Abstract

Hormone-refractory prostate cancer is a disease that includes a variety of patients and represents a treatment dilemma for the practicing physician. Because of the diversity of this group, management strategies must be targeted to the clinical situations of the individual patients and their wishes. This article outlines a logical progression of treatment choices that currently exist in this rapidly evolving field, and the landmark chemotherapy trials involving docetaxel (SWOG 9916 and TAX 327) are reviewed. Although significant progress has been made in understanding and treating hormone-refractory prostate cancer, current treatments do not yet provide a cure, and important clinical trials continue to recruit patients.

Key words: Androgen-independent prostate cancer, Chemotherapy, Prostate cancer, Taxanes, Hormone-refractory prostate cancer, Metastatic prostate cancer

Androgen-independent prostate cancer is a disease that included a varied group of patients. Historically, despite castrate levels of testosterone, patients with metastatic disease typically manifested disease progression within 12 to 18 months with a median survival of 2 to 3 years.1 The introduction of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) into clinical practice in the 1980s led to new insights into the development of hormone resistance. A new subset of patients with or without clinical metastases, who, after being managed by androgen deprivation, were discovered to have an increasing PSA in the absence of obvious clinical disease progression, thus becoming “hormone refractory” at an earlier state of the disease continuum. These patients may in fact have a very different disease course. Oefelein and colleagues2 recently demonstrated that this reported range of survival was not consistent with current clinical presentations. They reported that the median survival after the development of hormone-refractory disease was approximately 40 months in the patients with evidence of skeletal metastasis and 68 months in those without skeletal metastasis.2 In spite of intensive research efforts, the molecular mechanisms by which prostate cancer cells become resistant to hormone therapy remain poorly characterized.3,4

Actually classifying these patients can be confusing. Patients who have castrate levels of testosterone and are no longer responsive to hormonal manipulations are by definition “androgen independent.” Many current clinical trials for patients with advanced prostate cancer, however, include patients who do not have any additional hormonal manipulations. In the broadest sense, patients with hormone-refractory cancer include all those with PSA and/or clinical progression while on hormonal therapy and with castrate levels of testosterone.

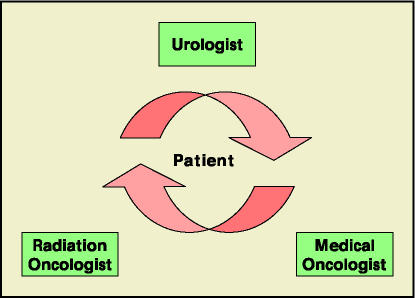

Owing to the diversity of this group, this review attempts to aid the urologist who treats the spectrum of these patients from advanced, symptomatic metastatic disease to the asymptomatic patient on hormonal therapy with a newly discovered increasing PSA. This review outlines a progression of treatment choices that include specific hormonal manipulations, chemotherapeutic options, and adjunctive therapies (Table 1). The clinician must individualize care, as prior therapies, current rate of disease progression, symptoms, and evidence of clinical/radiographic metastatic disease are just a few of the issues that must be considered. Importantly, these patients should have the benefit of multimodality therapy (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Treatment Options for Hormone-Refractory Prostate Cancer

|

Figure 1.

The current multidisciplinary treatment algorithm for patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer.

Hormonal Manipulations

Today, a significant number of patients demonstrate progression while on androgen deprivation therapy with only a PSA increase. Although the optimal timing of therapy has not been established, after ensuring a castrate state in these patients, some type of hormonal therapy represents a reasonable course. Historically it has been recommended to continue androgen deprivation despite disease progression based on the evidence that administration of exogenous testosterone has been shown to worsen patient symptoms.5 It is important at the first evidence of treatment failure that serum testosterone levels be checked to confirm castrate levels (< 50 ng/dL).

Initially, if maximum androgen blockade has not been used, adding an antiandrogen may be helpful. Although several randomized controlled trials have shown that maximum androgen blockade (leuteinizing hormone releasing hormone [LHRH] agonist combined with an antiandrogen) offers a modest survival advantage over LHRH agonist therapy alone, many physicians and patients choose LHRH therapy alone because of cost, side effects, and minimal survival benefit from maximum androgen blockade.6–10

For those patients treated with maximum androgen blockade with an antiandrogen and LHRH agonist, the first therapeutic maneuver can be antiandrogen withdrawal. PSA declines are well recognized, and occasional clinically significant responses such as radiographic changes can be seen.11 The response time of PSA decline will actually depend on the type of antiandrogen used. For example, flutamide has a relatively short half-life of 6 hours, and the response is usually seen within a month. Bicalutamide has a much longer half-life of almost a week, and PSA changes may not be seen for a couple months. Importantly, however, no survival advantage has been identified with this maneuver, and the length of response is usually months.

Potential therapeutic choices would next include initiating second-line hormonal therapies such as less commonly used antiandrogens (eg, nilutamide), adrenal and testicular enzyme inhibitors (eg, ketoconazole), corticosteroids, and estrogens. Patients may respond differently to various antiandrogens, and no comparative trials are available to suggest that one might be better than another. Responses, albeit usually short-lived and biochemical, are possible only for patients who have failed one antiandrogen and are then treated with another one.12,13

Estrogens can be active in patients with both symptomatic and asymptomatic hormone-refractory disease. Lower doses of estrogens (eg, oral diethylstilbestrol [DES] at 1–3 mg) are typically well tolerated except for breast tenderness and gynecomastia. DES at oral doses of 3 mg/d is associated with PSA declines in approximately 42% of patients.14 Adrenal suppressants such as ketoconazole (600–1200 mg/d) plus hydrocortisone have demonstrated PSA reduction and potential reduction of symptoms in single-institution phase II trials.15 Even a smaller dose (300 mg/d) combined with hydrocortisone replacement may have an impact with fewer of the possible toxicities including gastrointestinal distress, visual disturbances, fatigue, and liver function abnormalities.16

Palliation of symptoms and PSA declines have been described in approximately one third of cases treated with low-dose (10–20 mg/d) prednisone.17 Higher PSA response rates have been described with dexamethasone, a more potent glucocorticoid.18 Side effects are well known, and abrupt discontinuation can result in Addisonian crisis.

Chemotherapy

Until the past decade, chemotherapy was regarded as futile in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. No survival advantage over supportive and palliative care measures had been demonstrated. Part of this inability was the difficulty in determining a true “response” in patients with prostate cancer. This was compounded by the mutual urologist and oncologist sentiment that chemotherapy for hormone-refractory patients was not beneficial. As a result, improvement in pain became the endpoint for clinical trials. Mitoxantrone interacts with the DNA topoisomerase II and was studied because of its relatively favorable side-effect profile. Randomized trials comparing mitoxantrone plus a glucocorticoid with a glucocorticoid demonstrated an advantage to combination therapy of quality of life measures and pain palliation. 19,20 Neither trial, however, revealed a survival benefit, but because of its symptomatic palliative impact, mitoxantrone became the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved agent. With the subsequently described docetaxel studies, the role of mitoxantrone will likely diminish, and the treatment algorithm for these patients will change.

Two prospective randomized phase III trials, SWOG 9916 and TAX 327, have established a new standard of care for metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer (Table 2). Early trials showed the possible benefit of single-agent paclitaxel, and the potential increased activity of docetaxel; smaller initial studies demonstrated possible therapeutic benefit. These findings led to the above landmark studies that demonstrated a survival benefit for patients receiving docetaxel and led to FDA approval for thrice-weekly administration in combination with prednisone.

Table 2.

Results of Docetaxel Trials for Hormone-Refractory Prostate Cancer: SWOG 9916 and TAX 327

| SWOG 9916 | TAX 327 | |

|---|---|---|

| Medications | Docetaxel/estramustine | Docetaxel q3wk/ |

| Prednisone | ||

| Median OS (vs M/P) | 17.5 mo (15.6 mo) | 18.9 mo (16.5 mo) |

| Hazard ratio (vs M/P) | 0.8 | 0.76 |

| PSA response (vs M/P) | 50% (27%) | 45% (32%) |

| Neutropenic fever | 5% | 3% |

M/P, mitoxantrone and prednisone; OS, overall survival.

In the SWOG 9916 trial, docetaxel combined with estramustine was compared with mitoxantrone/prednisone. Importantly, overall survival was the primary endpoint with secondary measures including progression-free survival, PSA response, and measurable response rates. The study was powered to detect a 33% overall survival advantage for the docetaxel/estramustine arm. Although the majority of these patients had excellent performance statuses, they had elevated PSA values (84 ng/mL and 90 ng/mL), and bone pain was a symptom in the majority of patients.

With an accrual of 770 patients, SWOG 9916 did not achieve its primary endpoint of a 33% improved survival but demonstrated a 23% improvement in median overall survival when every 3-week doses of docetaxel/estramustine were compared with those of mitoxantrone/prednisone (17.5 months vs 15.6 months; P = .02).21 Importantly, the risk of death was decreased by 20% in the patients receiving docetaxel/estramustine (hazard ratio for death, 0.8). Also, the secondary endpoint of median time to progression was more favorable in the docetaxel/estramustine arm (6.3 months vs 3.2 months; P < .001), as was the endpoint of PSA response (P < .001).

Although there were 16.1% of patients with significant neutropenia, the rate of neutropenic fever was only 5% in patients receiving docetaxel/estramustine. Patients in the docetaxel/estramustine groups did have a higher percentage of cardiovascular events (15% vs 7%), nausea and vomiting (20% vs 5%), neurologic events (7% vs 2%), and metabolic disturbances (6% vs 1%). Eight patients died in the docetaxel/estramustine arm associated with treatment, whereas 4 patients in the mitoxantrone/prednisone arm suffered treatment-related deaths. In this study, there was no statistical difference in subjective pain relief or clinically measurable partial response.21

The TAX 327 trial compared 2 schedules of docetaxel and prednisone with mitoxantrone and prednisone. 22 Patients received docetaxel/prednisone weekly, or they received docetaxel/prednisone every 3 weeks, or they received mitoxantrone/prednisone. Estramustine was not used in this trial. The primary endpoint was overall survival, with secondary endpoints including quality of life, PSA changes, and pain evaluation. More than 1000 patients were enrolled with equivalent patient types in each arm. The median PSAs in all 3 of the treatment groups were greater than 100 ng/mL (range, 108 to 123 ng/mL). Ninety percent of patients had evidence of bony metastatic disease.

In TAX 327 a survival difference was also demonstrated when comparing an every-3-week docetaxel/prednisone with mitoxantrone/prednisone (18.9 months vs 16.5 months; P = .009). However, there was no survival advantage with the weekly dosing of docetaxel/prednisone. As with the SWOG 9916, there was a significantly decreased chance of dying in patients that received docetaxel/prednisone every 3 weeks. The hazard ratio for death was 0.76 in this trial. A significant improvement in pain response, a greater than 50% decrease in serum PSA, and improved quality of life scores were also observed in TAX 327 for docetaxel/prednisone administered every 3 weeks.22 Again, weekly docetaxel/prednisone did not differ from mitoxantrone/prednisone in the reduction of pain.

The rate of significant neutropenia did not differ greatly between the every-3-week docetaxel/prednisone compared with mitoxantrone/prednisone. Importantly, in the every-3-week arm, only 3% of patients had febrile neutropenia. There were more patients with fatigue, gastrointestinal disturbances, alopecia, and neuropathy. Of the 5 patients with treatment-related deaths in this study, 3 patients were in the mitoxantrone/prednisone arm.22

Although questions remain regarding the optimal number of treatment cycles as well as duration of therapy, these studies provide the first prospective, randomized data demonstrating a survival benefit for patients with metastatic hormone-refractory disease treated with docetaxel, a chemotherapeutic agent. These 2 studies have independently confirmed this benefit with an acceptable toxicity/side-effect profile. An every-3-week administration of docetaxel/prednisone now represents the current standard of care. Weekly administration of docetaxel/prednisone is not and should not be considered as therapeutically equivalent to the every-3-week administration of docetaxel/prednisone.

Estramustine did not seem to contribute any benefit, and as a result, the FDA has approved docetaxel/prednisone every 3 weeks for patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. In fact, with the side effects of estramustine that are well recognized, including nausea, vomiting, and cardiovascular/clotting events, estramustine may have been a key contributing factor to the side-effect differences reported in SWOG 9916. The continued role of estramustine in the setting of hormone-refractory prostate cancer seems unwarranted and perhaps harmful.

With these recent findings, the interest in cytotoxic approaches to hormone-refractory prostate cancer has significantly increased. The urologist must continue to evaluate and monitor these patients carefully and consider new treatment regimens currently being studied. Other drug combinations and schedules with docetaxel are the subject of this active clinical investigation. These agents are multiple and include calcitriol (ASCENT trial), bevacizumab (CALGB 90401 trial), oblimersen (EORTC 30021), and risedronic acid (NEPRO). None of these secondary agents have proven more effective than any other newer agent, but enrollment in studies like this are essential to improve the potential benefit of the current treatment regimens. The variety of open trials seeking to improve the docetaxel-based therapy provides an opportunity for the clinician not only to offer treatment choices to patients, but also to help in garnering needed information. Other cytotoxic agents being studied include satraplatin, a third generation oral platinum agent, and ixabepilone, an epothilone B analog.

Novel Treatment Options

Despite these exciting recent advances, current chemotherapeutic approaches are not the ultimate panacea for hormone-refractory disease. As continued attempts are made to improve our understanding regarding the mechanism of androgen-independent prostate cancer, new treatments are being studied to improve clinical effectiveness while decreasing toxicity.

One approach uses immunotherapeutic agents. These include granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-transduced tumor cell vaccine (GVAX®; Cell Genesys, Inc, San Francisco, CA), which elicit a dendritic cell response locally, and sipuleucel-T (Provenge®; Dendreon Corporation, Seattle, WA), which uses autologous antigen-presenting cells loaded with a recombinant fusion protein of prostatic acid phosphatase and GM-CSF.23 Although early primary outcomes have not necessarily shown a significant benefit, some trends toward impact on survival have prompted further study. None of these treatments, however, has been approved by the FDA.

There are other therapeutic approaches such as antisense oligonucleotide therapies (G3139, OGX-011), signal transduction inhibitors (SU5416, gefitinib [Iressa®; AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, LP, Wilmington, DE]), imatinib mesylate (Gleevec™; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ), and receptor blockers (atrasentan, anti-C225, anti-PSMA). These various approaches demonstrate the clinically heterogeneous disease that hormone-refractory prostate cancer represents.

Efforts to define the high-risk patients at an earlier stage have been complicated by the variances in tumor biology. Two current studies include RTOG 0521 and TAX 3501. Both of these studies are adjuvant trials that attempt to identify high-risk patients and initiate treatment before they become hormone-refractory. RTOG 0521 randomizes patients after surgery to hormonal therapy/external beam radiation versus hormonal therapy/docetaxel/external beam radiation treatment. With a projected enrollment of over 2000 participants, TAX 3501 compares randomized groups of patients after prostatectomy who have a high risk of recurrence based on the Kattan postoperative nomogram. Patients receive hormonal therapy or hormonal therapy/docetaxel. These approaches attempt to derail prostate cancer’s advance to the hormone-refractory state.

Conclusion

With the recent large, prospective randomized studies involving taxane therapy, no longer is hormone-refractory prostate cancer considered totally resistant to cytotoxic chemotherapy. Despite the survival benefit with chemotherapy, further advances are necessary and predicated on successfully recruiting patients and completing current and future clinical trials. Our understanding of, and ability to treat, hormone-refractory prostate cancer is constantly evolving, and we must continue to consider different agents and approaches. Hopefully the treatment strategies presented here, including hormonal manipulations, chemotherapeutic options, and novel therapies, can serve as a guide for the individualized care that these patients need and deserve.

Main Points.

Management strategies for patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer must be tailored to the clinical situation of individual patients and their wishes.

Despite castrate levels of testosterone, patients with metastatic disease typically manifested disease progression within 12 to 18 months with a median survival of 2 to 3 years.

Chemotherapy trials involving docetaxel (SWOG 9916 and TAX 327) and immunotherapy are under way.

Although significant progress has been made in understanding and treating hormone-refractory prostate cancer, current treatments do not yet provide a cure.

References

- 1.Eisenberger MA, Carducci MA. Campbell’s Urology. 8th ed. Vol. 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. Chemotherapy for Hormone-Resistant Prostate Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oefelein MG, Agarwal PK, Resnick MI. Survival of patients with hormone refractory prostate cancer in the prostate specific antigen era. J Urol. 2004;171:1525–1528. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000118294.88852.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman BJ, Feldman D. The development of androgen-independent prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:34–45. doi: 10.1038/35094009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holzbeierlein J, Lal P, LaTulippe E, et al. Gene expression analysis of human prostate carcinoma during hormonal therapy identifies androgen-responsive genes and mechanisms of therapy resistance. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:217–227. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63112-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fowler JE, Whitmore WF. The response of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate to exogenous testosterone. J Urol. 1981;126:372–375. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)54531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prostate Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, authors. Maximum androgen blockade in advanced prostate cancer: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2000;355:1491–1498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenberger MA, Blumenstein BA, Crawford ED, et al. Bilateral orchiectomy with or without flutamide for metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1036–1042. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith JA, Chang SS, Keane TE, et al. Androgen deprivation: research, results, and reimbursement. Contemp Urol. 2005;31:244–252. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aprikian AG, Fleshner N, Langleben A, Hames J. An oncology perspective on the benefits and cost of combined androgen blockade in advanced prostate cancer. Can J Urol. 2003;10:1986–1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amling CL. Advanced prostate cancer treatment guidelines: a United States perspective. BJU Int. 2004;94:7–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly WK, Scher HI. Prostate specific antigen decline after antiandrogen withdrawal: the flutamide withdrawal syndrome. J Urol. 1993;149:607–609. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sartor O, Eastham JA. Progressive prostate cancer associated with use of megestrol acetate administered for control of hot flashes. South Med J. 1999;92:415–416. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199904000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scher HI, Liebertz C, Kelly WK, et al. Bicalutamide for advanced prostate cancer: the natural versus treated history of disease. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2928–2938. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.8.2928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith DC, Redman BG, Flaherty LE, et al. A phase II trial of oral diethylstilbesterol as a second-line hormonal agent in advanced prostate cancer. Urology. 1998;52:257–260. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Small EJ, Baron AD, Fippin L, Apodaca D. Ketoconazole retains activity in advanced prostate cancer patients with progression despite flutamide withdrawal. J Urol. 1997;157:1204–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkinson S, Chodak G. An evaluation of intermediate- dose ketoconazole in hormone refractory prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2004;45:581–584. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tannock I, Gospodarowicz M, Meakin W, et al. Treatment of metastatic prostatic cancer with low-dose prednisone: evaluation of pain and quality of life as pragmatic indices of response. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:590–597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.5.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishimura K, Nonomura N, Yasunaga Y, et al. Low doses of oral dexamethasone for hormone-refractory prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;89:2570–2576. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001215)89:12<2570::aid-cncr9>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tannock IF, Osoba D, Stockler MR, et al. Chemotherapy with mitoxantrone plus prednisone or prednisone alone for symptomatic hormone-resistant prostate cancer: a Canadian randomized trial with palliative end points. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1756–1764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.6.1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kantoff PW, Halabi S, Conaway M, et al. Hydrocortisone with or without mitoxantrone in men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: results of the cancer and leukemia group B 9182 study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2506–2513. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petrylak DP, Tangen C, Hussain M, et al. SWOG 99–16: Randomized phase III trial of docetaxel (D)/estramustine (E) versus mitoxantrone (M)/prednisone (P) in men with androgen-independent prostate cancer (AIPCA) Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2004;23 Plenary presentation 3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisenberger MA, De Wit R, Berry W, et al. A multicenter phase III comparison of docetaxel (D) + prednisone (P) and mitoxantrone (MTZ) + P in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer (HRPC) Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2004;23 Plenary presentation 4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Small EJ, Schellhammer PF, Higano CS, et al. Placebo-controlled phase III trial of immunologic therapy with sipuleucel-T (APC8015) in patients with metastatic, asymptomatic hormone refractory prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3089–3094. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]