Abstract

p53 and tau are both associated with neurodegenerative disorders. Here, we show by Western blotting that p53 is upregulated approximately 2-fold in the superior temporal gyrus of Alzheimer's patients compared to healthy elderly control subjects. Moreover, p53 was found to induce phosphorylation of human 2N4R tau at the tau-1/AT8 epitope in HEK293a cells. Confocal microscopy revealed that tau and p53 were spatially separated intracellularly. Tau was found in the cytoskeletal compartment, whilst p53 was located in the nucleus, indicating that the effects of p53 on tau phosphorylation are indirect. Collectively, these findings have ramifications for neuronal death associated with Alzheimer's disease and other tauopathies.

Keywords: p53, Tau, Microtubules, Alzheimer's disease

Tau is the major microtubule-associated protein (MAP) in neurons and functions in the formation and maintenance of axons by influencing microtubule organization. In adult human brain, there are six isoforms of tau generated by alternative mRNA-splicing. Tau has zero, one or two amino-terminal inserts and either three or four repeats of a microtubule-binding domain situated towards the carboxy-terminus [7]. Tau splicing and phosphorylation are developmentally regulated. Only the shortest tau isoform is expressed in foetal brain [8] and foetal tau is more extensively phosphorylated than tau from adult brain [10,15]. Phosphorylated tau is less efficient at promoting microtubule assembly [12,14] and elevated levels of phosphorylated tau correlate with increased microtubule dynamics associated with plasticity during development [1]. Increased tau phosphorylation is also a characteristic feature of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and tauopathies such as frontotemporal dementia with Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17) [7]. In these disorders, normally soluble tau is present as paired-helical filaments (PHFs), which in turn aggregate to form neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs).

p53 is a tumor suppressor protein, which induces cell cycle arrest or apoptosis. Normally, p53 is maintained at low levels by murine double minute-2 (MDM2) or the human homologue (HDM2), which inhibit the transcriptional activity of p53 and promote degradation of p53 via the proteasome [2]. Activation of p53 involves stabilization of the protein by post-translational modifications, which disrupts the interaction between p53 and MDM2. Several studies have reported an increase in p53 immunoreactivity in sporadic AD [11,13] especially in subpopulations of cortical neurons undergoing neurofibrillary degeneration [5]. Furthermore, p53−/− mice display a reduction in tau phosphorylation [6]. These findings prompted us to investigate the effects of p53 on tau phosphorylation in vitro.

The following antibodies and plasmids were used in this study: mouse anti-β actin, which was from Sigma (UK). Rabbit anti-total tau from Dakocytomation (UK). Tau-1 monoclonal antibody, which was a gift from Professor L. Binder (Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer's Disease Center, Northwestern University, USA). PHF-1 monoclonal antibody, which was a kind gift from Dr. P. Davies (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, NY, USA). AT270 and AT8 monoclonal antibodies, goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (USA). Anti-p53 (clone DO7) was from Novocastra Laboratories (UK). Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG were from Invitrogen (UK). p53, which was a generous gift from Dr B. Vogelstein (John Hopkins, USA). 2N4R tau was a gift from Professor J. Woodgett (Ontario Cancer Institute, Toronto, Canada) BAX-Luc and p21waf-Luc were from Dr. T. Soussi (Universite P.M. Curie, Paris).

Human embryonic kidney 293a cells (HEK293a) (Quantum Biotechnologies, Canada) were cultured in low glucose Dulbecco's modified essential medium (Invitrogen, UK) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Autogen Bioclear, UK), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 IU penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin.

Post mortem brain tissue from the superior temporal gyrus was provided by the MRC London Brain Bank for Research on Neurodegenerative Diseases. Use of human tissue was approved by the South London and Maudsley Research Ethics Committee and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Control subjects had no history or symptoms of neurological disorder. All AD cases were neuropathologically confirmed, using conventional histopathological techniques and diagnosis was performed using the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD) criteria. Total protein was extracted (50 μg) from 17 non-demented elderly controls and 53 AD cases and p53 levels were determined by Western blotting using a specific anti-p53 antibody (1:1000). p53 expression was normalised to β-tubulin by standard densitometric procedures. Values for control and AD were compared using an unpaired two-tailed t-test, *p < 0.05. For tau phosphorylation experiments HEK293a cells plated in a 6 well plate were transfected with OptiMEM (100 μl) containing FuGene 6 (5 μl) and cDNA constructs (500 ng of each) encoding human 2N4R tau independently or in combination with p53. Cells lysates were harvested 24 h after transfection. Western blotting was performed using the following primary antibodies; rabbit anti-total tau (1:10,000), mouse anti-phospho-Ser199/Ser202/Thr205 (tau-1, 1:1000), mouse-anti-phospho-Ser202/Thr205 (AT8, 1:500), mouse anti-phospho-Ser396/Ser404 (PHF-1) (1:1000) or mouse anti-phospho-Thr181 (AT270, 1:1000) according to standard protocols with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham Pharmacia, UK). To ensure equal loading membranes were reprobed with mouse anti-β actin. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

For sub-cellular localisation experiments HEK293a cells were transfected with human 2N4R tau independently or in combination with p53 as described above. The following day the cells were fixed in ice-cold methanol and stained according to standard protocols. Cells were incubated with rabbit anti-total tau (1:500) or mouse anti-p53 (1:250) before being incubated with the appropriate fluorescent secondary antibody (1:200). Nuclei were counter-stained with Hoescht 33342. Immunofluorescence was captured using a Zeiss LSM510 meta-confocal microscope. All experiments were performed in triplicate; therefore, figures shown are representative of a single experiment.

The transcriptional effects of p53 were examined by reporter gene assay. Four wells of HEK293a cells plated in a 48 well plate were transfected by adding 25 μl of a master-transfection mix to the culture medium. The master-mix contained 100 μl of OptiMEM (Invitrogen, UK), 4 μl FuGene 6 (Roche, UK), 400 ng of firefly either BAX-Luc or p21waf-Luc (luciferase-based reporter DNA), 50 ng phTK-Renilla luciferase (Promega, UK) to control for transfection efficiency and 800 ng of p53. Appropriate amounts of empty vector DNA were included where necessary to maintain constant DNA concentrations. Twenty-four hours post-transfection the firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were sequentially measured using Dual-Glo reagents (Promega, UK) in a Wallac Trilux 1450 Luminometer (Perkin-Elmer, UK). Firefly values were divided by the Renilla value from the same well to control for non-specific effects. Data for each set of four replica transfections was averaged, the control in each set normalized to 1 and data presented as fold increases over control. Each assay was repeated three times.

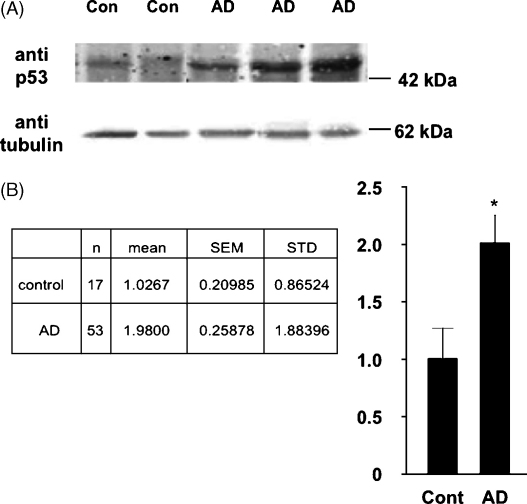

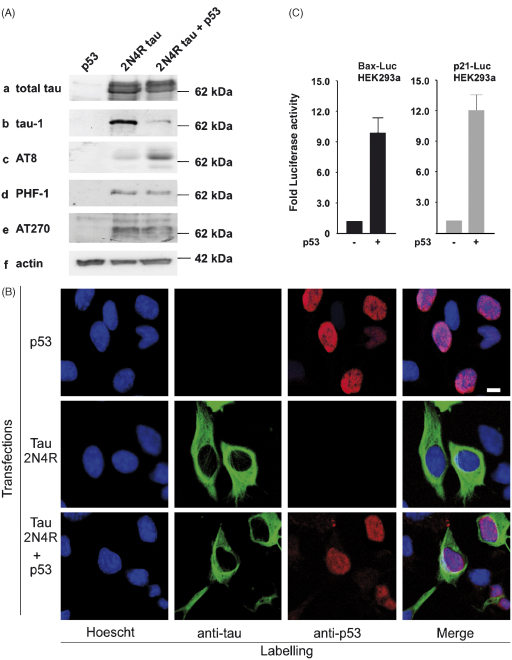

p53 levels were quantified by Western blotting in the superior temporal gyrus from a large cohort of patients comprising of 53 AD cases and 17 control subjects. In accordance with previous reports that had examined smaller patient numbers [5,11,13] we found that p53 immunoreactivity was indeed significantly elevated in tissue from AD patients compared to healthy elderly controls (Fig. 1A). Densitometry revealed an approximate 2-fold increase in p53 expression in AD (Fig. 1B). Next we explored the effects of p53 on tau phosphorylation. The 2N4R isoform of human tau was exogenously expressed in HEK293a cells (which do not contain endogenous tau) alone or in combination with p53. Co-expression of tau with p53 resulted in an increase in tau phosphorylation as demonstrated by a decrease in electrophoretic mobility using an anti-total tau antibody, which detects all tau isoforms independently of their phosphorylation state (Fig. 2A, panel a). Tau can be phosphorylated at a number of serine (Ser) and threonine (Thr) residues; therefore, we subsequently used a number of phosphorylation-specific anti-tau antibodies to examine the effects of p53 on tau further. There was an almost complete reduction of tau-1 immunoreactivity in HEK293a cells co-transfected with p53 and tau in comparison to cells expressing tau alone (Fig. 2A, panel b). Tau-1 recognises a number of amino acids including Ser199, Ser202 and Thr205 [4] when de-phosphorylated, therefore a decrease in immunoreactivity at this site reflects an increase in tau phosphorylation. Consistent with this, p53 induced an increase in tau phosphorylation as evidenced using the AT8 antibody, which recognizes tau phosphorylated at Ser202/Thr205 (Fig. 2A, panel c). In contrast, no changes in tau phosphorylation in the presence of p53 were observed using PHF-1 (Fig. 2A, panel d) or AT270 (Fig. 2A, panel e) monoclonal antibodies. Immunoblotting for β-actin illustrated that equal amounts of protein had been loaded across lanes (Fig. 2A, panel f).

Fig. 1.

p53 expression is increased in AD compared to control patients. (A) Total protein extracted from the superior temporal gyrus (50 μg) was analyzed for p53 levels from 17 non-demented elderly controls and 53 AD cases. The Western blot represents p53 expression levels and β-tubulin levels as a loading control from 2 control (‘con’) and 3 AD patients. (B) Densitometry values for p53 were normalised to β-tubulin levels. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test, *p < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

p53 induces tau phosphorylation in HEK293a cells. (A) Exogenous 2N4R tau was expressed in HEK293a cells alone or with p53. Lysates were subjected to Western blotting and probed with a panel of tau antibodies as indicated. Blots were reprobed with anti-β actin to ensure equal loading. (B) Sub-cellular distribution of tau and p53 in HEK293a cells. Exogenous 2N4R tau and p53 were co-expressed in HEK293a cells. Tau (green) was found in the cytoskeletal compartment whilst p53 (red) was present in the nucleus. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoescht (blue). Scale bar represents 10 μm. (C) p53 activates BAX-Luc and p21waf-Luc in HEK293a cells. HEK293a cells were transfected with either BAX-Luc or p21waf-Luc with either empty vector or p53 as indicated. Twenty-four hours post-transfection cells were lysed and luciferase activity determined.

Confocal microscopy demonstrated that p53 and tau are compartmentally separated (Fig. 2B). p53 (red) exhibits a diffuse nuclear localisation, whilst tau (green) is present in the cytoskeletal compartment when expressed both independently and in combination. This suggests that the effects of p53 on tau phosphorylation are indirect and most likely attributable to the transcription of a p53 target gene. We verified the transcriptional properties of p53 in HEK293a cells using BAX-Luc and p21waf-Luc (Fig. 2C), which are luciferase reporter constructs derived from known p53 target genes.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that p53 is upregulated in the superior temporal gyrus in AD and that p53 induces tau phosphorylation at the tau-1/AT8 epitope in HEK293a cells. We infer that the effects of p53 on tau phosphorylation are indirect as evidenced by the compartmental segregation of the two proteins. Therefore, pathological and sustained expression of p53 in adult brain might promote excessive and prolonged tau phosphorylation, which in turn might precipitate the formation of NFTs and neuronal death. Interestingly, we [9] have previously shown that TAp73 induces tau phosphorylation in HEK293a cells at the tau-1 and at the PHF-1 epitopes, which suggests that a similar mechanism of action might be shared by other p53 family members. Pertinent to our observations, it has recently been demonstrated that the expression of p53 is in part mediated by the transcriptionally active intracellular domain (ICD) of the β-amyloid precursor protein (APP), the generation of which is dependent upon the γ-secretase activities of presenilin-1 [3]. It is feasible then that in sporadic and familial AD, which both exhibit increased Aβ production, the concomitant increase in APP-ICD generation could lead to an increase in p53 expression and increased tau phosphorylation. Such a scheme forges a link between the two neuropathological hallmarks of AD, senile plaques and NFTs. In addition, it has also recently been demonstrated that Aβ itself, in particular the 42 amino acid form, binds the p53 promoter and enhances transcription [13]. Thus, p53 seems to play a pivotal role in AD, implying that modulation of cell death pathways might be of therapeutic benefit in AD and indeed in other age related neurological disorders.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust, the MRC and the BBSRC.

References

- 1.Brion J.P., Octave J.N., Couck A.M. Distribution of the phosphorylated microtubule-associated protein tau in developing cortical neurons. Neuroscience. 1994;63:895–909. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks C.L., Gu W. p53 ubiquitination: Mdm2 and beyond. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa C.A., Sunyach C., Pardossi-Piquard R., Sevalle J., Vincent B., Boyer N., Kawarai T., Girardot N., George-Hyslop P., Checler F. Presenilin-dependent gamma-secretase-mediated control of p53-associated cell death in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:6377–6385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0651-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis P.K., Johnson G.V.W. The microtubule binding of Tau and high molecular weight Tau in apoptotic PC12 cells is impaired because of altered phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:35686–35692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de la Monte S.M., Sohn Y.K., Wands J.R. Correlates of p53- and Fas (CD95)-mediated apoptosis in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 1997;152:73–83. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira A., Kosik K.S. Accelerated neuronal differentiation induced by p53 suppression. J. Cell. Sci. 1996;109:1509–1516. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.6.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goedert M. Tau protein and neurodegeneration. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;15:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goedert M., Spillantini M.G., Jakes R., Rutherford D., Crowther R.A. Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1989;3:519–526. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90210-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hooper C., Killick R., Tavassoli M., Melino G., Lovestone S. TAp73[alpha] induces tau phosphorylation in HEK293a cells via a transcription-dependent mechanism. Neurosci. Lett. 2006;401:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.02.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenessey A., Yen S.H. The extent of phosphorylation of fetal tau is comparable to that of PHF-tau from Alzheimer paired helical filaments. Brain Res. 1993;629:40–46. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitamura Y., Shimohama S., Kamoshima W., Matsuoka Y., Nomura Y., Taniguchi T. Changes of p53 in the brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;232:418–421. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu Q., Wood J.G. Functional studies of Alzheimer's disease tau protein. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:508–515. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00508.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohyagi Y., Asahara H., Chui D.H., Tsuruta Y., Sakae N., Miyoshi K., Yamada T., Kikuchi H., Taniwaki T., Murai H., Ikezoe K., Furuya H., Kawarabayashi T., Shoji M., Checler F., Iwaki T., Makifuchi T., Takeda K., Kira J.i., Tabira T. Intracellular Aβ42 activates p53 promoter: a pathway to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J. 2004 doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2637fje. (04-2637fje) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trinczek B., Biernat J., Baumann K., Mandelkow E.M., Mandelkow E. Domains of tau protein, differential phosphorylation, and dynamic instability of microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1995;6:1887–1902. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.12.1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe A., Hasegawa M., Suzuki M., Takio K., Morishima-Kawashima M., Titani K., Arai T., Kosik K.S., Ihara Y. In vivo phosphorylation sites in fetal and adult rat tau. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:25712–25717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]