Abstract

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is an anion channel, mutations of which cause cystic fibrosis, a disease characterized by defective Cl− and HCO3− transport. Although >95% of all CF male patients are infertile because of congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens (CBAVD), the question whether CFTR mutations are involved in other forms of male infertility is under intense debates. Here we report that CFTR is detected in both human and mouse sperm. CFTR inhibitor or antibody significantly reduces the sperm capacitation, and the associated HCO3−-dependent events, including increases in intracellular pH, cAMP production and membrane hyperpolarization. The fertilizing capacity of the sperm obtained from heterozygous CFTR mutant mice is also significantly lower compared with that of the wild-type. These results suggest that CFTR in sperm may be involved in the transport of HCO3− important for sperm capacitation and that CFTR mutations with impaired CFTR function may lead to reduced sperm fertilizing capacity and male infertility other than CBAVD.

Keywords: bicarbonate, CFTR, sperm capacitation

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a common hereditary disease caused by mutations of the gene encoding cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a cAMP-activated anion channel, with clinical manifestations of progressive lung disease, pancreatic insufficiency, and infertility in both sexes (1, 2). CF male patients are infertile mostly due to congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens (CBAVD) and obstructive azoospermia. The absence of sperm in the ejaculatory duct of CF males has led to the overlook of possible involvement of CFTR in normal sperm function. Studies have reported a higher prevalence of CFTR gene mutations in otherwise healthy men presenting with reduced sperm quality compared with controls with normal sperm parameters (3). Interestingly, a recent study showed that in infertile males, the frequency of CFTR heterozygosity is 2-fold higher than in the general population (4), which suggests possible involvement of CFTR mutations in other forms of male infertility. However, the exact role of CFTR in this context remains obscure.

Mammalian sperm are unable to fertilize eggs until they undergo an activation process, known as capacitation, in the female reproductive tract (5, 6). Capacitation is known to be associated with elevation of intracellular pH (7) and hyperpolarization of the sperm plasma membrane (8) and these events have been shown to depend on extracellular HCO3− (9, 10). The regulatory role of HCO3− in sperm capacitation has been attributed to its direct activation of a HCO3−-sensitive soluble form of adenylyl cyclase (11) that in turns activates cAMP production and various downstream cellular events, such as protein tyrosine phosphorylation, leading to capacitation (12–14). Despite the mounting evidence indicating the key importance of HCO3− in sperm capacitation, the transporting mechanism responsible for the entry of HCO3− into sperm remains poorly understood.

CFTR is a channel protein known to conduct both Cl− and HCO3−, defects of which due to its gene mutations cause CF, although the exact mechanisms underlying most of the clinical manifestations remain elusive (15–18). Recent studies have indicated a significant role of CFTR, either direct or indirect, in HCO3− secretion and the possible involvement of defective CFTR-mediated HCO3− secretion in the pathogenesis of CF (19). Our study in ref. 20 demonstrated a direct role of CFTR in mediating uterine HCO3− secretion, impairment of which leads to reduced sperm capacitation and the fertilizing capacity of sperm. The demonstrated dependence of sperm capacitation on the HCO3− content of the uterine tract, the ability of CFTR to conduct HCO3−, and the reported higher prevalence of CFTR gene mutations in otherwise healthy men presenting with reduced sperm quality compared with that obtained from normal subjects, have prompted us to hypothesize that CFTR may also be expressed in sperm and play a role in mediating the HCO3− entry important for the fertilizing capacity of sperm.

Results and Discussion

Expression and Localization of CFTR in Human and Mouse Spermatozoa.

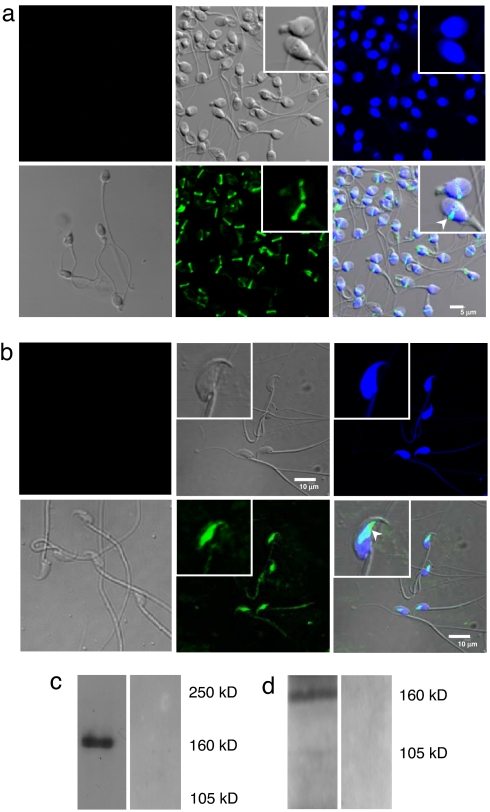

Although CFTR expression has been shown in the testis of rodents (21) and rat germ cells (22), its expression and function in mature sperm have not been demonstrated. We first examined the expression of CFTR in both human and mouse sperm, using immunofluorescence staining and Western blot analysis. Sperm were either donated by volunteers with proven fertility or collected from the cauda epididymides of adult ICR (an outbred Institute for Cancer Research strain) mice. Using confocal imaging, CFTR was immunolocalized to the equatorial segment of human and mouse sperm (Fig. 1 a and b). In Western blot analysis, a mouse anti-human CFTR monoclonal antibody (C-terminal; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) detected a band of ≈160 kDa in human sperm, and a polyclonal rabbit antibody [Alomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel); catalog no. ACL-006] raised against the C-terminal of mouse CFTR also revealed the presence of CFTR in mouse sperm (Fig. 1 c and d).

Fig. 1.

Expression and localization of CFTR in human and mouse spermatozoa. (a) Immunostaining of CFTR in human sperm, using a monoclonal human CFTR antibody (1:500; Abcam) and the bound antibody detected with Alex 488-conjugated secondary antibody, and confocal imaging with images of the same field (enlargement in Insets): differential interference contrast image (Upper Center); sperm nuclei stained with DAPI (Upper Right); immunostaining of CFTR showing positive staining in the equatorial segment (Lower Center); superimposed image of DAPI and CFTR staining (Lower Right and Inset; arrow indicates CFTR localization). Upper Left image is the negative immunostaining control of CFTR with the mouse isotype specific IgM, whereas Lower Left is the corresponding differential interference contrast image. (Scale bar, 5 μm.) (b) Immunofluorescence of CFTR in mouse sperm with corresponding images as depicted in a, showing CFTR localization in the equatorial segment of mouse sperm. (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (c) Western blotting analysis of human sperm CFTR protein probed by monoclonal CFTR antibody (1:1,000; R&D Systems) (left lane) or with normal mouse IgG control (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; catalog no. Sc-2762) (right lane). (d) Identification of CFTR in mouse sperm by Western blot analysis probed by polyclonal CFTR antibody (1:500) (Alomone Labs; catalog no. ACL-006). This antibody recognizes a band at expected mouse CFTR MW 160 kDa (left lane), which is specifically blocked by the preincubation of immunizing CFTR peptides (Alomone Labs; catalog no. ACL-006) (right lane).

Involvement of CFTR in Sperm Capacitation-Related and Bicarbonate-Dependent Processes.

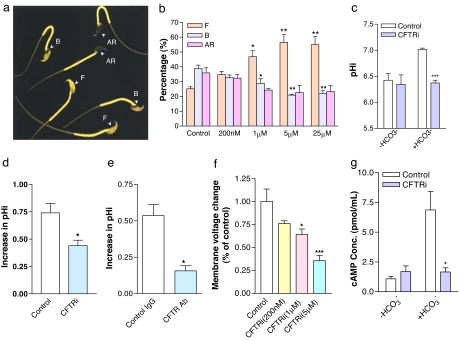

We then addressed the question whether CFTR is involved in mediating the HCO3− entry important for sperm capacitation. Mouse sperm were collected from the cauda epididymis and incubated in Biggers, Whitten, and Whittingham (BWW) medium for induction of capacitation. CFTR inhibitor-172, a specific CFTR channel blocker (23), was added during incubation, and its effect on sperm capacitation was assessed by chlortetracycline (CTC) staining, a conventional method for assessing sperm capacitation based on alteration in staining patterns of the sperm head during the process, with F pattern indicating incapacitated, B pattern for capacitated, and AR for capacitated and acrosome-reacted sperm (Fig. 2a). As shown in Fig. 2b, the CFTR inhibitor concentration dependently reduced the percentage of capacitated sperm, as evidenced by the increased percentage of sperm exhibiting F pattern and the reduced percentage with B pattern, indicating the involvement of CFTR in sperm capacitation. Because sperm capacitation depends on HCO3− entry, the effect CFTR inhibitor has on sperm capacitation could be due to its blocking of the channel for HCO3− entry. We then tested whether the CFTR inhibitor or antibody could inhibit the capacitation-associated intracellular pH increase that is due to HCO3− entry. After incubated with capacitation-inducing media for 2 h in the presence of the CFTR inhibitor (1 μM), sperm were loaded with a pH-sensitive dye, 2′,7′-bis-2(2-carbosyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescence, acetoxymethyl ester, for measurement of intracellular pH. As shown in Fig. 2c, although this inhibitor had no significant effect on the intracellular pH of sperm incubated in HCO3−-free medium, it significantly inhibited the HCO3−-induced intracellular pH increase during the capacitation process (P < 0.001). To further confirm that CFTR is involved in mediating HCO3− influx in sperm, we also performed single cell imaging experiment, in which the HCO3−-induced change in intracellular pH could be monitored in real time. The result (Fig. 2d) showed that addition of HCO3− produced an increase in pHi that was inhibited when sperm were preincubated with CFTRinh-172 (P < 0.05). These data confirmed that CFTRinh-172 was indeed able to inhibit the HCO3−-induced pH increase in sperm. A monoclonal CFTR antibody (1:500 dilution; Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA; catalog no. ALX-804-214), which had been shown to inhibit CFTR function (24), was also found to have significant inhibitory effect on sperm intracellular pH increase (P < 0.05; Fig. 2e), consistent with the involvement of CFTR in mediating HCO3− entry during capacitation.

Fig. 2.

Involvement of CFTR in sperm capacitation-related and bicarbonate-dependent processes. (a) Distinct CTC fluorescence staining patterns in sperm (with arrowheads indicating different patterns). (b) The percentage of incapacitated (F pattern) and capacitated sperm (B pattern) enhanced and attenuated, respectively, by the CFTR inh-172 (CFTRi) in a concentration-dependant manner. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01 when compared with respective controls. (c) CFTRi (1 μM) attenuated intracellular pH increase, measured with 2′,7′-bis-2(2-carbosyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescence, acetoxymethyl ester in sperm incubated for 2 h in HCO3−-containing capacitating medium (+HCO3−) (P < 0.05) but without effect in HCO3−-free medium (−HCO3−). (d and e) Pretreatment with CFTRi (1 μM) (d) and monoclonal CFTR antibody (1:500 dilution) (e) for15 min attenuated HCO3− (5 mM)-induced increase in intracellular pH measured by real-time single cell imaging experiments. (f) Concentration-dependent effect of the CFTR inhibitor on the amplitude of HCO3−-induced hyperpolarization. (g) Effect of CFTR inhibitor on the HCO3−-stimulated cAMP production in sperm. Spermatozoa were preincubated in BWW media (−HCO3−) with or without 5 μM CFTRi for 10 min and then challenged with the same volume of 25 mM HCO3− (or same volume of HCO3−-free medium) for 1 min before cAMP measurement. In each experiment, the control group was challenged with the same volume/concentration of vehicle (Me2SO) or control antibody as the experimental group. Normal mouse IgG control (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; catalog no. Sc-2762) was used as a control for CFTR antibody. For all statistic figures, data are shown as mean ± SEM; n = 3; ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01; ∗∗∗, P < 0.001 vs. control).

Because HCO3− is negatively charged, its entry into sperm could induce membrane hyperpolarization, a process known to be associated with sperm capacitation (10). We then examined the effect of the CFTR inhibitor on HCO3−-induced membrane hyperpolarization by monitoring sperm membrane potential changes with a membrane potential-sensitive fluorescent dye DiSC3 (5). Sperm were originally incubated in HCO3−-free solution, and upon addition of extracellular HCO3− (5 mM), a membrane hyperpolarization in the sperm could be observed, which could be reversed by the CFTR inhibitor in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2f), confirming the involvement of CFTR in mediating HCO3− entry into sperm.

It is now established that the regulatory effect of HCO3− on capacitation is mediated by its direct activation of a soluble adenylyl cyclase in sperm (11). Numerous studies have shown that the stimulation of soluble adenylyl cyclase activity in sperm by HCO3− leads to an increase in cAMP production and phosphorylation of tyrosine kinase, one of the main downstream targets of cAMP, leading to sperm capacitation (12). In the present study, the ELISA measurement indeed showed that a >6-fold increase in sperm cAMP production could be induced by 25 mM HCO3− compared with that incubated in HCO3−-free medium (Fig. 2g). Pretreatment with CFTR inhibitor (5 μM) in the absence of HCO3− did not significantly affect the cAMP production but significantly reduced the HCO3−-induced cAMP increase (P < 0.05; Fig. 2g), suggesting that this process, which is vital to sperm capacitation, depends on CFTR. The observations that CFTR inhibitor or antibody could inhibit sperm capacitation as well as a number of HCO3−-dependent and capacitation-associated events are consistent with a role of CFTR in mediating HCO3− entry important for sperm capacitation.

Demonstration of Reduced HCO3− Transport in Sperm of Heterozygous Cftr+/− Mice.

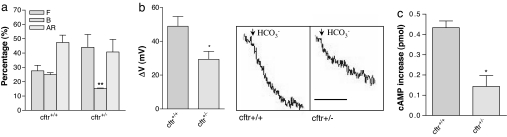

To further confirm the role of CFTR in sperm capacitation and thus the fertilizing capacity of sperm, we examined sperm capacitation and fertility in a CF mouse model, CFTRtm1Unc, with a phenotype similar to the CF disease-causing ΔF508 mutation in humans (25). Because the homozygous mutant mice show CF phenotypes and often die before puberty, it is not feasible to use the homozygous mutant mice. Instead, heterozygous mutant mice could be used, because the heterozygous CFTR mutant mice (Cftr+/−) have been shown to have impaired CFTR function, i.e., reduced Cl− and fluid secretion (26) or fewer CFTR-mediated translocated Salmonella typhi into the gastrointestinal submucosa (24) compared with the wild-type (Cftr+/+) mice. A recent study also showed that in infertile males, the frequency of CFTR heterozygosity is 2-fold higher than that in the general population, indicating possible dosage effect of CFTR on the fertility (4). We therefore examined whether the sperm from the Cftr+/− mice show reduced ability to undergo capacitation compared with those from wild-type littermates (C57BL/6J background). The results showed that after 2-h incubation in the capacitation-inducing medium, the percentage of capacitated sperm (B pattern), as demonstrated by CTC staining, of the heterozygous mutant mice was significantly lower than that of the wild-type control (P < 0.01; Fig. 3a). We then tested whether the reduced capacitation was due to a defect in transporting HCO3− in sperm of Cftr+/− mice by measuring HCO3−-induced membrane hyperpolarization. The magnitude of the HCO3−-induced membrane hyperpolarization in Cftr+/− sperm was indeed significantly reduced compared with the wild-type control (P < 0.05; Fig. 3b), suggesting a defect in HCO3− transport in Cftr+/− sperm. The cAMP increase in response to HCO3− in Cftr+/− sperm was also reduced compared with that in the wild-type control (P < 0.05; Fig. 3c), confirming that a defect in CFTR affects the HCO3−-dependent events important for sperm capacitation.

Fig. 3.

Demonstration of reduced HCO3− transport in sperm of heterozygous Cftr+/− mice. (a) CTC staining results showing significantly lower percentage of capacitated sperm (exhibiting B pattern) in Cftr+/− compared with the wild-type sperm. (b) Cftr+/− sperm exhibit a reduced HCO3−-induced membrane hyperpolarization compared with wild-type control. The membrane voltage changes after the addition of 5 mM HCO3− were compared among the wild-type (n = 4) and heterozygous sperm (n = 4). (Right) Shows the corresponding representative tracing (scale bar indicate 1 min). (c) Sperm of Cftr+/− mice (n = 3) show reduced HCO3−-induced cAMP increase compared with wild-type control (n = 3). Sperm incubated with HCO3−-free medium were challenged with 25 mM HCO3− for 30 s before cAMP measurement. cAMP increase were compared between Cftr+/− mice and wild-type control. Errors bars are SEM. ∗, P < 0.05 and ∗∗, P < 0.01 vs. control.

Demonstration of Reduced Fertility in Vitro and in Vivo in Heterozygous Cftr+/− Mice.

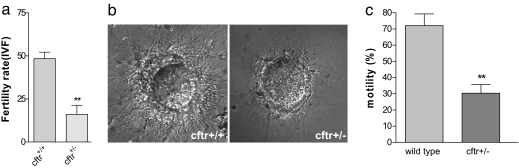

Because capacitation is a necessary process of sperm activation before fertilization, impaired sperm capacitation because of defective CFTR is expected to affect fertility outcome both in vitro and in vivo. We performed in vitro fertilization to compare the fertilizing capacity of heterozygous Cftr+/− sperm to that of Cftr+/+ sperm. Oocytes were obtained from wild-type female mice and incubated with the Cftr+/− sperm. The in vitro fertility rate was determined as the ratio of two-cell embryos obtained to the total number of the oocytes used. The results showed that the percentage of fertilized eggs when incubated with Cftr+/− sperm (13 of 73, 16%) was significantly lower than that with Cftr+/+ sperm (28 of 60, 48.5%) (P < 0.01; Fig. 4a). The impaired fertilizing capacity in Cftr+/− sperm could also be evidenced by their reduced binding and penetration of zona pellucida-free eggs compared with the wild-type sperm (Fig. 4b). To further demonstrate the role of CFTR in male fertility in a physiological context, we examined the fertility rate of male Cftr+/− mice through natural mating. Cftr+/+ female mice housed overnight with Cftr+/− males showed normal number of vaginal plugs the following morning. However, only five of the nine Cftr+/− males tested had offspring, compared with 100% of the age matched wild-type males having offspring, and the averaged litter size in females mated with the Cftr+/− males was also reduced (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Demonstration of reduced fertility in vitro and in vivo and decreased motility in heterozygous Cftr+/− mice. (a) In vitro fertilization result showing reduced percentage of oocyte fertilized with sperm from Cftr+/− mice compared with wild-type sperm. The total number of eggs tested was 60 (incubated with wild-type sperm) and 73 (incubated with Cftr+/− sperm), respectively. ∗∗, P < 0.01. (b) Representative phase-contrast images of zona pellucida-free oocytes after sperm-egg incubation for 4 h, showing reduced binding or penetration by Cftr+/−sperm (Right) compared with wild-type sperm (Left). (c) Comparison of sperm motility between wild-type and heterozygous CF mice sperm. After 10 min incubation in complete medium, the sperm were washed with sperm washing medium, and the motile and total sperm were counted. For each mouse, at least 200 sperm were scored. The decrease in motility was confirmed by using computer-assisted sperm analysis (n = 3).

Table 1.

Comparison of in vivo fertility outcome between Cftr+/+ and Cftr+/− mice

| Mice | Total pups | Pups per litter ± SEM | Fertility, % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cftr+/+ (n = 9) | 56 | 6.22 ± 0.67 | 100% (9) |

| Cftr+/− (n = 9) | 21 | 4.20 ± 1.09** | 55.4% (5) |

**, P < 0.01.

It should be noted that apart from capacitation, other sperm functions, such as sperm motility, might also be impaired in Cftr+/− mice, contributing to the reduced fertility observed. Indeed, we also observed a significant reduction in sperm motility with compromised forward movement parameters in Cftr+/− mice compared with wild-type control (Fig. 4c and Table 2). These findings are also in line with a role of CFTR in transporting HCO3−, because HCO3− has also been linked to sperm motility (27, 28). Taken together, these results have confirmed that defective CFTR in sperm leads to compromised fertilizing capacity of sperm. The reduced fertility in Cftr+/− mice may stem from less functional CFTR in the heterozygous mice, because it has been reported by others (29) that less (but a detectable amount) wild-type CFTR mRNA was present in multiple tissues of heterozygote CFTRtm1Unc mice.

Table 2.

Movement parameters of sperm recovered from wild-type and Cftr+/− mice

| Parameters | Wild type | Cftr+/− |

|---|---|---|

| VAP(μ m s-1) | 48.8 ± 2.6 | 40.4 ± 2.1* |

| VSL(μ m s-1) | 36.2 ± 2.0 | 29.3 ± 1.9* |

| VCL(μ m s-1) | 82.0 ± 3.1 | 70.3 ± 2.2* |

n = 3. Data were obtained by using computer-assisted sperm analysis and are expressed as mean ± SEM.

*, P < 0.05 compared with corresponding values (unpaired t test). VAP, averaged path velocity; VSL, straight line velocity; VCL, curvilinear velocity.

Although CFTR has long been thought to function as a chloride channel, emerging evidence indicates that it can also transport HCO3− directly or indirectly (19). The role of CFTR in transporting HCO3− has been mainly associated with epithelial secretion, thereby regulating the luminal pH thought to be important for the physiological function of a number of organs, including the nasal epithelial (30) and airways (31). Here, we demonstrate the involvement of CFTR in transporting HCO3− in nonsomatic cells, namely the sperm, thereby eliciting the cAMP-dependent signaling pathway on which sperm capacitation depends. CFTR in sperm membrane may act as a HCO3−-conducting channel, as demonstrated in other tissues, including the endometrial epithelium (20). Interestingly, the capacitation-associated and HCO3−-dependent events were not significantly augmented by forskolin, a cAMP-evoking agent shown to activate CFTR (data not shown). This suggests that the CFTR channel in sperm, as shown in the airways (32), is open at basal level, allowing the entry of HCO3− when sperm encounter the HCO3−-rich uterine fluid. Alternatively, CFTR may facilitate HCO3− transport by acting as a Cl− channel that either affects membrane voltage, thereby providing the driving force for the electrogenic Na/ HCO3− cotransporter (10), or provides a Cl− recycling pathway required for the operation of a Cl− / HCO3− exchanger (33), as in the case of pancreatic HCO3− secretion (34). Interestingly, defective CFTR has been shown to affect the expression and function of these HCO3− transporter in the tracheal epithelial cells resulting in defective HCO3− secretion (35). Nevertheless, whether it is involved in HCO3− transport directly or indirectly in sperm, CFTR is important for the fertilizing capacity of sperm, as demonstrated in the present study.

The presently demonstrated and previously unsuspected role of CFTR in sperm function may unravel the mysteries of many unexplained cases of male infertility, because >1,200 mutations in CFTR have been identified since its discovery with various defects (2). These mutations may affect CFTR function to different extents, which may explain the observation that certain CFTR mutations are associated with reduced sperm quality in men who do not present CF phenotype. CFTR may also play different roles in sperm function other than HCO3− transport for sperm capacitation, because CFTR is also known to regulate an array of other proteins and cellular processes. Together with the reported involvement of CFTR in HCO3− secretion by the female reproductive tract (20), the present finding of CFTR involvement in sperm capacitation indicates that CFTR may have far-reaching effect on reproduction of both sexes.

Experimental Procedures

Immunofluorescence Straining of CFTR in Human and Mouse Sperm.

For indirect immunofluorescence studies of CFTR localization, sperm were either donated by volunteers with proven fertility or collected from the cauda epididymides of fertile adult ICR mice and washed by centrifugation although a three-layer gradient of Percoll. Sperm were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (we also applied other fixation concentrations from 0.02% to 4%) overnight at 4°C. Sperm were smeared on slide after washing with PBS for three times, air dried, and subsequently blocked with 10% BSA at room temperature for 1 h. After two more washings in PBS (5 min each), sperm were incubated with primary CFTR monoclonal antibody (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, U.K.; catalog no. ab2784) or an equivalent concentration of mouse purified IgM control (gift from M. Gwrish, Department of Immunology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) at 4°C overnight. Sperm were washed with PBS three times and incubated with secondary antibody (1:500, Alex 488-conjugated goat-anti-mouse IgG; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR; catalog no. A-11017) in dark room for 1 h at room temperature. Unbounded antibody was removed by washing with PBS three times for 5 min each and then counterstained with DAPI (Sigma, St. Louis, MO; catalog no. D9564) for 5 min. Finally, sperm were washed with PBS and deionized water once. The slides were stored in dark box before visualization.

Sperm Preparation.

The procedure for retrieving sperm is as follows: Cauda epididymides were dissected from adult ICR mice and minced, then placed in a modified human tubal fluid medium (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) to allow dispersion of sperm. After 10 min, sperm in the suspension were washed in 10 ml of the same medium by centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min at room temperature (24°C). Sperm were then resuspended to a final concentration of 2 × 107 cells per ml and diluted in the appropriate medium depending on the experiment performed.

Assessment of Sperm Capacitation and Fertilization.

Sperm capacitation in mice was detected by CTC staining as described in ref. 20. A total of at least 200 sperm were counted to assess the different CTC staining patterns recognized previously. B and AR patterns were taken to indicate capacitated sperm: The B pattern was capacitated and acrosome-intact sperm; the AR pattern was capacitated and acrosome-reacted sperm. The methods for in vitro fertilization in mice followed those described in ref. 20.

Measurement of Intracellular pH in Spermatozoa.

Caudal epididymal spermatozoa were obtained from adult (8–14 week) ICR mice. Spermatozoa were collected and adjusted to 2 × 106 cells/ml with complete BWW medium (95 mM NaCl/44 μM sodium lactate/25 mM NaHCO3/20 mM Hepes/5.6 mM d-glucose/4.6 mM KCl/1.7 mM CaCl2/1.2 mM KH2PO4/1.2 mM MgSO4/0.27 mM sodium pyruvate/0.3% wt/vol BSA, 5 units per ml penicillin/5 μg/ml streptomycin, pH 7.4). Cells were then incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C with the appropriate inhibitor added. When needed, 5 μM 2′,7′-bis-2(2-carbosyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescence, acetoxymethyl ester was added, and the incubation continued for a further 30 min. Afterward, the cells were pelleted and washed twice to remove free dye and adjust to 2 × 106 cells per ml. To determine the intracellular pH (pHi), the fluorescence signal was recorded by a LS-50B luminescent spectrometer (PerkinElmer Optoelectronics, Fremont, CA). A radiometric analysis of fluorescence data, using excitation wavelengths of 490/440 nm and an emission of 530 nm (8-nm excitation/emission bandpass), was performed. Calibration was performed as described in ref. 10.

Single-Cell Intracellular pH Measurement.

The chambers for imaging were prepared by coating coverslips with 50 μg/ml polyd-lysine, shaking off excess and allowing to air-dry. Sperm (2 × 107 cells per ml) were loaded with 3 μM 2′,7′-bis-2(2-carbosyethyl)-5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescence, acetoxymethyl ester (Molecular Probes) for 15 min at 37°C. The dye-loaded sperm were then centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000 × g and resuspended in the original volume of medium. Labeled sperm were diluted 1:2 in the HCO3−-free medium, placed in the chamber immediately, and left for 1–3 min, after which the unattached sperm were removed by washing with HCO3−-free medium. The chamber was then mounted on the microscope (IX70; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with ×40 fluor objective, and fluorescence changes were recorded on a CCD camera used in continuous acquisition mode. The ratio (490:440) of two signals is directly proportional to the pH, and the images were captured by using MetaFluor from Universal Imaging (Washington, DC).

Evaluation of Sperm Plasma Membrane Potential Changes.

Sperm plasma membrane changes were monitored by using the potential-sensitive fluorescent dye DiSC3 (5) (Molecular Probes) as described in ref. 10. We use DiSC3 (5) instead of other membrane voltage dyes because it allows for internal calibration and has been used in monitoring sperm voltage change successfully (10). Briefly, 2 × 106 cells per ml spermatozoa isolated as described above were placed in a thermostatically controlled cuvette at 37°C in BWW medium. Eight minutes before the measurement, 1 μM DiSC3 (5) (final concentration) was added to the sperm suspension and further incubated for 5 min, and when used, 1 μM carbonylcyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (final concentration) was added, and the sperm were incubated for an additional 2 min. After this period, 3 ml of the suspension was transferred to a gently stirred cuvette at 37°C, and the fluorescence (620-/670-nm excitation/emission) was recorded continuously. After reaching a steady fluorescence, calibration was performed as described in ref. 10.

cAMP Measurement.

Sperm were incubated in BWW medium (HCO3−-free) for 10 min with or without the CFTR inhibitor (5 μM), then counted, adjusted to 107 cells per ml, and divided into various treatment groups. Fifty microliters of sperm suspension was added to an equal volume of medium with or without 25 mM HCO3−. Incubations were ended by the addition of 5 vol of ice-cold 10 mM HCl in 100% ethanol. Samples were kept on ice for 15 min, then lyophilized and assayed for cAMP (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI) following the manufacturer's protocol for acetylated samples.

Sperm Motility Analysis.

For the motility analysis, we used an HTM-IVOS system (version 10.8, Hamilton–Thorne Research, Beverly, MA) with the following settings: objective, ×4; minimum cell size, five pixels; minimum contrast, 56; low VAP cut-off, 5.4; low VSL cut-off, 6.2; threshold straightness, 80%; static size limits, 1.00–1.68; static head intensity, 0.41–0.93; magnification, ×2.21. Sixty frames were acquired at a frame rate of 60 Hz. At least 200 tracks were measured for each specimen at 37°C. The playback function of the system was used to check its accuracy.

Statistics.

For two groups of data, two-tail Student's t tests were used. For three or more groups, data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's post hoc test. A probability of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Xu Peng for his help in preparing for confocal imaging and Dr. M Gwrish (Department of Immunology, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) for the kind gift of mouse IgM. This work was supported by Li Ka Shing Institute of Health Sciences of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, National 973 Program Grant 2006CB504002, National Natural Sciences Foundation of China Grants 30270513 and 30600217, Research Grants Council of Hong Kong Grant CUHK4534/05M, and the collaboration project Grant 1902005 from South China National Research Center. H.C.C. received a Croucher Foundation Senior Research Fellowship.

Abbreviations

- BWW

Biggers, Whitten, and Whittingham

- CBAVD

congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CTC

chlortetracycline.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Quinton PM. FASEB J. 1990;4:2709–2717. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.10.2197151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowe SM, Miller S, Sorscher EJ. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1992–2001. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Ven K, Messer L, van der Ven H, Jeyendran RS, Ober C. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:513–517. doi: 10.1093/humrep/11.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz S, Jakubiczka S, Kropf S, Nickel I, Muschke P, Kleinstein J. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:135–138. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang MC. Nature. 1951;4277:697–698. doi: 10.1038/168697b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Austin CR. Nature. 1952;170:326. doi: 10.1038/170326a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meizel S, Deamer DW. J Histochem Cytochem. 1978;26:98–105. doi: 10.1177/26.2.24069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng Y, Clark EN, Florman HM. Dev Biol. 1995;171:554–563. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parrish JJ, Susko-Parrish JL, First NL. Biol Reprod. 1989;41:683–699. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod41.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demarco IA, Espinosa F, Edwards J, Sosnik J, de la Vega-Beltran JL, Hockensmith JW, Kopf GS, Darszon A, Visconti PE. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7001–7009. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Cann MJ, Litvin TN, Iourgenko V, Sinclair ML, Levin LR, Buck J. Science. 2000;289:625–628. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visconti PE, Bailey JL, Moore GD, Pan D, Olds-Clarke P, Kopf GS. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1995;121:1129–1137. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.4.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Visconti PE, Stewart-Savage J, Blasco A, Battaglia L, Miranda P, Kopf GS, Tezon JG. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:76–84. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Visconti PE, Westbrook VA, Chertihin O, Demarco I, Sleight S, Diekman AB. J Reprod Immunol. 2002;53:133–150. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(01)00103-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welsh MJ, Smith AE. Cell. 1993;73:1251–1254. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90353-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poulsen JH, Fischer H, Illek B, Machen TE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5340–5344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anil M. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;39:292–298. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guggino WB, Stanton BA. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:426–436. doi: 10.1038/nrm1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi JY, Muallem D, Kiselyov K, Lee MG, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Nature. 2001;410:94–97. doi: 10.1038/35065099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang XF, Zhou CX, Shi QX, Yuan YY, Yu MK, Ajonuma LC, Ho LS, Lo PS, Tsang LL, Liu Y, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:902–906. doi: 10.1038/ncb1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trezise AEO, Linder CC, Grieger D, Thompson EW, Meunier H, Griswold MD, Buchwald M. Nat Genet. 1993;3:157–164. doi: 10.1038/ng0293-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong PYD, Li JCH, Cheung KH, Leung GPH, Gong XD. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7:705–713. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.8.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muanprasat C, Sonawane ND, Salinas D, Taddei A, Galietta LJV, Verkman AS. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:125–137. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pier GB, Grout M, Zaidi T, Meluleni G, Mueschenborn SS, Banting G, Ratcliff R, Evans MJ, Colledge WH. Nature. 1998;393:79–82. doi: 10.1038/30006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snouwaert JN, Brigman KK, Latour AM, Malouf NN, Boucher RC, Smithies O, Koller BH. Science. 1992;257:1083–1088. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grubb BR, Gabriel SE. Am J Physiol. 1997;36:258–266. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.2.G258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abaigar T, Holt WV, Harrison RA, del Barrio G. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:32–41. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holt WV, Harrison RA. J Androl. 2002;23:557–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu ZD, Gupta V, Lei DC, Holmes A, Carlson EJ, Gruenert DC. Gene. 1998;211:117–123. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paradiso AM, Coakley RD, Boucher RC. J Physiol (London) 2003;548:203–218. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.034447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coakley RD, Grubb BR, Paradiso AM, Gatzy JT, Johnson LG, Kreda SM, O'Neal WK, Boucher RC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:16083–16088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2634339100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moon S, Singh M, Krouse ME, Wine JJ. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:1208–1219. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.6.L1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melvin JE, Park K, Richardson L, Schultheis PJ, Shull GE. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22855–22861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ko SBH, Zeng WZ, Dorwart MR, Luo X, Kim KH, Millen L, Goto H, Naruse S, Soyombo A, Thomas PJ, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:343–350. doi: 10.1038/ncb1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wheat VJ, Shumaker H, Burnham C, Shull GE, Yankaskas JR, Soleimani M. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:C62–C71. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.1.C62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]