Abstract

Formation of atypical isoaspartyl (isoAsp) sites in peptides and proteins via the deamidation-linked isomerization of asparaginyl-Xaa bonds or direct isomerization of aspartyl-Xaa bonds is a major contributor to spontaneous protein damage under mild conditions. This nonenzymatic reaction reroutes the Asx-Xaa peptide bond through the β-carbonyl of asparaginyl or aspartyl residues, thereby adding an extra carbon to the polypeptide backbone. Formation of isoAsp has been implicated in protein inactivation, aggregation, degradation, and autoimmunity. Knowing the location of isoAsp sites in proteins is important for understanding mechanisms of protein damage and for characterizing protein pharmaceuticals. Here we present a simple nonradioactive method for direct localization of isoAsp residues in peptides or proteins. Using three model peptides, we demonstrate that isoAsp linkages can be cleaved selectively and in high yield by a two-step process in which (i) the isoAsp linkage is converted into a succinimide on incubation with S-adenosyl-L-methionine and the commercially available enzyme, protein L-isoaspartyl-O-methyltransferase, and (ii) the succinimidyl bond is then cleaved by hydroxylamine under conditions that minimize cleavage of the traditional hydroxylamine-sensitive Asn-Gly and related peptide bonds. Location of the isoAsp linkage is then inferred by identifying the cleavage products by mass spectrometry or N-terminal sequencing.

Keywords: Cyclic imide, Hydroxylamine, Isoaspartate, IsoAsp, Protein L-isoaspartyl-O-methyltransferase, S-adenosyl-L-methionine, Succinimide

Formation of isoaspartyl (isoAsp)2 peptide bonds (also known as β-aspartyl bonds) at Asn-Xaa or Asp-Xaa linkages constitutes a major source of spontaneous protein damage under physiological conditions [1-3]. Formation of isoAsp arises from deamidation of asparaginyl-Xaa bonds or direct isomerization of aspartyl-Xaa bonds. This process occurs via a succinimide (cyclic imide) intermediate generated when the C-flanking amide nitrogen makes a nucleophilic attack on the side-chain carbonyl group of the Asx residue (Fig. 1). Hydrolysis of the succinimide generates isoAsp and aspartyl linkages in a ratio that typically ranges from 70:30 to 85:15 [4,5]. The propensity for isoAsp formation is determined by local sequence and structural flexibility. Extensive in vitro studies indicate that sequences containing Asn-Gly, Asn-Ser, Asp-Gly, and Asn-His are most susceptible to isoAsp formation, particularly in highly flexible regions [6,7]. Under normal physiological conditions, the aberrant isoAsp linkage is converted back to a normal peptide bond by protein L-isoaspartyl-O-methyltransferase (PIMT, EC 2.1.1.77), a highly conserved and ubiquitous enzyme (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mechanism of hydroxylamine cleavage of an isoAsp-Xaa linkage following PIMT-catalyzed cyclic imide formation. The upper half of the diagram shows the biologically relevant pathway for PIMT-mediated repair of an abnormal isoAsp linkage to produce a normal aspartyl peptide bond. The key feature of this pathway is the formation of metastable cyclic imide (succinimide) intermediate, which has a half-life of several hours at neutral pH. When present, hydroxylamine can react with either, or both, of the two cyclic imide carbonyl carbons to cleave the peptide. The N-terminal portion of the original peptide will contain an aspartyl N-hydroxyimide or dihydroxamate at its new C terminus. The C-terminal portion of the original peptide will begin with an unmodified amino acid (typically Gly or Ser) as its new N-terminal residue. N-terminal sequencing or mass spectrometry of the new C-terminal peptide provides information on the site of cleavage. The hydroxylamine reaction mechanism shown here is based on the work of Bornstein and Balian [21] and Blodgett and coworkers [22]. AdoHcy, S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine.

Because isoAsp formation can decrease protein activity, promote aggregation, and elicit autoimmunity, it is an important concern in the production and formulation of protein pharmaceuticals as well as in basic research on protein structure and function [8]. Examples of pharmaceutical proteins with a tendency to accumulate isoAsp sites at physiological pH and temperature include recombinant human forms of growth hormone [9], tissue plasminogen activator [10], and interleukin 11 [11]. Examples of proteins found to accumulate isoAsp sites in vivo include tubulin [12], histone H2B [13], and the synaptic vesicle-associated protein synapsin I [14]. Quantitation and identification of isoAsp sites in proteins are important in understanding the factors that contribute to protein heterogeneity in both a pharmaceutical and a biological context.

The overall content of isoAsp in a polypeptide can be conveniently determined by its ability to accept methyl groups from S-adenosyl-L-methionine (AdoMet) in a reaction catalyzed by the PIMT enzyme [15,16]. PIMT is available commercially as part of an isoAsp detection kit that can be used in either a radioisotope-based or a HPLC-based assay format. The PIMT enzyme has also proved to be useful in determining the location of isoAsp sites within a protein sequence. To do this, a tryptic digest of the analyte protein is methylated by PIMT to radiolabel the iso-Asp-containing peptides, which are then separated by HPLC and identified by Edman sequencing and/or mass spectrometry. In cases where a peptide contains more than one Asx residue, determining the distribution of isoAsp sites can be challenging. We have used PIMT-dependent radiolabeling in combination with HPLC to estimate the number of isoAsp sites within a given tryptic peptide[10,17]. The position of the isoAsp site(s) was then determined, where possible, by making use of the fact that Edman degradation is blocked at isoAsp linkages [18]. Recently reported approaches to localizing isoAsp sites in peptides use either collision-induced or electron capture peptide fragmentation in a mass spectrometer to produce ions whose relative abundance depends on the nature (α vs. β) of the Asp-Xaa linkage [19] or to identify isoAsp/Asp diagnostic ions of a defined and multiply charged peptide [20].

In the current communication, we describe a new and relatively simple method to localize isoAsp sites in polypeptides. This method is based on the observation that hydroxylamine, a reagent commonly used to cleave Asn-Gly bonds under alkaline conditions [21], does not react directly with the Asn-Gly bond but rather reacts with the succinimide to which it rapidly degrades at high pH [22,23]. We reasoned that one could shift the specificity of hydroxylamine to preferentially cleave isoAsp sites at neutral pH by using PIMT to specifically esterify the α-carboxyl group for its facile conversion to the succinimide under mild conditions. To test this idea, we used matched pairs of three different Asx-containing peptides. One member of each pair contained a succinimide-prone Asn-Xaa or Asp-Xaa bond, whereas the other member of each pair was a homologous peptide with an isoAsp-Xaa bond. For all three peptide pairs, we found a marked preference for cleavage of the isoAsp form at neutral pH.

Materials and methods

General reagents

AdoMet was purchased from Sigma. Hydroxylamine hydrochloride was purchased from Mallinckrodt. Recombinant rat protein L-isoaspartyl-O-methyltransferase (rrPIMT) was purified from Escherichia coli as described previously [24]. The PIMT enzyme is available from Promega as part of its IsoQuant isoAsp detection kit.

Peptides

Complete sequences of the peptides used in this study are shown in Table 1. The peptide names are based on the amino terminal residue single letter code and the overall length. Peptide A13 was synthesized using solid-phase 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) chemistry by the peptide synthesis laboratory at the University of California, Irvine. Peptide M26 (hepatitis B virus pre-S region, residues 120-125) was purchased from Sigma. Peptides K12 (chicken lactate dehydrogenase M4 isozyme, residues 231-242) and K12′ were synthesized in the laboratory of David Glass at Emory University and have been described previously [25].

Table 1.

Sequences and cleavage yields of test peptides

| Peptide | Sequence | Cleavage yield (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 7.0, 45°C | pH 7.5, 60°C | pH 9.0, 45°C | ||

| A13 | AWIVN-GYAIKLPV | 7 | ||

| A13′ | AWIVD^GYAIKLPVa | 82 | ||

| K12 | KQVVD-SAYEVIK | 0 | 1 | |

| K12′ | KQVVD^SAYEVIKa | 22 | 68 | |

| M26 | MQWN-STTFHQTLQDPRVRGLYFPAGG | 0 | 10 | |

| M26′ | MQWD^STTFHQTLQDPRVRGLYFPAGGa | 19 | 61 | |

Note. All peptides were methylated at pH 7.0 and 37 °C for 1 h, as described Materials and methods, and then were incubated with 2.0 M hydroxylamine in Materials and for 2 h under the conditions indicated above.

The symbol ^ indicates an isoAsp peptide (β-aspartyl) bond.

Peptides A13′ and M26′ were prepared by deamidation of A13 and M26 peptides, respectively. Solutions containing 50 μM peptide and 0.1 M NH4OH (pH 10) were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C (A13) or 60 °C (M26). For A13, HPLC of the deamidation reaction yielded two well-separated peaks corresponding to the isoAsp and Asp forms of this peptide The identity of the isoAsp form was verified by mass spectrometry combined with its ability to be methylated stoichiometrically by PIMT in a methanol difusion assay [16]. For M26, deamidation yielded only one peak (M26′) in HPLC that was found to be a mixture of 74% isoAsp peptide and 26% Asp peptide. This was determined by the following three findings. First, mass spectrometry of the peak indicated one mass corresponding to a deamidated form of the parent M26 peptide. Second, methylation of M26′ by PIMT, as judged by the methanol difusion assay, was high but substoichiometric. Third, as shown in Fig. 2C, methylation of M26′ moved 74% of it to a higher retention time (as expected for the isoAsp methyl ester) regardless of whether methylation was carried out for 15 or 60 min.

Fig. 2.

Methylation efficiency and purity of the A13′ (A), K12′ (B), and M26′ (C) isoAsp peptides as determined in RP-HPLC. The top panel in each series shows the HPLC trace obtained with the unmodified peptide. Lower traces show the HPLC profiles after 15 and 60 min of methylation by PIMT as described in Materials and Methods. As expected, the methylated form of each peptide elutes significantly later than does the unmodified peptide. The fact that the 15- and 60-min profiles are virtually identical for a given peptide indicates that methylation is complete by 15 min in all cases. The material that was resistant to methylation, comprising approximately 5% of A13′ and 26% of M26′, represents nonmethylatable contaminants. For M26′, this contaminant is presumed to be mainly the normal aspartyl form given that it has the same mass as the isoAsp form.

Methylation reactions

To prepare peptides for hydroxylamine cleavage, methylation priming reactions were carried out in a final volume of 100 μl containing 10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 20 μM peptide, 250 μM AdoMet, and 3 μM PIMT. Reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h and then stopped by freezing at -20 °C.

Hydroxylamine cleavage

A hydroxylamine stock solution (4 M) was prepared by dissolving hydroxylamine hydrochloride in purified water; adjusted to pH 7.0, 7.5, or 9.0 with sodium hydroxide; and filtered through a 0.45-μm Millipore filter. To initiate the cleavage reaction, 100 μl of hydroxylamine stock solution was added to the primed peptide solution described above. For cleavage reactions at pH 7.5 or pH 9.0, the pH of the primed peptide solution was adjusted with 1 M Na-phosphate (pH 7.5) or 1 M Na-borate (pH 9.0) just before the addition of hydroxylamine. The reaction was then incubated at either 45 or 60 °C as indicated in Table 1. The cleavage products subsequently were analyzed by reversed-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) and mass spectrometry.

HPLC

Peptides were separated by gradient elution on a 100 × 4.6-mm Aquapore RP-300 column from Applied Biosystems using a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. Solvent A was 10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.0), and solvent B was 5 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.0) containing 50% (v/v) acetonitrile. Linear gradients were applied by increasing solvent B to a maximum of 85% (42.5% acetonitrile). Elution profiles were monitored by UV absorption at 278 and 214 nm.

Mass spectrometry

Peptides collected from HPLC runs were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization paired with Fourier transform mass spectrometry (MALDI-FTMS) in the laboratory of Robert McIver at the University of California, Irvine. The prototype mass spectrometry used in this study has been described in detail elsewhere [26]. In a typical analysis, 0.5μl of analyte (containing 5-10pmol of peptides in acetonitrile/water, 1:1) was mixed with 0.5μl of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (10mg/ml in ethanol), deposited on a stainless-steel direct insertion probe, and allowed to dry. The sample was ionized by a nitrogen laser at 337nm and was transported by the RF-only quadruple ion guide through the fringing field of 6.5T superconducting magnet. All ions were analyzed in the FTMS cell. Periodic mass calibration curves were generated from a mixture of the following external standards: [Arg8]vasopressin, melittin, bovine insulin β-chain, and whole bovine insulin. Under optimal conditions, using external standardization, this machine was capable of demonstrating an average mass error (Δm/m) of 3.3ppm for peptides in the range of 1084 to 5738. For the analyses reported here, the time between external standardization and sample analysis varied considerably, with the result that our samples exhibited mass deviations as high as 45.1ppm compared with the expected values. Because we were interested only in identifying possible cleavage products from peptides of known structure, this level of mass accuracy was considered well within acceptable limits.

Results and discussion

Peptide purity and methylation efficiency

The three pairs of test peptides used in this study are shown in Table 1. Before attempting hydroxylamine cleavage, we investigated the efficiency and time course of methylation of these peptides by PIMT. This is important because methylation is a key step in rendering the isoAsp sites susceptible to hydroxylamine cleavage. To assess methylation efficiency, each peptide was incubated with PIMT and AdoMet at 37 °C (pH 7.0) for 15 or 60 min. Stopped reactions were then analyzed by RP-HPLC, the results of which are shown in Fig. 2. For peptide A13′ or K12′, methylation shifted at least 95% of the starting peptide (top panels) to a higher retention time, as expected in this reversed-phase system. For all three peptides, methylation was essentially complete by 15 min. For M26′, methylation moved 74% of the starting peptide peak area to a higher retention time with little diference between 15 and 60 min of methylation. As described in Materials and methods, we obtained M26′ by deamidation of M26 (the Asn form) but were unable to separate the expected isoAsp and Asp products in RP-HPLC that typically are generated in ratios ranging from 2:1 to 5:1. The results in Fig. 2C indicate that the M26′ peptide contains 74% isoAsp form and that this isoAsp fraction is completely methylated after 15 min of methylation. Cleavage eficiencies for M26′reported in Table 1 and elsewhere in this study all are corrected for the 74% isoAsp content.

Hydroxylamine cleavage

Peptides A13, A13′, K12, K12′, M26, and M26′ were primed for hydroxylamine cleavage by incubation with PIMT and AdoMet for 60 min at pH 7.0 and 37 °C. We used 60 min rather than 15 min to favor maximal yield of the succinimide intermediate based on previous experiments with model isoAsp peptides [27]. At the end of this incubation, hydroxylamine was added to a final concentration of 2.0 M and incubation was continued for 2 h at pH 7.0 and 45 °C. To assess the degree of Asx-Xaa bond cleavage, the reaction mixture was then subjected to RP-HPLC to separate and identify the resulting products.

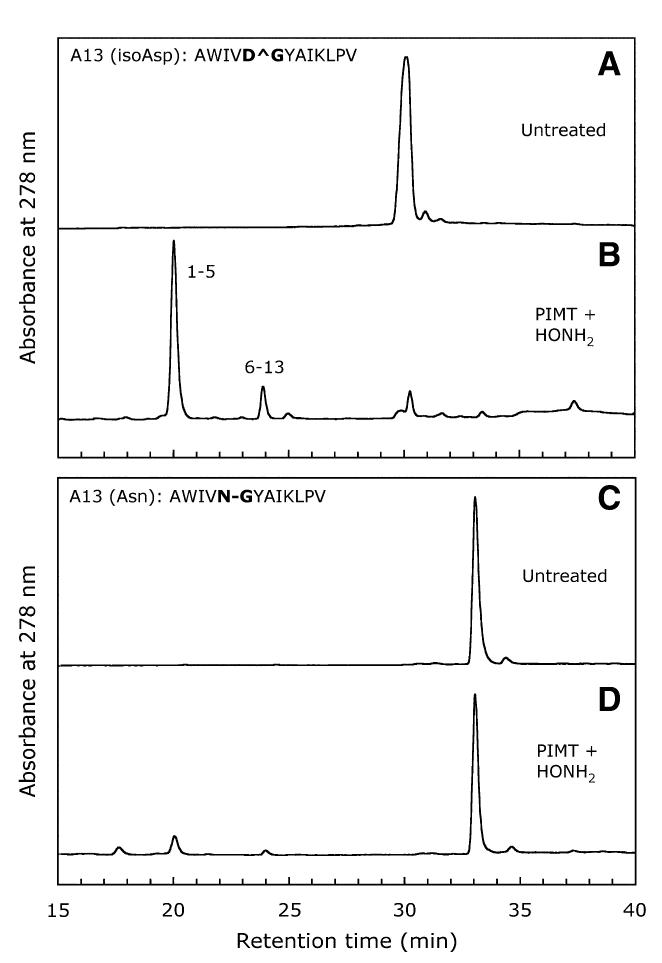

The series of HPLC traces used to assess cleavage of the A13′ and A13 peptides is shown in Fig. 3. The untreated A13′ isoAsp peptide appears as a single major peak eluting at 30 min (Fig. 3A). After methylation and hydroxylamine treatment, the peak at 30 min is largely replaced by two new peaks eluting at 20 and 24 min (Fig. 3B). Mass data (Table 2 and Fig. 4) revealed that these two peaks correspond to the 1-5 and 6-13 fragments of A13′, respectively, indicating that efficient cleavage of the isoAsp peptide bond had occurred. The mass of the 1-5 fragment corresponds to the expected N-hydroxyimide form as illustrated in Fig. 1. We found no evidence for the dihydroxamate form.

Fig. 3.

HPLC profiles obtained after hydroxylamine cleavage of A13′ and A13 peptides following PIMT-mediated priming. In panels B and D, peptides were methylated by PIMT at pH 7.0 and 37 °C for 1 h and then were cleaved with 2 M hydroxylamine at pH 7.0 and 45 °C for 2 h.

Table 2.

Masses of test peptide cleavage products

| Peptide | Fragment | Monoisotopic mass (m/z) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | Change | ||

| A13′ | 1–5a | 600.3138 | 600.3138 | 0.0000 |

| 6–13 | 860.5105 | 860.5240 | –0.0135 | |

| K12′ | 1–5b | — | — | — |

| 6–12 | 809.4768 | 809.4403 | 0.0365 | |

| M26′ | 1–4a | 576.2223 | 576.2233 | –0.0010 |

| 5–26 | 2448.2117 | 2448.2419 | –0.0302 | |

Only the N-hydroxyimide form was found.

No N-terminal fragment was found.

Fig. 4.

Identification of the A13′ 6-13 cleavage product that elutes at 24 min in Fig. 3B by MALDI-FTMS. The conditions for FTMS are described in Materials and methods. Panel A shows a scan over the m/z range of 500 to 1000. Monoisotopic masses are shown. The theoretical mass of the 6-13 fragment is 860.5240 compared with the value of 860.5105 found here (see also Table 2). In panel B, the isotopic spectrum of this peak shows the expected relative masses and peak amplitudes for the 6-13 fragment. The peak in panel A with m/z = 646.4 matches the predicted m/z for a decomposed component of the 6-13 fragment consisting of YAIKL plus a potassium ion.

The technique described here would be of little use if it did not discriminate between an isoAsp-Gly bond and an Asn-Gly bond. Therefore, we subjected peptide A13, the Asn-Gly homolog of A13′, to the same protocol. Untreated A13 elutes as a single major peak at 33 min (Fig. 3C). Methylation and hydroxylamine treatment of A13 resulted in some cleavage of the Asn-Gly bond, as evidenced by minor peaks at 20 and 24 min (Fig. 3D), but the extent of cleavage was quite small compared with that of the A13′ peptide.

The cleavage efficiencies obtained with all six of our test peptides are included in Table 1. When the hydroxylamine step was carried out at pH 7.0 and 45 °C, these eficiencies ranged from 19 to 82% for the isoAsp peptides and from 0 to 7% for the normal peptides. In an attempt to boost the cleavage yield of the two isoAsp-Ser peptides (K12′ and M26′), we tried raising the temperature and/or pH during the hydroxylamine treatment. For the K12′ and K12 peptides, incubation at pH 7.5 and 60 °C increased cleavage to 68 and 1%, respectively. For the M26’ and M26 peptides, changing the pH to 9 increased cleavage to 61 and 10%, respectively, while maintaining a favorable 6:1 preference for the isoAsp form.

Kinetics of hydroxylamine cleavage

All of the cleavage eficiencies reported in Table 1 were based on a 2-h incubation with hydroxylamine. In Fig. 5, we show the kinetics of cleavage for all six peptides using the optimal conditions for each peptide pair. Incubation times longer than 2 h increased the percentage cleavage of the A13′/A13 and M26′/M26 peptides, but the specificity ratio did not change significantly beyond 2 h for any of the three peptide pairs.

Fig. 5.

Kinetics of PIMT-primed hydroxylamine cleavage for control and isoAsp peptide pairs. All peptides were primed by methylation at pH 7.0 and 37 °C for 1 h followed by incubation with 2 M hydroxylamine for the indicated times. Cleavage of the A13 pair (top panel) was carried out at pH 7.0 and 45 °C. Cleavage of the K12 pair (middle panel) was carried out at pH 7.5 and 60 °C. Cleavage of the M26 pair (bottom panel) was carried out at pH 9.0 and 45 °C.

Conclusions

By combining PIMT-catalyzed methylation of isoAsp residues with hydroxylamine cleavage, we have developed a simple method for locating isoAsp sites in peptides. After methyltransferase priming to favorably convert the isoAsp site to the succinimide intermediate under mild conditions, hydroxylamine exhibits an “endoproteinase isoAsp-C” type of specificity. Subsequent identification of the cleavage products by Edman sequencing or mass spectrometry allows unambiguous localization of the isoAsp peptide bond. This technique should prove to be useful in characterizing proteins that are suspected of being damaged or proteins that have been intentionally stressed in the course of stability testing. The recommended approach is to carry out parallel tryptic digestions for control and stressed proteins. After separating the tryptic peptides by HPLC, they can be tested for isoAsp content using the PIMT-mediated methylation reaction. By comparing the isoAsp content of homologous peptides from the control and stressed protein samples, one can distinguish isoAsp levels that are specifically related to the stress treatment. Application of the hydroxylamine protocol described in this article can then be used to directly identify the location(s) of the stress-induced isoAsp site(s).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant NS17269 to D.W.A. We thank Mallik Paranandi for helpful suggestions with the HPLC analyses, and we thank Yunzhi Li and Robert McIver for carrying out the MALDI-FTMS analyses.

Footnotes

- isoAsp

- isoaspartyl

- PIMT

- protein L-isoaspartyl-O-methyltransferase

- AdoMet

- S-adenosyl-L-methionine

- rrPIMT

- recombinant rat protein L-isoaspartyl-O-methyltransferase

- Fmoc

- 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl

- RP-HPLC

- reversed-phase HPLC

- MALDI-FTMS

- matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization paired with Fourier transform mass spectrometry

References

- [1].Clarke S, Stephenson RC, Lowenson JD. Lability of asparagine and aspartic acid residues in proteins and peptides. In: Ahern TJ, Manning MC, editors. Stability of Protein Pharmaceuticals, part A: Chemical and Physical Pathways of Protein Degradation. Plenum; New York: 1992. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Volkin DB, Mach H, Middaugh CR. Degradative covalent reactions important to protein stability. Mol. Biotechnol. 1997;8:105–122. doi: 10.1007/BF02752255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Aswad DW, Paranandi MV, Schurter BT. Isoaspartate in peptides and proteins: Formation isoaspartate in peptides and proteins: Formation, significance, and analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2000;21:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(99)00230-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Johnson BA, Aswad DW. Enzymatic protein carboxyl methylation at physiological pH: Cyclic imide formation explains rapid methyl turnover. Biochemistry. 1985;24:2581–2586. doi: 10.1021/bi00331a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Geiger T, Clarke S. Deamidation, isomerization, and racemization at asparaginyl and aspartyl residues in peptides: Succinimide-linked reactions that contribute to protein degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:785–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Johnson BA, Aswad DW. Deamidation and isoaspartate formation during in vitro aging of purified proteins. In: Aswad DW, editor. Deamidation and Isoaspartate Formation in Peptides and Proteins. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1995. pp. 91–113. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Powell MF. A compendium and hydropathy/flexibility analysis of common reactive sites in proteins: Reactivity at Asn, Asp, Gln, and Met motifs in neutral pH solution. In: Pearlman R, Wang YJ, editors. Formulation, Characterization, and Stability of Protein Drugs: Case Histories. Plenum; New York: 1996. pp. 1–140. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Liu DT-Y. Deamidation: A source of microheterogeneity in pharmaceutical proteins. Trends Biotechnol. 1992;10:364–369. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(92)90269-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Johnson BA, Shirokawa JM, Hancock WS, Spellman MW, Basa LJ, Aswad DW. Formation of isoaspartate at two distinct sites during in vitro aging of human growth hormone. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:14262–14271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Paranandi MV, Guzzetta AW, Hancock WS, Aswad DW. Deamidation and isoaspartate formation during in vitro aging of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:243–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhang W, Czupryn JM, Boyle Jr PT, Amari J. Characterization of asparagine deamidation and aspartate isomerization in recombinant human interleukin-11. Pharm. Res. 2002;19:1223–1231. doi: 10.1023/a:1019814713428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ohta K, Seo N, Yoshida T, Hiraga K, Tuboi S. Tubulin and high molecular weight microtubule-associated proteins as endogenous substrates for protein carboxymethyltransferase in brain. Biochimie. 1987;69:1227–1234. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(87)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Young AL, Carter WG, Doyle HA, Mamula MJ, Aswad DW. Structural integrity of histone H2B in vivo requires the activity of protein L-isoaspartyl O-methyltransferase, a putative repair enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:37161–37165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Reissner KJ, Paranandi MV, Luc TM, Doyle HA, Mamula MJ, Lowenson JD, Aswad DW. Synapsin I is a major endogenous substrate for protein L-isoaspartyl methyltransferase in mammalian brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:8389–8398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Macfarlane DE. Inhibitors of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases inhibit protein carboxyl methylation in intact blood platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:1357–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Johnson BA, Aswad DW. Optimal conditions for the use of protein L-isoaspartyl methyltransferase in assessing the isoaspartate content of peptides and proteins. Anal. Biochem. 1991;192:384–391. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Potter SM, Henzel WJ, Aswad DW. In vitro aging of calmodulin generates isoaspartate at multiple Asn-Gly and Asp-Gly sites in calcium-binding domains II, III, and IV. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1648–1663. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560021011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Smyth DG, Stein WH, Moore S. The sequence of amino acid residues in bovine pancreatic ribonuclease: Revisions and confirmations. J. Biol. Chem. 1963;238:227–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lehmann WD, Schlosser A, Erben G, Pipkorn R, Bossemeyer D, Kinzel V. Analysis of isoaspartate in peptides by electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Protein Sci. 2000;9:2260–2268. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.11.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Cournoyer JJ, Lin C, O’Connor PB. Detecting deamidation products in proteins by electron capture dissociation. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:1264–1271. doi: 10.1021/ac051691q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bornstein P, Balian G. Cleavage at Asn-Gly bonds with hydroxylamine. Methods Enzymol. 1977;47:132–145. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(77)47016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Blodgett JK, Loudon GM, Collins KD. Specific cleavage of peptides containing an aspartic acid (β-hydroxamic acid) residue. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:4305–4313. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kwong MY, Harris RJ. Identification of succinimide sites in proteins by N-terminal sequence analysis after alkaline hydroxylamine cleavage. Protein Sci. 1994;3:147–149. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].David CL, Aswad DW. Cloning, expression, and purification of rat brain protein L-isoaspartyl methyltransferase. Protein Express. Purif. 1995;6:312–318. doi: 10.1006/prep.1995.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Aswad DW, Johnson BA, Glass DB. Modification of synthetic peptides related to lactate dehydrogenase (231-242) by protein carboxyl methyltransferase and tyrosine protein kinase: Effects of introducing an isopeptide bond between aspartic acid-235 and serine-236. Biochemistry. 1987;26:675–681. doi: 10.1021/bi00377a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Li Y, McIver RT, Jr., Hunter RL. High-accuracy molecular mass determination for peptides and proteins by Fourier transform mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 1994;66:2077–2083. doi: 10.1021/ac00085a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Johnson BA, Murray Jr ED, Clarke S, Glass DB, Aswad DW. Protein carboxyl methyltransferase facilitates conversion of atypical L-isoaspartyl peptides to normal L-aspartyl peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:5622–5629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]