Abstract

Aims

To characterize the pharmacokinetics of fumarates in healthy subjects.

Methods

Ten subjects received a single fumarate tablet (containing 120 mg of dimethylfumarate and 95 mg of calcium-monoethylfumarate) in the fasted state and after a standardized breakfast in randomized order. Prior to and at fixed intervals after the dose, blood samples were drawn and the concentrations of monomethylfumarate, the biologically active metabolite, as well as dimethylfumarate and fumaric acid were measured using high-performance liquid chromatography.

Results

After a lag time, a transient increase in serum monomethylfumarate concentrations in the blood was observed, whereas dimethylfumarate and fumaric acid concentrations remained below the detection limit. The tlag was 240 min [range 60–603 min; 95% confidence interval (CI) 139, 471] shorter when the tablet was taken after an overnight fast (90 min; range 60–120 min; 95% CI 66, 107) than when taken with breakfast (300 min; range 180–723 min; 95% CI 0, 1002). The tmax was 241 min (range 60–1189 min, 95% CI 53, 781) shorter when the tablet was taken after an overnight fast (182 min; range 120–240 min; 95% CI 146, 211) than when taken with breakfast (361 min; range 240–1429 min; 95% CI 0, 1062). The mean Cmax for monomethylfumarate in the blood of fasting subjects was to 0.84 mg l−1 (range 0.37–1.29 mg l−1; 95% CI 0.52, 1.07) and did not differ from that in fed subjects (0.48 mg l−1; range 0–1.22 mg l−1; 95% CI 0, 5.55).

Conclusions

The pharmacokinetics of monomethylfumarate in healthy subjects after a single tablet of fumarate are highly variable, particularly after food intake. Further experiments exploring the pharmacokinetics of oral fumarates are warranted in order to elucidate the mechanisms underlying variability in reponse in patients.

Keywords: fumarates, high-performance liquid chromatography, monomethylfumarate, pharmacokinetics, psoriasis

Introduction

Psoriasis vulgaris is an autoimmune skin disease characterized by epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of inflammatory cells in affected lesions. Current long-term (anti-inflammatory) therapies for psoriasis cause serious adverse effects [1–5]. Fumaric acid is effective against psoriasis [6], but its main drawback is that it causes gastric ulcers. However, this adverse affect can be circumvented using mixtures of dimethylfumarate and monoethylfumarate in enteric-coated tablets [7–12]. There is some variability in the response to these fumarates among psoriasis patients. The reason for this is unknown and may involve both pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic factors. There are few data on the pharmacokinetics of fumarates in humans [13]. Animal studies indicate that fumarates are completely absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract within 2 h after administration and that dimethylfumarate is rapidly hydrolysed in the intestinal mucosa to monomethylfumarate. This bioactive intermediate is further metabolized into fumaric acid, which enters the citric acid cycle (personal communication, Joshi et al. Fumapharm AG, Switzerland). As a first step in understanding why patients with psoriasis vary in their response to fumarates we have characterized the pharmacokinetics of fumarates in healthy individuals following a single dose taken on an empty stomach as well as with a meal.

Materials and methods

The Medical Ethics Committee of Leiden University Medical Centre approved this open, randomized, cross-over study and all subjects gave written informed consent. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in compliance with International Conference on Harmonization/Good Clinical Practice regulations. The study population consisted of 10 healthy subjects (four male, six female) between 19 and 28 years with a normal weight for height (body mass index range 18–25 kg m−2).

Study protocol

The subjects participated on two study days. On one day a single tablet was taken after an overnight fast and on the other day the tablet was taken with a standardized breakfast (2060 kJ – 45% as protein, 12% as fat and 43% as carbohydrates). The tablets (Fumaraat 120®) containing 120 mg of dimethylfumarate and 95 mg of calcium-monoethylfumarate were purchased from Tiofarma (Oud-Beijerland, Netherlands). Each study day lasted 24 h and was separated from the other days by a wash-out period of at least 1 week.

Blood was collected shortly before and at fixed intervals after tablet dosing and placed in 4-ml tubes containing sodium fluoride and potassium oxalate as antioxidant and esterase inhibitors. Immediately after collection, the samples were vortexed, transferred onto ice for 5 min and centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 min at 1500 × g. The resulting supernatant was stored at −30 °C until analysis.

Analytical methods

The concentrations of the fumarates were determined as described by Litjens et al. (unpublished data). After precipitation of serum proteins with acetonitrile, dimethylfumarate was analysed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

The sample preparation for monomethylfumarate and fumaric acid required a protein precipitation step using metaphosphoric acid followed by extraction with diethylether and pH adjustment to pH 0.5. Sodium chloride was added before centrifugation at 12 000 × g. Thereafter, the ether layer was transferred to a glass vial and after evaporation the residue reconstituted in methanol: 0.1 m potassium phosphate buffer (KH2PO4/K2HPO4; pH 7.5) supplemented with 5 mm tetrabutylammonium dihydrogen phosphate 1 : 1 (v/v).

The HPLC instrument (Spectra SERIES P100) was equipped with an Alltima C18 column (5µ 5250 × 4.6 mm) and a precolumn. The mobile phase for dimethylfumarate was methanol : water 30 : 70 (v/v) and that for monomethylfumarate and fumaric acid was methanol : potassium phosphate buffer supplemented with 5 mm tetrabutylammonium dihydrogen phosphate 20 : 80 (v/v). The limit of detection for all three compounds was 0.01 mg l−1, the coefficients of variation for monomethylfumarate and dimethylfumarate were 7% and 9%at 0.5 mg l−1, respectively, and the recoveries of monomethylfumarate and dimethylfumarate were 75 ± 7% and 98 ± 3% (n = 6).

Data analysis

The pharmacokinetic parameters for monomethylfumarate were calculated by noncompartmental analysis using WinNonlin software (version 4; Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA, USA). Terminal half-life (t1/2) was estimated by log-linear regression of the terminal part of the concentration–time curve, where the number of points to be included was determined by the program. Lag-time (tlag), time at which peak concentrations of monomethylfumarate occurred (tmax), and peak concentrations of monomethylfumarate (Cmax) are reported for all subjects. Where possible, clearance/F (dose/AUC0–∞) was estimated. The nonparametric Friedman test was used to determine whether the descriptive pharmacokinetic parameters differed between the fed and fasting state.

Results

Two subjects withdrew consent after the first study day for personal reasons. The fumarate tablets were well tolerated by all participants, who suffered no serious adverse events. In addition, no abnormalities in haematology, blood biochemistry and urinalysis were observed. However, peripheral vasodilatation (mainly in the face and the upper part of the body) occurred after 10 (out of 18) of the doses and lasted between 1 and 3 h. This was not accompanied by a decrease in blood pressure, an increase in heart rate or by any other event.

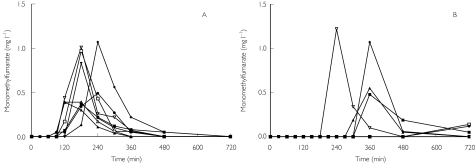

Concentrations of both dimethylfumarate and fumaric acid were below the detection limit. Serum monomethylfumarate concentrations vs. time profiles were similar in all eight subjects who took the drug after an overnight fast (Figure 1A), whereas subjects who were fed displayed either negligible monomethylfumarate concentrations or values similar to those in fasting subjects (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Concentration–time profiles for monomethylfumarate in the serum of eight healthy subjects after a single Fumaraat® tablet in the fasting (A) and fed (B) state

The main pharmacokinetic parameters for monomethylfumarate are summarized in Table 1. A transient increase in the serum concentration of monomethylfumarate (Figure 1A, B) occurred. The tlag and tmax in fasting subjects were 240 min shorter [range 60–602 min; mean ± SD 305 ± 179 min; 95% confidence interval (CI) 139, 471] and 241 min shorter (range 60–1189 min; mean ± SD 417 ± 394 min; 95% CI 53, 781), respectively (P = 0.008) than in fed subjects (Table 1). Moreover, the mean Cmax of monomethylfumarate in fasting individuals (n = 8) was 0.84 mg l−1 (range 0.37–1.29 mg l−1; mean ± SD 0.8 ± 0.33; 95% CI 0.52, 1.07), and did not differ from that in the fed subjects (0.48 mg l−1; range 0–1.22 mg l−1; mean ± SD 0.46 ± 0.47 mg l−1; 95% CI 0, 5.55) (Table 1). In four out of eight subjects who took the drug with a breakfast, very low concentrations of monomethylfumarate were observed.

Table 1. Serum pharmacokinetic parameters for monomethylfumarate in eight healthy subjects after a single Fumaraat 120® tablet in the fasting state and after a standardized breakfast.

| tlag (min) | tmax (min) | Cmax (mg l−1) | Cl/F (l min−1) | AUC0–∞ (mg × min l−1) | t1/2 (min) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Fasting | Fed | Fasting | Fed | Fasting | Fed | Fasting | Fed | Fasting | Fed | Fasting | Fed |

| 1 | 90 | 300 | 183 | 360 | 0.37 | 0.48 | 1.81 | 1.31 | 66 | 92 | 147 | 112 |

| 2 | 61 | 270 | 120 | 361 | 0.37 | 0.55 | 2.54 | 47 | 41 | |||

| 3 | 120 | 180 | 180 | 240 | 0.83 | 1.22 | 1.62 | 1.18 | 74 | 101 | 57 | 33 |

| 4 | 120 | 723 | 240 | 1429 | 1.07 | 0.09 | 0.91 | 133 | 54 | |||

| 5 | 90 | a | 152 | a | 1.29 | a | 0.85 | 142 | 38 | |||

| 6 | 60 | 300 | 221 | 360 | 0.85 | 1.07 | 1.42 | 84 | 26 | |||

| 7 | 90 | 481 | 183 | 722 | 0.97 | 0.12 | 1.31 | 91 | 40 | |||

| 8 | 60 | 483 | 148 | 725 | 0.59 | 0.14 | 1.86 | 64 | 48 | |||

| Median | 90 | 300 | 182 | 361 | 0.84 | 0.48 | 1.52 | 79 | 44 | |||

| Range | 60–120 | 180–723 | 120–240 | 240–1429 | 0.37–1.29 | 0–1.22 | 0.85–2.54 | 47–142 | 26–147 | |||

| Mean | 86 | 391 | 178 | 600 | 0.8 | 0.46 | 1.54 | 88 | 56 | |||

| SD | 25 | 184 | 39 | 412 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 33 | 37 | |||

| 95% CI | 66, 107 | 0, 1002 | 146, 211 | 0, 1062 | 0.52, 1.07 | 0, 5.55 | 1.08, 2.00 | 60–116 | 25–88 | |||

Owing to undetectable concentrations of monomethylfumarate, no values could be calculated.

Discussion

The main finding of the present study is that intake of a single oral dose of fumarate is followed by a transient rise in serum monomethylfumarate concentrations, whereas negligible concentrations of dimethylfumarate and fumaric acid are achieved. Furthermore, intake of the drug with breakfast decreased the extent of absorption and increased interindividual variability in serum monomethylfumarate concentrations. Therefore, dosing of fumarate to patients before meals should be advocated.

The present results are in agreement with our observation that dimethylfumarate is rapidly hydrolysed to monomethylfumarate at pH 8.5, but not in an acidic environment (Litjens et al., unpublished data). Assuming that uptake of fumarates occurs mainly in the small intestine, the hydrolysis of dimethylfumarate to monomethylfumarate in this compartment explains the negligible concentrations of dimethylfumarate in blood. Any dimethylfumarate not hydrolysed in the small intestine may be rapidly converted to monomethylfumarate in the circulation by esterases [14]. Further hydrolysis of this metabolite to fumaric acid occurs inside cells, thus fueling their citric acid cycle, as indicated by increased CO2 concentrations in the expired air of dogs injected with fumarates (personal communication, Joshi et al.).

Drug intake after breakfast resulted in an increased lag-time and the occurrence of variable peak concentrations of monomethylfumarate compared with the fasting state, a finding that is in agreement with those reported by Mrowietz et al.[13]. No definitive explanation for the differences in the pharmacokinetics of monomethylfumarate between fasting and fed subjects can be offered.

The present study is a first attempt to characterize the pharmacokinetics/dynamics of fumarates. Further experiments in healthy subjects as well as in psoriasis patients are warranted. It may be of importance to measure concentrations of monoethylfumarate since the combination of dimethylfumarate and monoethylfumarate resulted in a more rapid decrease in the clinical score for psoriasis than dimethylfumarate alone [15,16]. Another question to be answered is whether the rate and extent of appearance of monomethylfumarate in the blood determines the rate of response in psoriasis patients. This information may be useful in distinguishing patients who respond to fumarates from nonresponders.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by AstraZeneca R&D Charnwood, Loughborough, UK.

References

- 1.Kroesen S, Widmer AF, Tyndall A, Hasler P. Serious bacterial infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis under anti-TNF-alpha therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:617–21. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davison SC, Bunker CB, Basarab T. Etanercept for severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: observations on combination therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:831–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.495615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koo J, Lee J. Cyclosporine: what clinicians need to know. Dermatol Clin. 1995;13:897–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffiths CE, Clark CM, Chalmers RJ, Li Wan PA, Williams HC. A systematic review of treatments for severe psoriasis. Health Technol Assess. 2000;4:1–125. doi: 10.3310/hta4400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebwohl M. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2003;361:1197–204. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12954-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schweckendiek W. Heilung von Psoriasis vulgaris. Med Monatschr. 1959;13:103–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Altmeyer PJ, Matthes U, Pawlak F, et al. Antipsoriatic effect of fumaric acid derivates; results of a multicenter double-blind study in 100 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:977–81. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mrowietz U, Christophers E, Altmeyer P. Treatment of psoriasis with fumarates: results of a prospective multicentre study. German Multicentre Study. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:456–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nugteren-Huying WM, van der Schroeff JG, Hermans J, Suurmond D. Fumaric acid therapy for psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:311–12. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80766-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thio HB, van der Schroeff JG, Nugteren-Huying WM, Vermeer BJ. Long-term systemic therapy with dimethylfumarate and monoethylfumarate (Fumaderm®) in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1995;4:35–40. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoefnagel JJ, Thio HB, Willemze R, Bouwes Bavinck JN. Long-term safety aspects of systemic therapy with fumarates in severe psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:363–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litjens NHR, Nibbering PH, Barrois AJ, et al. Beneficial effects of fumarate therapy in psoriasis vulgaris patients coincide with downregulation of type-1 cytokines. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:444–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mrowietz U, Christophers E, Altmeyer P. Treatment of severe psoriasis with fumarates: scientific background and guidelines for therapeutic use. The German Fumaric Acid Ester Consensus Conference. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:424–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Werdenberg D, Joshi R, Wolffram S, Merkle HP, Langguth P. Presystemic metabolism and intestinal absorption of antipsoriatic fumarates. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2003;24:259–73. doi: 10.1002/bdd.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolbach DN, Nieboer C. Fumaric acid therapy in psoriasis: results and side effects of 2 years of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:769–71. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nieboer C, de Hoop D, Langendijk PN, Van Loenen AC, Gubbels J. Fumaric acid therapy in psoriasis: a double-blind comparison between fumaric acid compound therapy and monotherapy with dimethylfumaric acid ester. Dermatologica. 1990;181:33–7. doi: 10.1159/000247856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]