Abstract

Aims

Carbamazepine (CBZ) is an inducer of cytochrome P450 enzymes, which have been implicated in many drug interactions. However, for immunosuppressant and anti-HIV drugs, whose main site of action is the lymphocyte, induction of P-glycoprotein (Pgp) may also be important. In this study, we have investigated whether CBZ acts as an inducer of Pgp in lymphocytes.

Methods

Pgp expression was assessed by flow cytometry and real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction using lymphocytes from four healthy subjects after incubation with therapeutic concentrations of CBZ, using rifampicin as a positive control. Binding to DR-4 elements in the MDR1 promoter was assessed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and a luciferase-reporter construct.

Results

CBZ increased MDR1 mRNA expression at 6 h by 3.7-fold [95% confidence interval (CI) 0, 7.6) when compared with controls. CBZ increased lymphocyte Pgp expression at 72 h by 7.6-fold (95% CI 2.1, 13.2) over control values. EMSA revealed a 2.1-fold (95% CI 1.5, 2.7) increased binding to the DR-4 element of CBZ when compared with control values. Activation of the DR-4 element was confirmed using reporter constructs. Rifampicin also had similar effects in all experiments.

Conclusions

Carbamazepine induces Pgp in a manner comparable to rifampicin, by increasing binding to the DR4 element. This has implications for interactions involving drugs whose site of action is the lymphocyte.

Keywords: carbamazepine, induction, P-glycoprotein, PXR, rifampicin

Introduction

P-glycoprotein (Pgp) is an ATP-dependent drug efflux pump with a wide substrate specificity. Pgp decreases the intracellular accumulation of a number of drugs including antiretroviral agents and cyclosporin [1–4], which has clinical implications where the lymphocyte is the site of action of the drug.

Carbamazepine (CBZ) is a widely used anticonvulsant [5], which may be taken for many years. CBZ induces hepatic CYP3A4, which is the basis for clinically significant drug–drug interactions [6]. CBZ also induces Pgp in intestinal cell lines [7], and a recent study demonstrated induction of intestinal MDR1 (the gene expressing Pgp; also known as ABCB1) mRNA with an associated increase in the clearance of talinolol [8]. Furthermore, in patients who are resistant to treatment with anticonvulsants, over-expression of Pgp has been demonstrated in surgically resected specimens [9–11]. This abnormal pattern of Pgp expression has been postulated to be a function of the disease state, but it could also potentially be a consequence of chronic drug therapy.

Accordingly, the aim of this study was to determine whether CBZ induces Pgp expression in peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBMC) and to define the possible mechanisms of induction. The PBMC has been advocated as a model tissue for studying the modulation of Pgp activity by drugs [12]. Given the chronic and increasing use of CBZ in a number of diseases including epilepsy, trigeminal neuralgia and depression, induction of Pgp in lymphocytes may be an important reason for therapeutic failure with drugs such as cyclosporin, whose main site of action is the lymphocyte.

Methods

Materials

Rifampicin (RIF), CBZ and dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) were obtained from Sigma (Poole, UK), Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) from Gibco BRL (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) and Cell Fix from Becton Dickinson (Oxford, UK). All real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reagents were from Roche Diagnostics Ltd (Lewes, UK). Unless otherwise stated, antibodies for flow cytometry were purchased from Serotec Ltd (Oxford, UK) and all oligonucleotides (including primers) were from Sigma Genosys Ltd (Cambridge, UK). Monoclonal antibody UIC2 was obtained from Coulter Immunotech (Marseilles, France).

Cell incubation conditions

PBMC were isolated from four healthy caucasians (three male and one female) and handled as previously described [13]. The subjects, each of whom gave verbal consent, were in good health and receiving no concomitant medication. Variable densities of PBMC were incubated with therapeutic concentrations of CBZ (50 µm), RIF (25 µm) or vehicle alone (DMSO). For the analysis of Pgp protein expression, cells were incubated for 24, 48 and 72 h in order to establish the optimum conditions. For RNA studies, the cells were incubated for 6 h [as defined by a time course study using standard block reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR; data not shown], whereas for the electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA), the cells were incubated for 1 h (estimated from mRNA data).

Analysis of Pgp expression

Flow cytometric analysis of Pgp expression was carried out as described previously using the monoclonal antibody UIC2 [13]. This antibody has not been reported to cross-react with any other proteins. The fluorescence of the cells was plotted against the number of events and the data were registered on a logarithmic scale followed by calculation of the median fluorescence. Observations were confirmed by Western blotting of whole cell homogenates using the monoclonal antibody C219 as described previously [14]. This antibody has previously been shown to cross-react with MDR3 (ABCB4).

Quantification of MDR1 mRNA by real-time RT-PCR

Total cellular mRNA was isolated and cDNA synthesis conducted using methodology that is established within our laboratory [15–17]. Quantification of MDR1 mRNA was achieved by real-time PCR using the Roche lightcycler. Briefly, 100 ng of cDNA was combined with MgCl2 (4 µm), sense (AAGCGACTGAATGT TCAGTG) and antisense primers (AGAGCTGAGTTC CTTTGTCT; 0.4 µm each) and CYBR green (2 µl) in a final volume of 10 µl. Amplification was carried out for 40 cycles with an annealing temperature of 56°C. A standard curve was constructed alongside the samples in the range of 104−109 copies of the MDR1 amplicon per reaction. This method was rigorously validated in a previous study [17].

Assessment of binding to the MDR1 putative DR-4 binding domain by EMSA

DNA binding activity was determined by the EMSA using a radiolabelled DR-4 consensus oligonucleotide. The double-stranded oligonucleotide containing the consensus DR-4 binding site (identified by Geick et al. [7]) consisted of the following sequence:

5′-GATCCTCATTGAACTAACTTGACCTTGCTCCA-3′

The double-stranded oligonucleotide, with mutations underlined, used for noncompetitive inhibition (mutated oligo) of binding, consisted of the following sequence: 5′-GATCCTCATTGTTCTAACTTGTTCTTGCTCCA-3′. Nuclear protein (10 µg) was incubated at room temperature for 10 min with gel shift binding buffer [50 mm Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 250 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 2.5 mm EDTA, 2.5 mm DTT, 20% glycerol, 0.2 mg ml−1 poly(dI-dC).poly(dI-dC)]. To assess the specificity of binding to the labelled oligonucleotide, an excess of either unlabelled DR-4 or mutated DR-4 oligonucleotide (1× and 5× labelled probe) was added to the control reactions. All other EMSA methods were as described previously [18].

Culture of CCRF-CEM lymphoblastoid cells, transfection of DR-4+/– MDR1 reporter plasmids and reporter assays

The human lymphoblast cell line, CCRF-CEM [19], was used in the reporter studies. One day before transfection, 4 × 105 cells per well were plated in 24-well plates. Reporter gene plasmids (0.25 µg; containing either 8055 bp or 7771 bp upstream of the MDR1 transcription start site) and 0.1 µg of pSV-β-galactosidase control vector were introduced into the cells using 0.75 µl of GeneJuice® transfection reagent. Five hours after transfection, the cells were split into 96-well plates for drug incubations. The cells were then incubated for 40 h with 25 µm RIF, 50 µm CBZ or DMSO alone, prior to three washes with HBSS and lysis with the Promega reporter lysis buffer. After centrifugation, the cleared lysates were used for reporter gene assays. Luciferase measurements were carried out using the Promega Bright-Glo™ luciferase Assay System, and β-galactosidase assays using the Promega β-galactosidase enzyme assay system. Luciferase activity was then normalized with respect to transfection efficiencies using the corresponding β-galactosidase activity. This procedure was repeated for six separate transfections.

Statistical analysis

All results are presented graphically as mean ± SEM. Data were log transformed prior to statistical analysis using a paired t-test. Unless indicated, statistical analyses were performed on at least four replicate experiments, with a two-tailed P-value < 0.05 indicating significance.

Results

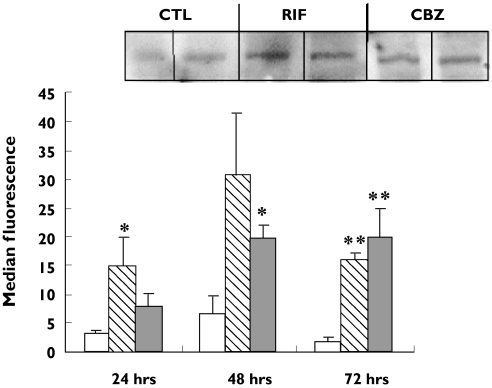

An increase in Pgp expression on PBMC was observed after 24 h incubation with both CBZ (50 µm) and RIF (25 µm). However, statistical significance for CBZ (14.5 ± 5.0; P < 0.05; 95% CI for the difference −19.9, −5.0) and RIF (15.9 ± 2.8; P < 0.005; 95% CI for the difference −18.6, −9.0) compared with control incubations (2.0 ± 0.7) was not observed until 72 h (Figure 1). The increase in Pgp expression was seen in lymphocytes from all four individuals and results were confirmed by Western blotting of whole-cell homogenates (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Expression of P-glycoprotein on peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBMC) measured by flow cytometry with the UIC2 primary antibody. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4 experiments). Statistical analysis was carried out on log-transformed data using a paired t-test. Significant induction was observed for rifampicin (RIF ( )) at 24 h, carbamazepine (CBZ (

)) at 24 h, carbamazepine (CBZ ( )) at 48 h and for RIF and CBZ at 72 h: *P< 0.05; **P< 0.01; ***P< 0.001. Inset: representative Western blot analysis of P-glycoprotein in PBMC treated with RIF and CBZ for 72 h. Control incubation (CTL) (□)

)) at 48 h and for RIF and CBZ at 72 h: *P< 0.05; **P< 0.01; ***P< 0.001. Inset: representative Western blot analysis of P-glycoprotein in PBMC treated with RIF and CBZ for 72 h. Control incubation (CTL) (□)

PBMC MDR1 mRNA expression was quantified by standard RT-PCR following treatment with CBZ and RIF for 2, 6 and 20 h. Induction of MDR1 was observed for both compounds (data not shown) and 6 h was selected for further real-time RT-PCR-based studies. PBMC MDR1 mRNA concentrations were quantified by real-time RT-PCR using mRNA isolated from the lymphocytes of the same four individuals. Induction of MDR1 mRNA was observed for both CBZ (17 743 ± 3369 copies per 100 ng cDNA; P < 0.01; 95% CI for the difference −19 975, −3346) and RIF (12 082 ± 4387 copies per 100 ng cDNA; P < 0.01; 95% CI for the difference −29 130, −6924) when compared with controls (6083 ± 1615 copies per 100 ng cDNA).

Binding to the putative DR-4 sequence in the MDR1 regulatory sequence was assessed by EMSA. An increase in binding was observed when radiolabelled probe was incubated with nuclear protein from PBMC treated with RIF (262 418 ± 15 990; P < 0.0001; 95% CI for the difference −121 004, −82 505) and CBZ (338 990 ± 64 947; P < 0.005; 95% CI for the difference −277 899, −78 754) compared with controls (160 664 ± 8282). Competition experiments with the corresponding unlabelled wild-type and mutated oligonucleotides confirmed the specificity of the binding (data not shown).

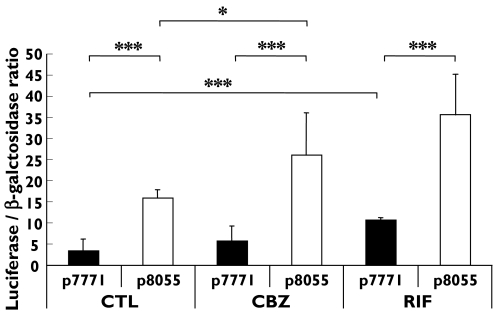

Functional activation of the MDR1 DR-4 regulatory sequence was assessed by using CEM cells transfected with luciferase constructs with and without this PXR binding site (Figure 2). A significantly higher activation of the p8055 transfectant was observed in response to RIF and CBZ when compared with the vehicle, consistent with activation of the DR-4 response element by these drugs. Furthermore, increased activation of the p7771 transfectant was also observed for rifampicin, indicating that sequences other than the DR-4 were also activated. Finally, in control samples the p8055 transfectants were activated to a greater extent than the p7771 transfectants, suggesting constitutive activation of these sequences.

Figure 2.

Effect of rifampicin (RIF) and carbamazepine (CBZ) on activation of luciferase activity in CCR-CEM cells transfected with p8055 (containing the putative MDR1 DR-4 motif) and p7771 (p8055 with the DR-4 motif absent). Data are presented as mean ± SD of six transfections. Statistical analysis was carried out using a paired t-test and found to be significant for RIF and CBZ: *P< 0.05; ***P< 0.001

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine whether CBZ, a widely used anticonvulsant, which is a known inducer of various cytochrome P450 enzymes, also induced Pgp in PBMC. Our data clearly show that CBZ caused an increase in Pgp expression, which was first observed after 24 h and continued until 72 h. This is consistent with the known slow onset of induction of cytochrome P450 enzymes that occurs with CBZ in vivo[20]. A criticism of our study is that only a small number of individuals were investigated. However, the purpose of the study was to demonstrate induction, and not to investigate variability in induction. Furthermore, our findings are in accordance with the demonstration that CBZ can induce Pgp in intestinal tissue [7, 8]. In the present work, induction of Pgp in PBMC was preceded on exposure to CBZ by a threefold increase in MDR1 mRNA concentrations, indicating that Pgp induction is at least in part due to increased transcription and/or mRNA stabilization. Induction was also observed on incubation of the PBMC with RIF, which was used as a positive control. Western blotting was also utilized, to assess induction within the whole cell, since Pgp is expressed in a number of intracellular compartments including the nuclear membrane [21] and the Golgi apparatus [22].

In order to delineate further the mechanism of induction of Pgp by CBZ, we also investigated its effects on the nuclear hormone response elements in MDR1. Identification of PXR-activated response elements in the MDR1 regulatory sequence [23] has spurred further work showing that the PXR-RXR heterodimer is important for the induction of Pgp by RIF [7, 24] through binding to the DR-4 response element. Our results show that CBZ and RIF increased binding to a consensus DR-4 response element in the promoter region of the MDRI and led to activation of these sequences in a reporter system. This indicates that PXR is also involved in induction of MDR1 in PBMC. In accordance with this, we have recently demonstrated the presence of PXR mRNA in lymphocytes [16]. PXR activation thus seems to be a common mechanism for induction in different tissues, protecting cells from toxic exogenous and endogenous chemicals through induction of drug-metabolizing enzyme and drug-transporter genes [25]. However, it can be seen in Figure 2 that the p7771 construct (lacking the DR-4) was also activated by RIF, indicating that factors other than PXR are involved in induction of MDR1 in response to this drug. Indeed, this region of the promoter has been shown to contain binding sites for many other transporters (reviewed in [26]).

There are two clinical implications of these findings. The first is the possibility of drug–drug interactions occurring through induction of Pgp. Both CBZ and RIF are potent inducers of CYP3A4 [27]. Our results, taken together with other reports [27–30], suggest that induction of Pgp plays a role in the interactions that have been described between CBZ and RIF, and other drugs such as the protease inhibitors and cyclosporin. It also provides a rationale for interactions with drugs such as digoxin, which are not CYP3A4 substrates, but are substrates for Pgp [31, 32]. We have recently shown that the effect of cyclosporin on lymphocyte proliferation was influenced by Pgp expression [33]. In vivo induction of Pgp in lymphocytes has also been observed after oral administration of RIF [34], and oral CBZ administration can result in the induction of other proteins in lymphocytes [35]. Whether CBZ can induce Pgp in lymphocytes in vivo will require investigation in a cohort of patients followed up longitudinally after commencement of the drug.

The second clinical implication of the data relates to the role of Pgp in mediating drug resistance in epilepsy. Over-expression of Pgp has been shown in brain tissue from refractory epileptics [9–11, 35]. Our data suggest that CBZ may be partly responsible for this induction of Pgp in brain, along with seizure activity [36]. However, extrapolation of our results depends on the validity of using lymphocytes as surrogates, and this needs to be demonstrated in the blood–brain barrier. Phenytoin and phenobarbitone are also known to activate PXR [37] and phenytoin has also recently been shown to induce Pgp [38]. Thus, such induction seems to be a common property of the aromatic anticonvulsant drugs.

In summary, our data show that CBZ, in a similar fashion to the known Pgp inducer RIF, induces both MDR1 mRNA and its protein product Pgp in PBMC. This induction seems to be mediated by the DR-4 response element in the regulatory region of the MDR1 gene. This induction may have implications for drug–drug interactions, and for the mechanisms of drug resistance in epilepsy.

Acknowledgments

The support of Pfizer Global Research and Development is gratefully acknowledged. The authors thank Dr O. Burke and Prof. M. Eichelbaum for contributing plasmids for the transfection assays utilized in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Kim RB, Fromm MF, Wandel C, Leake B, Wood AJ, Roden DM, Wilkinson GR. The drug transporter P-glycoprotein limits oral absorption and brain entry of HIV-1 protease inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:289–94. doi: 10.1172/JCI1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochman JH, Chiba M, Nishime J, Yamazaki M, Lin JH. Influence of P-glycoprotein on the transport and metabolism of indinavir in Caco-2 cells expressing cytochrome P-450 3A4. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:310–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glynn SL, Yazdanian M. In vitro blood–brain barrier permeability of nevirapine compared to other HIV antiretroviral agents. J Pharm Sci. 1998;87:306–10. doi: 10.1021/js970291i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwei GY, Alvaro RF, Chen Q, Jenkins HJ, Hop CE, Keohane CA, Ly VT, Strauss JR, Wang RW, Wang Z, Pippert TR, Umbenhauer DR. Disposition of ivermectin and cyclosporin A in CF-1 mice deficient in mdr1a P-glycoprotein. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:581–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chadwick D. Safety and efficacy of vigabatrin and carbamazepine in newly diagnosed epilepsy: a multicentre randomised double-blind study. Vigabatrin European Monotherapy Study Group. Lancet. 1999;354:13–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)10531-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang W, Stearns RA. Heterotropic cooperativity of cytochrome P450 3A4 and potential drug–drug interactions. Curr Drug Metab. 2001;2:185–98. doi: 10.2174/1389200013338658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geick A, Eichelbaum M, Burk O. Nuclear receptor response elements mediate induction of intestinal MDR1 by rifampin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:14581–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010173200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giessmann T, May K, Modess C, Wegner D, Hecker U, Zschiesche M, Dazert P, Grube M, Schroeder E, Warzok R, Cascorbi I, Kroemer HK, Siegmund W. Carbamazepine regulates intestinal P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance protein MRP2 and influences disposition of talinolol in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76:192–200. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sisodiya SM, Heffernan J, Squier MV. Over-expression of P-glycoprotein in malformations of cortical development. Neuroreport. 1999;10:3437–41. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199911080-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sisodiya SM, Lin WR, Harding BN, Squier MV, Thom M. Drug resistance in epilepsy: expression of drug resistance proteins in common causes of refractory epilepsy. Brain. 2002;125:22–31. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tishler DM, Weinberg KI, Hinton DR, Barbaro N, Annett GM, Raffel C. MDR1 gene expression in brain of patients with medically intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1995;36:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parasrampuria DA, Lantz MV, Benet LZ. A human lymphocyte based ex vivo assay to study the effect of drugs on P-glycoprotein (P-gp) function. Pharm Res. 2001;18:39–44. doi: 10.1023/a:1011070509191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandler B, Almond L, Ford J, Owen A, Hoggard P, Khoo SH, Back D. The effects of protease inhibitors and nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors on p-glycoprotein expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:551–6. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Owen A, Hartkoorn RC, Khoo S, Back D. Expression of P-glycoprotein, multidrug-resistance proteins 1 and 2 in CEM, CEM (VBL), CEM (E1000), MDCKII (MRP1) and MDCKII (MRP2) cell lines. Aids. 2003;17:2276–8. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000088212.77946.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Owen A, Chandler B, Bray PG, Ward SA, Hart CA, Back DJ, Khoo SH. Functional correlation of P-glycoprotein expression and genotype with expression of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptor CXCR4. J Virol. 2004;78:12022–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.12022-12029.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owen A, Chandler B, Back DJ, Khoo SH. Expression of pregnane-X-receptor transcript in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and correlation with MDR1 mRNA. Antivir Ther. 2004;9:819–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owen A, Goldring C, Morgan P, Chadwick D, Park BK, Pirmohamed M. Relationship between the C3435T and G2677T(A) polymorphisms in the ABCB1 gene and P-glycoprotein expression in human liver. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:365–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitteringham NR, Powell H, Clement YN, Dodd CC, Tettey JN, Pirmohamed M, Smith DA, McLellan LI, Kevin Park B. Hepatocellular response to chemical stress in CD-1 mice: induction of early genes and gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase. Hepatology. 2000;32:321–33. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.9602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schachtschabel DO, Lazarus H, Farber S, Foley GE. Sensitivity of cultured human lymphoblasts (CCRF-CEM cells) to inhibition by thymidine. Exp Cell Res. 1966;43:512–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(66)90079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamashita H, Kazawa T, Minatogawa Y, Ebisawa T, Yamauchi T. Time-course of hepatic cytochrome P450 subfamily induction by chronic carbamazepine treatment in rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5:47–52. doi: 10.1017/S1461145701002747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baldini N, Scotlandi K, Serra M, Shikita T, Zini N, Ognibene A, Santi S, Ferracini R, Maraldi NM. Nuclear immunolocalization of P-glycoprotein in multidrug-resistant cell lines showing similar mechanisms of doxorubicin distribution. Eur J Cell Biol. 1995;68:226–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molinari A, Calcabrini A, Meschini S, Stringaro A, Del Bufalo D, Cianfriglia M, Arancia G. Detection of P-glycoprotein in the Golgi apparatus of drug-untreated human melanoma cells. Int J Cancer. 1998;75:885–93. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980316)75:6<885::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Synold TW, Dussault I, Forman BM. The orphan nuclear receptor SXR coordinately regulates drug metabolism and efflux. Nat Med. 2001;7:584–90. doi: 10.1038/87912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodwin B, Hodgson E, Liddle C. The orphan human pregnane X receptor mediates the transcriptional activation of CYP3A4 by rifampicin through a distal enhancer module. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:1329–39. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.6.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kliewer SA, Willson TM. Regulation of xenobiotic and bile acid metabolism by the nuclear pregnane X receptor. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:359–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barone GW, Gurley BJ, Ketel BL, Lightfoot ML, Abul-Ezz SR. Drug interaction between St. John's wort and cyclosporine. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:1013–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.10088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibson GG, Plant NJ, Swales KE, Ayrton A, El-Sankary W. Receptor-dependent transcriptional activation of cytochrome P4503A genes: induction mechanisms, species differences and interindividual variation in man. Xenobiotica. 2002;32:165–206. doi: 10.1080/00498250110102674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capone D, Aiello C, Santoro GA, Gentile A, Stanziale P, D’Alessandro R, Imperatore P, Basile V. Drug interaction between cyclosporine and two antimicrobial agents, josamycin and rifampicin, in organ-transplanted patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1996;16:73–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baciewicz AM, Baciewicz FA., Jr Cyclosporine pharmacokinetic drug interactions. Am J Surg. 1989;157:264–71. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90541-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spina E, Pisani F, Perucca E. Clinically significant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with carbamazepine. An update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1996;31:198–214. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199631030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greiner B, Eichelbaum M, Fritz P, Kreichgauer HP, von Richter O, Zundler J, Kroemer HK. The role of intestinal P-glycoprotein in the interaction of digoxin and rifampin. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:147–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johne A, Brockmoller J, Bauer S, Maurer A, Langheinrich M, Roots I. Pharmacokinetic interaction of digoxin with an herbal extract from St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;66:338–45. doi: 10.1053/cp.1999.v66.a101944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh D, Alexander J, Owen A, Rustom R, Bone M, Hammad A, Roberts N, Park K, Pirmohamed M. Whole-blood cultures from renal-transplant patients stimulated ex vivo show that the effects of cyclosporine on lymphocyte proliferation are related to P-glycoprotein expression. Transplantation. 2004;77:557–61. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000114594.21317.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asghar A, Gorski JC, Haehner-Daniels B, Hall SD. Induction of multidrug resistance-1 and cytochrome P450 mRNAs in human mononuclear cells by rifampin. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:20–6. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pirmohamed M, Allott R, Green VJ, Kitteringham NR, Chadwick D, Park BK. Lymphocyte microsomal epoxide hydrolase in patients on carbamazepine therapy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;37:577–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1994.tb04307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rizzi M, Caccia S, Guiso G, Richichi C, Gorter JA, Aronica E, Aliprandi M, Bagnati R, Fanelli R, D'Incalci M, Samanin R, Vezzani A. Limbic seizures induce P-glycoprotein in rodent brain: functional implications for pharmacoresistance. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5833–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-05833.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raucy JL. Regulation of CYP3A4 expression in human hepatocytes by pharmaceuticals and natural products. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:533–9. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.5.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schuetz EG, Beck WT, Schuetz JD. Modulators and substrates of P-glycoprotein and cytochrome P4503A coordinately up-regulate these proteins in human colon carcinoma cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:311–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]