The paper by Grach et al. [1] in the Journal addresses the little explored potential benefit of combination opioids in analgesia. Compared with a published study documenting oxycodone-morphine synergy in rats [2], the antinociception study by Grach et al. in healthy subjects has significant design limitations to support their conclusions.

In rats, antinociception dose–response curves were produced for each of oxycodone and morphine for the relief of noxious thermal pain [2]. Baseline responses increased 3-fold and antinociceptive ED50 doses of oxycodone and morphine were 2.8 and 8.5 mg kg−1, respectively. These ED50 values agreed with previously published data [3]. Dose–response curves employing oxycodone:morphine combination at ratios of 3 : 1, 1 : 1 and 1 : 3 relative to the morphine or oxycodone ED50 alone, were constructed. Marked antinociceptive synergy was demonstrated using isobolographic analysis and validated by using selective antagonists for each of the combination components.

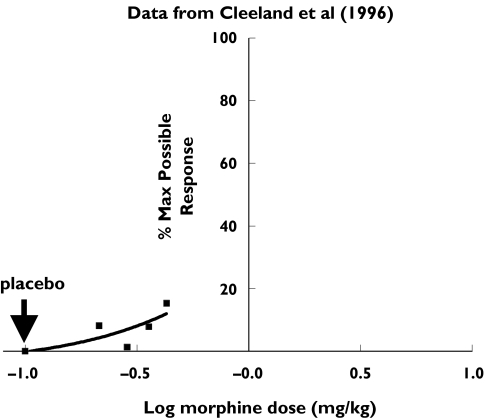

In their study, Grach et al. compared oral doses of 0.5 mg kg−1 morphine or 0.5 mg kg−1 oxycodone with 0.25 mg kg−1 morphine combined with 0.25 mg kg−1 oxycodone. The morphine dose selected was the lowest dose (0.43 mg kg−1) identified by Cleeland et al. [4] that produced significant antinociception in the cold pressor test. We have re-calculated the cold pressor tolerance (CPT) data as a percentage of the maximum possible response (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cold pressure Test Tolerance response data expressed as percentage of the maximum possible response (▪) show 0.25 mg kg−1 of morphine corresponds to the ED10

According to the Cleeland study [4], only the largest dose of oral morphine tested (0.43 mg kg−1) produced significant antinociception compared with the active diphenhydramine placebo. Thus the assumptions were that the Median Baseline response was 30 s and the Minimum acceptable dynamic range was three times the baseline response, similar to the rodent antinociception criteria. The Percentage Maximum Possible Effect (%MPE) was calculated as the percentage difference between the measured response and the baseline response, divided by the difference between the maximum response and the baseline response.

Figure 1 shows that 0.25 mg kg−1 morphine approximates the ED10. Using the same approach as Grach et al. (0.25 mg kg−1 morphine and oxycodone) represents, at best, the ED10 and ED25, respectively. Without additional dose–response data, it is not possible to confidently identify the effective doses of the individual opioids, the subantinociceptive dose range for cold pressor pain, or the doses needed to produce an adequate pharmacodynamic range in healthy subjects. Furthermore, their study highlights the poor sensitivity of this test for predicting clinically relevant doses of opioids as seen with morphine [4]. Thus, an alternative conclusion of this work is that the suitability of the cold pressor test to predict clinically relevant doses of opioids, administered alone or in combination, is questionable under the conditions of this study.

Lauretttiet al. in 2003[5] reported opioid synergy in chronic cancer-related pain. Briefly, 22 patients received controlled-release morphine (CRM) and controlled-release oxycodone (CRO) in a crossover design involving two sequential 14-day treatment periods with immediate-release morphine (IRM) available for breakthrough pain. The requirement for breakthrough IRM was 38% higher in patients receiving CRM than in patients receiving CRO, suggesting that a synergistic analgesic interaction took place when morphine was administered to patients receiving CRO.

In two double-blind, crossover studies involving 44 osteoarthritic patients with moderate to severe pain, the steady-state daily opioid requirements were approximately 40% less with morphine:oxycodone combinations compared with morphine alone (Smith et al. unpublished data). These findings suggest that morphine:oxycodone combinations produce greater than additive (and likely synergistic) pain relief in patients.

In summary, extrapolation of findings from an antinociception study in healthy subjects using single doses of opioids either individually or in combination, without prior adequate identification of the pharmacodynamic range for the pain being tested, needs reassessment. In order to be of predictive value, studies of antinociceptive synergy in healthy subjects need to be carefully designed, taking into consideration the full pharmacological range of the drugs being studied.

References

- 1.Grach M, Massalha W, Pud D, Adler R, Eisenberg E. Can coadministration of oxycodone and morphine produce analgesic synergy in humans? An experimental cold pain study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;58:235–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross FB, Wallis SC, Smith MT. Co-administration of sub-antinociceptive doses of oxycodone and morphine produces marked antinociceptive synergy with reduced CNS side-effects in rats. Pain. 2000;84:421–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00230-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pöyhiä R, Kalso EA. Antinociceptive effects and central nervous system depression caused by oxycodone and morphine in rats. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1992;70:125–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1992.tb00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleeland CS, Nakamura Y, Howland EW, Morgan NR, Edwards KR, Backonja M. Effects of oral morphine on cold pressor tolerance time and neuropsychological performance. Neuropsychopharm. 1996;15:252–62. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00205-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lauretti GR, Oliveira GM, Pereira NL. Comparison of sustained-release morphine with sustained-release oxycodone in advanced cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:2027–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]