Abstract

In cerebellum and other brain regions, neuronal cell death because of ethanol consumption by the mother is thought to be the leading cause of neurological deficits in the offspring. However, little is known about how surviving cells function. We studied cerebellar Purkinje cells in vivo and in vitro to determine whether function of these cells was altered after prenatal ethanol exposure. We observed that Purkinje cells that were prenatally exposed to ethanol presented decreased voltage-gated calcium currents because of a decreased expression of the γ-isoform of protein kinase C. Long-term depression at the parallel fiber–Purkinje cell synapse in the cerebellum was converted into long-term potentiation. This likely explains the dramatic increase in Purkinje cell firing and the rapid oscillations of local field potential observed in alert fetal alcohol syndrome mice. Our data strongly suggest that reversal of long-term synaptic plasticity and increased firing rates of Purkinje cells in vivo are major contributors to the ataxia and motor learning deficits observed in fetal alcohol syndrome. Our results show that calcium-related neuronal dysfunction is central to the pathogenesis of the neurological manifestations of fetal alcohol syndrome and suggest new methods for treatment of this disorder.

Keywords: calcium, cerebellum, protein kinase, long-term depression, motor learning

Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) is the leading cause of intellectual disability in the Western world with a prevalence of 1 to 1.5 cases per 1,000 live births (1) and a lifetime cost of care of approximately $1.4 million per case. This cost is mainly because of ethanol toxicity in the developing central nervous system, causing intellectual disability, deficits in learning, and fine-motor dysfunction (2).

The cerebellum is one of the main targets of in utero ethanol toxicity (3). Within the cerebellum, Purkinje cells (PCs) are highly sensitive to ethanol. PCs constitute the sole output of the cerebellar cortex and thus have a central functional role in integration. All animal models of FAS display a reduction in the number of PCs by ≈20% (4), and various authors have proposed that neuronal loss is the only cause of cerebellar deficits in FAS. One study conducted on adult anesthetized rats with FAS led to the conclusion that PCs that survive ethanol administration function normally (5). Thomas et al. (6) found a correlation between total PCs number and motor performance. These experimental data led to the assumption that surviving PCs function normally and that motor coordination impairment in FAS results only from a quantitative defect of PCs. This is crucially important from a therapeutic point of view because very few options exist to replace dead neurons. Many studies have therefore focused on different ways to decrease PC loss in FAS (7, 8). However, different models of ataxia that result from PC death per se (pcd mice, SV4 mice, T147 transgenic mice) have demonstrated that considerable neuropathology can occur without the manifestation of a neurological phenotype and that ataxia occurs in mice only after there is loss of 50–75% of the PCs (9–11). Because FAS models are characterized by a nonprogressive loss of only 20% of PCs, the presence of an associated neuronal dysfunction can contribute to the observed ataxic phenotype. Because the understanding of the relative contribution of neuronal dysfunction and cell death to neurological deficits occurring in FAS is central for the evaluation of potential prevention or therapeutics, we looked for a neuronal dysfunction of surviving PCs by using combined in vivo and in vitro recordings in a mouse model of this condition.

Results

Histological and Behavioral Alterations in the Mouse Model of FAS.

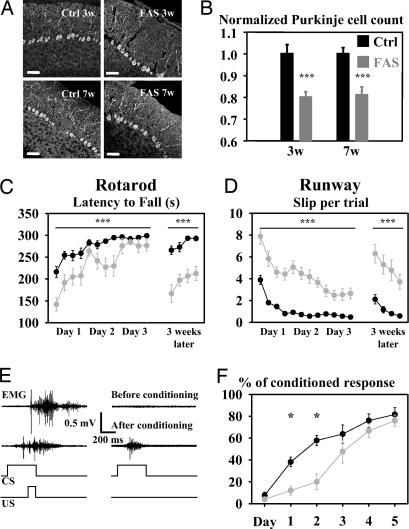

A 20% loss of PCs was observed in 3- or 7-week-old FAS mice when compared with corresponding control groups (P < 0.001, Fig. 1 A and B). This reduction was similar at 3 and 7 weeks (P > 0.05, Fig. 1B). FAS mice demonstrated significant impairment in motor coordination in both rotarod and runway assays (P < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA for repeated measures (Fig. 1 C and D, days 1–3). Eyelid conditioning, a much more cerebellar specific task, was studied in 10 FAS and 10 control mice. Comparison of the daily percentage of conditioned response during eyelid conditioning demonstrated a significant difference in motor learning between FAS and control mice (P = 0.013, two-way ANOVA for repeated measures) (Fig. 1 E and F). Mortality and ethanol levels in FAS mice are available in supporting information (SI) Materials and Methods.

Fig. 1.

Mice prenatally exposed to ethanol display a nonprogressive PC loss, ataxia, and deficits in motor learning. (A) Double calbindin (green)/TOTO (red) staining of lobule X in FAS (Right) and control (Left) mice aged 3 (Upper) or 7 weeks (Lower). (Scale bars, 50 μm.) (B) PC count in control and FAS mice aged 3 and 7 weeks. Values were normalized to the average PC count in the corresponding control group. (C) Latency to fall off the rotarod during the learning session (days 1–3) and after a 3-week test-free period. (D) Number of slips from the runway bar. (E) EMG recording from the orbicularis oculi in a control mouse during associated unconditioned stimulus (US) and conditioned stimulus (CS) (Left) and during the CS alone (Right) before (upper traces) and after (lower traces) conditioning. (F) Plotted daily values of conditioned response percentage after CS alone in FAS and control mice during conditioning. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001).

FAS PCs Had Increased Simple Spike Firing, Supporting Fast Oscillations in Vivo.

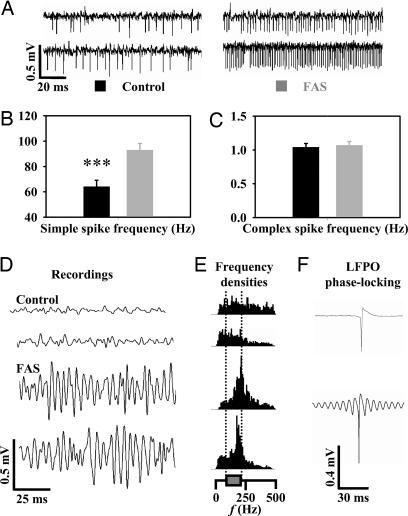

PC firing regulation is crucial in motor coordination. Thus, we studied the spontaneous PC firing in seven FAS and five control alert mice. A total of 66 PCs were recorded (42 in FAS and 24 in control mice). PCs from FAS mice had an increased simple spike firing rate (Fig. 2 A and B). In contrast, the complex spike firing rate was normal in FAS mice (Fig. 2C), demonstrating that decreased firing of inferior olivary neurons was not responsible for the increased PC simple spike firing rate. During ≈30% of the recording time in FAS mice, a fast local field potential oscillation (LFPO) was noticed (LFPO index = 5.8 ± 2.4; frequency = 196 ± 37 Hz; Fig. 2 D and E, lower traces). In contrast, no LFPO was recorded in controls (Fig. 2 D and E, upper traces). As observed in other mouse models presenting fast LFPO, 11 FAS PCs recorded during these fast oscillation episodes demonstrated a tight phase-locking with the oscillation, as illustrated by the wave trigger averaged traces of simple spikes (Fig. 2F, lower trace), whereas similar averaging in control mice never elicited similar tight phase-locking with oscillation (Fig. 2F, upper trace).

Fig. 2.

In vivo PC firing is increased in FAS. (A) Extracellular recordings of three PCs in alert control (left traces) and FAS mice (right traces). Histogram values of mean simple spike firing rate (B) and complex spike frequency (C) in FAS and control cells. (D) Local field potential in control and FAS mice with corresponding Fourier spectrum (E). (F) Wave-triggered averaging of a simple spike recorded in a control (upper trace) and in a FAS mouse (lower trace) during an episode of fast oscillation.

PCs' Increased Activity in Alert FAS Mice Was Not Caused by Increased Intrinsic Excitability or Increased Excitatory Synaptic Strength.

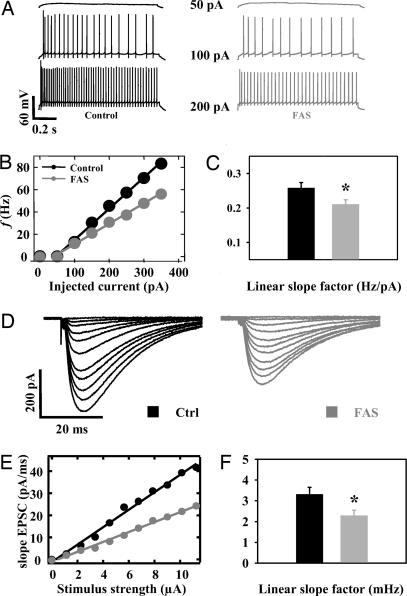

Increased firing rate of PCs in alert FAS mice could result from increased intrinsic PC excitability. Intrinsic excitability investigated by the slope of current–frequency plots (Fig. 3 B and C) obtained from increasing depolarizing current steps (Fig. 3A) was not increased in FAS PCs (n = 23) compared with control cells (n = 26; P < 0.05, Fig. 3 A–C). We then looked at the strength of excitatory synapses onto the PCs. The study of the relationship between increasing stimulation of parallel fibers and the initial slope of evoked post synaptic currents demonstrated that the strength of the parallel fiber–PC synapse was not increased in FAS (Fig. 3 D–F). The reduction of PF–PC excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) is partially caused by a presynaptic alteration as shown by paired-pulse facilitation recordings (SI Fig. 5 A and B). The study of the area under the all-or-none response evoked by stimulation of the climbing fiber demonstrated that the strength of the climbing fiber–PC synapse was not increased in FAS (SI Fig. 5 C and D).

Fig. 3.

In vivo PCs' hyperactivity is not caused by an increased intrinsic excitability or by an increased excitatory synaptic strength in FAS. (A) Firing activity of a control and a FAS PC elicited by steps of depolarizing currents from a −80 mV membrane potential. (B) Plotted values of mean PC firing rate as a function of injected current in FAS and in control cells. (C) Histogram values of mean linear slope in both groups. (D–F) Synaptic strength of the parallel fiber–PC synapse is decreased in FAS. (D) Typical input–output relationships obtained from PCs in response to an increasing stimulation of parallel fibers in a control (Left) and a FAS (Right) PC. Negative current pulses ranging from 0 to 11 μA were delivered in ascending order. (E) Linear relation between EPSC initial slope and stimulus intensity in the cells illustrated in D. (F) Histograms of slope coefficient values in FAS and in control mice.

The Parallel Fiber–PC Long-Term Depression (LTD) Was Shifted Toward a Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) in FAS.

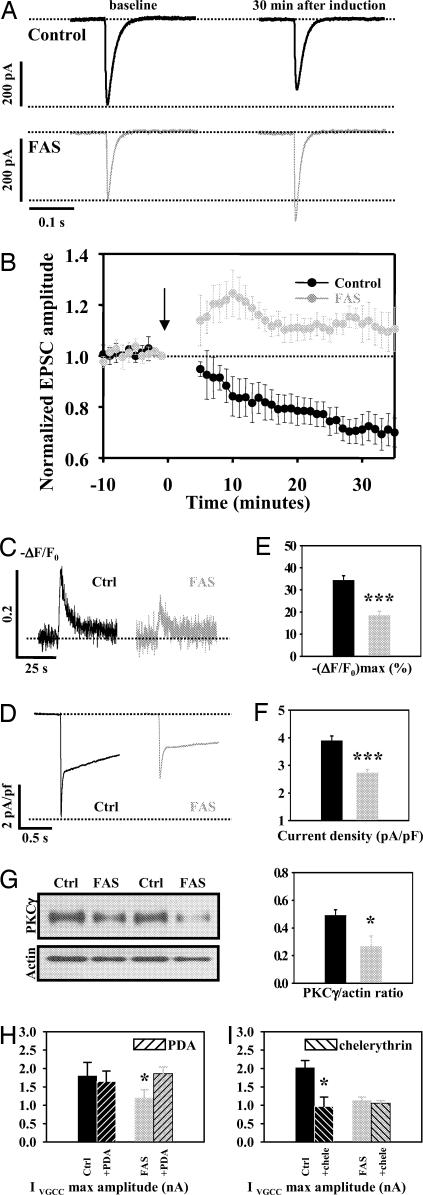

It has been proposed that cerebellar LTD controls PC firing (12, 13) and is central in eyelid conditioning (14, 15). Thus, we hypothesized that LTD could be altered in FAS mice. The induction of this LTD requires the pairing of parallel fiber stimulation to either a climbing fiber stimulation or a somatic depolarization of the PC, mimicking the climbing fiber stimulation by rising postsynaptic calcium concentration. When this latter protocol was applied to control cells (n = 6; Fig. 4A, upper traces), the mean maximal EPSC amplitude (normalized to amplitude at time 0) was significantly reduced 20–30 min after induction (75.1 ± 4.85%) compared with baseline (101.01 ± 1.76, P < 0.01, Fig. 4B), resulting in the LTD. The same protocol applied to FAS PCs (n = 5; Fig. 4A, lower traces) showed a sustained increased mean maximal EPSC amplitude 20–30 min after induction compared with baseline (111.87 ± 4.1% vs. 100.9 ± 1.83%, P < 0.05, paired t test, Fig. 4B), thus resulting in a LTP instead of the classically observed LTD. The difference between FAS and control cells assessed by a two-way ANOVA was highly significant (P < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

PCs of FAS mice present a shift of LTD toward LTP and a reduction of calcium currents caused by a decrease in expression of PKC. (A) Typical EPSC recorded in a control (Upper) and a FAS (Lower) PC before (left) and after (right) the LTD induction protocol. (B) Plotted value of mean EPSC amplitude (normalized to EPSC value at t0) in FAS and in control cells before and after the LTD induction protocol (indicated by the arrow). (C) Typical calcium transient evoked by a 2-s depolarization from −60 to 0 mV in a control (Left) and a FAS PC (Right). (D) Typical voltage-gated calcium current evoked by a 1-s depolarization from −60 to 0 mV in a control PC (Left) and in a FAS PC (Right). (E) Depolarization-evoked calcium transients were significantly reduced in FAS. Histogram values of calcium transients normalized maximal amplitude. (F) Depolarization-evoked calcium currents were significantly reduced in FAS. Histogram values of calcium current density are shown. (G) The expression of membrane PKCγ was reduced within FAS cerebella compared with control ones. Representative Western blot analyses for PKCγ from cerebellar membrane extracts of control and FAS mice. Western blot analyses of actin are shown as a loading control. Histograms represent the corresponding densitometric analysis of pooled experiments made by using 10 different mice per group and normalization for the amount of protein loaded (in arbitrary units). (H) Effect of PKC activation by PDA 10 μM on the maximal amplitude of pharmacologically isolated voltage-gated calcium current (VGCC) in control (black) and FAS (gray) PCs. Shaded bars represent current amplitude after application of PDA. (I) Effect of PKC inhibition by chelerythrin 10 μM on the maximal amplitude of pharmacologically isolated VGCC in control (black) and FAS (gray) PCs. Shaded bars represent current amplitude after application of chelerythrin.

Calcium Entry into PCs Through High Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels Was Reduced in FAS.

Because the direction of long-term parallel fiber–PCs synapse is controlled by calcium entry (16), it was investigated by calcium imaging and measurement of voltage-gated calcium currents. Intracellular free-calcium level [Ca2+]i changes (−ΔF/F0) elicited by depolarizing PCs from −60 to 0 mV were significantly reduced in FAS PCs (n = 24) compared with control cells (n = 27) (P < 0.001, Fig. 4 C and E). Pharmacologically isolated calcium currents elicited by test pulses from −60 to 0 mV were significantly smaller in FAS PCs (n = 21) than in control cells (n = 28) (P < 0.001, Fig. 4 D and F).

The reduced voltage-dependent calcium current in FAS may result from alterations of channels expression or activation/inactivation kinetics. Inactivation time constants of high voltage-gated calcium currents calculated from monoexponential curves fit to the data in the first 200 ms after the peak current were similar in control (n = 37) and FAS (n = 21) PCs (P > 0.05, SI Fig. 6A). The expression of three distinct high voltage-activated calcium channels (VGCC) (Cav1.2 (L-type), Cav2.1 (P/Q-type), and Cav2.2 (N-type) channels) that are highly enriched in PCs (17, 18) was studied by Western blot analyses in membrane preparations from FAS and control mice cerebella (10 brains per group). The levels of Cav1.2, Cav2.1, and Cav2.2 did not differ significantly between FAS and control mice (SI Fig. 6 B–D). Given the dendritic localization of VGCC (19, 20) and the difficulties in clamping the extensive dendritic arborization of PCs in slices (20), we were not able to study directly the voltage-dependence of activation/inactivation of high voltage-gated calcium currents.

Reduced PKCγ Expression Causes Reduced Voltage-Gated Calcium Current in FAS.

Because the activation of VGCC relies on channels phosphorylation by PKC and because a decreased expression of PKC enzyme was observed in previous FAS models (21, 22), we studied the expression of the membrane-bound γ-isoform (PKCγ) that is highly expressed in PCs (23) by using Western blot analysis. We found that the normalized level of PKCγ was significantly reduced in FAS mice (n = 6) compared with control mice (n = 8, P < 0.05) (Fig. 4 G and H). We performed coimmunostaining for calbindin and PKCγ and confirmed that this isoform of PKC is expressed only within PCs in the cerebellum (SI Fig. 7) as described by Bareggi et al. (24). These stainings also suggest a reduction of the expression of PKCγ within FAS PCs and demonstrate that PKCγ expression studied by Western blot is specific for PCs.

We have then tested our hypothesis that the reduced voltage-dependent calcium current observed in FAS was caused by a reduced phosphorylation of the corresponding channels by PKC. We recorded pharmacologically isolated calcium currents elicited by test pulses from −60 to 0 mV. Then we applied the specific PKC activator phorbol 12, 13 diacetate (PDA, 10 μM) or the specific PKC inhibitor chelerythrin (10 μM) in the bath solution. We observed that PDA significantly increased the maximal amplitude of voltage-dependent calcium current recorded from FAS PCs (n = 7, paired t test P < 0.05) but not in control PCs (n = 7, P > 0.05) (Fig. 4H). On the other hand chelerythrin significantly decreased voltage-dependent calcium current recorded from control PCs (n = 5, P < 0.05) but not from FAS PCs (n = 8, P > 0.05) (Fig. 4H). These data show that PKC phosphorylation of voltage-dependent calcium channels has a functional impact on calcium current amplitude in normal conditions but not in FAS and that PKC activation allows to recover a normal calcium current amplitude in FAS.

Discussion

Our study shows in vitro and in vivo dysfunctions of PCs in an animal model of FAS that has not previously been demonstrated. The contribution of neuronal dysfunction to neurological deficits occurring in FAS is central for the evaluation of potential prevention or therapeutics. Combined recordings from brain slices and alert mice in this FAS model strongly suggest that behavioral abnormalities (motor incoordination and learning deficits) and PCs firing properties (higher simple spike frequency and fast oscillation) are supported by a reduction of depolarization-induced calcium currents in cerebellar PCs associated with a shift of the cerebellar long-term depression toward an atypical LTP.

This study demonstrates that surviving PCs from FAS mice exhibit a dramatic dysfunction. Indeed, the spontaneous PCs firing was increased in alert FAS mice when compared with control mice. In addition, we found that the cerebellar cortex from FAS mice present a fast LFPO, phase-locked with the rhythmic discharge of PCs. This pattern of increased spontaneous in vivo activity associated with a fast LFPO is similar to the one observed in different ataxic mutant mice (25–28). We have previously proposed that increased in vivo firing activity and associated fast cerebellar oscillations constitute a mechanism of cerebellar dysfunction leading to ataxia (26, 29). Our recordings from alert FAS and control mice are more reliable than the study of Backman et al. (5) showing no differences in spontaneous activity or firing patterns between control and anesthetized ethanol-exposed animals because anesthetics modify PC firing and disrupt LFPO (26, 30). The two studies also differ in ethanol exposition timing. In vivo recordings allowed us to reject the hypothesis that increased simple spike firing in FAS results from a decreased olivary activity (31) because the complex spike firing rate was not altered in FAS. We have then used slices recordings to exclude the possibility that increased simple spike firing in FAS was caused by an increased intrinsic excitability or by an increased synaptic strength of the two excitatory inputs of PCs: parallel and climbing fibers. EPSCs resulting from parallel fiber stimulation were reduced in FAS. We believe that a combination of pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms explains this result because it was demonstrated in the hippocampus where ethanol reduces postsynaptic AMPA currents and also acts at the presynaptic level (32). We also demonstrated a presynaptic alteration in our FAS model (SI Fig. 5 A and B).

LTD at the parallel fiber–PC synapse has been proposed as the mechanism that regulates PC firing in vivo (12, 13). We thus looked for an alteration of LTD in our model, and we demonstrated that the protocol that induces LTD in control mice evokes LTP in FAS mice. It can be argued that the abolition of LTD in PCs does not cause alteration in PC firing in vivo or motor coordination impairment (14). In the present FAS model, LTD was not only absent but replaced by LTP. Thus, we hypothesize that this shift results in a chronic overstimulation of PCs by the parallel fibers, resulting in increased PC firing in vivo. According to the view that an intact LTD at the parallel fiber–PC synapse is required for the optimal efficiency of eyelid conditioning studied as a prototypical reflect of cerebellar learning (15, 33), the shift of LTD toward LTP in FAS could also contribute to the deficits in eyelid conditioning and motor learning. Whether the replacement of LTD by LTP in FAS mice constitutes the only cause of LFPO emergence and PCs firing behavior in FAS has not yet been demonstrated, because other mechanisms that involve the PCs and/or other cerebellar neurons could also participate. For instance, the involvement of other cerebellar neurons, such as molecular layer interneurons, Golgi, or granule cells, and of their respective synaptic plasticity, was not studied here. Other cerebellar neurons, for instance granule cells, are known to be sensitive to ethanol (34). In addition, we did not rule out that increased simple spike firing in FAS could partially result from hyperexcitation of extracerebellar areas that project on the cerebellum.

Intracytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration controls the direction of long term synaptic plasticity at the parallel fiber–PC synapse (16). Indeed, concomitant stimulation of parallel and climbing fibers leads to a parallel fiber–PC LTD under standard conditions and LTP when calcium buffering lowers intracytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration. Thus, we reasoned that LTD could be altered in the present FAS model if calcium entry were reduced. Indeed, we demonstrated a reduction of voltage-gated calcium currents and of calcium entry after depolarization, as observed in whole-brain dissociated neurons prenatally exposed to ethanol (35). Ethanol-induced reduction of calcium entry in developing PCs depolarized by quisqualate application had already been noted (36).

In contrast to observations at the cerebellar level by Coesmans et al. (16), a high calcium threshold for LTP and a low calcium threshold for LTD induction have been demonstrated at the hippocampal level (37, 38). A LTP induction protocol applied to hippocampal pyramidal cells would thus lead to a LTD if calcium entry were reduced. Interestingly, the appearance of such a hippocampal LTD after a LTP induction protocol has been observed in vivo in guinea pigs prenatally exposed to ethanol (39). We believe that, analogous to our demonstration in cerebellar PCs, a reduction of calcium entry through voltage-gated calcium channels in hippocampal pyramidal cells prenatally exposed to ethanol is the best explanation for this observation. The mechanism leading from calcium-mediated cell dysfunction to learning deficits that we suggest at the PC level could also be relevant for noncerebellar deficits in FAS. Intracytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration is also crucial for other aspects of PC electrical properties (40). This might explain the lower intrinsic excitability of PCs in FAS mice presenting reduced voltage-gated calcium currents.

The proposed sequence of events leading from decreased calcium currents into PCs to learning deficits and ataxia may result from reduced current activation, increased current inactivation, or reduced calcium channel expression. We demonstrated that the expression of voltage-gated calcium channels involved in the high-voltage calcium current (L, P/Q, and N types) was not reduced in FAS (SI Fig. 6 B–D). We also demonstrated that the inactivation time constant is similar in FAS and control PCs (SI Fig. 6A). This suggests that a reduced activation of calcium channels is responsible for the reduced current.

The activation/inactivation of calcium channels is known to be modulated by different intracellular signaling cascades involving G proteins, cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA), protein kinase C, and calcium/calmodulin (41). Because the calcium/calmodulin modulation alters the inactivation kinetics of VGCC (42–44) and because the inactivation time constant was not altered in our FAS model (SI Fig. 6A), this mechanism can be ruled out. Some studies have found increased cAMP levels or PKA activity in FAS (45, 46); this would lead to an increased calcium current (41), so this mechanism can also be ruled out in our model because a reduction of the calcium current was observed. The activity of G proteins appears unchanged in FAS (47). Finally, PKC directly increases the activity of Cav1.2 and Cav2 channels and reverses G protein inhibition of these channels (41). PKC expression and/or activity have been found to be reduced in FAS models (21, 22). Accordingly, we found that the expression of membrane PKCγ [the main isoform expressed in PCs and not in other cerebellar neurons as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry (21) and in situ hybridization (23)] is significantly reduced in the cerebellum of FAS mice as demonstrated by Western blotting. We have then tested the effect of a PKC activator and a PKC inhibitor on the maximal amplitude of voltage-dependent calcium current. Our data show that PKC inhibition has a significant impact on calcium current amplitude in control mice but not in FAS mice, whereas PKC activation has no significant effect in control mice but is able to increase calcium current amplitude in FAS mice. These data suggest that basal phosphorylation of voltage-dependent calcium current is lacking in FAS and can be recovered by PKC activation. We conclude that the reduced expression of PKC causes the reduction in amplitude of calcium current in FAS PCs, compared with controls, through an alteration of the phosphorylation state and of the activation of these channels.

The reduced expression of PKCγ might also contribute to LTD alteration because PKCγ inhibition blocks LTD induction in PCs (48, 49). Because the present FAS model is not specific for PKCγ underexpression or inhibition, it is difficult to compare it with PKCγ knockout mice that present a cerebellar LTD that is much less sensitive to PKCγ inhibitors (49) than wild-type mice, probably because of the compensatory activation of other kinases. Finally, the involvement of glutamate receptors at the level of excitatory synapses onto PCs in FAS could not be excluded.

Our results demonstrate both in vivo and in vitro neuronal dysfunction of surviving FAS PCs that may be explained by altered calcium dynamics. The relevance of this dysfunction in the pathogenesis of learning deficits provides new opportunities for therapeutic intervention in FAS.

Methods

Mouse Model.

FAS and control mice were generated from 3- to 5-month-old NMRI mice drinking ad libitum a water solution containing either ethanol 18% or sucrose 25% from one day before mating until delivery. At birth, ethanol was replaced by sucrose. This study was approved by local ethical committees.

Immunohistochemistry and Western blots were performed as described in SI Materials and Methods.

Motor Coordination.

Accelerating rotarod and runway tests were performed as described in SI Materials and Methods on postnatal days 24–26 and 26–28, respectively. Tests were repeated after a 3-week trial-free period.

Eyelid conditioning was performed as described in SI Materials and Methods. Briefly, mice were conditioned each day by the association (10 blocks of nine associations plus one conditioned stimulus alone) of an unconditioned stimulus (100-ms air puff on the eyelid) and coterminated conditioned stimulus (80-db, 1-kHz, 370-ms tone). Daily percentage of significant EMG response to conditioned stimulus alone was counted.

Patch-Clamp Recordings and Calcium Imaging on Brain Slices.

Acute cerebellar slices were prepared from 15- to 20-day-old mice, and patch-clamp recordings were performed. Calcium imaging was performed as described (50). Parallel fibers and climbing fibers were stimulated as described (51, 52). LTD recordings were obtained as described (53, 54) through parallel fiber stimulation in conjunction with a depolarizing pulse applied to PCs. These techniques are detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Single Unit Recording in Alert Mice.

One- to 2-month-old FAS and control mice were prepared for PCs, and local field potential and recordings were performed in alert immobilized mice 24 h later by using glass micropipettes as described (25) and as detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Data Analyses and Statistics.

Results are reported and illustrated as mean ± SEM. Unless otherwise mentioned, means and variance were compared by using t and F test, respectively. All statistical analyses were performed by using STATISTICA 6.0 (Statsoft, Maisons-Alfort, France).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Cuvelier, P. Demaret, C. Waroquier, P. Kelidis, and M. P. Dufief for expert assistance. R.H. and L.S. were supported by the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS) (Belgium). This work was supported by the Fondation Médicale Reine Elisabeth, FNRS, Ministère des Affaires Sociales et de la Santé Publique (Belgium), the Van Buuren Foundation, Action de Recherche Concertée (2002–2007), and research funds of ULB and UMH.

Abbreviations

- EPSC

excitatory postsynaptic current

- FAS

fetal alcohol syndrome

- LFPO

local field potential oscillation

- LTD

long-term depression

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- PC

Purkinje cell

- VGCC

voltage-gated calcium channels.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0607037104/DC1.

References

- 1.Burd L, Cotsonas-Hassler TM, Martsolf JT, Kerbeshian J. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2003;25:681–688. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2003.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burd L, Martsolf JT. Physiol Behav. 1989;46:39–43. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90318-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer-Moffett C, Altman J. Brain Res. 1977;119:249–268. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90310-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierce DR, Williams DK, Light KE. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1650–1659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Backman C, West JR, Mahoney JC, Palmer MR. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1137–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas JD, Goodlett CR, West JR. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;105:159–166. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heaton MB, Mitchell JJ, Paiva M. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:512–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards RB, Manzana EJ, Chen WJ. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1003–1009. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000021148.70836.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mullen RJ, Eicher EM, Sidman RL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:208–212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feddersen RM, Ehlenfeldt R, Yunis WS, Clark HB, Orr HT. Neuron. 1992;9:955–966. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90247-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feddersen RM, Clark HB, Yunis WS, Orr HT. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1995;6:153–167. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1995.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miall RC, Keating JG, Malkmus M, Thach WT. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:13–15. doi: 10.1038/212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenyon GT, Medina JF, Mauk MD. J Comput Neurosci. 1998;5:71–90. doi: 10.1023/a:1008830427738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goossens J, Daniel H, Rancillac A, van der SJ, Oberdick J, Crepel F, De Zeeuw CI, Frens MA. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5813–5823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05813.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koekkoek SK, Hulscher HC, Dortland BR, Hensbroek RA, Elgersma Y, Ruigrok TJ, De Zeeuw CI. Science. 2003;301:1736–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.1088383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coesmans M, Weber JT, De Zeeuw CI, Hansel C. Neuron. 2004;44:691–700. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung YH, Shin CM, Kim MJ, Shin DH, Yoo YB, Cha CI. Brain Res. 2001;903:247–252. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02392-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park SK, Hwang IK, An SJ, Won MH, Kang TC. Mol Cell. 2003;16:297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pouille F, Cavelier P, Desplantez T, Beekenkamp H, Craig PJ, Beattie RE, Volsen SG, Bossu JL. J Physiol. 2000;527(Pt 2):265–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe S, Takagi H, Miyasho T, Inoue M, Kirino Y, Kudo Y, Miyakawa H. Brain Res. 1998;791:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McIntyre TA, Souder MG, Hartl MW, Shibley IA. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;117:191–197. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanner DC, Githinji AW, Young EA, Meiri K, Savage DD, Perrone-Bizzozero NI. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:113–122. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000106308.50817.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barmack NH, Qian Z, Yoshimura J. J Comp Neurol. 2000;427:235–254. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001113)427:2<235::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bareggi R, Narducci P, Grill V, Lach S, Martelli AM. Biol Cell. 1996;87:55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheron G, Gall D, Servais L, Dan B, Maex R, Schiffmann SN. J Neurosci. 2004;24:434–441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3197-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Servais L, Cheron G. Neuroscience. 2005;134:1247–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bearzatto B, Servais L, Roussel C, Gall D, Baba-Aissa F, Schurmans S, de Kerchove, dA , Cheron G, Schiffmann SN. FASEB J. 2006;20:380–382. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3785fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheron G, Servais L, Wagstaff J, Dan B. Neuroscience. 2005;130:631–637. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Servais L, Bearzatto B, Schwaller B, Dumont M, De Saedeleer C, Dan B, Barski JJ, Schiffmann SN, Cheron G. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:861–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato Y, Miura A, Fushiki H, Kawasaki T. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:1082–1090. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.4.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montarolo PG, Palestini M, Strata P. J Physiol. 1982;332:187–202. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mameli M, Zamudio PA, Carta M, Valenzuela CF. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8027–8036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2434-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson RF, Krupa DJ. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:519–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Offenhauser N, Castelletti D, Mapelli L, Soppo BE, Regondi MC, Rossi P, D'Angelo E, Frassoni C, Amadeo A, Tocchetti A, et al. Cell. 2006;127:213–226. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee YH, Spuhler-Phillips K, Randall PK, Leslle SW. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:921–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb05272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gruol DL, Parsons KL. Brain Res. 1996;728:166–174. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cummings JA, Mulkey RM, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Neuron. 1996;16:825–833. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cormier RJ, Greenwood AC, Connor JA. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:399–406. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richardson DP, Byrnes ML, Brien JF, Reynolds JN, Dringenberg HC. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1593–1598. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berridge MJ. Neuron. 1998;21:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Felix R. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2005;25:57–71. doi: 10.1081/rrs-200068102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zuhlke RD, Pitt GS, Deisseroth K, Tsien RW, Reuter H. Nature. 1999;399:159–162. doi: 10.1038/20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee A, Wong ST, Gallagher D, Li B, Storm DR, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Nature. 1999;399:155–159. doi: 10.1038/20194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peterson BZ, DeMaria CD, Adelman JP, Yue DT. Neuron. 1999;22:549–558. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumada T, Lakshmana MK, Komuro H. J Neurosci. 2006;26:742–756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4478-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Constantinescu A, Wu M, Asher O, Diamond I. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43321–43329. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Druse MJ, Tajuddin NF, Eshed M, Gillespie R. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:47–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Linden DJ, Connor JA. Science. 1991;254:1656–1659. doi: 10.1126/science.1721243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen C, Kano M, Abeliovich A, Chen L, Bao S, Kim JJ, Hashimoto K, Thompson RF, Tonegawa S. Cell. 1995;83:1233–1242. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kano M, Schneggenburger R, Verkhratsky A, Konnerth A. Neurosci Res. 1995;24:87–95. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(95)00978-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Llano I, Marty A, Armstrong CM, Konnerth A. J Physiol. 1991;434:183–213. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sacchetti B, Scelfo B, Tempia F, Strata P. Neuron. 2004;42:973–982. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Konnerth A, Dreessen J, Augustine GJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7051–7055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barski JJ, Hartmann J, Rose CR, Hoebeek F, Morl K, Noll-Hussong M, De Zeeuw CI, Konnerth A, Meyer M. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3469–3477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03469.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.