Abstract

Mapping sites within the genome that are hypersensitive to digestion with DNaseI is an important method for identifying DNA elements that regulate transcription. The standard approach to locating these DNaseI-hypersensitive sites (DHSs) has been to use Southern blotting techniques, although we, and others, have recently published alternative methods using a range of technologies including high-throughput sequencing and genomic array tiling paths. In this article, we describe a novel protocol to use real-time PCR to map DHS. Advantages of the technique reported here include the small cell numbers required for each analysis, rapid, relatively low-cost experiments with minimal need for specialist equipment. Presented examples include comparative DHS mapping of known TAL1/SCL regulatory elements between human embryonic stem cells and K562 cells.

INTRODUCTION

Mapping the location of DNaseI-hypersensitive sites (DHSs) remains central to developing our understanding of transcriptional regulation. Elements with a range of transcriptional regulatory functions have been identified initially as DHSs. These include transcriptional enhancers (1,2) and repressors (3,4) as well as chromatin insulators and barrier elements (5,6). A number of techniques have been published recently that permit the mapping of DHSs without the need for Southern blotting (7–13). These include high-throughput sequencing of cloned DNA libraries derived from DNaseI-digested chromatin (8,9), and a number of different approaches that use genomic tiling path arrays to map DHSs (7,11,13). While these approaches have the advantage of covering large genomic regions with a limited number of experiments, they are inherently costly and less applicable to the rapid DHS mapping of specific genomic sites in a range of cell types.

An alternative approach that does permit the targeted semi-quantitative DHS mapping of specific loci has used quantitative real-time PCR to map sites from digested DNA (10). This technique depends on the quantification of relative loss of PCR signal observed when PCR primers amplify across regions of digested DNA compared with amplification of undigested DNA. This approach has been reported as showing good sensitivity, but a limitation is the large number of PCR reactions required to quantify the calculated loss of signal with significant certainty. In this article, we present an alternative method to identify DHS using real-time PCR by adapting the protocol we have used to map DHS using genomic tiling path arrays (11). We have previously demonstrated the high sensitivity and specificity of the basic protocol with regard to identifying DHS across large genomic regions (11). Here, we detail the laboratory protocol that permits the rapid comparative mapping of known and candidate DHS between different cell types using real-time PCR. As examples, we include comparative DHS mapping of regulatory elements located across the extended TAL1 (T-cell acute lymphocytic leukaemia-1, also known as SCL (stem cell leukaemia)) locus in human embryonic stem (hES) cells and the leukaemia cell line K562.

RESULTS

Generating a library of DHSs

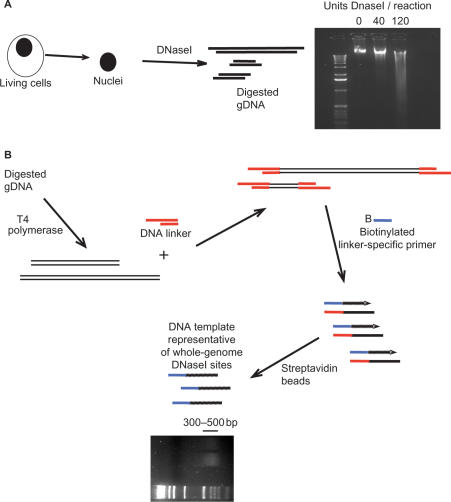

The basic protocol is outlined in Figure 1. Nuclei are extracted from living cells, then digested on ice for 1 h with a range of DNaseI concentrations, as detailed in the ‘Materials and methods’ sections. Following RNaseA and proteinaseK treatment, the DNA is extracted and run on a 1% agarose gel to check for the size of digested DNA. The gel in Figure 1A shows the DNA from mouse thymocyte nuclei digested with 0, 40 and 120 units of DNaseI. Maximal enrichment at DHS is usually observed with samples that are not over-digested. In the experiment shown, maximal enrichment at a known control DHS was seen with 40 units DNaseI (real-time PCR quantification shown in Figure 2B). The DNA is then blunt-ended using T4 polymerase (Figure 1B) and ligated with an asymmetric double-stranded linker. After extraction, DNA is amplified using a biotinylated linker-specific primer and 35 thermal polymerase cycles, as detailed in ‘Materials and methods’ section. As the linker will ligate to both ends of digested DNA, the amplification will represent a mix of primer extension and PCR, depending on the length of DNA amplified. As has been previously reasoned (13), one double strand of DNA in a region of DNaseI hypersensitivity is more likely to be digested twice within a short distance than non-hypersensitive DNA. This will lead to the preferential amplification of DNA from regions of DHS. The amplified DNA is then extracted using para-magnetic streptavidin beads, which provides a DNA library representative of whole-genome DHS. Agarose gel electrophoresis of the DNA recovered from the beads confirms that the vast majority of these products are between 300 and 500 base pairs in length (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Nuclei are isolated from cells, and aliquots are digested with a range of DNaseI as detailed in ‘Materials and methods’ section. The DNA is extracted and run on 1% agarose gels using gel electrophoresis (right panel). With the example shown, the 40-units sample gave maximal enrichment at a housekeeping promoter using the complete protocol. (B) The digested DNA is blunt-ended with T4 polymerase and ligated to the LP21–25 linker as detailed in ‘Materials and methods’ section. Following amplification with the biotinylated LP25 primer, the extracted DNA template represents a library of whole-genome DHS. When samples of this library are visualised using gel electrophoresis (bottom panel), the majority of products are between 300 and 500 bp in size.

Figure 2.

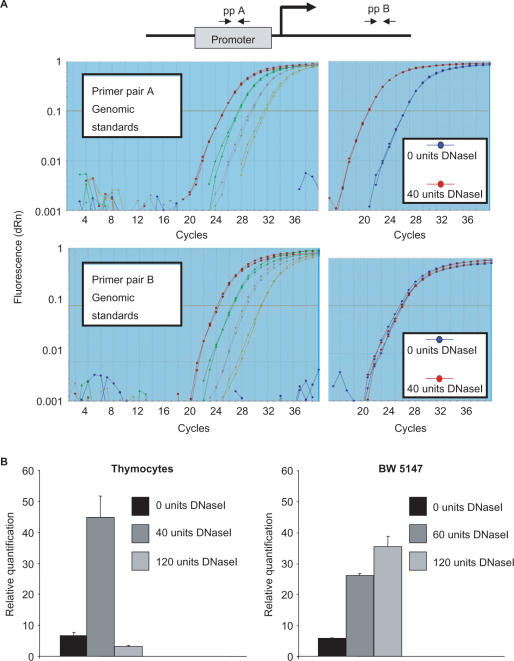

(A) The left-hand panels show the Sybr-green real-time PCR profiles (fluorescence versus cycle number) of 5-fold dilutions of quantified mouse genomic DNA standards for two primer pairs within (ppA) and 3′ (ppB) of the Stil promoter. The right-hand panel shows that DNA template derived from the 40 units DNaseI-treated sample amplified nearly six PCR cycles in advance of the 0 DNaseI-treated sample with ppA. No difference in amplification kinetics was seen between the 0 and 40 samples with ppB. (B) Quantification of samples relative to genomic standards using primers for the ‘housekeeping’ Hmbs promoter shows maximal enrichment with 40 units DNaseI treatment for primary mouse thymocytes (left panel) compared with maximal enrichment with 120 units DNaseI for the mouse T-cell line, BW5147 (right panel).

Real-time PCR quantification of DNA within the DHS library

Figure 2 documents the quantification of specific DNA sites from different mouse-cell-derived DNA libraries. Figure 2A shows the quantification of material from two primer sets, which are within (primer pair A) and 3′ (primer pair B) to the mouse Stil promoter. The left-hand panels of Figure 2A show the Sybr-green real-time fluorescence profiles using serial 5-fold dilutions of quantified mouse genomic DNA standards with primers A and B. A calculated standard curve then permits the quantification of DNA from this sequence in library samples. The right-hand panels of Figure 2A show the quantification of samples from 0 and 40 units DNaseI-treated material using primers A and B. While there is no difference in amplification between the samples using primer pair B, with primer pair A, the 40 units DNaseI sample amplifies ∼5.5 PCR cycles before the 0 units sample. This equates to greater than 40-fold enrichment at the Stil promoter compared with no observed enrichment downstream of the promoter. Figure 2B shows the quantifiable differences in enrichment at the porphobilinogen deaminase (Hmbs) promoter between primary mouse thymocytes and the mouse T-cell line BW5147. This representative primary mouse cell experiment was performed with the DNA shown in Figure 1A, which confirms that with these cells, maximal enrichment is observed from DNA that is not over-digested. The comparison of the thymocytes with the BW5147 cells illustrates another common finding that, in our experience of primary cell experiments, maximal enrichment is often obtained using lower amounts of DNaseI compared with cell lines.

Comparison of real-time PCR DHS with Southern blotting

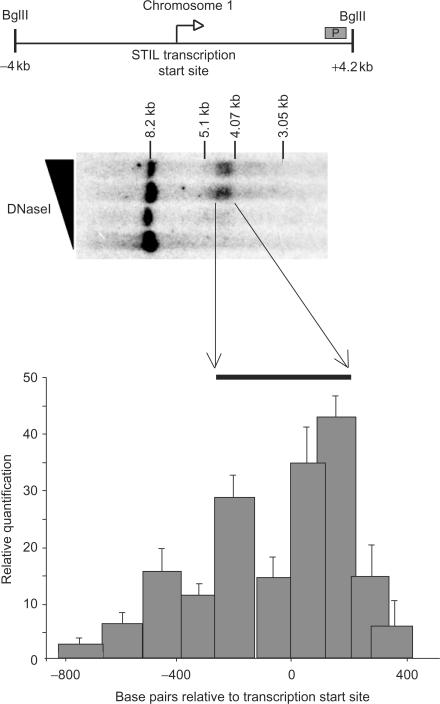

As the protocol generates template by primer extending away from a DNaseI-digestion site, as well as PCR amplification between DNaseI-digestion sites, there is the potential for the genomic size of the real-time DHS to be larger than sites revealed by Southern blotting. There is also potential for signal to be lost at the most ‘open’ stretch of DNA, due to over-digestion with DNaseI. These issues are addressed in Figure 3. The upper panel shows a Southern blot of the human STIL (SCL/TAL1 interrupting locus) promoter in K562 cells. The BglII restricted fragment is probed from the 3′ end, as shown in the upper panel. This reveals a central DHS ∼500 bp wide, with a suggestion of weaker hypersensitivity for a few hundred base pairs 5′ and 3′ to the central region. The lower panel shows real-time PCR data from K562 material using 10 primer sets, each generating an amplicon ∼120 bp long. This permits the quantification of enrichments over 1200 bp, centred around the STIL transcription start site. The lower panel represents the mean ± SD enrichment from three independent biological replicates from K562 cells. The black bar denotes the location of the ‘core’ hypersensitive site as defined by Southern blotting. There is good correlation between the location of the DHS between the two techniques. The 5′ extension of enrichment seen in the lower panel appears to reflect the weaker 5′ extension seen in the Southern blot in the upper panel. A dip in enrichment is observed in the lower panel over the previously mapped transcription-factor-binding sites (14), which may represent over-digestion of the most accessible core region of the DHS.

Figure 3.

The upper panel shows a Southern blot DHS map of the human STIL promoter in K562 cells using a 3′ probe (grey box labelled ‘P’) to analyse the BglII-restricted fragment (cut −4 kb and +4.2 kb relative to the STIL transcription start site). This revealed a core DHS ∼500 bp wide. The lower panel represents the mean ± SD real-time PCR quantification of enrichments from three biological replicates of K562 material relative to known genomic standards, using 10 separate primer sets that together amplify ∼1200 bp centred around the STIL transcription start site. The black bar represents the approximate location of the DHS, as identified by the Southern blot experiment in the upper panel. The real-time PCR amplification profile closely represents the Southern blot profile, although a central dip in real-time PCR signal is observed over the site of transcription factor binding.

Quantification of DHS across the TAL1 locus in hES and K562 cells

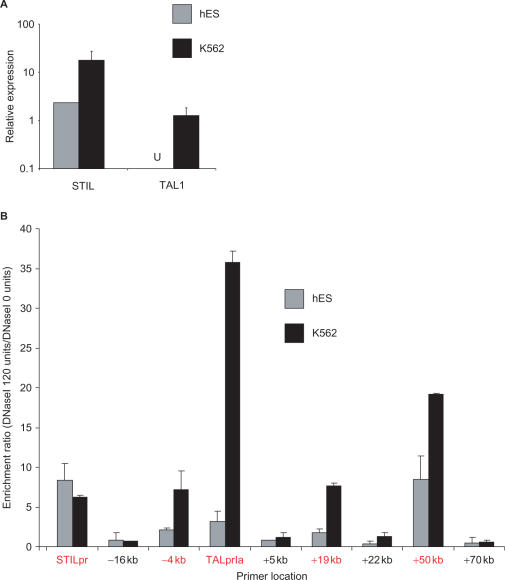

As examples of relative enrichments at different regulatory elements, we present a comparison of enrichments across the extended TAL1 locus from human embryonic stem (hES) cells and K562 cells in Figure 4B. Relative quantification of mRNA expression using real-time PCR shows that both of these cell types express STIL, but only K562 cells express TAL1 (Figure 4A). TAL1 expression is critical to the establishment of haematopoiesis in a developing embryo (15). Post embryogenesis, TAL1 expression is maintained in the non-lymphoid haematopoietic system, although in addition, expression is observed in a range of non-haematopoietic tissues, including endothelium and brain (16–18). Over the past 10 years, we and others have dissected the regulatory elements that direct the expression of TAL1 to different tissues (11,19–31). These include the 3′ haematopoietic stem cell enhancer (+19) (24,30), the 5′ endothelial-haematopoietic enhancer (−4) (31), the 3′ erythroid enhancer (+40 in mouse, +50 in human) (28), and a number of neuronal elements (25,26). The location of the STIL promoter has been previously mapped (14), although no other STIL regulatory elements have yet been identified.

Figure 4.

(A) Quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR quantification of STIL and TAL1 expression in hES and K562 cells. Expression was normalised to β-actin and plotted as detailed in ‘Materials and methods’ section. Both cell types express STIL, but TAL1 transcripts were not detectable (U) in hES cells. (B) Quantitative real-time PCR DNaseI profiles from hES and K562 cells using nine primer sets across the TAL1 locus. Primer set numbers refer to approximate kilobases (kb) relative to the start of TAL1 exon 1a. Primer sets corresponding to known regulatory elements are highlighted in red. Profiles represent the mean ± SD enrichment of material derived from two independent hES cell biological replicates, and two independent K562 cell cultures. Each bar represents the mean ratio of enrichment obtained from DNaseI-treated samples versus DNaseI-untreated samples for each cell type. With both cell types, no enrichment is seen at the four control sites (−16, +5, +22, +70 kb). K562 cells show maximal enrichments at the TAL1 regulatory elements and the STIL promoter, while hES cells show the highest enrichments at the STIL promoter and +50 enhancer, with minimal enrichment at the other TAL1 regulatory elements.

Figure 4B shows the mean ± SD ratio (DNaseI-treated enrichment/DNaseI-untreated enrichment) of quantitative enrichments from two independent hES cell biological replicates and two independent K562 biological replicates, using primer sets from different locations as indicated in the figure. Primers indicated in red correspond to known regulatory elements. The hES cell cultures were maintained as detailed in methods. Both cell types show significant enrichment at the STIL promoter. Four control regions were selected: −16 kb, upstream of TAL1; +5 and +22 kb, within the TAL1 locus; +70 kb, downstream of TAL1. These sequences were chosen as control regions as they show limited homology between a number of species (26) and were considered highly unlikely to represent regulatory elements. All four regions showed no enrichments between DNaseI-treated and -untreated samples in either the hES cells or K562 cells. The most striking differences between hES cells and K562 cells were found at the TAL1 regulatory elements. With K562 cells, there is prominent enrichment at the TAL1 promoter 1a, and the −4, +19 and +50 enhancers. These cells express high levels of TAL1 transcripts, and were originally derived from a patient with blastic transformation of chronic myeloid leukaemia. K562 cells are relatively undifferentiated, although they have a partial erythroid phenotype. This potentially explains the marked enrichment seen at the +19 stem cell enhancer and the +50 erythroid enhancer. This is similar to data obtained from primary mouse erythroid cells (day 14.5 foetal liver), which show the highest enrichments at the mouse +40 enhancer (homologous to the human +50) (data not shown). In contrast, the hES cells show markedly reduced enrichment at the TAL1 regulatory elements when compared with K562 cells. Although there is enrichment at the +50 enhancer, there is minimal enrichment at the −4, promoter 1A and +19 elements. Reduced/absent accessibility of regulatory elements to DNaseI digestion is consistent with the lack of expression of TAL1 in hES cells (Figure 4A). As ES cells differentiate to form embryoid bodies, expression of TAL1 is rapidly switched on, appearing from day 3 of mouse ES cell differentiation (32). The relative accessibility of the +50 enhancer may reflect a poised chromatin state in hES cells, which permits a rapid response to the changing transcription factor environment that accompanies differentiation.

DISCUSSION

The development of techniques that permit the rapid comparative mapping of DHS between different cell types will greatly facilitate the study of transcriptional regulation in both normal and diseased cells. Recently published high-throughput techniques that map DHS sites using high-throughput sequencing (8,9) and genomic array tiling paths (7,11,13) have clear advantages of scale over more targeted approaches. Major disadvantages of these approaches include cost and lack of focus. This makes them less suitable for many laboratories that want to assess the chromatin accessibility of a number of defined or presumed regulatory elements in a range of cell types. A real-time-PCR-based approach to DHS mapping has, therefore, a number of potential advantages for researchers interested in specific regulatory questions at defined loci. Real-time PCR is relatively inexpensive compared with the large-scale techniques, and permits a rapid, focused DHS analysis of defined regions of DNA from multiple cell types. It also provides flexibility, as any genomic region can be analysed from the DNA library derived from the DNaseI-treated samples by designing further real-time PCR primer sets.

We have previously shown that our basic technique for amplifying a library of DHS generates a template representative of known DHS with excellent sensitivity and specificity (11). Although the experiments presented in this paper were each performed using 5 million cells/digestion condition, we have obtained reproducible data using 5-fold fewer cells as starting material. We feel our technique can deliver acceptable specificity and sensitivity for DHS mapping with small numbers of cells, and will therefore be of use to those researchers working with limited numbers of primary cells. An alternative approach using real-time PCR to define DHS has been previously published (10). The two approaches differ in that Dorscher et al. quantify the DHS through the loss of PCR signal obtained from DHS when DNA is digested, whereas our approach uses real-time PCR to quantify a gain of signal observed from DHS. Dorscher et al. report excellent sensitivity using their approach to map DHS. However, the technique depends on large numbers of comparative quantitative real-time PCR reactions across a region in both digested and undigested material, in order to quantify the loss of enrichment. One advantage of our technique published here is that data can be obtained using far fewer quantitative PCR reactions. The technique is highly reproducible, with relatively little variation in quantifiable enrichments observed between different biological replicates. Moreover, we demonstrate tissue specificity, with variable enrichment at known regulatory elements between different cell types.

The technique published here permits the rapid comparative analysis of DHS between different cell types from relatively small numbers of cells. It will have potential use for researchers across a broad spectrum of biology for the study of transcriptional regulation in both healthy and diseased tissues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Cell lines were maintained in culture as previously described (11). Care was taken to ensure maximum viability of cells when taken for experiments. The primary thymocytes used for Figure 2 were prepared by gentle physical disassociation of a whole thymus gland into PBS supplemented with 2% FCS. Cells were filtered to ensure that a single-cell suspension was taken forward for nuclei isolation. Human embryonic stem cells (hES) were grown in chemically defined media in the presence of Activin and FGF2, as detailed previously (33). In these conditions, hES cells remain homogenously undifferentiated.

Nuclei preparation

Up to 3 × 107 cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and resuspended in 2 ml of ice-cold cell lysis buffer [300 mM sucrose, 10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 15 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl, 0.1 mM EGTA, 60 mM KCl, 0.2% NP-40, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 μM spermidine, 1× protease inhibitor (complete, Roche)]. After 5 min, the lysed cells were spun at 500 g for 5 min at 4°C with brakes off. After careful removal of supernatant, the nuclei were gently resuspended in 200 μl of ice-cold reaction buffer (20 μl 10× DNaseI buffer, 4 μl glycerol, 176 μl water) using pipette tips with cut off ends. The nuclei were spun again at 500 g for 5 min at 4°C and, following supernatant removal, were resuspended in 30 μl of reaction buffer per DNaseI condition. For example, if 2 × 107 cells were taken to look at four different conditions (e.g. 0, 20, 60, 120 units DNaseI), the nuclei were resuspended in 120 μl of reaction buffer. Separate 30 μl aliquots were then taken and gently mixed with 70 μl of DNaseI mix (see Table 1) on ice. This made a final digestion volume of 100 μl for each sample, which was left to incubate for 1 h on ice in the cold room.

Table 1.

DNaseI mixes of 70 μl aliquots were prepared as detailed

| DNaseI condition (units) | 0 | 20 | 60 | 120 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10× DNaseI buffer (μl) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| DNaseI (2 U/μl) (Ambion) (μl) | 0 | 10 | 30 | 60 |

| Water (μl) | 63 | 53 | 33 | 3 |

The resuspended nuclei were added as 30 μl aliquots to make a final digestion volume of 100 μl.

After 1 h, 700 μl of nuclei lysis buffer (100 mM tris HCL pH 8, 5 mM EDTA pH 8, 200 mM NaCl, 0.2% SDS) was added to each sample with 50 μg proteinase K. Following gentle mixing with inversion, the lysed samples were incubated at 55°C for 1 h. RNaseA (10 μg (Ambion)) was then added to each sample and further incubated at 37°C for 30 min. DNA was then extracted using standard phenol–chloroform techniques. Care was taken to use cut-off tips and very gentle pipetting to reduce non-specific DNA sheering. Following precipitation, DNA was resuspended in 200 μl of 0.1 TE and quantified using spectophotometry. Samples (1 μg) were analysed using gel-electrophoresis, as shown in Figure 1A.

DNA library preparation

Following quantification, 7.5 μg of DNA was taken for each sample condition. This was blunt-ended using T4 polymerase (10 μl 10× buffer, 0.5 μl 25 mM dNTP, 3 μl BSA, 1 μl T4 polymerase (3 U/μl NE Biolabs), 85.5 μl of water/DNA in 0.1 TE). The samples were mixed gently on ice, then put at 12°C for 16 min. The reaction was stopped with excess EDTA (4 μl 0.5 M) followed by 75°C for 10 min. The DNA was further extracted using phenol–chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. Glycogen carrier (5 μg) was used at this stage, and the pellet resuspended in 80 μl water.

The blunt-ended DNA was then ligated to the LP21–25 linker. A stock of linker was prepared by mixing 80 μl LP21 (100 μM: GAATTCAGATCTCCCGGGTCA) with 80 μl LP25 (100 μM: GCGGTGACCCGGGAGATCTG AATTC) and 240 μl water. The mix was then placed on a 95°C hot block and the power supply turned off. When the block had cooled to room temperature, the LP21–25 linker was aliquoted and frozen. The 80 μl DNA sample was split into two samples for ligation (5 μl 10× buffer, 3 μl LP21–25 linker, 3 μl ligase (NE biolabs 400 U/μl and 39 μl DNA). This was mixed well with a pipette and left at 16°C overnight.

Following ligation, the DNA was precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended in 42 μl water. The sample was amplified using Vent exo-polymerase and a biotinylated LP25 primer. The mix (5 μl ThermoPol 10× buffer, 0.5 μl B-LP25 (200 μM), 2 μl Vent exo-(NE Biolabs 2 U/μl), 1 μl dNTP (25 mM) and 41.5 μl DNA) was amplified with the following thermal cycle: (95°C 3 min, 95°C 30 s, 61°C 30 s, 72°C 30 s) × 35 cycles.

Following amplification, the biotinylated products were extracted using Dynal streptavidin beads. For each sample, 30 μl of beads (Dyabeads M-270; Dynal biotech) were washed twice in 2× binding buffer (10 mM Tris HCL pH7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 2 M NaCl) using a magnet, and then resuspended in 50 μl of 2× binding buffer/sample. Each post amplification sample (50 μl) was then mixed with 50 μl of resuspended beads and incubated at room temperature on a rotator for 1 h. After binding, the samples were washed twice with 2× binding buffer, then once with 1× TE. After the last wash, each sample was resuspended in 30 μl 0.1 TE. The paired samples that were split before ligation were then pooled, making a 60 μl final aliquot. This was heated at 95°C for 10 min to free the DNA from the beads, and then stored at 4°C.

Real-time PCR quantification

We have used Stratagene Brilliant SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix as our standard kit for quantification of genomic controls and samples. We have used a range of primer sets. The HMBS primers are: human—Forward; ATGCTGCCTATTTCAAGGTTGT, Reverse; GAATT GGAACATTGCGACAGT, and mouse—Forward; CGGAGTCATGTCCGGTAAC, Reverse; CGACCAA TAGACGACGAGAA. Primers from the TAL1 locus (human and mouse) are available on request.

Amplification conditions and PCR mixes were as recommended by Stratagene. Genomic standard curves were calculated for each primer using serial 5-fold dilutions from 50 ng genomic DNA/PCR reaction. For each sample PCR, a 45 μl stock was made using 1.3 μl of sample DNA + 43.7 μl water. This stock was used as 5 μl per real-time PCR reaction, and following amplification, quantified relative to the genomic DNA standard curve, for each primer set. The quantifications shown in Figure 3 represent the absolute quantification of DNA at each primer set for the 5 μl PCR sample.

The mRNA expression levels of TAL1 and STIL in Figure 4A were normalised relative to β-actin and plotted relative to mRNA expression from normal human donor CD34 + cells, as described previously (11).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

GAF is a Leukaemia Research Fund (LRF) Bennett Fellow. Work in BG's laboratory is supported by the LRF and ARG's laboratory is supported by the LRF and the Wellcome Trust. Funding to pay the open Access publication charge was provided by the Wellcome Trust.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Follows GA, Tagoh H, Lefevre P, Hodge D, Morgan GJ, Bonifer C. Epigenetic consequences of AML1-ETO action at the human c-FMS locus. EMBO J. 2003;22:2798–2809. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vyas P, Vickers MA, Simmons DL, Ayyub H, Craddock CF, Higgs DR. Cis-acting sequences regulating expression of the human alpha-globin cluster lie within constitutively open chromatin. Cell. 1992;69:781–793. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90290-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawada S, Scarborough JD, Killeen N, Littman DR. A lineage-specific transcriptional silencer regulates CD4 gene expression during T lymphocyte development. Cell. 1994;77:917–929. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansel KM, Greenwald RJ, Agarwal S, Bassing CH, Monticelli S, Interlandi J, Djuretic IM, Lee DU, Sharpe AH, et al. Deletion of a conserved Il4 silencer impairs T helper type 1-mediated immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:1251–1259. doi: 10.1038/ni1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mutskov VJ, Farrell CM, Wade PA, Wolffe AP, Felsenfeld G. The barrier function of an insulator couples high histone acetylation levels with specific protection of promoter DNA from methylation. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1540–1554. doi: 10.1101/gad.988502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung JH, Whiteley M, Felsenfeld G. A 5′ element of the chicken beta-globin domain serves as an insulator in human erythroid cells and protects against position effect in Drosophila. Cell. 1993;74:505–514. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80052-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawford GE, Davis S, Scacheri PC, Renaud G, Halawi MJ, Erdos MR, Green R, Meltzer PS, Wolfsberg TG, et al. DNase-chip: a high-resolution method to identify DNase I hypersensitive sites using tiled microarrays. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:503–509. doi: 10.1038/NMETH888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford GE, Holt IE, Mullikin JC, Tai D, Blakesley R, Bouffard G, Young A, Masiello C, Green ED, et al. Identifying gene regulatory elements by genome-wide recovery of DNase hypersensitive sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:992–997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307540100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crawford GE, Holt IE, Whittle J, Webb BD, Tai D, Davis S, Margulies EH, Chen Y, Bernat JA, et al. Genome-wide mapping of DNase hypersensitive sites using massively parallel signature sequencing (MPSS) Genome Res. 2006;16:123–131. doi: 10.1101/gr.4074106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorschner MO, Hawrylycz M, Humbert R, Wallace JC, Shafer A, Kawamoto J, Mack J, Hall R, Goldy J, et al. High-throughput localization of functional elements by quantitative chromatin profiling. Nat. Methods. 2004;1:219–225. doi: 10.1038/nmeth721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Follows GA, Dhami P, Gottgens B, Bruce AW, Campbell PJ, Dillon SC, Smith AM, Koch C, Donaldson IJ, et al. Identifying gene regulatory elements by genomic microarray mapping of DNaseI hypersensitive sites. Genome Res. 2006;16:1310–1319. doi: 10.1101/gr.5373606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabo PJ, Humbert R, Hawrylycz M, Wallace JC, Dorschner MO, McArthur M, Stamatoyannopoulos JA. Genome-wide identification of DNaseI hypersensitive sites using active chromatin sequence libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:4537–4542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400678101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sabo PJ, Kuehn MS, Thurman R, Johnson BE, Johnson EM, Cao H, Yu M, Rosenzweig E, Goldy J, et al. Genome-scale mapping of DNase I sensitivity in vivo using tiling DNA microarrays. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:511–518. doi: 10.1038/nmeth890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aplan PD, Lombardi DP, Kirsch IR. Structural characterization of SIL, a gene frequently disrupted in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1991;11:5462–5469. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robb L, Lyons I, Li R, Hartley L, Kontgen F, Harvey RP, Metcalf D, Begley CG. Absence of yolk sac hematopoiesis from mice with a targeted disruption of the scl gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:7075–7079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Eekelen JA, Bradley CK, Gothert JR, Robb L, Elefanty AG, Begley CG, Harvey AR. Expression pattern of the stem cell leukaemia gene in the CNS of the embryonic and adult mouse. Neuroscience. 2003;122:421–436. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00571-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drake CJ, Brandt SJ, Trusk TC, Little CD. TAL1/SCL is expressed in endothelial progenitor cells/angioblasts and defines a dorsal-to-ventral gradient of vasculogenesis. Dev. Biol. 1997;192:17–30. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gering M, Rodaway AR, Gottgens B, Patient RK, Green AR. The SCL gene specifies haemangioblast development from early mesoderm. EMBO J. 1998;17:4029–4045. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Begley CG, Robb L, Rockman S, Visvader J, Bockamp EO, Chan YS, Green AR. Structure of the gene encoding the murine SCL protein. Gene. 1994;138:93–99. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90787-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bockamp EO, McLaughlin F, Murrell A, Green AR. Transcription factors and the regulation of haemopoiesis: lessons from GATA and SCL proteins. Bioessays. 1994;16:481–488. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bockamp EO, McLaughlin F, Murrell AM, Gottgens B, Robb L, Begley CG, Green AR. Lineage-restricted regulation of the murine SCL/TAL-1 promoter. Blood. 1995;86:1502–1514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bockamp EO, McLaughlin F, Gottgens B, Murrell AM, Elefanty AG, Green AR. Distinct mechanisms direct SCL/tal-1 expression in erythroid cells and CD34 positive primitive myeloid cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:8781–8790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottgens B, McLaughlin F, Bockamp EO, Fordham JL, Begley CG, Kosmopoulos K, Elefanty AG, Green AR. Transcription of the SCL gene in erythroid and CD34 positive primitive myeloid cells is controlled by a complex network of lineage-restricted chromatin-dependent and chromatin-independent regulatory elements. Oncogene. 1997;15:2419–2428. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez M, Gottgens B, Sinclair AM, Stanley M, Begley CG, Hunter S, Green AR. An SCL 3′ enhancer targets developing endothelium together with embryonic and adult haematopoietic progenitors. Development. 1999;126:3891–3904. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinclair AM, Gottgens B, Barton LM, Stanley ML, Pardanaud L, Klaine M, Gering M, Bahn S, Sanchez M, et al. Distinct 5′ SCL enhancers direct transcription to developing brain, spinal cord, and endothelium: neural expression is mediated by GATA factor binding sites. Dev. Biol. 1999;209:128–142. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gottgens B, Barton LM, Gilbert JG, Bench AJ, Sanchez MJ, Bahn S, Mistry S, Grafham D, McMurray A, et al. Analysis of vertebrate SCL loci identifies conserved enhancers. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:181–186. doi: 10.1038/72635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gottgens B, Barton LM, Chapman MA, Sinclair AM, Knudsen B, Grafham D, Gilbert JG, Rogers J, Bentley DR, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the stem cell leukemia gene (SCL)-comparative analysis of five vertebrate SCL loci. Genome Res. 2002;12:749–759. doi: 10.1101/gr.45502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delabesse E, Ogilvy S, Chapman MA, Piltz SG, Gottgens B, Green AR. Transcriptional regulation of the SCL locus: identification of an enhancer that targets the primitive erythroid lineage in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:5215–5225. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.5215-5225.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silberstein L, Sanchez MJ, Socolovsky M, Liu Y, Hoffman G, Kinston S, Piltz S, Bowen M, Gambardella L, et al. Transgenic analysis of the SCL + 19 stem cell enhancer in adult and embryonic haematopoietic and endothelial cells. Stem Cells. 2005 doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gottgens B, Nastos A, Kinston S, Piltz S, Delabesse EC, Stanley M, Sanchez MJ, Ciau-Uitz A, Patient R, et al. Establishing the transcriptional programme for blood: the SCL stem cell enhancer is regulated by a multiprotein complex containing Ets and GATA factors. EMBO J. 2002;21:3039–3050. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gottgens B, Broccardo C, Sanchez MJ, Deveaux S, Murphy G, Gothert JR, Kotsopoulou E, Kinston S, Delaney L, et al. The scl + 18/19 stem cell enhancer is not required for hematopoiesis: identification of a 5′ bifunctional hematopoietic-endothelial enhancer bound by Fli-1 and Elf-1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:1870–1883. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.5.1870-1883.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung YS, Zhang WJ, Arentson E, Kingsley PD, Palis J, Choi K. Lineage analysis of the hemangioblast as defined by FLK1 and SCL expression. Development. 2002;129:5511–5520. doi: 10.1242/dev.00149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vallier L, Alexander M, Pedersen RA. Activin/Nodal and FGF pathways cooperate to maintain pluripotency of human embryonic stem cells. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:4495–4509. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]