Abstract

Aims

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the repeatability of forearm skin blood flow responses to intradermal injections of acetylcholine (ACh) and endothelin-1 (ET-1) using a double injection technique (DIT) and a laser Doppler imager (LDI) scanner in the human skin microcirculation.

Methods

We used a laser Doppler imager (Moor LDI V3.01) to continuously monitor the change in skin blood flow during intradermal administration of physiological saline (0.9% NaCl), acetylcholine (ACh 10−7, 10−8, 10−9 M) and endothelin-1 (ET-1 10−14, 10−16, 10−18 M) in 10 healthy male subjects. Subjects were examined on 3 different days for assessment of interday and interobserver repeatability. Injections of either drug were randomly placed on different sites of the forearm. Laser Doppler images were collected before and after injection at 2.5 min intervals for 30 min. Data were analysed after the completion of each experiment using Moor Software V.3.01. Results are expressed as changes from baseline in arbitrary perfusion units (PU).

Results

ACh caused a significant vasodilation (P< 0.0001 anova, mean ± SE: 766 ± 152 PU, ACh 10−9 M; 1868 ± 360 PU, ACh 10−8 M; 4188 ± 848 PU, ACh 10−7 M; mean of days 1 and 2, n = 10), and ET-1 induced a significant vasoconstrictive response (P< 0.0001 anova, −421 ± 83 PU, ET-1 10−18 M; −553 ± 66 PU, ET-1 10−16 M; −936 ± 90 PU, ET-1 10−14 M; mean of days 1 and 2, n = 10). There was no difference on the response to either drug on repeated days. Bland-Altman analyses showed a close agreement of responses between days with repeatability coefficients of 1625.4 PU for ACh, and 386.0 PU for ET-1 (95% CI: ACh, −1438 to 1747 PU, ET-1, −399 to 358 PU) and between observers with repeatability coefficients of 1057.2 PU for ACh and 255.8 PU for ET-1 (95% CI: ACh, −1024 to 1048 PU, ET-1, −252 to 249 PU). The variability between these responses was independent of average flux values for both ACh and ET-1. There was a significant correlation between responses measured in the same site, in the same individual on two different days by the same observer (ACh, r = 0.94, P < 0.0001; ET-1, r = 0.90, P < 0.0006), and between responses measured by two different observers (ACh, r = 0.94, P < 0.0001; ET-1, r = 0.91, P < 0.0003).

Conclusion

We have shown that interday and intraobserver responses to intradermal injections of ET-1 and ACh, assessed using the DIT in combination with an LDI scanner, exhibited good reproducibility and may be a useful tool for studying the skin microcirculation in vivo.

Keywords: Laser Doppler imager, microvascular, acetylcholine, endothelin-1

Introduction

The assessment of microvascular function is an important aspect in the process of evaluating the effect of drugs in vivo in humans. Conventional Doppler flowmetry is used for the continuous measurement of perfusion in real time at a single point on the skin. Interpretation of data obtained from a single point is, however, difficult due to the variability observed in skin perfusion [1]. More recently high-resolution laser Doppler imaging has been developed, which allows measurement over a large area without making contact with the skin, instead of a single point measurement [2]. In contrast to the flowmeter that uses an optical fibre to carry the laser beam to the skin, laser Doppler imaging is performed by a device that uses a moving mirror to direct the laser beam onto the skin. A region of the skin is scanned to give rise to a two-dimensional image of the movement of red blood cells in the area being scanned [2].

To date the application of laser Doppler imaging has proved useful in the assessment of burns [3–5], skin inflammation and vascular disorders [6–11]. Laser Doppler imaging has often been used for the assessment of changes in skin blood flow in response to acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside by iontophoresis, or to reactive hyperaemia [12–16], as well as in response to different vasoactive substances such as histamine, bradykinin, or endothelin applied using dermal microdialysis [17, 18]. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the repeatability of forearm skin blood flow responses to intradermal injections of acetylcholine (ACh) and endothelin-1 (ET-1) using the double injection technique (DIT) [19] in combination with a laser Doppler imager (LDI) scanner. We have previously reported the use of this injection method and laser Doppler flowmetry in health [20–22] and disease [23–25]. In the present study, we report for the first time an evaluation on the repeatability of responses to intradermal injection of ACh and endothelin-1 (ET-1), using the DIT and an LDI scanner, in the assessment of microvascular function in the human skin in vivo. We assessed the responses to these agents on the forearm skin microcirculation in a population of 10 young, healthy, nonsmoking male subjects.

Materials and Methods

Study population

The study population included 10 young, healthy, male subjects aged 24–34 years. All subjects were drug-free (had not taken any medication at least 10 days prior to the study day) and judged to be healthy on the basis of medical history, physical examination, and routine laboratory screening. The subjects were nonsmokers and had no history of hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, or diabetes. Investigations were carried out in the Department of Nephrology and Hypertension at the University of Essen, Germany and the subjects gave informed written consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Essen Medical School and was in accordance with the principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. The characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study population

| Subjects (n = 10) | Mean ± SEM | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.4 ± 1.0 | 24–34 |

| Height (cm) | 183.6 ± 1.7 | 171–191 |

| Weight (kg) | 77.1 ± 2.5 | 60–89 |

| Heart rate (min−1) | 60.7 ± 2.5 | 52–76 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 116.9 ± 4.2 | 98–138 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 61.8 ± 1.8 | 54–75 |

| Cholesterol (mg ml−1) | 168.1 ± 8.5 | 130–190 |

| Resting blood glucose (mg dl−1) | 83.0 ± 2.7 | 70–99 |

Laser Doppler imaging

A laser Doppler imager scanner (Moor LDI, Moor Instruments Ltd, Axminster, Devon, UK) was used to measure skin perfusion. The principle of operation of the LDI is as follows [1, 2, 26, 27]. A low power 633-nm-wavelength laser beam is directed onto an area of the skin by a computer-controlled mirror. The beam scans an area of skin determined by the distance between the mirror and the skin, and by the angle of the mirror. The laser beam penetrates the tissue and part of the incident light is scattered by moving red blood cells, causing a frequency broadening that is then detected by a photodetector. Red blood cell velocities and concentration give rise to the Doppler frequency shifts and account for the strength of the signal. The Doppler shift is thus proportional to a blood flow-related variable and is expressed in arbitrary perfusion units (PU). The data are collected by a computer and are visualized as a two-dimensional colour-coded image representing varying degrees of blood flow over the scanned area. The mean blood flow is computed to yield an average of pixels in a region of interest within the scanned area with the software provided by the manufacturer (Moor LDI 3.01, Moor Instruments Ltd, Axminster, Devon, UK).

The responses to the injection of ACh and ET-1 were scanned over the forearm. The size of the scanned area was determined individually. One picture took approximately 2 min using a scan resolution of 4 ms per pixel.

Study protocol

Experiments were performed on three study days, at least 7 days apart. The subjects and investigator were blinded to the drugs injected. Measurements were performed in a quiet, temperature-controlled (24 °C) room. On the study day, subjects reported to the laboratory in the fasting state. During the investigation subjects remained in the supine position. On each day 10 µl injections of ACh (10−9, 10−8, 10−7 M), ET-1 (10−18, 10−16, 10−14 M), or saline were given intradermally using a 27 gauge needle. Injections were made at random and into four sites per forearm. Arms were randomly chosen for the application of drug, and were supported by an inflatable cushion to avoid movement during the measurements. Drugs were injected into sites that exluded visible veins. Each site was marked with ink and documented by a photographic image so that the same site could be used on different days.

Subjects rested for a period of 30 min and then the forearm was scanned to assess resting skin blood flow. Skin temperature was 31 ± 0.3 °C. After this measurement, injections were administered. A double injection model was used as previously described [20]. This technique allows intradermal injection of two substances, such as an agonist and antagonist, into the same area of the skin to investigate their effects and interactions. In this study, saline and ET-1 or ACh were injected into the same site. Four double injections were administered in each arm. First, NaCl was injected into each of the four sites. Injections had to produce a symmetrical weal without visible spreading outside the weal, otherwise the injection site was excluded. A second injection containing ACh or ET-1 was then administered into three of these sites, while a fourth site received a second injection of NaCl and was used as control. All four injection sites were imaged concurrently. The LDI device was set for repetitive scanning and images were recorded after injection of drug at 2.5 min intervals during stimulation. Twelve images were collected during a period of approximately 30 min. The same protocol was repeated on the other arm.

Data and statistical analysis

Data from the laser Doppler imager scanner were analysed offline at the completion of each experiment using Moor Software V.3.01. Pixels were measured within a region of interest (ROI), which was a rectangle with an area of 2.5 cm2. For the assessment of interobserver variability, images were analysed by two different observers. Flux values corresponding to background were obtained from the image taken before injection and were subtracted from all measurements obtained after injection. Flux values were expressed as changes from baseline. In order to remove any effect of vehicle, flux values were calculated from double injections with NaCl and these values were then subtracted from the vasodilation or vasoconstriction induced by ACh and ET-1, respectively. The overall response for each concentration of drug over the 30 min stimulation period was calculated from the area under the curve (AUC).

Forearm skin blood flow was analysed by repeated-measures analysis of variance (anova). The repeatability of blood flow responses to ACh and ET-1 between two different study days and between two different observers was examined using the method of Bland and Altman [28]. Briefly, the difference in responses between two study days was plotted vs. the mean of the responses. Repeatability coefficients were calculated according to the recommendations of the British Standards Institution [28]. Simple linear regression analysis (Pearson) was applied to detect correlations between mean AUC values obtained in different days and by different observers. The strength of correlation was quantified by the correlation coefficients of simple (r) regression analysis. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant. All values have been expressed as mean ± SEM. Stastistical analysis was performed with Prism V4.0 for MS Windows (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego CA, USA).

Drugs

Endothelin-1 and acetylcholine were obtained from Clinalfa (Darmstadt, Germany). Saline (0.9% NaCl) was provided by the Hospital Pharmacy, University of Essen (Essen, Germany). Solutions of ET-1 (10−18, 10−16, 10−14 M) and ACh (10−9, 10−8, 10−7 M) were prepared immediately before use to avoid loss of efficacy using saline to dilute the drugs to a given concentration [20].

Results

All 10 subjects completed the study. There were no significant intrasubject differences between baseline measurements on each of the study days. Mean baseline values for all subjects for each day were: 1944 ± 285 PU (day 1), 1763 ± 260 PU (day 2), and 2060 ± 263 PU (day 3).

Forearm skin blood flow

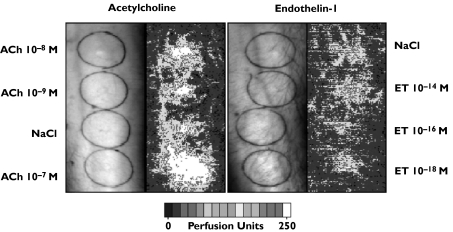

Laser Doppler images were recorded after intradermal injection of ACh (10−9, 10−8, 10−7 M) and ET-1 (10−18, 10−16, 10−14 M). Responses obtained 2 min after injection are shown for ACh and ET-1 in Figure 1. The colour scale illustrates increasing flux in arbitrary perfusion units. At the injection site, ACh markedly increased blood flow for all three concentrations. ACh did not induce a flare reaction. In contrast, ET-1 10−14 M induced marked vasoconstriction at the injection site, and vasodilatation in the surrounding area, the area of axon reaction (at a distance of 8 mm from the injection site) as previously described [21]. The other concentrations of ET-1 appeared to have only a mild vasoconstricting effect.

Figure 1.

Laser Doppler images recorded 2 min after intradermal injection of ACh (10−9, 10−8, 10−7 M) and ET-1 (10−18, 10−16, 10−14 M) on the forearm of a young healthy male volunteer are shown. The colour scale illustrates increasing flux in arbitrary perfusion units. At the injection site, ACh markedly increased blood flow for all three concentrations. ACh did not induce a flare reaction. In contrast, ET-1 induced vasoconstriction. A distinct weal and flare response was observed for ET-1 10−14 M

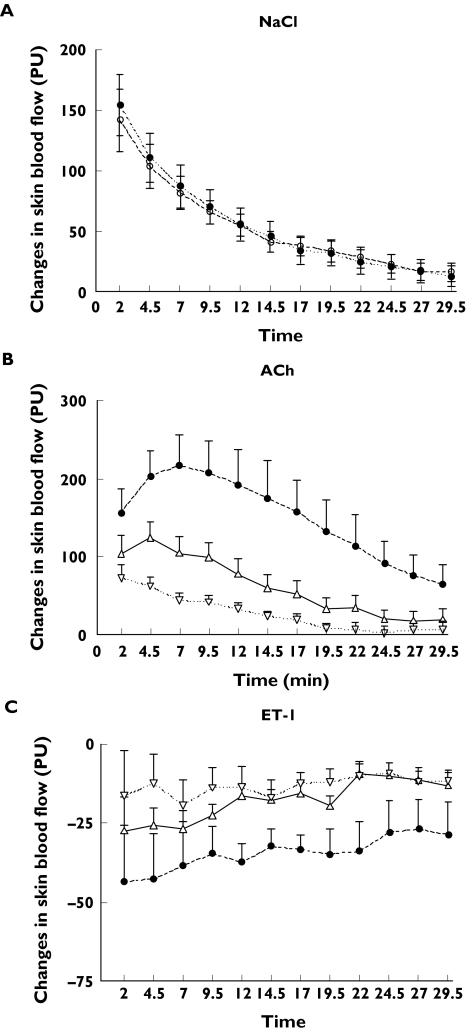

Time response curves and interday variability

Figure 2 shows the time-response curve obtained after injection with saline, ACh, or ET-1 for 12 time intervals assessed with the LDI scanner during a 30-min period. Skin blood flow is expressed in arbitrary perfusion units. In Figure 2A responses for saline are plotted for data obtained on two different days by the same observer in the same location of the left arm for all subjects. Values from the right arm were similar (data not shown). There was no difference in the vasodilatory effect of saline between day 1 and day 2. Changes in skin blood flow (PU) in response to ACh (10−9, 10−8, 10−7 M) and ET-1 (10−18, 10−16, 10−14 M) are shown in Figure 2B and 2C, respectively. For ACh and ET-1 responses correspond to images collected in day 1 and were similar to those obtained in day 2 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Changes in skin blood flow in arbitrary perfusion units (PU) are shown as a function of time for 12 time intervals assessed with the LDI scanner during a 30-min period. (A) Changes in skin blood flow in response to 0.9% NaCl. Responses to saline were measured on the forearm of left and right arms on two different days to assess interday variability. Measurements of blood flow were obtained after injection of NaCl, and subsequently at 2.5 min intervals for a period of 30 min. The responses shown correspond to those measured in the left arm, and were nearly identical to those of the right arm (data not shown). There was no difference between values obtained in day 1 (filled circles) or day 2 (empty circles). Day 1 (•), day 2 (○). (B) Changes in skin blood flow (PU) in response to ACh (10−9, 10−8, 10−7 M). ACh-10−7 (•), ACh-10−8 (▵), ACh-10−9 (▿). (C) Changes in skin blood flow (PU) in response to ET-1 (10−18, 10−16, 10−14 M). ET-1 10−14 (•), ET-1 10−16 (▵), ET-1 10−18 (▿). For ACh and ET-1 responses correspond to images collected in day 1 and were similar to those obtained in day 2 (data not shown). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM.

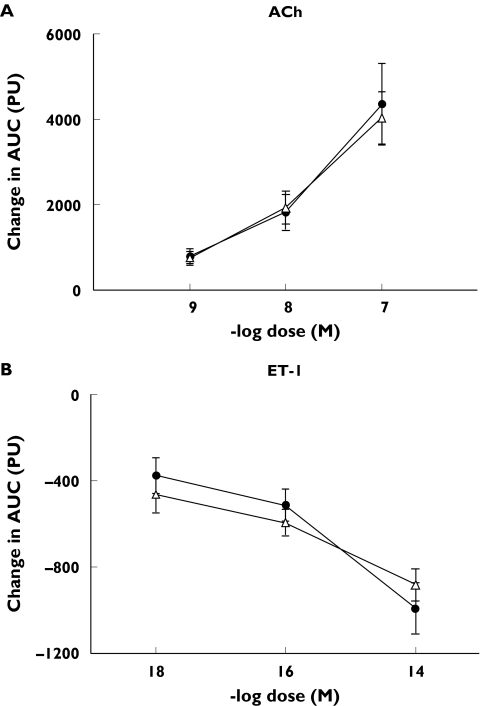

The areas under the curve generated on two different days after injection with three different concentrations of ACh or ET-1 are shown in Figure 3A and 3B, respectively. ACh significantly increased blood flow in a dose-dependent manner (P< 0.0001 vs. saline), whereas ET-1 induced a dose-dependent vasoconstrictive response (P< 0.0001 vs. saline). The responses were similar on both days for both drugs.

Figure 3.

Changes in the area under the curve (AUC), after injection with ACh (A) or ET-1 (B). Injections of ACh caused marked vasodilation, while ET-1 resulted in vasoconstriction, in a dose-dependent manner. There was no difference between measurements performed on two different days. Day 1 (•), day 2 (△)

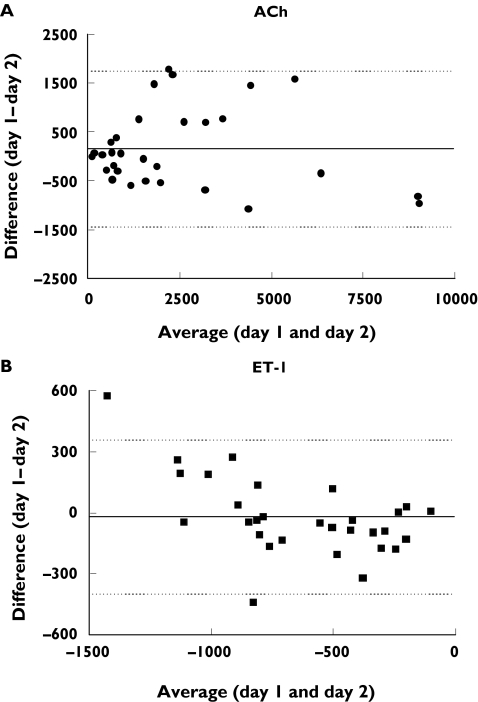

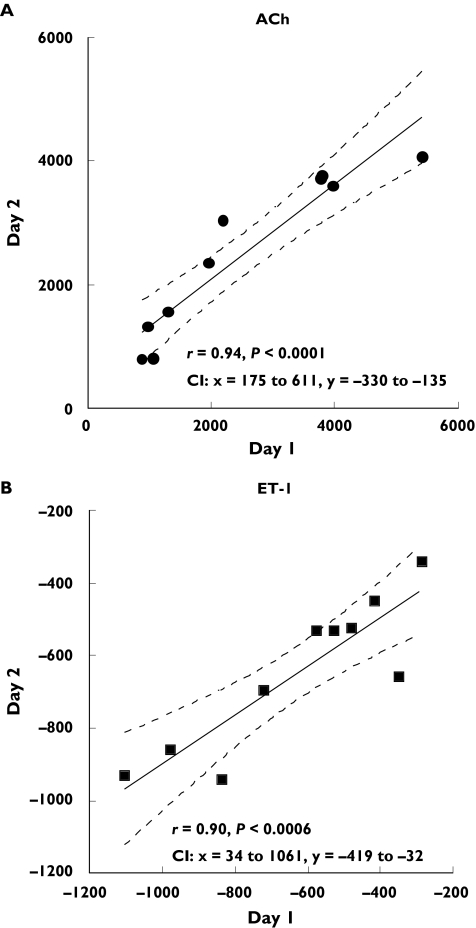

Repeatability of responses between two different days using Bland–Altman analysis are shown in Figure 4. The difference of responses between study day 1 and day 2 is plotted as a function of the average of responses of both days, for ACh (Figure 4A) and ET-1 (Figure 4B). The repeatability coefficients were 1625.4 PU for ACh, and 386.0 PU for ET-1 (95% CI −1438 to 1747 PU, ACh; −399 to 358 PU, ET-1). This analysis also ascertained that the variability in the responses was not dependent on the magnitude of the flux. The flux values ranged between 100 to approximately 9000 PU for ACh, and between−100 to −2000 PU for ET-1. Coefficients of variation for interday variability were: 0.15 ± 0.04 (ACh10−7), 0.20 ± 0.04 (ACh10−8), 0.17 ± 0.03 (ACh10−9), and 0.11 ± 0.02 (ET-1 10−14), 0.13 ± 0.03 (ET-1 10−16), 0.15 ± 0.05 (ET-1 10−18). Figure 5 shows that there was a significant correlation between measurements of ACh (r= 0.94, P < 0.0001) and ET-1 obtained on two different days (r= 0.90, P < 0.0006) by the same observer (n = 10).

Figure 4.

Bland–Altman plots for assessment of interday repeatability. The difference in responses measured on the same site on two different days is plotted vs. the average of the responses for ACh (A) and ET-1 (B). Each response is the change from baseline in skin blood flow, expressed in arbitrary perfusion units. The solid line corresponds to the mean of the differences. The dotted lines indicate the limits of agreement defined as the mean difference ± SD

Figure 5.

Correlations between measurements of skin blood flow obtained in the same site of the arm, on two different days in 10 subjects are shown for ACh (A) and ET-1 (B). There was a significant relationship between day 1 and day 2 in response to ACh (r= 0.94, P < 0.0001) and ET-1 (r= 0.90, P < 0.0006). Dotted lines show 95% confidence intervals (CI)

Inter observer variability

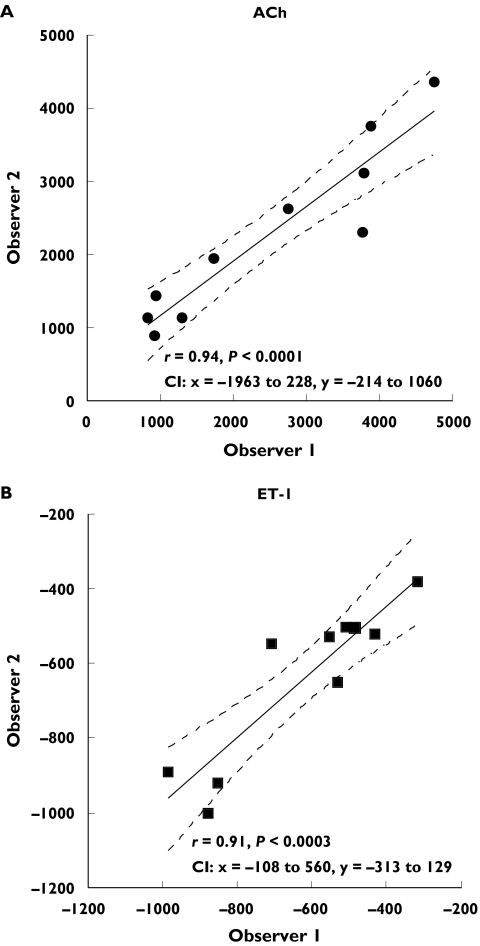

Bland–Altman plots to evaluate repeatability of responses to ACh and ET-1 between two different observers are shown in Figure 6A and 6B, respectively. The repeatability coefficients were 1057.2 PU for ACh and 255.8 PU for ET-1 (95% confidence intervals: −1024 to 1048 PU, ACh; −252–249 PU, ET-1). For both ACh and ET-1 the variability of responses between observers was consistent as the average increased. Coefficients of variation for interobserver variability were: 0.17 ± 0.04 (ACh10−7), 0.15 ± 0.04 (ACh10−8), 0.21 ± 0.03 (ACh10−9), and 0.12 ± 0.02 (ET-1 10−14), 0.11 ± 0.03 (ET-1 10−16), 0.17 ± 0.03 (ET-1 10−18). There was a significant correlation between measurements performed by two different observers for both ACh (Figure 7A, r = 0.94, P < 0.0001) and ET-1 (Figure 7B, r = 0.91, P < 0.0003) for all subjects studied.

Figure 6.

Bland–Altman plots for interobserver variability. The difference in responses measured on the same site, by two different observers, is plotted vs. the average of the responses for ACh (A) and ET-1 (B). The solid line is the mean of the differences, and the dotted lines show the limits of agreement

Figure 7.

Correlations between measurements of skin blood flow performed on the same site, by two different observers are shown. There was a significant correlation between measurements performed by two different observers for both ACh (A, r = 0.94, P < 0.0001) and ET-1 (B, r = 0.91, P < 0.0003). Dotted lines show 95% confidence intervals (CI)

Discussion

In this study we evaluated the repeatability of forearm skin blood flow responses noninvasively using a double injection technique in combination with a laser Doppler imager scanner. We evaluated the repeatability of responses to intradermal injections of acetylcholine and endothelin-1 in a population of young, healthy, nonsmoking male subjects. Our major finding is that responses to ET-1 and ACh measured between two different days and between different observers exhibited good reproducibility.

Laser Doppler imaging technology has often been used to assess the response of skin blood flow to the transdermal application of acetylcholine by iontophoresis [12–15]. In these studies day-to-day coefficients of variation ranged from about 10%[14], to 23%[12] for ACh. Our results for ACh are consistent with these reports as our coefficients of variation ranged between 15 and 21%. These values were higher than those reported by Kubli et al. possibly due to the influence of site to site variation. Although the same site was studied in each subject between different days, the injection site was randomly selected during the first visit in a proximal or distal area of the arm. Kubli et al. reported a site to site variation of approximately 20%. The repeatability of skin forearm vasoconstricton to ET-1 was lower, with coefficients of variation ranging between 11 and 17%, consistent with values reported using venous occlusion plethysmography [29]. However, comparisons between studies are difficult due to differences in study populations, methods of drug application, and the precise conditions utilized in the investigations.

Repeated measures performed between two different days and between two different observers, and analysed using the method of Bland and Altman, showed that most of the differences were within 95% confidence intervals. The largest variability in response to ACh appeared to occur with higher concentrations (ACh 10−7 M and ACh 10−8 M) possibly due to the various effects described for this drug, namely stimulation and release of vasodilators nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclins [30], stimulation and release of vasoconstrictor prostanoids from the endothelium [31], inhibition of noradrenaline from nerves [32], and stimulation of the local axon reflex [33]. Interestingly, the values obtained using different concentrations of endothelin exhibited a more uniform distribution and demonstrate the ability of the LDI combined with the DIT to detect a reduction in blood flux. For both ACh and ET-1 interday and interobserver data exhibited highly significant correlation coefficients.

We have introduced the double injection technique and have previously performed minimal invasive in vivo pharmacology in humans using laser Doppler flowmetry [19–24,34]. This technique allows the investigator to inject two substances or drugs into the same site, and evaluate their effects and interactions. Thus an agonist can be injected simultaneously with an antagonist. A major advantage of the DIT is its low invasiveness such that very low doses of a drug can be injected into the skin and several sites can be studied in the same individual on the same study day. In this way we were able to assess the vasodilatory and vasoconstrictive effects of different doses of ACh and ET-1, respectively, by studying dose–response curves concurrently.

In this study we used the DIT in combination with a laser Doppler imaging scanner which allows the measurement of skin perfusion over a large area, containing a large number of points that are adjacent to each other on the skin [35]. Due to the variability in skin perfusion [36], and the heterogeneous spatial distribution of the responses to sodium chloride, ACh and ET-1, perfusion values obtained by the LDI are likely to be more accurate than conventional laser Doppler flowmetry (which measures only a spot typically 1 mm in diameter). Furthermore, laser Doppler imaging is noninvasive, there is no contact with the skin, and therefore induces no pressure artefacts during imaging. Our results using the laser Doppler imaging scanner extend our previous findings on the effects of endothelin in experimental clinical studies using laser Doppler flowmetry, and provide new information on the assessment of acetylcholine using this technique.

In summary, this is the first study evaluating repeatability of responses to intradermal injection of acetylcholine and endothelin-1 using the double injection technique and assessed using an LDI scanner in a population of young, healthy, nonsmoking male subjects. Our results suggest that the combined use of these techniques may be a useful tool for in vivo pharmacology.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) WE 1772/3–2,3–3, and a grant from the OERTEL Foundation.

References

- 1.Nilsson GE, Tenland T, Oberg PA. Evaluation of a laser Doppler flowmeter for measurement of tissue blood flow. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1980;27(10):597–604. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1980.326582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Essex TJ, Byrne PO. A laser Doppler scanner for imaging blood flow in skin. J Biomed Eng. 1991;13(3):189–94. doi: 10.1016/0141-5425(91)90125-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niazi ZB, Essex TJ, Papini R, Scott D, McLean NR, Black MJ. New laser Doppler scanner, a valuable adjunct in burn depth assessment. Burns. 1993;19(6):485–9. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(93)90004-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Droog EJ, Steenbergen W, Sjoberg F. Measurement of depth of burns by laser Doppler perfusion imaging. Burns. 2001;27(6):561–8. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(01)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pape SA, Skouras CA, Byrne PO. An audit of the use of laser Doppler imaging (LDI) in the assessment of burns of intermediate depth. Burns. 2001;27(3):233–9. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(00)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Church MK, Clough GF. Scanning laser Doppler imaging and dermal microdialysis in the investigation of skin inflammation. Allergy Clin Immunol Int. 1997;113(2):41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Speight EL, Farr PM. Erythemal and therapeutic response of psoriasis to PUVA using high-dose UVA. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131(5):667–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb04980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krogstad AL, Lonnroth P, Larson G, Wallin BG. Capsaicin treatment induces histamine release and perfusion changes in psoriatic skin. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141(1):87–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahluwalia P, McGill JI, Church MK. Nedocromil sodium inhibits histamine-induced itch and flare in human skin. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132(3):613–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Economides PA, Caselli A, Tiani E, Khaodhiar L, Horton ES, Veves A. The effects of atorvastatin on endothelial function in diabetic patients and subjects at risk for type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(2):740–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson ME, Moore TL, Lunt M, Herrick AL. Digital iontophoresis of vasoactive substances as measured by laser Doppler imaging – a non-invasive technique by which to measure microvascular dysfunction in Raynaud's phenomenon. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43(8):986–91. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris SJ, Shore AC. Skin blood flow responses to the iontophoresis of acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside in man: possible mechanisms. J Physiol. 1996;496(2):531–42. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veves A, Akbari CM, Primavera J, Donaghue VM, Zacharoulis D, Chrzan JS, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthetase in diabetic neuropathy, vascular disease, and foot ulceration. Diabetes. 1998;47(3):457–63. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubli S, Waeber B, Dalle-Ave A, Feihl F. Reproducibility of laser Doppler imaging of skin blood flow as a tool to assess endothelial function. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2000;36(5):640–8. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200011000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newton DJ, Khan F, Belch JJ. Assessment of microvascular endothelial function in human skin. Clin Sci (Lond) 2001;101(6):567–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan F, Newton DJ, Smyth EC, Belch JJ. The influence of vehicle resistance on transdermal iontophoretic delivery of acetylcholine and sodium nitroprusside in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2004. pp. 883–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Clough GF, Bennett AR, Church MK. Effects of H1 antagonists on the cutaneous vascular response to histamine and bradykinin: a study using scanning laser Doppler imaging. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138(5):806–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katugampola R, Church MK, Clough GF. The neurogenic vasodilator response to endothelin-1: a study in human skin in vivo. Exp Physiol. 2000;85(6):839–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wenzel RR. Minimal invasive in vivo pharmacology: news of a new method holding promise in nephrology-related research. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12(4):649–51. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.4.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wenzel RR, Noll G, Luscher TF. Endothelin receptor antagonists inhibit endothelin in human skin microcirculation. Hypertension. 1994;23(5):581–6. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wenzel RR, Zbinden S, Noll G, Meier B, Luscher TF. Endothelin-1 induces vasodilation in human skin by nociceptor fibres and release of nitric oxide. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;45(5):441–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wenzel RR, Ruthemann J, Bruck H, Schafers RF, Michel MC, Philipp T. Endothelin-A receptor antagonist inhibits angiotensin II and noradrenaline in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52(2):151–7. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01422.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wenzel RR, Duthiers N, Noll G, Bucher J, Kaufmann U, Luscher TF. Endothelin and calcium antagonists in the skin microcirculation of patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1996;94(3):316–22. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wenzel RR, Bruck H, Baumgart D, Oldenburg O, Erbel R, Philipp T. Skin microcirculation in healthy subjects and patients with arteriosclerosis. Herz. 1999;24(7):576–80. doi: 10.1007/BF03044229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wenzel RR, Siffert W, Bruck H, Philipp T, Schafers RF. Enhanced vasoconstriction to endothelin-1, angiotensin II and noradrenaline in carriers of the GNB3 825T allele in the skin microcirculation. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12(6):489–95. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200208000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riva C, Ross B, Benedek GB. Laser Doppler measurements of blood flow in capillary tubes and retinal arteries. Invest Ophthalmol. 1972;11(11):936–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stern MD. In vivo evaluation of microcirculation by coherent light scattering. Nature. 1975;254(5495):56–8. doi: 10.1038/254056a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strachan FE, Newby DE, Sciberras DG, McCrea JB, Goldberg MR, Webb DJ. Repeatability of local forearm vasoconstriction to endothelin-1 measured by venous occlusion plethysmography. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54(4):386–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubanyi GM. Endothelium-derived relaxing and contracting factors. J Cell Biochem. 1991;46(1):27–36. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240460106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tesfamariam B, Jakubowski JA, Cohen RA. Contraction of diabetic rabbit aorta caused by endothelium-derived PGH2-TxA2. Am J Physiol. 1989;257(5 Part 2):H1327–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.5.H1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Rourke ST, Vanhoutte PM. Adrenergic and cholinergic regulation of bronchial vascular tone. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146(5 Part 2):S11–4. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.5_Pt_2.S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walmsley D, Wiles PG. Assessment of the neurogenic flare response as a measure of nociceptor C fibre function. J Med Eng Technol. 1990;14(5):194–6. doi: 10.3109/03091909009009960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenzel RR, Czyborra P, Luscher T, Philipp T. Endothelin in cardiovascular control: the role of endothelin antagonists. Curr Hypertens Rep. 1999;1(1):79–87. doi: 10.1007/s11906-999-0077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wardell K, Jakobsson A, Nilsson GE. Laser Doppler perfusion imaging by dynamic light scattering. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1993;40(4):309–16. doi: 10.1109/10.222322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tenland T, Salerud EG, Nilsson GE, Oberg PA. Spatial and temporal variations in human skin blood flow. Int J Microcirc Clin Exp. 1983;2(2):81–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]