Abstract

Acute tubular cell injury is accompanied by plasma membrane phospholipid breakdown. Although cholesterol is a dominant membrane lipid which interdigitates with, and impacts, phospholipid homeostasis, its fate during the induction and recovery phases of acute renal failure (ARF) has remained ill defined. The present study was performed to ascertain whether altered cholesterol expression is a hallmark of evolving tubular damage. Using gas chromatographic analysis, free cholesterol (FC) and esterified cholesterol (CE) were quantified in: 1) isolated mouse proximal tubule segments (PTS) after 30 minutes of hypoxic or oxidant (ferrous ammonium sulfate) injury; 2) cultured proximal tubule (HK-2) cells after 4 or 18 hours of either ATP depletion/Ca2+ ionophore- or ferrous ammonium sulfate-mediated injury; and 3) in renal cortex 18 hours after induction of glycerol-induced myoglobinuric ARF, a time corresponding to the so-called “acquired cytoresistance” state (ie, resistance to further renal damage). Hypoxic and oxidant injury each induced ∼33% decrements in CE (but not FC) levels in PTS, corresponding with lethal cell injury (∼50 to 60% LDH release). When comparable CE declines were induced in normal PTS by exogenous cholesterol esterase treatment, proportionate lethal cell injury resulted. During models of slowly evolving HK-2 cell injury, progressive CE increments occurred: these were first noted at 4 hours, and reached ∼600% by 18 hours. In vivo myoglobinuric ARF produced comparable renal cortical CE (and to a lesser extent FC) increments. Renal CE accumulation strikingly correlated with the severity of ARF (eg, blood urea nitrogen versus CE; r, 0.84). Mevastatin blocked cholesterol accumulation in injured HK-2 cells, indicating de novo synthesis was responsible. Acute tubule injury first lowers, then raises, tubule cholesterol content. Based on previous observations that cholesterol has cytoprotectant properties, the present findings have potential relevance for both the induction and maintenance phases of ARF.

Cholesterol is a critical constituent of plasma membranes. 1 In renal tubular cells, it exists in an approximate 1:5 ratio with total plasma membrane phospholipid content (the sum of phosphatidyl-choline, -ethanolamine, -inositol, -serine, and sphingomyelin). 2 Via its interpositing among these phospholipids, cholesterol modulates both membrane structure and biophysics (eg, permeability, phospholipid polar head group associations, hydrocarbon interactions, lipid packing, membrane fluidity, surface charge density, and so forth). 3-7 By exerting these influences, cholesterol secondarily impacts the function of membrane resident enzymes and transport systems. 1

In recent years, it has been recognized that cholesterol is not uniformly distributed throughout the plasma membrane bilayer. Rather, it exists, in part, within specific microdomains, known as rafts and caveolae. 8-12 These microstructures are localized predominantly within the plasma membrane outer leaflet, and arise from cholesterol’s hydrophobic interactions with sphingomyelin and glycosphingolipids. A number of critical enzymes and signaling systems (eg, eNOS, Ras, Rho, MAP kinase, GPIs, Ca2+ regulatory proteins) are concentrated within these microstructures and presumably modulate their expression. 8-12 In composite, then, the above considerations indicate that cholesterol has potentially protean effects on membrane, and hence cellular, homeostasis.

In previous studies dealing with the pathogenesis of acute renal failure, considerable attention has been paid to plasma membrane phospholipid changes during ischemic and toxic tubular damage. 13-16 Based on these studies, it is accepted that with the onset of acute cell injury, phospholipases (most notably PLA2) are activated, resulting in phospholipid degradation and reciprocal lysophospholipid/free fatty acid increments. These changes have been widely implicated in the evolution of acute membrane injury, and hence, necrotic cell death. Given that cholesterol dramatically impacts phospholipid homeostasis as noted above, it is indeed surprising that the issue of membrane cholesterol expression during acute tubular injury has been almost completely ignored.

Several pieces of information have recently emerged from this laboratory which indicate that cholesterol, may in fact, be a critical determinant, or modulator, of acute tubular cell damage. First, we have observed that when cholesterol levels are decreased in cultured proximal tubular (HK-2) cells (either via synthesis blockade with mevastatin or by chemical extraction with methylcyclodextrin), tubule susceptibility to injury is markedly enhanced. 2 Second, if plasma membrane cholesterol is biochemically modified either by low-dose cholesterol esterase (CEase) or cholesterol oxidase (COase) treatment, HK-2 cells are rendered highly vulnerable to superimposed hypoxic or toxic challenges. 2 Third, if freshly isolated mouse proximal tubular segments are exposed to high doses of CEase or COase, profound ATP depletion is rapidly induced, followed shortly thereafter by necrotic cell death; 17 and fourth, we have observed that by 18 to 24 hours after different forms of in vivo renal injury (ischemia-reperfusion, myohemoglobinuria, or urinary tract obstruction) a consistent 20 to 25% enrichment of renal cortical/proximal tubule cholesterol content results. 2 A correlate of these cholesterol increments is proximal tubular cell resistance to superimposed attack (ie, the state of so-called acquired “cytoresistance”). 2 That the cholesterol increments and cytoresistance are mechanistically linked is indicated by observations that restoring proximal tubule cholesterol levels back to normal values abrogates the cytoresistant state. In sum, then: 1) acute cholesterol decrements sensitize to, or evoke, de novo tubular injury; and 2) cholesterol increments protect tubules from superimposed attack.

These observations raise the following additional questions: First, given that experimental manipulation of plasma membrane cholesterol (with CEase or COase) induces lethal tubular injury, it raises the possibility that cholesterol perturbations are a spontaneous correlate of de novo ischemic and toxic renal damage. If this is so, such changes might mechanistically contribute to evolving cell death. Second, because cholesterol exists in cells as both free and esterified cholesterol, it remains to be seen which of these two cholesterol pools might be impacted by an injury process. Third, although we have previously documented increased total cholesterol content in cytoresistant kidneys, it was not determined whether these increments reflected free cholesterol (FC) or cholesterol esters (CEs). (Of note in this regard is that our previous cholesterol assessments 2 were performed using a commercially available enzymatic assay which measures only total cholesterol content, ie, the sum of FC + EC.) Fourth, given that tissue cholesterol increments can arise from increased uptake, ie, via low density lipoprotein, (LDL) receptors, decreased efflux, or de novo synthesis, 18 it remains to be seen which mechanism(s) are responsible for cholesterol accumulation in the cytoresistant state. The following studies were performed to provide insights into each of these four issues.

Materials and Methods

Isolated Proximal Tubule Segment (PTS) Experiments

PTS Preparation

Male CD-1 mice, weighing 25 to 35 g (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), and maintained under normal vivarium conditions, were used for all experiments. They were anesthetized with pentobarbital (∼2 mg i.p.), the kidneys were immediately removed through a midline abdominal incision, the cortices were recovered by dissection with a razor blade on an iced plate, and isolated PTSs were prepared as previously described. 19,20 In brief, the cortical tissues were minced with a razor blade, digested with collagenase, passed through a stainless steel sieve, and then pelleted by centrifugation (4°C). Viable PTSs were recovered by centrifugation through 32% Percoll (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ). After multiple washings in iced buffer, the PTSs were suspended (∼2 to 4 mg PTSs protein/ml) in experimentation buffer (in mmol/L: NaCl, 100; KCl, 2.1; NaHCO3 25; KH2PO4, 2.4; MgSO4, 1.2; MgCl2, 1.2; CaCl2, 1.2; glucose, 5; alanine, 1; Na lactate, 4; Na butyrate, 10; 36-kd dextran, 0.6%) and gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2; final pH, 7.4. They were re-warmed to 37°C in a heated shaking water bath for 15 minutes. Each PTS preparation was divided into 2 to 4 equal aliquots (1.25 ml of PTS suspension placed into 10-ml Erlenmeyer flasks; 2 to 4 mg tubule protein/ml buffer). They were then ready for use in individual experiments, as described below.

Impact of Hypoxia on PTS-FC and CE Expression

The following experiment was conducted to ascertain whether changes in cholesterol profiles occur during the evolution of acute hypoxic tubular damage. To this end, five sets of PTSs, prepared as described above, were each divided into two aliquots, and treated as follows: 1) control incubation for 30 minutes (95% O2/5% CO2); or 2) 15 minutes of hypoxic incubation (gassed with 95% N2/5% CO2) followed by 15 minutes of re-oxygenation. 20 At the completion of these incubations, the extent of cell injury was assessed by determining percent LDH release (assessed on a 150-μl PTS suspension aliquot). Then, 800 μl of each aliquot was added to 3 ml of chloroform:methanol (1:2), followed by sample vortexing and sonication for 15 minutes. They were subjected to lipid extraction as previously described in detail. 16 The lipid samples were dried under N2 and saved for cholesterol analysis (vide infra). The values for FC and CE were expressed as nmol/μmol recovered phospholipid phosphate, the latter being determined by the method of Van Veldhoven and Mannaerts. 21

Impact of Oxidant Stress on PTS-FC and CE Expression

To further explore the impact of acute cell injury on cholesterol expression, six sets of PTSs were each divided into two aliquots, as follows: 1) control incubation conditions, as noted above; and 2) incubation under conditions of iron-mediated oxidative stress, induced with 25 μmol/L ferrous ammonium sulfate (Fe), complexed to 25 μmol/L of hydroxyquinoline (HQ) to permit intracellular Fe access. 22,23 After 30 minutes of incubations, percent LDH release was determined, the samples underwent lipid extraction, and the recovered lipid was analyzed for FC and CE, as detailed below.

Impact of CEase on Renal Tubule Cholesterol and Cell Injury

As noted in the Introduction, CEase treatment of tubules causes lethal cell injury. 17 However, the quantitative impact of CEase of CE levels, and whether those changes might recapitulate those which are hypothesized to occur during hypoxic and oxidant injury, have not been previously defined. Therefore, four sets of PTSs were prepared and divided into two treatment groups: 1) control incubation; and 2) incubation with 2 U/ml of CEase (C-7149; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). After completing a 30-minute incubation, the percent LDH release was determined, followed by tubule processing for cholesterol/CE analysis.

Cholesterol Expression in Cultured Human Proximal Tubule Cells: Impact of Cell Injury

In each of the above isolated tubule experiments, lethal cell injury was induced within a 15- to 30-minute time frame. To assess the impact of a more gradual onset of cell injury on cholesterol expression, experiments were conducted using cultured human proximal tubule (HK-2) cells. 24 (Note: freshly isolated proximal tubules are not suitable for prolonged experimentation because of spontaneous, progressive loss of cell viability after their isolation.) HK-2 cells were cultured in T75 Costar flasks (Costar, Cambridge, MA) with keratinocyte serum-free medium (K-SFM; Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY) containing 1 mmol/L glutamine, 5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 40 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract, 25 U/ml penicillin, and 25 μg/ml streptomycin (37°C; 5% CO2), as previously described. 24 At near confluence, the cells were trypsinized and transferred to additional T75 flasks. The following experiments were conducted ∼3 to 4 days after passage, at near confluence.

Four Hours of ATP Depletion/Ca2+ Overload Injury

Ten flasks of cells were divided into two equal groups: 1) incubation under continued control conditions, as noted above; and 2) combined ATP depletion/Ca2+ overload-mediated cell injury. 25 The latter was induced by simultaneous inhibition of mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis (with 7.5 μmol/L antimycin A and 20 mmol/L 2-deoxyglucose, respectively) plus concomitant cytosolic Ca2+ overload (induced with 10 μmol/L Ca2+ ionophore A23187). 25 After completing a 4-hour incubation, the flasks were decanted, and the supernatants saved for LDH assay. The flasks were washed three times with 10 ml of iced Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS). The cells in each flask were detached into 3 ml of HBSS using a rubber policeman. They were recovered by centrifugation, resuspended in 800 μl of HBSS, and then 3 ml of chloroform:methanol (1:2) was added. The lipids were extracted as previously described 26 and saved for cholesterol analysis. LDH release was determined using the supernatant LDH and total LDH (determined in control incubated flasks).

Four Hours of Fe-Mediated Oxidative Stress

Eight flasks were prepared and divided into two equal groups: 1) 4 hours of control incubation; and 2) 4 hours of iron-mediated oxidative stress (induced with 10 μmol/L of FeHQ). After completing the above challenges, LDH release was determined and then the cells were harvested for cholesterol analysis, as noted above.

Eighteen Hours of Fe-Mediated Oxidative Stress

The above experiment was repeated exactly as described, with the sole exceptions being: 1) that the 10 μmol/L FeHQ challenge was left in place for 18 hours, rather than 4 hours; and 2) five, rather than four, flasks were used for both the control/experimental groups.

Mevastatin Effects on Cholesterol Levels after Fe-Mediated Oxidant Stress

The following experiment was undertaken to assess the impact of cholesterol synthesis on cholesterol accumulation after tubule injury. Eight flasks of HK-2 cells were incubated with 10 μmol/L of FeHQ as noted above either in the presence of 10 μmol/L of mevastatin (in ethanol; final concentration, 0.1%; M2537; Sigma) or mevastatin vehicle (ethanol) (n = 4 flasks each). After completing an 18-hour incubation, LDH release was determined and the cells were harvested for cholesterol analysis.

Renal Cortical Cholesterol Analysis after Glycerol-Induced Myohemoglobinuria

The following experiment was undertaken to ascertain whether cholesterol elevations during the maintenance phase of acute renal failure (ie, during cytoresistance) reflect increases in FC versus CEs. To this end, nine mice, maintained under normal vivarium conditions with free food and water access, were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane, and then they received intramuscular injections of hypertonic glycerol (10 ml/kg of 50% glycerol, inducing muscle necrosis, hemolysis, and hence, myohemoglobinuria). 27 The glycerol was administered in equally divided doses into the upper hind limbs. After the injections, the mice were allowed to immediately recover from anesthesia, they were returned to their cages, and allowed free food and water access. Eighteen hours later, they were anesthetized with pentobarbital (∼2 mg/kg), a blood sample was obtained from the vena cava for blood urea nitrogen (BUN) analysis, and then both kidneys were resected and iced. Cortical tissue samples from each kidney were dissected on an iced plate using a razor blade. The samples were weighed, added to four parts methanol, homogenized, and then extracted in chloroform:methanol (1:2), as previously described in detail. 2 The samples were dried under N2 and saved for cholesterol assay (see below). Kidneys from nine normal mice, processed simultaneously with the above samples, were used to establish normal renal cortical cholesterol/CE concentrations. The left and right kidney results from each mouse were averaged to provide one cholesterol and one CE value for each animal.

FC and CE Analysis

All steroids used in the following analyses (cholesterol; stigmasterol, which served as an internal standard; as well as palmitate, myristate, and laurate esters of cholesterol), were obtained from Steraloids (Newport, RI). Bis-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. All solvents were of analytical grade or better and were obtained from either Burdick and Jackson (Muskegan, MI) or Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). In preparation for the following analyses, the dried samples obtained from the lipid extraction process were reconstituted in 1 to 2 ml of hexane, followed by sonication and vortexing to complete dissolution.

FC Assay

One hundred μl of each sample were transferred to a glass culture tube and 50 μl of an internal standard solution (stigmasterol, 100 μg/ml in ethyl acetate, EtOAc) was added. The samples were evaporated to dryness under N2 and reconstituted in 100 μl of bis-(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (25% v/v EtOAc; Sigma). The samples were transferred to an injection vial, sealed, and heated for 1.0 hour at 60°C. After derivatization was complete, 1 μl was applied to a Hewlett Packard 5890 Series II gas chromatograph fitted with a flame ionization detector and a 30 m × 0.32 mm DB-5 (0.25 μm) column (J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA). The initial temperature (100°C) was maintained for 3.0 minutes, after which it was increased to 40°C/minute to 290°C, and thereafter by 5°C/minute to 300°C for 5 minutes. The trimethylsilyl ether of cholesterol eluted at 12.5 minutes and that of the internal standard at 13.6 minutes.

Cholesterol Esters

Because the fatty acid esters of cholesterol form a very small fraction of the total cholesterol species, the most reproducible results could be obtained by isolating the esters from FC, hydrolyzing them with base, and then analyzing the resultant cholesterol. This separation was achieved using slight modifications of the methods of Kaluzny et al 28 and Hoving et al. 29 A 400-μl aliquot of the hexane sample was applied to an amino solid-phase extraction column (3 ml/500 mg; Varian Bond Elut, Harbor City, CA) which previously had been washed twice with 2.0 ml of hexane. The solvent resulting from the sample application and subsequent elution with 2 ml of hexane contained the desired CEs and was collected in culture tubes. Internal standard was added and then the sample was evaporated to dryness. Hydrolysis of the esters was achieved using a method based on the procedure of Lillienberg and Svanborg. 30 The sample was dissolved by vortexing in 0.5 ml of EtOH, 0.3 ml of 33% KOH was added, and the hydrolysis completed by heating at 55°C for 45 minutes. The sample was allowed to cool, 1.0 ml of water was added, and the resulting solution was extracted with 4.0 ml of hexane. The layers were separated and the hexane dried under N2. The residue was derivatized and quantified, as noted above.

Validation of FC and CE Assay

The following experiment was undertaken to provide confirmation that manipulations in cholesterol/CE content in biological membranes are, in fact, detected by the above described analyses. Isolated membrane vesicles were prepared from normal renal cortices by a previously described technique. 31 In brief, renal cortices from four mice were collected and the tissues were subjected to lipid extraction. The total amount of recovered phospholipid was determined by the phospholipid phosphate assay. 21 The samples were equally divided into 12 glass tubes (0.7 μmol of phosphate per sample) and then dried under N2. For experimentation, 800 μl of HBSS (with Ca2+/Mg2+) was added to each of the tubes, followed by sonication for 30 minutes. The resulting vesicles were incubated in a shaking water bath for 2 hours under the following conditions (n = 4 for each): 1) no additions; 2) addition of 1 U/ml CEase (C-7149; Sigma); and 3) addition of 2 U/ml of COase (C-9281; Sigma). The cholesterol-esterase and cholesterol-oxidase were used to decrease CE and FC levels, respectively. After completing the 2-hour incubations, the lipids were recovered from the HBSS in 4 ml of methylene chloride. They were dried under N2 and the samples were processed for cholesterol and CE, as noted above.

Calculations and Statistics

All values are presented as means ± 1 SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed by either paired or unpaired Student’s t-test. If more than one comparison was made, the Bonferroni correction was applied. Statistical significance was judged by a P value of <0.05.

Results

Cholesterol Assay Performance

The FC assay was tested for reproducibility by performing repeated assays (n = 3) on 10 biological samples. The obtained coefficient of variation ranged from 1.25 to 4.43% (mean coefficient of variation <3%). Assay linearity was confirmed throughout 30 experiments. The r 2 was always ≥0.998. The calculated intercept was consistently <0.2 times the value obtained for the lowest standard. Additional studies were as follows: 1) recovery of CE and subsequent hydrolysis: the recovery studies were done using 2.1 nmol/L of cholesterol laurate and 3.1 nmol/L of cholesterol palmitate. The samples were applied to separate tubes eluted and hydrolyzed as described above. The average recovery was 3.13 nmol/L (101%) for the cholesterol palmitate and 2.25 nmol/L (104%) for the cholesterol laurate. 2) Confirmation of complete separation of FC from the CEs: separation of cholesterol from esters was confirmed by analysis of the ester fraction (in the column eluant) for FC before hydrolysis. There was no detectable cholesterol in these samples. 3) Reproducibility: reproducibility was confirmed by combining a number of samples and analyzing the resulting pool for CEs five times (individual samples did not have enough CEs for multiple analyses). The coefficient of variation for this experiment was 4.67%.

Isolated Proximal Tubule Experiments

Impact of Hypoxia on Isolated Tubule Cholesterol/CE Expression

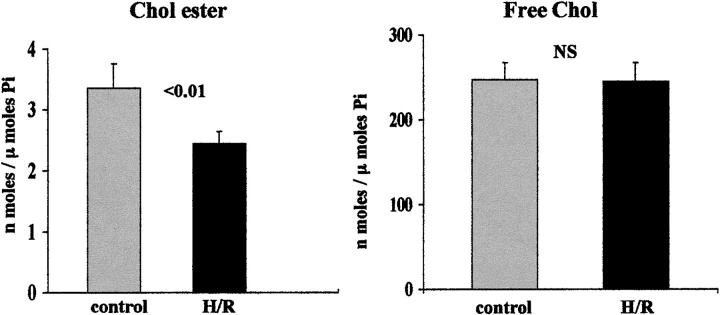

As depicted in Figure 1 ▶ , left, hypoxic/re-oxygenation (H/R) injury induced a 27% decrease in CE levels (P < 0.01). However, there was no corresponding change in FC content (Figure 1 ▶ , right). The H/R protocol induced substantial cell injury, as reflected by percent LDH release (rising from control values of 11 ± 1% to 55 ± 3%; P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Cholesterol (Chol) esters (left) and FC (right) in isolated mouse proximal tubular segments after 30 minutes of control incubation or 30 minutes of hypoxic/re-oxygenation (H/R) injury (15 minutes of hypoxia plus 15 minutes of re-oxygenation). Cell injury induced a significant reduction in CE levels (P < 0.01), without any discernible change in FC content (right).

Impact of Oxidative Stress on Isolated Tubule Cholesterol/CE Expression

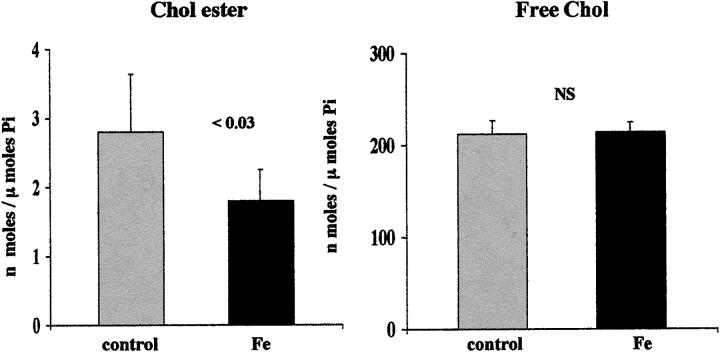

The Fe challenge caused a 38% reduction in CE content (Figure 2 ▶ , left). This was associated with a significant increase in cell death, as reflected by LDH release (45 ± 3%; versus controls, 12 ± 1%; P < 0.001). As with hypoxic injury, FC levels were unaffected by oxidative damage (Figure 2 ▶ , right).

Figure 2.

CE and FC in isolated mouse proximal tubular segments after 30 minutes of control incubation or 30 minutes of iron-mediated oxidative stress (Fe), induced by 25 μmol/L FeHQ. These results mimicked those produced by hypoxia/re-oxygenation, as depicted in Figure 1 ▶ : ie, cell injury induced an ∼38% reduction in CE levels without causing a discernible change in FC content.

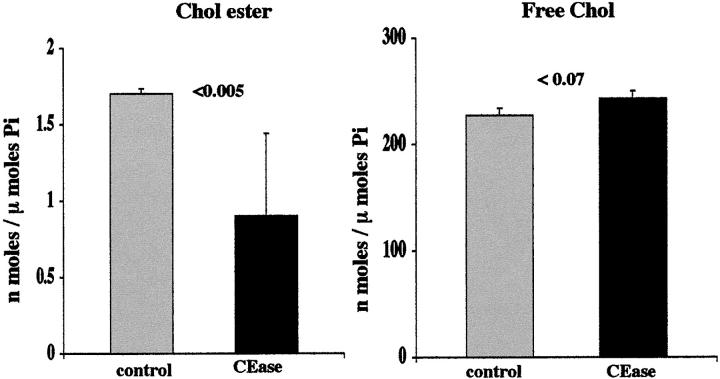

CEase Effects on Tubule Viability and Cholesterol Profiles

As shown in Figure 3 ▶ , incubation with CEase caused an ∼50% reduction in CE levels (left panel). A very slight, (P < 0.07) increase in FC levels was observed. (Note: this was as expected, given that there is normally an ∼100:1 FC/CE ratio; thus, CE hydrolysis, as depicted the left panel, should only minimally affect FC levels.) The CEase treatment induced marked cell death, as assessed by 64 ± 2% LDH release (versus control values of 11 ± 1%; P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Influence of CEase treatment on mouse isolated proximal tubule CE and FC content. After a 30-minute incubation with CEase, an ∼50% reduction in CEs was observed. This corresponded with 64 ± 2% LDH release. Only slight and nonsignificant elevations in FC resulted from CEase treatment (as discussed in Results).

HK-2 Cell Acute Injury Experiments

Four-Hour ATP Depletion/Ca2+ Overload Injury

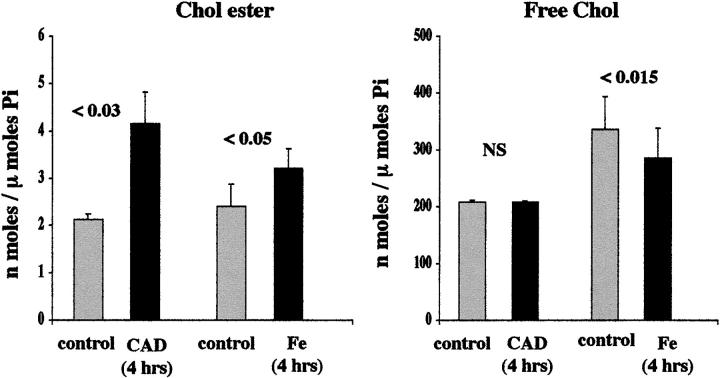

After 4 hours of ATP depletion/Ca2+ ionophore-induced injury (Ca2+ ionophore plus antimcycin plus deoxyglucose), an approximate doubling of CE levels was apparent (Figure 4 ▶ , left). This was expressed in the absence of any change in FC content (Figure 4 ▶ , right). These changes preceded the onset of any lethal cell injury, as assessed by percent LDH release (7 ± 1% LDH release for control and challenged flasks).

Figure 4.

HK-2 cell cholesterol/CE levels after 4 hours of acute cell injury. Left: CE results produced by either the Ca2+ ionophore/antimycin/deoxyglucose (CAD)- or the Fe-mediated challenge are depicted. Right: FC results are presented. Both CAD and Fe caused significant elevations in CE levels. This result appeared more substantial with the CAD versus the Fe challenge (indicating that it is not an ATP-dependent process). The CAD- mediated CE elevations occurred without any change in FC content. Conversely, in the case of Fe, a modest decrement in FC was also observed, consistent with oxidation of FC to an undetected oxidative by-product (eg, cholestenone).

Four-Hour Fe-Mediated Oxidative Stress

Four hours of oxidative stress also produced a significant increase in CE expression, rising ∼40% more than normal values (P < 0.05; Figure 4 ▶ , left). However, unlike the situation with ATP depletion injury, this was associated with a significant, 15%, reduction in FC content (Figure 4 ▶ , right). These two reciprocal changes caused an approximate doubling of the percentage to which CEs contributed to the total cholesterol (FC plus CE) content (1.9 ± 0.3% versus 1.0 ± 0.6% for Fe-treated and normal cells, respectively; P = 0.03). The 4-hour iron challenge caused no increase in percent LDH release (7 ± 1% for control and Fe-treated cells).

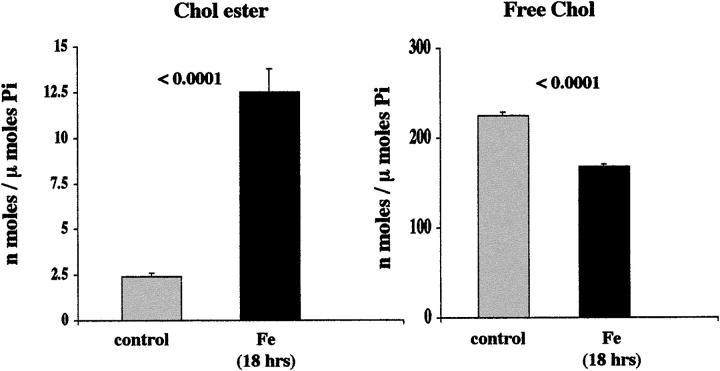

Eighteen-Hour Fe-Mediated Oxidative Stress

As shown in Figure 5 ▶ , left, a sixfold increase in CEs was produced in HK-2 cells by the 18-hour Fe-induced oxidative challenge. This corresponded with an ∼25% decrease in FC content (Figure 5 ▶ , right). The iron challenge was associated with a 65 ± 9% increase in LDH release (controls, <7%).

Figure 5.

HK-2 cell cholesterol/CE results after 18 hours of Fe-mediated oxidative injury. An approximate fivefold increase in CEs resulted after the 18-hour iron challenge (left). Conversely, an ∼20% reduction in FC levels was noted (right). There was a corresponding 65% LDH release after this treatment, suggesting that despite the reductions in absolute FC levels, the amount of FC per residual viable cell was actually increased.

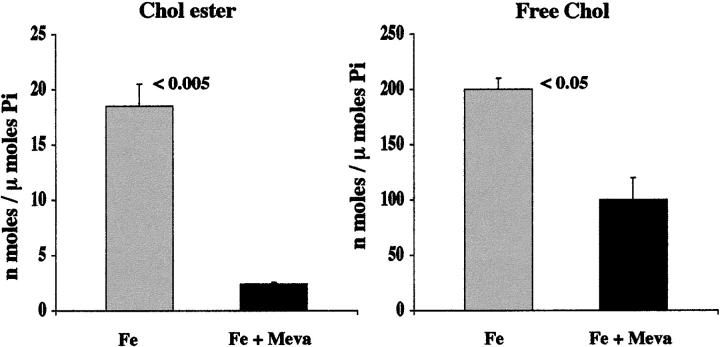

Effect of Mevastatin on Cholesterol Accumulation

The iron treatment, once again, produced striking CE elevations, compared to normal HK-2 values (Figure 6 ▶ , left). Mevastatin treatment almost completely blocked these CE increments, returning them to essentially normal values (from 18.5 ± 2 to 3.4 ± 0.5; P < 0.005 Fe versus Fe/mevastatin treatment; Figure 6 ▶ ). Mevastatin also caused an ∼25% reduction in FC content (203 ± 10 versus 160 ± 20; without versus with mevastatin: P < 0.05). Consistent with previous data, 2 mevastatin increased the extent of cell injury, as assessed by LDH release (70 ± 6% versus 86 ± 2% without versus with mevastatin; P < 0.025).

Figure 6.

Impact of de novo cholesterol synthesis on injury-mediated HK-2 cell cholesterol accumulation. HK-2 cells were incubated with Fe either in the presence of 10 μmol/L of mevastatin or mevastatin vehicle. As depicted, mevastatin (meva) prevented the Fe-mediated increase in CEs/FC, preserving essentially normal concentrations (as determined in above described experiments).

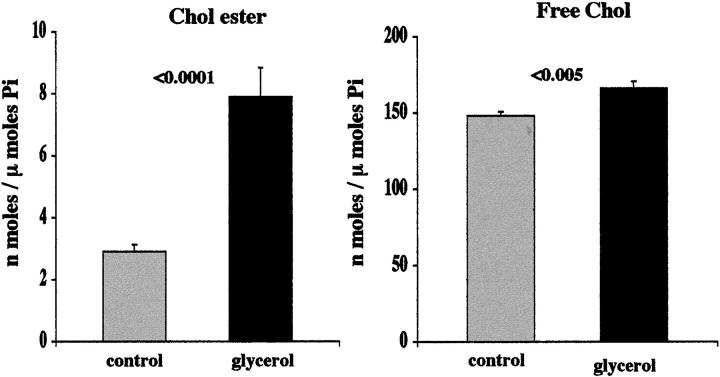

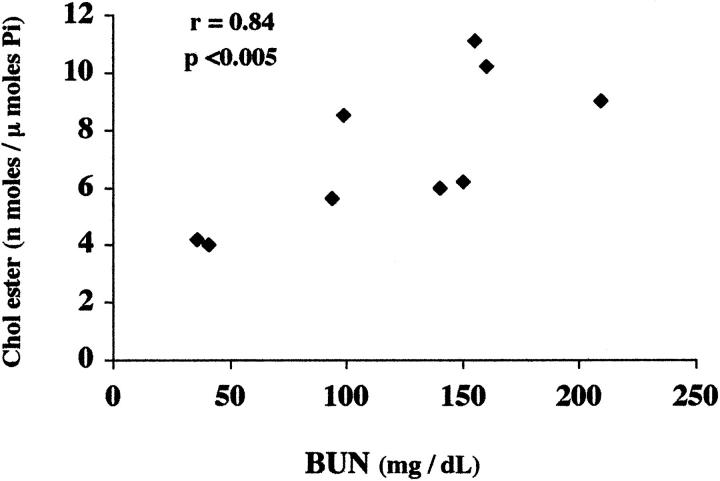

Renal Cortical Cholesterol Concentrations

By 18 hours after glycerol-induced myohemoglobinuria, a significant increase in both FC and CEs were observed (Figure 7) ▶ . Although the increase in FC was modest (11% above normal), the ester pool was proportionally far greater (rising ∼4 times more than control values). There was considerable variation in the degree of CE elevation within the postglycerol group (ranging from 4.0 to 11.1 nmol/μmol phospholipid phosphate). The degree of elevation directly correlated with the severity of renal injury, as assessed by BUN concentrations (r = 0.84; P < 0.005; as depicted in Figure 8 ▶ ). The BUNs ranged from 36 to 09 mg/dL (mean, 111 ± 19 mg/dL, versus controls 34 ± 2; P < 0.001).

Figure 7.

CE and FC levels in renal cortex 18 hours after glycerol-induced myohemoglobinuria. Left: Glycerol-mediated myohemoglobinuria induced striking increases in CE levels. This was associated with a slight (∼11%), but statistically significant (P < 0.005), increase in FC content (right).

Figure 8.

Relationship between the severity of glycerol-mediated renal injury (BUN) and the extent of CE elevations in renal cortex 18 hours after glycerol-induced myohemoglobinuria. When the CE values (which form the composite data presented in Figure 7 ▶ ), are contrasted with the BUN levels at 18 hours after glycerol injection, a highly significant direct relationship (r, 0.84; P < 0.005) is apparent.

Impact of CEase and COase on Vesicle Cholesterol Content

Treating isolated vesicles with COase caused an ∼75% reduction in FC (from 229 ± 14 to 68 ± 10 nmol/μmol phosphate; P < 0.001). When the vesicles were exposed to CEase, a 63% reduction in CEs resulted (from 1.14 ± 0.01 to 0.43 ± 0.01 nmol/μmol phosphate; P < 0.0001). Thus, in both instances, the used assays detected the expected reductions in FC and CE content.

Discussion

Cellular cholesterol homeostasis reflects a balance between a number of complex and interactive processes. These include extracellular cholesterol uptake via the LDL receptor pathway, de novo cholesterol synthesis, intracellular cholesterol trafficking (among organellar, cytosolic, and plasma membrane pools), cellular efflux, and cholesterol esterification/deacylation reactions. 18,32,33 Under normal circumstances, these pathways are exquisitively balanced, resulting in tight regulation of both total cell cholesterol content and stable free versus esterified cholesterol pools. As examples, if cholesterol uptake is increased (eg, via increased LDL cholesterol presentation to the plasma membrane LDL receptor), a reciprocal decrease in cholesterol synthesis occurs (regulated by decreased HMG-CoA reductase activity). Conversely, decreased synthesis (eg, with statin therapy) can be offset by increased cholesterol uptake from circulating LDL pools. In most epithelial cells, the vast majority of cholesterol exists in its nonesterified form. However, under conditions of increased cellular cholesterol production or uptake, acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase produces CEs, generating a CE storage pool. Either acidic (lysosomal) or neutral (cytoplasmic) CE hydrolases can liberate these pools, producing FC which is then available for cellular efflux, facilitated by extracellular cholesterol acceptors (eg, high density lipoproteins). These factors generate a cholesterol/cholesterol esterase cycle. 34 Indeed, cycling between cholesterol and CEs, and cholesterol movement between the lysosome, endoplasmic reticulum, cytosol, plasma membrane, and the extracellular compartment underscore the complexity of cholesterol homeostasis under physiological, and presumably, pathophysiological states.

Normally, cholesterol is asymmetrically distributed within tubular cells, with greater amounts being present in the apical versus the basolateral membrane. 35 As a consequence of acute tubular cell injury, eg, ischemia, this polarity can be perturbed, causing a relative normalization between these two plasma membrane microdomains. 35 However, to our knowledge, there are no studies which have analyzed the quantitative fate of cholesterol during acute cell injury, in general, and whether an alteration in the cholesterol/CE balance is a consequence of tubular injury and repair. The present studies provide new insights into these issues.

The first notable result stemming from the present studies is documentation that acute lethal hypoxic and oxidant tubule injury cause an acute decrease in cell CE content. As shown in Figures 1 and 2 ▶ ▶ , with both forms of injury, an ∼30% reduction in CEs occurred in the absence of any detectable changes in FC levels. Given that both the hypoxic and oxidant insults induced massive cell injury (∼50 to 60% LDH release), it is impossible to know whether the CE losses were pathogenetic contributors to the cell injury, or merely secondary consequences of it. To help with this distinction, isolated proximal tubules were exposed to CEase, which specifically decreases CE pools. As depicted in Figure 3 ▶ , ∼50% reduction in CE content resulted and this was associated with ∼65% LDH release. That comparable relationships between CE reduction and LDH release were observed with CEase, hypoxia, and oxidative injury supports the concept that partial CE depletion during acute cell injury may indeed, have some pathogenetic relevance to evolving tubular damage. Our previous observations that CEase treatment induces profound mitochondrial dysfunction, and that this change occurs before lethal cell injury further supports this concept. 17 The mechanism(s) by which cell injury causes CE loss remains unknown. However, given that free versus esterified cholesterol ratios are primarily determined by a balance between acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase and cholesterol hydrolase activities implies that cell injury dysregulates these enzyme systems. In this regard, it is noteworthy that if CE levels are decreased in cultured cells with acyl-CoA:cholesterol inhibitors (rather than esterase treatment), acute cytotoxicity also results. 36 This underscores the critical role that CEs can play in maintaining cell viability in tubular as well as nontubular cells.

In our previous studies of acquired cytoresistance, a consistent increase in cholesterol accumulation was noted, irrespective of the type of renal insult used to induce this state. 2 The pathogenic relevance of this change was indicated by the fact that lowering cholesterol by any one of a number of methods either predisposed normal cells to injury or abrogated the cytoresistant state. 2 Whether the cholesterol increments were because of free and/or esterified cholesterol accumulation was not previously defined. To clarify this issue, we subjected HK-2 cells to either ATP depletion/Ca2+ ionophore or oxidant injury, and either 4 or 18 hours later (corresponding to sublethal and lethal injury, respectively) free- and esterified-cholesterol levels were determined by gas chromatography. A time dependent increase in CE content was noted, reaching ∼50% and 600% increments at 4 and 18 hours, respectively. Conversely, no absolute increase in FC levels was discerned. However, it should be noted that at the 18-hour time point, the time of maximal CE accumulation, substantial cell death (∼65% LDH release) had supervened. This implies that the amount of FC per residual viable cell was actually increased by at least ∼50%. By the same analogy, the 600% absolute increase in CE accumulation at 18 hours after injury likely represents a gross underestimate of viable cell CE content. That CEs were so dramatically elevated, in both absolute and relative terms, and that CEs are a cholesterol storage form, underscores that tubule cell injury does, in fact, trigger striking positive cholesterol balance.

Given that in vitro data need not necessarily reflect in vivo events, we next sought to determine the cholesterol profiles in cytoresistant renal cortex, as induced by glycerol -mediated myohemoglobinuria. 2 Noteworthy in this regard are our previous observations that total cholesterol rises by ∼20% at 18 hours after this form of renal injury, as previously determined by enzymatic assay. By applying gas chromatographic analysis, once again, an ∼20% increase in total cholesterol was observed, confirming our previously reported quantitative data. 2 Additionally, the current analysis indicates that this total cholesterol increment is comprised of both FC and CEs. The percentage increase in CEs (∼400%) was far greater than that of FC (∼11%), resulting in a striking increase in the CE/FC ratio. This increased ratio undoubtedly reflects excess FC being shunted into the cholesterol storage pool. Although CE may be viewed simply as a storage moiety, this should not be equated with the view that it is biologically inert. Indeed, the converse is suggested by our findings that CE reductions, induced by CEase, induce profound mitochondrial inhibition, followed by necrotic cell death. 17 By analogy, it follows that CE increments, as presently documented for the first time in cytoresistant renal cortex, could serve to protect cells from superimposed attack. That a striking correlation was noted between CE accumulation and the extent of renal injury (BUN versus CE content; r, 0.84), and that increasing degrees of renal injury confer increasing degrees of renal cytoresistance 37,38 further support this view. Whether CEs can directly protect cell membranes from injury (eg, via associated changes in membrane biophysics), or whether more indirect downstream consequences of perturbed cholesterol homeostasis (eg, altered raft or caveoli signaling functions) might be involved remains to be defined.

At least three potential mechanisms exist for cholesterol accumulation after renal cell injury: increased cholesterol uptake via the LDL receptor pathway, decreased cell efflux, or de novo synthesis. Given that injury to HK-2 cells increased cholesterol despite the cells being maintained in a serum-free medium (K-SFM; ie, without LDL), makes enhanced cholesterol uptake highly unlikely. Similarly, decreased cholesterol efflux from cells also seems excluded, given that this process is, in large part, high density lipoprotein-dependent (again, high density lipoprotein being absent from the culture medium). Decreased cholesterol catabolism is also an unlikely explanation for HK-2 cholesterol accumulation, because cholesterol catabolism is believed to be a hepatic-specific process. For each of these reasons, increased cell synthesis seems to be the most likely explanation for the observed cholesterol accumulation. To confirm this hypothesis, HK-2 cells were exposed to injury in the presence and absence of mevastatin therapy. That mevastatin caused an essentially complete block in cholesterol accumulation during iron-mediated injury indicates that increased HMG-CoA reductase activity (ie, de novo cholesterol synthesis) is primarily responsible for the postinjury cholesterol increments. It is noteworthy that increased HMG-CoA reductase activity/cholesterol synthesis should also increase isoprenoid production (eg, farnesyl/geranyl pyrophosphates), and the latter would be expected to drive prenylation reactions, (eg, of Ras and Rho). 39 Thus, the finding of increased cholesterol synthesis/HMG-CoA reductase activity as a correlate of acute tubular injury likely has protean biological implications, extending beyond just increased cholesterol and CE content. The proximate cause(s) for the stimulated cholesterol synthetic pathway (eg, increased HMG-CoA reductase gene transcription versus translation), and the molecular stimuli which give rise to such changes, remain compelling but unresolved issues at this time.

Finally, a few potential caveats inherent to the models used in this study can be noted. First, there is considerable heterogeneity of tubular cells along the nephron, in general, as well as within the proximal tubular epithelium (eg, S1, S2, and S3 segments). Because assessments of renal cortical cholesterol levels do not permit assessment of where the cholesterol increments occur, it could be that differences in cholesterol accumulation among the cell types might exist and impact subsequent injury responses. Indeed, changes in vascular cell cholesterol changes could also potentially occur, potentially impacting hemodynamic responses that occur during the induction or maintenance phases of acute renal failure. Second, although the use of isolated PTSs does permit direct assessments of changes in S1 and S2 proximal tubular cells, by analogy to point one above, these data may not necessarily be relevant to the S3 cells or the kidney as a whole. Furthermore, isolation artifacts may also emerge. Indeed, as with all studies of this kind, these considerations need to be borne in mind during data interpretation. Finally, it should be realized that cell culture results may not be directly applicable to either in vivo or isolated tubule results, given that, in general, cultured tubular cells tend to be glycolytic and relatively undifferentiated. Hence, although each of the above model systems have their potential caveats and may not be always applicable to one another, that three different models have been studied and have yielded generally supportive results, provide a degree of added validity to the results obtained.

In conclusion, based on the present studies conducted in freshly isolated mouse proximal tubules, cultured human proximal tubular cells, and in vivo renal tissues, the following new insights namely cholesterol homeostasis during the initiation and early recovery stages of acute cell injury have emerged: 1) during acute hypoxic or oxidant injury, ∼30% decrements in CEs result. That comparable reductions in CEs induced in normal tubules via CEase induce lethal cell injury suggests that the reductions that develop during hypoxic and oxidant injury may have pathogenic relevance to the evolving tubular damage. 2) After acute tubular injury, a period of heightened cholesterol expression develops: first, this is expressed predominantly as CE accumulation; second, it reaches values as high as 600% of normal; and third, in vivo, the degree of renal cortical CE elevation strikingly correlates with the degree of functional renal damage. 3) Increased cholesterol HMG-CoA reductase mediated cholesterol synthesis is a critical determinant of the postinjury tubular cholesterol increments. Given that an up-regulation of this pathway can impact isoprenoid production and hence, protein prenylation reactions, these findings may have relevance extending well beyond increased cellular cholesterol content. Previous observations indicate that an increase in membrane cholesterol content can protect tubular cells from superimposed attack. Whether additional changes dictated by a stimulated HMG-CoA reductase/mevalonate pathway 39 contribute to the cholesterol-mediated cytoresistance, and whether altered responses to apoptotic, and not just necrotic, cell death might be involved, remain to be defined.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Ms. Katy Anderson and Ms. Ali Johnson.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Richard A. Zager, M.D., Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Ave. N; Room D2 190, PO Box 19024, Seattle, WA 98109-1024. E-mail: dzager@fhcrc.org.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1 DK 38432 and RO1 DK 54200).

References

- 1.Bittman R: Has nature designed the cholesterol side chain for optimal interaction with phospholipids? Subcellular Biochemistry. 1997, :pp 145-171 vol 28, ch 6. Edited by R Bittman. New York, Plenum Press, Cholesterol: Its Functional and Metabolism in Biology and Medicine [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zager RA: Increased proximal tubular cholesterol content: implications for cell injury and “acquired cytoresistance.” Kidney Int 1999, 56:1788–1797 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Presti FT: The role of cholesterol in regulating membrane fluidity. Aloia RC Boggs JM eds. Membrane Fluidity in Biology, Cellular Aspects, 1985, vol 4.:pp 97-146 Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 4.Presti FT, Pace RJ, Chan SI: Cholesterol-phospholipid interaction in membranes. 2. Stoichiometry and molecular packing of cholesterol-rich domains. Biochemistry 1982, 21:3831-3835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bittman R: Sterol exchange between mycoplasma membranes and vesicles. Yeagle PL eds. Biology of Cholesterol. 1988, :pp 173-195 CRC Press, Boca Raton [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeagle PL: Cholesterol and the cell membrane. Yeagle PL eds. Biology of Cholesterol. 1988, :pp 121-145 CRC Press, Boca Raton [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahl J: The role of cholesterol in mycoplasma membranes. Rottem S Kahane I eds. Subcellular Biochemistry, Mycoplasma Cell Membranes, 1993, vol 20:pp 167-188 Plenum Press, New York [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown DA, London E: Function of lipid rafts in biological membranes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 1998, 14:111-136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown DA, London E: Structure and origin of order lipid domains in biological membranes. J Membr Biol 1998, 165:103-114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simons K, Ikonen E: Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature 1997, 387:569-572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson RGW: The caveolae membrane system. Annu Rev Biochem 1998, 67:199-225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown DA, London E: Structure of detergent-resistant membrane domains: does phase separation occur in biological membranes? Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997, 240:1-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinberg JM: The cell biology of ischemic renal injury. Kidney Int 1991, 43:476-500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonventre JV: Mechanisms of ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int 1993, 43:1160-1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edelstein CL, Ling H, Schrier RW: The nature of renal cell injury. Kidney Int 1997, 51:1341-1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zager RA, Sacks BM, Burkhart KM, Williams AC: Plasma membrane phospholipid integrity and orientation during hypoxic and toxic tubular attack. Kidney Int 1999, 56:104-117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zager RA: Plasma membrane cholesterol: a critical determinant of cellular energetics and tubular resistance to attack. Kidney Int 2000, 58:193-205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson WJ, Phillips MC, Rothblat GH: Lipoproteins and cellular cholesterol homeostasis. Subcellular Biochemistry. 1997, :pp 235-276 vol 28, ch 9. Edited by R Bittman. New York, Plenum Press, Cholesterol: Its Functional and Metabolism in Biology and Medicine [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lochhead KM, Kharasch E, Zager RA: Spectrum and subcellular determinants of fluorinated anesthetic-mediated proximal tubular injury. Am J Pathol 1997, 150:2209-2221 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zager RA, Conrad DS, Burkhart K: Phospholipase A2: a potentially important determinant of adenine nucleotide triphosphate levels during hypoxic and reoxygenation tubular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 1996, 7:2327-2339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Veldhoven PP, Mannaerts GP: Inorganic and organic phosphate measurements in the nanomolar range. Anal Biochem 1987, 161:45-48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sogabe K, Roeser NF, Venkatachalam MA, Weinberg JM: Differential cytoprotection by glycine against oxidant damage to proximal tubule cells. Kidney Int 1996, 50:845-865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zager RA: Calcitriol directly sensitizes renal tubular cells to ATP depletion- and iron-mediated attack. Am J Pathol 1999, 154:1899-1909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan MJ, Johnson G, Kirk J, Fuerstenberg SM, Zager RA, Torok-Storb B: HK-2: an immortalized proximal tubule epithelial cell line from normal human. Kidney Int 1994, 45:48-57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwata M, Herrington J, Zager RA: Protein synthesis inhibition induces cytoresistance in cultured human proximal tubular (HK-2) cells. Am J Physiol 1995, 268:F1154-F1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zager RA, Conrad DS, Burkhart K: Ceramide accumulation during oxidant renal tubular injury: mechanisms and potential consequences. J Am Soc Nephrol 1998, 9:1670-1680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nath KA, Balla G, Vercellotti GN, Balla J, Jacob HS, Levitt MD, Rosenberg ME: Induction of heme oxygenase is a rapid and protective response in rhabdomyolysis in the rat. J Clin Invest 1992, 90:267-270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaluzny MA, Duncan LA, Merritt MV, Epps DE: Rapid separation of lipid classes in high yield and purity using bonded phase columns. J Lipid Res 1985, 26:135-140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoving EB, Jansen G, Volmer M, Van Doormaal JJ, Muskiet FA: Profiling of plasma cholesterol ester and triglyceride fatty acids as their methyl esters by capillary gas chromatography, preceded by a rapid aminopropyl-silica column chromatographic separation of lipid classes. J Chromatogr 1998, 434:395-409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lillienberg L, Svanborg A: Determination of plasma cholesterol: comparison of gas-liquid chromatographic, colorimetric, and enzymatic analyses. Clin Chim Acta 1976, 68:223-233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zager RA: Sphingomyelinase and membrane sphingomyelin content: determinants of proximal tubule cell susceptibility to injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000, 11:894-902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown MS, Goldstein JL: Lipoprotein metabolism in the macrophage: implications for cholesterol deposition in atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Biochem 1983, 52:223-261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown MS, Goldstein JL: A receptor mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science 1986, 232:34-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown MS, Ho YK, Goldstein JL: The cholesteryl ester cycle in macrophage foam cells. Continual hydrolysis and re-esterification of cytoplasmic cholesteryl esters. J Biol Chem 1980, 255:9344-9352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molitoris BA, Chan LK, Shapiro JI, Conger JD, Falk SA: Loss of epithelial polarity: a novel hypothesis for reduced proximal tubule Na+ transport following ischemic injury. J Membr Biol 1989, 107:119-127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warner GJ, Stoudt G, Bamberger M, Johnson WJ, Rothblat GH: Cell toxicity induced by inhibition of acyl Coenzyme A: cholesterol acyltransferase and accumulation of unesterified cholesterol. J Biol Chem 1995, 270:5772-5778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zager RA, Baltes LA: Progressive renal insufficiency induces increasing protection against ischemic acute renal failure. J Lab Clin Med 1984, 103:511-523 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zager RA, Baltes LA, Sharma HM, Jurkowitz MS: Responses of the ischemic acute renal failure kidney to additional ischemic events. Kidney Int 1984, 26:689-700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldstein JL, Brown MS: Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature 1990, 343:425-450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]