Abstract

The platelet paradigm in hemostasis and thrombosis involves an initiation step that depends on platelet membrane receptors binding to ligands on a damaged or inflamed vascular surface. Once bound to the surface, platelets provide a unique microenvironment supporting the accumulation of more platelets and the elaboration of a fibrin-rich network produced by coagulation factors. The platelet-specific receptor glycoprotein (GP) Ib-IX, is critical in this process and initiates the formation of a platelet-rich thrombus by tethering the platelet to a thrombogenic surface. A role for platelets beyond the hemostasis/thrombosis paradigm is emerging with significant platelet contributions in both tumorigenesis and inflammation. We have established congenic (N10) mouse colonies (C57BL/6J) with dysfunctional GP Ib-IX receptors in our laboratory that allow us an opportunity to examine the relevance of platelet GP Ib-IX in syngeneic mouse models of experimental metastasis. Our results demonstrate platelet GP Ib-IX contributes to experimental metastasis because a functional absence of GP Ib-IX correlates with a 15-fold reduction in the number of lung metastatic foci using B16F10.1 melanoma cells. The results demonstrate that the extracellular domain of the α-subunit of GP Ib is the structurally relevant component of the GP Ib-IX complex contributing to metastasis. Our results support the hypothesis that platelet GP Ib-IX functions that support normal hemostasis or pathologic thrombosis also contribute to tumor malignancy.

Keywords: adhesion, tumor, hemostasis, knockout, melanoma

Circulating blood platelets have an inherent adhesive potential long recognized as essential for hemostasis and thrombosis. Beyond the platelet paradigm for blood clotting and thrombosis, it is becoming apparent that the platelet's adhesive potential influences pathological events outside its role in hemostasis. Indeed, emerging hypotheses suggest the platelet paradigm in hemostasis and thrombosis, an accumulation of platelets and the elaboration of a fibrin matrix, may provide a mechanism for circulating tumor cells to metastasize. Experimental proof that platelets effect tumor metastasis was provided in models where an experimental lowering of circulating platelet counts reduced metastasis (1–3).

Evidence suggests that carcinoma cells entering the circulation interact with both platelets and leukocytes to form tumor cell aggregates (1, 4). Data have suggested one mechanism linking the platelet to metastasis is a platelet “cloak” surrounding the tumor cell and protecting the tumor cell from immune surveillance (5, 6). Tumorigenesis has been linked to several molecules essential for blood coagulation and normal platelet function. These include thrombin, tissue factor, platelet P-selectin, fibrinogen, and lysophosphatidic acid (3, 4, 7–16). Together, these results suggest that platelets and their procoagulant activity support tumor metastasis, possibly by aiding tumor cells to lodge in the microvasculature and either extravasate to the surrounding tissue or grow as an intravascular tumor (17).

Experimental metastasis refers to the injection of tumor cells directly into the circulation. In mouse models of experimental metastasis, the most common injection site is the lateral tail vein, producing major metastases in the lung. The primary involvement of the lung is probably due to the fact that the first capillary bed through which tumor cells pass are in the lung (18). A variety of murine cancer lines have been developed that are useful in transplantable metastasis assays (18). One of the best characterized is the melanoma B16 model, where successive collection of metastases from the lung and reinjection has yielded a series of lines with increasing metastatic potential (19). The syngeneic host-mouse strain for B16 cells, C57BL/6J, is one of the more commonly used laboratory mouse strains. A strength of using a syngeneic model, versus a xenograft model, is the competency of the immune system in the host animal (20).

We present data that experimental metastasis is highly regulated and depends on a specific platelet receptor complex normally reserved for hemostasis and thrombosis. Our data demonstrate that normal platelet functions mediated by the adhesion receptor, GP Ib-IX, are key to processes controlling colonization of the mouse lung by B16 cells. Using a murine model of GP Ib-IX deficiency and models where variants of the α-subunit of the GP Ib-IX complex are expressed on the surface of circulating platelets, we establish that the extracellular domain of GP Ibα is the structural and functional component of the GP Ib-IX complex supporting lung colonization. These studies provide a further understanding of the impact of platelet function on tumor biology and may lead in the development of strategies or adjunct therapies for controlling malignant disease.

Results

Platelet GP Ibα and Experimental Metastasis.

Two mouse models of platelet glycoprotein Ib-IX deficiency have been described (21, 22). Briefly, a knockout of the platelet GP Ibα subunit (GP1b−/−) generates a murine model of the human Bernard–Soulier syndrome (BSS). These mice have a severe bleeding phenotype, macrothrombocytopenia, and no detectable GP Ib-IX receptor on their platelet surface. The second model was developed by partially rescuing the GP1b−/− macrothrombocytopenic phenotype by transgenic expression of a variant GP Ibα subunit (IL-4R). The variant subunit consists of an extracellular domain of the human IL-4 receptor fused to human GP Ibα transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains (22). These mice retain a severe bleeding phenotype, owing to the absence of GP Ibα extracytoplasmic domains but, as compared with GP1b−/− mice, have an increased platelet count and a more normal distribution of platelet size in whole blood (22). For the purpose of the current study, both mouse models have been backcrossed for 10 generations to C57BL/6J mice, generating congenic strains of each model (Fig 1).

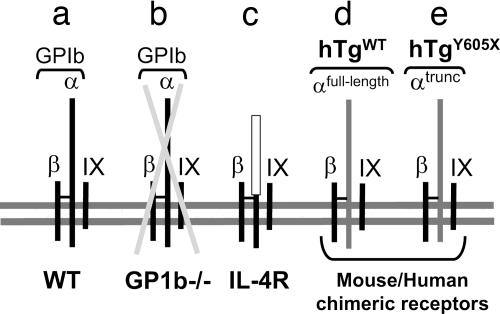

Fig. 1.

Variant platelet GP Ib-IX receptor complexes expressed on the surface of circulating platelets are schematically represented. (a) The WT GP Ib-IX complex consists of three distinct gene products. The disulfide-linked α- and β-subunits of GP Ib and the noncovalently associated GP IX. (b) A mouse model of GP Ib-IX deficiency (GP1b−/−) has been previously described mimicking the human BSS (21). This mouse model of BSS lacks the gene encoding GP Ibα, resulting in a missing complex owing to the three-subunit requirement for efficient surface expression of the complex (48). A hallmark feature of both human mouse BSS is macrothrombocytopenia. The complex depicted in c expresses a variant GP Ibα subunit with an ameliorated macrothrombocytopenia (22). The expressed GP Ibα variant is composed of an extracellular domain from the interleukin-4 receptor fused to coding sequence of a few residues from the GP Ibα extracellular domain and the complete GP Ibα transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains (IL-4R). The disulfide linkage occurring between the IL-4R/GP Ibα fusion and GP Ibβ was confirmed by biochemical analysis (22). (d) A rescue of mouse GP Ibα deficiency was performed by transgenic expression of the human GP Ibα subunit (hTgWT) as was a similar variant lacking the six terminal residues of the GP Ibα subunit (hTgY605X, e) (21, 23).

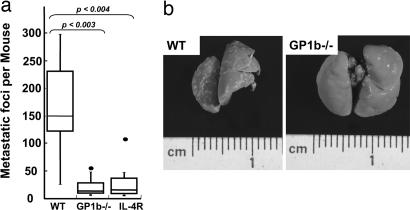

A syngeneic model of experimental metastasis was used to determine the physiologic relevance of platelet GP Ibα in tumorigenesis. Metastatic murine melanoma cells B16F10.1 (B16) were injected into the lateral tail vein of mice, and 14 days later, the extent of lung metastasis was determined. After the mice were killed, lungs were dissected, and the number of surface-visible lung tumors was determined. Results are shown after the injection of 1 × 105 B16 cells in a series of age- and sex-matched control (C57BL/6J), congenic GP1b−/−, and congenic IL-4R animals (Fig. 2). The average number of visible tumors in GP1b−/− was 19-fold less than that observed in control C57BL/6J animals. The median value for GP1b−/− mice was 8, whereas the median value for control lungs was 150 (Fig. 2). The reduction in surface metastases was statistically significant with a P value of 0.003. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments. The number of tumor foci depended strongly on the presence of GP Ib-IX, but the size and overall appearance of individual foci were indistinguishable between control C57BL/6J and GP1b−/− lungs.

Fig. 2.

B16-F10.1 melanoma cells (1 × 105) were injected via a mouse tail vein. Fourteen days later, the lungs were removed, and surface-visible tumors were counted in normal (WT), BSS mice (GP1b−/−), and mice with an absent extracellular domain of platelet GP Ibα (IL-4R). (a) Box plot data represent range, median, and quartile values. Median values are represented by the horizontal line. P values comparing each group are shown. (b) Two representative metastatic lungs are shown for comparison.

As mentioned above, GP1b−/− mice display macrothrombocytopenia with circulating platelet counts ≈1/3 of a normal value. Thus, to determine the significance of the GP1b−/− associated macrothrombocytopenia, we performed experiments using the congenic IL-4R mouse model, still devoid of extracellular GP Ibα functions but with an ameliorated macrothrombocytopenia. Visible lung tumors in IL-4R mice had a median value of 12, as compared with the median value of 150 tumors with C57BL/6J controls (Fig. 2). The reduced number of metastatic foci on IL-4R lungs was again statistically significant, with a P value of 0.004. No statistical difference was observed between GP1b−/− and IL-4R lungs.

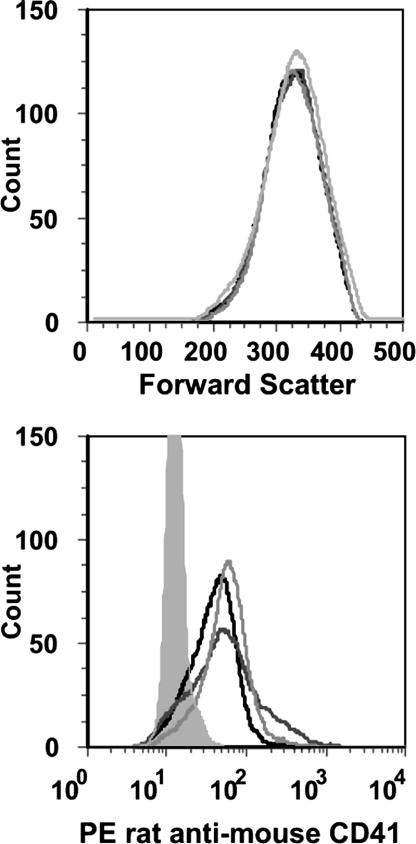

To further evaluate platelet/tumor cell interactions, B16 cells were mixed with washed platelets at a 1:200 (B16:platelets) ratio. Flow cytometry analysis gating on tumor cells compared fluorescence in the presence of labeled platelets from C57BL/6J, GP1b−/−, and IL-4R animals. No obvious fluorescent profile differences were seen among the three mouse strains (Fig. 3). Thus, we conclude that under these experimental conditions, there is not a major role for platelet GP Ib-IX in a platelet–tumor cell interaction.

Fig. 3.

Flow cytometry profiles of B16F10.1 cells mixed with washed platelets at a ratio of 1:200 (B16:platelets) are shown. Tumor cell forward scatter profile (Upper) was analyzed for fluorescence (Lower) produced by a platelet-specific phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled rat anti-mouse CD41 (αIIb, glycoprotein IIb) monoclonal antibody. Fluorescent profiles of tumor cells in the presence of platelets from normal mice (C57BL/6J, black line), GP1b−/− animals (dark gray), and IL-4R animals (light gray) are shown. Labeled B16 cells in the absence of washed platelets are shown for comparison (shaded gray area).

Experimental Metastasis and Human GP Ibα.

We have previously described mice devoid of mouse GP Ibα, GP1b−/−, but expressing a platelet-specific transgene encoding human GP Ibα, hTgWT (21). hTgWT mice have a rescued Bernard–Soulier phenotype, as evidenced by increased platelet count, a normal distribution of platelet size, and normal hemostasis. We have also described the generation of a similar mouse colony expressing a truncated form of the human GP Ibα transgene, lacking six terminal residues that interact with the signal transduction protein, 14-3-3ζ (23). These mice, hTgY605X, have been characterized for the relevance of these cytoplasmic residues in megakaryocyte maturation and proliferation (23). We also previously reported the cytoplasmic truncation had no effect on circulating platelet counts or hemostasis, as determined in a tail bleeding-time assay.

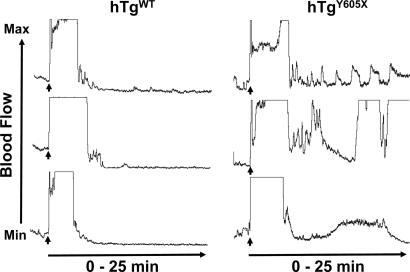

The relevance of these cytoplasmic residues for thrombosis is presented in Fig. 4. In a model of ferric chloride-induced carotid artery injury, mice expressing hTgWT were observed to have a rapid and stable reduction of blood flow, leading to an occlusion that persists for at least 25 min. In total, 10 hTgWT animals were tested, with indistinguishable results from the three representative tracings presented in Fig. 4. This result supports our previous conclusion that human GP Ibα expressed on the surface of mouse GPIb-deficient platelets does rescue the mouse BSS phenotype (21). In contrast, mice expressing the cytoplasmic truncation, hTgY605X, had impaired thrombosis in this model. Blood flow reduction indicative of thrombus formation occurred, but in contrast to hTgWT, there was evidence of fluctuating blood flow, indicative of embolization and an inability to completely occlude the vessel (Fig. 4). Similar results were obtained from 10 different animals, and three representative tracings are shown (Fig. 4). Thus, truncation of GP Ibα does impact thrombosis in this ferric-chloride model and presumably relates to alterations in a GPIbα/14-3-3ζ signaling pathway, an idea proposed by others (24, 25).

Fig. 4.

A mouse model with a truncated GP Ibα subunit expresses a receptor lacking 6 aa from the cytoplasmic COOH terminus of the human GP Ibα subunit and is designated hTgY605X (right tracings). A similar mouse colony expressing the normal human GP Ibα subunit has also been generated, hTgWT (left tracings). Congenic strains of both mouse models are now available and have been tested in an in vivo model of thrombus formation. A 10% FeCl3-soaked filter is placed on the surface of an exposed carotid artery for 3 min. After removal of the filter, blood flow through the carotid is measured by using a laser Doppler probe. The representative tracings from three different mice of each colony follow blood flow from a maximum value (top of the graph) to a minimum value that represents occlusion of the carotid (bottom of the graph). The FeCl3 filter was removed at the time point designated by the arrow. The graphs are representative of 10 individual measurements from each mouse strain.

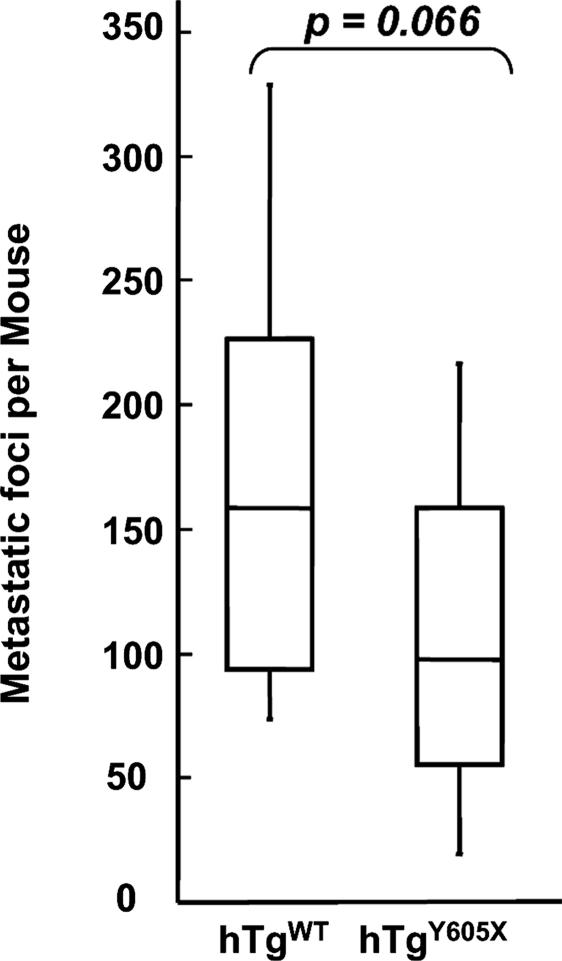

Having established both hTgWT and hTgY605X animals as congenic strains, experiments were performed to determine whether human GP Ibα supports experimental metastasis and to determine whether the cytoplasmic interactions, such as GP Ibα/14-3-3ζ signaling pathways, might contribute to the process. B16 cells were injected in the tail veins of hTgWT and hTgY605X animals. The expression of human GP Ibα in this model of mouse GP Ibα deficiency produced a significant number of visible tumors, median = 157, thus confirming the ability of human GP Ibα to support tumor development (Fig. 5). Likewise, the six-residue truncation of GP Ibα did not significantly impact the relevance of GP Ibα to support metastasis (median value, = 96). No statistical significance was observed between the two groups (P value of 0.066). This result demonstrates that human GP Ibα supports metastasis and the GP Ibα/14-3-3ζ-dependent signaling pathways are not relevant to the formation of lung tumors in this model of experimental metastasis. These results indicate that GP Ib-IX can support experimental metastasis in platelets unable to form stable thrombi. In combination with results obtained with IL-4R mice, these results support the hypothesis that the extracellular domain of platelet GP Ibα supports experimental metastasis.

Fig. 5.

B16-F10.1 melanoma cells (1 × 105) were injected via a mouse tail vein. Fourteen days later, the lungs were removed, and surface-visible tumors were counted from mice expressing a human GP Ibα subunit (hTgWT) and mice with a truncated cytoplasmic tail of GP Ibα (hTgY605X). Box plot data represent range, median, and quartile values. Median values are represented by the horizontal line.

Discussion

Although the in vivo role of platelet GP Ib-IX in hemostasis and thrombosis is well established (26–28), its role in other biological events is only minimally appreciated. In the past decade, there has been a growing appreciation for the platelet in a variety of processes from tumorigenesis to inflammation (4, 29, 30). One recent example is mice deficient in functional GP Ib-IX exhibiting impaired angiogenesis (27). A few reports have documented that GP Ibα can function as a counterreceptor for P-selectin (31) while supporting a platelet–leukocyte interaction via the integrin receptor, Mac-1 (32, 33). Defining the binding proteins to the GP Ib-IX complex is important, but defining the physiologic relevance of the binding becomes the greater goal. As one of the major receptor complexes on the platelet surface, the role of platelet GP Ib-IX in these processes warrants further consideration, given the wealth of reagents and information that have been developed in the study of hemostasis and thrombosis. To this end, we examined the in vivo relevance of GP Ib-IX using a model of experimental metastasis.

Our studies provide evidence that a primary adhesion receptor for platelets, GP Ib-IX, also participates in metastasis because its functional absence coincides with reduced experimental metastasis. Our results appear, at first glance, to be independent of the major GP Ib-IX ligand, von Willebrand factor (vWF), because it has been reported that vWF-deficient mice have an unexpected increase in metastatic potential (34). However, the results presented here and those from the vWF-deficient mouse might be linked if the increased metastatic potential in vWF-deficient animals is due to an increased availability of platelet GP Ib-IX in the absence of vWF. However, because vWF is a constituent of the plasma and subendothelial matrix, the mechanism by which vWF participates in the metastatic process remains unclear.

An obvious question is at what point in tumor metastasis does platelet GP Ib-IX influence experimental metastasis. Perhaps the role of GP Ib-IX is related to the local environment at the site of tumor formation. It seems clear that the establishment of a fibrin-rich network surrounding the tumor cell is important because several inhibitors of blood coagulation, albeit at high concentrations, have been associated with reduced metastasis (4, 9, 35). We have recently reported that the function of GP Ib-IX in normal hemostasis exceeds that predicted by its interaction with vWF further supporting a role for GP Ib-IX beyond primary platelet adhesion (28). Indeed, the α-subunit of GP Ib contains a thrombin-binding site that is well characterized at the biochemical level, but the in vivo relevance of thrombin binding to GP Ib-IX has remained elusive (36–38).

From a molecular standpoint, P-selectin has been identified as critical for the cell–cell interactions that facilitate platelet-mediated metastasis because P-selectin-deficient platelets have fewer tumor cell–platelet interactions (4, 13). P-selectin was originally identified as a marker of activated platelets (39, 40). Whether sufficient P-selectin on unactivated platelets supports binding to tumor cells is unclear. Nevertheless, increased expression by tumor cells of P-selectin ligands, such as sialyl Lewisx or glycosaminoglycans, correlate with a poor prognosis owing to increased metastatic spread (41, 42). This suggests a mechanism whereby P-selectin expressed on platelets mediates an interaction with tumor cells (4). Indeed, platelet activation may be critical to this interaction because mice deficient in the signaling protein, Gαq, also have decreased metastatic potential (6).

Some have suggested the molecular steps required for metastasis are similar for all solid tumors (43, 44). In future studies, we can expand our results to include additional cell lines and possibly follow the kinetic fate of tumor cells after tail vein injection by using in vivo imaging technologies (45). An additional future direction should be to examine the relevance of GP Ib-IX in models of spontaneous tumor development, a model that may more closely mimic the catastrophic events leading to a poor prognosis in human cancer. However, the current results do suggest that targeting the platelet-specific GP Ib-IX complex may have merit in the control and management of malignant disease. Whether such a strategy is possible without excessive blood loss owing to impaired hemostasis will have to be carefully evaluated. It may be that reducing metastasis by GP Ib-IX blockade comes with the added complication that excessive bleeding near a growing tumor is more harmful than the metastatic disease. Nevertheless, given the poor prognosis associated with metastatic disease, this is another potential direction for therapeutic intervention.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

Control C57BL/6J animals were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). GP Ib-IX-deficient animals have been described and were generated by a gene-targeting strategy of the mouse GP Ibα gene (GP1b) (21). The platelet GP Ib-IX receptor complex is assembled from three distinct platelet-specific gene products, with mutations in any of the subunits producing the BSS. Mutations in the gene encoding the α-subunit of GP Ib are the most common molecular basis for the BSS phenotype (46). In the mouse model of GPIbα-deficiency, the coding sequence for GP Ibα was deleted, leading to a complete lack of detectable platelet GP Ib-IX (21). The mouse BSS colony was backcrossed (10 generations, N10) with C57BL/6J mice purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. The breeding scheme involved stabilizing the mouse Y chromosome in generation one (N1) by using male C57BL/6J animals and choosing heterozygous male offspring for subsequent generations. The breeding of heterozygous GP1b+/− animals to normal C57BL/6J animals in generation 10, led to GP1b+/− progeny that were bred to each other, generating homozygous mice of the BSS phenotype (B6.129S7-GP1btm1). For simplicity in the manuscript, these animals are referred to GP1b−/−. All GP1b−/− mice used in this study had been previously screened by flow cytometry to confirm the absence of a mouse GP Ib-IX complex.

Three additional mouse colonies expressing variants of the GP Ibα subunit have been described (21–23). In brief, each colony has been bred onto a mouse background devoid of murine GP Ibα alleles (GP1b−/−) and back-crossed with control C57BL/6J animals for 10 generations to generate congenic animals in a similar strategy described above. However, in each case, animals were screened by flow cytometry at each generation to ensure the presence of a transgenic product. One colony expresses a variant GP Ibα subunit where most of the extracytoplasmic sequence of GP Ibα has been replaced by an isolated domain of the IL-4 receptor fused to the transmembrane and cytoplasmic residues of GP Ibα (22). In this article, these congenic animals are designated, IL-4R. Two additional colonies expressing transgenic products express either the full-length human GP Ibα sequence (designated, hTgWT) or a six-residue truncation of the cytoplasmic tail (designated, hTgY605X) (21, 23). All animal procedures have been performed in accordance with institutional guidelines and approval.

Antibodies and Flow Cytometry.

Whole blood was analyzed by flow cytometry (FACscan, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) using a variety of phycoerythrin-labeled or FITC-conjugated antibodies. An anti-mouse CD41 (anti-GPIIb or αIIb) monoclonal antibody (Cat. no. 558040; BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) was used to identify the platelet population in whole blood. After identifying the platelet population, a gate was set in the flow cytometer to analyze fluorescence produced by a second labeling with a FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD42b (anti-GP Ibα) monoclonal antibody to confirm the absence of mouse GP Ibα [Xia.G; available from Emfret Analytics (Eibelstadt, Germany)]. For the confirmation of human transgene expression, a FITC-conjugated mouse anti-human CD42b monoclonal antibody (Cat. No. 555472; BD Pharmingen) was used.

To evaluate the B16F10.1-platelet interaction, whole blood was drawn from anesthetized mice via the retroorbital plexus by using heparinized capillary tubes. Platelet-rich plasma was removed after centrifugation (200 × g for 5 min), and a platelet pellet was generated after another centrifugation [2,000 × g for 5 min). Platelets were resuspended in modified Tyrode's buffer (140 mM NaCl/2.7 mM KCl/10 mM NaHCO3/0.42 mM Na2HPO4/5 mM dextrose/1 mM CaCl2/10 mM Hepes (pH 7.4)] and washed a second time after a similar centrifugation and resuspension in modified Tyrode's buffer. Platelet counts were determined, and tumor cells were added to generate a final ratio of 1:200 (tumor cell-to-platelets). The samples were kept at room temperature (RT) for ≈20 min, antibody was added (30-min RT incubation), and the mixture was diluted 3-fold with modified Tyrode's buffer before analysis by flow cytometry.

Cells.

B16-F10.1 were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 units/ml streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine, 10 mM Hepes, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate in the presence of 5% CO2.

Experimental Metastasis.

B16F10.1 cells were supplied with fresh medium 1 day before their harvest for tail vein injection. Subconfluent cells (70–80%) were washed with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline and detached by brief exposure to trypsin (0.25% trypsin and 0.2%EDTA) and washed twice with serum-free medium. Cells were resuspended in serum- free medium and kept on ice until injection. Viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion and was always more than 95%. Two hundred μl of a tumor cell (1 × 105 cells) suspension was injected to the lateral tail vein of mice by using a 27-gauge needle.

Quantitation of Surface Pulmonary Metastatic Foci.

Mice containing lung tumors were killed on day 14 after tumor cell injection. The lungs were removed and rinsed in saline and weighed. Lungs were kept in Bouin's fixative for 24 h before counting. Individual lobes were separated, and the number of surface-visible metastases was determined by using a stereomicroscope (×2 magnification; Tritech Research, Los Angeles, CA). Statistical analysis was performed by using the Student's t test.

Ferric Chloride-Induced Thrombosis.

For ferric chloride (FeCl3)-induced carotid artery injury, the carotid artery was exposed on anesthetized mice (2.5% isoflurane). A 4 × 10-mm strip of Whatman No. 1 filter paper was soaked with 10% FeCl3 and placed on the exposed artery for 3 min. After removal of the filter paper, the exposed area was thoroughly rinsed with isotonic saline. Blood flow was monitored by using a laser Doppler system (Trimflo; Vasamedics, Eden Prairie, MN) connected to a BPM2 blood perfusion monitor (Vasamedics) interfaced via an analogue to digital output with software from PowerLab System (AD Instruments, Castle Hill, Australia) (47).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL50545 (to J.W.) and NIH Cancer Institute Grant CA095458 (to B.F-H.). J.A.G. is funded by a fellowship from the Ministerio de Educaión y Ciencia (Spain).

Abbreviations

- GP

glycoprotein

- BSS

Bernard–Soulier syndrome

- IL-4R

interleukin-4 receptor

- B16

B16F10.1 melanoma.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Karpatkin S, Pearlstein E. Ann Intern Med. 1981;95:636–641. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-95-5-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gasic GJ. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1984;3:99–114. doi: 10.1007/BF00047657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camerer E, Qazi AA, Duong DN, Cornelissen I, Advincula R, Coughlin SR. Blood. 2004;104:397–401. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borsig L, Wong R, Feramisco J, Nadeau DR, Varki NM, Varki A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3352–3357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061615598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieswandt B, Hafner M, Echtenacher B, Mannel DN. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1295–1300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palumbo JS, Talmage KE, Massari JV, La Jeunesse CM, Flick MJ, Kombrinck KW, Jirouskova M, Degen JL. Blood. 2005;105:178–185. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esumi N, Fan D, Fidler IJ. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4549–4556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu L, Lee M, Campbell W, Perez-Soler R, Karpatkin S. Blood. 2004;104:2746–2751. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Im JH, Fu W, Wang H, Bhatia SK, Hammer DA, Kowalska MA, Muschel RJ. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8613–8619. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruf W, Mueller BM. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2006;32(Suppl 1):61–68. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-939555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langer F, Amirkhosravi A, Ingersoll SB, Walker JM, Spath B, Eifrig B, Bokemeyer C, Francis JL. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1056–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mueller BM, Reisfeld RA, Edgington TS, Ruf W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11832–11836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim YJ, Borsig L, Varki NM, Varki A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9325–9330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palumbo JS, Kombrinck KW, Drew AF, Grimes TS, Kiser JH, Degen JL, Bugge TH. Blood. 2000;96:3302–3309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta GP, Massague J. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1691–1693. doi: 10.1172/JCI23823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boucharaba A, Serre CM, Gres S, Saulnier-Blache JS, Bordet JC, Guglielmi J, Clezardin P, Peyruchaud O. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1714–1725. doi: 10.1172/JCI22123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al Mehdi AB, Tozawa K, Fisher AB, Shientag L, Lee A, Muschel RJ. Nat Med. 2000;6:100–102. doi: 10.1038/71429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanna C, Hunter K. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:513–523. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poste G, Doll J, Hart IR, Fidler IJ. Cancer Res. 1980;40:1636–1644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mueller BM, Reisfeld RA. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1991;10:193–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00050791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware J, Russell S, Ruggeri ZM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2803–2808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050582097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanaji T, Russell S, Ware J. Blood. 2002;100:2102–2107. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanaji T, Russell S, Cunningham J, Izuhara K, Fox JE, Ware J. Blood. 2004;104:3161–3168. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng S, Christodoulides N, Reséndiz JC, Berndt MC, Kroll MH. Blood. 2000;95:551–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai K, Bodnar R, Berndt MC, Du X. Blood. 2005;106:1975–1981. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andrews RK, Gardiner EE, Shen Y, Whisstock JC, Berndt MC. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:1170–1174. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(02)00280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kisucka J, Butterfield CE, Duda DG, Eichenberger SC, Saffaripour S, Ware J, Ruggeri ZM, Jain RK, Folkman J, Wagner DD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:855–860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510412103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergmeier W, Piffath CL, Goerge T, Cifuni SM, Ruggeri ZM, Ware J, Wagner DD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16900–16905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608207103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pinedo HM, Verheul HM, D'Amato RJ, Folkman J. Lancet. 1998;352:1775–1777. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)05095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner DD, Burger PC. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:2131–2137. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000095974.95122.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romo GM, Dong JF, Schade AJ, Gardiner EE, Kansas GS, Li CQ, McIntire LV, Berndt MC, Lopez JA. J Exp Med. 1999;190:803–809. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.6.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ehlers R, Ustinov V, Chen Z, Zhang X, Rao R, Luscinskas FW, Lopez J, Plow E, Simon DI. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1077–1088. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Sakuma M, Chen Z, Ustinov V, Shi C, Croce K, Zago AC, Lopez J, Andre P, Plow E, et al. Circulation. 2005;112:2993–3000. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.571315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terraube V, Pendu R, Baruch D, Gebbink MF, Meyer D, Lenting PJ, Denis CV. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:519–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rickles FR, Patierno S, Fernandez PM. Chest. 2003;124:58S–68S. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3_suppl.58s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harmon JT, Jamieson GA. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:13224–13229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mazzucato M, Demarco L, Masotti A, Pradella P, Bahou WF, Ruggeri ZM. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1880–1887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weeterings C, Adelmeijer J, Myles T, de Groot PG, Lisman T. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:670–675. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000200391.70818.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu-Lin S-C, Berman CL, Furie BC, August D, Furie B. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:9121–9126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stenberg PE, McEver RP, Schuman MA, Jacques YV, Bainton DF. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:880–886. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.3.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakamori S, Kameyama M, Imaoka S, Furukawa H, Ishikawa O, Sasaki Y, Kabuto T, Iwanaga T, Matsushita Y, Irimura T. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3632–3637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim YJ, Varki A. Glycoconj J. 1997;14:569–576. doi: 10.1023/a:1018580324971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woodhouse EC, Chuaqui RF, Liotta LA. Cancer. 1997;80:1529–1537. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971015)80:8+<1529::aid-cncr2>3.3.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liotta LA, Kohn EC. Nat Genet. 2003;33:10–11. doi: 10.1038/ng0103-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caceres G, Zhu XY, Jiao JA, Zankina R, Aller A, Andreotti P. Luminescence. 2003;18:218–223. doi: 10.1002/bio.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lopez JA, Andrews RK, Afshar-Kharghan V, Berndt MC. Blood. 1998;91:4397–4418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J, Fitzgerald ME, Berndt MC, Jackson CW, Gartner TK. Blood. 2006;108:2596–2603. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-011817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lopez JA, Leung B, Reynolds CC, Li CQ, Fox JEB. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12851–12859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]