Abstract

Aims

To evaluate the population pharmacokinetics of levocetirizine in young children receiving long-term treatment with cetirizine.

Methods

Data were available from a randomized, double-blind, parallel group and placebo-controlled study of cetirizine in 343 young children between 12 and 24 months of age at entry, who were at high risk of developing asthma, but were not yet affected (ETAC® study). Infants received oral drops of cetirizine at 0.25 mg kg−1 twice daily for 18 months. Plasma concentration of the active enantiomer levocetirizine was determined in blood samples collected at months 3, 12 and 18 (1–3 samples per child). A one-compartment open model was fitted to the data using nonlinear mixed effects modelling (NONMEM). The influence of weight, age, gender, BSA and other covariates on CL/F and V/F was evaluated.

Results

CL/F increased linearly with weight by 0.044 l h−1 kg−1 over an intercept of 0.244 l h−1, and V/F increased linearly with weight by 0.639 l kg−1. Population estimates in children with weights of 8 and 20 kg were 0.60 and 1.13 l h−1 for CL/F, and 5.1 and 12.8 l for V/F, respectively, with interpatient variabilities of 24.4% and 14.7%. Weight-normalized estimates of CL/F and V/F were higher than in adults. The estimated relative bioavailability was 0.28 in 12% of instances of suspected noncompliance. Levocetirizine pharmacokinetics were not influenced by severe allergy or aeroallergen sensitization. Results on the effects of concomitant medications or diseases were inconclusive due to limited positive cases. AUCss, calculated in compliant subjects using posterior estimates of the final model, was 1952 (1227–3319) µg l−1 h (mean, min-max), a value similar to that in adults after intake of 5 mg oral solution (2036 (1414–2827) µg l−1 h.

Conclusions

The model suggests that administration of levocetirizine 0.125 mg kg−1 twice daily in children 12–48 months of age or weighing 8–20 kg yields the same exposure as in adults taking the recommended dose of 5 mg once daily.

Keywords: antihistamine, cetirizine, ETAC, levocetirizine, paediatric population pharmacokinetics

Introduction

Following a recent survey in five European paediatric wards, over half of the patients were receiving an unlicensed or off label drug prescription [1]. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism as well as therapeutic response in young children may differ from adults. Lack of paediatric data may result in adverse events or damage in young children even if the adult safety profile of the drug is well documented. Antihistamines are widely used, even in very young children, even though very few efficacy data are available in this population. Cetirizine is a second generation antihistamine with properties that may decrease or prevent the development of allergic asthma in children with atopic dermatitis [2]. The pharmacokinetics of racemic cetirizine in infants and children have been studied in clinical trials where frequent blood sampling was undertaken and conventional analysis methods were used [3]. A retrospective population pharmacokinetic analysis of racemic cetirizine utilizing information from six previously conducted cetirizine clinical trials in children aged 0.5–12 years, including single and multiple dose studies with frequent and sparse sampling, has also been conducted [4]. Recently, the pharmacological activity of cetirizine was shown to be due to its R enantiomer (levocetirizine, Xyzal®) [5, 6]. Levocetirizine was shown to be stable with respect to enantiomeric interconversion, to be negligibly metabolized and excreted unchanged in the urine, and to have a smaller distribution volume and lower clearance than the distomer [7].

Levocetirizine population pharmacokinetics have been investigated in young children after racemic cetirizine administration, in the prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Early Treatment of the Atopic Child (ETAC®) Study [8, 9]. The primary objective of the present retrospective analysis was to characterize the population pharmacokinetics of levocetirizine in atopic children using sparse data from the ETAC® study.

Methods

Study population

Male and female children aged 12–24 months (at entry) and at high risk of developing asthma but not yet affected, were included in the ETAC® study. Data from 343 children were available out of a total of 399 treated with cetirizine 0.5 mg kg−1 day−1. Plasma concentrations and dosing information were available from 248, 279 and 226 children at the 3rd (visit 3), 12th (visit 6) and 18th (visit 8) month of treatment, respectively.

Study design, dosing and blood sampling

ETAC® was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel group and placebo-controlled study. Full details have been published elsewhere [8, 9]. Cetirizine dihydrochloride (50% levocetirizine and 50% dextrocetirizine) was administered orally (0.25 mg kg−1 twice daily) for 18 months, delivered in the form of a 10 mg ml−1 oral drops formulation. Treatment commenced and follow-up visits were scheduled after 1 month, 3 months and thereafter every 13 weeks during the 18 month-treatment period. Afterwards, patients entered a long-term follow-up period without study medication. Demographic data on age, gender, weight, height and serum creatinine concentration and data on allergic sensitization, severity of allergy, concomitant medication and concomitant diseases were collected at each visit. Plasma from venous blood samples was collected at months 3, 6 and 18 of treatment or before, in case of premature discontinuation. The date and hour of the last dose were recorded on the requisition form at each visit to the laboratory.

The ETAC® study protocol was approved by the institutional review board in each of the participating centres. The study was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice, including Ethical Approval. The ETAC® study and this population analysis were financially supported by UCB S.A. Pharma Sector, Belgium.

Drug analysis

The concentrations of cetirizine enantiomers and of the metabolite ucb P026 (nonresolved chromatographically) were determined using a validated analytical method in accordance with current GLP guidelines.

After addition of internal standard (ucb 20028), the samples were deproteinized by the addition of acetonitrile. After centrifugation, the supernatant was evaporated to dryness and redissolved in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid adjusted to pH 3 and 5% acetonitrile. On-line prepurification was performed on a Lichrospher 100 CN, 4 × 4 mm, 5 µm particle size precolumn, using a standard column switching method and a gradient programme. Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Chiralcel OD 0.46 × 25 cm analytical column protected by a second Lichrospher guard column, using a mobile phase of 27% acetonitrile and 73% pH 3 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. The column effluent was introduced into the tandem mass spectrometer (SciEx API 300) using a turbo ion spray interface, and signals were detected by positive ion MRM scan. Typical retention times were 11 min (ucb P026), 13.5 min (IS), and 15 and 16.5 min (cetirizine enantiomers). The quantification range was 3–1000 ng ml−1 for all three analytes. Since samples were diluted four-fold in blank plasma, their limit of determination was raised to 12 ng ml−1. The absence of a matrix effect and ion suppression, the stability of the analytes on repeated freeze/thaw, their stability in reconstituted samples and on long-term storage at −20 °C were documented. Quality control samples at 7.5, 150 and 750 ng ml−1 were assayed in duplicate with each batch of study samples (943 samples, 18 runs). Overall, imprecision and inaccuracy were 8.3% and −0.9%, 6.7% and + 0.8%, and 9.1% and +2.6% for levocetirizine; 9.9% and −1.9%, 7.0% and +0.5%, and 8.3% and +3.0% for dextrocetirizine; 8.9% and −0.3%, 6.1% and −1.0%, and 7.1% and +0.7% for total P026, respectively.

Database construction

For each individual record, time of dose and amount, sampling time, levo- and dextrocetirizine concentrations, demographic information (age, gender, weight, height, serum creatinine concentration (Crs)) as well as data on allergic sensitization (grass pollen and/or house dust mite specific IgEs, IgEGP and IgEHDM), severity of allergy (eosinophil counts µl−1), concomitant use of corticosteroids, penicillins, macrolides and hydroxyzine, and occurrence of diarrhoea or gastro-enteritis were available at months 3, 12 and 18. The database for population analysis was constructed using the plasma concentration-time data for the biologically active cetirizine enantiomer, levocetirizine. The dose of levocetirizine was 50% of the administrated racemic cetirizine dose. Concentration-time data from 3.9% of the children who had sampling times lower than zero or a greater than 12 h time difference between reported blood sample and drug intake, and those with concentrations ≤12 ng ml−1 (dilution-corrected lower limit of determination) were excluded from the dataset.

Population pharmacokinetic modelling

Non-linear mixed effects modelling was performed by extended least squares regression using the NONMEM program (version V, level 1.1) [13], with double precision and either first-order (FO) or first-order conditional (FOCE) estimation methods. A one-compartment model with a first order absorption process and first order elimination was fitted to the levocetirizine plasma concentration-time data. Based on visual inspection of the data and previous experience with racemic cetirizine [4] the model seemed to characterize steady-state concentration-time profiles adequately.

The continuous covariates tested are presented in Table 1. Body surface area (BSA, m2) and creatinine clearance (CLcr, ml min−1) were estimated using the following standard formula by Traub-Johnson [11, 12]:

Table 1.

Demographic information for children included in the population pharmacokinetics of levocetirizine

| Variable | Visit month | na | n missingb | Mean | SD | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 3 | 248 | 19.8 | 4.1 | 14.4 | 19.1 | 28.2 | |

| 12 | 279 | 29.0 | 4.3 | 21.5 | 27.8 | 40.4 | ||

| 18 | 226 | 35.3 | 4.3 | 29.1 | 34.6 | 46.3 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 3 | 248 | 11.9 | 1.6 | 8.2 | 11.8 | 18.0 | |

| 12 | 279 | 13.9 | 1.6 | 10.1 | 13.7 | 19.6 | ||

| 18 | 226 | 15.0 | 1.9 | 10.3 | 14.8 | 20.5 | ||

| BSA (m2) | 3 | 244 | 4 | 0.52 | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.52 | 0.70 |

| 12 | 276 | 3 | 0.59 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.59 | 0.76 | |

| 18 | 223 | 3 | 0.63 | 0.05 | 0.50 | 0.62 | 0.78 | |

| CLcr (ml min−1) | 3 | 230 | 18 | 28.2 | 5.8 | 14.3 | 27.3 | 45.7 |

| 12 | 270 | 9 | 30.2 | 4.3 | 19.2 | 30.1 | 44.7 | |

| 18 | 215 | 11 | 32.8 | 4.9 | 21.2 | 32.6 | 49.5 |

Number of children with demographic information.

Number of children with missing demographic information.

The relationships between pharmacokinetic parameter (P) and continuous covariates (CCOV) were described by the following general linear equation:

In case of missing data for BSA and CLcr the equation had the form

where MISS = 1 for subjects with missing data and 0 otherwise. This transformation allows the model estimate the average parameter value for the individuals with a missing covariate.

Children with eosinophil count >500 µl−1 were considered to present with severe allergy, and the remainder were classed as having no severe allergy. For allergic sensitization (ALLG), aeroallergen-positive children were defined as having IgEGP and/or IgEDM ≥0.35 KUA l−1[8], and the remainder were considered aeroallergen-negative. Concomitant disease (DIAR) was assigned to children with diarrhoea/gastro-enteritis at a particular visit. Concomitant medications within the 8 days preceding a particular visit were the macrolides (MACR), oral corticosteroids (CORT), penicillins (PENC) and hydroxyzine (ATAR). The models for the relationships between pharmacokinetic parameters (P) and categorical covariates (COV), had the following general form:

where the presence of a covariate was coded as 1 and its absence as 0. In the case of missing data the covariate code was −1 and P = θmiss. Female was coded as 1 and male as 0.

Inter-patient variability in the pharmacokinetic parameters was modelled with the use of an exponential error model as follows [13, 14]:

The magnitude of interpatient variability in each parameter was an approximation taken as the square root of the variance, expressed as a coefficient of variation (%CV). Residual variability in levocetirizine plasma concentrations, representing a composite of model misspecification, variability in the analytical method and intrapatient variability, was modelled using a proportional, an additive or a combined error model. The 95% confidence interval (CI) in the parameter estimates was calculated as follows:

where Pav is the mean value of the parameter, s.e. (Pav) is the standard error of Pav, as estimated by NONMEM, t0.975 is the 97.5th percentile of the t-distribution with N−1 degrees of freedom. The precision of each parameter was calculated as the s.e. divided by the parameter estimate × 100.

The analysis strategy included selection of the basic structural model, univariate analysis, multivariate analysis with forward selection, and finally multivariate analysis with backward elimination [15].

The structural and statistical parameter values determined in the final model were used to obtain the individual predicted parameters by invoking the POSTHOC function in the $ESTIMATION procedure within NONMEM. The parameter estimates and variance from the final model were used to simulate steady-state levocetirizine profiles in children with mean body weights of 11.9, 13.9 and 15.0 kg (observed means at each visit) dosed with 3.15, 3.36 and 3.17 mg (0.25 mg kg−1) cetirizine twice daily at months 3, 12 and 18, using first order estimation.

Results

The database for the population pharmacokinetics included 753 records of plasma levocetirizine concentrations. Sparse data at steady state were available for 343 children from three visits. Overall, 66, 144 and 133 subjects provided 1, 2 and 3 measurements, respectively. Seventy-five % of the total number of samples were taken between 1 and 5 h postdose. No systematic gender differences in body weight, BSA and CLcr were observed. As expected, body weight, BSA and CLcr increased with age and these relationships appeared to be linear.

Initially, a one-compartment open model with first-order absorption and elimination (pharmacokinetic structural model), with CL/F, V/F and ka as the parameters, an exponential error term for interpatient variability on each parameter, and a combined (additive and proportional) error term on residual variability for all concentrations, was examined, using the FO estimation method in NONMEM. Subsequently, a similar model but with two error terms (additive and proportional terms in each) for residual variability for concentration ≤400 ng ml−1 and >400 ng ml−1 was examined and resulted in a decrease in the OBJF of 225. The 400 ng ml−1 threshold, which was selected based on sensitivity analysis, resulted in the highest decrease in the objective function. This threshold had no clinical or therapeutic implication. Following visual inspection of the data, an additional parameter of relative bioavailability was included in the model for children with suspected noncompliance (F1 = ΘF) compared with that in children with probable good compliance (F1 = 1), and resulted in a further decrease in the OBJF of 319. In this model the two proportional error terms for residual variability were poorly estimated and their removal did not significantly increase the OBJF. Hence, a model with four pharmacokinetic parameters (CL/F, V/F, ka and F), exponential error terms for interpatient variability on each parameter, except for F, and two additive error models for residual variability, one for concentrations ≤400 ng ml−1 and another for those >400 ng ml−1, was superior to all other models tested and was declared as BASE 1 and used in all subsequent analysis. The same model was examined using FOCE but there was no advantage in terms of the precision of the parameter estimates or associated variability. The precision of the structural parameter values and residual error terms for BASE 1 was good (CV% < 20%). The magnitudes of the interpatient variability in CL/F, V/F and ka were 26.1%, 37.3% and 112%, respectively.

Results of the univariate analyses are presented in Table 2. The rank order for the inclusion of the superior models in the BASE 2 model is also shown. Statistically significant associations were found between the covariates body weight, age, BSA, CLcr and the apparent clearance, and between body weight, age, BSA and the apparent volume of distribution of levocetirizine. For the effect of body weight on V/F, and of BSA on both CL/F and V/F, inclusion of an intercept offered no improvement. After consideration of the high correlation between BSA and body weight and their nearly identical effect on OBJF, it was decided that only the effect of body weight and not that of BSA on CL/F and V/F were to be evaluated further, since for most drugs dosing in children is mainly based on either weight or age and not BSA [16]. The linear model describing the effect of body weight on levocetirizine CL/F had the largest decrease in the OBJF and was termed the BASE 2 model for the subsequent forward selection analysis.

Table 2.

Summary of the univariate analysis for levocetirizine

| Effect | ΔOBJF | Symbol | Parameter estimate | s.e. | Ranka |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age on CL/F | −31.227 | θCL | 0.548 | 0.0541 | 3 |

| CL/F = θCL + θCL,AGE × AGE | θCL, AGE | 0.0104 | 0.00205 | ||

| Age on V/F | −10.352 | θV | 2.23 | 3.34 | 5 |

| V/F = θV + θV,AGE × AGE | θV, AGE | 0.228 | 0.140 | ||

| Weight on CL/F | −56.200 | θCL | 0.0991 | 0.110 | 1 |

| CL/F = θCL + θCL,WT × WT | θCL, WT | 0.0546 | 0.00864 | ||

| Weight on V/F | −22.698 | θV | 3 × 10−13 | 0.0781 | |

| V/F = θV + ΘV,WT × WT | θV, WT | 0.575 | 0.0598 | ||

| Weight on V/F- Linear model (θV = 0) | −22.698 | θV, WT | 0.575 | 0.0615 | 4 |

| BSA on CL/F | −57.048 | θCL,BSA | 1.43 | 0.0389 | |

| CL/F = θCL,BSA × BSA | θCL, miss | 1.16 | 0.0832 | ||

| BSA on V/F | −17.054 | θV,BSA | 13.5 | 1.44 | |

| V/F = θV,BSA × BSA | θV, miss | 16.7 | 9.48 | ||

| CLcr on CL/F | −39.616 | θCL | 0.478 | 0.0978 | 2 |

| CL/F = θCL + θCL,CLcr × CLcr | θCL, CLcr | 0.0126 | 0.00329 | ||

| θCL, miss | 0.405 | 0.128 | |||

| Gender on CL/F | −1.203 | θCL,M | 0.859 | 0.0292 | |

| CL/F = θCL,M (1-SEX) + θCL,F × SEX | −θCL,Φ | 0.818 | 0.0325 | ||

| Gender on V/F | −4.330 | θV,M | 9.70 | 1.34 | |

| V/F = θV,M (1-SEX) + θV,F × SEX | θV,Φ | 7.62 | 0.806 | ||

| Allergen sensitization on CL/F | −4.832 | θCL,NO | 0.821 | 0.0238 | |

| CL/F = θCL,NO × (1 − ALLG) + θCL,ALLG × ALLG | θCL,ALLG | 0.923 | 0.0521 | ||

| Hydroxyzine on CL/F | −0.002 | θCL,NO | 0.841 | 0.0235 | |

| CL/F = θCL,NO × (1-ATAR) + θCL, ATAR × ATAR | θCL,ATAR | 0.845 | 0.106 | ||

| Penicillins on CL/F | −0.082 | θCL,NO | 0.840 | 0.0241 | |

| CL/F = θCL,NO × (1-PENC) + θCL, PENC × PENC | θCL,PENC | 0.860 | 0.0820 | ||

| Corticosteroids on CL/F | −2.965 | θCL,NO | 0.843 | 0.0235 | |

| CL/F = θCL,NO × (1-CORT) + θCL, CORT × CORT | θCL,CORT | 0.611 | 0.0896 | ||

| Macrolides on CL/F | −2.279 | θCL,NO | 0.843 | 0.0239 | |

| CL/F = θCL,NO × (1-MACR) + θCL, MACR × MACR | θCL,MACR | 0.657 | 0.1210 | ||

| Diarrhoea/gastroenteritis on CL/F | −0.762 | θCL,NO | 0.844 | 0.0204 | |

| CL/F = θCL,NO × (1-DIAR) + θCL, DIAR × DIAR | θCL,DIAR | 0.793 | 0.0562 | ||

| Eosinophily on CL/F | −1.145 | θCL, NO | 0.835 | 0.0258 | |

| CL/F = θCL,NO × (1-EOS) + θCL,EOS × EOS | θCL, EOS | 0.865 | 0.0344 | ||

| θCL, miss | 0.0124 | 0.0708 |

Ranking according to the decrease in objective function (P < 0.005) as compared with the basic model.

In the multivariate analysis with forward selection, the covariates with significant effects were incorporated into BASE 2 in turn, starting with the effect of body weight on CL/F and continuing in the rank order established in the univariate analysis. In the presence of a body weight effect on clearance, the effects of CLcr and age on CL/F were not statistically significant at the 0.005 level. Although in the presence of a weight effect on CL/F, the effect of weight on V/F was found not to be statistically significant at the 0.005 level, there was a substantial decrease in the interpatient variability on V/F from 37.3% (basic model) to 14.7%. Hence, in the subsequent forward analysis the effect of age on V/F was evaluated in the presence of a weight effect on both CL/F and V/F. The effect of age on V/F was found not to be statistically significant at the 0.005 level, and thus no backward elimination analysis was necessary. The model with linear relationships between CL/F and weight (with an intercept) and between V/F and weight (without an intercept) was declared as the final model for levocetirizine.

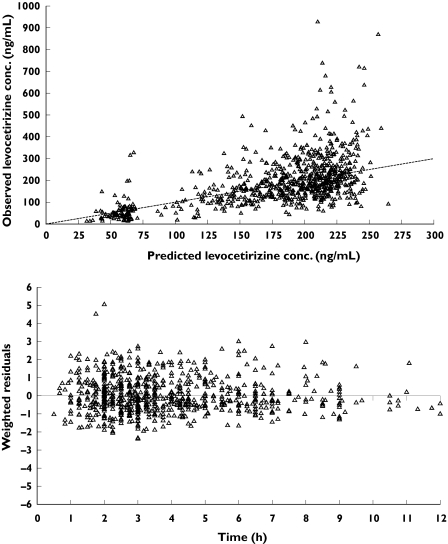

Scatter plots of weighted residuals vs time from the final model (Figure 1) and of WRES vs predicted concentrations (not presented) showed the WRES to be evenly distributed around zero, indicating the validity of the selected additive model for residual variability. Table 3 presents the estimates from the final pharmacokinetic model for levocetirizine in children. As seen from the 95% confidence intervals, the parameters of the structural model and residual variability were estimated with adequate precision (%CV ≤ 0.5 44.3%). The relationships between CL/F and V/F and body weight were as follows:

Figure 1.

Diagnostic plots of observed vs predicted levocetirizine concentrations (upper panel) and weighted residuals vs time (lower panel) from the final model

Table 3.

Final estimates of population pharmacokinetic parameters for levocetirizine in children aged 1–4 years after multiple oral doses of cetirizine

| Parameter | Estimate [95% CI] | Precision (% CV) |

|---|---|---|

| CL/F = θCL + θCL, WT × WEIGHT (l h−1) | ||

| θCL (l h−1) | 0.244 [0.032, 0.456] | 44.3 |

| θCL, WT (L/h/kg) | 0.0442 [0.0279, 0.0605] | 18.8 |

| V/F = θV × WEIGHT (l) | ||

| θV (l kg−1) | 0.639 [0.503, 0.775] | 10.9 |

| Fnon-comp = θF1 | 0.281 [0.230, 0.332] | 9.3 |

| ka = θka + CL/V (h−1)a | ||

| θka (h−1) | 1.140 [0.668, 1.612] | 21.1 |

| Inter-patient variability in CL/F (% CV)b | 24.4 | 24.9 |

| Inter-patient variability in V/F (% CV)b | 14.7 | >100% |

| Inter-patient variability in ka (% CV)b | 105.4 | 61.8 |

| Residual variability in concentration ≤ 400 ng ml−1 (ng ml−1) | 53.5 | 13.0 |

| Residual variability in concentration > 400 ng ml−1 (ng ml−1) | 316 | 15.1 |

ka was modelled as ka = θka + CL/V to guard for flip-flop. The term CL/V contributes on average less than 5% to the value of ka.

The percentage CV for both interpatient variability is an approximation taken as the square root of the variance ×100. The approximation is due to the expansion of the exponential function only to first-order.

Precision was calculated as the s.e. divided by the parameter estimate ×100.

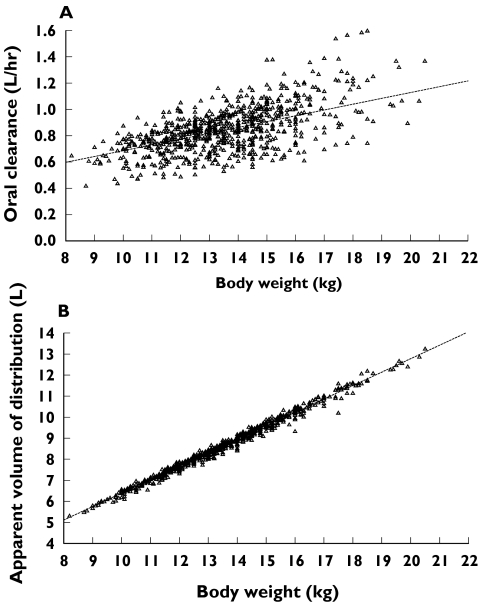

The interpatient variability for levocetirizine CL/F and V/F was low at 24.4% and 14.7%, respectively, and decreased from 26.1% and 37.3%, respectively, in the BASE 1 model. As is the case for most drugs, the interpatient variability for levocetirizine ka was high (105.4%). The interpatient variance parameters for levocetirizine were estimated with good precision for CL/F (CV% = 24.9%), but relatively low precision for V/F (CV% > 100%). The additive residual variability in levocetirizine concentrations was estimated to be 53.5 ng ml−1 for plasma concentrations ≤400 ng ml−1 and 316 ng ml−1 for plasma concentration >400 ng ml−1. CL/F increased by 0.0442 l h−1 kg−1 over an intercept of 0.244 l h−1, whereas V/F increased by 0.639 l kg−1, regardless of gender. Since the rate of increase in CL/F with body weight was slower than the rate of increase of V/F with this variable, a modest increase in half-life with body weight was observed. The posterior estimates of CL/F and V/F and the model-predicted relationships are presented in Figure 2. No other trends for associations between levocetirizine pharmacokinetic parameters and particular covariates were observed.

Figure 2.

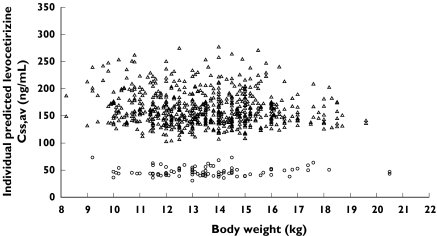

Plots of posterior estimates of oral clearance (A) and apparent volume of distribution (B) vs body weight from the final model. Dotted lines are the respective model-predicted relationships with body weight

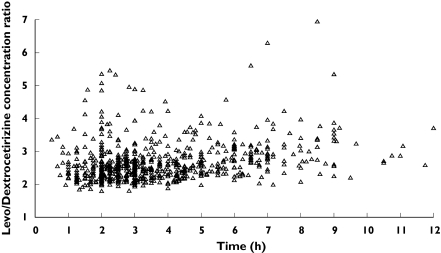

Scatterplots of individual predicted average concentrations at steady state (Css,av) vs body weight are presented in Figure 3. Similar levocetirizine average concentrations at steady-state are predicted for all compliant children, whereas the children for whom noncompliance is suspected have lower concentrations. Plots of the levocetirizine : dextrocetirizine observed concentration ratios vs time are presented in Figure 4. Although high variability was observed, for the majority of data, the ratio was higher than 2 and mainly ranging between 2 and 4.

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of individual predicted mean steady-state levocetirizine concentration vs body weight. Compliance = likely (▵), compliance = unlikely (○)

Figure 4.

Scatterplot of levocetirizine/dextrocetirizine concentration ratio vs. post-dose time

Discussion

Levocetirizine concentration-time data were available after multiple dosing of racemic cetirizine (0.25 mg kg−1) twice daily for 18 months. The data consisted of 1–3 sparse steady-state samples per child. Patient demographics were available as covariates for each visit, as well as creatinine clearance, aeroallergen sensitization, severe allergy, diarrhoea/gastro-enteritis, concomitant use of corticosteroids, penicillins, macrolides or hydroxyzine. These conditions or comorbidity-indicating drugs were considered to have a potential influence on the absorption of the drug. Metabolic interaction potential from these drugs was ruled out, given the negligible biotransformation of levocetirizine [7]. However, hydroxyzine had the potential to interfere with the analysis of cetirizine.

The association between CL/F and V/F and these covariates were examined. The only significant effects found on final analysis was that of body weight on both CL/F and V/F, both giving a linear relationship.

Severe allergy and aeroallergen sensitization had no significant effect on the pharmacokinetics of levocetirizine. The limited number of cases of concomitant medication or concomitant disease rendered any comparisons inconclusive. However, graphical examination of each subpopulation (not shown) indicated that the influence of each condition on plasma concentrations was probably of no clinical significance. The majority of the observed levocetirizine concentrations at each visit were within the 95% model prediction intervals. Hence in future studies with levocetirizine as a single enantiomer in children with body weight from 8 to 20 kg (1–4 years), the observed steady-state levocetirizine concentrations are anticipated to fall within these 95% prediction intervals.

The relative bioavailability term signifying possible noncompliance in 92 out of 753 cases (12%) was estimated to be 28.1%. Interpatient variability for this parameter could not be estimated. Levocetirizine concentrations in these cases were much lower than in the majority of the population (Figure 3) and even within the same individual, when data were available on more than one visit and sampling times were similar. Possibly, before a specific visit where a child was identified as noncompliant the child was either not dosed adequately by the parents, the last dose before the blood sample on that visit might not have been taken, or the dosing time was incorrectly recorded.

Like cetirizine, levocetirizine was rapidly absorbed in children. The population estimate of the absorption rate constant of cetirizine from a recent population pharmacokinetic analysis [4] was 2.14 h−1, with a very high interpatient variability of 145%. In the present analysis, the absorption rate constant for levocetirizine was estimated to be 1.14 h−1 with an interpatient variability of 105.4%.

The population estimate of levocetirizine CL/F in this young child population increased by 0.0442 l h−1 kg−1 over an intercept of 0.244 l h−1. Inter-patient variability in levocetirizine CL/F seen in the basic model (26.1%) was partly explained by the significant association between CL/F and weight. There were no significant differences in levocetirizine CL/F between male and female children. The population estimate for levocetirizine V/F for this child population was 0.639 l kg−1, and the interpatient variability in the basic model (37.3%) was substantially explained by the significant association between V/F and weight.

The estimates for levocetirizine CL/F and V/F for mean body weights of 11.9, 13.9 and 15.0 kg (months 3, 12 and 18, corresponding to mean ages of 1.65, 2.42 and 2.94 years) were 0.77, 0.86 and 0.91 l h−1 and 7.60, 8.88 and 9.59 l, respectively. Like cetirizine [4], the rate of increase in levocetirizine CL/F with body weight, or age, was estimated to be slower than the rate of increase of V/F, which explains the increase in half-life with body weight and age.

The typical values for the weight-normalized CL/F and V/F at month 12 were about 60% higher than in adults [7]. A similar pattern has been described for other drugs where younger children exhibit higher clearance and/or volume of distribution than older children and adults and therefore would require a higher dose kg−1 body weight to achieve comparable steady-state concentrations [17,22].

The post hoc individually predicted AUCsss in the subgroup of compliant children receiving levocetirizine (0.125 mg kg−1) twice daily were in close agreement with the AUCs after a single dose of levocetirizine oral solution in adults at the recommended dose of 5 mg once daily [7].

In conclusion, the model indicates that administration of levocetirizine at 0.125 mg kg−1 twice daily in atopic children aged 12–48 months, with body weight from 8 to 20 kg, achieves the same exposure to the drug as in adults receiving 5 mg once daily. The severity of the disease, comorbidities or concomitant medications did not have a detectable influence on exposure to levocetirizine.

References

- 1.Conroy S, Choonara I, Impicciatore P, Mohn A, Arnell H, Rane A, et al. Survey of unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries. Br Med J. 2000;320:79–82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curran MP, Scott LJ, Perry CM. Cetirizine: a review of its use in allergic disorders. Drugs. 2004;64:523–61. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spencer CM, Noble S. Cetirizine. A review of its use in children with allergic disorders. Paediatric Drugs. 1999;1:51–73. doi: 10.2165/00128072-199901010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitsiu M, Hussein Z, Majid M, Aarons L, de Longueville M, Stockis A. Retrospective population pharmacokinetic analysis of cetirizine in children from 6 months to 12 years. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:402–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.02017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devalia JL, De Vos C, Hanotte F, Baltes E. A randomised, double-blind, crossover comparison among cetirizine, levocetirizine, and ucb 28557 on histamine-induced cutaneous responses in healthy adult volunteers. Allergy. 2001;56:50–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang DY, Hanotte F, De Vos C, Clement P. Effect of cetirizine, levocetirizine, and dextrocetirizine on histamine-induced nasal response in healthy adult volunteers. Allergy. 2001;56:339–43. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baltes E, Coupez R, Giezek H, Voss G, Meyerhoff C, Strolin Benedetti M. Absorption and disposition of levocetirizine, the eutomer of cetirizine, administered alone or as cetirizine to healthy volunteers. Fund Clin Pharmacol. 2001;15:269–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2001.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warner JO ETAC Study Group. A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of cetirizine in preventing the onset of asthma in children with atopic dermatitis: 18 months’ treatment and 18 months’ post-treatment follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:929–37. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.120015. on behalf of the. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simons FER ETAC Study Group. Prospective, long-term safety evaluation of the H1-receptor antagonist cetirizine in very young children with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:433–40. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70389-1. on behalf of the. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevenson J, Cornah D, Evrard P, Vanderheyden V, Billard C, Bax M, et al. Long-term evaluation of the impact of the H1-receptor antagonist cetirizine on the behavioral, cognitive and psychomotor development of very young children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Res. 2002;52:251–7. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200208000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson WE, Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Arvin AM. Nelson Textbook of Paediatrics. 15. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1996. p. 2079. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traub SL, Johnson CE. Comparison of methods of estimating creatinine clearance in children. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1980;37:195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheiner L, Beal S. NONMEM Project Group. San Francisco: University of California; 1998. NONMEM, Version 5.1. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grasela TH, Sheiner LB. Pharmacostatistical modeling for observational data. J Pharmacokin Biopharm. 1991;19(June Supplement):25s–6s. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austin, TX, USA: BAST Inc; 1996. Modeling strategy for NONMEM programme. July. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox E, Balis FM. Drug therapy in neonates and pediatric patients. In: Atkinson AJ, Daniels CE, Dederick RL, Grudzinkas CV, Markey SP, editors. Principles of Clinical Pharmacology. London: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McFadyen ML, Miller R, Ludden TM. Ketotifen pharmacokinetics in children with atopic perennial asthma. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;52:383–6. doi: 10.1007/s002280050305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt A, Joel S, dick G, Goldman A. Population pharmacokinetics of oral morphine and its glucuronide in children receiving morphine as immediate-release liquid or sustained- release tablets for cancer pain. J Pediatr. 1999;135:12–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haig GM, Bockbrader HN, Wesche DL, Boellner SW, Ouellet D, Brown RR, Randinitis EJ, Posvar EL. Single-dose gabapentin pharmacokinetics and safety in healthy infants and children. J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;41:507–14. doi: 10.1177/00912700122010384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirochnick M, Cooper E, Capparelli E, McIntosh K, Lindsey J, Xu J, Jacobus D, Mofenson L, Bonagura VR, Nachman S, Yogev R, Sullivan JL, Spector SA. Population pharmacokinetics of dapsone in children with human immunodefficiency virus infection. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;70:24–32. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.115891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jungbluth GL, Welshman IR, Hopkins NK. Linezolid pharmacokinetics in paediatric patients: an overview. Paediatr Infec Dis J. 2003;22:S153–7. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000086954.43010.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hung TY, Davis TM, Ilett KF, Karunajeewa H, Hewitt S, Denis MB, Lim C, Socheat D. Population pharmacokinetics of piperaquine in adults and children with uncomplicated falciparium or vivax malaria. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:253–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.02004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]