Abstract

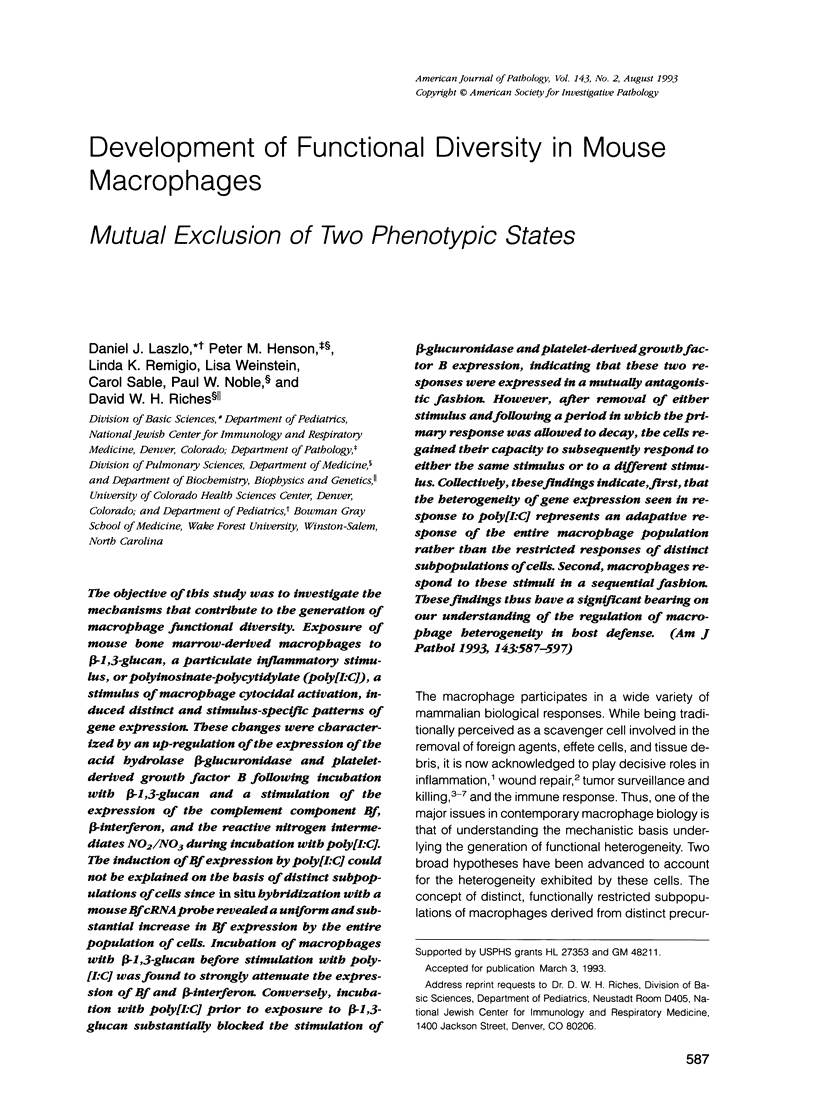

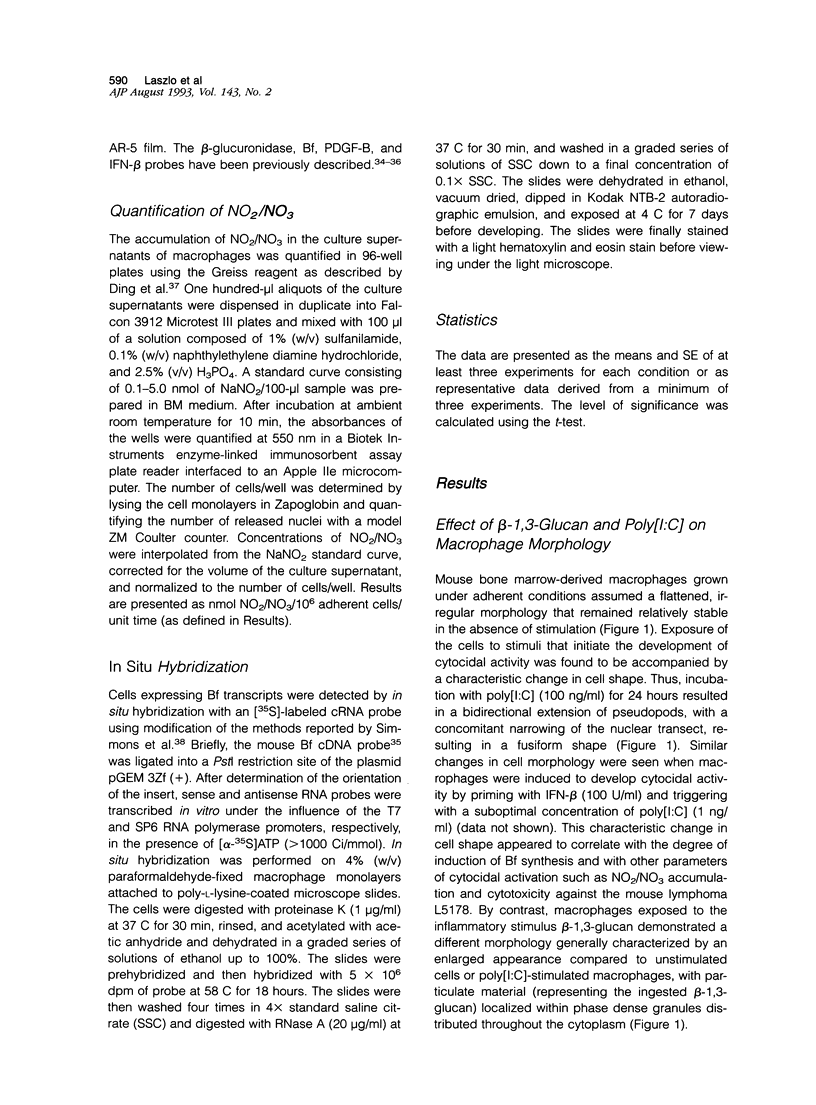

The objective of this study was to investigate the mechanisms that contribute to the generation of macrophage functional diversity. Exposure of mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages to beta-1,3-glucan, a particulate inflammatory stimulus, or polyinosinate-polycytidylate (poly[I:C]), a stimulus of macrophage cytocidal activation, induced distinct and stimulus-specific patterns of gene expression. These changes were characterized by an up-regulation of the expression of the acid hydrolase beta-glucuronidase and platelet-derived growth factor B following incubation with beta-1,3-glucan and a stimulation of the expression of the complement component Bf, beta-interferon, and the reactive nitrogen intermediates NO2/NO3 during incubation with poly[I:C]. The induction of Bf expression by poly[I:C] could not be explained on the basis of distinct subpopulations of cells since in situ hybridization with a mouse Bf cRNA probe revealed a uniform and substantial increase in Bf expression by the entire population of cells. Incubation of macrophages with beta-1,3-glucan before stimulation with poly[I:C] was found to strongly attenuate the expression of Bf and beta-interferon. Conversely, incubation with poly[I:C] prior to exposure to beta-1,3-glucan substantially blocked the stimulation of beta-glucuronidase and platelet-derived growth factor B expression, indicating that these two responses were expressed in a mutually antagonistic fashion. However, after removal of either stimulus and following a period in which the primary response was allowed to decay, the cells regained their capacity to subsequently respond to either the same stimulus or to a different stimulus. Collectively, these findings indicate, first, that the heterogeneity of gene expression seen in response to poly[I:C] represents an adaptive response of the entire macrophage population rather than the restricted responses of distinct subpopulations of cells. Second, macrophages respond to these stimuli in a sequential fashion. These findings thus have a significant bearing on our understanding of the regulation of macrophage heterogeneity in host defense.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alexander P., Evans R. Endotoxin and double stranded RNA render macrophages cytotoxic. Nat New Biol. 1971 Jul 21;232(29):76–78. doi: 10.1038/newbio232076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axline S. G., Cohn Z. A. In vitro induction of lysosomal enzymes by phagocytosis. J Exp Med. 1970 Jun 1;131(6):1239–1260. doi: 10.1084/jem.131.6.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursuker I., Goldman R. On the origin of macrophage heterogeneity: a hypothesis. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1983 Mar;33(3):207–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursuker I., Goldman R., Schade U., Lohmann-Matthes M. L. Differences in antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against tumor cells in in vitro differentiating mononuclear phagocytes from bone marrows of normal and inflamed mice. Cell Immunol. 1982 Mar 15;68(1):53–63. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(82)90089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHN Z. A., BENSON B. THE DIFFERENTIATION OF MONONUCLEAR PHAGOCYTES. MORPHOLOGY, CYTOCHEMISTRY, AND BIOCHEMISTRY. J Exp Med. 1965 Jan 1;121:153–170. doi: 10.1084/jem.121.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall J. F., Leary S. L. Detection of early changes in androgen-induced mouse renal beta-glucuronidase messenger ribonucleic acid using cloned complementary deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1983 Dec 20;22(26):6049–6053. doi: 10.1021/bi00295a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirgwin J. M., Przybyla A. E., MacDonald R. J., Rutter W. J. Isolation of biologically active ribonucleic acid from sources enriched in ribonuclease. Biochemistry. 1979 Nov 27;18(24):5294–5299. doi: 10.1021/bi00591a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole F. S., Auerbach H. S., Goldberger G., Colten H. R. Tissue-specific pretranslational regulation of complement production in human mononuclear phagocytes. J Immunol. 1985 Apr;134(4):2610–2616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Whalley C. V., Riches D. W. Influence of the cytocidal macrophage phenotype on the degradation of acetylated low density lipoproteins: dual regulation of scavenger receptor activity and of intracellular degradation of endocytosed ligand. Exp Cell Res. 1991 Feb;192(2):460–468. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deimann W., Fahimi H. D. Hepatic granulomas induced by glucan. An ultrastructural and peroxidase-cytochemical study. Lab Invest. 1980 Aug;43(2):172–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding A. H., Nathan C. F., Stuehr D. J. Release of reactive nitrogen intermediates and reactive oxygen intermediates from mouse peritoneal macrophages. Comparison of activating cytokines and evidence for independent production. J Immunol. 1988 Oct 1;141(7):2407–2412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R., Alexander P. Cooperation of immune lymphoid cells with macrophages in tumour immunity. Nature. 1970 Nov 14;228(5272):620–622. doi: 10.1038/228620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R., Eidlen L. G. The role of the inflammatory response during tumor growth. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1982;155:379–387. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4394-3_39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk L. A., Hogan M. M., Vogel S. N. Bone marrow progenitors cultured in the presence of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor versus macrophage colony-stimulating factor differentiate into macrophages with distinct tumoricidal capacities. J Leukoc Biol. 1988 May;43(5):471–476. doi: 10.1002/jlb.43.5.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerstrøm J., Unsgaard G. In vitro influence of endotoxin on human mononuclear phagocyte structure and function. 1. Depression of protein synthesis, phagocytosis of Candida albicans and induction of cytostatic activity. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand C. 1979 Dec;87(6):381–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heremans H., Dijkmans R., Sobis H., Vandekerckhove F., Billiau A. Regulation by interferons of the local inflammatory response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1987 Jun 15;138(12):4175–4179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs J. B., Jr, Lambert L. H., Jr, Remington J. S. Control of carcinogenesis: a possible role for the activated macrophage. Science. 1972 Sep 15;177(4053):998–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4053.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs J. B., Jr, Taintor R. R., Vavrin Z. Macrophage cytotoxicity: role for L-arginine deiminase and imino nitrogen oxidation to nitrite. Science. 1987 Jan 23;235(4787):473–476. doi: 10.1126/science.2432665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi Y., Sokawa Y., Watanabe Y., Kawade Y., Ohno S., Takaoka C., Taniguchi T. Structure and expression of a cloned cDNA for mouse interferon-beta. J Biol Chem. 1983 Aug 10;258(15):9522–9529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imber M. J., Pizzo S. V., Johnson W. J., Adams D. O. Selective diminution of the binding of mannose by murine macrophages in the late stages of activation. J Biol Chem. 1982 May 10;257(9):5129–5135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikura H., Jayaraman S., Kuchroo V., Diamond B., Saito S., Dorf M. E. Functional analysis of cloned macrophage hybridomas. VII. Modulation of suppressor T cell-inducing activity. J Immunol. 1989 Jul 15;143(2):414–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keystone E. C., Schorlemmer H. U., Pope C., Allison A. C. Zymosan-induced arthritis: a model of chronic proliferative arthritis following activation of the alternative pathway of complement. Arthritis Rheum. 1977 Sep-Oct;20(7):1396–1401. doi: 10.1002/art.1780200714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibovich S. J., Ross R. The role of the macrophage in wound repair. A study with hydrocortisone and antimacrophage serum. Am J Pathol. 1975 Jan;78(1):71–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew D. B., Leslie C. C., Henson P. M., Riches D. W. Role of endogenously derived leukotrienes in the regulation of lysosomal enzyme expression in macrophages exposed to beta 1,3-glucan. J Leukoc Biol. 1991 Mar;49(3):266–276. doi: 10.1002/jlb.49.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew D. B., Leslie C. C., Riches D. W., Henson P. M. Induction of macrophage lysosomal hydrolase synthesis and secretion by beta-1,3-glucan. Cell Immunol. 1986 Jul;100(2):340–350. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(86)90034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. N., Uchida T., Ju S. T., Dorf M. E. Functional analysis of macrophage hybridomas. II. Antibody-independent tumor cytotoxicity and its dissociation from IL-1 production and Ia expression. Cell Immunol. 1985 Apr 15;92(1):142–153. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(85)90072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister H., Heymer B., Schäfer H., Haferkamp O. Role of Candida albicans in granulomatous tissue reactions. II. In vivo degradation of C. albicans in hepatic macrophages of mice. J Infect Dis. 1977 Feb;135(2):235–242. doi: 10.1093/infdis/135.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riches D. W., Henson P. M. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide suppresses the production of catalytically active lysosomal acid hydrolases in human macrophages. J Cell Biol. 1986 May;102(5):1606–1614. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.5.1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riches D. W., Henson P. M., Remigio L. K., Catterall J. F., Strunk R. C. Differential regulation of gene expression during macrophage activation with a polyribonucleotide. The role of endogenously derived IFN. J Immunol. 1988 Jul 1;141(1):180–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riches D. W., Underwood G. A. Expression of interferon-beta during the triggering phase of macrophage cytocidal activation. Evidence for an autocrine/paracrine role in the regulation of this state. J Biol Chem. 1991 Dec 25;266(36):24785–24792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts B. E., Paterson B. M. Efficient translation of tobacco mosaic virus RNA and rabbit globin 9S RNA in a cell-free system from commercial wheat germ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973 Aug;70(8):2330–2334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.8.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruco L. P., Meltzer M. S. Macrophage activation for tumor cytotoxicity: development of macrophage cytotoxic activity requires completion of a sequence of short-lived intermediary reactions. J Immunol. 1978 Nov;121(5):2035–2042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell S. W., Doe W. F., McIntosh A. T. Functional characterization of a stable, noncytolytic stage of macrophage activation in tumors. J Exp Med. 1977 Dec 1;146(6):1511–1520. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.6.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackstein R., Colten H. R., Woods D. E. Phylogenetic conservation of a class III major histocompatibility complex antigen, factor B. Isolation and nucleotide sequencing of mouse factor B cDNA clones. J Biol Chem. 1983 Dec 10;258(23):14693–14697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorlemmer H. U., Davies P., Hylton W., Gugig M., Allison A. C. The selective release of lysosomal acid hydrolases from mouse peritoneal macrophages by stimuli of chronic inflammation. Br J Exp Pathol. 1977 Jun;58(3):315–326. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuehr D. J., Marletta M. A. Mammalian nitrate biosynthesis: mouse macrophages produce nitrite and nitrate in response to Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Nov;82(22):7738–7742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.22.7738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga M., Dannenberg A. M., Jr, Higuchi S. Macrophage functional heterogeneity in vivo. Macrolocal and microlocal macrophage activation, identified by double-staining tissue sections of BCG granulomas for pairs of enzymes. Am J Pathol. 1980 May;99(2):305–323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto M., Dannenberg A. M., Jr, Wahl L. M., Ettinger W. H., Jr, Hastie A. T., Daniels D. C., Thomas C. R., Demoulin-Brahy L. Extracellular hydrolytic enzymes of rabbit dermal tuberculous lesions and tuberculin reactions collected in skin chambers. Am J Pathol. 1978 Mar;90(3):583–607. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T., Ju S., Fay A., Liu Y., Dorf M. E. Functional analysis of macrophage hybridomas. I. Production and initial characterization. J Immunol. 1985 Feb;134(2):772–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsgaard G. Cytostatic and phagocytic capacity of lymphokine-activated human monocytes. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand C. 1979 Oct;87(5):325–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl S. M., Allen J. B., Ohura K., Chenoweth D. E., Hand A. R. IFN-gamma inhibits inflammatory cell recruitment and the evolution of bacterial cell wall-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 1991 Jan 1;146(1):95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werb Z., Chin J. R. Endotoxin suppresses expression of apoprotein E by mouse macrophages in vivo and in culture. A biochemical and genetic study. J Biol Chem. 1983 Sep 10;258(17):10642–10648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]