Abstract

Monitoring describes the prospective supervision, observation, and testing of an ongoing process. The result of monitoring provides reassurance that the goal has been or will be achieved, or suggests changes that will allow it to be achieved. In therapeutics, most thought has been given to Therapeutic Drug Monitoring, that is, monitoring of drug concentrations to achieve benefit or avoid harm, or both. Patients and their clinicians can also monitor the progress of a disease, and adjust treatment accordingly, for example, to achieve optimum glycaemic control. Very little consideration has been given to the development of effective schemes for monitoring for the occurrence of adverse effects, such as biochemical or haematological disturbance. Significant harm may go undetected in controlled clinical trials. Even where harm is detected, published details of trials are usually insufficient to allow a practical monitoring scheme to be introduced. The result is that information available to prescribers, such as the Summary of Product Characteristics, frequently provides advice that is incomplete or impossible to follow. We discuss here the elements of logical schemes for monitoring for adverse drug reactions, and the possible contributions that computerized decision support can make. We should require evidence that if a monitoring scheme is proposed, it can be put into practice, will prove effective, and is affordable.

Keywords: computer decision support, drug therapy/adverse effects, medicines regulation, monitoring, prevention and control

Introduction

Monitoring is a process of checking a system that changes with time, in order to guide changes to the system that will maintain it or improve it. A recent article discussing the monitoring of disease in medicine has drawn attention to the more general problem of monitoring the health of patients suffering with chronic disease [1]. Monitoring has three components: proactive, targeted observation; analysis; and action. There are some obvious requirements for monitoring to achieve its aims. It should be clear from the outset of the process which observations are to be monitored. The observations have to reflect important characteristics of the system’s variation relative to the goal of monitoring, and be made with sufficient frequency and accuracy to capture important changes. The analysis of the observations has to define the changes that need to be made to the system to return it to a desirable state, or improve the chances of a desirable outcome. The actions should bring about those changes.

The oxygen saturation monitor, which sounds an alarm if the patient’s oxygen saturation drops below some threshold value, illustrates the process. The monitoring in this case is designed to improve the safety of the system by warning of a need to increase the concentration of oxygen in inspired air, so that the patient does not suffer from the consequences of hypoxia. The observations of oxygen saturation are made continuously and are reasonably accurate. The analysis, which consists of comparing the measured oxygen saturation with some preset warning value, is based on clinical experience. If the analysis is correct, then it is safe to maintain the current inspired oxygen concentration. If the alarm sounds, then action is required to improve oxygenation.

The monitoring of blood haemoglobin concentration in a patient known to have aplastic anaemia provides a related example. The monitoring is designed to ensure that there is sufficient haemoglobin for the patient to remain safe. If the concentration falls too low, then transfusion is required. Monitoring in this example is intermittent but remains reasonably accurate. The clinician has to estimate from experience how far the haemoglobin may drop before action is required. Provided the changes in haemoglobin concentration occur gradually, the blood testing is frequent enough, and the time to organize blood transfusion is not too long, then the patient should remain safe.

These examples illustrate monitoring by observing directly the quantity of interest, but indirect (surrogate or proxy) measures are also widely used. The choice of surrogate measure is important, as the surrogate needs to reflect closely the reaction of interest. Development of better surrogate measures to aid monitoring of disease and its response to therapy is dependent upon an understanding of the chain of events in the pathogenesis of disease through to its final clinical end-point [2]. An example of a surrogate measure is the measurement of carbon monoxide diffusing capacity of the lung to monitor whether amiodarone has caused lung fibrosis. This has been widely used and is recommended in drug information literature. However, it may not be useful: a prospective study failed to determine the changes in diffusing capacity that warranted discontinuation of amiodarone treatment to prevent incipient pulmonary toxicity [3].

In all these examples of continuous or discontinuous measurement, and direct or surrogate observations, the action to take is determined by a single threshold value. Provided the observation remains on one side of the threshold, no action is required. Once the threshold is crossed, it is necessary to act at once. In other circumstances, there is a ‘safe range’ and an upper and lower threshold. While the results of observations, for example, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) or platelet count, are within the safe range, no action is taken. Actions are required if the upper or lower threshold values are passed, and the actions are usually different. In more complex systems, there may a continuous response to the observed measurement. Patients being given insulin by infusion have their blood sugar measured frequently to adjust the insulin infusion requirement every hour or so, whereas adjusting diabetic therapy based on HbA1c occurs less frequently over weeks to months.

Monitoring in therapeutics

Monitoring in the sense described is used in three different aspects of the therapeutic process. Clinicians, and patients themselves, can monitor response to treatment of a specific condition – for example, monitoring the temperature during antibacterial treatment. If a drug has a narrow therapeutic range, samples can be taken to allow the dose to be adjusted so that the concentration remains between a minimum value for efficacy and a maximum value for safety. This ‘therapeutic drug monitoring’ (TDM) has been widely used to adjust dosages of antiepileptic drugs such as phenytoin [4]. Although TDM is usually restricted to monitoring of drug concentrations, similar monitoring schemes that aim to maintain effects in a desirable range between upper and lower bounds are also common. Examples include testing capillary blood glucose concentration during insulin treatment and testing blood clotting times during warfarin therapy. An early example of systematic monitoring to ensure that treatment was within a therapeutic range was the measurement of ankle reflex time as a surrogate for thyroid status [5].

Monitoring is often advocated as a way of avoiding or mitigating the harm from adverse drug reactions [6]. Monitoring for adverse effects by repeated laboratory testing seems to have begun with the observation that the antibacterial drug chloramphenicol could cause bone-marrow toxicity of two types, one of which occurred at high dosage and was reversible, and the other of which could occur at any therapeutic dosage and generally resulted in fatal aplastic anaemia [7]. The view persists that ‘It is . . . advisable to perform blood tests in the case of prolonged or repeated administration. Evidence of any detrimental effect on blood elements is an indication to discontinue therapy immediately’[8].

It transpired that monitoring by testing the full blood count periodically could give warning of the relatively benign form, but not the fatal form of chloramphenicol-induced bone-marrow failure [9]. There are two possible reasons for this. First, the process, once begun, is irreversible, so that, however sensitive the method of detection of early change, it will be too late. Second, the process may be so rapid that no realistic monitoring frequency will allow its detection.

There is often a trade-off between the rarity of the adverse reaction, which reduces the value of monitoring (i) by making detection rare and (ii) by increasing the proportion of false-positive results, and the seriousness of the reaction, which makes finding each case increasingly worthwhile. It is therefore unlikely to be cost-effective to introduce a monitoring scheme for a rare adverse reaction of little consequence, but very cost-effective to introduce one for a common and serious adverse reaction, assuming the other criteria are fulfilled.

The advice on haematological monitoring given to prescribers might be expected to reflect difficulties such as these, noted over 25 years ago. However, many Summaries of Product Characteristics provide instructions for monitoring for haematological adverse reactions that are incomplete or impractical in modern clinical settings [10].

The incidence of hyperkalaemia in patients treated with spironolactone for heart failure seems much greater in practice than in the randomized controlled trial that showed the value of the treatment [11, 12]. This seems unlikely to be simply a problem of monitoring. In general terms, patients in clinical practice are sicker and less frequently reviewed than in clinical trials and therefore it is not surprising that in many examples the rate of adverse effects is higher in actual use when compared with the rates seen in the trials. Real patients may also be less likely to adhere to a stringent monitoring scheme, or more likely to have concurrent ill health that increases the chances of finding an abnormal result that is not due to the adverse reaction, or older than trial patients, and perhaps as a consequence more rapidly susceptible to the adverse drug reaction, so that the time between a reaction first being observable and it causing irreversible damage may be shorter. It raises the question of how to devise safe monitoring schemes that will remain effective when treatments move from clinical trials to general use.

Literature reports of controlled clinical trials of therapeutic drugs are generally poor at reporting harm from adverse effects, and even when patients have been monitored for adverse effects during the trials, details may be insufficient to allow a practical monitoring scheme to be introduced. Recent recommendations from the CONSORT group [13] should improve the reporting of harms, but are unlikely to ensure that monitoring schemes are rational and evidence based. These and other difficulties have led us to consider what might be required for a successful monitoring scheme to prevent harm from adverse drug reactions in individual patients.

Systems, control theory and feedback

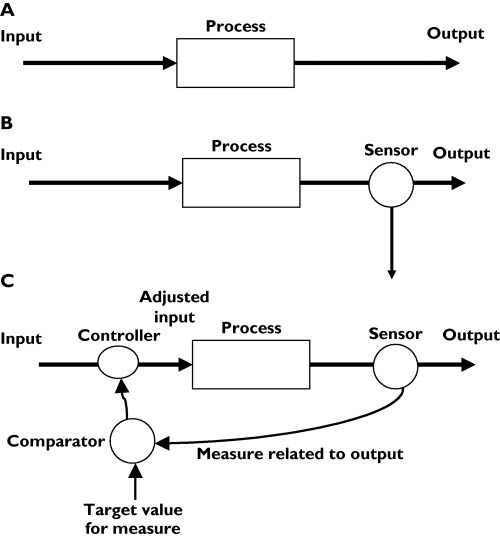

A ‘system’ has an input, which is transformed by the process of the system to an output (Figure 1a). The output may have a desired value. If the output is measured, the input can be altered so that the output approaches the target (Figure 1b). The output can be observed empirically, for example, by giving intravenous furosemide until basal inspiratory crackles disappear. Sometimes the output can be calculated if the input and the properties of the system are known, as with intravenous iron replacement therapy; and sometimes the output can be used to adjust the input automatically, as with patient-controlled analgesia. In such systems, there is ‘feedback’ between the output and the input (Figure 1c). In other words, the system acts to vary the input according to the value of the output in such a way that the output approaches or maintains the desired value.

Figure 1.

Systems, monitoring, and feedback. (A) A simple system, in which a process changes an input to an output. (B) A simple system with monitoring of the output. (C) A system with feedback control of the input to maintain the desired output

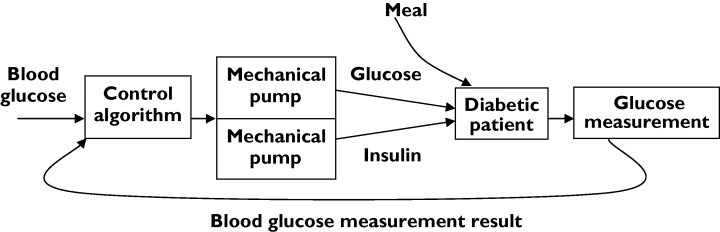

Clinicians have sometimes been able to use control theory explicitly. An example is the ‘artificial pancreas’ (Biostator®) [14], used to measure blood glucose concentration continuously and to infuse glucose or insulin solution at a rate that will maintain blood glucose concentration constant at some preset target (Figure 2). A more widely seen, but less perfect, example is patient-controlled analgesia, in which a patient can press a button that activates a morphine pump, resulting in pain relief. Excessive morphine causes drowsiness and drowsiness inhibits the patient from pressing the button again. (There are additional safeguards.)

Figure 2.

The principles of the Biostator®, a machine to regulate blood glucose concentration

The simplest analysis of physical control systems assumes that a given input will always produce the same output, that the output is measured continuously and without error, and that the system remains stable over time. Much more complex analysis is possible. Control theory has been extended to systems in which random noise can influence input or output or both; in which measurements can be made from time to time rather than continuously; and where the system’s properties change over time.

Statistical process control

A system that is ‘in control’ will have an output that remains stable within a defined range around the target value. In a system with no appreciable random error in measured output, this can be established directly by measuring the output. Where there is significant random error in the output or in its measurement, then statistical methods are required to demonstrate whether the system is likely to be ‘in control’. During the 20th century, Shewhart and others introduced a series of simple graphical methods for this purpose [15]. These were originally employed in the context of industrial processes such as the manufacture of rivets to a given tolerance, but have wider applications. Medical examples often revolve around quality improvement; there are some clear examples relating to doctors’ performance and work flow [15, 16]. There are fewer examples relating to physiological, biochemical and other clinical variables, but control charts are well suited to this purpose.

Monitoring for adverse effects can revolve around measurements that are made on continuous variables. If these are surrogates for clinically relevant adverse outcomes, rather than the outcomes of interest, a decision needs to be made regarding risks of continuing treatment if the surrogate variable changes. Decision-making can be simplified by the use of rules and many schemata have been used related to the inputs and outputs of therapeutic systems. Consider, for example, the change in liver function tests in a patient treated with antituberculous chemotherapy. The clinician and the patient wish to avoid acute liver failure. Periodic tests are made of serum transaminase activity. Guidelines recommend that treatment be stopped if transaminase activity exceeds three times the upper limit of normal [17]. The guidelines do not specify how often transaminase activity should be measured, nor the predictive value of the rule. The guidelines fail to provide systematic instructions for monitoring (Ferner et al.[10]) and fail to provide the information required for the patient and clinician to weigh rationally the benefits and harms of treatment.

Computerized decision support systems

Many systems exist for computerized prescribing and for electronic medicines management. Clinical care can produce a huge volume of data and computers are ideal for collecting the information and performing the repetitive analyses required within monitoring systems. If the program includes some simple rules or algorithms, then it can help physicians make decisions regarding treatment. These principles have been studied with respect to TDM. A Cochrane review identified six studies showing that computerized dosage support can reduce unwanted effects of treatment with drugs such as digoxin [18].

Some electronic prescribing systems already use informatics in decision-making [19]. They range from systems that warn prescribers of drug–drug interactions to those that involve many levels of care and inputs from many sources. Decision support can be incorporated into computer systems, for example to interpret changes in drug concentrations or trends in haematological parameters that may indicate adverse effects. There is a clear difference between systems that can identify clinical alerts (e.g. raised serum creatinine concentration) or provide prompts to clinicians to perform simple tests at preset intervals, and those that correlate changes in some observation to alterations in the type or dose of prescribed drug. Computer-aided analysis has been used in the TDM of aminoglycoside antibiotics to detect unexpected changes in aminoglycoside concentration or rising serum creatinine concentration, and so support clinical decision-making [20]. Such programs can take into account complex information, including many patient variables and coprescription of interacting drugs.

Neural networks are computational systems that attempt to simulate the neurological processing abilities of biological systems by having many interconnected units that measure simple attributes. When they are ‘taught’ about particular patterns, neural networks are able to ‘learn’ what combinations of system attributes are associated with a particular feature. This allows them to distinguish between a system with that feature and a system without that feature. They can be programmed to recognize, for example, particular faces from digitized images shown in various orientations. They have the potential to create simplicity from complexity in clinical settings and, for example, are able to model complex pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic systems. Their ability to emulate a multivariable system, and to be trained, means that they are potentially valuable for monitoring the effects of drugs in the human body. A neural network may store information about past case experiences (e.g. clinical patterns and drug dosage regimens) and, once properly trained, will have the structure within the net and the proportional strengths betweens the neurones involved to allow additional inputs to feed into and propagate through the network, thus giving rise to a derived output. This approach has been used experimentally to predict delayed graft function in renal transplant patients treated with ciclosporin more accurately than other methods [21]. They have also been used to analyse a large database of reports of adverse drug reactions, where events are linked to a drug suspected of causing them [22]. They do not seem to have been used clinically to help monitor individual patients during treatment, although complex Bayesian modelling of drug concentrations, for example [23], might make good use of them.

The optimal distribution of observations in monitoring for adverse reactions

Continuous measurement is rarely practical in monitoring for adverse drug reactions, and observations and laboratory tests have to be undertaken from time to time.

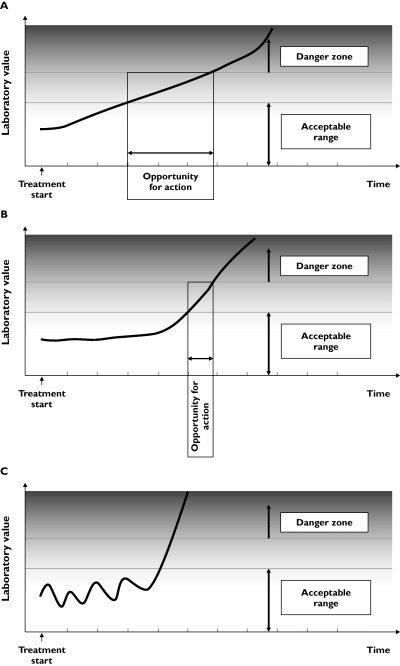

Figure 3a shows a simple case, where there is no error, the threshold for action is well defined, and the variable of interest changes linearly with time from the start of treatment, with no lag. Any observation made within the time range labelled ‘opportunity for action’ will detect a value outside the acceptable time range before there is a danger of harm. The earliest time is at the left-hand margin, and the latest at the right-hand margin of the time period labelled ‘opportunity for action’. With another patient, whose response to the adverse effect of the drug is slower, the trajectory might be different (Figure 3b). It is recommended that patients receiving heparin have platelet counts checked to detect antibody-mediated thrombocytopenia, the earliest time of which is usually about 5 days; the trajectory thereafter is less clear.

Figure 3.

The opportunities for action when a monitored variable changes. (A) The change in the monitored variable is linear with time, and there is no lag. (B) The change in the monitored variable is linear with time, but starts after a lag. (C) The change in the monitored variable is chaotic.

To be effective, a monitoring scheme would have to ensure that, for any member of the population exposed, observations were always made between the earliest time that a deviation is apparent and the latest time before danger is imminent.

It might be possible to deduce from repeated observations the likely trajectory of the results under study. This will be easiest when observations are stable prior to treatment and change linearly with time, without lag, after treatment. There will be increasing difficulties if the trajectory is curvilinear, or chaotic, or catastrophic. In the last case, if there is no premonitory change and the adverse effect occurs rapidly, monitoring will not be useful (Figure 3c).

Random variation will introduce complexity into any analytical scheme of this sort, even if the time-dependence of the monitored variable is known and even if the underlying trajectory is linear. There will be variation (i) in the true value for an individual over time (e.g. diurnal variation), (ii) as a result of measurement error, (c) in the threshold and danger cut-off values for the population, and (iv) in these values for the particular individual.

Practical consequences

The practical consequences of this discussion are that strategies for monitoring are dependent upon many different variables and will be easier and more successful in some circumstances than in others (Table 1). We have previously described how the time-course from the start of treatment is one of the important characteristics of an adverse drug reaction, and several different forms of time dependence are recognized [24]. For some adverse drug reactions there is a very good chance that a practical monitoring scheme will detect a reaction before too much harm is done. For others, however, there is little or no hope that this will be so. Since there has been very little systematic study of the problem, most of the advice on monitoring is based on empirical observation or, more often, on supposition. We propose that advice on monitoring should be tested against the criteria that we have previously described [6], to ensure that there is some prospect of it being successful without consuming unjustifiably large resources.

Table 1.

The factors influencing opportunities for monitoring adverse drug reactions

| Implementing a monitoring scheme will be easier when: | Implementing a monitoring scheme will be harder when: |

|---|---|

| The variable is directly relevant to system | The variable is of uncertain relevance to the system |

| The variable is linear with time | The variable is nonlinear |

| The variable changes slowly | The variable changes rapidly |

| Changes are sensitive to potential harm | Changes are insensitive to potential harm |

| Changes are specific for potential harm | Changes are nonspecific |

| Monitoring is continuous | Monitoring is discontinuous |

| Monitoring is error-free | Monitoring is error-prone |

| The threshold for any action is well-defined | One or more of the action thresholds is ill-defined |

| Analysis of the output of monitoring is straightforward | Analysis of the output of monitoring is complex |

| The optimum action is obvious | The optimum action to take is undefined |

| The process is cheap | The process is expensive |

A practical method for establishing the correct interval for monitoring, or whether monitoring is possible at all, would be to monitor the variable of interest in a representative group of patients as frequently as is possible in the real world. For example, it might be possible in a group of patients recruited to a study to have blood taken once a week over a period of several months. The number of adverse events observed will depend on the number of subjects, the underlying frequency of the reaction in those subjects and, for some adverse effects, the dose of drug and the duration of the study. Provided the number of events is sufficiently high, the study should establish how sensitive and specific the test variable is in detecting the adverse effect, in the ‘ideal’ circumstance of frequent monitoring. Statistical analysis of prespecified subsets of the data (e.g. sets of results of one blood test in four, that is, one every month) would then permit a comparison between the most intensive practical monitoring scheme and less intensive schemes. In this way, a reasonable basis for systematic instructions for monitoring could be established [25].

There is a marked difference between a theoretically ideal scheme and one that works in practice in the real world. There is no hope, however, of approaching a reasonably useful scheme if it proves impossible to monitor effectively even in the controlled environment of a clinical trial. If a scheme does appear feasible, then focusing efforts on real-life problems may help guide the appropriate use of resources to enhance patient safety rather than cost health services or drug companies large amounts of money using the ad hoc and often inappropriate guidance available at present.

Until studies have been undertaken to demonstrate that monitoring schemes can be put into practice, are effective, and are affordable, we should be very sceptical of advice – present in over half of all drug Summaries of Product Characteristics – to monitor for adverse (or beneficial) effects. The time has come for evidence-based monitoring of adverse drug reactions.

We are very grateful to Professor Paul Glasziou for helpful discussion.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Glasziou P, Irwig L, Mant D. Monitoring in chronic disease: a rational approach. BMJ. 2005;330:644–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7492.644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson JK. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:491–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gleadhill IC, Wise RA, Schonfeld SA, Scott PP, Guarnieri T, Levine JH, Griffith LS, Veltri EP. Serial lung function testing in patients treated with amiodarone: a prospective study. Am J Med. 1989;86:4–10. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)90221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reynolds DJ, Aronson JK. ABC of monitoring drug therapy. Making the most of plasma drug concentration measurements. BMJ. 1993;306:48–51. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6869.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miles DW, Surveyor I. Role of the ankle-jerk in the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease. BMJ. 1965;I:158–61. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5428.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pirmohamed M, Ferner RE. Monitoring drug treatment. BMJ. 2003;327:1179–81. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anonymous. Chloramphenicol toxicity. Lancet. 1969;2(7618):476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Summary of Product Characteristics for Kemicetine Succinate Injection Available at: http://emc.medicines.org.uk/

- 9.Horler AR. Blood disorders. In: Davies DM, editor. Textbook of Adverse Drug Reactions. 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferner RE, Coleman J, Pirmohamed M, Constable S, Rouse A. The quality of information on monitoring for haematological adverse drug reactions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60:448–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anton C, Cox AR, Watson RDS, Ferner RE. The safety of spironolactone treatment in patients with heart failure. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2003;28:285–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2003.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Lee DS, Kopp A, Austin PC, Laupacis A, Redelmeier DA. Rates of hyperkalemia after publication of the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:543–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ioannidis JPA, Evans SJW, Gotzsche PC, O’Neill RT, Altman DG, Schulz K, Moher D for the CONSORT group. Better reporting of harms in randomized trials. An extension of the CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:781–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fogt EJ, Dodd LM, Jenning EM, Clemens AH. Development and evaluation of a glucose analyzer for a glucose controlled insulin infusion system (Biostator) Clin Chem. 1978;24:1366–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohammed MA, Cheng KK, Rouse A, Marshall T. Bristol, Shipman, and clinical governance: Shewhart’s forgotten lessons. Lancet. 2001;357:463–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical process control as a tool for research and healthcare improvement. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:458–64. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.6.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joint Tuberculosis Committee of the British Thoracic Society. Chemotherapy and management of tuberculosis in the United Kingdom: recommendations 1998. Thorax. 1998;53:536–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walton RT, Harvey E, Dovey S, Freemantle N. Computerised advice on drug dosage to improve prescribing practice. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002894. Issue 1, Art, no. CD002894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anton C, Nightingale PG, Adu D, Lipkin G, Ferner RE. Improving prescribing using a rule based prescribing system. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:186–90. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.006882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lenert LA, Klostermann H, Coleman RW, Lurie J, Blaschke TF. Practical computer-assisted dosing for aminoglycoside antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1230–5. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.6.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brier ME, Aronoff GR. Application of artificial neural networks to clinical pharmacology. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;34:510–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coulter DM, Bate A, Meyboom RH, Lindquist M, Edwards IR. Antipsychotic drugs and heart muscle disorder in international pharmacovigilance: data mining study. BMJ. 2001;322:1207–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7296.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tod MM, Padoin C, Petitjean O. Individualising aminoglycoside dosage regimens after therapeutic drug monitoring: simple or complex pharmacokinetic methods? Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40:803–14. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140110-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aronson JK, Ferner RE. Joining the DoTS: new approach to classifying adverse drug reactions. BMJ. 2003;327:1222–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferner RE, Coleman JJ, Anton C, Watson RDS. Protocol Submission: Preventing Serious Hyperkalaemia in Heart Failure Patients Treated with Spironolactone by Frequent Monitoring. London: NHS Central Office for Research Committees; 2005. [Google Scholar]