Short abstract

Life expectancy and poorer outcomes associated with ethnicity are important issues for many countries. National and local developments are making a difference in New Zealand

Life expectancy for indigenous people in colonised countries is shorter than it should be. In New Zealand, Maori die on average 10 years younger than people of Anglo-European descent.1 The usual suspects of poverty and poor socioeconomic opportunities contribute to inequity, but failures in service organisation and delivery are part of the picture. New Zealand is not the only colonised nation with higher rates of illness and premature death, but it is making concerted efforts to address the disparity.

Enhancing responsiveness to cultural needs

The starting point in identifying inequality in health outcomes is ensuring accuracy of data. The 2001 census indicates that 14.1% of New Zealand's population is Maori, 6.2% Pacific people, and 6.4% Asian.2 Each of these groups is actually growing at a faster rate than pakeha (the white descendants of colonial settlers). Until recently, documentation of ethnic origin in relation to health was not routinely collected. Even when ethnic group was recorded, it tended to be based on health workers' assessments of the appearance of the service user. Addressing health needs and planning appropriate levels of service clearly require a more accurate and sensible approach. Self identification of ethnicity is now established as best practice in New Zealand1; as a result, knowledge about health and the incidence and prevalence of certain conditions is improving.

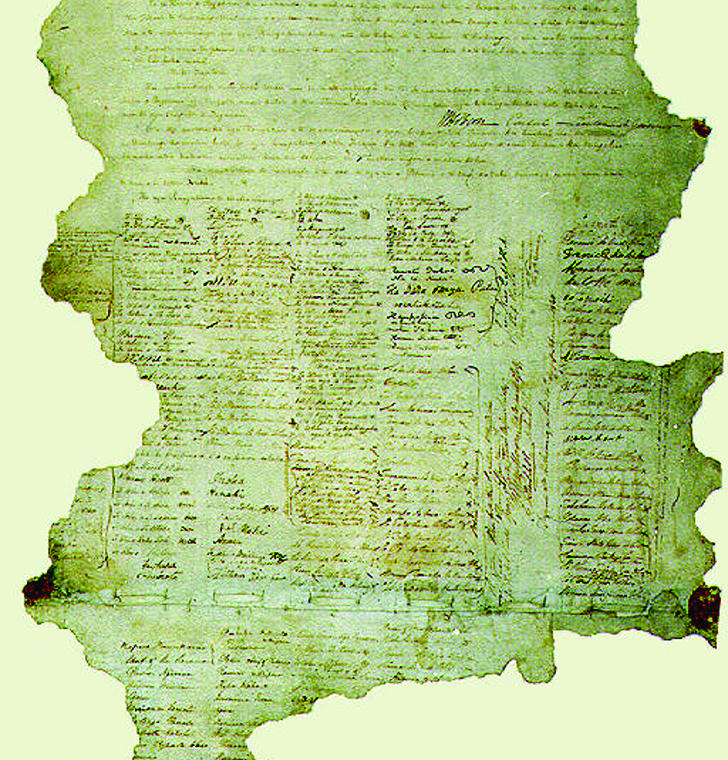

Figure 1.

The Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840 by about 500 Maori chiefs from around the country

Credit: ARCHIVES NEW ZEALAND

A second step in enhancing responsiveness to cultural needs of patients is “cultural safety,” introduced by Irihapeti Ramsden.3 Cultural safety goes further than learning factual information regarding dietary or religious needs of different ethnic groups: it means engaging with the sociopolitical context of beliefs about whanau (family) and of what is tapu (forbidden) in a range of healthcare practices from washing some-one, through to physical examination or handling of biological specimens. It is increasingly understood that failure to take such things into consideration may well lead to interventions that fail in the short term and that build suspicion in the longer term, as people lose their trust in healthcare providers. Although cultural safety began as a movement within nursing, it is now being introduced within other undergraduate curriculums and professional development programmes.

Developing services

Difficulties in accessing services have been identified for Maori and other ethnic groups in New Zealand.1 Delays in starting treatment may well contribute to the significantly worse outcomes found in stroke, cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and mental health.4-6 Services that utilise the principles of cultural safety can reduce barriers and encourage access, and a number of culturally specific services have been successfully introduced. Among developments are primary care services based within marae (local meeting houses), specialist outreach clinics for young people with mental health problems, and culturally specific health education programmes.1 Making decisions about where and when culturally specific services, rather than culturally safe generic services, are most appropriate is difficult and complex. It is likely that each is required if high quality services are to be provided across the country.

Developing appropriate and responsive services requires dialogue and partnership between health service organisers and community leaders. Partnership is a core component of the Treaty of Waitangi, the original agreement intended to protect the interests of both the original inhabitants and the incomers. The treaty has not always been honoured by the New Zealand government or pakeha, and examples of institutional and personal racism are well documented.7 Over the past few decades, the responsibilities of leadership have been challenged, and many steps have been taken towards redressing the lack of responsiveness to the treaty shown throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Experience from other countries indicates that without the treaty New Zealand may well not have tackled much of the implicit and explicit discriminatory practice. Things are by no means perfect, and without continued effort the improvements made so far may be transitory. However, healthcare policy, clinical practice, and research processes are now all influenced by the treaty, and attention to the impact of ethnicity on health is growing.

Whare Tapa Wha model of health

Taha Wairua (spiritual)—Capacity for faith and wider communion

Taha Hinengaro (mind)—Capacity to communicate, think, and feel

Taha Tinana (physical)—Capacity for physical growth and development

Taha Whanau (extended family)—Capacity to belong, to care, and to share

Summary points

Disparities in healthcare outcomes are linked to ethnicity

Self identification of ethnicity, “cultural safety,” and in New Zealand's case, attention to the Treaty of Waitangi, enhance responsiveness to cultural needs of patients

Services that are responsive can reduce barriers, encourage access, and improve outcomes for patients

Evaluating effectiveness of services

Most measures of process and outcome are based largely on Eurocentric or American perspectives.8 Though such approaches have a place, they may fail to address issues that matter most to people of different ethnic origin. A recent model explicitly addressing a Maori perspective of health and wellbeing is the Whare Tapa Wha model, visualised as a “four sided house” where each construct below is required for health (box). The link between these four components is fundamental: “A person's synergy relies on these foundations being secure. Move one of these, however slightly, and the person may become unwell.”9

Although derived by experts, this model is quite different from many others used in health care in that it is definitely owned by the community. It makes the interconnectedness between different aspects of life and wellbeing explicit, has been the basis of new services, and underpins an outcome measure now used in mental health.10

Life expectancy and poorer outcomes in association with ethnicity remain important issues for many countries, including New Zealand. National and local developments such as those described here are making a difference, but ongoing and expanding effort is required if major improvements in health are to occur.

Competing interests: None declared.

This paper appears also in Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12: 237-8

References

- 1.Ministry of Health, New Zealand. Reducing inequalities in health. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2002.

- 2.Statistics New Zealand. 2001 census of population and dwellings. www.stats.govt.nz/census (accessed 1 Aug 2003).

- 3.Ramsden, I. Cultural safety in nursing education in Aotearoa (New Zealand). Nursing Praxis in New Zealand 2003;8: 4-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNaughton H, Weatherall M, McPherson K, Taylor W, Harwood M. The comparability of community outcomes for European and non-European survivors off stroke in New Zealand. N Z Med J 2002;115: 98-100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sporle A, Pearce N, Davis P. Social class mortality differences in Maori and non-Maori men aged 15-64 during the last two decades. N Z Med J 2003;115: 127-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinded PM, Simpson AI, Laidlaw TM, Fairley N, Malcolm F. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in New Zealand prisons: a national study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2001;35: 166-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid P, Robson B, Jones C. Disparities in health; common myths and uncommon truths. Pacific Health Dialogue 2000;7: 38-48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McPherson KM, Brander PM, McNaughton H, Taylor W. Living with arthritis—what is important? Disabil Rehabil 2001;23: 706-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durie MH. Whaiora—Maori health development. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- 10.Kingi, TK, Durie MH. Hua oranga—a Maori measure of mental health outcome. Palmerston North: Massey University, School of Maori Studies, 2000.