Abstract

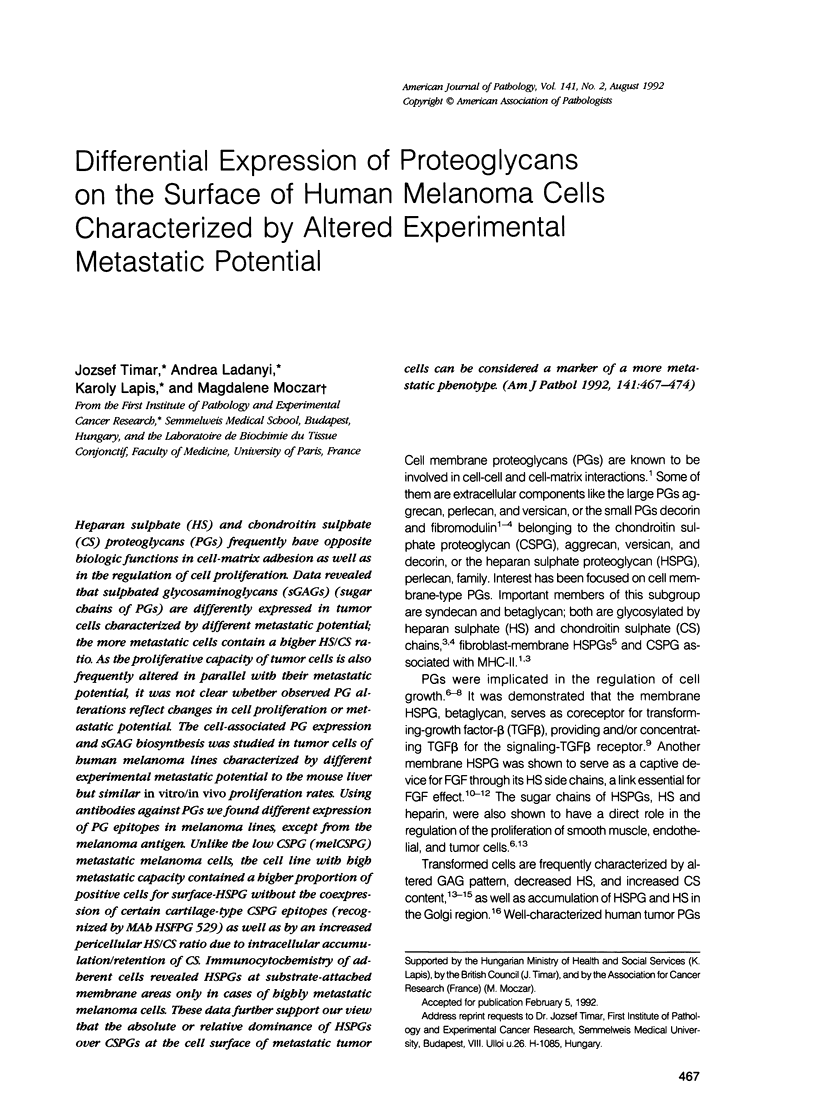

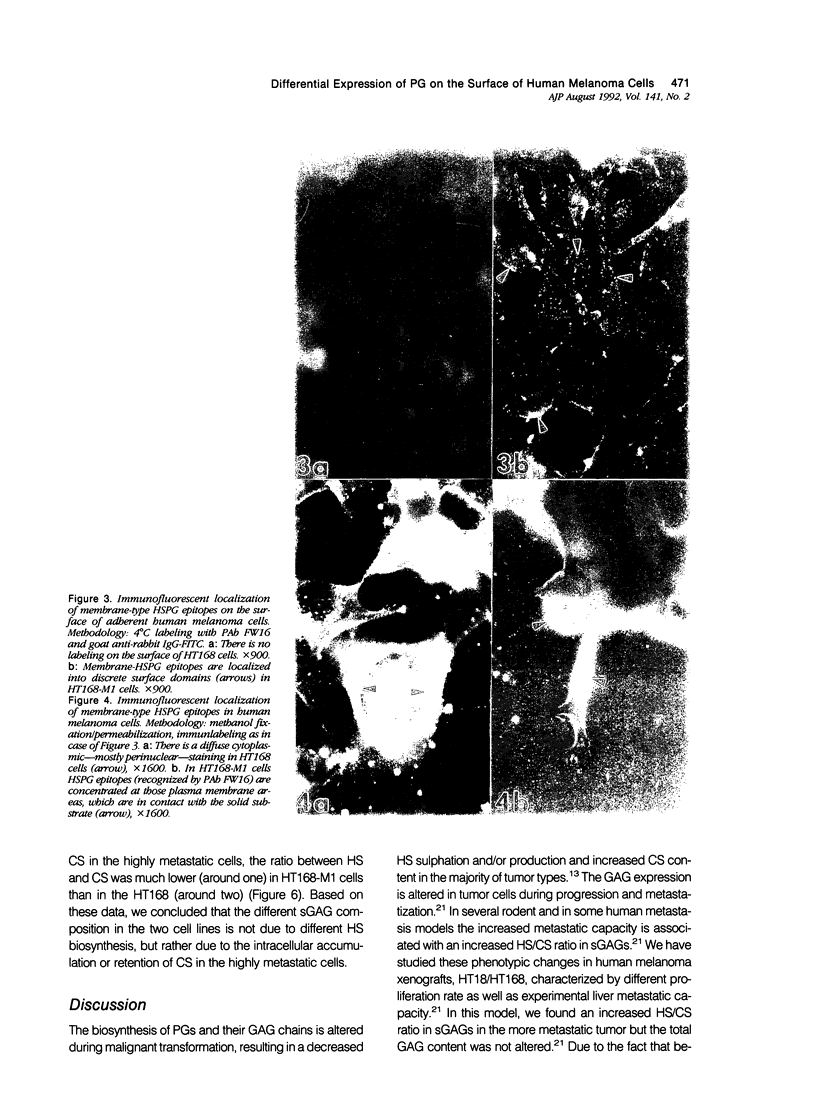

Heparan sulphate (HS) and chondroitin sulphate (CS) proteoglycans (PGs) frequently have opposite biologic functions in cell-matrix adhesion as well as in the regulation of cell proliferation. Data revealed that sulphated glycosaminoglycans (sGAGs) (sugar chains of PGs) are differently expressed in tumor cells characterized by different metastatic potential; the more metastatic cells contain a higher HS/CS ratio. As the proliferative capacity of tumor cells is also frequently altered in parallel with their metastatic potential, it was not clear whether observed PG alterations reflect changes in cell proliferation or metastatic potential. The cell-associated PG expression and sGAG biosynthesis was studied in tumor cells of human melanoma lines characterized by different experimental metastatic potential to the mouse liver but similar in vitro/in vivo proliferation rates. Using antibodies against PGs we found different expression of PG epitopes in melanoma lines, except from the melanoma antigen. Unlike the low CSPG (melCSPG) metastatic melanoma cells, the cell line with high metastatic capacity contained a higher proportion of positive cells for surface-HSPG without the coexpression of certain cartilage-type CSPG epitopes (recognized by MAb HSFPG 529) as well as by an increased pericellular HS/CS ratio due to intracellular accumulation/retention of CS. Immunocytochemistry of adherent cells revealed HSPGs at substrate-attached membrane areas only in cases of highly metastatic melanoma cells. These data further support our view that the absolute or relative dominance of HSPGs over CSPGs at the cell surface of metastatic tumor cells can be considered a marker of a more metastatic phenotype.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andres J. L., Stanley K., Cheifetz S., Massagué J. Membrane-anchored and soluble forms of betaglycan, a polymorphic proteoglycan that binds transforming growth factor-beta. J Cell Biol. 1989 Dec;109(6 Pt 1):3137–3145. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry F. Proteoglycans: structure and function. Biochem Soc Trans. 1990 Apr;18(2):197–198. doi: 10.1042/bst0180197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumol T. F., Walker L. E., Reisfeld R. A. Biosynthetic studies of proteoglycans in human melanoma cells with a monoclonal antibody to a core glycoprotein of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans. J Biol Chem. 1984 Oct 25;259(20):12733–12741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caux F., Timar J., Lapis K., Moczar M. Proteochondroitin sulphate in human melanoma cell cultures. Biochem Soc Trans. 1990 Apr;18(2):293–294. doi: 10.1042/bst0180293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caux F., Timar J., Moczar E., Lapis K., Moczar M. Cell-associated glycosaminoglycans in human melanoma cell culture. Biochem Soc Trans. 1990 Apr;18(2):294–295. doi: 10.1042/bst0180294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amore P. A. Modes of FGF release in vivo and in vitro. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1990 Nov;9(3):227–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00046362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esko J. D., Rostand K. S., Weinke J. L. Tumor formation dependent on proteoglycan biosynthesis. Science. 1988 Aug 26;241(4869):1092–1096. doi: 10.1126/science.3137658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaumenhaft R., Moscatelli D., Rifkin D. B. Heparin and heparan sulfate increase the radius of diffusion and action of basic fibroblast growth factor. J Cell Biol. 1990 Oct;111(4):1651–1659. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.4.1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J. T. The extended family of proteoglycans: social residents of the pericellular zone. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1989 Dec;1(6):1201–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(89)80072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J. T., Turnbull J. E., Lyon M. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans. Biochem Soc Trans. 1990 Apr;18(2):207–209. doi: 10.1042/bst0180207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garin-Chesa P., Beresford H. R., Carrato-Mena A., Oettgen H. F., Old L. J., Melamed M. R., Rettig W. J. Cell surface molecules of human melanoma. Immunohistochemical analysis of the gp57, GD3, and mel-CSPG antigenic systems. Am J Pathol. 1989 Feb;134(2):295–303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glant T. T., Mikecz K., Poole A. R. Monoclonal antibodies to different protein-related epitopes of human articular cartilage proteoglycans. Biochem J. 1986 Feb 15;234(1):31–41. doi: 10.1042/bj2340031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo R. V. Biosynthesis of heparan sulfate proteoglycan by human colon carcinoma cells and its localization at the cell surface. J Cell Biol. 1984 Aug;99(2):403–417. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.2.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iozzo R. V. Proteoglycans and neoplasia. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1988 Apr;7(1):39–50. doi: 10.1007/BF00048277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjellén L., Lindahl U. Proteoglycans: structures and interactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:443–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.002303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopper L., Bankfalvi A., Mihalik R., Glant T. T., Timar J. Proteoglycan-targeted antibodies as markers on non-Hodgkin lymphoma xenografts. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1990;32(2):137–142. doi: 10.1007/BF01754211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladányi A., Tímár J., Paku S., Molnár G., Lapis K. Selection and characterization of human melanoma lines with different liver-colonizing capacity. Int J Cancer. 1990 Sep 15;46(3):456–461. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910460322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga E., Shinkai H., Nusgens B., Lapière C. M. Acidic glycosaminoglycans, isolation and structural analysis of a proteodermatan sulfate from dermatosparactic calf skin. Coll Relat Res. 1987 Feb;6(6):467–479. doi: 10.1016/s0174-173x(87)80046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts D. D. Interactions of thrombospondin with sulfated glycolipids and proteoglycans of human melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 1988 Dec 1;48(23):6785–6793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A. H., Herlyn M., Ernst C. S., Guerry D., Bennicelli J., Ghrist B. F., Atkinson B., Koprowski H. Immunoassay for melanoma-associated proteoglycan in the sera of patients using monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies. Cancer Res. 1984 Oct;44(10):4642–4647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruoslahti E. Structure and biology of proteoglycans. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1988;4:229–255. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.001305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruoslahti E., Yamaguchi Y. Proteoglycans as modulators of growth factor activities. Cell. 1991 Mar 8;64(5):867–869. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90308-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steck P. A., Moser R. P., Bruner J. M., Liang L., Freidman A. N., Hwang T. L., Yung W. K. Altered expression and distribution of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in human gliomas. Cancer Res. 1989 Apr 15;49(8):2096–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timar J., Paterson H. Localization and production of proteoglycans by HT1080 cell lines with altered N-ras expression. Cancer Lett. 1990 Sep;53(2-3):145–150. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(90)90207-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timár J., Kovalszky I., Paku S., Lapis K., Kopper L. Two human melanoma xenografts with different metastatic capacity and glycosaminoglycan pattern. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1989;115(6):554–557. doi: 10.1007/BF00391357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underhill C. B., Keller J. M. Heparan sulfates of mouse cells. Analysis of parent and transformed 3T3 cell lines. J Cell Physiol. 1977 Jan;90(1):53–59. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040900108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasteson A. A method for the determination of the molecular weight and molecular-weight distribution of chondroitin sulphate. J Chromatogr. 1971 Jul 8;59(1):87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)80009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winterbourne D. J., Mora P. T. Altered metabolism of heparan sulfate in simian virus 40 transformed cloned mouse cells. J Biol Chem. 1978 Jul 25;253(14):5109–5120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y., Ruoslahti E. Expression of human proteoglycan in Chinese hamster ovary cells inhibits cell proliferation. Nature. 1988 Nov 17;336(6196):244–246. doi: 10.1038/336244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yayon A., Klagsbrun M., Esko J. D., Leder P., Ornitz D. M. Cell surface, heparin-like molecules are required for binding of basic fibroblast growth factor to its high affinity receptor. Cell. 1991 Feb 22;64(4):841–848. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90512-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries J. E., Keizer G. D., te Velde A. A., Voordouw A., Ruiter D., Rümke P., Spits H., Figdor C. G. Characterization of melanoma-associated surface antigens involved in the adhesion and motility of human melanoma cells. Int J Cancer. 1986 Oct 15;38(4):465–473. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910380403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]