Abstract

The use of peptide–human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I tetrameric complexes to identify antigen-specific CD8+ T cells has provided a major development in our understanding of their role in controlling viral infections. However, questions remain about the exact function of these cells, particularly in HIV infection. Virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes exert much of their activity by secreting soluble factors such as cytokines and chemokines. We describe here a method that combines the use of tetramers and intracellular staining to examine the functional heterogeneity of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells ex vivo. After stimulation by specific peptide antigen, secretion of interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1β, and perforin is analyzed by FACS® within the tetramer-positive population in peripheral blood. Using this method, we have assessed the functional phenotype of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells compared with cytomegalovirus (CMV)-specific CD8+ T cells in HIV chronic infection. We show that the majority of circulating CD8+ T cells specific for CMV and HIV antigens are functionally active with regards to the secretion of antiviral cytokines in response to antigen, although a subset of tetramer-staining cells was identified that secretes IFN-γ and MIP-1β but not TNF-α. However, a striking finding is that HIV-specific CD8+ T cells express significantly lower levels of perforin than CMV-specific CD8+ T cells. This lack of perforin is linked with persistent CD27 expression on HIV-specific cells, suggesting impaired maturation, and specific lysis ex vivo is lower for HIV-specific compared with CMV-specific cells from the same donor. Thus, HIV-specific CD8+ T cells are impaired in cytolytic activity.

Keywords: cytotoxic T lymphocytes, HIV, cytokines, tetramers, perforin

Introduction

CTLs have been shown to play a major role in the control of persisting viruses, including EBV, CMV, and HIV (for a review, see reference 1). However, the exact mechanisms by which CTLs exert their antiviral activity remain unclear. Several methods have been developed to analyze human CTL responses and to study their involvement in the immune response to virus infection. The best-established methods are based on the ability of CTLs to lyse appropriate target cells in vitro. This can be performed under limiting dilution conditions (limiting dilution assay [LDA]) to provide a quantitative measurement of the antigen-specific CTL precursor cells that are able to grow and divide in vitro 1. The use of other recently developed techniques, including the quantification of individual TCR transcripts 2 3, measurement of cytokine production by CD8+ T cells 4, and the IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay 5, has shown that the LDA may significantly underestimate the true frequency of circulating CD8+ T cells with specificity for viral antigens 6 7. More recently, a technique in which tetramers of fluorochrome-bound HLA class I molecules assembled with a single antigenic peptide are used to stain CD8+ T cells with specificity for the particular peptide–HLA complex 8 has proved a major advance in the study of antigen-specific T cells. Analysis of tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry provides a method that reliably quantitates the number of specific CD8+ T cells present in peripheral blood, and can provide additional information about their phenotype through costaining for cell surface markers, including markers of activation 6 9, apoptosis 10, and TCR Vβ usage 11.

All of these methods address different aspects of antigen-specific CD8+ T cell activity. LDA measures the lytic ability of specific CTLs, but is also dependent on their ability to grow and divide in tissue culture conditions. ELISPOT assays examine the ability of antigen-specific CD4+ or CD8+ cells to secrete a single cytokine, usually IFN-γ, on contact with their cognate antigen, but do not address their lytic function or secretion of other soluble factors. It is also not clear that all antigen-specific CD8+ cells are able to produce IFN-γ on specific stimulation. This assumption arises largely from studies of individual CTL clones 12 13, and remains to be unequivocally established for the polyclonal response to human viral infection. The use of peptide–HLA tetrameric complexes to stain antigen-specific CD8+ T cells is based on the ability of their TCR to interact specifically with a complex of the appropriate HLA molecule assembled with a relevant peptide with sufficient avidity to allow read-out by FACS® analysis. Recently, several questions have been raised about the functional significance of the tetramer-staining CD8+ T cell population 14 15 16 17. The functional relevance of tetramer staining is suggested by the correlation with other assays of CTL function, including direct lysis in a 51Cr-release assay 18, LDA and ELISPOT assays 6 7, and the ability of tetramer-sorted cells to differentiate into individual CTL clones 19 20. However, studies in a murine model of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection in which CD4+ T cell help was deficient revealed that the circulating tetramer-staining CD8+ cell population was functionally defective and unable to mediate protection 15. In HIV infection, a cardinal feature is a progressive defect in CD4+ T cell function, which is most marked for HIV-specific CD4+ responses 21. It has therefore been proposed that the ultimate failure of the CD8+ T cell response to control HIV replication arises because the lack of CD4+ T cell help renders these cells nonfunctional 16. We have addressed the functional phenotype of the HIV-specific tetramer-positive CD8+ T cell population by developing a method that combines the precision of tetramer quantification with detailed information about individual CD8+ T cell function.

The release of soluble mediators by CTLs in response to the presentation of specific antigen by an APC is critical to their role in control of infection. These molecules include cytokines, such as IL-2, IFN-γ, or TNF-α, chemokines (e.g., regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted [RANTES]), and cytotoxins (e.g., perforin). The properties of these different mediators are highly heterogeneous, contributing to the diversity of CTL function. For human CTL clones, the pattern of cytokine release may differ between individual CTLs, in a similar manner to that described for CD4+ T cell lines and clones. The use of FACS® analysis of cells subjected to intracellular staining for cytokines and chemokines in response to mitogen stimulation, which are retained within the cell using brefeldin A, has been of great value in the functional characterization of CD4+ T cells, including those derived directly from peripheral blood 22. Here, we describe a method that combines tetramer staining with measurement of the production of cytokines, chemokines, and perforin. This provides, for the first time, a means of examining the functional phenotype of circulating CD8+ T cells with specificity for a particular viral antigen at a single cell level. We use this technique to examine the secretion of a panel of soluble factors by CD8+ T cells responding to HIV and CMV antigens in HIV-infected subjects. The panel consisted of four soluble factors with different activities: (a) IFN-γ, known for inducing cellular antiviral proteins 23 and its ability to activate macrophages 24; (b) TNF-α, which is able to inhibit viral gene expression and replication 23; (c) macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1β, a chemokine that also suppresses HIV infection 25 through competition for the HIV coreceptor CC chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5); and (d) perforin, which promotes cell death through pore formation in the cell membrane 26. We show that the optimal method for stimulating the release of these factors is contact between the CD8+ T cells and their specific antigen. Using this technique, we show that the majority of tetramer-staining cells specific for both HIV and CMV antigens in HIV-infected patients are functionally active with regard to cytokine and chemokine secretion. However, HIV-specific CD8+ T cells are characterized by a striking lack of intracellular perforin staining, which is reflected in relatively poor ex vivo killing and correlates with persistent CD27 expression, a marker of cell differentiation. This apparent defect in cytolytic activity may contribute to the decline in CD8+-mediated suppression of HIV replication with disease progression.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects and Samples.

Samples were taken from HIV seronegative volunteers, and from HIV-infected subjects attending clinics in Oxford, London, San Diego, and New York who were largely selected on the basis of previous studies demonstrating a significant tetramer-staining CD8+ T cell population in their peripheral blood. These included patients taking highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and long-term survivors with good control of viral load in the absence of antiretroviral therapy. The local Institutional Review Boards approved this study. CD4+ T cell counts in the donors ranged between 200 and 1,200 cells/μl, and viral loads between <50 and 650,000 RNA copies/ml. HLA typing was carried out by amplification refractory mutation system (ARMS)-PCR using sequence-specific primers as described previously 27. PBMCs were separated from heparinized blood, and either studied fresh or cryopreserved for subsequent studies.

Generation of Antigen-specific CD8+ Clones.

Virus-specific CTL clones were generated from human PBLs by sorting using peptide–HLA monomer-coated beads as described previously 20 28. In brief, refolded biotinylated monomeric complexes were bound to streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (Dynal) at 4°C overnight. Beads were washed in cold RPMI 1640 (GIBCO BRL) and incubated with PBMCs at 10 beads per tetramer-positive cell (analyzed by FACS® beforehand) for 20 min at 4°C. After extensive washes, cells were plated in round-bottomed 96-well plates at 100 μl/well of the following cloning mixture: RPMI 1640, 10% human serum (HS), 107 irradiated PBMCs, PHA (5 μg/ml), and three to five sorted CTLs per milliliter. Cloning plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. After 4 d, Lymphocult-T (20%; Biotest) was added to the wells. After an additional 10 d of incubation, wells with substantial growth were expanded in 24-well plates using the cloning mixture described above. Clones were selected using cytotoxicity assay and tetramer staining. Selected clones were restimulated when proliferation reached a plateau (∼1 mo after cloning), by adding 2 × 106 irradiated PBMCs and PHA (at 5 μg/ml final concentration). Resting clones (with low CD69 expression level) were used for intracellular staining studies.

Antigens and Antibodies.

Peptides were synthesized by FMOC chemistry, and corresponded to defined CTL epitopes (see Table ). Anti-CD3 antibodies, OKT3, and anti-CD28 antibodies were purchased from Ortho and Becton Dickinson, respectively. Anti-CD8 (peridinin chlorophyll protein [PerCP]) and anti-CD69 (conjugated with FITC, PE, or allophycocyanin [APC]) antibodies were purchased from Becton Dickinson. Anti-CD25 (FITC), anti-CD27 (FITC), anti-CD28 (APC), anti-CD38 (APC), anti-CD45RO (APC), anti-CD45RA (FITC), anti–HLA-DR (FITC), and anti-Ki67 (FITC) antibodies were purchased from BD PharMingen. Anti–IFN-γ (FITC), anti–MIP-1β (FITC), and anti–TNF-α (FITC) mAbs were purchased from R&D Systems. Antiperforin (FITC) and anti–TNF-α (APC) mAbs were purchased from BD PharMingen and Becton Dickinson, respectively. Isotype control antibodies were purchased from Dako.

Table 1.

Peptides Corresponding to Defined CTL Epitopes

| HLA type specificity | Virus | Protein | Epitope | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A*0201 | HIV | Gag p17 | 77–85 | SLYNTVATL |

| A*0201 | HIV | Pol | 476–484 | ILKEPVHGV |

| A*0201 | CMV | Lower matrix protein pp65 | 495–503 | NLVPMVATV |

| A11 | HIV | Nef | 73–82 | QVPLRPMTYK |

| A*6802 | HIV | Pol | 744–752 | ETAYFILKL |

| B7 | HIV | Nef | 128–137 | TPGPGVRYPL |

| B7 | CMV | Lower matrix protein pp65 | 417–426 | TPRVTGGGAM |

| B8 | HIV | Nef | 89–97 | FLKEKGGL |

| B8 | HIV | Gag p24 | 259–267 | DIYKRWII |

| B*2705 | HIV | Gag p24 | 263–272 | KRWIIMGLNK |

| B57 | HIV | Gag p24 | 163–174 | KAFSPEVIPMF |

| B*5801 | HIV | Pol | 244–252 | IVLPEKDSW |

| Cw4 | HIV | Gag p17 | 28–36 | KYRLKHLVW |

A*6802/pol and Cw4/gag peptides are newly defined epitopes (Dong, T., unpublished data).

Preparation of HLA–Peptide Tetrameric Complexes.

The HLA molecule heavy chain cDNAs were modified by substitution of the transmembrane and cytosolic regions with a sequence encoding the BirA biotinylation enzyme recognition site, as described previously 8. These modified HLA heavy chains, and β2-microglobulin, were synthesized in a prokaryotic expression system (pET; R&D Systems), purified from bacterial inclusion bodies, and allowed to refold with the relevant peptide by dilution. Refolded monomeric complexes were purified by FPLC and biotinylated using BirA (Avidity), then combined with PE-labeled streptavidin (Sigma-Aldrich) at a 4:1 molar ratio to form tetrameric HLA–peptide complexes (hereafter “tetramers”). The list of tetramers used is given in Table . Tetramers were titrated against appropriate CTL clones to determine the dose that induced maximal staining 19.

Cell Surface and Intracellular Cytokine Staining.

Specific clones were incubated with one of the following: tetramers, OKT3 (Ortho) (coated onto the plate wells at 200 ng/ml for 2 h at 37°C beforehand), autologous B cell lines (BCL) pulsed with specific peptide at 20 μM, then washed before use (1:2 E/T ratio) or left untreated (negative control) in RPMI 1640/10% FCS. Studies were performed in the presence of brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml, and anti-CD28 antibody at 3 μg/ml. Freshly purified or thawed cryopreserved PBMCs were stained before activation with tetrameric complexes for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were subsequently incubated with specific antigens at 10 μM final concentration, or OKT3 at 100 ng/ml final concentration, or PBS (nonactivated cells), in RPMI 1640/10% FCS and in the presence of anti-CD28 antibody (at 3 μg/ml) and left for 6 h or overnight at 37°C. Brefeldin A (at 10 μg/ml final concentration) was added during the second hour of incubation. Nonactivated PBMCs were then stained with tetrameric complexes for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were washed in PBS, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1% BSA, fixed, and permeabilized in FACS™ Permeabilizing Buffer (Becton Dickinson) for 10 min. After washing, staining was performed for 15 min at room temperature in the dark using a panel of FITC-, PE-, PerCP-, or APC-conjugated antibodies. Cells were then washed and stored in 5% formaldehyde at 4°C until flow cytometry analysis was performed, using a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur™ machine. Four-color stainings were usually carried out on PBMC samples, using FITC-conjugated anti–IFN-γ, anti–TNF-α, anti–MIP-1β, or antiperforin antibodies to stain intracellular cytokines, PE-tetramers to stain antigen-specific CD8 T cells, PerCP-conjugated anti-CD8 to facilitate the analysis, and APC-conjugated anti-CD69 to assess cell activation, or APC-conjugated anti–TNF-α for double cytokine stainings. Isotype controls were carried out in each condition (activated or nonactivated) and were used to define limits for cytokine production. Perforin staining was generally carried out directly on whole blood. Specific tetramers were added to 100 μl of whole blood for 15 min at 37°C, the lymphocytes were then fixed, and the red blood cells were lysed using FACS™ Lysing Solution (Becton Dickinson). Permeabilization and staining using specific antibodies were carried out as above.

Fresh Cytotoxic Assay.

HLA-matched EBV-transformed autologous B cell lines were used as target cells in standard 51Cr-release CTL assays. 51Cr labeling was performed for 1 h, after which cells were pulsed for 1 h in the presence of specific peptides and extensively washed in RPMI medium. 5 × 103 target cells were aliquoted into microtiter plates. Controls included target cells incubated with medium or 10% Triton only. Freshly purified PBMCs were added to the targets at different E/T ratios, in triplicate. Partial depletion of the antigen-specific CD8+ T cells was carried out by staining the cells with the relevant tetramers, followed by MACS cell separation using anti-PE beads (Miltenyi Biotec). Assay plates were incubated 5 h before harvest. Specific 51Cr release was calculated from the following equation: [(experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release)] × 100%.

Results

Combination of Tetramer Staining and Intracellular Cytokine Staining

Tetramer Staining before Activation Permits Identification of the Tetramer-positive Population despite TCR Downregulation.

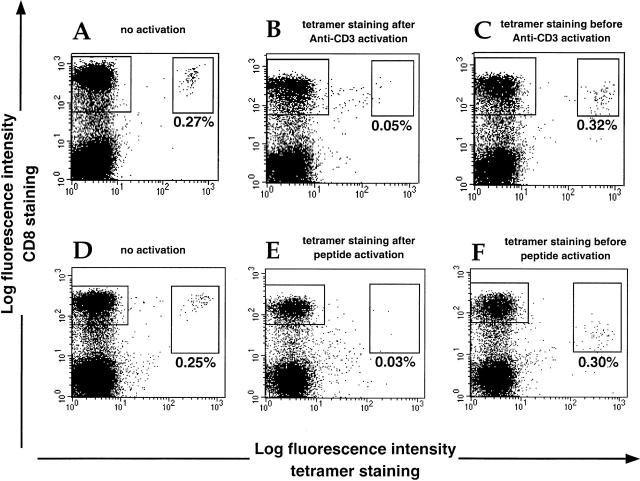

A potential hindrance to functional studies of tetramer-staining cells is that activation procedures needed to stimulate cytokine production will also lead to rapid downregulation of the TCR 29, with which the tetrameric complexes interact to stain antigen-specific T cells. This problem can be overcome by tetramer staining of the cells before activation. Fig. 1 shows the staining of PBMCs from a healthy CMV-positive HLA-B7 donor, in whom ∼1% of the CD8+ T cell population stains with an HLA-B7 CMV tetramer. PBMCs were incubated overnight in the presence of either OKT3 or the CMV B7-restricted epitope peptide. Significant downregulation of the TCR assessed by the level of tetramer staining was seen both in cells treated with OKT3 and, more dramatically, in the cells stimulated with peptide. However, cells stained with tetramers before activation maintained reasonable (although slightly reduced) levels of tetramer staining despite activation, probably due to tetramer internalization 30. A clear feature of the activated CD8+ T cells is partial downregulation of CD8, which is also most marked with peptide stimulation; this can be used as an indicator of activation. Similar data were obtained with donors of different HLA type and for CD8+ T cells of different specificity (HIV or CMV; data not shown).

Figure 1.

Tetramer staining and cell activation. PBMCs from a CMV-positive B7 donor were incubated for 12 h with brefeldin A in the presence of PBS (no activation control) (A and D), OKT3 (100 ng/ml) (B and C), or specific CMV B7 peptide (10 μM) (E and F). Tetramer staining was carried out either after overnight incubation (A, B, D, and E) or before addition of the activators (C and F). Percentages for tetramer-staining cells are shown. Cells were fixed and analyzed by flow cytometry after staining for CD8 surface molecules.

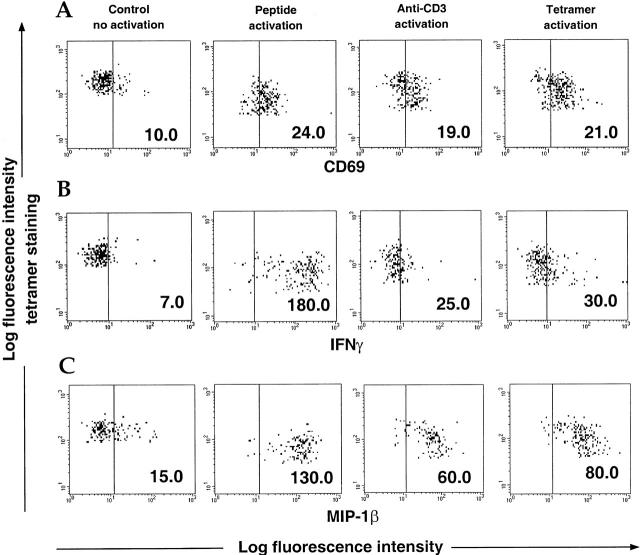

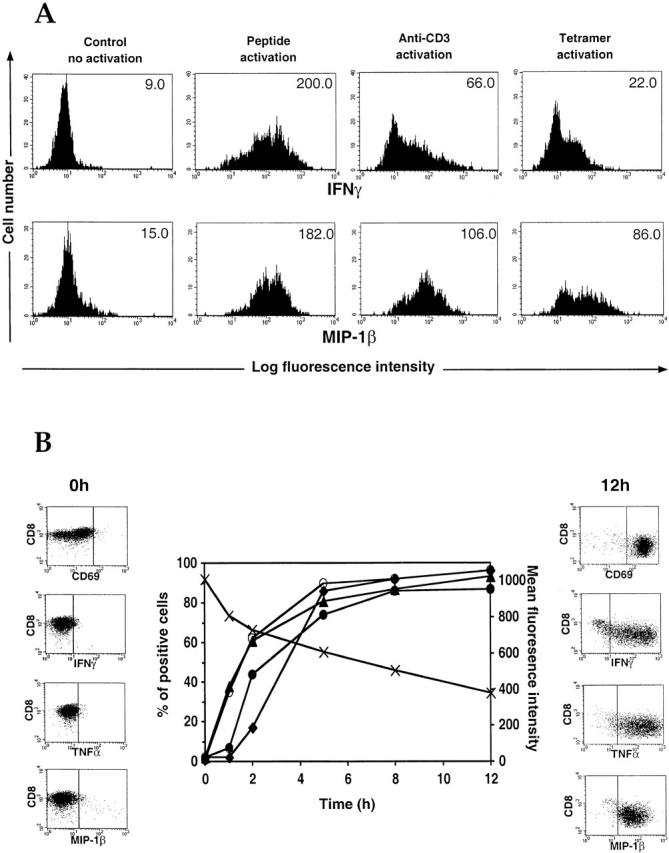

Specific Peptide Provides Optimal Activation.

Different methods of T cell activation were studied to determine the optimal protocol for intracellular cytokine staining. OKT3 is an antibody that activates T cells by binding to the CD3 molecule and cross-linking the TCR complex 31. Specific peptides are presented by the HLA molecules on APCs among the PBMC population to the TCRs of specific CD8+ T cells and induce activation. Since this interaction is reproduced when tetramers bind to the TCR-appropriate T cells, we examined whether they could directly influence T cell activation or interfere with activation of the cells induced by either peptide or OKT3. Fig. 2 A shows the extent of activation of the CMV B7 tetramer-staining population treated with tetramers alone or in combination with either OKT3 or peptide, using the early activation marker CD69. Similar levels of CD69 upregulation were observed using all three methods, confirming that tetramers can directly activate T cells. Whereas activation levels appeared to be identical, different profiles of IFN-γ and MIP-1β secretion were observed using intracellular staining. This was particularly striking for IFN-γ release, which was very low using OKT3 or tetramers, but maximal when triggered by specific peptide on APCs (Fig. 2 B). Compared with IFN-γ, higher levels of MIP-1β secretion were observed in response to OKT3 or tetramers, but were maximal if stimulated by the peptide-pulsed cells (Fig. 2 C). Thus, the optimal method of inducing cytokine release from antigen-specific CD8+ T cells appears to be the use of specific peptides. Similar results were obtained with PBMCs from different donors (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Comparison among peptide, OKT3, and tetramer activation. PBMCs from a CMV-positive B7 donor were incubated for 12 h with brefeldin A in the presence of PBS (no activation control), specific CMV B7 peptide (10 μM), OKT3 (100 ng/ml), or CMV B7 tetramers. Tetramer staining was carried out after overnight incubation for the no activation control or before addition of the activators for the “activated” cells. Cells were stained for CD69 (A), IFN-γ (B), and MIP-1β (C) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Data show cells gated on the CMV B7 tetramer-positive population. Mean fluorescence intensity is shown for each condition.

The Time Course of Cytokine and Chemokine Secretion by Individual Virus-specific CTL Clones.

The use of antigen-specific CTL clones remains a key element in the study of CTL function, although the physiological relevance of cells that have been propagated and restimulated for weeks in vitro may be questioned. We studied the intracellular staining profile of HIV-specific and CMV-specific CTL clones that had been generated and cultured for several weeks; intracellular cytokine studies were carried out at least 21 d after in vitro restimulation in order to study a resting cell population. These clones were assessed for IFN-γ and MIP-1β secretion after stimulation using peptide-pulsed APCs, OKT3 (coated onto culture wells), or specific tetramers (Fig. 3 A). The results were very similar to those using PBMCs, namely that although the clones displayed relatively similar levels of CD69 upregulation in response to all three activators (data not shown), cytokine expression, particularly IFN-γ, was much greater when stimulated by specific antigen presented by APCs.

Figure 3.

Intracellular staining in CTL clones. (A) A CMV-specific B7 clone was incubated for 12 h with brefeldin A in the presence of PBS (no activation control), specific antigen-pulsed APCs, OKT3 (coated onto the experimental wells), or CMV B7 tetramers. Intracellular staining for IFN-γ and MIP-1β was carried out, and the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Mean fluorescence intensity is shown for each condition. (B) An HIV-specific Cw4-restricted CTL clone was incubated for various times in the presence of brefeldin A and specific antigen-pulsed APCs. Cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD8 staining (x) is expressed in mean fluorescence intensity, and CD69 (○), IFN-γ (•), TNF-α (▴), and MIP-1β (♦) stainings are expressed in percentage of positive cells.

We then used the clones for time course experiments to identify the optimal time to measure cytokine and chemokine secretion after stimulation with antigen-pulsed APCs. As early as 1 h after activation, significant TNF-α staining could be detected, which closely followed the rise in CD69 expression (Fig. 3 B), whereas the production of IFN-γ and MIP-1β was relatively delayed. These factors were mainly generated during the first 5–6 h after activation, after which staining for both CD69 and intracellular cytokines reached a plateau. The increasing expression of the soluble factors was inversely proportional to the CD8 staining, which decreased over time after stimulation. Similar patterns of secretion were observed with other virus-specific clones (data not shown), and experiments using PBMCs showed low cytokine staining after 2 h but subsequently no differences between 6 h and overnight incubation (data not shown). Therefore, an incubation time of 6 h was chosen for subsequent assays.

We also examined the production of MIP-1α by the clones. The pattern of expression was similar to MIP-1β, although the staining intensity was very low: the poor efficiency of these antibodies for intracellular studies rendered them inadequate for use in PBMC studies (data not shown). Staining for RANTES was also assessed but led to inappropriate staining increase, assumed to be due to RANTES binding on the cell surface (data not shown). Therefore, we used MIP-1β staining to represent the CC chemokines that are able to suppress HIV replication 25.

HIV-specific CD8+ T Cells in Chronic HIV Infection Are Functionally Active for Cytokine Secretion

Most Tetramer-staining HIV-specific and CMV-specific CD8+ T Cells Express IFN-γ, MIP-1β, and TNF-α on Activation, but a Small Subpopulation Is TNF-α Negative.

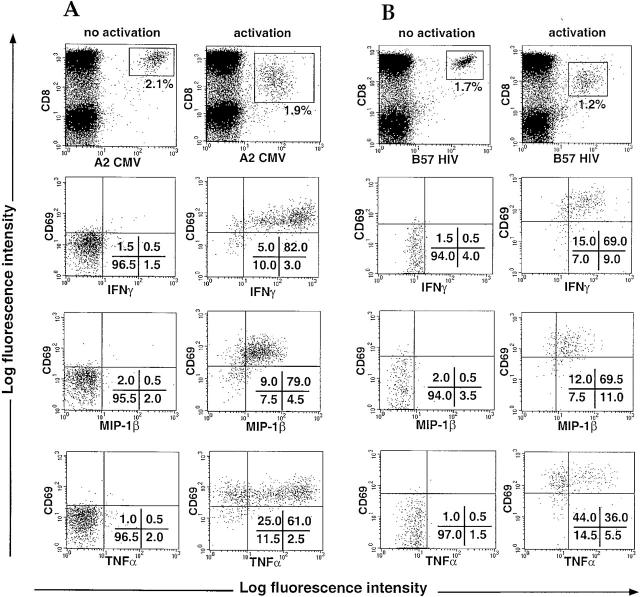

The optimized protocol for combined tetramer and intracellular cytokine staining described above was used to study the function of circulating CD8+ T cells specific for HIV and CMV. Fig. 4 shows representative results of intracellular staining for IFN-γ, MIP-1β, and TNF-α within the CMV (A) or HIV (B) specific CD8+ T cell population of two different donors. A slight decrease in the percentage of tetramer-positive cells was generally observed after stimulation. A small proportion of the activated T cells may not stain brightly enough to be gated among the tetramer-positive cells, or some cells may have presented antigen to one another and been lysed. However, the independent analysis of the tetramer staining data and cytokine staining data suggest that the gated tetramer-positive activated population is representative of the antigen-specific population as a whole. The cytokine expression profile is remarkably similar between the two viral specificities. After activation of the cells using specific antigens, the great majority of tetramer-staining cells displayed reduced levels of CD8 and TCR expression, and upregulation of CD69, indicating that most of the virus-specific population was adequately activated. 21 HIV-infected donors were studied, using the tetramers shown in Table (in total, 26 different tetramer-positive populations were studied). In most donors, between 50 and 95% of the activated virus-specific CD8+ T cells were producing IFN-γ and MIP-1β (Table ). Interestingly, although most of the antigen-specific CD8+ T cells secreted TNF-α in parallel with the other factors, a distinct subset of tetramer-staining cells was identified that failed to produce TNF-α even though they secreted IFN-γ and MIP-1β and had upregulated CD69. The size of the TNF-α–negative subpopulation varied between 0 and 60% in different tetramer-staining populations. Double cytokine stainings confirmed that these cells could still produce the other cytokines (data not shown). Overall, these results clearly demonstrate that, in chronically HIV-infected donors with a significant population of HIV-specific or CMV-specific tetramer-staining CD8+ cells, the majority of these cells produce a range of antiviral soluble factors in response to specific antigens. However, 2 of the 15 HIV-specific populations we analyzed (H9 and H14) showed much lower numbers of cytokine-secreting cells (∼25% of tetramer-positive cells). We are currently in the process of investigating these cells further to characterize their apparent defect in cytokine secretion.

Figure 4.

Intracellular staining for IFN-γ, MIP-1β, and TNF-α in HIV-specific or CMV-specific CD8+ T cells. PBMCs from HIV-infected patients were incubated for 6 h with brefeldin A in the presence of PBS (no activation) or specific peptides (10 μM) (activation). Intracellular staining for IFN-γ, MIP-1β, and TNF-α was carried out, and the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Cytokine staining is shown on CMV (A) and HIV (B) specific CD8+ T cell populations gated using the tetramers (top). Percentages of cells present in quadrants are shown. Representative data are shown (see Table ).

Table 2.

Cytokine Expression in Antigen-specific CD8 T Cells

| Percentage of positive cells | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor | Specificity | IFN-γ positive | MIP-1β positive | TNF-α positive |

| H1 | A2 gag | 72 | ND | 48 |

| H2 | A2 gag | 66 | ND | 29 |

| H3 | A2 gag | 86 | 75 | 47 |

| H4 | A2 gag | 86 | 85 | 25 |

| H5 | A2 gag | 98 | 86 | 90 |

| H6 | A2 gag | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| H7 | B8 gag | 88 | 80 | 71 |

| H8 | B8 nef | 78 | ND | ND |

| H9 | B8 nef | 25 | 40 | 20 |

| H10 | B8 nef | 80 | ND | ND |

| H11 | B8 nef | 60 | ND | 45 |

| H12 | B8 p24 | 60 | ND | 45 |

| H13 | B27 gag | 47 | 54 | 25 |

| H14 | B27 gag | 24 | 21 | 14 |

| H15 | B57 gag | 68 | 70 | 37 |

| C1 | A2 cmv | 66 | 62 | 49 |

| C2 | A2 cmv | 74 | 73 | 42 |

| C3 | A2 cmv | 55 | 53 | 39 |

| C4 | A2 cmv | 65 | 64 | 50 |

| C5 | A2 cmv | 83 | 83 | 60 |

| C6 | A2 cmv | 95 | 94 | 90 |

| C7 | B7 cmv | 95 | 95 | 95 |

| C8 | B7 cmv | 88 | 85 | 90 |

| C9 | B7 cmv | 76 | 73 | 56 |

| C10 | B7 cmv | 74 | 70 | 46 |

| C11 | B7 cmv | 88 | 80 | 60 |

Intracellular staining for IFN-γ, MIP-1β, and TNF-α was carried out in combination with tetramer staining using samples from HIV-infected patients. The table shows the cytokine expression in different antigen-specific CD8+ T cell populations stimulated with specific peptides.

The Cytokine Secretion of Antigen-specific CD8+ T Cells Is Not Affected by HAART.

A cross-sectional study was carried out using PBMC samples from eight HAART-treated HIV-infected patients. Several investigators have demonstrated that the frequency of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells usually declines to below detection after a few months on antiretroviral therapy 32 33 34 35. However, we could study CMV-specific CD8+ T cells in these subjects, since their numbers are maintained in HIV-infected subjects on antiretroviral therapy. Table shows the results of cytokine and chemokine production by CMV-specific CD8+ T cell populations from donors with either HLA-A2 or HLA-B7. Both the frequency and cytokine profile of the CMV-specific CD8+ T cells were unchanged in HAART-treated patients, and the proportion of TNF-α–negative tetramer-positive cells did not differ from untreated donors. We could also examine this question directly in four donors who had maintained populations of HIV-specific tetramer-staining cells in the range of 0.1–1.1% despite prolonged viral suppression on antiretroviral therapy (our unpublished data); cytokine release from these cells was in a similar range to that seen in most untreated donors. Taken together, these data suggest that HAART has no direct influence on the cytokine secretion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells.

Table 3.

Influence of HAART on CMV-specific CD8 T Cell Cytokine Expression

| Percentage of positive cells | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient (HLA type) | Months of treatment | Tetramer positive in CD8+ | IFN-γ positive | MIP-1β positive | TNF-α positive |

| 897 (A2) | 0 | 1.4 | 66 | 62 | 49 |

| 6 | 2.8 | 70 | 61 | 47 | |

| 10 | 2.4 | 74 | 65 | 50 | |

| 13 | 2.2 | 84 | 77 | 62 | |

| 912 (A2) | 0 | 1.5 | 74 | 73 | 42 |

| 6 | 1.2 | 81 | 71 | 50 | |

| 913 (A2) | 0 | 3.3 | 55 | 53 | 39 |

| 16 | 4 | 89 | 83 | 66 | |

| 1002 (A2) | 5 | 0.6 | 61 | 58 | 37 |

| 11 | 0.2 | 65 | 64 | 50 | |

| 17 | 0.3 | 63 | 64 | 50 | |

| 23 | 0.3 | 70 | 70 | 40 | |

| 31 | 0.5 | 73 | 65 | 45 | |

| 1003 (B7) | 12 | 2.3 | 76 | 73 | 56 |

| 31 | 3.5 | 75 | 60 | 67 | |

| 1010 (B7) | 4 | 3.3 | 74 | 70 | 46 |

| 17 | 3.4 | 74 | 70 | 54 | |

| 24 | 2.9 | 60 | 66 | 40 | |

| 31 | 3.5 | 67 | 68 | 45 | |

| 2002 (A2) | 5 | 5.5 | 83 | 83 | 60 |

| 17 | 6.4 | 80 | 78 | 58 | |

| 23 | 5 | 79 | 87 | 55 | |

| 29 | 8 | 89 | ND | 71 | |

| 2003 (B7) | 11 | 5.6 | 77 | 80 | 28 |

| 21 | 5.8 | 88 | 78 | 60 | |

Intracellular staining for IFN-γ, MIP-1β, and TNF-α was carried out in combination with tetramer staining using samples from HAART-treated HIV-infected patients. The table shows the cytokine expression and tetramer numbers in CMV-specific CD8+ T cells stimulated with specific peptides.

HIV-specific CD8+ T Cells Appear to Be at a Different Stage of Maturation from CMV-specific CD8+ T Cells

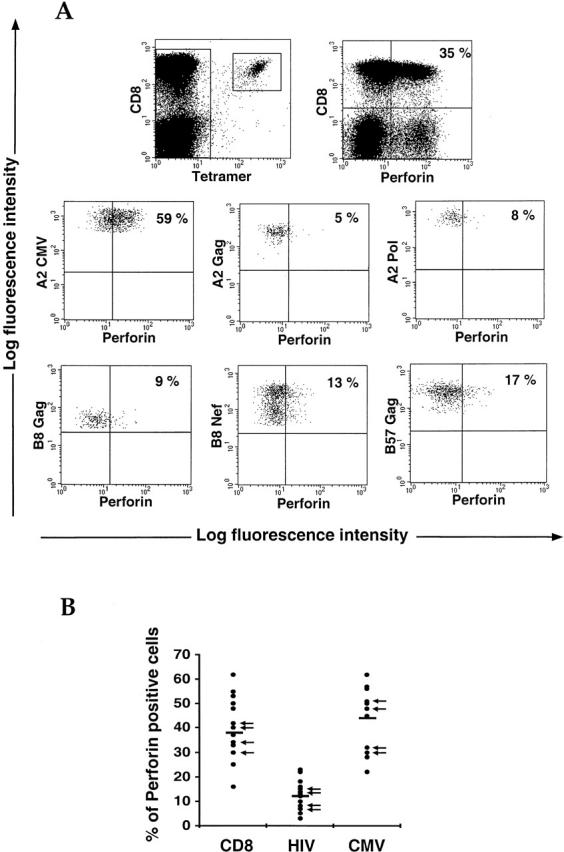

HIV-specific CD8+ T Cells Express Low Levels of Perforin.

We then studied the expression of perforin, which is intimately linked with cytolytic activity in virus-specific CD8+ T cells 26 36. In contrast to the other factors studied, perforin staining does not require any activation before the cells are permeabilized, implying that there are stores of preformed perforin in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Indeed, perforin staining was often reduced after T cell activation of CTL clones or in PBMCs (data not shown), presumably due to release of the preformed perforin. 18 samples from chronically HIV-infected patients were costained with HIV and/or CMV tetramers and antibodies to perforin. Fig. 5 A shows a representative perforin staining obtained with PBMCs from a single donor who had significant numbers of both HIV-specific and CMV-specific CD8+ T cell populations. A striking observation was that the expression of perforin in HIV-specific CD8+ T cells was much lower than that detected in either the CMV-specific CD8+ T cells or the CD8+ population as a whole. Several antigen-specific CD8+ T cell populations from different donors (A2 Gag, A2 Pol, A11 Nef, B7 Nef, B8 Gag, B8 Nef, B8 p24, B27 Gag, B57 Gag, and B58 Pol for HIV, and A2 and B7 for CMV) were stained for perforin to compare perforin levels in HIV-specific, CMV-specific, and total CD8+ T cells (Fig. 5 B). This confirmed that HIV-specific CD8+ T cells are unusually low in perforin compared with CMV-specific CD8+ T cells, which more closely resemble the rest of the CD8+ T cell population.

Figure 5.

Perforin staining in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. (A) Perforin intracellular staining was carried out in a sample from an HIV-infected patient known to have both HIV-specific and CMV-specific CD8+ T cell populations. Cells were stained with tetramers and directly stained for perforin without cell activation. Both the total lymphocyte population (top row) and the antigen-specific CD8+ T cells (bottom rows) were gated and analyzed for perforin staining. The data are expressed as percentages of perforin-positive cells determined to be staining above the horizontal limit. Similar observations were obtained with other donors who also had both HIV-specific and CMV-specific CD8+ T cell populations. (B) Perforin intracellular staining was performed, as above, in samples known to have either an HIV-specific or a CMV-specific CD8 T cell population. Data are expressed in numbers of perforin-positive cells within the relevant cell populations. 18, 18, and 13 samples are displayed for whole, HIV-specific, and CMV-specific CD8+ T cell populations, respectively. Arrows indicate that samples come from HAART-treated donors.

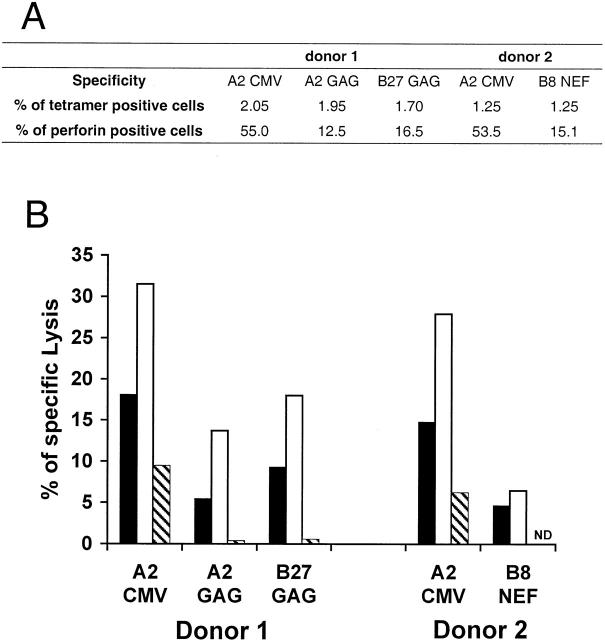

HIV-specific Killing Ex Vivo Is Lower Than CMV-specific Lysis from the Same Donor.

The lack of perforin in HIV-specific populations was correlated with decreased cytotoxic activity compared with CMV-specific populations. Ex vivo cytotoxic assays were carried out in two donors possessing similar percentages of both HIV (A2 Gag, B27 Gag, and B8 Nef) and CMV (A2 CMV) tetramer-staining cells (Fig. 6 A). In each case, the HIV-specific populations showed lower levels of specific lysis compared with CMV-specific CD8+ T cells at the same E/T ratios, which approximately corresponded to the proportions of perforin in each population. HIV-specific CD8+ T cells therefore appear to be less efficient cytotoxic effectors. Depletion of the tetramer-staining populations caused a significant reduction of specific killing (Fig. 6 B), showing that the cytotoxicity observed is largely due to the presence of the antigen-specific CD8+ T cells.

Figure 6.

Fresh cytotoxic assay with HIV-specific or CMV-specific CD8+ T cells from the same donors. (A) Cell frequency and percentage of HIV-specific or CMV-specific CD8+ T cells expressing perforin from each donor. (B) Specific lysis obtained with the relevant HIV-specific or CMV-specific populations. Freshly isolated PBMCs were incubated for 5 h with targets pulsed with specific peptide or no peptide at different E/T ratios: 100:1 (black bars), 200:1 (white bars), or 100:1 after partial depletion of the tetramer-positive cells (hatched bars).

If low perforin levels in vivo are due to constant degranulation in response to persistent viral antigens, then patients with prolonged viral suppression after optimal antiretroviral therapy would be expected to have restored perforin levels. However, we were able to examine the perforin staining of HIV-specific tetramer-staining populations in three donors with undetectable viral loads for at least 4 yr on therapy (our unpublished data), and this was in the range of 3–19% (Fig. 5 B, arrows). This observation makes it unlikely that repeated degranulation underlies the perforin defect we have described.

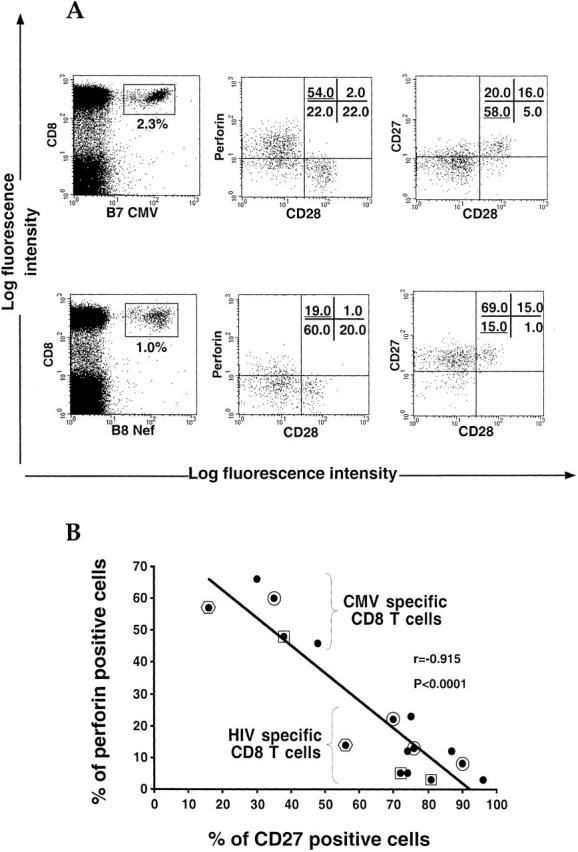

Difference in the Expression of Maturation Markers between CMV-specific and HIV-specific CD8+ T Cells.

To characterize further the differences between HIV-specific and CMV-specific CD8+ T cells, we used cell surface markers to assess their phenotype ex vivo. We found no obvious differences in their activation status, assessed by the expression of CD69 (negative), CD25 (negative), HLA-DR (positive), and CD38 (mixed population) (data not shown). Neither of these populations was proliferating, as measured by general lack of Ki67 expression (data not shown). The state of cell maturation was assessed using the markers CD28, CD27, CD45RO, and CD45RA. The majority of HIV-specific and CMV-specific CD8+ T cells were negative for CD28 (Fig. 7 A), which has been shown to be downregulated on effector cells 37. Perforin-producing cells were found among this population, as expected from previous studies 38. However, CD27 expression differed between HIV-specific and CMV-specific CD8+ T cells, as HIV-specific CD8+ T cells were predominantly CD27+ compared with CMV-specific CD8+ T cells, which were mainly CD27−. HIV-specific CD8+ T cells were generally CD45RA−RO+ as described previously 32, but some CMV-specific CD8+ T cells expressed CD45RA (data not shown). There was a strong inverse correlation between perforin expression and CD27 expression, even when comparing HIV-specific and CMV-specific populations from the same donors, implying that perforin-producing cells are CD27− (Fig. 7 B). CMV-specific CD8+ T cells therefore appear to be fully mature effector cells, as they are both CD27− and CD28−, and express perforin 37. In contrast, HIV-specific CD8+ T cells have not reached the same stage of maturation as the CMV effectors, as they retain CD27 and show low perforin expression.

Figure 7.

Comparison between CMV-specific and HIV-specific CD8+ T cells for perforin and maturation markers. (A) Stainings for perforin, CD28, and CD27 were performed in CMV (B7 CMV) or HIV (B8 Nef) specific CD8+ T cell populations gated by means of specific tetramers. Percentages of cells present in quadrants are shown. Data are representative of 15 different stainings. (B) Inverse correlation between perforin and CD27 staining in HIV-specific and CMV-specific CD8+ T cells. Each dot represents perforin and CD27 staining for a single antigen-specific CD8+ T cell population. Framed dots (circle, square, or hexagon) show specific populations belonging to the same donor.

Discussion

The technique we have described combines the advantages provided by the tetramer technology of reliable identification and quantification of T cells of known specificity together with information about their functional capacity through intracytoplasmic staining for cytokines and chemokines. This method has the potential to provide valuable information about antigen-specific T cells in a range of conditions.

Specific antigens provided the best way to stimulate cytokine secretion, and represent a more physiological activation method than PMA and ionomycin, commonly used in intracellular cytokine staining studies; a recent report has emphasized the difference between these compounds and specific antigens, since they induce different pathways of cytotoxity in CD8+ T cells 39. We were able to bypass the problem of TCR downregulation upon T cell activation by staining the cells with tetramers before stimulation. This preserves the staining of the tetramer-positive population so that their cytokine production can be measured. Even though activation-induced TCR downregulation probably still occurs, the fluorescent signal of internalized tetramers can nevertheless be recorded. It has recently been shown using confocal microscopy that tetramer internalization can be detected within 15 min of incubation with a virus-specific T cell clone at 37°C 30.

Although the best method of stimulation is to use APCs pulsed with specific peptide, it was striking that on their own tetramers can activate antigen-specific CD8+ T cells to produce cytokines, and did so as efficiently as PHA or OKT3. It is theoretically possible that some activation might result from free peptide released by tetramers that have spontaneously dissociated. Although other methods of stimulation led to upregulation of CD69 and moderate MIP-1β production, only antigen-pulsed APCs led to secretion of both MIP-1β and IFN-γ by the majority of tetramer-positive cells. It is likely that other interactions between the APCs and CD8+ T cells, such as adhesion and costimulatory molecules, contribute to better stimulation of cytokine release. The downregulation of CD8 was a consistent feature of these activated T cells, and correlated closely with the degree of activation and induced cytokine release. It is intriguing that MIP-1β secretion was more readily induced by suboptimal stimuli than IFN-γ, which highlights the potential for differential regulation of cytokine secretion in antigen-specific T cells. This observation emphasizes the complexity of the machinery and regulation of T cell activation.

Using CTL clones to optimize our methodology, we observed that the first cytokine released was TNF-α. This is consistent with a recent study which demonstrated the presence of preformed TNF-α mRNA in LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells 40. The kinetics of production of MIP-1β and IFN-γ were remarkably similar; moreover, all tetramer-positive cells that produced MIP-1β also secreted IFN-γ and vice versa. MIP-1β therefore seems to show the same secretion pattern as IFN-γ, even though previous studies have suggested that it is stored in cytolytic granules complexed with sulfated proteoglycans, along with granzyme A, RANTES, and MIP-1α 41. These data also provide support for the use of ELISPOT assays that measure IFN-γ in response to specific antigen to detect the main population of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells 5. In contrast, a significant population of tetramer-staining cells produced IFN-γ and MIP-1β but not TNF-α; this shows that different functional subsets of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells may exist. It has so far not been possible to characterize the TNF-α–negative population further in terms of specific surface markers. These functional studies of tetramer-staining cells provide a better method to study the potential diversity among T cells responding to a particular antigen than individual T cell clones, since these may not be representative of the total responding T cell population, which is likely to include cells that are unable to survive and proliferate in tissue culture conditions 42.

These data provide the first clear evidence of the functional capacity, with regard to cytokine secretion, of circulating CD8+ T cells specific for HIV and CMV antigens. This is particularly relevant for the HIV-specific population, as it has been proposed that these cells may be functionally defective in HIV-infected individuals as a consequence of inadequate CD4+ T cell help 16. In a murine model of LCMV infection in animals lacking CD4, CD8+ T cells elicited on LCMV challenge could be detected by tetramer staining but lacked effector functions, including cytolysis and IFN-γ secretion, and failed to mediate viral clearance 15. More recently, a population of CD8+ T cells was identified in a patient with metastatic melanoma, which stained with tetrameric complexes of HLA-A2 and a melanoma peptide but failed to lyse melanoma target cells or secrete cytokines after mitogen stimulation 17. In contrast, our studies show that the majority of HIV-specific and CMV-specific CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood are able to produce a range of potent antiviral factors after stimulation with specific antigen. In particular, this includes factors such as MIP-1β and IFN-γ that are known to have the capacity to inhibit HIV replication 25 43. This means that HIV-specific T cells should be producing these factors at sites of HIV replication in specific response to viral antigens. All of the HIV-infected subjects studied were selected on the basis of a previously identified population of tetramer-positive cells: the majority were in the asymptomatic phase of chronic infection. It is plausible that in the late stages of disease, when CD4+ T cell help is even more limited, the cytokine secretion of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells could be less efficient, as seen in two of our donors, H9 and H14. However, because of the requirement to be able to identify a substantial tetramer-staining cell population in order to carry out this kind of analysis, we have not yet been able to study patients with progressive HIV infection. Recent studies of HIV-infected subjects with chronic HIV infection, using a flow cytometric assay of IFN-γ production in response to HIV antigens, have demonstrated that HIV-specific CD4+ T cell responses are more readily detected than could be measured previously using standard proliferation assays 44.

Although the cytokine secretion profile of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells is similar to that of CD8+ T cells responding to CMV, a striking difference is that the HIV-specific population expresses very little perforin. This is consistent with a previous study showing that CD8+ T cells infiltrating lymphoid tissue in HIV-infected individuals have impaired perforin expression 45.

We considered whether chronic stimulation of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells in the infected patient could result in low perforin levels as a consequence of repeated contact with virus-infected cells and subsequent degranulation. However, there were no significant differences in the expression of the markers for either early or late activation between HIV-specific and CMV-specific CD8+ T cells. Furthermore even in treated patients with optimal viral suppression on antiretroviral therapy, there was no restoration of perforin levels in the HIV-specific CD8+ population, nor did perforin expression increase in HIV-specific CD8+ T cells cultured in vitro in the presence of IL-2 (data not shown).

Therefore, it is likely that HIV-specific CD8+ T cells are genuinely defective in perforin production, which could render them less efficient at killing virus-infected cells. We found that the degree of HIV-specific ex vivo lysis was much lower than direct killing from CMV-specific cells in the same donor, although the tetramer-positive populations were of similar sizes. The observed correlation between ex vivo lysis mediated by HIV-specific CD8+ T cells and tetramer staining 18 confirms that HIV-specific cells maintain some degree of lytic potential. However, the levels of lysis elicited in this study 18 were relatively low (no more than 5–10% specific lysis) for the numbers of tetramer-positive cells, and several patients had levels of A2 gag tetramer staining of between 1 and 5% with no detectable ex vivo lysis whatsoever. In contrast, the levels of ex vivo killing by CMV-specific CD8+ T cells isolated directly from peripheral blood are much higher (up to 40–50% specific lysis) 17 46. Although cytotoxicity mediated through Fas–FasL interactions is an alternative route of target cell lysis, a recent study has shown that virus-specific CTL clones lyse HIV-infected T lymphocytes by means of the granule exocytosis pathway 39, which is consistent with our observations using HIV-specific CTL clones (Appay, V., and T. Dong, unpublished). The preservation of perforin staining and functional activity in the CMV-specific CD8+ T cells of HIV-infected donors argues strongly against a generalized defect in perforin production in HIV infection.

The phenotype of the HIV-specific CD8+ T cell population we have described suggests that they may be immature effector cells, with a pattern of maturation markers that lie in between those previously defined for memory and effector cells 37. This observation is in contrast to our findings for CMV-specific CD8+ T cells, which display a fully mature effector phenotype 37. The main difference is the persistent expression of CD27, a molecule from the TNF receptor superfamily 47 that is expressed on thymic emigrants and upregulated on antigen-primed cells, but is not usually expressed on differentiated effector cells 48. It is possible that these cells are arrested in an immature and functionally impaired stage of maturation due to a lack of CD4+ T cell help, as has recently been suggested 16. As the initial loss of CD4+ T cell help is specific for HIV antigens 49, CMV-specific CD8+ T cells would be unaffected in early HIV disease and would therefore resemble the CMV-specific CD8+ T cell population seen in HIV-uninfected donors.

In conclusion, HIV-specific CD8+ T cells are functional with regard to antiviral cytokine production in the asymptomatic phase of HIV infection, and therefore could contribute to the control of HIV replication to a certain extent. However, the defect in cytolytic function of these T cells, which are apparently unable to mature into genuine cytotoxic effector cells, could render them unable to eliminate the virus. A better understanding of the mechanism underlying this apparent block to the maturation of true HIV-specific effector CD8+ T cells could facilitate the suppression and potentially even the clearance of the virus.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues Anthony Kelleher, Pokrath Hansasuta, and Jennifer Hu for their help and support. We are very grateful to the staff and patients of the clinics that provided blood samples, particularly the John Warin Ward at the Churchill Hospital, Oxford, the Caldecot Centre at King's College Hospital London, and the Veterans Administration Research Center for AIDS and HIV Infection and the University of California at San Diego Center for AIDS Research.

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom, the Elizabeth Glaser Paediatric AIDS Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health. S.L. Rowland-Jones is a Medical Research Council Senior Fellow and holds an Elizabeth Glaser scientist award. D.F. Nixon is supported by a National Institutes of Health grant (R01 AI44595) and holds an Elizabeth Glaser scientist award. H.M.L. Spiegel is an Elizabeth Glaser scholar of the Paediatric AIDS Foundation.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: APC, allophycocyanin; ELISPOT, enzyme-linked immunospot; HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; LDA, limiting dilution assay; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; PerCP, peridinin chlorophyll protein; RANTES, regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted.

References

- Carmichael A., Jin X., Sissons P., Borysiewicz L. Quantitative analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)–specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) response at different stages of HIV-1 infectiondifferential CTL responses to HIV-1 and Epstein-Barr virus in late disease. J. Exp. Med. 1993;177:249–256. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalams S.A., Johnson R.P., Trocha A.K., Dynan M.J., Ngo S., D'Aquila R.T., Kurnick J.T., Walker B.D. Longitudinal analysis of T cell receptor (TCR) gene usage by human immunodeficiency virus 1 envelope–specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte clones reveals a limited TCR repertoire. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:1261–1271. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss P.A.H., Rowland-Jones S.L., Frodsham P.M., McAdam S., Giangrande P., McMichael A.J., Bell J.I. Persistent high frequency of human immunodeficiency virus-specific cytotoxic T cells in peripheral blood of infected donors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:5773–5777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern F., Surel I.P., Brock C., Freistedt B., Radtke H., Scheffold A., Blasczyk R., Reinke P., Schneider-Mergener J., Radbruch A. T-cell epitope mapping by flow cytometry. Nat. Med. 1998;4:975–978. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalvani A., Brookes R., Hambleton S., Britton W.J., Hill A.V., McMichael A.J. Rapid effector function in CD8+ memory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:859–865. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murali-Krishna K., Altman J.D., Suresh M., Sourdive D.J., Zajac A.J., Miller J.D., Slansky J., Ahmed R. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cellsa re-evaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity. 1998;8:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan L.C., Gudgeon N., Annels N.E., Hansasuta P., O'Callaghan C.A., Rowland-Jones S., McMichael A.J., Rickinson A.B., Callan M.F. A re-evaluation of the frequency of CD8+ T cells specific for EBV in healthy virus carriers. J. Immunol. 1999;162:1827–1835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J., Moss P.A.H., Goulder P., Barouch D., McHeyzer-Williams M., Bell J.I., McMichael A.J., Davis M.M. Direct visualization and phenotypic analysis of virus-specific T lymphocytes in HIV-infected individuals. Science. 1996;274:94–96. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callan M.F., Tan L., Annels N., Ogg G.S., Wilson J.D., O'Callaghan C.A., Steven N., McMichael A.J., Rickinson A.B. Direct visualization of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during the primary immune response to Epstein-Barr virus in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:1395–1402. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan R., Xu X., Ogg G.S., Hansasuta P., Dong T., Rostron T., Luzzi G., Conlon C.P., Screaton G.R., McMichael A.J., Rowland-Jones S. Rapid death of adoptively transferred T cells in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Blood. 1999;93:1506–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J.D.K., Ogg G.S., Allen R.L., Goulder P.J.R., Kelleher A., Sewell A.K., O'Callaghan C.A., Rowland-Jones S.L., Callan M.F.C., McMichael A.J. Oligoclonal expansions of CD8+ T cells in chronic HIV infection are antigen specific. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:785–790. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.4.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris A.G., Lin Y.-L., Askonas B.A. Immune interferon release when a cloned cytotoxic T cell meets its correct influenza-infected target cell. Nature. 1982;295:150–152. doi: 10.1038/295150a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jassoy C., Harrer T., Rosenthal T., Navia B.A., Worth J., Johnson R.P., Walker B.D. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes release gamma interferon, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), and TNF-beta when they encounter their target antigens. J. Virol. 1993;67:2844–2852. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.5.2844-2852.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallimore A., Glithero A., Godkin A., Tissot A.C., Pluckthun A., Elliott T., Hengartner H., Zinkernagel R. Induction and exhaustion of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus–specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes visualized using soluble tetrameric major histocompatibility complex class I–peptide complexes. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:1383–1393. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajac A.J., Blattman J.N., Murali-Krishna K., Sourdive D.J., Suresh M., Altman J.D., Ahmed R. Viral immune evasion due to persistence of activated T cells without effector function. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:2205–2213. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalams S.A., Walker B.D. The critical need for CD4 help in maintaining effective cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:2199–2204. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P.P., Yee C., Savage P.A., Fong L., Brockstedt D., Weber J.S., Johnson D., Swetter S., Thompson J., Greenberg P.D. Characterization of circulating T cells specific for tumor-associated antigens in melanoma patients. Nat. Med. 1999;5:677–685. doi: 10.1038/9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg G.S., Xin J., Bonhoeffer S., Dunbar P.R., Nowak M.A., Monard S., Segal J.P., Cao Y., Rowland-Jones S.L., Cerundolo V. Quantitation of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and plasma viral RNA load. Science. 1998;279:2103–2106. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5359.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar P.R., Ogg G.S., Chen J., Rust N., van der Bruggen P., Cerundolo V. Direct isolation, phenotyping and cloning of low-frequency antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes from peripheral blood. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:413–416. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar P.R., Chen J.L., Chao D., Rust N., Teisserenc H., Ogg G.S., Romero P., Weynants P., Cerundolo V. Cutting edgerapid cloning of tumor-specific CTL suitable for adoptive immunotherapy of melanoma. J. Immunol. 1999;162:6959–6962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerici M., Shearer G. A TH1-->TH2 switch is a critical step in the etiology of HIV infection. Immunol. Today. 1993;14:107–111. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Openshaw P., Murphy E.E., Hosken N.A., Maino V., Davis K., Murphy K., O'Garra A. Heterogeneity of intracellular cytokine synthesis at the single-cell level in polarized Th1 and Th2 populations. J. Exp. Med. 1995;182:1357–1362. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti L.G., Chisari F.V. To kill or to cureoptions in host defense against viral infection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1996;8:478–483. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton E.T., Matsumoto-Kobayashi M., Perussia B., Trinchieri G. Role of immune interferon in the monocytic differentiation of human promyelocytic cell lines induced by leukocyte conditioned medium. Blood. 1985;66:583–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocchi F., DeVico A.L., Garzino D.A., Arya S.K., Gallo R.C., Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1 alpha, and MIP-1 beta as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270:1811–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.C., Walsh C.M., Young J.D. Perforinstructure and function. Immunol. Today. 1995;16:194–201. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunce M., O'Neill C.M., Barnardo M.C., Krausa P., Browning M.J., Morris P.J., Welsh K.I. Phototypingcomprehensive DNA typing for HLA-A, B, C, DRB1, DRB3, DRB4, DRB5 & DQB1 by PCR with 144 primer mixes utilizing sequence-specific primers (PCR-SSP) Tissue Antigens. 1995;46:355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1995.tb03127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg G.S., King A.S., Dunbar P.R., McMichael A.J. Isolation of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes using human leukocyte antigen-coated beads. AIDS. 1999;13:1991–1993. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199910010-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valitutti S., Muller S., Dessing M., Lanzavecchia A. Different responses are elicited in cytotoxic T lymphocytes by different levels of T cell receptor occupancy. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:1917–1921. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan J.A., Dunbar P.R., Price D.A., Purbhoo M.A., Lechner F., Ogg G.S., Griffiths G., Phillips R.E., Cerundolo V., Sewell A.K. Specificity of CTL interactions with peptide-MHC class I tetrameric complexes is temperature dependent. J. Immunol. 1999;163:4342–4348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoukas C.D., Landgraf B., Bentin J., Valentine M., Lotz M., Vaughan J.H., Carson D.A. Activation of resting T lymphocytes by anti-CD3 (T3) antibodies in the absence of monocytes. J. Immunol. 1985;135:1719–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg G.S., Jin X., Bonhoeffer S., Moss P., Nowak M.A., Monard S., Segal J.P., Cao Y., Rowland-Jones S.L., Hurley A. Decay kinetics of human immunodeficiency virus-specific effector cytotoxic T lymphocytes after combination antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 1999;73:797–800. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.797-800.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray C.M., Lawrence J., Schapiro J.M., Altman J.D., Winters M.A., Crompton M., Loi M., Kundu S.K., Davis M.M., Merigan T.C. Frequency of class I HLA-restricted anti-HIV CD8+ T cells in individuals receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) J. Immunol. 1999;162:1780–1788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalams S.A., Goulder P.J., Shea A.K., Jones N.G., Trocha A.K., Ogg G.S., Walker B.D. Levels of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte effector and memory responses decline after suppression of viremia with highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Virol. 1999;73:6721–6728. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6721-6728.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz G.M., Nixon D.F., Trkola A., Binley J., Jin X., Bonhoeffer S., Kuebler P.J., Donahoe S.M., Demoitie M.A., Kakimoto W.M. HIV-1–specific immune responses in subjects who temporarily contain virus replication after discontinuation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:R13–R18. doi: 10.1172/JCI7371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagi D., Ledermann B., Burki K., Seiler P., Odermatt B., Olsen K.J., Podack E.R., Zinkernagel R.M., Hengartner H. Cytotoxicity mediated by T cells and natural killer cells is greatly impaired in perforin-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;369:31–37. doi: 10.1038/369031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann D., Baars P.A., Rep M.H., Hooibrink B., Kerkhof-Garde S.R., Klein M.R., van Lier R.A. Phenotypic and functional separation of memory and effector human CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:1407–1418. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posnett D.N., Edinger J.W., Manavalan J.S., Irwin C., Marodon G. Differentiation of human CD8 T cellsimplications for in vivo persistence of CD8+ CD28− cytotoxic effector clones. Int. Immunol. 1999;11:229–241. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar P., Xu Z., Lieberman J. Viral-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes lyse human immunodeficiency virus-infected primary T lymphocytes by the granule exocytosis pathway. Blood. 1999;94:3084–3093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slifka M.K., Rodriguez F., Whitton J.L. Rapid on/off cycling of cytokine production by virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Nature. 1999;401:76–79. doi: 10.1038/43454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner L., Yang O.O., Garcia-Zepeda E.A., Ge Y., Kalams S.A., Walker B.D., Pasternack M.S., Luster A.D. Beta-chemokines are released from HIV-1-specific cytolytic T-cell granules complexed to proteoglycans. Nature. 1998;391:908–911. doi: 10.1038/36129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotch F.M., Nixon D.F., Alp N., McMichael A.J., Borysiewicz L.K. High frequency of memory and effector gag specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in HIV seropositive individuals. Int. Immunol. 1990;2:707–712. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.8.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emilie D., Maillot M.C., Nicolas J.F., Fior R., Galanaud P. Antagonistic effect of interferon-gamma on tat-induced transactivation of HIV long terminal repeat. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:20565–20570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher C.J., Quittner C., Peterson D.M., Connors M., Koup R.A., Maino V.C., Picker L.J. HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cells are detectable in most individuals with active HIV-1 infection, but decline with prolonged viral suppression. Nat. Med. 1999;5:518–525. doi: 10.1038/8400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson J., Behbahani H., Lieberman J., Connick E., Landay A., Patterson B., Sonnerborg A., Lore K., Uccini S., Fehniger T.E. Perforin is not co-expressed with granzyme A within cytotoxic granules in CD8 T lymphocytes present in lymphoid tissue during chronic HIV infection. AIDS. 1999;13:1295–1303. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199907300-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie G.M.A., Wills M.R., Appay V., O'Callaghan C., Murphy M., Smith N., Sissons P., Rowland-Jones S., Bell J.I., Moss P.A.H. Functional heterogeneity and high frequencies of CMV-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in healthy seropositive donors. J. Virol. 2000;In press doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.17.8140-8150.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lier R.A., Borst J., Vroom T.M., Klein H., Van Mourik P., Zeijlemaker W.P., Melief C.J. Tissue distribution and biochemical and functional properties of Tp55 (CD27), a novel T cell differentiation antigen. J. Immunol. 1987;139:1589–1596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hintzen R.Q., de Jong R., Lens S.M., van Lier R.A. CD27marker and mediator of T-cell activation? Immunol. Today. 1994;15:307–311. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musey L.K., Kreiger J.N., Hughes J.P., Schacker T.W., Corey L., McElrath M.J. Early and persistent human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific T helper dysfunction in blood and lymph nodes following acute HIV-1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 1999;180:278–284. doi: 10.1086/314868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]