Abstract

We determined whether hyperplastic mucosa adjacent to colon cancer contributes to neoplastic angiogenesis. Surgical specimens of human colon cancer (40 Dukes’ stage B and 34 Dukes’ stage C) were analyzed by immunohistochemistry for expression of proliferative and angiogenic molecules. The mucosa adjacent to Dukes’ stage C tumors (but not Dukes’ stage B tumors) had a higher Ki-67 labeling index and a higher expression of epidermal growth factor receptor and transforming growth factor-α than distant mucosa. The expression levels of vascular endothelial growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, interleukin-8, and the vascular density in the adjacent mucosa were similar to those in the tumor lesions and significantly higher than those in the distant mucosa. The expression of interferon-β inversely correlated with the level of pro-angiogenic molecules and the vascular density. The injection of metastatic human colon cancer cells and murine colon cancer cells into the cecal wall of mice induced hyperplastic changes in the adjacent mucosa which expressed higher levels of epidermal growth factor receptor, basic fibroblast growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor, and lower levels of interferon-β than did the control mucosa, which directly correlated with the degree of hyperplasia. These data suggest that metastatic human colon cancer cells can induce hyperplasia in the adjacent mucosa, which in turn produces angiogenic molecules that contribute to neoplastic angiogenesis.

The mucosa adjacent to most human colorectal adenocarcinomas is often hyperplastic. 1-3 Several analyses concluded that this transitional mucosa contains more immature and intermediate cells and fewer differentiated cells and more sialomucin secretion than does nonhyperplastic normal mucosa, whose cells predominantly secrete sulfomucins. 4-8 Whether the hyperplastic mucosa adjacent to colon cancer is a precancerous lesion 4,9,10 or a response to the growing cancer 11-14 or to microorganisms, such as Citrobacter freundii in humans 15,16 and Citrobacter rodentium in mice 17 has been debated. Hyperplasia of the ductal epithelium is often found adjacent to mammary adenocarcinoma and pancreatic cancer. Whether this atypical ductal hyperplasia is a precancerous lesion or a reactive change 18-21 is also unclear.

The growth and survival of tumor cells depends on angiogenesis, 22,23 which also increases the likelihood that tumor cells will enter the circulation to produce metastasis. 24-27 Indeed, the number of microvessels within and adjacent to tumor lesions has been shown to be a prognostic factor in human carcinomas of the breast, 28-32 prostate, 33-35 ovaries, 36 stomach, 37 and colon. 38 The onset of angiogenesis is determined by the local balance between pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic molecules. 39-41 Because hyperplastic tissues can express high levels of pro-angiogenic molecules, 42,43 we sought to determine whether the transitional mucosa adjacent to colon carcinomas can contribute to neoplastic angiogenesis. We examined the expression of the pro-angiogenic molecules vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and interleukin-8 (IL-8) and the anti-angiogenic regulator interferon-β (IFN-β) in 74 surgical specimens of human colon cancer and found that the hyperplastic mucosa produces high levels of pro-angiogenic molecules. We also implanted murine and human colon cancer cells into the cecal wall of nude mice and found that the growing tumor lesions induce hyperplasia in the adjacent mucosa that in turn expresses high levels of pro-angiogenic molecules directly correlating with a high degree of vascularity.

Materials and Methods

Surgical Specimens

Seventy-four formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded archival surgical specimens of human primary colon adenocarcinomas that invaded the subserosal layer from four patients treated at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center and 70 patients treated at the J. R. Hiroshima General Hospital of the West Japan Railway Company were chosen at random. In 34 of 74 cases, lymph node metastasis was detected (Dukes’ stage C), and 40 cases had no lymph node metastases (Dukes’ stage B). For each case, the tumor lesion, the adjacent mucosa (within 2 mm of the tumor), and nonpathological control mucosa (at least 10 cm from the edge of the tumor) were studied.

Cultured Cells

The highly metastatic KM12SM cell line was derived from a rare liver metastasis produced by the heterogeneous, low-metastatic KM12C human colon carcinoma cell line growing in the cecal wall of nude mice. 44,45 KM12SM and KM12C human colon cancer cell lines and CT-26 murine colon carcinoma cells syngeneic to BALB/c mice 46 were grown as monolayer cultures in modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, vitamins, sodium pyruvate, l-glutamine, and nonessential amino acids. The adherent monolayer cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 in air. All cultures were free of mycoplasma, reovirus type 3, pneumonia virus of mice, K virus, encephalitis virus, lymphocyte choriomeningitis virus, ectromelia virus, and lactate dehydrogenase virus (assayed by M. A. Bioproducts, Walkersville, MD).

Animal Models

Specific pathogen-free male BALB/c mice and male athymic NCr-nu/nu mice were purchased from the Animal Production Area of the National Cancer Institute–Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center (Frederick, MD). Animals were maintained according to institutional guidelines in facilities approved by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care in accordance with current regulation and standards of the United States Department of Agriculture, Department of Health and Human Services, and National Institutes of Health. The mice were used according to the institutional guidelines when they were 8 to 10 weeks old. Modified Eagle’s medium, Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution, and fetal bovine serum were purchased from M. A. Bioproducts.

To produce cecal tumors, 1 × 10 6 KM12SM or KM12C human colon cancer cells were implanted into the cecal wall of anesthetized nude mice after laparotomy 44,45 and 5 × 10 5 CT-26 murine colon cancer cells were injected into the cecal wall of BALB/c mice. 46 The incision was closed in one layer with wound clips. Tumors were harvested 7 to 28 days after injection. Mice were injected intravenously with 0.2 ml saline containing 250 μg anti-5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) 1 hour before being killed.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Specimens were fixed in buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. For both human and mouse studies, consecutive 4-μm sections were cut from each study block. The sections were immunostained by anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) monoclonal antibody (DAKO Corp., Carpinteria, CA), anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (Becton-Dickinson, Mountain View, CA), anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R) polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), anti-mouse IFN-β polyclonal antibody and anti-human IFN-β polyclonal antibody (Lee Biomolecular Research Laboratories, Inc., San Diego, CA), anti-VEGF/VPF polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-bFGF monoclonal antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, Inc., Lake Placid, NY), anti-IL-8 polyclonal antibody (Biosource, Camarillo, CA), anti-CD31 monoclonal antibody (DAKO Corp.), and anti-Factor VIII polyclonal antibody (DAKO Corp.). Immunohistochemical staining was performed by the immunoperoxidase technique after antigen retrieval: microwave treatment (1000 W) in citrate buffer for 5 minutes for PCNA; 2 N HCl at 37°C for 30 minutes for BrdU; and pepsin (Biomeda Corp., Foster City, CA) at room temperature for 20 minutes for EGF-R, mouse IFN-β, human IFN-β, VEGF/VPF, IL-8, CD31, and Factor VIII. After peroxidase block by 3% H2O2-methanol for 10 minutes, specimens were blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% normal horse serum and 1% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA). The antibodies were used at the following dilutions: 1:50 for PCNA, BrdU, and IL-8; 1:400 for EGF-R, 1:1,000 for mouse IFN-β and human IFN-β; and 1:200 for VEGF/VPF, bFGF, CD31, and Factor VIII. After an overnight incubation at 4°C with primary antibody, specimens were briefly washed with PBS and incubated at room temperature with secondary antibody conjugated with peroxidase: anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG)2a goat antibody (Serotec, Inc., Raleigh, NC) for PCNA; anti-mouse IgG1 antibody (PharMingen, San Diego, CA) for BrdU; anti-mouse IgG antibody (Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA) for bFGF and CD31; and anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Jackson Immuno Research) for EGF-R, mouse IFN-β, human IFN-β, VEGF/VPF, IL-8, and Factor VIII. The specimens were then washed with PBS and color-developed by stable 3,3′-diaminobenzidine solution (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL). After quantitation by colorimetric scanning using a computer, specimens were counterstained with Meyer-hematoxylin (Sigma Chemical Co.).

Oligonucleotide Probes

Based on published reports of the cDNA sequences of EGF-R, 47,48 bFGF, 49,50 IL-8, 51,52 and VEGF, 53,54 specific antisense oligonucleotide DNA probes were designed to complement the mRNA transcripts of these four metastasis-related genes. The specificity of the oligonucleotide sequences was initially determined by a GenEMBL database search using the FastA algorithm, 55 which showed 100% homology with the target gene and minimal homology with nonspecific mammalian gene sequences. The sequences and working dilutions of the probes were as follows: EGF-R, 5′-GGA GCG CTG CCC CGG CCG TCC CGG-3′ (1:800); bFGF, 5′-CGG GAA GGC GCC GCT GCC GCC-3′ (1:200); IL-8, 5′-CTC CAC AAC CCT CTG CAC CC-3′ (1:200); and VEGF, 5′-TGG TGA TGT TGG ACT CCT CAG TGG GC-3′ (1:200). A d(T)20 oligonucleotide was used to verify the integrity of the mRNA in each sample. 56 All DNA probes were synthesized with six biotin molecules (hyperbiotinylated) at the 3′ end via direct coupling using standard phosphoramidine chemistry (Research Genetics). 57,58 The lysophilized probes were reconstituted to a 1 μg/μl stock solution in 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) and 1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. The stock solution was diluted with Probe Diluent (Research Genetics) immediately before use.

In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed using the Microprobe manual staining system (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). 58 Tissue sections (4 μm) of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens were mounted on silane-coated ProbeOn slides (Fisher Scientific). 59 The slides were placed in the Microprobe slide holder, dewaxed, and dehydrated with Autodewaxer and Autoalcohol (Research Genetics), followed by enzymatic digestion with pepsin. 56 Hybridization of the probe was performed for 60 minutes at 45°C, and the samples were then washed three times with 2× standard saline citrate for 2 minutes at 45°C. The samples were incubated in alkaline phosphatase-labeled avidin for 30 minutes at 45°C, briefly rinsed in 50 mmol/L Tris buffer (pH 7.6), rinsed with alkaline phosphatase enhancer (Biomeda Corp.) for 1 minute, and incubated with chromogen substrate FastRed (Research Genetics) for 30 minutes at 45°C. A positive reaction in this assay stained red. To provide a control for endogenous alkaline phosphatase, the samples were treated as described above but in the absence of the biotinylated probe, and chromogen was used in the absence of any oligonucleotide probes. The specificity of the hybridization signal was checked using the following controls: 1) RNase to pretreat tissue section; 2) a biotin-labeled sense probe; and 3) a competition assay with unlabeled antisense probe. A markedly decreased or absent signal was obtained after all these treatments.

TUNEL Method

Apoptotic cells in intestinal tissues were detected by the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end-labeling (TUNEL) method as described previously. 60

Image Analysis to Quantify Intensity of Color Reaction in Immunohistochemistry and in Situ Hybridization

Stained sections were examined in a Zeiss photomicroscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY) equipped with a three-chip charge-coupled device color camera (model DXC-960 MD; Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The images were analyzed using the Optimas image analysis software (version 5.2; Bothell, WA). The slides to be analyzed were prescreened by one of the investigators to determine the range in staining intensity. Images covering the range of staining intensities were captured electronically. For immunostaining, captured images were converted to gray scale, and the threshold value was set to gray scale. All subsequent images were quantified based on this threshold. The integrated optical density (OD) of each selected field was determined based on its equivalence to the mean log inverse gray value multiplied by the area of the field. Because the samples were not counterstained before image analysis, the OD was due solely to immunoreaction. A total of eight hot spots, each consisting of 20 strong-staining cells, 61 were subjected to measurement of intensities: three in the tumor, three in the control mucosa, and three in the mucosa within 2 mm adjacent to the tumor. Staining intensities in each area were measured only on cytoplasm for in situ hybridization and on cytoplasm and/or membrane for immunohistochemistry. Staining of the cells was then quantified to derive an average value of the area. The representative OD value was the mean of three hot spots for the tumor, and the mean of two mucosa at the oral and anal edges for the adjacent mucosa. The measured OD of each in situ hybridization or immunostained specimen was standardized by comparison with the integrated OD of nonpathological control mucosa of the ascending colon in mouse specimens or of nonpathological control mucosa at least 10 cm from the cancer edge in human colon cancer specimens, which were set at 100.

Labeling Index

The labeling index for staining using PCNA, BrdU, and TUNEL methods was determined by the percentage of examined nuclei that were immunoreactive. For each area (tumor, adjacent mucosa, and control mucosa), we examined three hot spots, each containing 100 nuclei and calculated the average index.

Vascular Density

Vascular density was measured on CD31- (for mouse specimens) or factor VIII- (for human specimens) stained specimens in microscopic fields (×200 magnification) at the area with maximum vascular density (hot spot) 61 of the tumor, at the tumor-mucosa junction (for the adjacent mucosa), and at the control distant mucosa.

Statistical Analysis

The mean of the assigned expression levels for EGF-R, VEGF, bFGF, IL-8, human IFN-β, labeling indexes for Ki-67, PCNA, TUNEL, and vascular density were stratified according to the metastatic status of lymph nodes and the location of the measured area. To assess the statistical significance of differences in mean values of the parameters, nonparametric analysis by unpaired Mann-Whitney U test was performed. 62 A P value of = 0.05 was considered significant. Specimen correlation analysis (Stat View, version 4.51; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used to define the significant relationship between the growth factors (TGF-α or IL-15) and a proliferative marker (Ki-67 labeling index) of the adjacent mucosa. 62

Results

Proliferative and Angiogenic Properties of Autochthonous Human Colon Carcinomas and Mucosa

In the first set of studies, we measured proliferative markers (Ki-67 labeling index and expression of EGF-R, TGF-α, and IL-15) and angiogenic properties (expression of bFGF, VEGF, IL-8, and vascular density) in the tumor lesions, adjacent mucosa, and distant mucosa of 74 surgical specimens of human colon carcinomas. We compared the parameters between 34 Dukes’ stage C (lymph node metastasis) and 40 Dukes’ stage B (no evidence of metastasis) tumors. Thirty-two (94%) of the 34 Dukes’ stage C cases and 16 (40%) of the 40 Dukes’ stage B cases had evidence of morphological hyperplasia in the mucosa adjacent to the carcinoma, a change defined as crypt column height ≥1.5-fold that in the control distant mucosa. 1-4 This difference in incidence of mucosal hyperplasia was highly significant (P < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test).

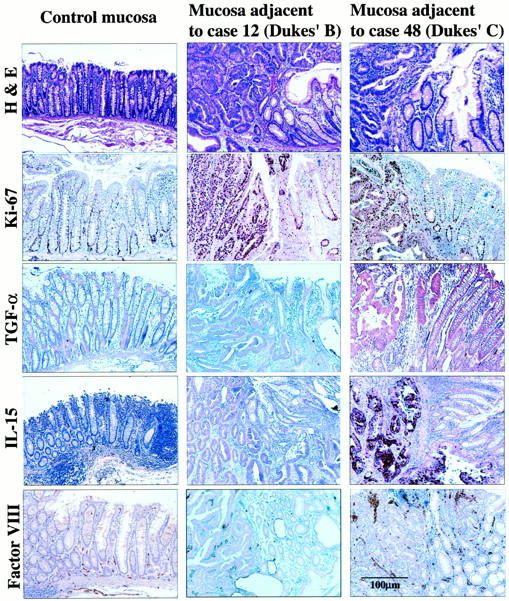

As shown in Table 1 ▶ and Figure 1 ▶ , the mucosa adjacent to Dukes’ C neoplasms expressed higher levels of EGF-R, TGF-α, VEGF, bFGF, and IL-8 than did the distant mucosa. In contrast, the expression of the anti-angiogenic molecule, IFN-β, 63 known to be expressed in differentiated epithelia, 64 was lower in the tumor tissue and the adjacent mucosa than in the distant mucosa. The Ki-67-labeling index (indicating tumor cell proliferation) and the vascular density (indicating angiogenesis) were 3.8- and 10.6-fold higher, respectively, in the mucosa adjacent to the tumors than in the distant control mucosa. No discernible differences in Ki-67-labeling index, vascular density, expression levels of EGF-R, VEGF, bFGF, IL-8, or IFN-β were found between the tumors and the adjacent mucosa. The expression of TGF-α was highest in the tumor tissue, intermediate in the adjacent mucosa, and lowest in the distant mucosa (Table 1) ▶ .

Table 1.

Proliferative and Angiogenic Profiles of Human Colon Cancers and Mucosa

| Factors | Tumor | Adjacent mucosa | Distant mucosa* | P value† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | ||||

| Dukes’ stage C (n = 34) | ||||||

| Ki-67‡ | 38 (18–83) | 19 (6–51) | 5 (0–8) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| EGF-R§ | 233 (122–338) | 200 (138–288) | 100 (98–103) | 0.0049 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| TGF-α§ | 260 (114–425) | 200 (114–357) | 100 (98–103) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| VEGF§ | 227 (136–318) | 209 (145–255) | 100 (98–102) | 0.0034 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| bFGF§ | 181 (119–263) | 163 (113–225) | 100 (98–102) | 0.1145 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| IL-8§ | 138 (106–169) | 131 (106–156) | 100 (97–102) | 0.1677 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Human IFN-β§ | 3 (0–5) | 4 (2–6) | 100 (97–102) | 0.4357 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| IL-15∥ | 67 | 0 | 0 | — | — | — |

| Vascular density¶ | 68 (48–134) | 74 (42–92) | 7 (2–12) | 0.6785 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Dukes’ stage B (n = 40) | ||||||

| Ki-67‡ | 44 (8–85) | 9 (0.3–33) | 5 (0–9) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0224 |

| EGF-R§ | 179 (109–275) | 125 (89–225) | 100 (97–103) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| TGF-α§ | 114 (88–188) | 138 (100–263) | 100 (98–102) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| VEGF§ | 200 (120–318) | 145 (64–218) | 100 (100–102) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| bFGF§ | 163 (113–250) | 125 (88–188) | 100 (97–102) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| IL-8§ | 117 (100–179) | 100 (94–131) | 100 (98–103) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0212 |

| Human IFN-β§ | 7 (3–12) | 63 (42–93) | 100 (96–101) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| IL-15∥ | 8 | 0 | 8 | — | — | — |

| Vascular density¶ | 46 (32–94) | 37 (20–58) | 8 (2–14) | 0.0061 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

*At least 10 cm from the edge of the neoplasm and morphologically nonpathological.

†Significance of differences between 1) the adjacent mucosa and the tumor, 2) the tumor and the distant mucosa, and 3) the adjacent mucosa and distant mucosa (unpaired Mann-Whitney U test).

‡Median (range). Percent Ki-67-positive nuclei in five fields of 30 nuclei each.

§Median (range). Expression intensity was quantitated by a computer program standardized to expression at the control distant mucosa. In control mucosa, three hot spots containing at least 20 cells each were examined, and the average expression was assigned the value of 100.

∥Percent IL-15-positive cells.

¶Median (range). Factor VIII-positive vessels were counted in five microscopic fields (×200).

Figure 1.

Hyperplastic changes in mucosa adjacent to autochthonous human colon carcinomas. Histology: H&E and immunohistochemical staining for Ki-67, TGF-α, IL-15, and Factor VIII are shown for control distant mucosa (descending colon of case 48) and the mucosa adjacent to tumor in case 48. A well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon with lymph node metastasis (Dukes stage C) and case 12 moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid colon without evidence of metastasis (Dukes’ stage B). The Ki-67 labeling indexes for the control distant mucosa, the tumor, and the adjacent mucosa for case 12 were 6, 65, and 12, respectively. For case 48, the values were 12, 45, and 30, respectively. Expression intensity values of TGF-α assessed by immunohistochemistry in the control distant mucosa, the tumor, and the adjacent mucosa of case 12 were 100, 125, and 113, respectively. For case 48, the values were 100, 314, and 200, respectively. Tumor cells in case 48 (Dukes’ C) also expressed IL-15 protein. The numbers of Factor VIII-positive vessels in the control distant mucosa, the tumor, and the adjacent mucosa of case 12 were 2, 48, and 28, respectively. The values in case 48 were 10, 80, and 74, respectively.

The Dukes’ stage B tumors, however, expressed lower levels of the proliferative and angiogenic markers than did Dukes’ stage C tumors (P < 0.001). The Ki-67-labeling index and vascular density in the mucosa adjacent to the Dukes’ stage B tumors were 1.8- and 4.6-fold higher, respectively, than in the control distant mucosa. The expression of IFN-β in the mucosa adjacent to Dukes’ stage B tumors was lower than that in the control distant mucosa. The expression levels of EGF-R, VEGF, bFGF, and IL-8 were also higher in the mucosa adjacent to Dukes’ stage B tumors than in the distant mucosa (P < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U test).

IL-15 is a mitogen for intestinal epithelial cells, especially in inflammatory bowel disease. 65,66 Immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 1) ▶ revealed that colon cancer cells express IL-15 (intratumoral heterogeneity) and that, compared to Dukes’ stage B tumors, Dukes’ stage C tumors expressed a higher level of IL-15. Nonneoplastic epithelial cells were negative for IL-15 expression.

Induction of Hyperplastic Colonic Mucosa and Expression of Angiogenic Molecules

To determine whether the hyperplastic mucosa adjacent to the tumor represents a reactive process or a precancerous lesion, we used an orthotopic murine colon cancer model. Viable nonmetastatic or metastatic colon cancer cells were implanted into the wall of the colon in mice. The highly metastatic human KM12SM cells produced growing tumors in the cecal wall of nude mice (Figure 2) ▶ . By day 7, the implantation of 1 × 10 6 KM12SM cells produced 3.7-mm diameter submucosal tumors. The expression of EGF-R in these lesions and the adjacent mucosa was 2.6-fold higher and 1.8-fold higher, respectively, than in the uninvolved mucosa (Figures 2 and 3) ▶ ▶ . The expression of TGF-α was also up-regulated in the tumors and adjacent mucosa (3.4- and 2.2-fold higher, respectively) than in the distant mucosa. Cell proliferation was determined by PCNA and BrdU labeling at the periphery of the tumors and in the crypt columns of the adjacent mucosa (within 2 mm of the tumor). On day 7 after tumor cell injection, the highest labeling index for PCNA and BrdU was found in small tumor lesions. After day 7, proliferation of tumor cells was reduced, and the high proliferative activity resumed after day 21. In the adjacent mucosa, both PCNA and BrdU labeling indexes were increased from day 7 and reached levels similar to those in the tumor lesions. Mucosal hyperplasia was also morphologically observed from day 7 after tumor cell injection (Figure 3) ▶ .

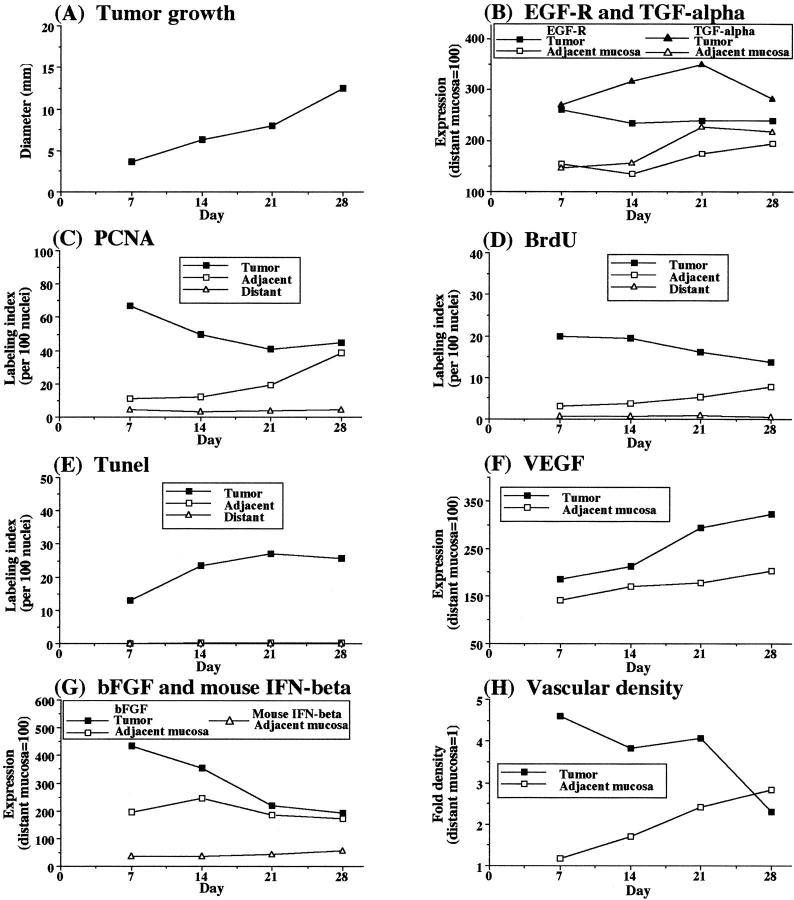

Figure 2.

Growth and expression of angiogenic markers in metastatic human colon carcinoma KM12SM cells implanted into the cecum of nude mice. Nude mice given intracecal injections of 1 × 10 6 viable highly metastatic human colon cancer KM12SM cells were killed at the indicated times. The cecal lesions and mucosa (n = 6) were analyzed by immunohistochemistry for proliferative activities (PCNA and BrdU labeling), apoptosis (TUNEL), and expression of EGF-R, TGF-α, bFGF, mouse IFN-β, and VEGF. Vascular density was determined by immunostaining with CD31. PCNA, BrdU, and TUNEL results are expressed as the percentages calculated from 100 nuclei. Immunohistochemical expression intensity was quantitated by a computer program and standardized to the intensity in control distant mucosa (value set at 100). CD31-positive vasculature was counted in five microscopic fields (original magnification, ×200). The value represents fold increase of that in the control distant mucosa. For all measurements, the SD from the mean did not exceed 10%.

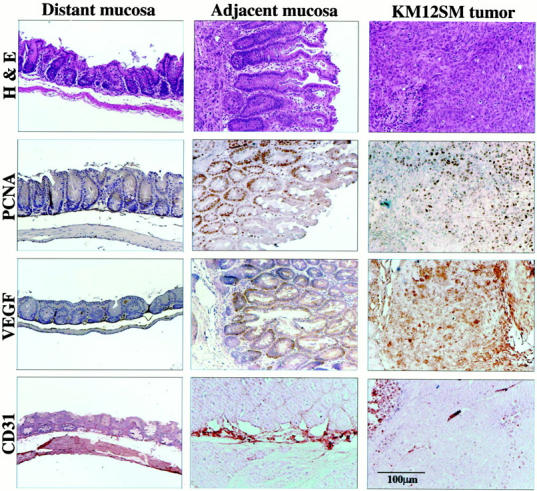

Figure 3.

Histology and immunohistochemistry of colon carcinomas induced in the cecum of nude mice by implantation of highly metastatic KM12SM cells. Mice given intracecal injections of 1 × 10 6 KM12SM cells were killed on day 28. The colon and tumors were prepared for histology and immunohistochemistry. The control distant mucosa is from the descending colon. H&E staining demonstrates that the mucosa adjacent to the tumor contains elongated glands with numerous mitotic figures in PCNA. Labeling indexes in the distant mucosa, adjacent mucosa, and the tumor were 4, 39, and 45, respectively. The values for VEGF intensity were 100, 162, and 271, respectively. Vascular density was assessed by CD31 staining. Marked neovascular formation was found at the junction between the tumor and the adjacent mucosa. The vascular densities in the adjacent mucosa and the tumor were 2.3 and 2.8, respectively, higher than that in the distant mucosa.

We compared the expression levels of VEGF, bFGF, IL-8, and IFN-β in the developing tumors and the adjacent mucosa to those in the control mucosa. The expression of bFGF was increased in the small tumors but not in the large tumors. In both the tumor and the adjacent mucosa, the expression of IFN-β inversely correlated with the expression of bFGF. The expression levels of VEGF and IL-8 were higher in the tumor lesions (regardless of size) and the adjacent mucosa than in the distant mucosa.

The relative expression levels of VEGF, bFGF, IL-8, and IFN-β throughout the experiments were confirmed using an mRNA in situ hybridization technique (data not shown). The chronological changes in the expression levels of the angiogenesis-regulating genes suggested that bFGF is responsible for early stages of angiogenesis, cell division of endothelial cells, and sprouting of capillaries, whereas VEGF and IL-8 play a major role in the maintenance of the neovasculature. 64 Indeed, vascular density in the tumors reached the highest level on day 7, whereas the vasculature at the junction between the tumor and the adjacent mucosa increased to this level 1 to 2 weeks later.

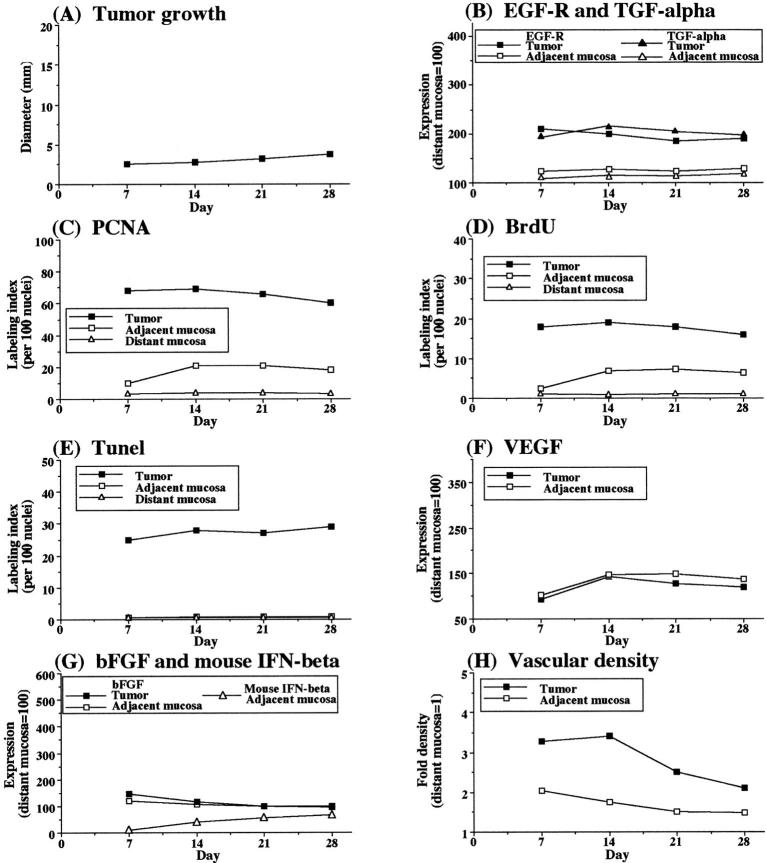

To determine whether metastatic tumors induce a higher degree of mucosal hyperplasia, we compared the cecal tumors produced by highly metastatic KM12SM cells with tumors produced by low-metastatic human KM12C colon cancer cells. Compared to KM12SM cells, KM12C cells injected into the cecal wall of nude mice produced slower-growing tumors (Figures 4 and 5) ▶ ▶ . On day 28, the average diameters of cecal tumors were 3.8 mm and 12.5 mm for the KM12C and KM12SM cells, respectively. The mucosa adjacent to KM12C tumors was less hyperplastic than that adjacent to the KM12SM tumors (Figure 6) ▶ , corresponding to a lower index of PCNA and BrdU labeling (Figure 2) ▶ . The expression levels of EGF-R, TGF-α, VEGF, and bFGF for the KM12C-injected mice, although higher in the tumors than in the distant mucosa, were lower than those found for the metastatic KM12SM tumors. In contrast, the expression of IFN-β was higher in the KM12C (nonmetastatic) than in the KM12SM (metastatic) tumors.

Figure 4.

Growth and expression of angiogenic properties in nonmetastatic human colon carcinoma KM12C cells implanted into the cecum of nude mice. Nude mice given intracecal injections of 1 × 10 6 viable KM12C cells were killed at the indicated times. The cecal tumors and normal mucosa (n = 5) were analyzed by immunohistochemistry for proliferative activities (PCNA and BrdU labeling), apoptosis (TUNEL), and expression of EGF-R, TGF-α, bFGF, mouse IFN-β, and VEGF. Vascular density was determined by immunostaining with CD31. PCNA, BrdU, and TUNEL results are expressed as the percentages calculated from 100 nuclei. Immunohistochemical expression intensity was quantitated by a computer program and standardized to that in control distant mucosa (value set at 100). CD31-positive vasculature was counted in five microscopic fields (original magnification, ×200). The value represents fold increase of that in the control distant mucosa. For all measurements, the SD from the mean did not exceed 10%.

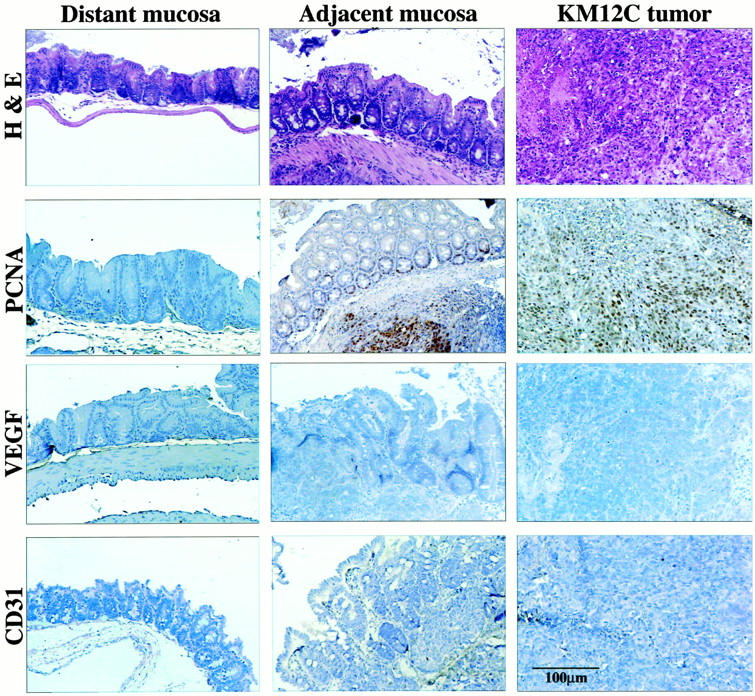

Figure 5.

Histology and immunohistochemistry of colon carcinomas induced in the cecum of nude mice by the implantation of low-metastatic human colon cancer KM12C cells. Mice given intracecal injections of 1 × 10 6 KM12C cells were killed on day 28 (n = 5). The colon and tumors were prepared for histology and immunohistochemistry. The distant mucosa is from the descending colon. H&E staining demonstrates slightly elongated glands with mitotic figures. Labeling indexes (PCNA) in the distant mucosa, adjacent mucosa, and the tumor were 4, 12, and 60, respectively. The indexes for VEGF intensity were 100, 128, and 142, respectively. Vascular density was assessed by CD31 staining. There was no evidence for increased vascular formation at the junction between the tumor and the adjacent mucosa.

Figure 6.

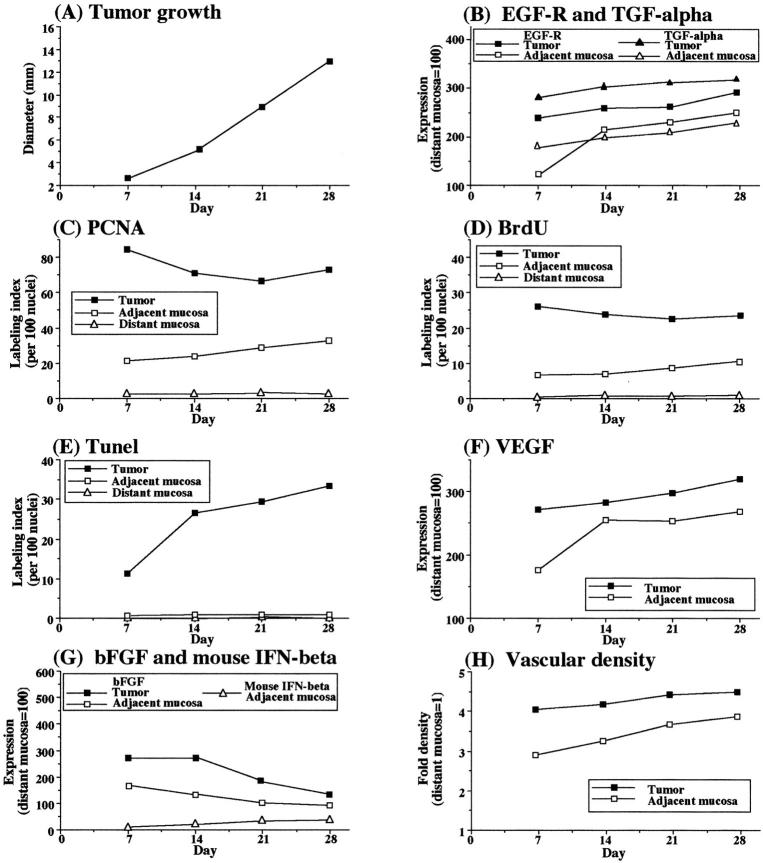

Growth and expression of angiogenic properties in murine CT-26 colon cancer cells implanted into the cecum of BALB/c mice. BALB/c mice given intracecal injections of 2 × 10 5 viable syngeneic CT-26 cells were killed at the indicated times. The cecal tumors and mucosa (n = 5) were analyzed by histology and immunohistochemistry for proliferative activity (PCNA, BrdU), apoptosis (TUNEL), expression of EGF-R, TGF-α, bFGF mouse IFN-β, and VEGF. Vascular density was determined by immunostaining with CD31. PCNA, BrdU, and TUNEL results are given as the percentages calculated from 100 nuclei. Immunohistochemical expression intensity was quantitated by a computer program and standardized to that in control distant mucosa (value set at 100). CD31-positive vasculature was counted in five microscopic fields (original magnification, ×200). The value represents fold increase of that in the control distant mucosa. For all measurements, the SD from the mean did not exceed 10%.

In the final set of experiments, we injected the cecal wall of BALB/c mice with syngeneic CT-26 murine colon cancer cells (Figure 4) ▶ . The results obtained with this syngeneic model were very similar to those obtained with the KM12SM human colon cancer cells in nude mice. EGF-R and TGF-α were highly expressed in cecal tumors and adjacent mucosa. Cell proliferation (as determined using PCNA and BrdU labeling) in tumors was highest on day 7 after injection. In the adjacent mucosa, the highest labeling index followed 7 to 10 days later. This proliferation corresponded to increased vascularity in the adjacent mucosa, with maximal vessel density located at the junction between the tumor and the adjacent mucosa. The expression of IFN-β inversely correlated with cell proliferation, vascular density, and expression of bFGF (Figure 6) ▶ . High expression of VEGF in the tumor was independent of the other parameters.

Discussion

We examined the proliferative index, expression of angiogenic molecules, and vascular density in 74 surgical specimens of human colon carcinomas and in tumors induced in mice by the intracecal implantation of human (nude mice) or murine (syngeneic mice) colon cancer cells with different metastatic potentials. The transitional mucosa adjacent to growing human colon cancers produced high levels of pro-angiogenic molecules and, hence, can contribute to angiogenesis of human colon carcinomas. Neoplastic angiogenesis is known to be regulated by the balance between pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic molecules that are released by the tumor cells 38-41,67-69 and by infiltrating host leukocytes. 70,71 The hyperplasia in the mucosa adjacent to the colon cancers was likely a reaction to the neoplasms rather than a precursor lesion. We base this conclusion on the data showing that mucosal hyperplasia was induced by the intracecal implantation of human or murine colon cancer cells. The extent of the hyperplasia and the production of angiogenic molecules directly correlated with the metastatic potential of the cells, results that agreed with the findings using surgical specimens of human colon carcinomas, ie, Dukes’ stage B versus C neoplasms.

The increased expression of the pro-angiogenic molecules bFGF, VEGF, and IL-8 and the decreased expression of the anti-angiogenic molecule IFN-β in hyperplastic mucosa correlated with an increased vascular density, ie, number and size (diameter) of blood vessels, at the junction between the tumor and the mucosa (Figures 2 and 3) ▶ ▶ . The center of the tumors contained fewer blood vessels than at their periphery, ie, the tumor-mucosa junction, raising the possibility that the increased vascular density was because of pro-angiogenic molecules released by both tumor cells and proliferating mucosal cells.

IFN-β can down-regulate expression and protein production of bFGF 63,72,73 and matrix metalloproteinases. 72-75 This cytokine is expressed in differentiated epithelial cells that line tissues in diverse organs, such as the cornea, skin, gastrointestinal tract, and genitourinary tract, and in the airways. 64 The expression of IFN-β was shown to inversely correlate with the expression of bFGF and hyperplasia of human epidermis adjacent to proliferating hemangiomas. 43 In the murine model used here, the expression of bFGF inversely correlated with the expression of IFN-β in the mucosa adjacent to the developing tumors.

The present data show that colon cancers can induce hyperplasia in normal surrounding tissues. The induction of this mucosal hyperplasia could be mediated by EGF-R and its ligands, which are produced by colon cancer tumor cells 76 that, through an autocrine-paracrine mechanism, can increase tumor cell proliferation and production of pro-angiogenic molecules. 77-79 Indeed, we found high expression levels of EGF-R and TGF-α in metastatic human colon cancers and their adjacent mucosa. Moreover, the analyses of 74 surgical specimens of human colon cancers demonstrated a significant correlation between TGF-α production and Ki-67-labeling index in the tumors and in the adjacent mucosa P = 0.551, P < 0.001, and P = 0.582, and P < 0.0001, respectively (Spearman rank correlation).

IL-15 is a known growth factor for intestinal epithelial cells. The cytokine activates signal transducer and activator of transcription (stat)3 65 and can also activate natural killer cells. 66 IL-15 is known to be produced by monocytes-macrophages. 66 In addition, we found that, like macrophages in the lamina propria, colon cancer cells in advanced Dukes’ stage C lesions produced to IL-15. In fact, the production of IL-15 by tumor cells directly correlated with the Ki-67-labeling index of the adjacent mucosa (P = 0.582, P = 0.00016 by Spearman rank correlation), suggesting that IL-15 produced by cancer cells may also induce hyperplastic changes in the adjacent mucosa.

The present results suggest that immunohistochemical examination of the mucosa adjacent to colon cancer can be used to predict the malignant potential of the neoplasms. Many markers for metastasis of human cancers are located at the invasive edge of the tumors. 80,81 Tissue samples from the invasive edge of human colon cancers are difficult to obtain by colonoscopic examination. However, the adjacent mucosa may be more amenable to such routine screening.

In summary, our results show that human colon carcinomas can induce hyperplasia in the adjacent mucosa. Although the development of this so-called “transitional mucosa” has been recognized for many years, 1-4 our data clearly show that the hyperplastic tissue expresses a high level of pro-angiogenic molecules. This hyperplasia-induced angiogenesis is a perfect example of how tumor cells can usurp host homeostatic mechanisms 82 and explains why the junction between normal tissues and the invasive edge of the tumors is highly vascularized.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kate Ó Súilleabháin for her critical editorial review and Lola López for expert preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Isaiah J. Fidler, D.V.M., Ph.D., Department of Cancer Biology, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd., Box 173, Houston, Texas 77030. E-mail: ifidler@notes.mdacc.tmc.edu.

Supported in part by Cancer Center Support Core Grant CA 16672 and Grant R35-CA 42107 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (to I. J. F.).

References

- 1.Gold J: Metabolic profiles in human solid tumors: a new technique for the utilization of human solid tumors in cancer research and its application to the anaerobic glycolysis of isologous benign and malignant colon tissue. Cancer Res 1966, 2:695-705 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider VA, Machnik G: Mucosal hyperplasia of the rectum: further diagnostic classification needed. Zentralbl allg Pathol Pathol Anat 1986, 131:243-247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greaves P, Filipe MI, Branfoot AC: Transitional mucosa and survival in human colorectal cancer. Cancer 1980, 46:764-770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shamsuddin AK, Weiss L, Phelps PC, Trump BF: Colon epithelium IV: human colon carcinogenesis. Changes in human colon mucosa adjacent to and remote from carcinomas of the colon. J Natl Cancer Inst 1981, 66:413-419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Filipe MI, Branfoot AC: Abnormal patterns of mucus secretion in apparently normal mucosa of large intestine with carcinoma. Cancer 1974, 34:282-290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perrotte P, Matsumoto T, Inoue K, Kuniyasu H, Eve BY, Hicklin DJ, Radinsky R, Dinney CPN: Antiepidermal growth factor receptor antibody C225 inhibits angiogenesis in human transitional cell carcinoma growing orthotopically in nude mice. Clin Cancer Res 1999, 5:257-265 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filipe MI: The value of a study of the mucosubstances in rectal biopsies from patients with carcinoma of the rectum and lower sigmoid in the diagnoses of premalignant mucosa. J Clin Pathol 1972, 25:123-128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Filipe MI, Cooke KB: Changes in composition of mucin in the mucosa adjacent to carcinoma of the colon as compared with the normal: a biochemical investigation. J Clin Pathol 1974, 27:315-318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guan RJ, Fu Y, Holt PR, Pardee AB: Association of K-ras mutations with p16 methylation in human colon cancer. Gastroenterology 1999, 116:1063-1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filipe MI: Mucous secretion in rat colonic mucosa during carcinogenesis induced by dimethylhydrazine: a morphological and histochemical study. Br J Cancer 1975, 32:60-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawady J, Friedman MI, Katzin WE, Mendelsohn G: Role of the transitional mucosa of the colon in differentiating primary adenocarcinoma from carcinomas metastatic to the colon: an immunohistochemical study. Am J Surg Pathol 1991, 15:136-144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franzin G, Grigioni WF, Dina R, Scarpa A, Zamboni G: Mucin secretion and morphological changes of the mucosa in non-neoplastic diseases of the colon. Histopathology 1983, 7:707-718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isaacson P, Attwood PR: Failure to demonstrate specificity of the morphological and histochemical changes in mucosa adjacent to colonic carcinoma (transitional mucosa). J Clin Pathol 1979, 32:214-218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lanza GJ, Altavilla G, Cavazzini L, Negrini R: Colonic mucosa adjacent to adenomas and hyperplastic polyps—a morphological and histochemical study. Histopathology 1985, 9:857-873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barthold SW: The microbiology of transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Lab Anim Sci 1980, 30:167-173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson E, Barthold SW: The ultrastructure of transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Am J Pathol 1979, 97:291-313 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins LM, Frankel G, Connerton I, Goncalves NS, Dougan G, MacDonald TT: Role of bacterial intimin in colonic hyperplasia and inflammation. Science 1999, 285:588-591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mommers EC, van Diest PJ, Leonhart AM, Meijer CJ, Baak JP: Expression of proliferation and apoptosis-related proteins in usual ductal hyperplasia of the breast. Hum Pathol 1998, 29:1539-1545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aaman TB, Stalsberg H, Thomas DB: Extratumoral breast tissue in breast cancer patients: a multinational study of variations with age and country of residence in low- and high-risk countries. WHO Collaborative Study of Neoplasia and Steroid Contraceptives. Int J Cancer 1997, 71:333-339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klöppel G, Bommer G, Rückert K, Seifert G: Intraductal proliferation in the pancreas and its relationship to human and experimental carcinogenesis. Virchow Arch A Pathol Anat 1980, 387:221-233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cubilla AL, Fitzgerald PJ: Morphological lesions associated with human primary invasive nonendocrine pancreas cancer. Cancer Res 1976, 36:2690-2698 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gimbrone M, Cotran R, Folkman J: Tumor growth and neovascularization: an experimental model using rabbit cornea. J Natl Cancer Inst 1974, 52:413-473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folkman J: How is blood vessel growth regulated in normal and neoplastic tissue? GHA Clowes Memorial Award Lecture. Cancer Res 1986, 46:467-473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liotta LA, Kleinerman J, Saidel GM: Quantitative relationships of intravascular tumor cells, tumor vessels, and pulmonary metastases following tumor implantation. Cancer Res 1974, 34:997-1004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liotta LA, Kleinerman J, Saidel GM: The significance of hematogenous tumor cell clumps in the metastatic process. Cancer Res 1976, 36:889-893 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liotta LA: Tumor invasion and metastasis—role of the extracellular matrix: Rhoads Memorial Award lecture. Cancer Res 1986, 46:1-7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liotta LA, Steeg PS, Stetler-Stevenson WG: Cancer metastasis and angiogenesis: an imbalance of positive and negative regulation. Cell 1991, 64:327-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch JR, Folkman J: Tumor angiogenesis and metastasis—correlation in invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 1991, 324:1-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weidner N, Folkman J, Pozza F, Bevilaqua P, Allred E, Mili S, Gasparini G: Tumor angiogenesis: a new significant and independent prognostic indicator in early stage breast carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 1992, 84:1875-1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gasparini G, Harris AL: Clinical importance of the determination of tumor angiogenesis in breast carcinoma: much more than a new prognostic tool. J Clin Oncol 1995, 13:765-782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Obermair A, Czerwenka K, Kurz C, Laider A, Sevelda P: Tumoral microvessel density in breast cancer and its influence on recurrence-free survival. Chirurgie 1994, 65:611-615 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toi M, Kashitani J, Tominaga T: Tumor angiogenesis is an independent prognostic indicator in primary breast carcinoma. Int J Cancer 1993, 55:371-374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silberman MA, Partin AW, Velti RW, Epstein JI: Tumor angiogenesis correlates with progression after radical prostatectomy but not with pathologic stage in Gleason sum 5 to 7 adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Cancer 1997, 79:772-779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weidner N, Carroll PR, Flax J, Flumenfield W, Folkman J: Tumor angiogenesis correlates with metastasis in invasive prostate carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1993, 143:401-409 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fregene TA, Khanuja PS, Noto AC, Gehani SK, Van Egmont EM, Luz DA, Pienta FJ: Tumor-associated angiogenesis in prostate cancer. Anticancer Res 1993, 13:2377-2382 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hollingsworth HC, Kohn EC, Steinberg SM, Rothenberg ML, Meriono MJ: Tumor angiogenesis in advanced stage ovarian carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1995, 147:33-41 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maeda K, Chung Y-S, Takatsuka S, Ogawa Y, Onoda N, Sawada T, Kato Y, Nitta A, Arimoto Y, Kondo Y: Tumour angiogenesis and tumour cell proliferation as prognostic indicators in gastric carcinomas. Br J Cancer 1995, 72:319-323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takahashi Y, Kitadai Y, Bucana CD, Cleary K, Ellis LM: Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, KDR, correlates with vascularity, metastasis, and proliferation of human colon cancer. Cancer Res 1995, 55:3964-3968 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Folkman J: Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other diseases. Nat Med 1995, 1:27-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanahan D, Folkman J: Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell 1996, 86:353-364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ellis LM, Fidler IJ: Angiogenesis and metastasis. Eur J Cancer 1996, 32A:2451-2460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bielenberg DR, Bucana CD, Sanchez R, Donawho CK, Kripke ML, Fidler IJ: Molecular regulation of UV-B-induced cutaneous angiogenesis. J Invest Dermatol 1998, 3:864-872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bielenberg DR, Bucana CD, Sanchez R, Mulliken JB, Folkman J, Fidler IJ: Progressive growth of infantile cutaneous hemangiomas is directly correlated with hyperplasia and angiogenesis of adjacent epidermis and inversely correlated with expression of endogenous angiogenesis inhibitor, IFN-β. Int J Oncol 1999, 14:401-408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morikawa K, Walker SM, Jessup M, Fidler IJ: In vitro selection of highly metastatic cells from surgical specimens of different primary human colon carcinomas implanted into nude mice. Cancer Res 1988, 48:1943-1948 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morikawa K, Walker SM, Nakajima M, Pathak S, Jessup JM, Fidler IJ: Influence of organ environment on the growth, selection, and metastasis of human colon carcinoma cells in nude mice. Cancer Res 1988, 48:6863-6871 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong Z, Radinsky R, Fan D, Tsan R, Bucana CD, Wilmanns C, Fidler IJ: Organ-specific modulation of steady-state mdr gene expression and drug resistance in murine colon cancer cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 1994, 86:913-920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Radinsky R, Bucana CD, Ellis LM, Sanchez R, Cleary KR, Brigati DJ, Fidler IJ: A rapid colorimetric in situ messenger RNA hybridization technique for analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor in paraffin-embedded surgical specimens of human colon carcinomas. Cancer Res 1993, 53:937-943 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ullrich A, Coussens L, Hayflick JS, Dull TJ, Gray A, Tam AW, Lee J, Yarden Y, Libermann TA, Schlessinger J, Downward J, Mayes ELV, Whittle N, Waterfield MD, Seeburg PH: Human epidermal growth factor receptor cDNA sequence and aberrant expression of the amplified gene in A431 epidermoid carcinoma cells. Nature 1984, 309:418-428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh RK, Bucana CD, Gutman M, Fan D, Wilson MR, Fidler IJ: Organ site-dependent expression of basic fibroblast growth factor in human renal cell carcinoma cells. Am J Pathol 1994, 145:365-374 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rogelj S, Weinberg RA, Fanning P, Klagsbrun M: Basic fibroblast growth factor fused to a signal peptide transforms cells. Nature 1988, 331:173-175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matsushima K, Morishita K, Yoshimura T, Lavu S, Kobayashi Y, Lew W, Appela E, Kung HF, Leonard EJ, Oppenheim JJ: Molecular cloning of a human monocyte-derived neutrophil chemotactic factor (MDNCF) and the induction of MDNCF mRNA by interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor. J Exp Med 1988, 167:1883-1893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh RK, Gutman M, Radinsky R, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ: Expression of interleukin-8 correlates with the metastatic potential of human melanoma cells in nude mice. Cancer Res 1994, 54:3242-3247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leung DW, Cachianes G, Kuang WJ, Goeddel DV, Ferrara N: Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science 1989, 246:1306-1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tischer E, Mitchell R, Hartman T, Silva M, Gospodarowicz D, Fiddes JC, Abraham JA: The human gene for vascular endothelial growth factor: multiple protein forms are encoded through alternative exon splicing. J Biol Chem 1991, 266:11946-11954 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pearson WR, Lipman DJ: Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1988, 85:2444-2448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park C-S, Manahan LJ, Brigati DJ: Automated molecular pathology: one hour in situ DNA hybridization. J Histotechnol 1991, 14:219-229 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Caruthers MH, Beaucage SL, Efcavitch JW, Fisher EF, Goldman RA, deHaseth P, Mandecki W, Matteucci MD, Rosendahl MS, Stabinsky Y: Chemical synthesis and biological studies on mutated gene-control regions. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol 1983, 1:411-418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bucana CD, Radinsky R, Dong Z, Sanchez R, Brigati DJ, Fidler IJ: A rapid colorimetric in situ mRNA hybridization technique using hyperbiotinylated oligonucleotide probes for analysis of mdr-1 in mouse colon carcinoma cells. J Histochem Cytochem 1993, 41:499-506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reed JA, Manahan LJ, Park CS, Brigati DJ: Complete one-hour immunocytochemistry based on capillary action. Biotechniques 1992, 13:434-443 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xie K, Wang Y, Huang S, Xu L, Bielenberg D, Salas T, McConkey DJ, Jiang W, Fidler IJ: Nitric oxide-mediated apoptosis of K-1735 melanoma cells is associated with downregulation of Bcl-2. Oncogene 1997, 15:771-779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kumar R, Kuniyasu H, Bucana CD, Wilson MR, Fidler IJ: Spatial and temporal distribution of angiogenic factors in tumor progression. Oncol Res 1998, 10:301-311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zar J: Biostatistical Analysis, ed 3 1996, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

- 63.Singh RK, Gutman M, Bucana CD, Sanchez R, Llansa N, Fidler IJ: Interferons alpha and beta downregulate the expression of basic fibroblast growth factor in human carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:4562-4566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bielenberg DR, McCarty MF, Bucana CD, Yuspa SH, Morgan D, Arbeit JM, Ellis LM, Cleary KR, Fidler IJ: Expression of interferon-beta is associated with growth arrest of murine and human epidermal cells. J Invest Dermatol 1999, 112:802-809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reinecker HC, MacDermott RP, Mirau S, Dignass A, Podolsky DK: Intestinal epithelial cells both express and respond to interleukin-15. Gastroenterology 1996, 111:1706-1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carson WE, Giri JG, Lindemann MJ, Linett ML, Ahdieh M, Paxton R, Anderson D, Eisenmann J, Grabstein K, Caligiuri MA: Interleukin-15 is a novel cytokine that activates human natural killer cells via components of the IL-2 receptor. J Exp Med 1994, 180:1395-1403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumar R, Yoneda J, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ: Regulation of distinct steps of angiogenesis by different angiogenic molecules. Int J Oncol 1998, 12:749-757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown LF, Olbricht SM, Berse B, Jackman RW, Matsueda G, Tognazzi KA, Manseau EJ, Dvorak HF, Van de Water L: Overexpression of vascular permeability factor (VPF/VEGF) and its endothelial cell receptors in delayed hypersensitivity skin reactions. J Immunol 1995, 154:2801-2807 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Takahashi Y, Bucana CD, Leu W: Platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factors in human colon cancer angiogenesis: role of infiltrating cells. J Natl Cancer Inst 1996, 88:1146-1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fidler IJ: Critical determinants of human colon cancer metastasis. Molecular Pathology of Gastroenterological Cancer. Edited by E Tahara. Tokyo: Springer-Verlag, 1997, pp 47–169

- 71.Yoneda J, Killion JJ, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ: Angiogenesis and growth of murine colon carcinoma are dependent on infiltrating leukocytes. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 1999, 14:221-230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dinney CPN, Bielenberg DR, Reich R, Eve BY, Perrotte P, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ: Inhibition of basic fibroblast growth factor expression, angiogenesis, and growth of human bladder carcinoma in mice by systemic interferon-alpha administration. Cancer Res 1998, 58:808-814 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Slaton JW, Perrotte P, Inoue K, Dinney CPN, Fidler IJ: Interferon-alpha-mediated downregulation of angiogenesis-related genes and therapy of bladder cancer are dependent on optimization of dose and schedule. Clin Cancer Res 1999, 5:2726-2734 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fabra A, Nakajima M, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ: Modulation of the invasive phenotype of human colon carcinoma cells by fibroblasts from orthotopic or ectopic organs of nude mice. Differentiation 1992, 52:101-110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gohji K, Fidler IJ, Tsan R, Radinsky R, von Eschenbach AC, Tsuruo T, Nakajima M: Human recombinant interferons beta and gamma decrease gelatinase production and invasion by human KG-2 renal carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer 1994, 58:380-384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kajikawa K, Yasui W, Sumiyoshi H, Yoshida K, Nakayama H, Ayhan A, Yokozaki H, Ito H, Tahara E: Expression of epidermal growth factor in human tissues: immunohistochemical and biochemical analysis. Virchows Arch A Pathol Histopathol 1991, 418:27-32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chakrabarty S, Rajagopal S, Huang S: Expression of antisense epidermal growth factor receptor RNA downmodulates the malignant behavior of human colon cancer cells. Clin Exp Metastasis 1995, 13:191-195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rajagopal S, Huang S, Mosakal TL, Lee BN, El Naggar AK, Chakrabarty S: Epidermal growth factor expression in human colon carcinomas: antisense epidermal growth factor receptor RNA downregulates the proliferation of human colon cancer cells. Int J Cancer 1995, 62:661-667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Radinsky R, Risin S, Fan D, Dong Z, Bielenberg DR, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ: Level and function of epidermal growth factor receptor predict the metastatic potential of human colon carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res 1995, 1:19-31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kuniyasu H, Ellis LM, Evans DB, Abbruzzese JL, Fenoglio CJ, Bucana CD, Cleary KR, Tahara E, Fidler IJ: Relative expression of E-cadherin and type IV collagenase genes predicts disease outcome in patients with resectable pancreatic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 1999, 5:25-33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kitadai Y, Ellis LM, Tucker SL, Greene GF, Bucana CD, Cleary KR, Takahashi Y, Tahara E, Fidler IJ: Multiparametric in situ mRNA hybridization analysis to predict disease recurrence in patients with colon carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1996, 149:1541-1551 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fidler IJ: Modulation of the organ microenvironment for the treatment of cancer metastasis (Commentary). J Natl Cancer Inst 1995, 87:1588-1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]