Abstract

Galectin-3, a multifunctional β-galactoside-binding lectin, is known to participate in development, oncogenesis, cell-to-cell attachment, and inflammation. We studied to determine whether galectin-3 is associated with cell injury and regeneration in two types of acute renal failure (ARF), namely ischemic and toxic ARF. In ischemia/reperfusion renal injury in rats (bilateral renal pedicles clamped for 40 minutes), galectin-3 mRNA began to increase at 2 hours and extended by 6.2-fold at 48 hours (P < 0.01 versus normal control rats), and then decreased by 28 days after injury. In addition, a significant negative correlation between galectin-3 mRNA expression and serum reciprocal creatinine was shown at 48 hours after injury (n = 13, r = −0.94, P < 0.0001). In folic acid-induced ARF, galectin-3 mRNA was found to be up-regulated at 2 hours after injury and increased levels continued until at least 7 days post-injury. In immunohistochemistry, at 2 hours following reperfusion, galectin-3 began to develop in proximal convoluted tubules. From 6 hours up to 48 hours, galectin-3 was also found in proximal straight tubules, distal tubules, thick ascending limbs, and collecting ducts. In later stages of regeneration, galectin-3 expressions were found in macrophages. In conclusion, we demonstrated that galectin-3 expressions were markedly up-regulated in both ischemic and toxic types of ARF. Galectin-3 may play an important role in acute tubular injury and the following regeneration stage.

Lectins bind specific oligosaccharide structures on glycoproteins and glycolipids, and several families of them have been identified. The galectins comprise a family of β-galactoside-binding lectins, over ten members of which are currently known, and are widely distributed from lower invertebrates to mammals. 1-3 All galectins studied lack a signal sequence for insertion into endoplasmic reticulum, and thus they are secreted from the cell via a nonclassical pathway. 4,5 Galectin-3 was originally described as an antigen on the surface of murine thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages. Its molecular weight ranges from 30 to 42 kd, depending on the species. The galectin-3 has a unique amino-terminal domain, a highly conserved repetitive sequence rich in proline and glycine, and a carboxyl-terminal domain containing the carbohydrate recognition site. 1,6-8 It was found to be expressed by several inflammatory cells as well as macrophages, including basophils, mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils. 9,10 Exogenously added lectin has been shown to stimulate the secretion of cytokines and other factors by such cells, suggesting roles in autocrine cytokine regulation in inflammatory cells. 11,12 In addition, galectin-3 is also expressed by epithelial cells in a variety of organs including kidney. 13,14 It is found on the cell surface and within the extracellular matrix, as well as in the cytoplasm and the nucleus of cells. The distribution in many different types of cells, together with varied subcellular localization, indicates galectin-3 has many different roles in normal and pathophysiological conditions. In fact, the expression pattern of galectin-3 varies during organ development including nephrogenesis. 14 It is known that this pattern is also changed in breast, colon, prostate, and thyroid carcinomas as well as in inflammatory lesions. 15-18 Galectin-3 has been suggested to be involved in mitosis and proliferation, and also to play a role in intracellular pre-mRNA splicing. 19-21 On the cell surface, it mediates cell-cell adhesion and cell-matrix interaction via binding to its complementary glycoconjugates, such as laminin and fibronectin, and thereby most probably plays an important role in the pathogenesis of metastasis. 22-25 Alternatively, galectin-3 was found to have significant sequence similarity with bcl-2 and might be associated with apoptosis. 26,27 Despite the well-known information described above, few data are available concerning its pathophysiological role in renal injury.

Acute renal failure (ARF) is a common renal disease. Treatments, including renal replacement therapy, have been greatly advanced. Nevertheless, the high mortality of patients with ARF has not changed over the last decades. Moreover, the number of patients with ARF is increasing as a result of more advanced medical treatments and more arduous surgical interventions in older and complicated patients. 28 The main causes of ARF are well known to be ischemia and nephrotoxic insult. Although extensively investigated, the underlying mechanisms, which comprise cell injury, cell death, and regeneration, are not clearly delineated. Recently, apoptosis has been known to play an important role in ARF. 29,30 On the other hand, it is presumed that inflammatory cascade participates in ARF. 31 In addition, the regenerating kidney assumes an earlier developmental stage and a less mature phenotype, which involve the up-regulation of a group of genes. Some kinds of growth factor genes and proto-oncogenes are observed to increase and are suggested to have a role in the recovery process. 32,33 As mentioned above, galectin-3 has been found to be associated with cell-cell adhesion, cell-matrix interaction, inflammatory cytokines, and apoptosis, all of which have been recently proposed to be involved in ARF. Therefore, we hypothesized that this multifunctional protein, galectin-3, might play a role in the pathophysiology of ARF and its expression changed in the process.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g) were purchased from SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). All animals had free access to water and food. Animal care followed the criteria of the National Defense Medical College for the care and use of laboratory animals in research.

Ischemia/Reperfusion Renal Injury and Experimental Protocol

Rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium. The animals were placed on a heating pad kept at 37°C to maintain constant body temperature. A midline incision was then made, and bilateral renal pedicles were clamped for 40 minutes. Both kidneys were carefully inspected for ischemic change 2 minutes after the clamping. To reduce functional renal injury during surgical manipulations, the abdominal contents were returned and 1 ml of prewarmed normal saline was instilled into the abdominal cavity. Then the abdomen was covered with gauze pre-immersed in warm saline. After 40 minutes, the declamped rats were again inspected to see if reperfusion was well achieved, and thereafter the abdominal cavity was closed. The rats were sacrificed at 2, 6, 24, or 48 hours or 7, 14, or 28 days after reperfusion (n = 4 to 11). As a control, sham operation was performed in an identical manner without renal pedicle clamping. Animals of sham operation group were sacrificed at 24 and 48 hours after laparotomy (n = 4 respectively). At the time of sacrifice, blood was obtained for measurement of serum creatinine, and both kidneys were harvested for histological study or RNA analysis.

Folic Acid Administration and Experimental Protocol

Folic acid-induced ARF was made according to the previous report. 34 Briefly, folic acid was dissolved in 0.25 mol/L sodium bicarbonate (120 mg of folic acid per milliliter) and injected intraperitoneally (450 mg/kg). The rats were sacrificed at 2, 6, 24, 48 hours or 7 days after injection (n = 4 in each group). As a control, sham group received an injection of 0.25 mol/L sodium bicarbonate without folic acid into abdominal cavity. Animals of sham group were sacrificed at 24 and 48 hours after sham injection (n = 4 in each group). At the time of sacrifice, blood was obtained for measurement of serum creatinine, and both kidneys were harvested for histological examination and RNA analysis.

Complementary RNA (cRNA) Probe and RNase Protection Assay (RPA)

An 832-bp rat galectin-3 complementary DNA (cDNA; −1–831 from ATG) was obtained with reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from total RNA extracted from whole kidney of adult rats. We used 5′-AATGGCAGACGGCTTCTCACTT-3′ as the forward primer and 5′-TAACACACAGGGCAGTTCTGGT-3′ as the reverse. 35 The cDNA was cloned into pGEM-T-Easy plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI). The plasmid containing antisense cDNA behind T7 promoter was digested with ApaI following ligation with T4 ligase to give template DNA of appropriate size. Then it was linearized with EcoRI digestion and transcribed with T7-polymerase to give a 32P-cRNA probe with α-32P uridine 5′-triphosphate (ICN Biomedicals, Inc., Costa Mesa, CA). The size of this radiolabeled cRNA probe was 215 b and expected protected fragment was 195 b. A 100-bp (483–582 from ATG) fragment of rat glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA was obtained with RT-PCR and cloned into pBSIISK-plasmid (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The plasmid was linearized with BamHI digestion and transcribed with T7 polymerase to give a 265-b cRNA probe. Sequences of the probes were determined by the dideoxy chain termination method to confirm identity with the authentic cDNA sequences. The 32P-labeled RNAs of known length (597, 275, and 187 b) were prepared and used as size markers.

Total RNA was isolated from whole kidney, as previously described, and extracted with phenol/chloroform. 36 The RNA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically. The RNA purity was assessed by measuring the optical density ratio in both 260 and 280 nm. Five micrograms of RNA were subjected to mRNA determination with the RPA. Total RNA was dissolved in 20 μl hybridization buffer (400 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 40 mmol/L piperazine diethane sulfonic acid, pH 6.4, 80% formamide) containing 3 × 10 4 cpm galectin-3 cRNA probe and 1 × 10 4 cpm GAPDH probe and incubated at 65°C for 5 minutes, then at 55°C overnight. After hybridization, 150 μl digestion buffer composed of 300 mmol/L sodium acetate, 5 mmol/L EDTA, and 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 17.5 μg/ml RNase A and 175 U/ml RNase T1 (both from Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), was added to the reaction mixture and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. Then, 2.5 μl proteinase K (Boehringer Mannheim, 20 mg/ml) and 10 μl of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate were added and incubated at 37°C for an additional 15 minutes. The antisense RNA probes that were hybridized with galectin-3 or GAPDH mRNA formed a double-stranded structure and were protected from RNase digestion. The protected fragments were precipitated with ethanol and analyzed on an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 mol/L urea. After electrophoresis, the gels were dried and the mRNA level was determined with a BAS 2000 image analyzer (Fuji Photo Film Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), then exposed to Kodak X-Omat AR film (Eastman Kodak Co., Rochester, NY) for autoradiography.

Immunohistochemical Examination

Kidney sections obtained from normal, sham-operated, and ARF rats were examined by peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin-biotin immunocytochemistry using galectin-3 polyclonal rabbit antiserum provided by Dr. R. C. Hughes (National Institute for Medical Research, London, UK). It was raised against a synthetic peptide based on the repetitive sequence in the N-terminal domain of hamster galectin-3. He and his coworkers also prepared other antibodies raised against the recombinant carbohydrate recognition domain or the whole peptide of hamster galectin-3. Each antibody specifically identifies the Mr = 32,000 rat galectin-3 molecules and does not cross-react with other galectins. 37,38 Formalin (10%)-fixed and paraffin-embedded specimens were used for the immunohistochemical staining. Deparaffinized sections were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 20 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase. After blocking in 10% nonimmune serum for 10 minutes at room temperature, sections were incubated in a high-humidity chamber for 60 minutes at 37°C with galectin-3 polyclonal antiserum diluted 1:200. In some tissues, we compared the distribution of galectin-3 on serial sections with macrophage, using anti-rat macrophage monoclonal antibody clone ED-1 (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). The slides were washed with phosphate buffered saline for 15 minutes, followed by incubation for 10 minutes at room temperature with DAKO LSAB system link antibody (DAKO Corp., Carpinteria, CA). After washing for 15 minutes in phosphate buffered saline, the sections were incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature with DAKO LSAB system peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin. Finally, the sections were soaked in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, containing 20 mg/dl DAB, 0.003% hydrogen peroxide) for 5 to 7 minutes and counterstained with hematoxylin. Negative controls consisted of nonimmune rabbit serum or omission of the primary antibody.

Statistical Analyses

All data are shown as mean ± SEM. The significance of differences of the data was determined with analysis of variance techniques followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test for individual comparisons between group means. The correlation of the data was determined with Pearson’s test. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

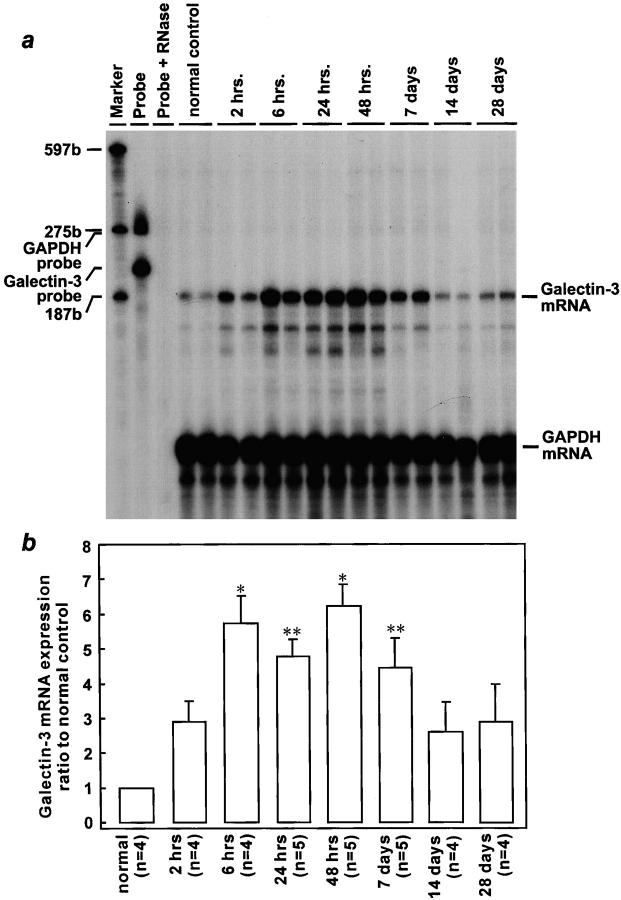

Rapid Induction of Galectin-3 mRNA after Ischemia/Reperfusion Renal Injury

Serum creatinine increased to an average of 3.23 ± 0.69 mg/dl at 48 hours after reperfusion, compared with mean values of 0.28 ± 0.06 mg/dl in the sham group (P < 0.01) and of 0.26 ± 0.06 mg/dl in the normal control group (P < 0.01), which indicated that animals whose renal pedicles were clamped developed severe ARF. No significant difference was shown in galectin-3/GAPDH mRNA ratio between normal and sham-operated rat kidneys at both 24 and 48 hours after sham operation. However, as shown in Figure 1 ▶ , galectin-3 mRNA was markedly increased in injured kidneys as compared with that in normal control. Time-course study revealed that galectin-3 mRNA developed as early as 2 hours after reperfusion (the earliest time point tested). Then, it was elevated progressively up to 48 hours following injury by 6.2-fold as compared with that in normal rats (P < 0.01). Although galectin-3 mRNA began to decrease gradually 7 days thereafter, the gene expression tended to vary between animals.

Figure 1.

Induction of galectin-3 mRNA expression in the rat kidney after ischemia/reperfusion injury. The representative autoradiogram (exposed for 12 days) is shown (a). Sizes of marker RNAs were indicated to the left. The amount of galectin-3 mRNA was normalized for GAPDH mRNA, and the results were expressed as ratio to normal control rats (b). Data are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.01 compared with control; **P < 0.05 compared with control.

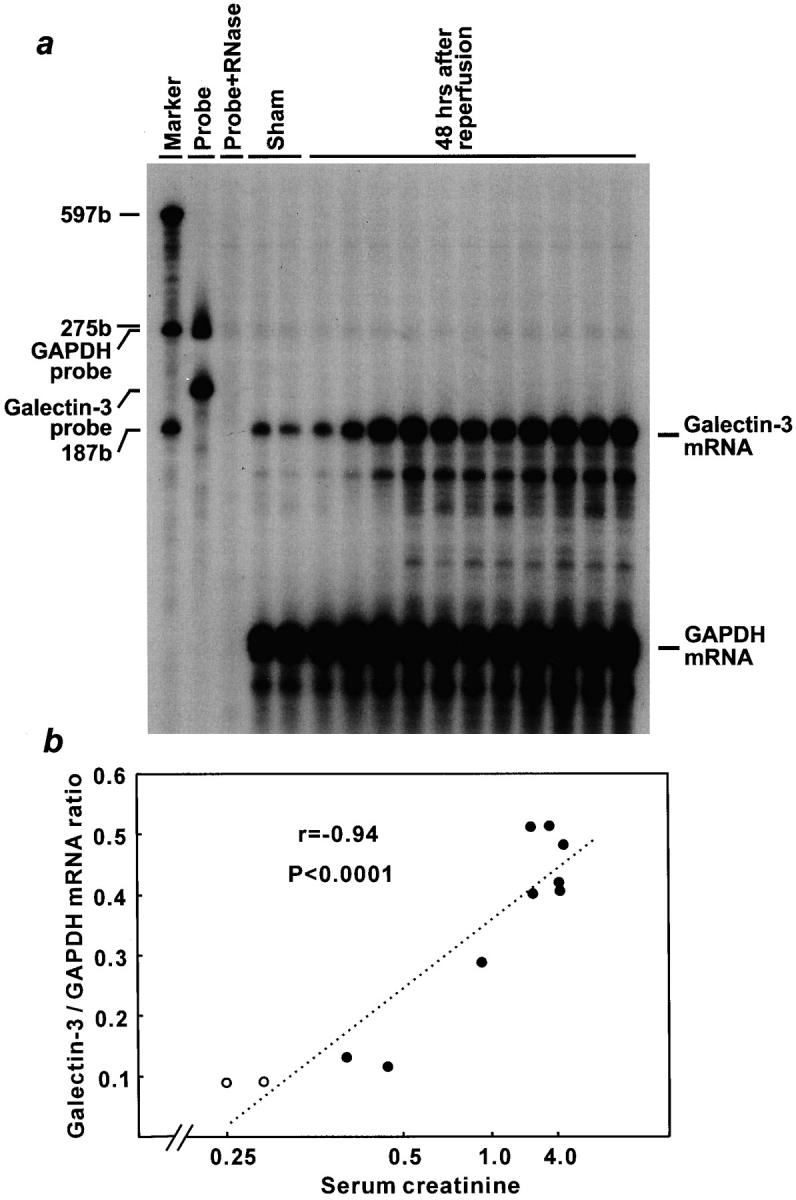

At 48 hours after reperfusion injury, the peak of galectin-3 mRNA expression, galectin-3/GAPDH mRNA ratio and serum reciprocal creatinine levels showed a highly significant negative correlation (n = 13, r = −0.94, P < 0.0001; Figure 2 ▶ ).

Figure 2.

Highly significant correlation between galectin-3 mRNA expression and renal dysfunction in ischemia/reperfusion injury. The amount of galectin-3 mRNA was normalized for GAPDH mRNA. a: Autoradiograph of RNase protection assay (exposed for 12 days); sham operated rats (lanes 1 and 2) and ARF rats after 48 hours reperfusion (lanes 3–13) were demonstrated in the order of serum creatinine levels. Sizes of marker RNAs were indicated to the left. b: Graphic presentation of correlation between renal function and galectin-3 mRNA expression. The horizontal axis showed serum creatinine level in order of its reciprocal. ○, sham operated rats; •, ARF rats.

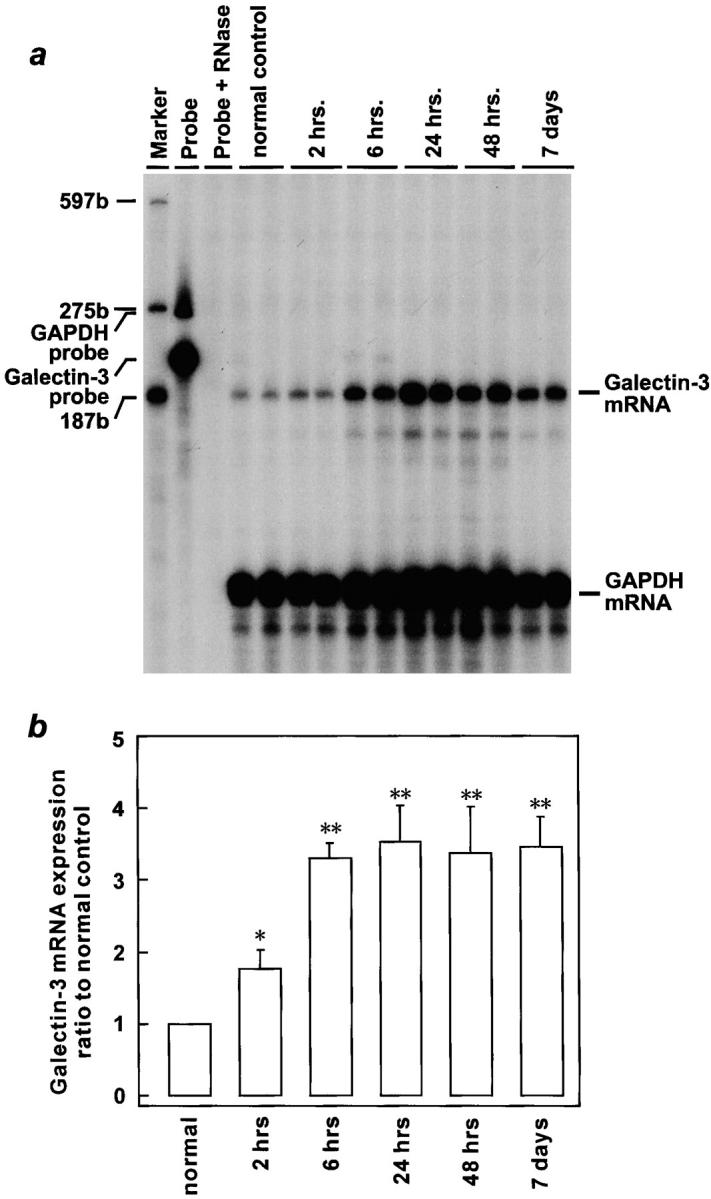

Rapid Induction of Galectin-3 mRNA in Folic Acid Renal Injury

Serum creatinine increased to an average of 3.83 ± 0.23 mg/dl at 48 hours after folic acid injection, compared with mean values of 0.27 ± 0.08 mg/dl in the sham group (P < 0.01), which indicated that animals injected folic acid developed severe ARF. Then, an average of serum creatinine decreased to 0.38 ± 0.08 mg/dl at 7 days after injection. No significant difference was shown in galectin-3/GAPDH mRNA ratio between normal and sham rat kidneys at both 24 and 48 hours after sham injection. However, as shown in Figure 3 ▶ , galectin-3 mRNA markedly increased in injured kidneys as compared with that in normal control. Time-course study revealed that galectin-3 mRNA developed as early as 2 hours after folic acid injection, which was compatible with that in ischemia/reperfusion ARF rats. Then, it was elevated progressively up to 24 hours after injury by 3.5-fold as compared with that in normal rats (P < 0.01). Thereafter, up-regulation of galectin-3 mRNA lasted until at least 7 days after injection.

Figure 3.

Induction of galectin-3 mRNA expression in the rat kidney after folic acid injury. The representative autoradiogram (exposed for 12 days) was shown (a). Sizes of marker RNAs were indicated to the left. The amount of galectin-3 mRNA was normalized for GAPDH mRNA, and the results were expressed as ratio to normal control rats (b). Data are presented as means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared with control; **P < 0.01 compared with control.

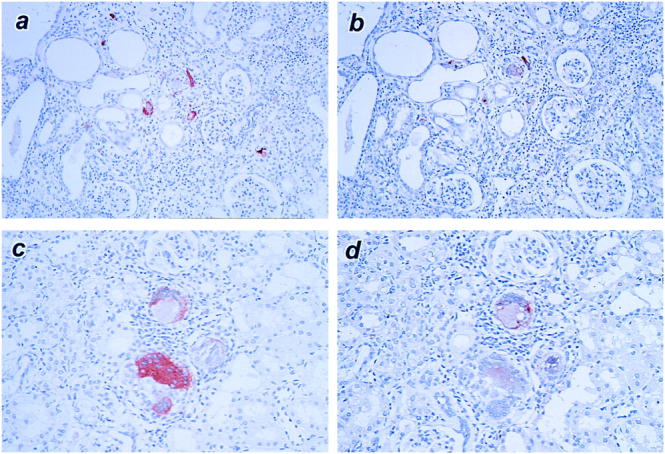

Localization of Galectin-3 in Kidney

Negative controls for immunohistochemistry showed no staining for galectin-3 (Figure 4a) ▶ . In the normal and sham-operated kidneys, little galectin-3 was detected, with a fairly weak staining in some distal tubules (Figure 4b) ▶ . At 20 minutes of reperfusion following ischemia, galectin-3 expression didn’t show any changes (n = 2, data not shown). However, at 2 hours after ischemia/reperfusion injury, proximal tubules located in the renal cortex (S1 and S2) exhibited galectin-3-positive reactions, particularly along basolateral sides (Figure 4c) ▶ . At the period, some proximal straight tubules (S3) also showed galectin-3 expression, but much less than S1 or S2. At 6 hours after injury, galectin-3 expression extended to distal tubules, ascending limbs of Henle’s loop, and collecting ducts in addition to proximal convoluted and straight tubules (Figure 4d) ▶ . In the proximal tubules, its expression was found to spread out in cytoplasm with marked intensities at this period (Figure 4e) ▶ . At 24 and 48 hours after reperfusion, galectin-3 immunoreactivity was found to be positive in both proximal convoluted and straight tubular cells fell into lumens (Figure 4f) ▶ . At 7 and 14 days after injury, galectin-3 immunoreactivity in tubules was almost normalized. However, some animals in ARF group, which showed relatively large amount of galectin-3 mRNA, also exhibited its immunoreactivity in some glomeruli and interstitium at 14 and 28 days after reperfusion (Figure 4, g and h) ▶ . At 28 days, the cells in interstitium that showed positive immunoreactivity for galectin-3 also showed ED-1-positive immunoreactivity, as demonstrated by examination using serial sections. Therefore, these cells appeared to be macrophages (Figure 5) ▶ .

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemical localization of galectin-3 in kidney sections after ischemia/reperfusion injury. All sections counterstained with hematoxylin. Negative controls showed no immunoreactivity for galectin-3 (a). Normal control rat sections, showing very weak galectin-3 immunoreactivity confined to some distal tubules (b). Galectin-3 induced in the proximal convoluted tubules particularly along basal sides after 2 hours (c). Galectin-3 expression expanded to proximal straight tubules, distal tubules, ascending limbs of Henle’s loop, and collecting ducts at 6 hours after injury (d). In the proximal convoluted tubules, it spread out cytoplasm (e). At 24 hours and 48 hours after reperfusion, intense staining was observed in proximal tubular epithelial cells detached from TBM. Micrograph showing section of 24 hours after injury (f). Little staining for galectin-3 was observed in tubules; however, its expression was found in some glomeruli and interstitium at 14 days after injury (g and h). Original magnifications, ×64 (a), ×240 (b, e, g), ×360 (c and f), and ×120 (d and h).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry showing expression of galectin-3 and macrophage antigen ED-1 in kidney sections at 28 days after ischemia/reperfusion injury. Micrographs of a and b, and those of c and d are serial sections, respectively (a and c, galectin-3; b and d, ED-1). Note that dilated tubules and a number of galectin-3-positive/ED-1-positive interstitial macrophages are found even at 28 days after injury (a and b). Some macrophages look like giant cells (c and d). Original magnifications, ×120 (a and b) and ×150 (c and d).

Discussion

In the present study, by RPA and immunohistochemistry we demonstrated that galectin-3 expression was up-regulated in ARF. In both normal and sham-operated animal kidneys, galectin-3 mRNA levels were low. Corresponding to these findings, normal and sham-operated rats expressed little galectin-3 and the distribution was confined to some distal tubules, which was compatible with previous reports. 39,40 Galectin-3 expression during ischemia was not examined. However, in view of declines of ATP that are known to occur during ischemia, it is unlikely that cells would synthesize proteins at this period. Indeed, at 20 minutes of reperfusion following ischemia showed as little galectin-3 as normal control. From 2 hours after ischemia/reperfusion injury, galectin-3 mRNA expression began to increase and elevated up to 48 hours. This up-regulation was in parallel with galectin-3 expression in tubules, particularly proximal convoluted tubule epithelial cells. Thus, it was suggested that galectin-3 was synthesized in these cells in early phase of ischemia/reperfusion ARF, although definitive proof would require in situ hybridization studies.

To see whether the up-regulation of galectin-3 mRNA is specific to ischemia/reperfusion injury, we also examined the change of its expression in folic acid-induced ARF. Folic acid is well known to be a nephrotoxic insult. It causes tubular (particularly collecting duct) obstruction and cell damage and has a direct effect on biochemical systems in the renal tissue. 41 Rats receiving folic acid in high doses show great injury to all tubular cell types, especially proximal tubules and collecting ducts. 34,42,43 The recovery phase from folic acid-induced ARF is specific, since DNA synthesis and protein content is markedly increased, resulting in great rise in kidney weight. 44-46 In the present study, morphological findings were compatible with previous reports (data not shown). 34,42,43 Also in this model, galectin-3 mRNA increased after injury. We do not know what signal induces galectin-3 expression in the acute phase of ARF. However, since two models of ARF both showed the galectin-3 mRNA up-regulations as early as 2 hours after injury, it was suggested that these changes were caused not by uremia but by acute cell injury per se, and that the early up-regulations were not specific to causes of injuries, but would be common responses in ARF. Nevertheless, 48 hours of reperfusion after ischemia revealed higher galectin-3 mRNA expression than 48 hours after folic acid treatment, whereas serum creatinine levels were similar. The different intensity of its induction might be ascribed in part to distribution of damaged tubules. Although proximal tubules are mainly impaired by ischemia/reperfusion injury, collecting ducts are major damaged region in folic acid-induced ARF. 34,42,43 Some kinds of growth factor genes and proto-oncogenes are also reported to increase and are suggested to have a role in acute renal injury. 32,33 Studies of the interactions between galectin-3 and those substances would be required. For instance, it would be interesting to know about a relation to another multifunctional protein, clusterin, which is suggested to play an important role in acute renal injury. It is induced in sloughed necrotic tubular epithelial cells as well as normal appearing tubules, in the same way as galectin-3 expression in our present study. 47,48

Two hours after ischemia/reperfusion injury, galectin-3 developed in basolateral sides of the proximal tubules, and then diffusely expanded to cytoplasm except nucleus. After 24 and 48 hours, necrotic cells that were detached from tubular basement membrane (TBM) and fell into lumens strongly expressed galectin-3. Laminin, which is known to be one of the counter-receptors of galectin-3, is a major basement membrane glycoprotein and seems to be altered in post-ischemic ARF. 49 Galectin-3 binds to polylactosamine chains present in laminin and acts as a bridge, linking the cells to the extracellular matrix or to other cells. 22,50,51 Considering the change of its localization in the proximal tubules, galectin-3 might play an important role in interaction between proximal tubular epithelial cells and extracellular matrix protein, particularly laminin of TBM, which may protect these cells against detachment from TBM in acute tubular injury. On the other hand, galectin-3 has been suggested to bind to specific integrins, thereby preventing their interaction with the extracellular matrix proteins. In previous investigations, adding exogenous galectin-3 to several kinds of the cells plated on laminin-coated wells was shown to reduce the cell-matrix adhesion. 23,25 From this point of view, outbursts of galectin-3 expression in proximal tubules in this ARF model could result in accelerating detachment from TBM. If so, anti-galectin-3 antibody exogenously administered might reduce detachment of tubular epithelial cells from TBM, thereby ameliorating acute renal injury.

Recently, apoptosis has been thought to participate in acute renal injury. 29,30,52,53 Two peaks of apoptosis have been described in post-ischemic ARF. The first peak coincides with a burst of proliferative activity, which is observed maximally 2 to 3 days after reperfusion. The second one is noticed at 7 to 8 days post-injury when the hyperplastic tubules are returned to their original cellularity. 52 Our study revealed that galectin-3 mRNA was up-regulated at these periods. Galectin-3 is suggested to be a powerful counteracting agent to apoptosis, since it contains the asparagine-tryptophan-glycine-arginine amino acid sequence highly conserved in the BH1 domain of the bcl-2, a well-characterized suppressor of apoptosis. 26,27 Therefore, there is a possibility that galectin-3 participated in apoptosis in acute renal injury. Furthermore, since galectin-3 modulates cell growth and proliferation, it might be also involved in regeneration after injury. 21 In fact, folic acid-induced ARF rats, characteristic of marked tubular cell regeneration, showed increased levels of galectin-3 mRNA. The up-regulation lasted until at least 7 days after injection, when serum creatinine was normalized to 0.38 ± 0.08 mg/dl with marked tubular cell regeneration.

At 7 and 14 days after reperfusion injury, the galectin-3 expression in the tubules was reduced. However, some animals in ARF group, which showed relatively large amount of galectin-3 mRNA, also exhibited galectin-3 immunoreactivity in some glomeruli or interstitium. Although it has been recently reported that galectin-3 is expressed in mesangial cells of anti-Thy1.1 glomerulonephritis, in the present study its expression was localized along glomerular capillary walls, not in mesangium. 40 Since galectin-3 has also been known to be expressed in fibroblasts, the galectin-3 expression in the interstitium may be required for cell-cell or cell-extracellular matrix interactions. 54 At 28 days after injury, a few animals in the ARF group, which showed relatively large amount of galectin-3 mRNA, were also found to have galectin-3-positive cells in the interstitium. Our study, using serial sections, demonstrated that these galectin-3-positive cells were ED-1-positive activated macrophages. 55 Because these macrophages are clearly known to be involved in inflammatory response and fibrosis, galectin-3 expressions in the macrophages appear to participate in later stage of regeneration, which has been reported to require more than 1 month. 56

In conclusion, we found that galectin-3 mRNA level was elevated in ischemia/reperfusion renal failure and that there was a highly significant correlation between its expression and renal injury. In addition, up-regulation of galectin-3 mRNA was also shown in folic acid-induced ARF. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated that galectin-3 expression was localized in proximal tubules and extended to more distal side as time goes by after reperfusion. We speculate that galectin-3 plays an important role in pathophysiology of acute renal injury. However, since galectin-3 is known to be multifunctional, further study will be required.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. R. Colin Hughes for providing galectin-3 antiserum and Mr. Kazuya Funato for preparation of figures.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Shuzo Kobayashi, M.D., Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, 1202–1 Yamazaki, Kamakura 247-8533, Japan. E-mail: shuzo@japan.co.jp.

References

- 1.Barondes SH, Cooper DN, Gitt MA, Leffler H: Galectins: structure and function of a large family of animal lectins. J Biol Chem 1994, 269:20807-20810 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barondes SH, Castronovo V, Cooper DN, Cummings RD, Drickamer K, Feizi T, Gitt MA, Hirabayashi J, Hughes C, Kasai K, Leffler H, Liu F, Lotan R, Mercurio AM, Monsigny M, Pillai S, Poirer F, Raz A, Rigby PW, Rini JM, Wang JL: Galectins: a family of animal beta-galactoside-binding lectins (letter). Cell 1994, 76:597-598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perillo NL, Marcus ME, Baum LG: Galectins: versatile modulators of cell adhesion, cell proliferation, and cell death. J Mol Med 1998, 76:402-412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato S, Burdett I, Hughes RC: Secretion of the baby hamster kidney 30-kDa galactose-binding lectin from polarized and nonpolarized cells: a pathway independent of the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi complex. Exp Cell Res 1993, 207:8-18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleves AE, Cooper DN, Barondes SH, Kelly RB: A new pathway for protein export in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 1996, 133:1017-1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gitt MA, Barondes SH: Evidence that a human soluble beta-galactoside-binding lectin is encoded by a family of genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1986, 83:7603-7607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paroutaud P, Levi G, Teichberg VI, Strosberg AD: Extensive amino acid sequence homologies between animal lectins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987, 84:6345-6348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caron M, Bladier D, Joubert R: Soluble galactoside-binding vertebrate lectins: a protein family with common properties. Int J Biochem 1990, 22:1379-1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Springer TA: Monoclonal antibody analysis of complex biological systems. Combination of cell hybridization and immunoadsorbents in a novel cascade procedure and its application to the macrophage cell surface. J Biol Chem 1981, 256:3833-3839 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho MK, Springer TA: Mac-2, a novel 32,000 Mr mouse macrophage subpopulation-specific antigen defined by monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol 1982, 128:1221-1228 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu FT: S-type mammalian lectins in allergic inflammation. Immunol Today 1993, 14:486-490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeng KC, Frigeri LG, Liu FT: An endogenous lectin, galectin-3 (epsilon BP/Mac-2), potentiates IL-1 production by human monocytes. Immunol Lett 1994, 42:113-116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bao Q, Hughes RC: Galectin-3 expression and effects on cyst enlargement and tubulogenesis in kidney epithelial MDCK cells cultured in three-dimensional matrices in vitro. J Cell Sci 1995, 108:2791-2800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winyard PJ, Bao Q, Hughes RC, Woolf AS: Epithelial galectin-3 during human nephrogenesis and childhood cystic diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol 1997, 8:1647-1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castronovo V, Van Den Brule FA, Jackers P, Clausse N, Liu FT, Gillet C, Sobel ME: Decreased expression of galectin-3 is associated with progression of human breast cancer. J Pathol 1996, 179:43-48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lotz MM, Andrews CW, Jr, Korzelius CA, Lee EC, Steele GD, Jr, Clarke A, Mercurio AM: Decreased expression of Mac-2 (carbohydrate binding protein 35) and loss of its nuclear localization are associated with the neoplastic progression of colon carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993, 90:3466-3470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pienta KJ, Naik H, Akhtar A, Yamazaki K, Replogle TS, Lehr J, Donat TL, Tait L, Hogan V, Raz A: Inhibition of spontaneous metastasis in a rat prostate cancer model by oral administration of modified citrus pectin. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995, 87:348-353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu XC, el-Naggar AK, Lotan R: Differential expression of galectin-1 and galectin-3 in thyroid tumors: potential diagnostic implications. Am J Pathol 1995, 147:815–822 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Wang L, Inohara H, Pienta KJ, Raz A: Galectin-3 is a nuclear matrix protein which binds RNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1995, 217:292-303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dagher SF, Wang JL, Patterson RJ: Identification of galectin-3 as a factor in pre-mRNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:1213-1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inohara H, Akahani S, Raz A: Galectin-3 stimulates cell proliferation. Exp Cell Res 1998, 245:294-302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woo HJ, Shaw LM, Messier JM, Mercurio AM: The major non-integrin laminin binding protein of macrophages is identical to carbohydrate binding protein 35 (Mac-2). J Biol Chem 1990, 265:7097-7099 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato S, Hughes RC: Binding specificity of a baby hamster kidney lectin for H type I and II chains, polylactosamine glycans, and appropriately glycosylated forms of laminin and fibronectin. J Biol Chem 1992, 267:6983-6990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohannesian DW, Lotan D, Thomas P, Jessup JM, Fukuda M, Gabius HJ, Lotan R: Carcinoembryonic antigen and other glycoconjugates act as ligands for galectin-3 in human colon carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 1995, 55:2191-2199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ochieng J, Leite-Browning ML, Warfield P: Regulation of cellular adhesion to extracellular matrix proteins by galectin-3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998, 246:788-791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang RY, Hsu DK, Liu FT: Expression of galectin-3 modulates T-cell growth and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:6737-6742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akahani S, Nangia-Makker P, Inohara H, Kim HR, Raz A: Galectin-3: a novel antiapoptotic molecule with a functional BH1 (NWGR) domain of Bcl-2 family. Cancer Res 1997, 57:5272-5276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kribben A, Edelstein CL, Schrier RW: Pathophysiology of acute renal failure. J Nephrol 1999, 12(suppl 2):S142-S151 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schumer M, Colombel MC, Sawczuk IS, Gobe G, Connor J, O’Toole KM, Olsson CA, Wise GJ, Buttyan R: Morphologic, biochemical, and molecular evidence of apoptosis during the reperfusion phase after brief periods of renal ischemia. Am J Pathol 1992, 140:831-838 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burns AT, Davies DR, McLaren AJ, Cerundolo L, Morris PJ, Fuggle SV: Apoptosis in ischemia/reperfusion injury of human renal allografts. Transplantation 1998, 66:872-876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lieberthal W: Biology of ischemic and toxic renal tubular cell injury: role of nitric oxide and the inflammatory response. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 1998, 7:289-295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammerman MR: Growth factors and apoptosis in acute renal injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 1998, 7:419-424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Safirstein RL: Lessons learned from ischemic and cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in animals. Ren Fail 1999, 21:359-364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klingler EL, Evan AP, Anderson RE: Folic acid-induced renal injury and repair. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1980, 104:87-93 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albrandt K, Orida NK, Liu FT: An IgE-binding protein with a distinctive repetitive sequence and homology with an IgG receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1987, 84:6859-6863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N: Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem 1987, 162:156-159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehul B, Bawumia S, Hughes RC: Cross-linking of galectin 3, a galactose-binding protein of mammalian cells, by tissue-type transglutaminase. FEBS Lett 1995, 360:160-164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kasper M, Hughes RC: Immunocytochemical evidence for a modulation of galectin 3 (Mac-2), a carbohydrate binding protein, in pulmonary fibrosis. J Pathol 1996, 179:309-316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foddy L, Stamatoglou SC, Hughes RC: An endogenous carbohydrate-binding protein of baby hamster kidney (BHK21 C13) cells: temporal changes in cellular expression in the developing kidney. J Cell Sci 1990, 97:139-148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sasaki S, Bao Q, Hughes RC: Galectin-3 modulates rat mesangial cell proliferation and matrix synthesis during experimental glomerulonephritis induced by anti-Thy1.1 antibodies. J Pathol 1999, 187:481-489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt U, Dubach UC: Acute renal failure in the folate-treated rat: Early metabolic changes in various structures of the nephron. Kidney Int 1976, 10:S39-S45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Byrnes KA, Ghidoni JJ, Suzuki M, Thomas H, Mayfield ED Jr: Response of the rat kidney to folic acid administration. II. Morphologic studies. Lab Invest 1972, 26:191–200 [PubMed]

- 43.Schubert GE: Folic acid-induced acute renal failure in the rat: morphological studies. Kidney Int 1976, 10:S46-S50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor DM, Threlfall G, Buck AT: Stimulation of renal growth in the rat by folic acid. Nature 1966, 212:472-474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Threlfall G, Taylor DM, Buck AT: The effect of folic acid on growth and deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in the rat kidney. Lab Invest 1966, 15:1477-1485 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Threlfall G, Taylor DM, Buck AT: Studies of the changes in growth and DNA synthesis in the rat kidney during experimentally induced renal hypertrophy. Am J Pathol 1967, 50:1-14 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosenberg ME, Paller MS: Differential gene expression in the recovery from ischemic renal injury. Kidney Int 1991, 39:1156-1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nath KA, Dvergsten J, Correa-Rotter R, Hostetter TH, Manivel JC, Rosenberg ME: Induction of clusterin in acute and chronic oxidative renal disease in the rat and its dissociation from cell injury. Lab Invest 1994, 71:209-218 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin JJ, Partin J, Kaskel FJ: Changes in laminin during recovery from postischemic acute renal failure in rats. Exp Nephrol 1996, 4:279-285 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee EC, Woo HJ, Korzelius CA, Steele GD, Jr, Mercurio AM: Carbohydrate-binding protein 35 is the major cell-surface laminin-binding protein in colon carcinoma. Arch Surg 1991, 126:1498-1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuwabara I, Liu FT: Galectin-3 promotes adhesion of human neutrophils to laminin. J Immunol 1996, 156:3939-3944 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimizu A, Yamanaka N: Apoptosis and cell desquamation in repair process of ischemic tubular necrosis. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol 1993, 64:171-180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gobe G, Zhang XJ, Cuttle L, Pat B, Willgoss D, Hancock J, Barnard R, Endre RB: Bcl-2 genes and growth factors in the pathology of ischaemic acute renal failure. Immunol Cell Biol 1999, 77:279-286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cherayil BJ, Weiner SJ, Pillai S: The Mac-2 antigen is a galactose-specific lectin that binds IgE. J Exp Med 1989, 1972, 170:1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Askew D, Burger CJ, Elgert KD: Modulation of alloreactivity by Mac-1+, -2+, and -3+ macrophages from normal and tumor-bearing hosts: flow cytofluorometrically separated macrophages. Immunobiology 1990, 182:1-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bayati A, Nygren K, Kallskog O, Wolgast M: The long-term outcome of postischemic acute renal failure in the rat. Ren Fail 1992, 14:333-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]