Abstract

Aims

Rosiglitazone, a thiazolidinedione antidiabetic medication used in the treatment of Type 2 diabetes mellitus, is predominantly metabolized by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme CYP2C8. The anti-infective drug trimethoprim has been shown in vitro to be a selective inhibitor of CYP2C8. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of trimethoprim on the CYP2C8 mediated metabolism of rosiglitazone in vivo and in vitro.

Methods

The effect of trimethoprim on the metabolism of rosiglitazone in vitro was assessed in pooled human liver microsomes. The effect in vivo was determined by evaluating rosiglitazone pharmacokinetics in the presence and absence of trimethoprim. Eight healthy subjects (four men and four women) completed a randomized, cross-over study. Subjects received single dose rosiglitazone (8 mg) in the presence and absence of trimethoprim 200 mg given twice daily for 5 days.

Results

Trimethoprim inhibited rosiglitazone metabolism both in vitro and in vivo. Inhibition of rosiglitazone para-hydroxylation by trimethoprim in vitro was found to be competitive with apparent Ki and IC50 values of 29 µm and 54.5 µm, respectively. In the presence of trimethoprim, rosiglitazone plasma AUC was increased by 31% (P = 0.01) from 2774 ± 645 µg l−1 h to 3643 ± 1051 µg l−1 h (95% confidence interval (Cl) for difference 189, 1549), and half-life was increased by 27% (P = 0.006) from 3.3 ± 0.5 to 4.2 ± 0.8 h (95% Cl for difference 0.36, 1.5). Trimethoprim reduced the para-O-sulphate rosiglitazone/rosiglitazone and the N-desmethylrosiglitazone/rosiglitazone AUC(0–24) ratios by 22% and 38%, respectively.

Conclusions

These results indicate that trimethoprim is a competitive inhibitor of CYP2C8-mediated rosiglitazone metabolism in vitro and that trimethoprim administration increases plasma rosiglitazone concentrations in healthy subjects.

Keywords: rosiglitazone, trimethoprim, CYP2C8, drug interaction

Introduction

The significance of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C8 to drug elimination is expanding due to its relative distribution, polymorphic expression, and the rapidly increasing knowledge of its role in drug metabolism. CYP2C8 is primarily distributed in the liver [1], and it is the second most abundant member of the CYP2C family expressed in this organ [2]. CYP2C8 is also found in the lung [3], kidney, adrenal gland, mammary gland, brain, uterus, and ovary tissue [1]. CYP2C8 is polymorphically expressed with five allelic variants identified to date, CYP2C8*2 (Ile269Phe), CYP2C8*3 (Arg139Lys, Lys399Arg) [4], CYP2C8*4 (Ile264Met) [5], and CYP2C8*5 (frame shift mutation) [6]. Altered in vitro activity has been demonstrated for the CYP2C8*2 and CYP2C8*3 variant alleles [4–6]. The CYP2C8*2 allele is found mainly in African-Americans, has a frequency of 0.18, and is associated with decreased affinity for paclitaxel and a two-fold lower intrinsic clearance of 6α-hydroxypaclitaxel (due to a two-fold higher apparent Km with no change in Vmax). The CYP2C8*3 allele has a frequency of 0.13, is found primarily in Caucasians, and is associated with decreased paclitaxel turnover [4]. These genetic polymorphisms may play a role in the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic response to drugs metabolized by CYP2C8, which includes paclitaxel [7], amodiaquine [8], repaglinide [9], morphine [10], and rosiglitazone [11–13]. In addition, CYP2C8 metabolizes retinoic acid [14] and arachidonic acid [4, 15] and so may have an important physiological role.

Rosiglitazone is a thiazolidinedione antihyperglycemic agent used in the treatment of type 2 diabetes [11, 12]. Thiazolidinediones exert their clinical effects via the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), which facilitates the expression of genes responsible for glucose and lipid metabolism [16]. Rosiglitazone undergoes extensive metabolism with essentially no parent drug excreted unchanged in the urine [12]. Rosiglitazone is primarily metabolized by CYP2C8, with CYP2C9 contributing to a minor extent [11]. The two major metabolites of rosiglitazone produced by CYP2C8 are para-hydroxyrosiglitazone and N-desmethylrosiglitazone [11, 13], which account for >80% of all metabolic products isolated in human plasma after rosiglitazone administration [12]. The sulphate conjugate of para-hydroxyrosiglitazone, para-O-sulphate-rosiglitazone is the major plasma metabolite [12]. Based on these characteristics, conversion of rosiglitazone to para-O-sulphate-rosiglitazone may be a useful index of CYP2C8 activity.

It has been suggested that one means by which an enzyme-selective probe drug can be validated is to evaluate its pharmacokinetics in subjects who are treated with an inhibitor of the target enzyme [17]. The nonspecific CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 inhibitor gemfibrozil has been shown to adversely affect the pharmacokinetics of rosiglitazone causing a 2.3-fold increase in the area under the concentration-time curve [18]. The effect of a selective CYP2C8 inhibitor on rosiglitazone pharmacokinetics has not been evaluated. The antibiotic trimethoprim, which is commonly used in the treatment of respiratory and urinary tract infections, has been shown in vitro to selectively inhibit CYP2C8 at concentrations ranging from 5 to 100 µm (Ki = 32 µm) [19]. Trimethoprim administered at a dose of 200 mg twice daily achieves peak plasma concentrations of approximately 20 µm[20]. Based on the liver/plasma concentration ratio of 6.5–1 observed in monkeys [21], it has been proposed that this plasma concentration would produce approximate hepatic concentrations of 130 µm, which would yield greater than 80% inhibition of CYP2C8 [19, 20]. Trimethoprim was recently shown to inhibit the metabolism of the CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 substrate repaglinide, causing a 61% increase in the area under the curve [22]. The effect of trimethoprim administration on the CYP2C8-mediated metabolism of rosiglitazone has not been determined. Therefore, the purpose of these studies was to evaluate the in vitro and in vivo inhibitory effect of trimethoprim on the metabolism of this drug.

Methods

Clinical study

Human subjects

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh. Eight healthy nonsmoking subjects (four men and four women) provided written informed consent prior to the study. Subjects were determined to be healthy on the basis of past medical history, a physical examination and routine clinical laboratory tests. Subjects were excluded if they had any evidence of abnormal renal or hepatic function, had a BMI > 31 kg m−2, had preexisting medical conditions, or used any medications other than oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy. Women of child bearing age were tested for pregnancy prior to enrolment and on admission to each study phase for exclusionary purposes. Subject age, weight, and body mass index were 28.3 ± 11.9 years (21–57), 72.2 ± 16.6 kg (50.9–101), and 23.6 ± 3.0 kg m−2 (19.5–28.0), respectively (Mean ± SD (range)). Seven subjects were Caucasian and one was African-American. One of the female subjects was taking oral contraceptives and none of the subjects took complementary medicine or over-the-counter medications during the study visits.

Study design

The study had a randomized cross-over design in which subjects received: (1) rosiglitazone 8 mg and (2) rosiglitazone 8 mg and trimethoprim 200 mg twice daily for 5 days. Study visits were separated by a washout period of 1 week. Subjects abstained from alcohol and caffeine containing foods and beverages for 24 h, and from grapefruit or grapefruit juice and over-the-counter medications for 48 h prior to each study visit. After an overnight fast, subjects were administered rosiglitazone 8 mg (Avandia®, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) with 240 ml water at approximately 08.00 h. Subjects fasted for approximately 2 h after rosiglitazone dosing. Blood samples (10 ml) were obtained before and 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, 20, and 24 h after drug administration. In the other phase of the study, trimethoprim (200 mg) was administered for five days at approximately 07.30 h and 19.30 h. Rosiglitazone was administered at approximately 08.00 h on the fourth day of trimethoprim dosing. Blood samples were obtained as above with additional samples collected at 13 h prior to and 30, 36, and 48 h after rosiglitazone administration. Blood samples were drawn in EDTA tubes, kept on ice, and centrifuged within two hours of collection at 2500 g, 4 °C, for 15 min. Plasma was harvested and stored at −70 °C until analysis.

Drug and metabolite analysis

Rosiglitazone

Concentrations of rosiglitazone were determined as described previously [23]. Briefly, the internal standard, betaxolol (250 ng), was added to plasma (200 µl), and proteins were precipitated with 600 µL acetonitrile. Analysis was performed by HPLC with fluorescence detection. Rosiglitazone was monitored at an excitation wavelength (λex) of 247 nm and an emission wavelength (λem) of 367 nm and betaxolol was monitored at a λex of 235 nm and a λem of 310 nm. Separation was achieved with an Alltima Phenyl 5µm 250 mm × 4.6 mm column (Alltech Associates Inc., Deerfield, IL, USA), and an isocratic mobile phase of 10 m m sodium acetate (pH 5): acetonitrile (60 : 40) delivered at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. Intra- and interday precision ranged from 3.1 to 8.5% and from 2.3 to 5.7%, respectively.

Rosiglitazone metabolites

Plasma (100 µl) was added to 96-well 0.45µ Captiva® filter plates (Varian Inc, Lake Forest, CA, USA) preloaded with 300 µl of acetonitrile. The plates were vortex-mixed for 30 s, inverted for 5 min, and filtered under a vacuum. Water (300 µl) was added to the filtrate, and plates were briefly vortex-mixed. Aliquots (10 µl) were injected onto a Surveyor HPLC system connected to a TSQ Quantum MS/MS system (Thermo, Woburn, MA, USA). Chromatographic separation was performed using a Symmetry C8 5 µm, 2.1 × 150 mm column (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of (A) 0.1% formic acid in water and (B) 0.1% formic acid in methanol delivered at a flow rate of 200 µl min−1. Gradient elution was achieved with mobile phase that started at 80% A, ramped to 40% A over 2 min, changed to 10% A from 2.5 to 6.0 min, and then ramped back to 80% A over the next 0.2 min. Conditions were held at 80 : 20 for 1.3 min for a total run time of 8.5 min. Detection was achieved with positive electrospray ionization and data output was captured with Xcalibur® software (Thermo, San Jose, CA, USA). Precursor and product ions [M + H]+ detected were m/z 358.2/135, 374.2/151, and 344.2/121, for rosiglitazone, para-O-sulphate-rosiglitazone, and N-desmethylrosiglitazone, respectively [12, 13]. Since the sulphate group is lost in the mass spectrometer source, the mass detected is that of the para-hydroxy metabolite. The internal standard was detected with single ion monitoring [M + H]+ at 308.3. Metabolite concentrations were calculated in arbitrary units (U l−1) relative to the maximum peak concentration (Cmax) determined from the chromatographic output.

Trimethoprim

Concentrations of trimethoprim were determined as previously reported [24]. Briefly, the internal standard sulfamethazine (500 ng) was added to plasma (200 µl) and proteins were precipitated with perchloric acid (25 µl). Samples were vortex-mixed and then centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to injector vials and an aliquot (75 µl) was injected onto the HPLC system. Separation was achieved using a Synergi® 4 µm Polar-RP 150 mm × 4.6 mm column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) heated to 30 °C. The mobile phase, which consisted of ammonium formate (pH 3.0; 50 m m)-acetonitrile-methanol (90 : 6 : 4, v/v/v), was delivered isocratically at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. Detection was at an ultraviolet wavelength of 280 nm. Intra- and interday precision ranged from 1.1 to 1.7% and from 1.9 to 2.7%, respectively.

Determination of CYP2C8 genotype

Pyrosequencing assays were developed to genotype the CYP2C8*2, CYP2C8*3, and CYP2C8*4 alleles. PCR reaction mixtures (25 µl) consisted of 12.5 µl HotStarTaq® Master Mix (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), 1.5 µl DMSO, PCR primers (10 pmol each), 7 µl of water, and 40 ng DNA. PCR Primer sequences are shown in Table 1. PCR conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 15 min, 40 cycles consisting of (1) denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s (2) annealing at 56 °C (58 °C for Exon 8) for 30 s, and (3) extension at 72 °C for 45 s, followed by final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. Genotyping was performed using manufacturer protocol (Biotage AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Briefly, PCR products (10 µl) were immobilized with streptavidin-coated Sepharose beads and incubated. Beads were isolated and treated with 70% ethanol, denaturation buffer, and wash buffer. Beads were released into a mixture of annealing buffer and 10 pmol sequencing primer (Table 1), heated at 80 °C for 2 min and cooled to room temperature [25, 26]. Genotyping analysis was carried out using a PSQ HS 96 System (Biotage AB, Uppsala, Sweden) and data was captured with PSQ HS 96 SNP software (Biotage AB, Uppsala, Sweden).

Table 1.

PCR primers and sequencing primers for CYP2C8*2, CYP2C8*3, and CYP2C8*4

| Exon | PCR primers | Sequencing primers |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | F: B-5′-GTGTTCTCCCAGTTTCTGCCC-3′ | 5′-CGGTCCTCATGCTC-3′ |

| R: 5′-GACGCAGAGTAGAGTCACCCAC-3′ | ||

| 5 | F: B-5′-CAGGCTTGGTGTAAGATACATA-3′ | 5′-CTTACCTGCTCCATTTTGA-3′ |

| R: 5′-CAGAAGGATTCGATGAATCA CAA-3′ | ||

| 8 | F: 5′-CTCCTCACTTCTGGACTTCTTTA-3′ | 5′-CGTGCTACATGATGACA-3′ |

| R: B-5′-CCTTTAAATACAAATGGAAACGAG-3′ |

F: Forward; R: Reverse; B: Biotin labelled.

Data analysis

The rosiglitazone concentration-time data were analysed by noncompartmental methods. The terminal elimination rate constant (λz) was estimated by linear least squares regression analysis of the terminal portion of the log concentration-time data. Apparent elimination half-life was calculated from the expression 0.693 λz−1. The area under the concentration time curve (AUC) was determined using the linear trapezoidal rule with extrapolation to infinity. The apparent oral volume of distribution (Vd/F) was calculated from the expression Dose (λz × AUC)−1. The maximum concentration (Cmax) was determined from the experimental data. Tmax was the time at which Cmax was observed. For both rosiglitazone metabolites, the area under the concentration time curve (AUC) was calculated by the linear trapezoidal rule from 0 to 24 h. Pharmacokinetic calculations were performed using WinNonlin 2.1 (Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA, USA).

The trimethoprim concentration-time data were analysed by noncompartmental methods. The AUC was calculated for the 48-h period (four 12-h dosing intervals) after rosiglitazone administration by the linear trapezoidal rule. The maximum steady state concentration (Cssmax) and the minimum steady state concentration (Cssmin) were those observed over all four dosing intervals. The average steady state concentration (Cssave) was calculated by dividing the AUC(0–48) of trimethoprim by the total time (48 h). All calculations were performed with WinNonlin 2.1 (Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA, USA).

Rosiglitazone pharmacokinetic parameters were log-transformed where appropriate and compared by paired t-test unless specified otherwise. Confidence intervals (95%) on mean differences were calculated. Tmax was compared using the Wilcoxon matched pairs test. A two-sided P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant and all calculations were performed using PRISM software version 4.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Microsomal inhibition studies

Human liver microsomes

Pooled human liver microsomes (n = 29 donors) were purchased from BD Biosciences Discovery Labware (Bedford, MA, USA), who state that collection and processing of human tissue was conducted in compliance with all current regulatory and ethical requirements. Rosiglitazone was obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and gemfibrozil was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other reagents were of analytical grade or higher.

Incubation conditions

Metabolite formation was linear with respect to time (r2 > 0.98) and protein concentration (r2 > 0.97). Optimal incubation conditions were 0.2 mg microsomal protein (0.8 mg ml−1) incubated for 10 min at 37.0 °C. Incubations were performed in duplicate and consisted of 1.3 m m NADP+, 3.3 m m glucose-6-phosphate, 0.2 U glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 3.3 m m magnesium chloride, and 0.2 mg of microsomal protein in 250 µl phosphate buffer pH = 7.4. Incubations were started by addition of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 400 µl of ice cold acetonitrile and samples were vortexed immediately, and centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 g. Supernatant (75 µl) was injected onto the column and analysed as described above. The ratio of para-hydroxyrosiglitazone peak area to rosiglitazone peak area was used as a marker of CYP2C8 activity. The Km for the reaction was determined using substrate concentrations of 0, 5, 10, 25, 50, 75 and 100 µm.

Inhibition experiments

To determine IC50, rosiglitazone (10 µm) was incubated in the presence of trimethoprim (0, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 µm) and gemfibrozil (0, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 250 µm). To determine Ki, rosiglitazone was added to the microsomal suspension at varying concentration (5, 10, 25, 50 µm) in the presence of trimethoprim (0, 25, 50, 100 µm) and gemfibrozil (0, 25, 50, 100, 250 µm). Enzyme activity was plotted against nominal rosiglitazone concentration and the apparent Km was determined by fitting the Michaelis-Menten model to the untransformed data using nonlinear regression. The IC50 and apparent inhibitory constant (Ki) values were determined by nonlinear regression using PRISM software version 4.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Different models of enzyme inhibition (i.e. competitive, noncompetitive, uncompetitive, and mixed-type inhibition) were fitted to the data and the best fit was determined by analysis of the residuals, the standard error and the 95% confidence interval of the parameter estimates, and the Akaike' information criterion.

Results

Rosiglitazone was well-tolerated and no adverse events were noted when the drug was given alone. One of the eight subjects developed a rash 2 days after completing trimethoprim therapy. The rash resolved without therapeutic intervention within two days.

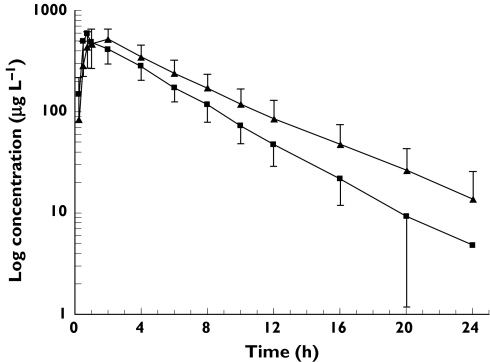

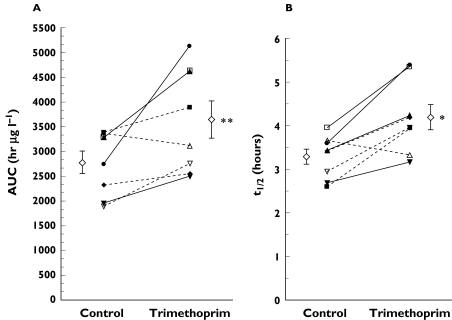

Mean log concentration vs. time profiles of eight subjects administered rosiglitazone in the presence and absence of trimethoprim are shown in Figure 1. Trimethoprim administration increased rosiglitazone AUC by 31% (P = 0.01) and t1/2 by 27% (P = 0.006), but had no effect on Cmax, tmax, and Vd/F (Table 2, Figure 2). There were no differences in para-O-sulphate-rosiglitazone or N-desmethylrosiglitazone AUC (Table 2), but the ratio of metabolite AUC to rosiglitazone AUC was decreased by 22% for para-O-sulphate-rosiglitazone (P = 0.02) and by 38% for N-desmethylrosiglitazone (P = 0.004). Trimethoprim administration decreased N-desmethylrosiglitazone Cmax by 22% (P = 0.02) but did not significantly affect para-O-sulphate-rosiglitazone Cmax (P = 0.19).

Figure 1.

Mean (±SD) log concentration vs. time profile of rosiglitazone in the presence (closed triangles) and absence (closed squares) of trimethoprim, 200 mg given twice daily for five days. Data are from eight healthy subjects. Control (▪), trimethoprim (▴)

Table 2.

Mean pharmacokinetic parameters for rosiglitazone and metabolites in the presence and absence of trimethoprim, 200 mg given twice daily for five days to eight healthy subjects

| Parameter | Control | Trimethoprim | Mean difference betweencontrol and trimethoprim(Cl 95%) | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosiglitazone | ||||||||

| AUC (µg l−1 h) | 2774 ± 645 | 3643 ± 1051 | 869 (189, 1549) | 0.01 | ||||

| Cmax (µg l−1) | 674.3 ± 235.4 | 591.9 ± 62.2 | −82.4 (−265.4, 100.7) | 0.32 | ||||

| Tmax (h) | 0.75 (0.5–4.0) | 0.88 (0.5–2.0) | 0.58 | |||||

| t1 /2 (h) | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.8 | 0.9 (0.36, 1.5) | 0.006 | ||||

| Vd/F (l) | 14.9 ± 3.1 | 14.1 ± 2.9 | −0.8 (−2.4, 0.75) | 0.26 | ||||

| Para-O-sulphate-rosiglitazone | ||||||||

| AUC (U l−1 h) | 14.9 ± 3.0 | 14.2 ± 3.3 | −0.61 (−2.4, 1.2) | 0.45 | ||||

| AUC ratio(POS: rosiglitazone) | 5.5 ± 1.1 | 4.3 ± 1.7 | −1.2 (−2.2, −0.3) | 0.02 | ||||

| N-desmethylrosiglitazone | ||||||||

| AUC (U l−1 h) | 15.6 ± 2.4 | 13.1 ± 4.8 | −2.5 (−5.9, 1.0) | 0.14 | ||||

| AUC ratio | 6.0 ± 1.7 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | −2.2 (−3.5, −1.0) | 0.004 | ||||

(NDR: ROSIGLITAZONE); POS: para-O-sulphaterosiglitazone; NDR: N-desmethylrosiglitazone.

Figure 2.

Rosiglitazone (A) AUC and (B) t1/2 in the presence (Trimethoprim) and absence (Control) of trimethoprim, 200 mg given twice daily for five days to eight healthy subjects. Solid lines indicate the wild type genotype (CYP2C8*1/*1) and dotted lines indicate the heterozygous genotype (CYP2C8*1/*2 or CYP2C8*1/*3)

Subjects were genotyped as CYP2C8*1/*1 (n = 4), CYP2C8*1/*2 (n = 1) and CYP2C8*1/*3 (n = 3). Genotype did not appear to affect rosiglitazone metabolism, as there were no significant differences between subjects with heterozygous and homozygous wild type genotypes (data not shown). However, there was a trend for the fold increase in rosiglitazone AUC to be greater in wild type subjects vs. subjects carrying an allelic variant (1.49 ± 0.26 vs. 1.16 ± 0.22, P = 0.1; data not shown).

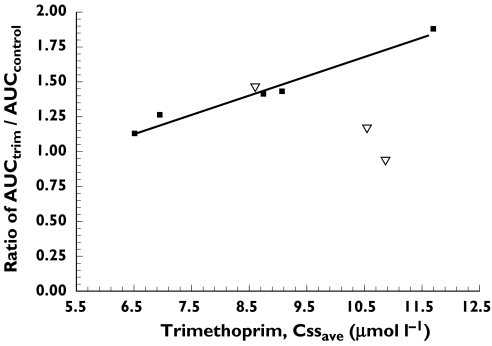

Trimethoprim reached steady-state in all subjects with an observed mean Cssave of 9.14 ± 1.83 µmol l−1. The mean Cssmax observed was 13.98 ± 2.43 µmol l−1 and the Cssmin 6.78 ± 1.79 µmol l−1. The mean AUC observed for each 12 h dosing interval was 109.6 ± 24.6 µmol h l−1. There was a significant relationship between the Cssave trimethoprim plasma concentration and the fold increase in rosiglitazone AUC in subjects having the CYP2C8*1/*1 or *1/*2 genotype (r2 = 0.97, P = 0.0021; Figure 3). The relationship was not significant when subjects with the CYP2C8*1/*3 genotype were included (r2 = 0.08, P = 0.48). There was no relationship between trimethoprim Cssmax or Cssmin values and the fold increase in rosiglitazone AUC.

Figure 3.

Relationship between the fold increase in rosiglitazone AUC and the trimethoprim Cssave concentration. The linear regression line is based on data from subjects having the CYP2C8*1/*1 or *1/*2 genotype (▪; r2 = 0.97, P = 0.0021). The relationship was not significant when subjects with the CYP2C8*1/*3 genotype (▿) were included (r2 = 0.08, P = 0.48)

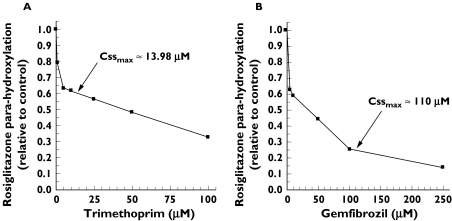

In human liver microsomes, the apparent Km determined for rosiglitazone (mean (standard error)) was 11.9 µm (1.8). It should be noted that only one of the six substrate concentrations used in the incubations was below the estimated Km value. The inhibition profiles of rosiglitazone (10 µm) in the presence of trimethoprim and gemfibrozil at various concentrations are depicted in Figure 4. The apparent Ki and IC50 values calculated for trimethoprim were 29.0 µm (1.4) and 51.5 µm (2.8), respectively. The apparent Ki and IC50 values determined for gemfibrozil were 69.0 µm (1.1) and 119 µm (2.0), respectively. The mechanism of inhibition of CYP2C8 mediated metabolism of rosiglitazone was competitive and noncompetitive for trimethoprim and gemfibrozil, respectively.

Figure 4.

Rosiglitazone para-hydroxylation by human liver microsomes expressed as a percentage of control in the presence of (A) trimethoprim and (B) gemfibrozil. Arrows indicate (A) Cssmax for trimethoprim administered 200 mg twice daily, which was determined in the present study, and (B) Cssmax for gemfibrozil administered 600 mg twice daily, taken from [18]

Discussion

Plasma rosiglitazone concentrations were increased in the presence of trimethoprim. Whereas the AUC and half-life were significantly increased, trimethoprim administration did not appear to affect rosiglitazone absorption, since tmax, Cmax, and Vd/F were not different. In vitro, trimethoprim competitively inhibited the CYP2C8 catalysed para-hydroxylation of rosiglitazone. Thus, the in vitro and in vivo results demonstrate that trimethoprim is an inhibitor of the CYP2C8 mediated metabolism of rosiglitazone.

The in vitro inhibition data for trimethoprim in the present study are consistent with previous reports [19]. Since gemfibrozil administration has been shown to increase rosiglitazone plasma concentrations in healthy human subjects [18], the effect of gemfibrozil on rosiglitazone metabolism in vitro was also evaluated. Apparent Ki and IC50 values for gemfibrozil (69 µm and 119 µm) were comparable with the previously reported values of 69 µm and 91 µm, respectively [27]. These data indicate that trimethoprim is a more potent in vitro inhibitor of CYP2C8 compared to gemfibrozil, which suggests that trimethoprim may be more suitable as an in vivo inhibitor for this enzyme. However, gemfibrozil appears to be the more effective in vivo inhibitor of CYP2C8. Niemi et al. found that the AUC of rosiglitazone after a single dose (4 mg) was increased 2.3-fold in the presence of gemfibrozil (600 mg given twice daily for 3 days) [18]. The difference in the magnitude of inhibition observed with trimethoprim and gemfibrozil may be due to the combined inhibition of CYP2C9 and CYP2C8 by the latter [27, 28], although rosiglitazone is only metabolized by CYP2C9 to a minor extent [11], or may be related to the plasma concentrations of the inhibitors. In the previous study, subjects achieved a mean peak total gemfibrozil concentration of 110 µm, which is greater than the apparent Ki (69 µm), and a mean average total gemfibrozil concentration of 31 µm. Thus, based on total drug concentration, gemfibrozil would be expected to inhibit CYP2C8 [18] to a greater extent than trimethoprim, since the maximum and average total concentrations of trimethoprim attained in plasma with normal therapeutic doses are less than the apparent Ki. Using the equation AUCI/AUC = 1 + [I]/Ki[29] and the apparent Ki (69 µm), the predicted fold-increase in rosiglitazone plasma AUC would be 2.6 and 1.5, based on peak and average total plasma gemfibrozil concentrations (inhibitor or I), respectively.

In the present study, the mean average total trimethoprim concentration (Cssave) after administration for 5 days was 9.14 µm, which is similar to the previously reported value of 10.7 µm[20]. The mean peak total concentration was 13.98 µm, and this and Cssave are less than the apparent Ki (29–32 µm). Wen et al. based on the liver/plasma partition ratio of 6.5–1 observed in the rhesus monkey [21] and an estimated peak total plasma concentration of 20 µm, predicted that subjects would achieve peak hepatic trimethoprim concentrations of approximately 130 µm, which would produce CYP2C8 inhibition of greater than 80%[19]. In the present study the rosiglitazone AUC was increased by only 1.3-fold. However, the predicted magnitude of CYP2C8 inhibition as expressed by the fold increase in rosiglitazone AUC would be 1.3 based on the average total plasma concentration. Factoring in estimated hepatic accumulation and plasma protein binding (trimethoprim fraction unbound = 0.55), the predicted increase in AUC would be 2.7 or 2.1-fold based on peak or average unbound plasma concentration, respectively. Thus, these data suggest that hepatic accumulation during short-term trimethoprim administration is not important and that the magnitude of inhibition is more closely related to the average total plasma concentration. Since the plasma concentrations of trimethoprim that are achieved with normal therapeutic doses are less than the apparent Ki, the use of trimethoprim as an in vivo CYP2C8 inhibitor may be limited. Although gemfibrozil inhibits both CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 in vitro[27, 28], it may still have utility as a selective CYP2C8 inhibitor, since in vivo studies have demonstrated a more pronounced effect on the metabolism of CYP2C8 substrates (e.g. cerivastatin, repaglinide, and rosiglitazone) compared with CYP2C9 substrates (e.g. glimepiride) [30–32].

The trimethoprim–rosiglitazone interaction may have clinical relevance. The most common serious adverse effects associated with the thiazolidinediones rosiglitazone and pioglitazone are related to volume expansion (e.g. congestive heart failure, pulmonary oedema, and pleural effusions) [33], which appears to be concentration-dependent [34]. Thus, patients taking rosiglitazone who are then treated with trimethoprim may be at greater risk of adverse effects such as oedema. The dosage of trimethoprim used in this study (200 mg twice daily for 5 days) is similar to the usual dosage of trimethoprim (160 mg twice daily) administered in combination with sulfamethoxazole for the treatment of common infections. Since the administration of trimethoprim with rosiglitazone may increase the risk of adverse events, the former should be used with caution, especially in patients treated with a high rosiglitazone dose (e.g. 8 mg daily), or who will receive trimethoprim for a prolonged period of time.

Although the sample size in this study is small, CYP2C8 genotype did not appear to affect the metabolism of rosiglitazone (in the absence of trimethoprim), as there was no significant difference in rosiglitazone exposure in the subjects with a variant allele compared with the wild-type subjects (Figure 2A, control). However, the data suggest that the magnitude of inhibition by trimethoprim may be influenced by genotype, as wild type subjects tended to have a greater increase in rosiglitazone AUC relative to control compared with subjects carrying either the CYP2C8*2 or CYP2C8*3 allele (data not shown). In addition, there was a strong correlation between the magnitude of inhibition, expressed as the fold increase in rosiglitazone AUC, and the average trimethoprim plasma concentration (Cssave), but only in the subjects having the CYP2C8*1/*1 or *1/*2 genotype (Figure 3). Differences in activity associated with the CYP2C8*2 and CYP2C8*3 alleles may contribute to these observations. In vitro, the CYP2C8*2 polymorphism is associated with decreased affinity (increased Km) for paclitaxel with no change in Vmax, resulting in a two-fold lower 6α-hydroxypaclitaxel intrinsic clearance. The CYP2C8*3 variant is associated with markedly decreased paclitaxel turnover [4]. Niemi et al. recently evaluated the effect of CYP2C8 genotype on the pharmacokinetics of the CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 substrate repaglinide. They found that subjects possessing the CYP2C8*3 allele had lower repaglinide exposure compared with the control group, which suggests that the CYP2C8*3 allele may result in greater CYP2C8 activity [35]. Data from this study suggest that genotype may influence the ability of trimethoprim to inhibit CYP2C8 and those individuals carrying the CYP2C8*3 allele may be less sensitive to the inhibitory effects of trimethoprim on rosiglitazone metabolism.

Overall, this study demonstrates that trimethoprim competitively inhibits the CYP2C8 mediated metabolism of rosiglitazone in vitro and significantly increases rosiglitazone exposure in healthy subjects during short-term administration. Therefore, trimethoprim should be used with caution in patients with type 2 diabetes who are taking rosiglitazone.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by NIH Research Grant R01 MH63458, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the Office of Dietary Supplements and NIH/NCRR/GCRC#5M01RR00056.

References

- 1.Klose TS, Blaisdell JA, Goldstein JA. Gene structure of CYP2C8 and extrahepatic distribution of the human CYP2Cs. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 1999;13(6):289–95. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0461(1999)13:6<289::aid-jbt1>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lapple F, von Richter O, Fromm MF, Richter T, Thon KP, Wisser H, et al. Differential expression and function of CYP2C isoforms in human intestine and liver. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13(9):565–75. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mace K, Bowman ED, Vautravers P, Shields PG, Harris CC, Pfeifer AM. Characterisation of xenobiotic-metabolising enzyme expression in human bronchial mucosa and peripheral lung tissues. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(6):914–20. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai D, Zeldin DC, Blaisdell JA, Chanas B, Coulter SJ, Ghanayem BI, et al. Polymorphisms in human CYP2C8 decrease metabolism of the anticancer drug paclitaxel and arachidonic acid. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11(7):597–607. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200110000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahadur N, Leathart JB, Mutch E, Steimel-Crespi D, Dunn SA, Gilissen R, et al. CYP2C8 polymorphisms in Caucasians and their relationship with paclitaxel 6alpha-hydroxylase activity in human liver microsomes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64(11):1579–89. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakajima M, Fujiki Y, Noda K, Ohtsuka H, Ohkuni H, Kyo S, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of CYP2C8 in Japanese population. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31(6):687–90. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.6.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman A, Korzekwa KR, Grogan J, Gonzalez FJ, Harris JW. Selective biotransformation of taxol to 6 alpha-hydroxytaxol by human cytochrome P450 2C8. Cancer Res. 1994;54(21):5543–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li XQ, Björkman A, Andersson TB, Ridderström M, Masimirembwa CM. Amodiaquine clearance and its metabolism to N-desethylamodiaquine is mediated by CYP2C8. a new high affinity and turnover enzyme-specific probe substrate. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300(2):399–407. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.2.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bidstrup TB, Bjornsdottir I, Sidelmann UG, Thomsen MS, Hansen KT. CYP2C8 and CYP3A4 are the principal enzymes involved in the human in vitro biotransformation of the insulin secretagogue repaglinide. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;56(3):305–14. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2003.01862.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Projean D, Morin PE, Tu TM, Ducharme J. Identification of CYP3A4 and CYP2C8 as the major cytochrome P450 s responsible for morphine N-demethylation in human liver microsomes. Xenobiotica. 2003;33(8):841–54. doi: 10.1080/0049825031000121608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldwin SJ, Clarke SE, Chenery RJ. Characterization of the cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the in vitro metabolism of rosiglitazone. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;48(3):424–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00030.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox PJ, Ryan DA, Hollis FJ, Harris AM, Miller AK, Vousden M, et al. Absorption, disposition, and metabolism of rosiglitazone, a potent thiazolidinedione insulin sensitizer, in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28(7):772–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bolton GC, Keogh JP, East PD, Hollis FJ, Shore AD. The fate of a thiazolidinedione antidiabetic agent in rat and dog. Xenobiotica. 1996;26(6):627–36. doi: 10.3109/00498259609046738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nadin L, Murray M. Participation of CYP2C8 in retinoic acid 4-hydroxylation in human hepatic microsomes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58(7):1201–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeldin DC, DuBois RN, Falck JR, Capdevila JH. Molecular cloning, expression and characterization of an endogenous human cytochrome P450 arachidonic acid epoxygenase isoform. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;322(1):76–86. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balfour JA, Plosker GL. Rosiglitazone. Drugs. 1999;57(6):921–30. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199957060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watkins PB. Noninvasive tests of CYP3A enzymes. Pharmacogenetics. 1994;4(4):171–84. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199408000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niemi M, Backman JT, Granfors M, Laitila J, Neuvonen M, Neuvonen PJ. Gemfibrozil considerably increases the plasma concentrations of rosiglitazone. Diabetologia. 2003;46(10):1319–23. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1181-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen X, Wang JS, Backman JT, Laitila J, Neuvonen PJ. Trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole are selective inhibitors of CYP2C8 and CYP2C9, respectively. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30(6):631–5. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.6.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watson ID, Stewart MJ, Wiles A, McIntosh SJ. Pharmacokinetics of two dosage levels of trimethoprim to ‘steady-state’ in normal volunteers. J Int Med Res. 1983;11(3):137–44. doi: 10.1177/030006058301100302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craig WA, Kunin CM. Distribution of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in tissues of rhesus monkeys. J Infect Dis. 1973;128(Suppl):575–79. doi: 10.1093/infdis/128.supplement_3.s575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niemi M, Kajosaari L, Neuvonen M, Backman JT, Neuvonen PJ. The CYP2C8 inhibitor trimethoprim increases the plasma concentrations of repaglinide in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57(4):441–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.02027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hruska MW, Frye RF. Simplified method for determination of rosiglitazone in human plasma. J Chromatogr B. 2004;803(2):317–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hruska MW, Frye RF. Determination of trimethoprim in low-Volume human plasma by liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B. 2004;807(2):301–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ronaghi M. Pyrosequencing sheds light on DNA sequencing. Genome Res. 2001;11(1):3–11. doi: 10.1101/gr.11.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haglund S, Lindqvist M, Almer S, Peterson C, Taipalensuu J. Pyrosequencing of TPMT alleles in a general Swedish population and in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Chem. 2004;50(2):288–95. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.023846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang JS, Neuvonen M, Wen X, Backman JT, Neuvonen PJ. Gemfibrozil inhibits CYP2C8-mediated cerivastatin metabolism in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30(12):1352–6. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.12.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen X, Wang JS, Backman JT, Kivistö KT, Neuvonen PJ. Gemfibrozil is a potent inhibitor of human cytochrome P450 2C9. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29(11):1359–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ito K, Brown HS, Houston JB. Database analyses for the prediction of in vivo drug–drug interactions from in vitro data. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57(4):473–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2003.02041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niemi M, Backman JT, Neuvonen M, Neuvonen PJ. Effects of gemfibrozil, itraconazole, and their combination on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of repaglinide: potentially hazardous interaction between gemfibrozil and repaglinide. Diabetologia. 2003;46(3):347–51. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Backman JT, Kyrklund C, Neuvonen M, Neuvonen PJ. Gemfibrozil greatly increases plasma concentrations of cerivastatin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;72(6):685–91. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2002.128469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niemi M, Neuvonen PJ, Kivistö KT. Effect of gemfibrozil on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of glimepiride. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;70(5):439–45. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.119723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niemeyer NV, Janney LM. Thiazolidinedione-induced edema. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(7):924–9. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.11.924.33626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Idris I, Gray S, Donnelly R. Rosiglitazone and pulmonary oedema: an acute dose-dependent effect on human endothelial cell permeability. Diabetologia. 2003;46(2):288–90. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-1008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niemi M, Leathart JB, Neuvonen M, Backman JT, Daly AK, Neuvonen PJ. Polymorphism in CYP2C8 is associated with reduced plasma concentrations of repaglinide. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74(4):380–7. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]