Abstract

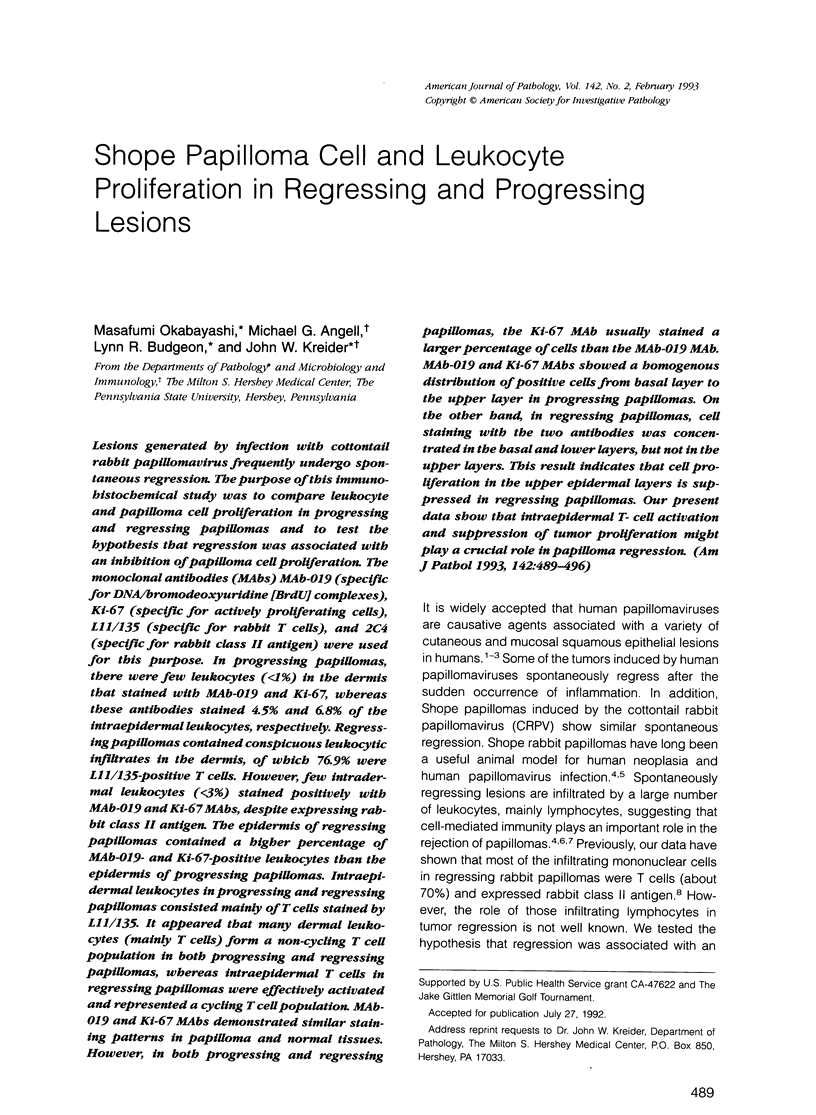

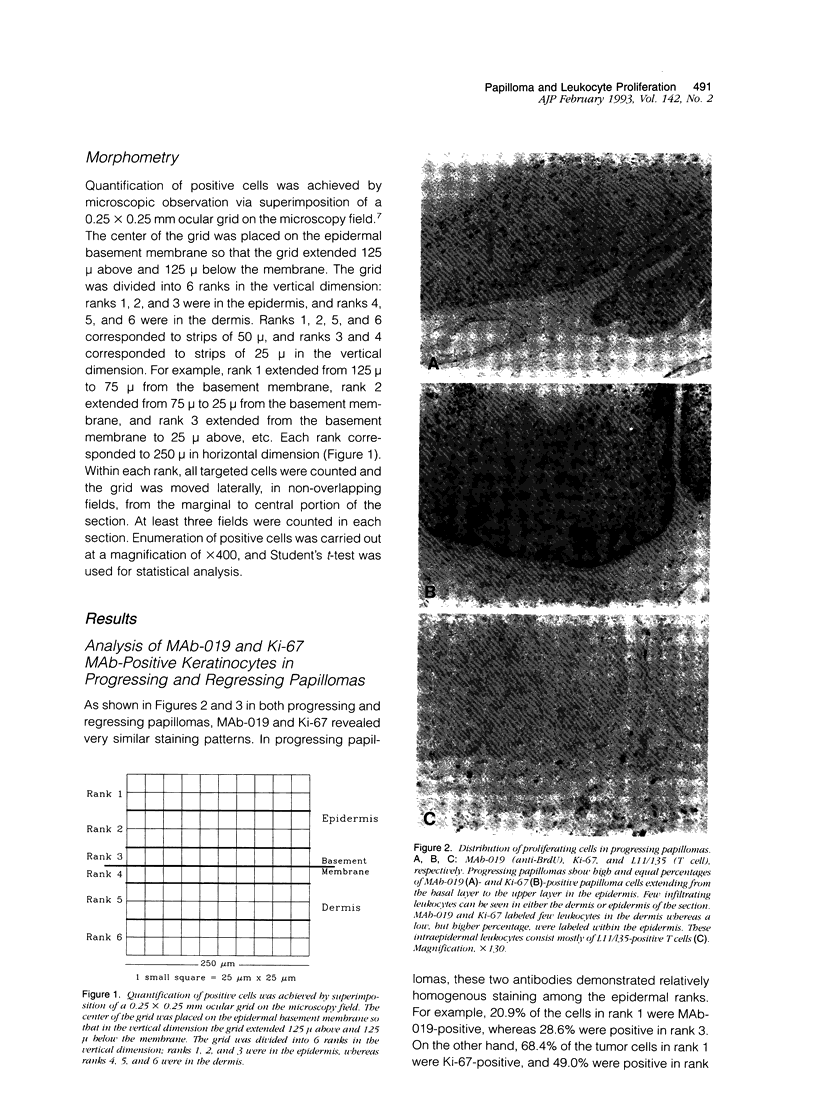

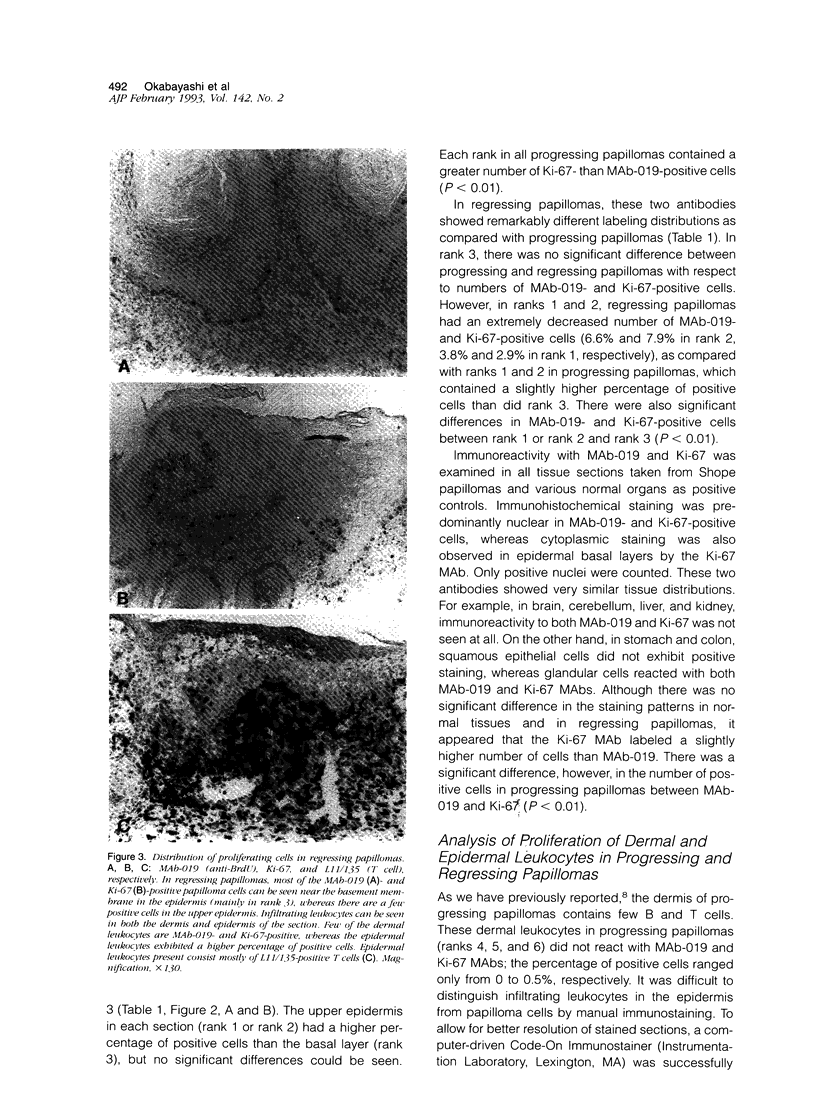

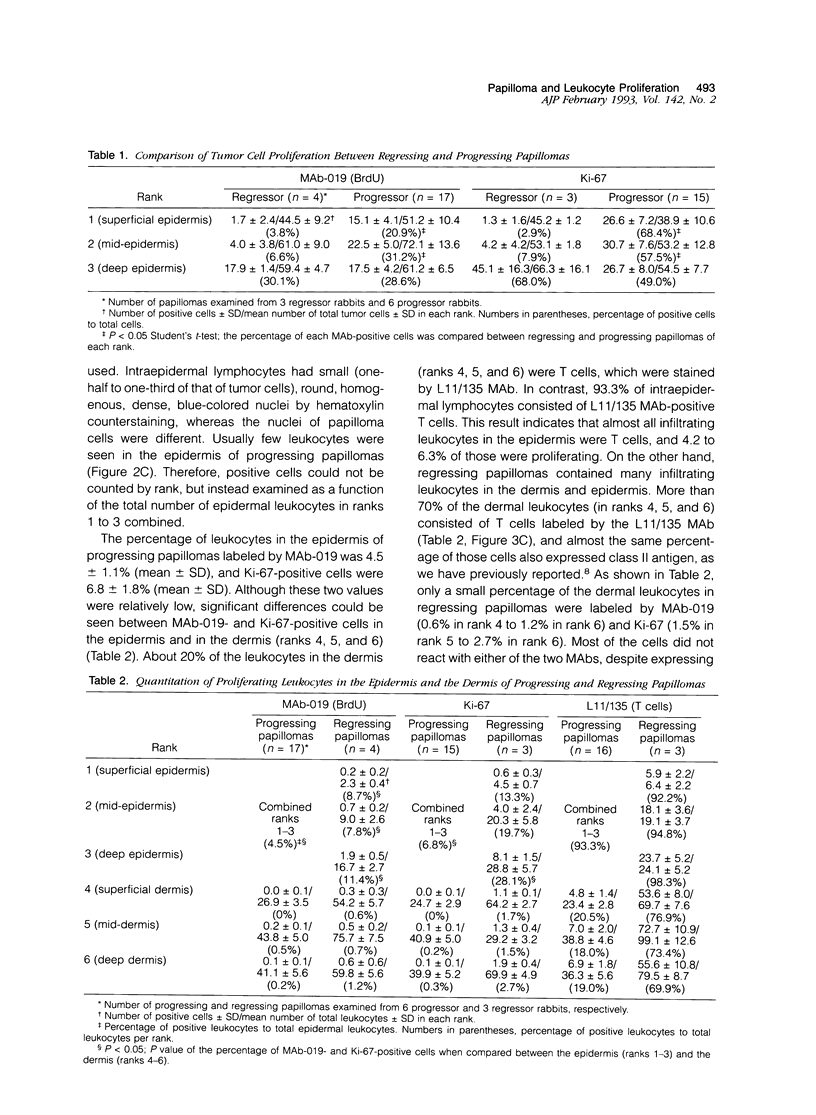

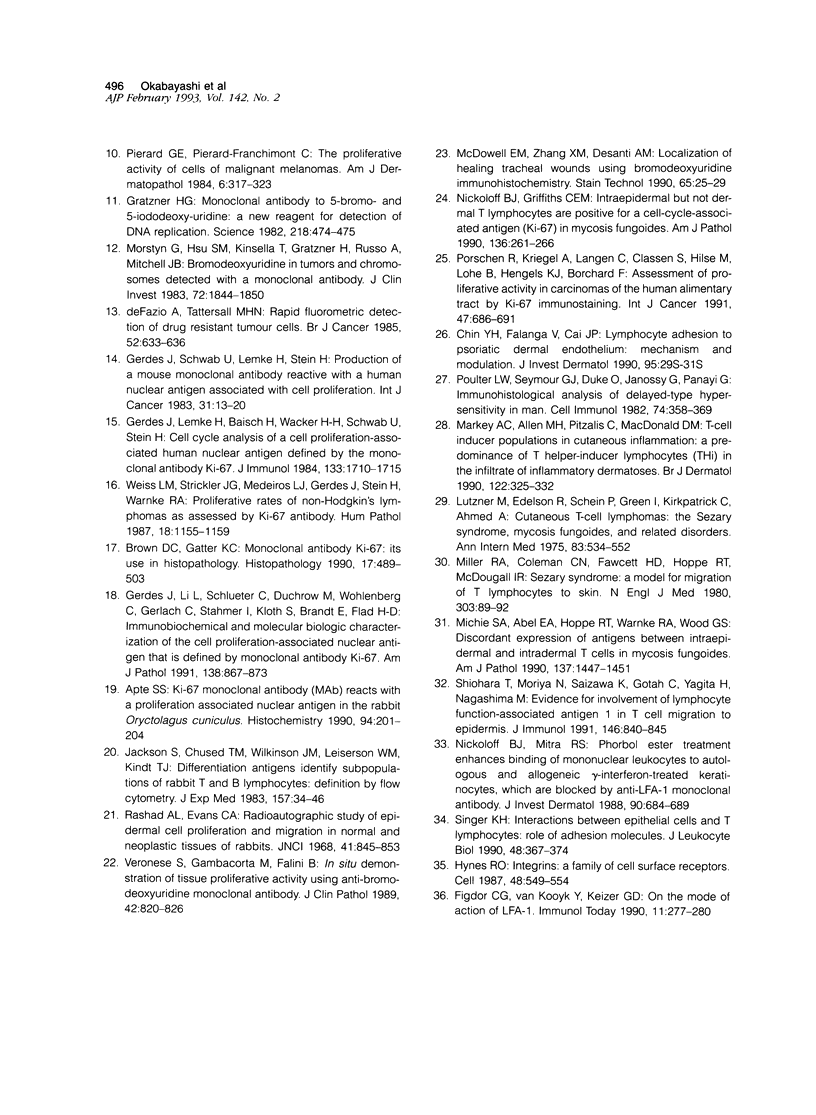

Lesions generated by infection with cottontail rabbit papillomavirus frequently undergo spontaneous regression. The purpose of this immunohistochemical study was to compare leukocyte and papilloma cell proliferation in progressing and regressing papillomas and to test the hypothesis that regression was associated with an inhibition of papilloma cell proliferation. The monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) MAb-019 (specific for DNA/bromodeoxyuridine [BrdU] complexes), Ki-67 (specific for actively proliferating cells), L11/135 (specific for rabbit T cells), and 2C4 (specific for rabbit class II antigen) were used for this purpose. In progressing papillomas, there were few leukocytes (< 1%) in the dermis that stained with MAb-019 and Ki-67, whereas these antibodies stained 4.5% and 6.8% of the intraepidermal leukocytes, respectively. Regressing papillomas contained conspicuous leukocytic infiltrates in the dermis, of which 76.9% were L11/135-positive T cells. However, few intradermal leukocytes (< 3%) stained positively with MAb-019 and Ki-67 MAbs, despite expressing rabbit class II antigen. The epidermis of regressing papillomas contained a higher percentage of MAb-019- and Ki-67-positive leukocytes than the epidermis of progressing papillomas. Intraepidermal leukocytes in progressing and regressing papillomas consisted mainly of T cells stained by L11/135. It appeared that many dermal leukocytes (mainly T cells) form a non-cycling T cell population in both progressing and regressing papillomas, whereas intraepidermal T cells in regressing papillomas were effectively activated and represented a cycling T cell population. MAb-019 and Ki-67 MAbs demonstrated similar staining patterns in papilloma and normal tissues. However, in both progressing and regressing papillomas, the Ki-67 MAb usually stained a larger percentage of cells than the MAb-019 MAb. MAb-019 and Ki-67 MAbs showed a homogeneous distribution of positive cells from basal layer to the upper layer in progressing papillomas. On the other hand, in regressing papillomas, cell staining with the two antibodies was concentrated in the basal and lower layers, but not in the upper layers. This result indicates that cell proliferation in the upper epidermal layers is suppressed in regressing papillomas. Our present data show that intraepidermal T- cell activation and suppression of tumor proliferation might play a crucial role in papilloma regression.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Apte S. S. Ki-67 monoclonal antibody (MAb) reacts with a proliferation associated nuclear antigen in the rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus. Histochemistry. 1990;94(2):201–204. doi: 10.1007/BF02440188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. C., Gatter K. C. Monoclonal antibody Ki-67: its use in histopathology. Histopathology. 1990 Dec;17(6):489–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1990.tb00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin Y. H., Falanga V., Cai J. P. Lymphocyte adhesion to psoriatic dermal endothelium: mechanism and modulation. J Invest Dermatol. 1990 Nov;95(5 Suppl):29S–31S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12505709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C. A., Ito Y. Antitumor immunity in the Shope papilloma-carcinoma complex of rabbits. 3. Response to reinfection with viral nucleic acid. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1966 Jun;36(6):1161–1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figdor C. G., van Kooyk Y., Keizer G. D. On the mode of action of LFA-1. Immunol Today. 1990 Aug;11(8):277–280. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90112-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes J., Lemke H., Baisch H., Wacker H. H., Schwab U., Stein H. Cell cycle analysis of a cell proliferation-associated human nuclear antigen defined by the monoclonal antibody Ki-67. J Immunol. 1984 Oct;133(4):1710–1715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes J., Li L., Schlueter C., Duchrow M., Wohlenberg C., Gerlach C., Stahmer I., Kloth S., Brandt E., Flad H. D. Immunobiochemical and molecular biologic characterization of the cell proliferation-associated nuclear antigen that is defined by monoclonal antibody Ki-67. Am J Pathol. 1991 Apr;138(4):867–873. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes J., Schwab U., Lemke H., Stein H. Production of a mouse monoclonal antibody reactive with a human nuclear antigen associated with cell proliferation. Int J Cancer. 1983 Jan 15;31(1):13–20. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910310104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratzner H. G. Monoclonal antibody to 5-bromo- and 5-iododeoxyuridine: A new reagent for detection of DNA replication. Science. 1982 Oct 29;218(4571):474–475. doi: 10.1126/science.7123245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes R. O. Integrins: a family of cell surface receptors. Cell. 1987 Feb 27;48(4):549–554. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson S., Chused T. M., Wilkinson J. M., Leiserson W. M., Kindt T. J. Differentiation antigens identify subpopulations of rabbit T and B lymphocytes. Definition by flow cytometry. J Exp Med. 1983 Jan 1;157(1):34–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEMBER N. F. Cell division in endochondral ossification. A study of cell proliferation in rat bones by the method of tritiated thymidine autoradiography. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1960 Nov;42B:824–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KREIDER J. W. STUDIES ON THE MECHANISM RESPONSIBLE FOR THE SPONTANEOUS REGRESSION OF THE SHOPE RABBIT PAPILLOMA. Cancer Res. 1963 Oct;23:1593–1599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider J. W., Howett M. K., Wolfe S. A., Bartlett G. L., Zaino R. J., Sedlacek T., Mortel R. Morphological transformation in vivo of human uterine cervix with papillomavirus from condylomata acuminata. Nature. 1985 Oct 17;317(6038):639–641. doi: 10.1038/317639a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzner M., Edelson R., Schein P., Green I., Kirkpatrick C., Ahmed A. Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: the Sézary syndrome, mycosis fungoides, and related disorders. Ann Intern Med. 1975 Oct;83(4):534–552. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-83-4-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markey A. C., Allen M. H., Pitzalis C., MacDonald D. M. T-cell inducer populations in cutaneous inflammation: a predominance of T helper-inducer lymphocytes (THi) in the infiltrate of inflammatory dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 1990 Mar;122(3):325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb08280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell E. M., Zhang X. M., DeSanti A. M. Localization of healing tracheal wounds using bromodeoxyuridine immunohistochemistry. Stain Technol. 1990;65(1):25–29. doi: 10.3109/10520299009105604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S. A., Abel E. A., Hoppe R. T., Warnke R. A., Wood G. S. Discordant expression of antigens between intraepidermal and intradermal T cells in mycosis fungoides. Am J Pathol. 1990 Dec;137(6):1447–1451. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. A., Coleman C. N., Fawcett H. D., Hoppe R. T., McDougall I. R. Sézary syndrome: a model for migration of T lymphocytes to skin. N Engl J Med. 1980 Jul 10;303(2):89–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198007103030206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morstyn G., Hsu S. M., Kinsella T., Gratzner H., Russo A., Mitchell J. B. Bromodeoxyuridine in tumors and chromosomes detected with a monoclonal antibody. J Clin Invest. 1983 Nov;72(5):1844–1850. doi: 10.1172/JCI111145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickoloff B. J., Griffiths C. E. Intraepidermal but not dermal T lymphocytes are positive for a cell-cycle-associated antigen (Ki-67) in mycosis fungoides. Am J Pathol. 1990 Feb;136(2):261–266. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickoloff B. J., Mitra R. S. Phorbol ester treatment enhances binding of mononuclear leukocytes to autologous and allogeneic gamma-interferon-treated keratinocytes, which are blocked by anti-LFA-1 monoclonal antibody. J Invest Dermatol. 1988 May;90(5):684–689. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12560903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okabayashi M., Angell M. G., Christensen N. D., Kreider J. W. Morphometric analysis and identification of infiltrating leucocytes in regressing and progressing Shope rabbit papillomas. Int J Cancer. 1991 Dec 2;49(6):919–923. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910490620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierard G. E., Pierard-Franchimont C. The proliferative activity of cells of malignant melanomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 1984 Summer;6 (Suppl):317–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porschen R., Kriegel A., Langen C., Classen S., Hilse M., Lohe B., Hengels K. J., Borchard F. Assessment of proliferative activity in carcinomas of the human alimentary tract by Ki-67 immunostaining. Int J Cancer. 1991 Mar 12;47(5):686–691. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910470510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulter L. W., Seymour G. J., Duke O., Janossy G., Panayi G. Immunohistological analysis of delayed-type hypersensitivity in man. Cell Immunol. 1982 Dec;74(2):358–369. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(82)90036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashad A. L., Evans C. A. Radioautographic study of epidermal cell proliferation and migration in normal and neoplastic tissues of rabbits. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1968 Oct;41(4):845–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiohara T., Moriya N., Saizawa K., Gotoh C., Yagita H., Nagashima M. Evidence for involvement of lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 in T cell migration to epidermis. J Immunol. 1991 Feb 1;146(3):840–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer K. H. Interactions between epithelial cells and T lymphocytes: role of adhesion molecules. J Leukoc Biol. 1990 Oct;48(4):367–374. doi: 10.1002/jlb.48.4.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagami H., Ogino A., Takigawa M., Imamura S., Ofuji S. Regression of plane warts following spontaneous inflammation. An histopathological study. Br J Dermatol. 1974 Feb;90(2):147–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1974.tb06378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veronese S., Gambacorta M., Falini B. In situ demonstration of tissue proliferative activity using anti-bromo-deoxyuridine monoclonal antibody. J Clin Pathol. 1989 Aug;42(8):820–826. doi: 10.1136/jcp.42.8.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss L. M., Strickler J. G., Medeiros L. J., Gerdes J., Stein H., Warnke R. A. Proliferative rates of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas as assessed by Ki-67 antibody. Hum Pathol. 1987 Nov;18(11):1155–1159. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(87)80384-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasumoto S., Burkhardt A. L., Doniger J., DiPaolo J. A. Human papillomavirus type 16 DNA-induced malignant transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. J Virol. 1986 Feb;57(2):572–577. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.2.572-577.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deFazio A., Tattersall M. H. Rapid fluorometric detection of drug resistant tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 1985 Oct;52(4):633–636. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1985.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- zur Hausen H. Human papillomaviruses and their possible role in squamous cell carcinomas. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1977;78:1–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-66800-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]