Abstract

Aims

We prospectively studied the efficacy, incidence of adverse drug reactions and withdrawal from leflunomide in an outpatient population with rheumatoid arthritis in a setting of care-as-usual.

Methods

In this prospective case series study, from outpatient medical records a standard dataset was collected including patient and disease characteristics, data on leflunomide use and adverse drug reactions.

Results

During the study period 136 rheumatoid arthritis patients started leflunomide. Median (range) follow-up duration was 317 (11–911) days. Sixty-five percent of patients experienced at least one adverse drug reaction related to leflunomide. During follow-up 76 patients (56%) withdrew from leflunomide treatment, mainly because of adverse drug reactions (29%) or lack of efficacy (13%). The overall incidence density for withdrawal from leflunomide was 56.2 per 100 patient-years. Complete data for calculating efficacy using a validated disease activity score on 28 joints (DAS28) was available for 48, 36, and 35% of patients at 2, 6, and 12 months follow-up, respectively. Within a 12-month period after start of leflunomide treatment 76% of the evaluable patients were classified as moderate or good responders according to the DAS28 response criteria.

Conclusions

In the setting of care-as-usual, rheumatoid arthritis patients starting leflunomide frequently experienced adverse drug reactions. More than half of the patients withdrew from leflunomide treatment within a year after start of leflunomide treatment, mainly because of adverse drug reactions.

Keywords: leflunomide, rheumatoid arthritis

Introduction

In January 2000 leflunomide was registered in the Netherlands for treating active rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Leflunomide represents a novel class of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD), the isoxazole derivatives. The active metabolite, A77 1726, reversibly inhibits the enzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, the rate limiting step in the de novo synthesis of pyrimidines [1]. Hypotheses on the pathogenesis of RA suggest an important role of activated T lymphocytes [2]. Since lymphocytes are dependent on de novo synthesis of pyrimidines for their cell division, proliferation of lymphocytes is inhibited by A77 1726.

Efficacy and safety of leflunomide have been demonstrated in randomized controlled trials that included over 1000 RA patients treated with leflunomide [3–10]. These trials demonstrate similar efficacy of leflunomide in suppressing RA compared to sulphasalazine and methotrexate (MTX) after 6 months to 2 years of follow-up [3–7]. By inclusion of patients based on selection criteria and strict follow-up, the trial setting is different from daily clinical practice in rheumatology. This difference between research trial and day-to-day practice may limit the validity of extrapolation of data from these trials to RA patients in daily practice [11]. Therefore, studies on clinical experience in daily practice with newly approved therapies are important to inform about potential discrepancies with the results from randomized controlled trials.

In this study we evaluated the efficacy, safety and withdrawal rates for leflunomide in an outpatient RA population treated with usual care.

Methods

Patients and inclusion criteria

All consecutive RA patients to whom leflunomide was prescribed de novo by their rheumatologist in the outpatient departments of rheumatology in Friesland (in the Northern part of the Netherlands) from January 2000 to June 2002 were included. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Medical Centre Leeuwarden. Patients signed informed consent for collecting a standard dataset using outpatient medical records, and were followed from the start of leflunomide until the end of the study, withdrawal from leflunomide, or death.

Patients were recorded as ‘lost to follow-up’ where the last visit to the outpatient rheumatology department was more than 1 year ago.

Data collection

The standard dataset, using outpatient medical records, consisted of patient characteristics, disease characteristics, adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and leflunomide use data. During the study period information on leflunomide treatment in combination with other DMARDs was scarce. However, to gain insight into combination of leflunomide with other DMARDs or systemic corticosteroids, data on comedication were recorded in the study database.

Intensity of follow-up of the patients during this study was similar to nonstudy patients, reflecting care-as-usual. Patients visited the rheumatologist on a routine basis at least every month up to 6 months after start of leflunomide treatment and every 2 months thereafter. During these visits a routine physical examination was conducted, parameters for calculation of the disease activity score on 28 joints (DAS28) were scored, and ADRs were collected. In case of intercurrent problems, patients contacted the outpatient department by telephone. In the outpatient medical records all telephone contacts were registered.

An exception to the rule of care-as-usual was made for registration of parameters necessary for calculation of the DAS28, a validated score for establishing disease activity and response to therapy in rheumatoid arthritis [12, 13]. The DAS28 is calculated from four parameters: the number of swollen and tender joints from a total of 28 joints, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and the visual analogue score for general health as subjectively estimated by the patient. High, moderate or low disease activity is categorized as DAS28 scores >5.1, >3.2 but ≤5.1 and >2.6 but ≤3.2, respectively. Remission is categorized as DAS28 scores ≤2.6 [12]. Response to treatment according to DAS28 is defined by both the difference in DAS28 and the DAS28 achieved (Table 1).

Table 1.

Definition of DAS28 responder categories

| Change in DAS28 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| DAS28 achieved | >1.2 | >0.6–≤1.2 | ≤0.6 |

| ≤3.2 | Good | Moderate | Non |

| 3.2–5.1 | Moderate | Moderate | Non |

| >5.1 | Moderate | Non | Non |

DAS28 calculation: DAS28 = 0.56 × √TJS28 + 0.28 × √SJS28 + 0.70 × ln ESR + 0.014 VASgeneral health DAS28, Disease activity score for 28 joints; TJS28, tender joint score for 28 joints; SJS28, swollen joint score for 28 joints; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm hr−1); VAS, visual analogue scale (mm).

To avoid bias of DAS28 on treatment decisions during the study period, DAS28 was calculated from the individual parameters only at the end of the follow-up. Due to possible incompleteness of DAS28 data, we predefined the category of evaluable patients for response on leflunomide treatment as patients for whom a DAS28 at start of leflunomide, and at least one follow-up DAS28 in the first 12 months of leflunomide treatment were available. DAS28 response was categorized comparing the DAS28 at start of leflunomide treatment with the lowest DAS28 achieved during the first 12 months.

During each follow-up visit patients were asked about ADRs. When an ADR or abnormal biochemical parameter was encountered and judged by the rheumatologist or patient as possibly related to leflunomide, then the ADR was recorded. Different ADRs reported by one patient, although possibly related to each other, were recorded as separate ADRs (e.g. weight loss in combination with loss of appetite, nausea or vomiting). Serious ADRs were predefined as fatal, life-threatening, permanently disabling or necessitating hospital admission.

Withdrawal from leflunomide was defined as any reported discontinuation of leflunomide use. In the study database the reasons for withdrawal from leflunomide treatment were recorded using the information in the medical record. If no specific reason for withdrawal was mentioned, this was recorded as such in the study database.

In case of restarting leflunomide, patients were not eligible for re-entry into this study. To detect restart of leflunomide, patients were followed for another 12 weeks after withdrawal from leflunomide.

Leflunomide treatment

The place of leflunomide in the sequence of DMARD therapy in RA is not standardized, and was left to the judgement of the individual rheumatologist. Leflunomide was prescribed in a dose as recommended by the manufacturer, i.e. loading dose of 100 mg daily for 3 days, followed by 20 mg daily.

Statistical analysis

Access database software (Microsoft Corp., Seattle, WA, USA) was used for data collection, data validation and data selection. SPSS 10.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for statistical analysis. For survival analysis the Kaplan–Meier estimator was used to calculate the cumulative probability of withdrawal from leflunomide.

Results

Population

All consecutive RA patients to whom leflunomide was prescribed during the study period were included, giving a study population of 136 patients. Reasons for starting leflunomide were: ADRs on previous DMARD therapy (n = 26; 19%), inefficacy of previous DMARD (n = 63; 46%), or a combination of these reasons (n = 17; 13%). For three (2%) patients the specific reason for starting leflunomide was not registered in the files and 27 patients (20%) started leflunomide as the first DMARD.

Table 2 shows baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of our study population and characteristics from the populations from the major randomized controlled trials [3–5]. Median (range) follow-up duration was 317 (11–911) days. Three patients died during follow-up from natural causes, i.e. not related to leflunomide use, and eight patients were lost to follow-up.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the present study population compared with [3–5]

| Demographic characteristics | Present study | [3]* | [4] | [5] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 136 | 133 | 182 | 501 | |

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 65 (13) | 58 (11) | 54 (12) | 58 (10) |

| Range | 27–89 | ||||

| > 65 years (%) | 47 | 31 | |||

| Female (%) | 66 | 76 | 73 | 71 | |

| Rheumatoid factor positive (%) | 80 | 79 | 65 | ||

| Duration of RA (years) | Mean (SD) | 9.7 (11.2) | 7.6 (8.6) | 7.0 (8.6) | 3.7 (3.2) |

| Range | 0.1–60 | ||||

| ≤ 2 years (%) | 33 | 38 | 39 | 44 | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Previous DMARD treatment (%) | 76 | 60 | 56 | 66 | |

| DMARDs failed (n) | Mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.5) | 1.2 | 0.8 (1.0) | 1.1 (1.1) |

| Range | 0–6 | ||||

| DAS28 | Mean (SD) | 5.25 (1.01) | |||

| Median (range) | 5.32 (2.4–8.4) | ||||

| Last DMARD prior to leflunomide, n (%) | Methotrexate | 40 (30) | |||

| Sulphasalazine | 28 (22) | ||||

| Hydrochloroquine | 22 (17) | ||||

| Other | 14 (10) | ||||

| Concomitant systemic corticosteroids, n (%) | 59 (43) | 29 | 54 | 36 | |

| < 7.5 mg prednisone equivalents daily | 46 (33) | ||||

| ≥ 7.5 mg prednisone equivalents daily | 13 (10) | ||||

DMARD, Disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; SD, standard deviation.

Data after 12 months' follow-up.

Four patients (3%) started leflunomide in combination with MTX in order to bridge the first months, in which leflunomide was not expected to show optimal efficacy. Three of these patients were withdrawn from MTX within 6 months after start of leflunomide as planned, and one patient continued using the combination. For 15 patients (11%) another DMARD was added to leflunomide treatment (8 × MTX, 5 × hydrochloroquine, 1 × sulphasalazine, 1 × infliximab) during follow-up. Of these patients, seven withdrew from leflunomide [three for reasons of adverse drug reaction (all MTX combinations), two inefficacy (one MTX and one sulphasalazine combination) and two combination of ADR and inefficacy (both MTX combination)], two were lost to follow-up, and one patient died.

Efficacy and adverse drug reactions

Due to incomplete data for calculating DAS28, disease activity and response category data were not available for every patient at every visit. At baseline for 79 of 136 patients (58%) a DAS28 could be calculated. Complete DAS28 data were available for 48, 36, and 35% of patients at 2, 6, and 12 months’ follow-up, respectively.

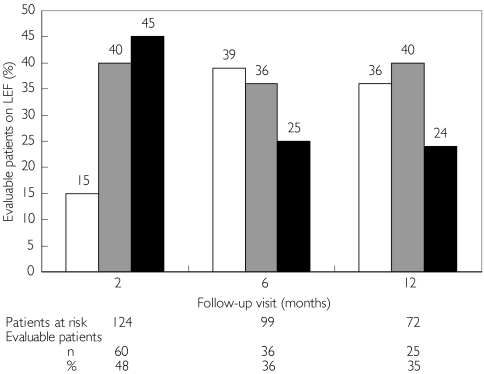

Ninety-eight percent of the evaluable patients had high or moderate disease activity according to DAS28 criteria at baseline. Two percent of the patients started leflunomide treatment with a baseline DAS28≤2.6. Responder categories according to DAS28 criteria at the 2, 6 and 12-month follow-up visits are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Disease activity score on 28 joints (DAS28) responders at 2-, 6- and 12-months’ follow-up visit (% of patients). Good responders (□); moderate responders (□); nonresponders (▪). 1Due to missing DAS28 scores the number of patients that can be evaluated is lower than the number at risk

During follow-up in 89 patients (65%) at least one ADR was registered. Table 3 lists the ADRs reported by three or more patients (> 2%) during follow-up. All patients reporting weight loss also reported loss of appetite or diarrhoea. Loss of appetite does not seem to be directly correlated to other gastrointestinal complaints, since only three of six patients who reported loss of appetite also reported diarrhoea (3 ×) and/or nausea (1 ×).

Table 3.

Percentage of patients reporting adverse drug reactions (> 2% of patients in present study) and associated withdrawal rates, in comparison with [4, 5]

| Present study | [4] | [5] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADR | Withdrawal | ADR | ADR | ||||

| n | % | % | % | Withdrawal | % | Withdrawal | |

| Withdrawal (per patient-yearfollow-up) | |||||||

| Overall | 56.2 | 30 | 47 | ||||

| ADR | 29.6 | 19 | 22 | ||||

| Inefficacy | 12.6 | 7 | 4 | ||||

| ADR/Inefficacy | 7.4 | ||||||

| Other | 6.7 | 4 | 8 | ||||

| ADR | |||||||

| Diarrhoea | 40 | 29.4 | 18.4 | 33.5 | 5.5* | 18 | 2 |

| Nausea | 15 | 11.0 | 5.9 | 20.9† | 11.2 | 1.2 | |

| Pruritus | 10 | 7.4 | 4.4 | ||||

| Hypertension | 9 | 6.6 | 4.4 | 11 | 1.1 | ||

| Skin problems‡ | 8 | 5.9 | 3.7 | 2.2 (rash) | 7.4 (rash) | 1.2 (rash) | |

| Alopecia | 7 | 5.1 | 2.9 | 9.9 | 0.5 | 16.6 | 1.4 |

| Gastrointestinal pain | 7 | 5.1 | 2.2 | 13.7 | 5.6 | 0.8 | |

| Abnormal enzyme elevations§ | 6 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 11 | 7.1 | 5.4 | 1.6 |

| Loss of appetite | 6 | 4.4 | 2.2 | ||||

| Headache | 4 | 2.9 | 1.5 | 6.2 | 0.6 | ||

| Vomiting | 3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | ||||

| Hoarseness | 3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | ||||

| Weight loss | 3 | 2.2 | 1.5 | ||||

| Mouth ulceration | 3 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 0.2 | |

Withdrawal for all gastrointestinal ADR.

Nausea and vomiting.

ADR skin events reported (n): eczema (2), rash (2), psoriasis (1), urticaria (1), dry skin (1), not specified (1).

Abnormal plasma liver enzyme levels are defined as ALAT or ASAT values >2 x upper limit of normal values, reference [5] >3 x upper limit of normal values. ADR, Adverse drug reaction.

For one patient a serious adverse event was recorded leading to hospitalization. This patient, who was one of the nine patients developing hypertension, suffered an ischaemic cerebrovascular accident during leflunomide treatment.

Additionally, the following ADRs were reported with a frequency of <2% of the patient population: fatigue (n = 2), polyuria, nocturnal enuresis, tinnitus, dry mouth, constipation, palpitations, dry eyes, lightheadedness, tremor, excessive perspiration, anxiety, swollen lips, muscle cramps in lower legs, coughing, nailfold lesions, thrombocytopenia (nadir 75 × 109 l−1), and dizziness (all n = 1).

Withdrawal from leflunomide

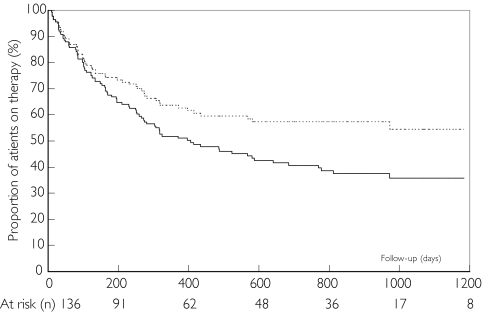

During follow-up 76 patients (56%) withdrew from leflunomide treatment. Fifty percent of study patients withdrew from leflunomide within 405 days. The incidence density for withdrawal from leflunomide was 56.2 per 100 patient-years. Figure 2 shows Kaplan–Meier estimates of the proportion of patients withdrawing from leflunomide during follow-up. Reasons for withdrawal from leflunomide were ADRs (n = 40; 29%), inefficacy or loss of efficacy (n = 17; 13%), or a combination of ADR and insufficient efficacy (n = 10; 7%). Two patients (1.5%) stopped leflunomide for comorbidity not related to leflunomide treatment (sepsis, toxic megacolon). For seven patients (5%) no specific reason for stopping leflunomide was recorded. Table 3 shows the frequencies of withdrawal from leflunomide for ADRs recorded for three or more (> 2%) of patients during follow-up in our study and two randomized controlled trials with 12-month follow-up data [4, 5].

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier for withdrawal from leflunomide use. Total withdrawal from leflunomide (———); withdrawal from leflunomide due to adverse drug reactions (- - - - -)

Within 12 weeks after withdrawal from leflunomide seven patients out of 76 (9%) restarted leflunomide, and six of these patients were still on leflunomide treatment at the moment of closing the study database (January 2003). Reasons for stopping leflunomide before restarting at a later date were ADR for four patients, inefficacy for one patient, and a combination of ADRs and inefficacy for two patients.

Discussion

Data from randomized controlled trials are obtained from selected populations in the setting of a strict follow-up. A follow-up study of patient populations outside the setting of a randomized controlled trial is an important tool to learn about drug efficacy and safety in daily clinical practice. Leflunomide has become available for the treatment of RA in a period of new treatment possibilities and a changing treatment algorithm. Early treatment of RA with DMARDs [14], the availability of tumour necrosis factor-alpha antagonists [15, 16] and the use of DMARDs in combination therapy [17] highlight the need for careful evaluation of new treatment options. In this study we followed an outpatient population that started leflunomide for the treatment of RA in the setting of care-as-usual.

Some remarks should be made on the limitations of the present study. First, due to missing data DAS28 scores could be calculated for only 35–58% of the patients on leflunomide therapy at every visit. Although we expected some incompleteness of DAS28 data before start of the study and we prospectively defined patients that could be evaluated, the influence of missing data on overall response rates is not clear. The percentage of DAS28-non-evaluable patients reflects one of the basic concepts of the study. In our study we followed an outpatient population of patients, consecutively starting leflunomide treatment for their RA in a setting of care-as-usual. Since optimization of completeness of DAS28 data would require serious interference with the concept of care-as-usual, and therefore with clinical decision making, it was explicitly decided at the start of the study not to interfere during follow-up.

Second, this study was conducted in the period immediately following leflunomide licensing for the treatment of RA. The role of leflunomide in the treatment algorithm of RA is not yet defined and may well change in time. This is illustrated by the results of studies combining leflunomide with MTX [8, 18]. This changing place of leflunomide in the treatment of RA may have consequences for patient outcomes in terms of treatment efficacy or safety and the applicability of our study results in the future.

At baseline 98% of our evaluable study population had high or moderate RA disease activity according to DAS28 criteria [12]. This percentage reflects high adherence of the rheumatologists to the approved indication of leflunomide for adult patients with active RA. During the first 12 months of follow-up the percentage of nonresponders per visit varied from 24 to 45%. Despite this large percentage of non-effective treatment, overall only 13% withdraw from leflunomide treatment because of inefficacy. This discrepancy may be explained by the fact that DAS28 scores are not used in routine clinical practice in our centre as key parameter for treatment efficacy. Another explanation may be the strategy of postponing withdrawal in the expectation of efficacy later during treatment. This strategy is supported by data from recent studies. Results of randomized controlled trials [3, 4] show improvement of disease severity characteristics for an increasing percentage of the study population in the period from 3 to 6 months after start of leflunomide treatment. Dougados et al. [19] in their 6-month follow-up data from the RELIEF study show an increase of 56.0–77.1% in patients achieving a ‘definitive’ responder rate at weeks 12 and 24 of leflunomide treatment, respectively.

Comparison of our results with randomized controlled trials, Strand et al. [4] and Emery et al. [5] in their studies found 52% and 50.5%, respectively, of patients reaching 20% improvement according to criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR20), after 12 months. In our study 76% of evaluable patients showed moderate or good response at 12-month follow-up according to DAS28 criteria. Although degrees of responder categories according to DAS28 and ACR20 criteria correlate well [20, 21], comparison of our results with randomized controlled trials is not possible due to incompleteness of our data on DAS28 scores.

In the past few years, despite the availability of leflunomide and the biologicals, the treatment algorithm for RA did not change significantly. Therefore, the place of leflunomide in the treatment strategy of RA in the past few years was often secondary to other DMARDs. Its place in therapy is reflected by the baseline characteristics of our study population.

Compared with the population included in the randomized controlled trials on leflunomide, our population was older, had a longer duration of RA, and was more frequently and more intensively treated with DMARDs before start of leflunomide (Table 2). Major inclusion criteria from the randomized controlled trials were a duration of RA >4–6 months [4, 5], an age >18 years, active disease, and no concomitant DMARD therapy [3–5]. Concomitant use of systemic corticosteroids (≤ 10 mg prednisolone daily or equivalent) was allowed if doses were stable for 4 weeks previous to leflunomide start. In our study at baseline 89% of patients had a disease duration >4 months, all patients were >18 years of age (range 27–89), 98% had active disease and 86% used leflunomide as the only DMARD during complete follow-up. In our population 30% of patients switched from MTX to leflunomide. In contrast, in the study by Strand et al. [4] patients who were pretreated with MTX were not eligible. This pretreatment with MTX could influence comparability of data with the present study. However, MTX pretreatment as risk factor for early leflunomide withdrawal or reduced efficacy has not been published to our knowledge. Overall, the inclusion and exclusion criteria used in the randomized controlled trials [3–5] are not different from the characteristics in the present study population.

The ADRs reported in our study are in general comparable with those reported in randomized controlled trials. However, in our study hoarseness and loss of appetite (independent of other gastrointestinal complaints) are reported in >2% of patients. These ADRs are not reported in the randomized controlled trials [3–5].

Compared with randomized controlled trials with approximately the same duration of follow-up as the present study [4, 5], the overall withdrawal rate was high in our study, 56.2 per 100 patient-years (Table 3). Withdrawal due to ADRs represents approximately 50% of the overall withdrawal rate both in our study and in the randomized controlled trials.

Results of studies outside the setting of randomized controlled trials show high withdrawal rates for leflunomide treatment. Geborek et al. [22] report withdrawal from leflunomide treatment of 78% of patients after 20 months' follow-up. Siva et al. [23] and Hajidiacos et al. [24] report withdrawal rates of 63% and 78%, respectively, after 6 months of follow-up. After 12 months withdrawal rates of 48% [24] and 57% [25] have been reported. Wolfe et al. [26] report failure rates of 55.5% per 100 patient-years' follow-up. The results from these observational studies and the present study suggest that the withdrawal rate from leflunomide treatment is higher in the setting of care-as-usual compared with randomized controlled trials.

The high withdrawal rates demand optimization of the leflunomide treatment schedule and better recognition of patients at risk of treatment failure. Possibilities for improvement of the treatment schedule include omitting the loading dose, weekly dosing, and/or titration of the leflunomide dose on the basis of the plasma concentrations of the active metabolite, A77 1726.

Siva et al. [23] present evidence for the higher risk (odds ratio 2.0, CI 1.76, 2.4) of leflunomide treatment failure after start with the 3 × 100-mg loading dose compared with no loading or other loading schemes. Erra et al. [27] in their study conclude a potential association between the loading dose and early adverse events. Several studies investigated weekly dosing of leflunomide [28, 29]. Although these studies are small and have a short duration of follow-up, the results suggest that weekly dosing of leflunomide is effective and well tolerated.

The relationship between mean steady-state plasma concentrations of A77 1726 and the probability of clinical succes [30] suggests options for therapeutic drug monitoring and dose titration. Since leflunomide dosing is limited to 20 mg daily with possible dose reduction to 10 mg [31], at the moment the possibilities for dose adjustment are scarce. On the basis of study results thus far, the above-mentioned options for adaptation of the dosing schedule of leflunomide have to be explored in future research in order to optimize leflunomide treatment.

Conclusion

Leflunomide offers an efficacious treatment option, although the incidence of withdrawal from leflunomide therapy in the present study was high. ADRs are the most frequently encountered reason for withdrawal. The results of this study stress the importance of critical evaluative studies in the positioning of a novel DMARD in the setting of care-as-usual.

Acknowledgments

J. Collins is gratefully acknowledged for critical comments during the preparation of the manuscript. Interim results were presented at the EUropean League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) congress, Prague, Czech Republic, June 15, 2001.

References

- 1.Breedveld FC, Dayer J-M. Leflunomide: mode of action in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:841–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.11.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steiner G, Tohidast-Akrad M, Witzmann G, et al. Cytokine production by synovial T cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 1999;38:202–13. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.3.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smolen JS, Kalden JR, Scott DL, et al. Efficacy and safety of leflunomide compared with placebo and sulphasalazine in active rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet. 1999;353:259–66. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)09403-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strand V, Cohen S, Schiff M, et al. Treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis with leflunomide compared with placebo and methotrexate. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2542–50. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.21.2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Lemmel EM, et al. A comparison of the efficacy and safety of leflunomide and methotrexate for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol. 2000;39:655–65. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.6.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalden JR, Scott DL, Smolen JS, et al. Improved functional ability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis—longterm treatment with leflunomide versus sulfasalazine. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1983–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen S, Cannon GW, Schiff M, et al. Two-year, blinded, randomized, controlled trial of treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis with leflunomide compared with methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1984–92. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200109)44:9<1984::AID-ART346>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinblatt ME, Kremer JM, Coblyn JS, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of combination treatment with methotrexate and leflunomide in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1322–8. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199907)42:7<1322::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharp JT, Strand V, Leung H, Hurley F, Loew-Friedrich I. Treatment with leflunomide slows radiographic progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:495–505. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200003)43:3<495::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kraan MC, Reece RJ, Barg EC, et al. Modulation of inflammation and metalloproteinase expression in synovial tissue by leflunomide and methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1820–30. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1820::AID-ANR18>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black N. Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care. Br Med J. 1996;312:1215–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7040.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prevoo ML, van Gestel AMT, 't Hof MA, van Rijswijk MH, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Remission in a prospective study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. American Rheumatism Association preliminary remission criteria in relation to the disease activity score. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:1101–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.11.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Gestel AM, van Prevoo MLL, 't Hof MA, et al. Development and validation of the European League against Rheumatism reponse criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:34–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Collega of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Clinical Guidelines. Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:713–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreland LW, Schiff MH, Baumgartner SW, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:478–86. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, et al. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1594–602. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris ED. Rationale for combination therapy of rheumatoid arthritis based on pathophysiology. J Rheumatol. 1996;23(44):2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kremer JM, Genovese MC, Cannon GW, et al. Concomitant leflunomide therapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis despite stable doses of methotrexate. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:726–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-9-200211050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dougados MAC, Emery P, Lemmel EM, et al. Efficacy and safety of leflunomide and predisposing factors for treatment response in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis—RELIEF 6-month data. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2572–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Gestel AM, Anderson J, Van Riel PLCM, et al. ACR and EULAR improvement criteria have comparable validity in rheumatoid arthritis trials. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:705–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smolen JS, Breedveld F, Schiff MH, et al. A simplified disease activity index for rheumatoid arthritis for use in clinical practice. Rheumatol. 2003;42:244–57. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geborek P, Crnkic M, Petersson IF, et al. Etanercept, infliximab, and leflunomide in established rheumatoid arthritis: clinical experience using a structured follow-up programme in southern Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:793–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.9.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siva C, Eisen SA, Shepherd R, et al. Leflunomide use during the first 33 months after food and drug administration approvalexperience with a national cohort of 3,325 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:745–51. doi: 10.1002/art.11452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hajidiacos NP, Robinson DB, Peschken CA. Leflunomide in Clinical Practice: Two-Year Population-Based Data with Clinical Validation. New Orleans, Louisiana: American College of Rheumatology 66th Annual Scientific Meeting; 2002. 25–29 October, (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brault I, Gossec L, Pham T, Dougados M. Leflunomide Termination Rates in Comparison with Other Dmards in Rheumatoid Arthritis. New Orleans, Louisiana: American College of Rheumatology 66th Annual Scientific Meeting; 2002. 25–29 October, (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfe F, Michaud K, Stephenson B, Doyle J. Toward a definition and method of assessment of treatment failure and treatment fffectiveness: the case of leflunomide versus methotrexate. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1725–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erra A, Moreno E, Tomas C, et al. Efficacy and safety of leflunomide in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Relationship between adverse drug reactions and loading dose. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(Suppl 1):379. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jakez-Ocampo J, Richaud-Patin Y, Simon JA, Llorente L. Weekly dose of leflunomide for the treatment of refractory rheumatoid arthritis: an open pilot comparative study. Joint Bone Spine. 2002;69:307–11. doi: 10.1016/s1297-319x(02)00397-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaimes-Hernandez J, Suarez R. Rheumatoid arthritis treatment with weekly leflunomide: an open-label study. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:235–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Population Pharmacokinetic Report, Leflunomide. Geneva, Switzerland: Hoechstmarion-Roussel; 1997. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arava™ (Leflunomide) Product monograph. Bridgewater, NY: Aventis; 2000. pp. 11–3. [Google Scholar]