Abstract

The importance of the ATP-dependent transporter P-glycoprotein, which is expressed in the brush border membrane of enterocytes and in other tissues with excretory function, for overall drug disposition is well recognized. For example, induction of intestinal P-glycoprotein by rifampin appears to be the underlying mechanism of decreased plasma concentrations of P-glycoprotein substrates such as digoxin with concomitant rifampin therapy. The contribution of transporter proteins other than P-glycoprotein to drug interactions in humans has not been elucidated. Therefore, we tested in this study the hypothesis whether the conjugate export pump MRP2 (cMOAT), which is another member of the ABC transporter family, is inducible by rifampin in humans. Duodenal biopsies were obtained from 16 healthy subjects before and after nine days of oral treatment with 600 mg rifampin/day. MRP2 mRNA and protein were determined by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry. Rifampin induced duodenal MRP2 mRNA in 14 out of 16 individuals. Moreover, MRP2 protein, which was expressed in the apical membrane of enterocytes, was significantly induced by rifampin in 10 out of 16 subjects. In summary, rifampin induces MRP2 mRNA and protein in human duodenum. Increased elimination of MRP2 substrates (eg, drug conjugates) into the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract during treatment with rifampin could be a new mechanism of drug interactions.

The mucosa of the small intestine is an increasingly recognized determinant of drug disposition. 1 After oral administration coordinate activity of drug metabolism and active drug transport from the enterocytes back into the lumen of the GI tract has been shown to limit bioavailability. 1-4 In particular, the clinical importance of drug transport by the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) efflux transporter P-glycoprotein, which is located in the apical membrane of enterocytes, for oral bioavailability and elimination of clinically important drugs has clearly been established. 5-7 Moreover, inhibition or induction of P-glycoprotein function is an important mechanism of drug interactions. 8,9 In contrast to P-glycoprotein, the potential role of other transporter proteins for drug interactions in humans has not been evaluated.

An important group of human ABC transporters are the members of the MRP (multidrug resistance protein) family. They mediate transport of unconjugated amphiphilic anions and of lipophilic compounds conjugated to glutathione, glucuronate and sulfate (for review see 10,11 ). The first cloned member of this family was MRP1, which is ubiquitously expressed throughout the body. 12 MRP2, which is also termed canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter (cMOAT) is predominantly expressed at the biliary pole of hepatocytes, but has also been found in the apical brush-border membrane of proximal tubules in the kidney. 13 Moreover, MRP2 mRNA has been detected in rat and human duodenum, and MRP2 protein was found in the human colon carcinoma cell line Caco-2. 14-17 Several mutations have been identified in humans, which lead to absence of MRP2 and to a conjugated hyperbilirubinemia named Dubin-Johnson syndrome. 11 MRP2 has a similar substrate specificity in comparison to MRP1. In addition to endogenous leukotriene, C4 human or rat MRP2 have been shown to transport pharmacologically important compounds such as methotrexate, pravastatin, temocaprilat, irinotecan, and several of its phase I and phase II metabolites. 18-22

We have previously shown that expression of MRP2 can be induced in rat hepatocytes or rat hepatoma cells by the chemical carcinogen 2-acetylaminofluorene, the antineoplastic drug cisplatin, the protein-synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide, and the barbiturate phenobarbital. 23,24 Moreover, hepatic MRP2 gene expression could be induced in rhesus monkeys by treatment with the anti-estrogenic drug tamoxifen and the antibacterial agent rifampin. 25 The latter drug is known to cause severe drug interactions due to induction of both drug metabolizing enzymes (eg, CYP3A4) 4,26 and drug transporters (eg, P-glycoprotein). 8 It is not known, however, whether rifampin also affects expression of other drug transporters in human tissues, eg, in gut wall mucosa, thereby possibly contributing to drug interactions with rifampin. After concomitant therapy with the opioid morphine and the antiarrhythmic propafenone with rifampin, we observed reduced plasma concentrations of the parent compounds. 27,28 Moreover, overall urinary recoveries of these substances and their conjugates were reduced during treatment, with rifampin pointing to an increased drug elimination via bile or direct intestinal secretion into the gut. 27,28 This increased elimination could be due to increased drug transport by MRP conjugate efflux pumps, since morphine and propafenone are primarily eliminated as glucuronide and sulfate conjugates of either parent compound or phase I metabolites.

Thus, we investigated in 16 healthy volunteers whether rifampin induces expression of members of the MRP family (MRP1, MRP2) in the mucosa of the small intestine, thereby possibly providing evidence for a new type of drug interaction.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Sixteen healthy male volunteers were included in this study. No clinically significant abnormalities were found by medical history, physical examination and routine laboratory tests including complete blood count, biochemistry, and electrocardiogram. All subjects gave their written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by local ethics committees. The subjects did not take any additional medications throughout the study and refrained from consumption of caffeine and alcohol for the duration of the study. The data on intestinal expression of P-glycoprotein and pharmacokinetics of concomitantly administered substrates of P-glycoprotein, digoxin 8 to subjects 1–8, and talinolol 29 to subjects 9–16, in these subjects have previously been reported.

Study Design

After an overnight fast, the volunteers underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) without any sedation. Biopsy specimens of the duodenal mucosa were obtained and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for RNA analysis or immediately placed in formalin for immunohistochemistry. After 9 days of oral treatment with 600 mg/day rifampin (RIFA, Grünenthal, Stolberg, Germany) a second EGD was performed as described above. The first esophagogastroduodenoscopy was taken before any medication, the second esophagogastroduodenoscopy was taken 17 days after a single dose of digoxin in subjects 1 through 8 , and 2 days after the last oral dose of talinolol in subjects 9 through 16.

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) Analysis for Villin, MRP1, and MRP2

Reverse transcription of total RNA (isolation by RNeasy Total RNA System, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was performed in a reaction mixture comprising 50 mmol/L Tris/HCl, pH 8.3, 8 mmol/L MgCl2, 50 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 1 μmol/L (dT)15, 1 mmol/L dNTPs, 100 ng RNA, 10 U RNAsin (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) and 10 U Avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) in a total volume of 10 μl. After primer annealing (23°C at 10 minutes), RNA was reverse transcribed at 42°C for 2 hours before the reaction was terminated by heating for 5 minutes at 95°C.

The PCR reaction mixture comprised 20 mmol/L Tris/HCl, pH 8.4, 50 mmol/L KCl, 2.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.25 mmol/L dNTPs, 4% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), 0.4 μmol/L MRP primers, 0.2 μmol/L villin primers, 37 kBq [α32-P]dCTP, 0.625 U Taq DNA polymerase (Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany), and 2.5 μl reverse transcription mixture in a total volume of 25 μl. The template was denaturated at 95°C for 5 minutes, primers were annealed for 2 minutes and extended at 72°C for 1 minute in the first cycle, followed by 33 cycles with a denaturation and primer annealing time of 1 minute. In the final cycle, the extension time was extended to 5 minutes. The PCR products were separated on a nondenaturating polyacrylamide gel and analyzed by autoradiography. Densitometrical analysis was performed using TINA software (Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany).

The following primer pairs (MWG-Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany) were used: MRP1 sense primer GAAGACCAAGACGTATCAGGT (bases 1651–1671 of human MRP1, GenBank accession number L05628); MRP1 anti-sense primer CAATGGTCACGTAGACGGCAA (bases 1910–1890); MRP2 sense primer ACTTGTGACATCGGTAGCATG (bases 4062–4082 of human MRP2, GenBank accession number U49248); and MRP2 anti-sense primer GTGGGCGAACTCGTTTTG (bases 4556–4539). To correct for the variation in biopsy content of mature enterocytes, 30 amplification was controlled by simultaneous amplification of enterocyte-specific, constitutively expressed villin using the sense primer CAGCTAGTGAACAAGCCTGTAGAGGAGC and the antisense primer CCACAGAAGTTTGTGCTCATAGGCAC. 31 The annealing temperature was 56°C for the MRP1/villin and 52°C for the MRP2/villin multiplex PCR.

Immunohistochemistry for MRP2

Paraffin sections 2 μm thick were prepared from each duodenal specimen using standard methods. A monoclonal antibody to human MRP2 (M2III-6, Alexis, Grünberg, Germany) was used for immunostaining. MRP2 protein was detected using the labeled streptavidin-biotin method (LSAB2-Kit, horseradish peroxidase, DAKO, Hamburg, Germany). In brief, samples were pretreated for 90 seconds in boiling citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Thereafter, endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating the specimens for 5 minutes in 3% hydrogen peroxide. Sections were incubated overnight with the primary antibody (dilution 1:20) in a humid environment. After rinsing with Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4–7.6), samples were incubated for 10 minutes with the biotinylated secondary antibody (anti-mouse and anti-rabbit Ig). After rinsing with Tris-HCl buffer, a 10-minute incubation with peroxidase-labeled streptavidin and a 10-minute incubation with the chromogen 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC) were conducted. Finally, after rinsing, a hemalaun counterstaining was performed (1 minute).

Assessment of Immunohistochemical Staining

To determine the intensity of immunohistochemical staining, we used an image analysis workstation (Histoanalyzer) as previously described. 8,32 In brief, the Histoanalyzer consists of a 3CCD color video camera (Sony, Tokyo, Japan), a type 020–452.008 microscope (Leitz Aristoplan, Wetzlar, Germany) with a scanning table (Merzhäuser, Wetzlar, Germany) and a workstation (Sun Microsystems, Palo Alto, CA). Measurements were performed with a ×40 objective. Optical density (OD) was measured in the blue channel of the red/green/blue camera signal. The field of interest, the luminal membrane of the enterocytes, was labeled with a cursor mouse system, and the results are given as OD/μm. 2 As control experiments for immunohistochemical measurements, coefficients of variation for repeated measurements of the same area of interest and of different areas in the same biopsy were determined. Tenfold measurements yielded coefficients of variation of 0.2% and 19%, respectively. The analysis was carried out by one investigator in a blinded fashion.

Statistics

All data are shown as mean ± SD. Data on mRNA and protein expression before and during treatment with rifampin were compared by paired t-tests. A P value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Correlations between parameters of interest were calculated by nonparametric Spearman rank tests.

Results

MRP1 mRNA

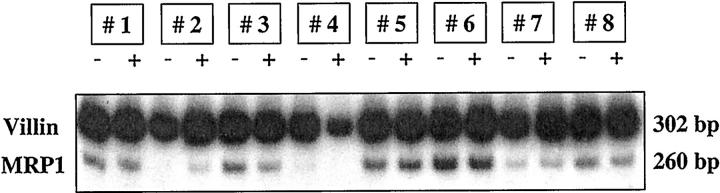

Figure 1 ▶ shows MRP1 mRNA and villin mRNA contents in duodenal biopsies from eight healthy volunteers (subjects 1–8) before and during treatment with rifampin. Mean optical density for MRP1 mRNA normalized for the respective villin content were 0.44 ± 0.24 before treatment with rifampin and 0.41 ± 0.20 after 9 days of rifampin treatment (ns).

Figure 1.

mRNA expression of MRP1 and villin in duodenal biopsies of 8 healthy volunteers before and after 9 days of treatment with 600 mg/day rifampin.

MRP2 mRNA

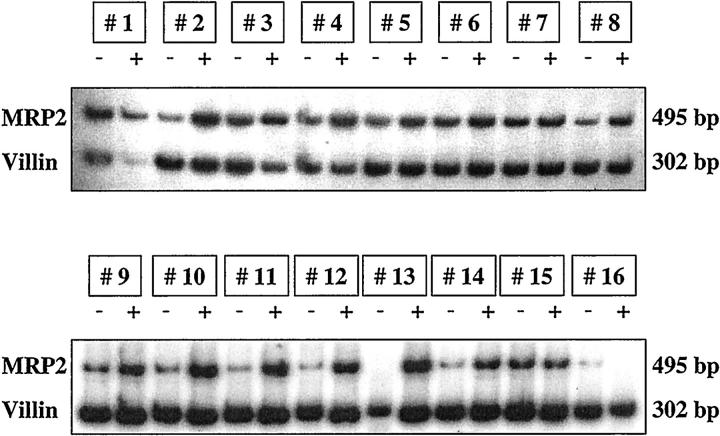

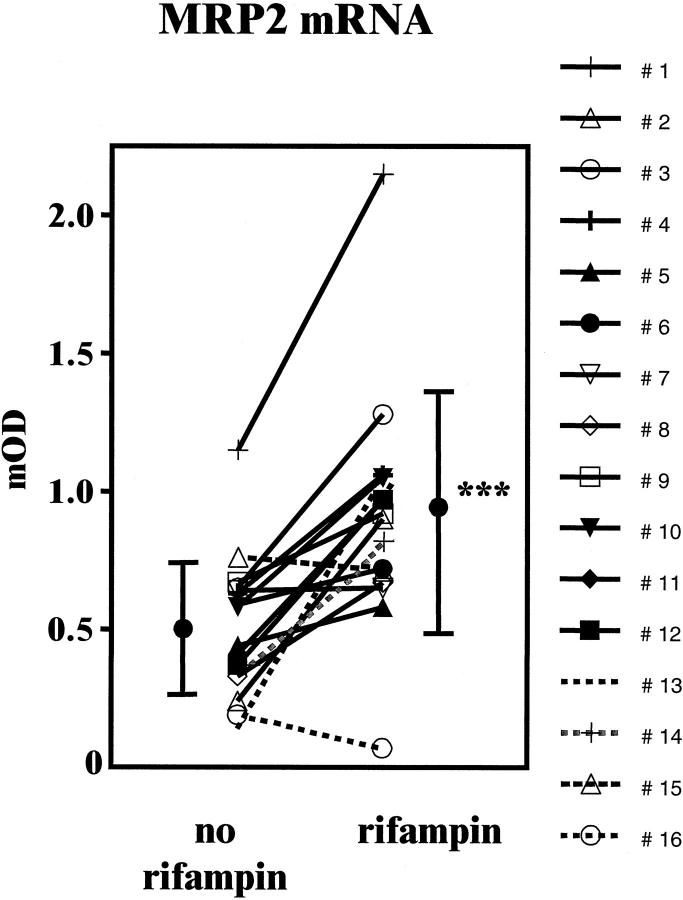

MRP2 mRNA and villin mRNA contents in duodenal biopsies before and during treatment with rifampin are shown in Figure 2 ▶ . In contrast to MRP1, MRP2 mRNA expression normalized for the respective villin content was induced by rifampin in 14 out of 16 individuals (before versus during rifampin: 0.51 ± 0.25 versus 0.91 ± 0.43, P < 0.001). Inducibility of MRP2 mRNA for each individual is shown in Figure 3 ▶ .

Figure 2.

mRNA expression of MRP2 and villin in duodenal biopsies of 16 healthy volunteers before and after 9 days of treatment with 600 mg/day rifampin.

Figure 3.

Individual data and mean values (±SD) of MRP2 mRNA expression normalized for villin mRNA in duodenal biopsies of 16 healthy volunteers before and after 9 days of treatment with 600 mg/day rifampin (*** P < 0.001).

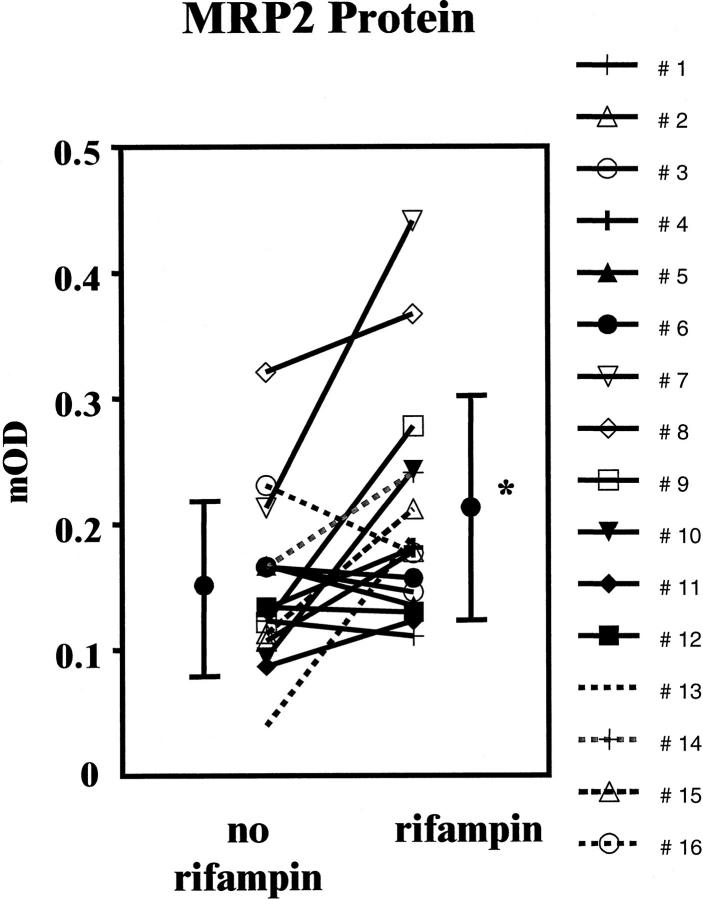

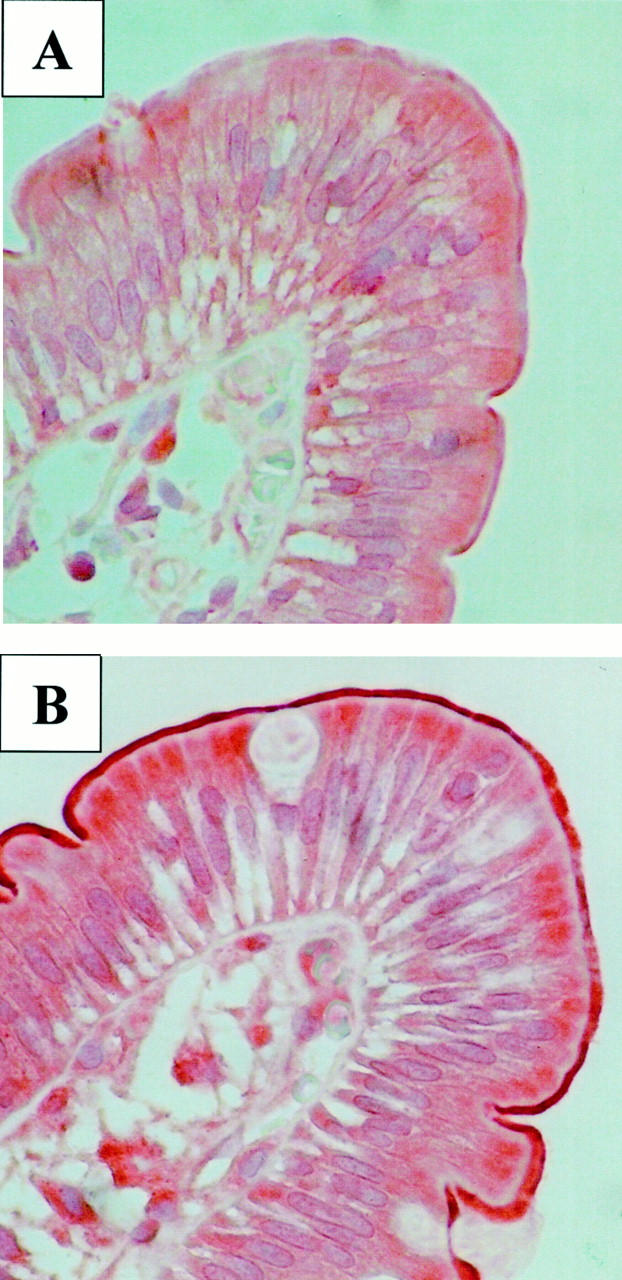

MRP2 Protein

Figure 4 ▶ shows immunohistochemical stainings for one subject before and during treatment with rifampin. Staining was predominantly observed in the apical membrane of enterocytes. Some samples showed additional moderate to intense supranuclear staining of the enterocytes. MRP2 protein expression increrased during treatment with rifampin in 10 out of 16 subjects. Expression of MRP2 assessed by immunohistochemistry was significantly increased during treatment with rifampin (before versus during rifampin: 0.15 ± 0.07 versus 0.21 ± 0.09, P < 0.05; Figure 5 ▶ ).

Figure 4.

Duodenal biopsies (villus tip, ×40, hemalaun) of one healthy volunteer (subject 15) before (A) and after 9 days of treatment with 600 mg/day rifampin (B) immunostained for MRP2.

Figure 5.

Individual data and mean values (±SD) of MRP2 protein expression in duodenal biopsies of 16 healthy volunteers before and after 9 days of treatment with 600 mg/day rifampin (* P < 0.05).

The magnitude of MRP2 protein inducibility (determined by the ratio of mOD during rifampin and mOD before rifampin) did not correlate with the magnitude of MRP2 mRNA inducibility (data not shown). However, subject 13 revealed the largest induction of both mRNA and protein of all 16 volunteers, and subject 16, in whom we actually observed a decrease in MRP2 mRNA, also showed the smallest inducibility of MRP2 protein.

Because P-glycoprotein induction by rifampin had previously been shown in the same subjects, we also analyzed whether there is a correlation between the magnitude of MRP2 and P-glycoprotein induction. 8,29 No such correlation in the magnitude of induction of these two transporters was found both on mRNA and protein level (data not shown).

Discussion

Our data indicate that human MRP2, which is expressed in the apical membrane of enterocytes of the small intestine, is inducible by treatment with rifampin. A significant effect of rifampin was detected for both MRP2 mRNA and protein expression. MRP2 mRNA has previously been found in human and rat small intestine and in the human colon carcinoma cell line Caco-2. 14-17 MRP2 protein and MRP-mediated transport activity was also detected in Caco-2 cells. 17,33 Similar to our findings in humans, MRP2 was inducible in liver of non-human primates by 7 days of oral treatment with rifampin (15 mg/kg/day). 25

Rifampin is not the only substance affecting MRP2 expression. In primary cultures of rat hepatocytes we previously found an induction of MRP2 mRNA and protein after treatment with 2-acetylaminofluorene, cisplatin, and cycloheximide with possible impact on the acquisition of multidrug resistance during chemotherapy of tumors and the process of chemical carcinogenesis in the liver. 23 Recently, it was reported independently by two groups that rat MRP2 is also inducible by dexamethasone through a mechanism that did not appear to involve the classical glucocorticoid receptor pathway. 34,35 Moreover, MRP2 expression in Caco-2 cells could be induced by the antioxidants quercetin and t-buthylhydroquinone. 36

The importance of our present findings is highlighted by the fact that rifampin causes numerous drug interactions leading to reduced plasma concentrations of concomitantly administered drugs and frequently to loss of therapeutic effects. 37 One important mechanism of these drug interactions is induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes such as CYP3A4 in the small intestine and liver. However, there have been drug interactions that cannot be explained by induction of cytochrome P450 enzymes, such as interactions of rifampin with digoxin, morphine, and propafenone. 8,27,28 Although the digoxin-rifampin interaction could be attributed to induction of intestinal P-glycoprotein, the underlying mechanism of the two latter interactions has not yet been fully elucidated. It is evident that both drugs are eliminated from the body primarily as parent compound or phase I metabolites conjugated to glucuronate or sulfate. It can be speculated that reduced morphine and propafenone plasma concentrations and reduced overall urinary recovery during treatment with rifampin are due, at least in part, to induction of MRP2 efflux transporter in enterocytes, thereby leading to an increased elimination of these drugs into the gut. It cannot be ruled out, however, that induction of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and of phase I drug metabolizing enzymes by rifampin also contributed to decreased plasma concentrations of morphine and propafenone. Interestingly, the camptothecin derivative irinotecan, which has recently been introduced in treatment of colorectal cancer as well as its active metabolite and several of its phase II metabolites, are substrates of MRP2. 19,21 Since MRP2 is expressed in colon carcinoma cells, 38 it will be important to elucidate the role of individual MRP2 function in tumor and healthy tissues for anticancer and side effects (diarrhea) of irinotecan.

Basal expression of rat mrp2 was recently shown to depend on two sequences in the 5′-flanking region of the gene comprising a Y-box and a Sp1 site, 24 whereas a putative binding site for CEBPβ was found to contribute to the basal expression of human MRP2. 39 In our study, inducibility of intestinal MRP2 by rifampin was not observed in all individuals. Subject 16 did not have any increase in MRP2 mRNA and protein expression, whereas subject 13 had a major invcrease of MRP2 mRNA and protein during traetment with rifampin. Recently the transcription factors GR 40 and PXR 41-43 have been associated with rifampin induction. Four imperfect potential PXR binding sites can be found in the MRP2 promoter sequence. 39 Goodwin et al have demonstrated functionality of binding sites with mismatches and interplay of different AG G/T TCA repeat motifs in the CYP3A4 upstream region. 43 Furthermore, it has been shown that rat MRP2 is induced by dexamethasone, clotrimazole, PCN, and phenobarbital. 24,34 These substances are activators of rat PXR. 44 Therefore, the similarity between induction of CYP3A and MRP2 genes and the presence of PXR mRNA and PXR protein in human doudenal enterocytes (Burk O, unpublished observations) support the hypothesis that PXR might be involved in MRP2 induction by rifampin.

In contrast to MRP2, MRP1 gene expression was not inducible by rifampin in subjects 1 through 8. Two potential imperfect AG G/T TCA repeat motifs can also be found in the MRP1 promoter sequence. 45 For full inducibility, existence and interplay of several sites are necessary, 43 so we can speculate that perhaps there are too few binding sites in the MRP1 promoter. Furthermore, the potential sites are all imperfect, so we cannot decide a priori whether or not they are functional. Further experiments will be required to analyze the functionality of every potential binding site to clarify the difference in inducibility of MRP1 and MRP2.

In summary, MRP2 was identified as a transporter protein expressed in the apical membrane of enterocytes that is inducible by rifampin. Further studies will clarify the importance of intestinal MRP2 for drug disposition and drug interactions.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Martin F. Fromm, M.D., Dr. Margarete Fischer-Bosch-Institute of Clinical Pharmacology, Auerbachstr. 112, 70376 Stuttgart, Germany. E-mail: martin.fromm@ikp-stuttgart.de.

Supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FR 1298/2–1, Bonn) and the Robert Bosch Foundation (Stuttgart, Germany).

References

- 1.Watkins PB: The barrier function of CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein in the small bowel. Adv Drug Del Rev 1997, 27:161-170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolars JC, Awni WM, Merion RM, Watkins PB: First-pass metabolism of cyclosporin by the gut. Lancet 1991, 338:1488-1490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thummel KE, O’Shea D, Paine MF, Shen DD, Kunze KL, Perkins JD, Wilkinson GR: Oral first-pass elimination of midazolam involves both gastrointestinal and hepatic CYP3A-mediated metabolism. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1996, 59:491-502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fromm MF, Busse D, Kroemer HK, Eichelbaum M: Differential induction of prehepatic and hepatic metabolism of verapamil by rifampin. Hepatology 1996, 24:796-801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim RB, Fromm MF, Wandel C, Leake B, Wood AJJ, Roden DM, Wilkinson GR: The drug transporter P-glycoprotein limits oral absorption and brain entry of HIV-1 protease inhibitors. J Clin Invest 1998, 101:289-294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sparreboom A, van Asperen J, Mayer U, Schinkel AH, Smit JW, Meijer DK, Borst P, Nooijen WJ, Beijnen JH, van Tellingen O: Limited oral bioavailability and active epithelial excretion of paclitaxel (Taxol) caused by P-glycoprotein in the intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1997, 94:2031-2035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lown KS, Mayo RR, Leichtman AB, Hsiao HL, Turgeon DK, Schmiedlin R, Brown MB, Guo W, Rossi SJ, Benet LZ, Watkins PB: Role of intestinal P-glycoprotein (mdr1) in interpatient variation in the oral bioavailability of cyclosporine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1997, 62:248-260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greiner B, Eichelbaum M, Fritz P, Kreichgauer H-P, von Richter O, Zundler J, Kroemer HK: The role of intestinal P-glycoprotein in the interaction of digoxin and rifampin. J Clin Invest 1999, 104:147-153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fromm MF, Kim RB, Stein CM, Wilkinson GR, Roden DM: Inhibition of P-glycoprotein-mediated drug transport: a unifying mechanism to explain the interaction between digoxin and quinidine. Circulation 1999, 99:552-557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borst P, Evers R, Kool M, Wijnholds J: The multidrug resistance protein family. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999, 1461:347-357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.König J, Nies AT, Cui Y, Leier I, Keppler D: Conjugate export pumps of the multidrug resistance protein (MRP) family: localization, substrate specificity, and MRP2-mediated drug resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta 1999, 1461:377-394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole SP, Bhardwaj G, Gerlach JH, Mackie JE, Grant CE, Almquist KC, Stewart AJ, Kurz EU, Duncan AM, Deeley RG: Overexpression of a transporter gene in a multidrug-resistant human lung cancer cell line. Science 1992, 258:1650-1654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaub TP, Kartenbeck J, König J, Vogel O, Witzgall R, Kriz W, Keppler D: Expression of the conjugate export pump encoded by the mrp2 gene in the apical membrane of kidney proximal tubules. J Am Soc Nephrol 1997, 8:1213-1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paulusma CC, Bosma PJ, Zaman GJ, Bakker CT, Otter M, Scheffer GL, Scheper RJ, Borst P, Oude Elferink R: Congenital jaundice in rats with a mutation in a multidrug resistance-associated protein gene. Science 1996, 271:1126-1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito K, Suzuki H, Hirohashi T, Kume K, Shimizu T, Sugiyama Y: Molecular cloning of canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter defective in EHBR. Am J Physiol 1997, 272:G16-G22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kool M, de Haas M, Scheffer GL, Scheper RJ, van Eijk MJ, Juijn JA, Baas F, Borst P: Analysis of expression of cMOAT (MRP2), MRP3, MRP4, and MRP5, homologues of the multidrug resistance-associated protein gene (MRP1), in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 1997, 57:3537-3547 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walle UK, Galijatovic A, Walle T: Transport of the flavonoid chrysin and its conjugated metabolites by the human intestinal cell line Caco-2. Biochem Pharmacol 1999, 58:431-438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hooijberg JH, Broxterman HJ, Kool M, Assaraf YG, Peters GJ, Noordhuis P, Scheper RJ, Borst P, Pinedo HM, Jansen G: Antifolate resistance mediated by the multidrug resistance proteins MRP1 and MRP2. Cancer Res 1999, 59:2532-2535 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chu XY, Kato Y, Ni‘inuma K, Sudo KI, Hakusui H, Sugiyama Y: Multispecific organic anion transporter is responsible for the biliary excretion of the camptothecin derivative irinotecan and its metabolites in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997, 281:304-314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugiyama Y, Kato Y, Chu X: Multiplicity of biliary excretion mechanisms for the camptothecin derivative irinotecan (CPT-11), its metabolite SN-38, and its glucuronide: role of canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter and P-glycoprotein. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1998, 42(suppl):S44-S49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishizuka H, Konno K, Naganuma H, Sasahara K, Kawahara Y, Niinuma K, Suzuki H, Sugiyama Y: Temocaprilat, a novel angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, is excreted in bile via an ATP-dependent active transporter (cMOAT) that is deficient in Eisai hyperbilirubinemic mutant rats (EHBR). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997, 280:1304-1311 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamazaki M, Akiyama S, Ni’inuma K, Nishigaki R, Sugiyama Y: Biliary excretion of pravastatin in rats: contribution of the excretion pathway mediated by canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter. Drug Metab Dispos 1997, 25:1123-1129 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kauffmann HM, Keppler D, Kartenbeck J, Schrenk D: Induction of cMrp/cMoat gene expression by cisplatin, 2- acetylaminofluorene, or cycloheximide in rat hepatocytes. Hepatology 1997, 26:980-985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kauffmann HM, Schrenk D: Sequence analysis and functional characterization of the 5′-flanking region of the rat multidrug resistance protein 2 (mrp2) gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998, 245:325-331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kauffmann HM, Keppler D, Gant TW, Schrenk D: Induction of hepatic mrp2 (cmrp/cmoat) gene expression in nonhuman primates treated with rifampicin or tamoxifen. Arch Toxicol 1998, 72:763-768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolars JC, Schmiedlin-Ren P, Schuetz JD, Fang C, Watkins PB: Identification of rifampin-inducible P450IIIA4 (CYP3A4) in human small bowel enterocytes. J Clin Invest 1992, 90:1871-1878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fromm MF, Eckhardt K, Li S, Schänzle G, Hofmann U, Mikus G, Eichelbaum M: Loss of analgesic effect of morphine due to coadministration of rifampin. Pain 1997, 72:261-267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dilger K, Greiner B, Fromm MF, Hofmann U, Kroemer HK, Eichelbaum M: Consequences of rifampicin treatment on propafenone disposition in extensive and poor metabolizers of CYP2D6. Pharmacogenetics 1999, 9:551-559 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westphal K, Weinbrenner A, Zschiesche M, Franke G, Knoke M, Oertel R, Fritz P, von Richter O, Warzok R, Hachenberg T, Kauffmann H-M, Schrenk D, Terhaag B, Kroemer HK, Siegmund W: Induction of P-glycoprotein by rifampin increases intestinal secretion of talinolol in man: a new type of drug/drug interaction. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2000, (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Lown KS, Bailey DG, Fontana RJ, Janardan SK, Adair CH, Fortlage LA, Brown MB, Guo W, Watkins PB: Grapefruit juice increases felodipine oral availability in humans by decreasing intestinal CYP3A protein expression. J Clin Invest 1997, 99:2545-2553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmiedlin-Ren P, Thummel KE, Fisher JM, Paine MF, Lown KS, Watkins PB: Expression of enzymatically active CYP3A4 by Caco-2 cells grown on extracellular matrix-coated permeable supports in the presence of 1-alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Mol Pharmacol 1997, 51:741-754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fritz P, Behrle E, Beaune P, Eichelbaum M, Kroemer HK: Differential expression of drug metabolizing enzymes in primary and secondary liver neoplasm: immunohistochemical characterization of cytochrome P4503A and glutathione-S-transferase. Histochemistry 1993, 99:443-451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirohashi T, Suzuki H, Ito K, Ogawa K, Kume K, Shimizu T, Sugiyama Y: Hepatic expression of multidrug resistance-associated protein-like proteins maintained in Eisai hyperbilirubinemic rats. Mol Pharmacol 1998, 53:1068-1075 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Courtois A, Payen L, Guillouzo A, Fardel O: Up-regulation of multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2) expression in rat hepatocytes by dexamethasone. FEBS Lett 1999, 459:381-385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demeule M, Jodoin J, Beaulieu E, Brossard M, Beliveau R: Dexamethasone modulation of multidrug transporters in normal tissues. FEBS Lett 1999, 442:208-214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bock KW, Eckle T, Ouzzine M, Fournel-Gigleux S: Coordinate induction by antioxidants of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase UGT1A6 and the apical conjugate export pump MRP2 (multidrug resistance protein 2) in Caco-2 cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2000, 59:467-470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strayhorn VA, Baciewicz AM, Self TH: Update on rifampin drug interactions, III. Arch Intern Med 1997, 157:2453-2458 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirohashi T, Suzuki H, Chu XY, Tamai I, Tsuji A, Sugiyama Y: Function and expression of multidrug resistance-associated protein family in human colon adenocarcinoma cells (Caco-2). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2000, 292:265-270 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka T, Uchiumi T, Hinoshita E, Inokuchi A, Toh S, Wada M, Takano H, Kohno K, Kuwano M: The human multidrug resistance protein 2 gene: functional characterization of the 5′-flanking region and expression in hepatic cells. Hepatology 1999, 30:1507-1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calleja C, Pascussi JM, Mani JC, Maurel P, Vilarem MJ: The antibiotic rifampicin is a nonsteroidal ligand and activator of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Nat Med 1998, 4:92-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kliewer SA, Moore JT, Wade L, Staudinger JL, Watson MA, Jones SA, McKee DD, Oliver BB, Willson TM, Zetterstrom RH, Perlmann T, Lehmann JM: An orphan nuclear receptor activated by pregnanes defines a novel steroid signaling pathway. Cell 1998, 92:73-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lehmann JM, McKee DD, Watson MA, Willson TM, Moore JT, Kliewer SA: The human orphan nuclear receptor PXR is activated by compounds that regulate CYP3A4 gene expression and cause drug interactions. J Clin Invest 1998, 102:1016-1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodwin B, Hodgson E, Liddle C: The orphan human pregnane X receptor mediates the transcriptional activation of CYP3A4 by rifampicin through a distal enhancer module. Mol Pharmacol 1999, 56:1329-1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones SA, Moore LB, Shenk JL, Wisely GB, Hamilton GA, McKee DD, Tomkinson NC, LeCluyse EL, Lambert MH, Willson TM, Kliewer SA, Moore JT: The pregnane X receptor: a promiscuous xenobiotic receptor that has diverged during evolution. Mol Endocrinol 2000, 14:27-39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu Q, Center MS: Cloning and sequence analysis of the promoter region of the MRP gene of HL60 cells isolated for resistance to adriamycin. Cancer Res 1994, 54:4488-4492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]