Abstract

Aim

This study evaluated the safety and pharmacokinetics (PK) of donepezil HCl and sertraline HCl when administered separately and in combination.

Methods

This was a randomized, open-label, three-period crossover study. In consecutive dosing periods separated by washout periods of ≥3 weeks, healthy volunteers received either oral donepezil HCI 5 mg once daily for 15 days, oral sertraline HCl 50 mg once daily for 5 days followed by 10 days of once-daily sertraline HCl 100 mg, or the simultaneous administration of oral donepezil HCl and sertraline HCl. Plasma donepezil and sertraline concentrations were determined by high performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Safety was evaluated by physical and laboratory evaluations and the monitoring of adverse events (AEs).

Results

A total of 19 volunteers (16 male and three female) were enrolled. Three male subjects withdrew from the study prematurely due to AEs (one case of nausea/stomach cramps and one case of eosinophilia during combination treatment, and one upper respiratory tract infection during treatment with sertraline HCl alone). In subjects who completed all three treatment periods (n = 16), the concurrent administration of donepezil HCl and sertraline HCl did not alter the steady-state (day 15) PK parameters of donepezil HCl. A small (<12%) but statistically significant (P = 0.02) increase in donepezil Cmax was seen after single doses of sertraline HCl and donepezil HCl on day 1 but this was not thought to be clinically meaningful. No significant differences in the tmax or AUC0–24 h of donepezil were observed between the donepezil HCl only or donepezil HCl plus sertraline HCl groups on day 1. No significant changes in sertraline PK parameters were observed either on day 1 (single dose) or on day 15 (steady state) when sertraline HCl was co-administered with donepezil HCl. Generally, the concurrent administration of donepezil HCl and sertraline HCl was well tolerated, with no serious AEs reported during the study. Some digestive system AEs tended to occur more frequently during combination treatment than with either treatment alone, but there was no statistically significant increase in the incidence of any individual AE. The most common AEs during the combination therapy were nausea and diarrhoea, which were rated as mild or moderate in severity. These AEs were also reported during the administration of each drug alone.

Conclusions

The co-administration of once-daily oral donepezil HCl 5 mg for 15 days and once-daily oral sertraline HCl (50 mg for 5 days increased to 100 mg for 10 days) did not result in any clinically meaningful pharmacokinetic interactions, and no unexpected AEs were observed.

Keywords: acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, Alzheimer's disease, donepezil, drug–drug interaction, pharmacokinetics, sertraline

Introduction

Although the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD) is poorly understood, there is wide consensus that a decline in neurotransmission in cholinergic pathways located in the cerebral cortex and basal forebrain of AD patients leads to the characteristic decline in cognition [1, 2]. Currently, the most effective symptomatic treatments for AD are cholinesterase (ChE) inhibitors, which have been developed to augment cholinergic function and to restore the physiological effect of acetylcholine within the cerebral cortex.

Donepezil HCl is a potent and specific piperidine-based inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [3], and has been demonstrated in placebo-controlled trials to significantly improve cognition, as well as maintaining global function and activities of daily living (ADLs) for up to a year [4–7]. In single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetic studies, donepezil has demonstrated a favourable pharmacokinetic (PK) profile, including a long plasma half-life (allowing once-daily dosing) and plasma concentrations that are linearly proportional to doses within the therapeutic range [8, 9], features that are similar in young and elderly patients [3]. Donepezil is primarily metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes 2D6 and 3A4 [10], and has minimal inhibitory activity against these isoenzymes [11], and a low potential to interact with drugs that inhibit CYP 2D6 and CYP 3A4, e.g. cimetidine and ketoconazole [11, 12]. As a cholinomimetic agent, donepezil increases the incidence of pharmacologically mediated adverse events (AEs), most notably in the gastrointestinal tract. However, the incidence of cholinergic side-effects is low at the clinically effective starting dose and is further minimized at the higher dose using the established dose schedule (5 mg day−1 for 4–6 weeks, then 10 mg day−1 according to tolerability) [4, 5].

There is a high incidence of co-morbid depression in patients with AD [13, 14], and accumulating evidence shows that this can have profound effects on both the long-term functioning of AD patients and the well-being of their caregivers [15]. Its treatment represents a further challenge in the management of AD, since antidepressant medications will often be co-administered with drugs for the treatment of AD symptoms [16, 17]. Sertraline HCl – a selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI) – is indicated for the treatment of depression and anxiety disorders, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. It is considered suitable for the treatment of depressive symptoms in elderly patients, including those with AD, as it has minimal anticholinergic activity and is essentially devoid of cardiovascular effects [18]. Furthermore, sertraline HCl may be useful in the management of other behavioural problems experienced by AD patients that are likely mediated by the serotonergic system, such as anxiety, irritability and aggression [19].

Like donepezil, sertraline has a low potential for CYP-mediated drug–drug interactions [20, 21]. Since there is some overlap in the pathways by which donepezil and sertraline are metabolized (CYP 2D6 and CYP 3A4), this study was carried out to determine any possible drug–drug interactions with the concurrent administration of donepezil HCl and sertraline HCl.

Methods

Subjects

Healthy, ambulatory adult men and nonpregnant women of any race, aged between 19 and 45 years, and weighing between 60 and 95 kg (within 20% of their ideal body weight) [22] were enrolled. None of the subjects had significant pathology or history of acute illness within 30 days of the start of the study. Subjects were excluded if they had a known or suspected history of alcohol or drug misuse, or a positive urine drug screen. Subjects who had recently undergone major surgery or donated blood within 1 month of the start of the study were also excluded. Subjects were not permitted to use tobacco or nicotine-containing products within 3 months prior to the start of the study. A positive serum hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) screen, or βHCG test were also reasons for exclusion. Subjects' CYP 2D6 genotypes were established (Gene Screen, Dallas, Texas) at baseline (day 0) to determine whether they were poor metabolizers or extensive metabolizers.

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to screening, and the study protocol was approved by the institutional review board and conducted in accordance with the principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Protocol

This was an open-label, single-centre, multiple-dose, three-period crossover study, in which healthy volunteers were randomly assigned to receive study medication in one of six treatment sequences according to an in-house generated randomization schedule (Biometrics Department, Eisai Inc.). Each treatment sequence comprised three dosing periods, during which the following study medication was administered: single oral doses of donepezil HCl once daily for 15 days; single oral doses of sertraline HCl once daily for 15 days; or a combination of oral doses of donepezil HCl and sertraline HCl once daily for 15 days.

Study medication was administered in the morning with 250 ml of tap water in six different permutations, as shown in Table 1. The first and last doses of medication within each dosing period were administered in the fasted state (fasted overnight before and for 4 h after study medication), and all liquids (including water) were restricted 1 h before and 4 h after administration. Dosing periods within each sequence were separated by a washout period of at least 3 weeks, which included 1 week of blood sample collection after the last dose of medication. All doses of donepezil HCl remained constant (5 mg day−1) throughout the dosing period. All sertraline HCl doses were initially 50 mg once daily for 5 days, and were then increased to 100 mg once daily from days 6 to 15. Steady-state sertraline levels should be achieved after approximately 1 week of once-daily dosing, due to its elimination half-life of 26 h [23]. Drug dosages were based on clinically effective doses of Aricept® (donepezil HCl) [4] and Zoloft® (sertraline HCl) [24].

Table 1.

Summary of dosing during treatment with donepezil HCl, sertraline HCl or donepezil HCl + sertraline HCl

| Treatment | Dosing period* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| sequence | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1 | D | S | D + S |

| 2 | D | D + S | S |

| 3 | S | D + S | D |

| 4 | S | D | D + S |

| 5 | D + S | D | S |

| 6 | D + S | S | D |

D = donepezil HCl; S = sertraline HCl.

Each dosing period lasted for 15 days and all dosing periods were separated by a washout period of at least 3 weeks.

During each dosing period throughout the study, subjects were not permitted to receive any medications other than the test drug, including prohibited prescription drugs (from within 30 days of the start of the study), investigational drugs, over-the-counter (OTC) products (from within 72 h of the start of the study), recreational drugs or alcohol. All other medications used at any time during the study were recorded, including the name of the product and the indication, dosage and duration of treatment. Food or drinks that were likely to significantly induce or inhibit hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes (e.g. grapefruit juice) were not allowed during each dosing period or 72 h before each study visit. Patients also abstained from physical exercise other than normal walking.

Sample collection and analysis

Blood samples were collected from subjects for measurement of plasma donepezil, 6-O-desmethyldonepezil (6-OH donepezil, the major active metabolite) and sertraline concentrations. On day 1 and day 15, samples were collected 1 h prior to and 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 18 and 24 h after the administration of study medication. Follow-up samples were taken 48, 72, 96, 120, 144 and 168 h after administration of the last dose of study medication. Additional samples for the measurement of trough concentrations of the two drugs were collected prior to dosing on days 8, 10, 12, 13 and 14.

At each blood sample collection, 7 or 14 ml of blood was collected into one or two 7-ml heparinized Vacutainer® tubes (BD Vacutainer, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Wanllin Lakes, New Jesey, USA) and prepared for analysis within 30 min of collection by centrifugation at 2000 g (15 min, 4 °C). Plasma samples were stored at −20 °C and shipped on dry ice to be assayed at PPD Development (Middleton, Wisconsin, USA) using a high-performance liquid chromatography system equipped with a triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer (LC/MS/MS). The samples were assayed for donepezil, 6-OH donepezil and sertraline concentrations. For all analyses, the lower limit of quantification of this system was 0.20 ng ml−1, and its dynamic range was 0.20–60.0 ng ml−1. Quality control samples analysed with each analytical run had coefficients of variation of ≤ 6.29% for donepezil, ≤ 8.65% for 6-OH donepezil and ≤ 12.9% for sertraline.

Pharmacokinetic assessments

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated, using noncompartmental methods, from the plasma donepezil or sertraline concentrations. The area under the curve from 0 to 24 h (AUC0–24 h) and AUC from 0 to the last time point, t, with a measurable concentration (AUC0–t), were calculated by linear trapezoidal approximation. The maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) and time taken to attain Cmax (tmax) were evaluated directly from plasma drug concentration data without interpolation. The terminal elimination rate constant (λz) was determined from linear least squares regression analysis of logarithmic plasma concentration data and the terminal elimination half-life (t½) was calculated as 0.693 λz−1. The AUC from 0 to infinity (AUC0–∞) and the average steady-state plasma concentration (Css) of donepezil (determined as AUC0–24 h,ss/24 h) were also derived.

Safety analysis

Safety was evaluated at the screening by complete physical examination, routine clinical laboratory tests (haematology, clinical chemistry and routine urinalysis), measurement of vital signs, 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and a urine drug screen. Screening safety assessments were repeated at baseline. All AEs reported spontaneously by subjects or elicited during the physical examination were documented throughout the study using a COSTART dictionary of preferred terms [24], with time of onset, time of cessation and assessment of severity and causality. Adverse events occurring after the initial dose of study medication were defined as treatment emergent. Additional safety assessments included routine physical examinations on days 0 and 22 (washout) of each dosing period, clinical laboratory tests on days 0, 2, 14, 16 and 22, and urine drug screens on day 14 of each dosing period. ECGs were performed at each study visit and vital signs were monitored on days 0, 1, 2, 14, 15, 16 and 22 of each study period.

Statistical analysis

A total of 12 subjects was considered sufficient to allow accurate characterization of the PK of each drug and to assess any significant drug–drug interactions between donepezil and sertraline. Arithmetic mean values of PK parameters for the combination treatment group (donepezil HCl + sertraline HCl) were compared with those for each of the individual treatment regimens on day 1 (single-dose assessment) and day 15 (steady state) of each dosing period.

Inter-group analyses were performed using analysis of variance (anova) for crossover design, incorporating subject, treatment sequence, subject (sequence), dosing period and treatment group as factors. All statistical tests were two-tailed and were performed at the 5% level of significance. Pharmacokinetic parameters were evaluated using the entire population of subjects completing the study and the safety analysis included all subjects who received at least one dose of the study medication.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

Sixteen men and three women aged 20–45 years (mean ± s.e., 31.3 ± 1.7) were enrolled in the study, of whom 10 subjects were Black, eight were White and one was Hispanic. Their mean weight was 76.6 ± 2.0 kg (range 57.0–89.8). Genotyping analysis confirmed that all subjects were extensive CYP 2D6 metabolizers. Sixteen subjects completed the study (all three dosing periods) and were included in the population for PK analysis. One of the subjects who completed all three dosing periods (and was included in the PK analysis) discontinued at the request of the investigator while he was repeating period 2 (donepezil HCl + sertraline HCl) due to an elevated eosinophil count (2.1 × upper limit of normal) that was considered possibly related to treatment. He was repeating this period because he took clarithromycin (a prohibited medication) for a respiratory tract infection during the initial period 2.

A further three subjects withdrew prematurely from the study and were not included in the PK analysis. One subject receiving donepezil HCl alone discontinued for personal reasons, and two male subjects discontinued due to AEs. Of these, one discontinued during treatment with donepezil HCl + sertraline HCl because of nausea/stomach cramps considered possibly related to treatment, and the other discontinued during treatment with sertraline HCl alone because of respiratory tract infection and cold symptoms that were considered not related to treatment.

Five subjects had previously taken OTC medications or dietary supplements, and 11 subjects took OTC medications during the study (mostly analgesic/anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics and/or cold medications for pain, headache, bruises or cold symptoms). In total, three subjects took concomitant OTC medications (analgesic and anti-inflammatory medications for pain and bruising or antibiotics for respiratory infections for reasons unrelated to study medication) that contravened protocol regulations; one patient received ibuprofen when blood samples were taken for PK analysis, one patient received amoxicillin and then guaifenesin, and the third patient (described above) received clarithromycin.

Pharmacokinetics

Donepezil.

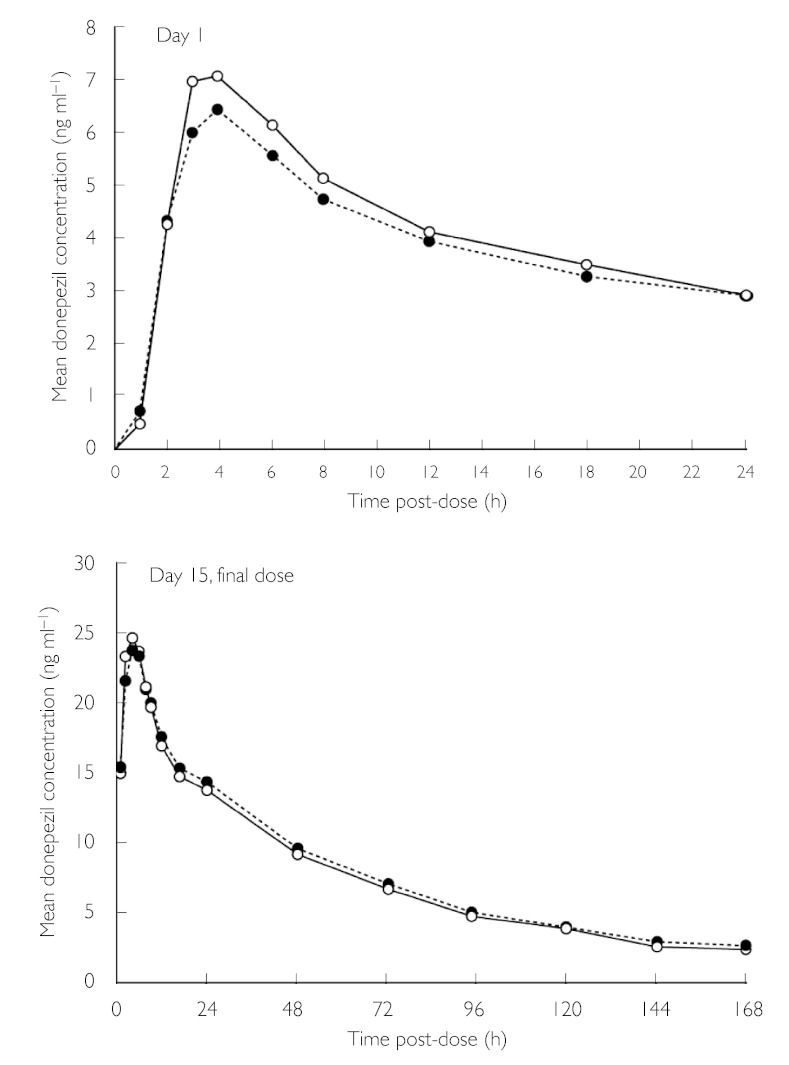

The concomitant administration of sertraline HCl with donepezil HCl was not associated with any significant differences in donepezil concentrations, tmax or AUC0–24 h values on day 1, compared with those observed with donepezil HCl alone (Figure 1, Table 2). A small (+11.3%) but significant (P = 0.02) difference in donepezil Cmax was observed on day 1. The administration of sertraline HCl with donepezil HCl did not significantly alter any of the steady-state values of donepezil PK parameters on day 15, compared with those observed with donepezil alone (Figure 1, Table 2).

Figure 1.

Mean plasma donepezil concentration over time at day 1 and after the last dose on day 15, during treatment with donepezil HCl alone and donepezil HCl + sertraline HCl. Donepezil HCI + sertraline HCI (n = 16) (○—○), donepezil HCI only (n = 16) (•---•)

Table 2.

Summary of donepezil pharmacokinetic parameters in each donepezil HCl treatment group on days 1 and 15

| Mean (s.e.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Donepezil HCl only (n = 16) | Donepezil HCl + sertraline HCl (n = 16) | Difference as a percentage |

| Day 1 | |||

| AUC0–24 h (ng·h ml−1) | 94.2 (3.3) | 100.3 (3.7) | +6.5 |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 6.7 (0.29) | 7.5 (0.26)* | +11.3 |

| tmax (h) | 3.9 (0.31) | 3.6 (0.20) | −7.9 |

| Day 15 | |||

| AUC0–24 h (ng·h ml−1) | 426.7 (25.3) | 420.0 (19.0) | −1.6 |

| AUC0–∞ (ng·h ml−1) | 1541 (152) | 1461 (104) | −5.2 |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 24.4 (1.3) | 25.4 (1.1) | +4.2 |

| tmax (h) | 3.1 (0.20) | 3.0 (0.18) | −2.0 |

| t1/2 (h) | 56.0 (2.4) | 54.9 (2.2) | −1.9 |

| Css (ng ml−1) | 17.78 (1.05) | 17.50 (0.79) | −1.6 |

P < 0.05 for donepezil HCl vs. donepezil HCl + sertraline HCl.

Sertraline.

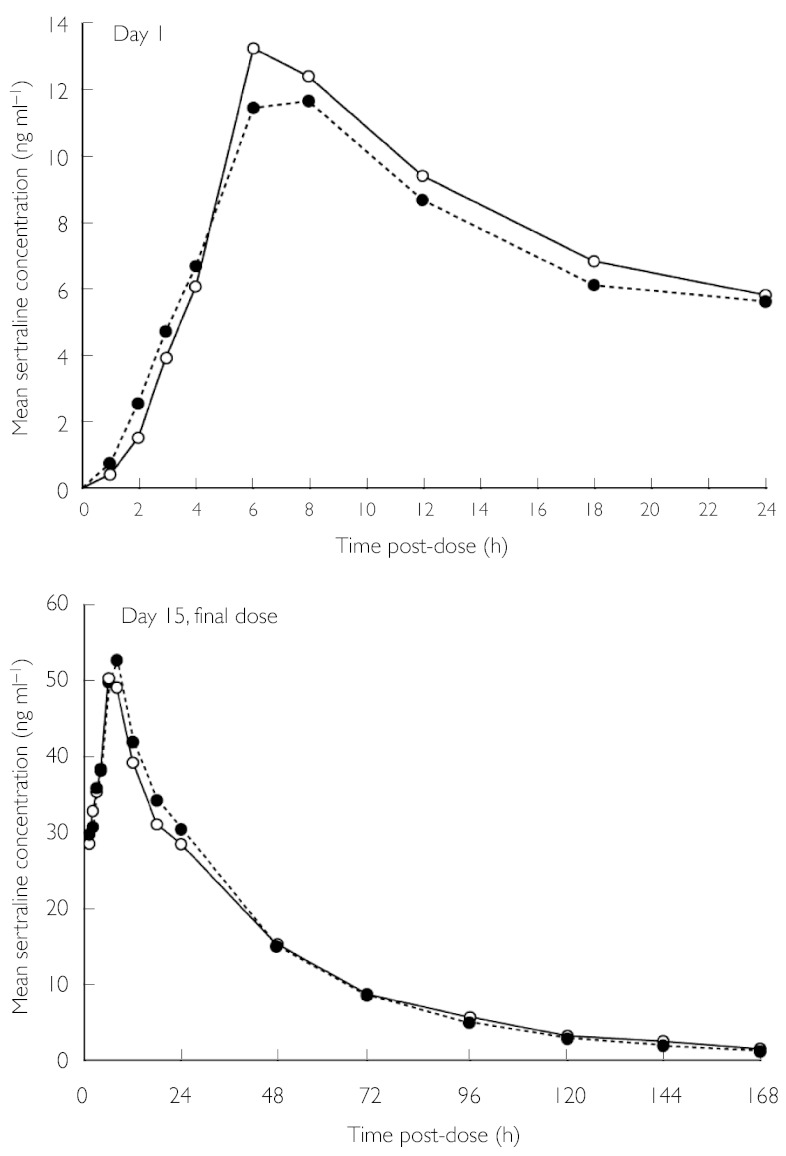

No statistically significant differences in sertraline PK were observed between the combination treatment and sertraline HCl only groups, on either day 1 or day 15 (Figure 2, Table 3).

Figure 2.

Mean plasma sertraline concentration over time at day 1 and after the last dose on day 15, during treatment with sertraline HCl alone and sertraline HCl + donepezil HCl. Donepezil HCI + sertraline HCI (n = 16) (○—○), sertraline HCI only (n = 16) (•---•)

Table 3.

Summary of sertraline pharmacokinetic parameters in each sertraline HCl treatment group on days 1 and 15

| Mean (s.e.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Sertraline HCl only (n = 16) | Donepezil HCl + sertraline HCl (n = 16) | Difference as a percentage |

| Day 1 | |||

| AUC0–24 h (ng·h ml−1) | 172.5 (20.9) | 183.8 (12.9) | +6.6 |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 12.1 (1.3) | 13.8 (0.98) | +14.1 |

| tmax (h) | 7.0 (0.26) | 6.8 (0.25) | −3.6 |

| Day 15 | |||

| AUC0–24 h (ng·h ml−1) | 934.0 (134.0) | 883.9 (145.0) | −5.4 |

| AUC0–∞ (ng·h ml−1) | 2167 (392) | 2192 (586) | +1.2 |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 55.1 (7.6) | 50.9 (7.6) | −7.6 |

| tmax (h) | 6.9 (0.26) | 6.6 (0.34) | −4.6 |

| t1/2 (h) | 27.5 (1.5) | 28.4 (2.1) | +3.5 |

| Css (ng ml−1) | 38.9 (5.6) | 36.8 (6.0) | −5.4 |

Tolerability.

Most AEs were of mild or moderate severity and short duration (1–3 days). The overall incidence of AEs (number of subjects reporting at least one AE) was 10/17 during treatment with donepezil HCl alone, 14/17 during treatment with sertraline HCl alone, and 16/18 during treatment with donepezil HCl + sertraline HCl (Table 4).

Table 4.

Incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) during treatment with donepezil HCl (5 mg) alone, sertraline HCl (50–100 mg) alone or donepezil HCl (5 mg) + sertraline HCl (50–100 mg) in combination

| Incidence, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Donepezil HCl only (n = 17) | Sertraline HCl only (n = 17) | Donepezil HCl + sertraline HCl (n = 18) | |

| Any AE* | 10 (59) | 14 (82) | 16 (89) |

| Body as a whole | 8 (47) | 12 (71) | 8 (44) |

| Asthenia | 1 (6) | 4 (24) | 3 (17) |

| Headache | 7 (41) | 6 (35) | 4 (22) |

| Digestive system | 4 (24) | 6 (35) | 14 (78) |

| Diarrhoea | 1 (6) | 5 (29) | 7 (39) |

| Nausea | 1 (6) | 2 (12) | 7 (39) |

| Musculoskeletal system | 2 (12) | 1 (6) | 1 (6) |

| Nervous system | 5 (29) | 6 (35) | 6 (33) |

| Respiratory system | 1 (6) | 4 (24) | 3 (17) |

| Urogenital system | 1 (6) | 5 (29) | 1 (6) |

Total number of subjects reporting ≥1 AE.

The incidence of individual AEs was generally low during treatment with donepezil HCl or sertraline HCl alone, for which headache was the most frequently reported AE (in 7/17 and 6/17 subjects, respectively) (Table 4). The most commonly occurring nervous system AE during donepezil treatment was dizziness (two subjects), while the most common nervous system AEs reported during sertraline treatment were insomnia (two subjects) and somnolence (two subjects). Abnormal ejaculation was reported by two subjects receiving only sertraline HCl.

The incidence of individual AEs was generally higher during treatment with donepezil HCl + sertraline HCl than with either drug alone, most notably in the case of digestive system AEs. However, none of the individual digestive system AEs was significantly more common during treatment with donepezil HCl + sertraline HCl compared with either medication alone.

Overall, AEs that were judged to be possibly or probably related to treatment included 22/42 events in subjects on donepezil HCl alone, 29/49 events in subjects on sertraline HCl alone and 44/66 events in subjects on donepezil HCl + sertraline HCl. No serious AEs were reported throughout the study and, with the exception of one patient who discontinued due to moderate eosinophilia, no clinically significant laboratory test abnormalities or changes in vital signs or ECG findings were observed during the study.

Discussion

The potential for drug–drug interactions is an important consideration in the treatment of AD, as patients are generally elderly and are usually taking concomitant medications for other co-morbid illnesses. Among the SSRIs, sertraline is known for its relatively low potential for PK interactions with other drugs [20, 26]. This is believed to be due partly to its efficacy at relatively low plasma levels and partly to its low potency as an inhibitor of CYP isoenzymes (compared with fluoxetine, paroxetine or their metabolites) [27–30], making it a suitable drug for the treatment of depression in AD patients. In addition, the PK of sertraline are linear over the clinically relevant dosing range and are similar in young and elderly healthy individuals [20, 21]. This study examined the possibility of drug–drug interactions when donepezil HCl (5 mg day−1 for 15 days) is co-administered with the antidepressant sertraline HCl (50 mg day−1 for 5 days, followed by 100 mg day−1 for 10 days) in healthy subjects.

In general, the PK parameters of donepezil in this study are consistent with previously published data [9]. Following multiple-dose co-administration with sertraline HCl, steady-state (day 15) PK parameters for donepezil were unaltered. The PK of donepezil were similarly unaffected after treatment with a single dose of sertraline HCl at the start of the study (day 1), except for Cmax which showed a small but statistically significant rise (11.3%) on day 1 compared with the Cmax when donepezil HCl was administered alone. However, in terms of the threshold value for changes in plasma drug concentrations that are considered clinically relevant by the US Food and Drug Administration (± 20%), this relatively small change in donepezil Cmax does not represent any clinically meaningful interaction after single dosing.

There is some overlap in the metabolic pathways involved in the breakdown of donepezil and sertraline. CYP 2D6 and CYP 3A4 are the isoenzymes primarily responsible for donepezil metabolism, accounting for metabolites comprising approximately 10% and 8%, respectively, of the administered dose of donepezil [10]. The relative contributions of these isoenzymes towards overall sertraline metabolism in vitro are 35% for CYP 2D6 and 9% for CYP 3A4 [31]. The effect of sertraline on plasma donepezil concentrations (Cmax) after single doses of donepezil HCl and sertraline HCl on day 1 in this study may therefore be partially attributable to the inhibition of CYP 2D6 [32].

It is not clear why the minor effect of sertraline on donepezil Cmax is only seen after a single dose and not after multiple dosing (steady state). Both donepezil and sertraline have a greater binding affinity for CYP 2D6 than for CYP 3A4. However, it is possible that that the main pathways by which donepezil and sertraline are metabolized diverge as the steady state is approached, due to the differential contributions of CYP 2D6 and CYP 3A4 to donepezil metabolism at different plasma drug concentrations [33]. Thus, at low plasma drug concentrations (such as those seen after single doses) both drugs may compete for binding to CYP 2D6, with sertraline having a slightly stronger affinity, whereas at the higher plasma drug concentrations observed under steady-state conditions, the primary route of elimination for donepezil is via CYP 3A4, and that for sertraline remains CYP 2D6.

The observed slight increase in donepezil Cmax during initial co-administration with sertraline HCl on day 1, coupled with a minimal or no increase in AUC0–24 h and no change in tmax, indicates a small increase in the extent (rather than the rate) of donepezil absorption. This is supported by the fact that co-administration of sertraline HCl also did not alter the rate of donepezil absorption at steady state, as shown by the tmax and t½ values on day 15. Increased donepezil absorption could arise due to a decrease in the extent of first-pass metabolism of donepezil. If this is the case, the fourfold accumulation of donepezil during multiple dosing might diminish the impact of small differences in the extent of absorption for the preceding dose. This may be a contributory mechanism (additional to CYP-mediated effects) toward the lack of significant interactions with sertraline under steady-state conditions.

Donepezil has consistently demonstrated a low potential to alter the PK of other drugs (digoxin, warfarin, cimetidine, ketoconazole, theophylline) [11, 12, 34–36]. The high inhibition constant (Ki) values for donepezil inhibition of CYP 3A4 and CYP 2D6 indicate a weak inhibition by donepezil of the isoenzymes involved in sertraline metabolism. Although a 14% increase in sertraline Cmax was observed with co-administration of a single dose of donepezil on day 1, this was not significant. Indeed, no significant differences in sertraline PK were observed in this study during the co-administration of either a single dose (day 1) or multiple doses (day 15) of donepezil HCl.

Generally, the concurrent administration of donepezil HCl and sertraline HCl was well tolerated, with no serious AEs reported during this study. This observation is consistent with clinical data from AD patients who received both donepezil HCl and sertraline HCl [37]. While over half of the AEs were considered possibly or probably related to study medication, most were mild and transient, resolving by completion of the study. In general, the AEs experienced by subjects receiving either donepezil HCl or sertraline HCl alone have been reported in previous clinical trials of each drug [4, 5, 38, 39], and could be predicted based on their modes of action. When receiving the combination treatment, the incidence of digestive system AEs appeared to be slightly increased relative to the individual drug treatments. However, there were no statistically significant differences in the incidence of any individual AE when the drugs were administered in combination, compared with those recorded during treatment with either drug alone. Thus, co-administration of donepezil HCl and sertraline HCl did not appear to produce any AEs not associated with individual drug treatment. However, this study was not powered to detect a difference in the incidence of AEs. No physical examination, vital sign or ECG abnormalities were associated with the combination of donepezil HCl and sertraline HCl.

In summary, no significant differences in either the PK or tolerability of donepezil HCl or sertraline HCl occurred during multiple-dose co-administration at steady-state. Since these two agents would be administered under steady-state conditions in the clinical setting, these results demonstrate that donepezil HCl and sertraline HCl can be co-prescribed safely, with no clinically meaningful PK interactions.

Acknowledgments

The analytical work for this study was performed at PPD Development, 8500 Research Way, Middleton, WI, USA.

References

- 1.Perry EK, Tomlinson BE, Blessed G, Bergman K, Gibson PH, Perry RH. Correlation of cholinergic abnormalities with senile plaques and mental test scores in senile dementia. BMJ. 1978;2:1457–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6150.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence AD, Sahakian BJ. Alzheimer disease, attention, and the cholinergic system. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1995;9(Suppl. 2):43–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ARICEPT®. Teaneck, NJ: Eisai Inc; 2000. (donepezil hydrochloride tablets) US package insert December. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers SL, Farlow MR, Doody RS, Mohs R, Friedhoff LT. A 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1998;50:136–44. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns A, Rossor M, Hecker J, Gauthier S, Petit H, Moller HJ, Rogers SL, Friedhoff LT. The effects of donepezil in Alzheimer's disease – results from a multinational trial. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10:237–44. doi: 10.1159/000017126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winblad B, Engedal K, Soininen H, Verhey F, Waldemar G, Wimo A, Wetterholm AL, Zhang R, Haglund A, Subbiah P Donepezil Nordic Study Group. A 1-year randomized, placebo-controlled study of donepezil in patients with mild to moderate AD. Neurology. 2001;57:489–95. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohs RC, Doody RS, Morris JC, Ieni JR, Rogers SL, Perdomo CA, Pratt RD, “312” Study Group A 1-year, placebo-controlled preservation of function survival study of donepezil in AD patients. Neurology. 2001;57:481–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers SL, Friedhoff LT. Pharmacokinetic and pharamacodynamic profile of donepezil HCl following single oral doses. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46(Suppl. 1):1–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.0460s1001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers SL, Cooper NM, Sukovaty R, Pederson JE, Lee JN, Friedhoff LT. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of donepezil HCl following multiple oral doses. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46(Suppl. 1):7–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.0460s1007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tiseo PJ, Perdomo CA, Friedhoff LT. Metabolism and elimination of 14C-donepezil in healthy volunteers: a single-dose study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46(Suppl. 1):19–24. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.0460s1019.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiseo PJ, Perdomo CA, Friedhoff LT. Concurrent administration of donepezil HCl and cimetidine: assessment of pharmacokinetic changes following single and multiple doses. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46(Suppl. 1):25–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.0460s1025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tiseo PJ, Perdomo CA, Friedhoff LT. Concurrent administration of donepezil HCl and ketoconazole: assessment of pharmacokinetic changes following single and multiple doses. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46(Suppl. 1):30–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.0460s1030.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy ML, Cummings JL, Fairbanks LA, Bravi D, Calvani M, Carta A. Longitudinal assessment of symptoms of depression, agitation, and psychosis in 181 patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1438–43. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.11.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Migliorelli R, Teson A, Sabe L, Petrachi M, Leiguarda R, Starkstein SE. Prevalence and correlates of dysthymia and major depression among patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:37–44. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teri L, Wagner A. Alzheimer's disease and depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:379–91. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McRae T, Orazem J. A large-scale, open-label trial of donepezil in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: side-effects and concomitant medication use. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;2(Suppl. 1):S176. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tariot PN, Cummings JL, Katz IR, Mintzer J, Perdomo CA, Schwam EM, Whalen E. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease in the nursing home setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1590–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyketsos CG, Sheppard JM, Steele CD, Kopunek S, Steinberg M, Baker AS, Brandt J, Rabins PV. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of sertraline in the treatment of depression complicating Alzheimer's disease: initial results from the depression in Alzheimer's disease study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1686–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McRae T, Griesing T, Whalen E. Managing behavioural symptoms in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(Suppl. 8):S109. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodnick PJ, Goldstein BJ. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in affective disorders – I. Basic Pharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12(Suppl. B):S5–S20. doi: 10.1177/0269881198012003021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warrington SJ. Clinical implications of the pharmacology of sertraline. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1991;6(Suppl. 2):11–2. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199112002-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Height and Weight Standards. New York: Metropolitan Life Insurance Company; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zoloft®. New York, NY: Pfizer Inc; 2002. (sertraline hydrochloride) tablets and oral concentrate. US package insert, May. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reimherr FW, Chouinard G, Cohn CK, Cole JO, Itil TM, LaPierre YD, Masco HL, Mendels J. Antidepressant efficacy of sertraline: a double-blind, placebo- and amitriptyline-controlled, multicenter comparison study in outpatients with major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51:18–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Food and Drug Administration. COSTART: Coding Symbol Thesaurus for Adverse Reaction Terms. 3. Rockville, MD: Center for Drugs and Biologics, Division of Drug and Biological Products Experience; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janicak PG, Davis JM, Preskorn SH, Ayd FJ., Jr . Principles and Practice of Psychopharmacotherapy. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crewe HK, Lennard MS, Tucker GT, Woods FR, Haddock RE. The effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) activity in human liver microsomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;34:262–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1992.tb04134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ball SE, Ahern D, Scatina J, Kao J. Venlafaxine: in vitro inhibition of CYP2D6 dependent imipramine and desipramine metabolism; comparative studies with selected SSRI, and effects on human CYP3A4, CYP2C9 and CYP1A2. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;43:619–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ, Duan SX, Harmatz J, Wright CE, Shader RI. Inhibition of terfenadine metabolism in vitro by azole antifungal agents and by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants: Relation to pharmacokinetic interactions in vivo. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;16:104–12. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199604000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ring BJ, Binkley SN, Roskos L, Wrighton SA. Effects of fluoxetine, norfluoxetine, sertraline and desmethylsertraline on human CYP3A catalyzed 1′hydroxymidazolam formation in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1131–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi K, Ishizuka T, Shimada N, Yoshimura Y, Kamijima K, Chiba K. Sertraline N-demethylation is catalyzed by multiple isoforms of human cytochrome P-450 in vitro. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:763–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sproule BA, Otton SV, Cheung SW, Zhong XH, Romach MK, Sellers EM. CYP2D6 inhibition in patients treated with sertraline. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17:102–6. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199704000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmider J, Greenblatt DJ, von Moltke LL, Shader RI. Relationship of in vitro data on drug metabolism to in vivo pharmacokinetics and drug interactions: implications for diazepam disposition in humans. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;16:267–72. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199608000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tiseo PJ, Perdomo CA, Friedhoff LT. Concurrent administration of donepezil HCl and digoxin: assessment of pharmacokinetic changes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46(Suppl. 1):40–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.0460s1040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tiseo PJ, Perdomo CA, Friedhoff LT. The effect of multiple doses of donepezil HCl on the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of warfarin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46(Suppl. 1):45–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.0460s1045.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tiseo PJ, Foley K, Friedhoff LT. Concurrent administration of donepezil HCl and theophylline: assessment of pharmacokinetic changes following multiple-dose administration in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;6(Suppl. 1):35–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.0460s1035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McRae T, Griesing T, Whalen E. Effectiveness of donepezil on behavioral disturbances in mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21(Suppl. 1):S93. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dewan MJ, Anand VS. Evaluating the tolerability of newer antidepressants. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187:96–101. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199902000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Finkel SI, Richter EM, Clary CM. Comparative efficacy and safety of sertraline versus nortriptyline in major depression in patients 70 and older. Int Psychogeriatr. 1999;11:85–9. doi: 10.1017/s104161029900561x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]