma was identical to that in inflamed and healthy tissues. The ratios of the mean area under the free levofloxacin concentration vs time curve from 0 to 10 h (AUC(0,10 h)) in tissue to that in plasma were 1.2 ± 1.0 for inflamed and 1.1 ± 0.6 for healthy subcutaneous adipose tissue (mean ± SD). The mean difference in the ratio of the AUCtissue : AUCplasma for inflamed and healthy tissue was 0.09 (95% confidence interval −0.58, 0.759, P > 0.05). Interindividual variability in tissue penetration was high, as indicated by a coefficient of variation of approximately 82% for AUCtissue : AUCplasma ratios.

Conclusions

The penetration of levofloxacin into tissue appears to be unaffected by local inflammation. Our plasma and tissue data suggest that an intravenous dose of 500 mg levofloxacin provides effective antibacterial concentrations at the target site. However, in treatment resistant patients, tissue concentrations may be sub-therapeutic.

Keywords: fluoroquinolones, levofloxacin, microdialysis, soft tissue infections, target site pharmacokinetics, tissue penetration

Introduction

Infections are usually treated by empirical antibiotic regimens and drug concentrations in plasma are considered appropriate to guide dosage of antimicrobial therapy. However, recent studies support the view that subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics might be achieved in soft tissues, despite adequate plasma concentrations [1–3]. Tissue penetration of antimicrobial agents has been reported to be substantially affected in inflammatory states by changes in blood flow, loss of capillary integrity, oedema and altered protein content in the interstitial space fluid in infected tissues [4]. Thus, it has been concluded that systemic or local inflammation is linked to decreased concentrations of antibiotics at the target site as shown for β-lactams, moxifloxacin, imipenem and fosfomycin in patients with sepsis or diabetic patients presenting with soft tissue infections (STIs) [2, 5–8]. Subinhibitory target site concentrations may contribute to clinical cases where antimicrobial agents fail to eradicate the relevant pathogen, despite documented susceptibility in vitro. In addition, ineffective concentrations at the target site have also been shown to act as a trigger for the development of resistance [9]. These findings raise the question of whether plasma concentrations correspond to target site concentrations of antimicrobial agents in the clinical setting.

Thus, the present study tested the ability of levofloxacin to penetrate into inflamed and healthy subcutaneous adipose tissues.

Methods

The study was carried out at the Department of Clinical Pharmacology, University of Vienna. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Vienna General Hospital and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) in the revised version of 1996 (Somerset West), the Guidelines of the International Conference of Harmonization, the Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Austrian drug law (Arzneimittelgesetz). Patients provided written informed consent prior to participation. Eight patients, six males and two females, with soft tissue infections requiring intravenous antibiotic therapy were included. Their mean age was 56 ± 22 years (mean ± SD), mean body weight was 79.7 ± 9.0 kg and mean serum creatinine concentration was 1.12 ± 0.22 mg dl−1 (Table 1). Three patients (two diabetic and one non-diabetic) had documented peripheral stage IV arterial occlusive disease of the lower limbs [10]. Patients attended a screening visit comprising a medical history, clinical examination, routine blood and urine tests and an ECG. In female subjects a pregnancy test was performed. Patients were excluded if they had had treatment with other fluoroquinolones within the 5 days prior to the start of the study, prolonged QTc at ECG (> 450 ms in males and > 470 in females), a history of epilepsy, impaired renal function (serum creatinine >1.5 mg dl−1, undergoing haemodialysis or haemofiltration), a positive HIV test, were pregnant or lactating, or were allergic or hypersensitive to levofloxacin.

Table 1.

Demographic data

| Patient | Sex | Age (years) | Weight (kg) | Creatinine plasma (mg dl−1) | Urea (mg dl−1) | Diabetes | Inflammation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 23 | 69 | 0.81 | 12.8 | No | Acute |

| 2 | M | 41 | 72 | 1.11 | 15.8 | No | Acute |

| 3 | M | 50 | 92 | 1.03 | 11.2 | Yes | Chronic |

| 4 | F | 42 | 92 | 0.86 | 9.0 | No | Acute |

| 5 | M | 89 | 75 | 1.34 | 30.7 | Yes | PAOD (stage IV), chronic |

| 6 | M | 78 | 73 | 1.48 | 25.3 | No | PAOD (stage IV), chronic |

| 7 | M | 68 | 85 | 1.18 | 18.4 | Yes | PAOD (stage IV), chronic |

In one patient (patient 5) no microdialysate samples could be obtained due to the malfunction of the microdialysis probes and only plasma samples were analyzed. PAOD; Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (stage IV) according to Fontaine classification.

Levofloxacin administration

Levofloxacin (Tavanic, Aventis, Frankfurt/Main, Germany) was administered as a single intravenous dose of 500 mg over 30 min using an automatic infusion apparatus (Infusionspumpe IP 85–2, Döring Medizintechnik, Leverkusen, Germany).

Sample collection in vivo microdialysis

The technique used has been described in detail previously [11–13]. Microdialysis is based on sampling of analytes from the extracellular space by means of a semipermeable membrane at the tip of a probe, which is implanted into the tissue. A total of two microdialysis probes (CMA 10, molecular weight cut-off 20 kDa; Microdialysis, Stockholm, Sweden) were inserted into soft tissues. In patients with diabetic soft tissue infection, one probe was inserted very close to the margins of the ulcers. In patients with acute soft tissue infections without ischaemic or necrotic regions, the probes were positioned in inflammatory, well-perfused, hyperaemic zones. The reference probe was inserted into healthy subcutaneous adipose tissue in the contralateral thigh. This was done as follows: after cleaning and disinfection, the skin was punctured by a 20 gauge IV plastic cannula. The steel mandrin was removed, and the dialysis probe was inserted into the plastic cannula. The microdialysis system was attached and perfused with Ringer's solution at a flow rate of 1.5 µl min−1 using a microinfusion-pump (CMA 100, Microdialysis, Stockholm, Sweden).

Principle of microdialysis

Drugs present in the extracellular fluid at a concentration (Ctissue) can enter the dialysate in the probe by diffusion, resulting in a concentration (Cdialysate) in the perfusion medium. For most analytes, equilibrium between extracellular tissue fluid and the perfusion medium is incomplete (Ctissue > Cdialysate). The factor by which the two concentrations are interrelated is termed relative recovery, which was determined by performing an in vivo probe calibration using retrodialysis after a 30 min baseline sampling period. The principle of retrodialysis relies on the assumption that the diffusion process is quantitatively equal in both directions through the semipermeable membrane. Levofloxacin was added to the perfusion medium at a concentration of 1 µg ml−1 and its rate of disappearance through the membrane was taken as the in vivo recovery [8]. Thus,

Extracellular concentrations were calculated according to the following equation [8]:

After in vivo calibration of the probes, levofloxacin was administered to the patients. The probes were removed immediately after the end of the dialysate sampling period. Sampling of dialysate and venous blood was performed at 20 min intervals for the first 2 h and at 60 min intervals up to 10 h after start of infusion. Blood samples were kept on ice for a maximum of 60 min and were centrifuged at 4 °C and 2000 g for 5 min. Plasma and dialysate samples were snap frozen overnight at −20 °C and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Measurement of levofloxacin

Levofloxacin was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described by Neckel et al.[14]. Separation was performed on a C18 Hypersil ODS column (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 5 µm; Hypersil, Runcorn, UK) connected to a C18 precolumn (ODS, 4 mm × 2.0 mm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of ortho-phosphoric acid, tetrabutyammonium hydroxide and acetonitrile. Levofloxacin was measured by fluorescence excitation and emission wavelengths of 310 nm and 467 nm, respectively. The detection limit was 0.016 µg ml−1 in microdialysates and 0.02 µg ml−1 in plasma. The accuracy ranged from 78% to 107% with a precision less than 5% (coefficient of variation) [14].

Pharmacokinetic (PK) calculations and statistical comparison

Free levofloxacin concentrations were calculated from total plasma concentrations using a literature value of 25% bound to plasma [15, 16]. Pharmacokinetic analysis was performed using commercially available software (Kinetica 2000, InnaPhase Corporation Sarl, Paris, France) and parameters were calculated using noncompartmental methods. The following main PK parameters were determined: area under the concentration-time curve (AUC(0,10 h)), maximum concentration (Cmax), time to maximum concentration (tmax), elimination half-life (t½,z), clearance (CL) and apparent volume of distribution (Vz).

The Wilcoxon test was used to compare pharmacokinetic parameters. All data are displayed as means ± SD. A two sided P value < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Eight patients were enrolled in the study. In one (patient 5) no microdialysate samples could be obtained due to the malfunction of the probes and only plasma samples were analyzed. Another patient (not listed in Table 1) decided to withdraw from the study during the intravenous infusion of levofloxacin. The levofloxacin concentration-time profiles for plasma, inflamed and healthy subcutaneous adipose tissue are displayed in Figure 1, and the pharmacokinetic parameters are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Concentration vs time profiles for total (•) and free levofloxacin (–·–·–) in plasma (n = 7), and inflamed (▵) and healthy tissue (▿) (n = 6). Data are presented as means ± SD

Table 2.

Presents the pharmacokinetics of levofloxacin for plasma (n = 7), inflamed and healthy subcutaneous adipose tissue (n = 6). Data are shown as mean ± SD and (95% confidence intervals)

| Compartment | AUC(0,10 h) tissue : AUC(0,10 h) free plasma ratio | AUC(0,10 h) (mg l−1 h) | AUC(0,24 h) (mg l−1 h) plasma | Cmax (mg l−1) | tmax (h) | t½β (h) | CL (l h−1 kg−1) | Vz (l kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma, total | — | 32.3 ± 7.3 | 52.1 ± 17.3 | 8.37 ± 1.93 | 0.52 ± 0.26 | 10.0 ± 6.3 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 1.35 ± 0.30 |

| (n = 7) | (25.5–39.1) | (36.0–68.1) | (6.6–10.2) | (0.28–0.77) | (4.2–16.0) | (0.07–0.16) | (1.08–1.63) | |

| Tissue Inflamed | 1.15 ± 0.95 | 25.5 ± 16.8 | 5.45 ± 3.74 | 1.06 ± 0.14 | ||||

| (n = 6) | (0.15–2.15) | (7.9–43.1) | n.d. | (1.53–9.37) | (0.91–1.20) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| Tissue Healthy | 1.06 ± 0.61 | 23.5 ± 10.0 | 4.42 ± 2.09 | 1.39 ± 1.29 | ||||

| (n = 6) | (0.43–1.70) | (13.0–33.9) | n.d. | (2.22–6.61) | (0.04–2.74) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

n.d: not determined.

The mean value of Cmax for total levofloxacin in plasma was 8.37 ± 1.93 µg ml−1 (mean ± SD), the mean AUC(0,10 h) value for total levofloxacin was 32.3 ± 7.3 mg l−1 h, and the mean elimination half-life at the terminal phase was 10.0 ± 6.3 h. The mean clearance of total levofloxacin in plasma was 0.115 ± 0.053 l h−1 kg−1 (95% CI 0.066, 0.164), and the mean apparent volume of distribution was 1.35 ± 0.30 l kg−1 (95% CI 1.08, 1.63; see Table 2).

The mean in vivo recovery of levofloxacin was approximately 35% in both inflamed and healthy adipose tissue. Pharmacokinetic parameters derived from microdialysate samples are presented in Table 2. The time to peak concentration (tmax) was 1.06 ± 0.14 h in inflamed soft tissue and 1.39 ± 1.29 h in healthy tissue (mean difference −0.33, 95% CI −2.53, 4.58, P = 0.72). The mean ratio of AUC(0,10 h)tissue : AUC(0,10 h)free plasma was 1.2 ± 1.0 for inflamed and 1.1 ± 0.6 for healthy subcutaneous adipose tissue (P = 0.60) with a mean difference of 0.09 (95% CI −0.58, 0.76, P > 0.35).

Discussion

Recent data indicate that tissue penetration of antimicrobials may be substantially impaired in a variety of clinical settings. In particular, decreased blood flow has been shown to result in diminished ciprofloxacin tissue concentrations in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease [17]. This effect was reversible after percutaneous transluminal angioplasty [17]. Microdialysis studies have demonstrated that systemic and local inflammation substantially influences distribution of antimicrobial agents into soft tissues [6, 18]. Accumulation of fibrin and other proteins, oedema, changed pH and altered capillary permeability may result in local penetration barriers for drugs [4, 15]. Thus, tissue penetration of the free, pharmacologically active fraction of drugs was found to be markedly decreased by systemic inflammation in septic patients and local inflammation in diabetic patients [2, 6, 19]. Furthermore, inadequate or subinhibitory concentrations of antimicrobial agents at the target site may be associated with insufficient bacterial killing [20], a lack of clinical improvement and the emergence of resistant bacteria [9].

Accordingly we investigated the influence of local inflammation on target site pharmacokinetics of levofloxacin in patients suffering from soft tissue infections. We found that the levofloxacin concentrations vs time profiles for inflamed and healthy subcutaneous adipose tissue resemble closely those of free levofloxacin in plasma. Whereas the mean time-concentration profiles of levofloxacin in tissues and plasma were almost identical, considerable interindividual differences in pharmacokinetics in tissues and plasma were observed. This finding strengthens the hypothesis that high interindividual differences in plasma to tissue equilibration are to be expected among patients with soft tissue infections. The high variability might be explained by patients not being preselected prior to inclusion into the study. Chronic soft tissue infections are frequently characterized by necrotic and poorly perfused areas, whereas acute infections are mostly hyperaemic and well perfused. However, the small sample size of only six patients available for pharmacokinetic analysis in tissue precludes any subgroup analysis.

Levofloxacin penetrates well into healthy and inflamed soft tissues. Similar findings were reported in previous microdialysis studies with other fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin [21, 22]. No significant effect of local infection on tissue penetration was detected for these two drugs [21, 22]. Other methods such as skin biopsy have reported tissue to plasma ratios of around 2 [23, 24]. In lung resections ciprofloxacin concentrations exceeded corresponding plasma concentrations by more than sevenfold [25]. In biopsy samples, the drug is extracted from homogenized tissue comprising cells, extracellular matrix and extracellular space fluid, whereas microdialysis allows for the exclusive determination of concentrations of antibiotics in the interstitial space fluid [12, 13]. For drugs that accumulate intracellularly, the biopsy method overestimates effective drug concentrations in the interstitial space fluid, which represents the anatomical site for most bacterial infections [3]. In addition, only total levofloxacin concentrations can be obtained by biopsy methods, whereas the free drug fraction is pharmacologically active [13] and is determined by microdialysis. Inflammatory reactions may alter protein binding making free drug concentrations at the site of infection difficult to predict. Thus, the measurement of free levofloxacin concentrations in tissues provides more reliable data on effective drug concentrations at the relevant target site.

For the prediction of antimicrobial efficacy of fluoroquinolones, total plasma concentrations are used and the peak concentration (Cmax) divided by the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC; Cmax/MIC) and the AUC from 0 to 24 h divided by the MIC (AUC(0,24 h)/MIC) of the respective pathogen are commonly calculated. An AUC(0,24 h) : MIC ratio of more than 100 and a Cmax : MIC ratio of 8–10 are considered optimal for bacterial killing for fluoroquinolones [16, 27]. In a recent study, more than 85% of 2742 Streptococcus pyogenes strains isolated from skin, soft tissue or respiratory tract presented MIC values of 0.5 µg ml−1 or less, and 33% had an MIC value of not more than 0.25 µg ml−1[28]. Using a mean AUC(0,24 h) value of 52 mg l−1 h (Table 2) and calculating the AUC(0,24 h) : MIC ratio with a given breakpoint value of 0.5 µg ml−1, then effective killing can be expected. However, high interindividual differences in plasma to tissue equilibration were detected. Therefore, some cases of clinical and microbial failure might be explained by low individual tissue penetration, although the MIC of the pathogen is covered by the mean pharmacokinetic profile.

In summary, equilibration between free concentrations of levofloxacin in plasma and those in subcutaneous adipose tissue was unaffected by local inflammation. However, high interindividual variability in the extent of tissue penetration of levofloxacin was observed. Following IV administration of the standard dose of 500 mg levofloxacin adequate target site concentrations were reached. Nevertheless, tissue pharmacokinetics should be assessed in treatment resistant patients.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to our study nurses Edith Lackner and Petra Zeleny for their essential contributions to the study.

This work was not supported by any external funding.

References

- 1.Brunner M, Hollenstein U, Delacher H, et al. Distribution and antimicrobial activity of ciprofloxacin in human soft tissues. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1307–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.5.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joukhadar C, Frossard M, Mayer BX, et al. Impaired target site penetration of beta-lactams may account for therapeutic failure in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:385–91. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryan DM. Pharmacokinetics of antibiotics in natural and experimental superficial compartments in animals and humans. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31(Suppl D):1–16. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.suppl_d.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joukhadar C, Derendorf H, Müller M. Microdialysis. A novel tool for clinical studies of antiinfective agents. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57:211–9. doi: 10.1007/s002280100301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joukhadar C, Klein N, Mayer BX, et al. Plasma and tissue pharmacokinetics of cefpirome in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1478–82. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200207000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joukhadar C, Stass H, Müller-Zellenberg U, et al. Penetration of moxifloxacin into healthy and inflamed subcutaneous adipose tissues in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3099–103. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3099-3103.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Legat FJ, Maier A, Dittrich P, et al. Penetration of fosfomycin into inflammatory lesions in patients with cellulitis or diabetic foot syndrome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:371–4. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.371-374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tegeder I, Schmidtko A, Bräutigam L, Kirschbaum A, Geisslinger G, Lötsch J. Tissue distribution of imipenem in critically ill patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;71:325–33. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.122526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas JK, Forrest A, Bhavnani SM, et al. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of factors associated with the development of bacterial resistance in acutely ill patients during therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:521–7. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wagner FW. The dysvascular foot. a system for diagnosis and treatment. Foot Ankle. 1981;2:64–122. doi: 10.1177/107110078100200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lönnroth P, Jansson PA, Smith U. A microdialysis method allowing characterization of intercellular water space in humans. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:E228–31. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1987.253.2.E228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Müller M, Haag O, Burgdorff T, et al. Characterization of peripheral-compartment kinetics of antibiotics by in vivo microdialysis in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2703–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Müller M, Schmid R, Georgopoulos A, Buxbaum A, Wasicek C, Eichler HG. Application of microdialysis to clinical pharmacokinetics in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995;57:371–80. doi: 10.1016/0009-9236(95)90205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neckel U, Joukhadar C, Frossard M, Jäger W, Müller M, Mayer BX. Simultaneous determination of levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin in microdialysates and plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Chim Acta. 2002;463:199–206. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergogne-Bérézin E. Clinical role of protein binding of quinolones. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41:741–50. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200241100-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.North DS, Fish DN, Redington JJ. Levofloxacin, a second-generation fluoroquinolone. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18:15–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joukhadar C, Klein N, Frossard M, et al. Angioplasty increases target site concentrations of ciprofloxacin in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;70:532–9. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.120762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunner M, Pernerstorfer T, Mayer BX, Eichler HG, Müller M. Surgery and intensive care procedures affect the target site distribution of piperacillin. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1754–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200006000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joukhadar C, Klein N, Dittrich P, et al. Target site penetration of fosfomycin in critically ill patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:1247–52. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeitlinger M, Dehghanyar P, Mayer BX, et al. The relevance of individual soft tissue penetration of levofloxacin on target site bacterial killing in septic patients. Antimicrob Agents and Chemother. 2003. pp. 3548–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Müller M, Brunner M, Hollenstein U, et al. Penetration of ciprofloxacin into the interstitial space of inflamed foot lesions in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2056–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.8.2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Müller M, Stass H, Brunner M, Moller JG, Lackner E, Eichler HG. Penetration of moxifloxacin into peripheral compartments in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2345–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.10.2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chow AT, Chen A, Lattime H, et al. Penetration of levofloxacin into skin tissue after oral administration of multiple 750 mg once-daily doses. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:143–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Licitra CM, Brooks RG, Sieger BE. Clinical efficiency and levels of ciprofloxacin in tissue in patients with soft tissue infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemotherapy. 1987;31:805–7. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.5.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birmingham MC, Guarino R, Heller A, et al. Ciprofloxacin concentrations in lung tissue following a single 400 mg intravenous dose. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43(Suppl A):43–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.suppl_1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kunin CM, Craig WA, Kornguth M, Monson R. Influence of binding on the pharmacologic activity of antibiotics. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1973;226:214–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1973.tb20483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turnidge J. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of fluoroquinolones. Drugs. 1999;58(Suppl 2):29–36. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958002-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forrest A, Nix DE, Ballow CH, Goss TF, Birmingham MC, Schentag JJ. Pharmacodynamics of intravenous ciprofloxacin in seriously ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1073–81. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]