Abstract

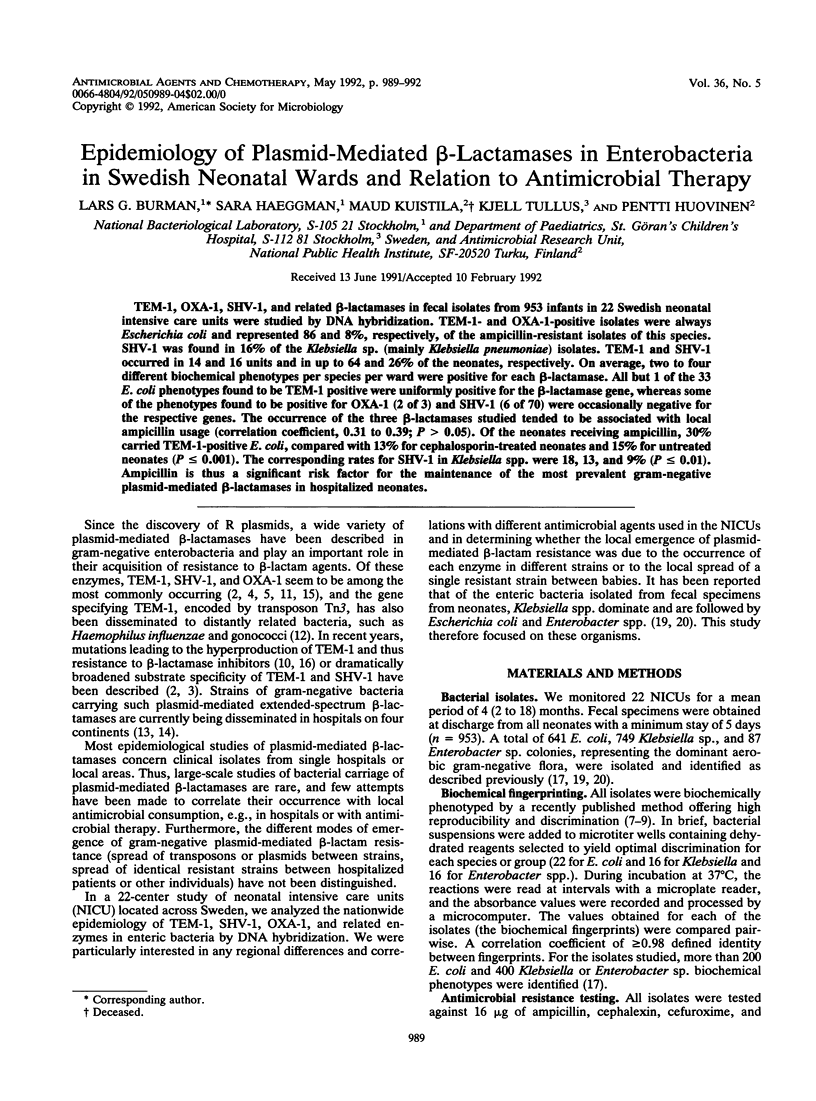

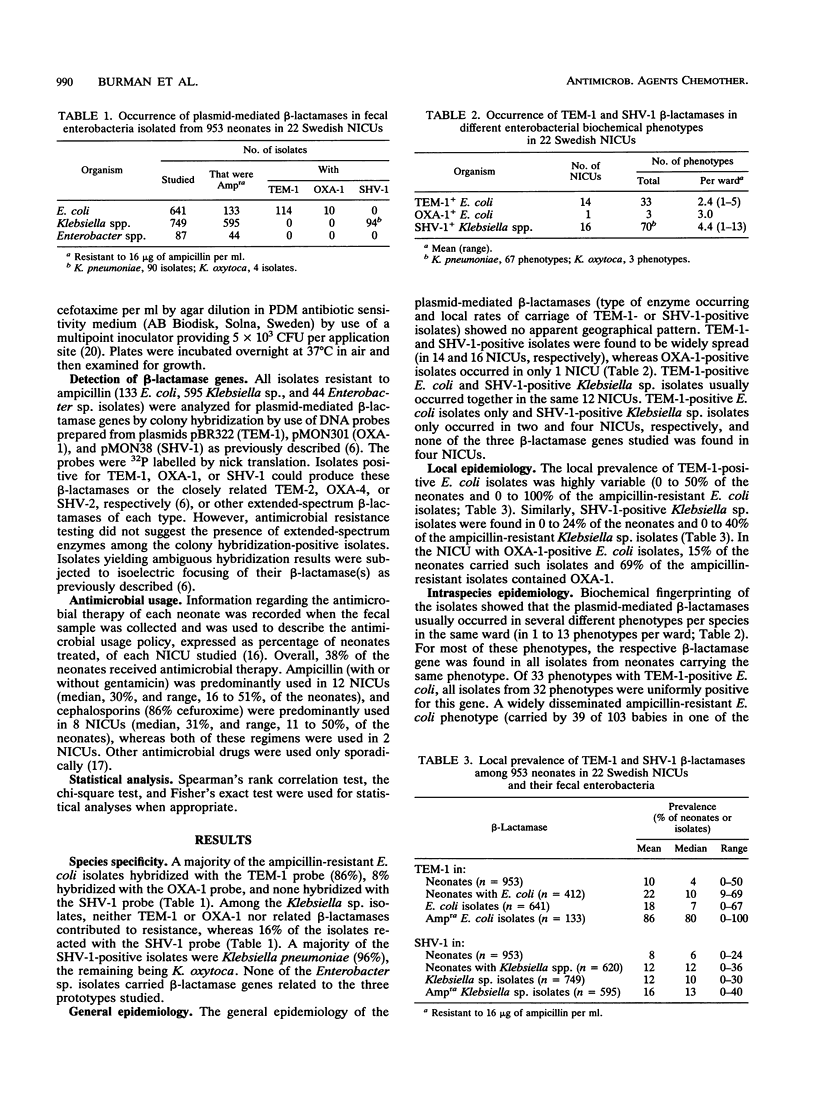

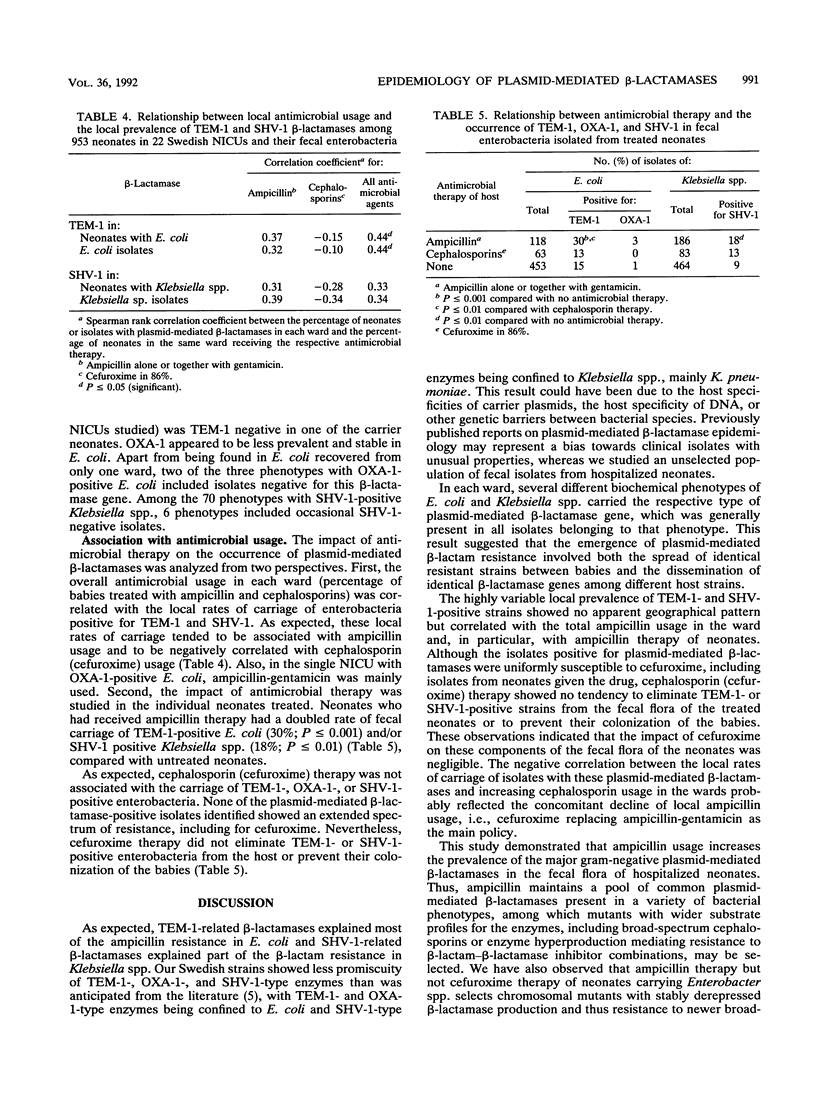

TEM-1, OXA-1, SHV-1, and related beta-lactamases in fecal isolates from 953 infants in 22 Swedish neonatal intensive care units were studied by DNA hybridization. TEM-1- and OXA-1-positive isolates were always Escherichia coli and represented 86 and 8%, respectively, of the ampicillin-resistant isolates of this species. SHV-1 was found in 16% of the Klebsiella sp. (mainly Klebsiella pneumoniae) isolates. TEM-1 and SHV-1 occurred in 14 and 16 units and in up to 64 and 26% of the neonates, respectively. On average, two to four different biochemical phenotypes per species per ward were positive for each beta-lactamase. All but 1 of the 33 E. coli phenotypes found to be TEM-1 positive were uniformly positive for the beta-lactamase gene, whereas some of the phenotypes found to be positive for OXA-1 (2 of 3) and SHV-1 (6 of 70) were occasionally negative for the respective genes. The occurrence of the three beta-lactamases studied tended to be associated with local ampicillin usage (correlation coefficient, 0.31 to 0.39; P greater than 0.05). Of the neonates receiving ampicillin, 30% carried TEM-1-positive E. coli, compared with 13% for cephalosporin-treated neonates and 15% for untreated neonates (P less than or equal to 0.001). The corresponding rates for SHV-1 in Klebsiella spp. were 18, 13, and 9% (P less than or equal to 0.01). Ampicillin is thus a significant risk factor for the maintenance of the most prevalent gram-negative plasmid-mediated beta-lactamases in hospitalized neonates.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bush K. Excitement in the beta-lactamase arena. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989 Dec;24(6):831–836. doi: 10.1093/jac/24.6.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collatz E., Labia R., Gutmann L. Molecular evolution of ubiquitous beta-lactamases towards extended-spectrum enzymes active against newer beta-lactam antibiotics. Mol Microbiol. 1990 Oct;4(10):1615–1620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooksey R., Swenson J., Clark N., Gay E., Thornsberry C. Patterns and mechanisms of beta-lactam resistance among isolates of Escherichia coli from hospitals in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990 May;34(5):739–745. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.5.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster T. J. Plasmid-determined resistance to antimicrobial drugs and toxic metal ions in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1983 Sep;47(3):361–409. doi: 10.1128/mr.47.3.361-409.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huovinen S., Huovinén P., Jacoby G. A. Detection of plasmid-mediated beta-lactamases with DNA probes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988 Feb;32(2):175–179. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J. L., Baquero F. Epidemiology of antibiotic-inactivating enzymes and DNA probes: the problem of quantity. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990 Sep;26(3):301–303. doi: 10.1093/jac/26.3.301-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthew M. Plasmid-mediated beta-lactamases of Gram-negative bacteria: properties and distribution. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1979 Jul;5(4):349–358. doi: 10.1093/jac/5.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu H. C. Overview of mechanisms of bacterial resistance. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989 Jul-Aug;12(4 Suppl):109S–116S. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(89)90122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippon A., Labia R., Jacoby G. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989 Aug;33(8):1131–1136. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.8.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy C., Segura C., Tirado M., Reig R., Hermida M., Teruel D., Foz A. Frequency of plasmid-determined beta-lactamases in 680 consecutively isolated strains of Enterobacteriaceae. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1985 Apr;4(2):146–147. doi: 10.1007/BF02013586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders C. C., Iaconis J. P., Bodey G. P., Samonis G. Resistance to ticarcillin-potassium clavulanate among clinical isolates of the family Enterobacteriaceae: role of PSE-1 beta-lactamase and high levels of TEM-1 and SHV-1 and problems with false susceptibility in disk diffusion tests. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988 Sep;32(9):1365–1369. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.9.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullus K., Berglund B., Fryklund B., Kühn I., Burman L. G. Epidemiology of fecal strains of the family Enterobacteriaceae in 22 neonatal wards and influence of antibiotic policy. J Clin Microbiol. 1988 Jun;26(6):1166–1170. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.6.1166-1170.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullus K., Berglund B., Fryklund B., Kühn I., Burman L. G. Influence of antibiotic therapy on faecal carriage of P-fimbriated Escherichia coli and other gram-negative bacteria in neonates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988 Oct;22(4):563–568. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullus K., Burman L. G. Ecological impact of ampicillin and cefuroxime in neonatal units. Lancet. 1989 Jun 24;1(8652):1405–1407. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullus K., Fryklund B., Berglund B., Källenius G., Burman L. G. Influence of age on faecal carriage of P-fimbriated Escherichia coli and other gram-negative bacteria in hospitalized neonates. J Hosp Infect. 1988 May;11(4):349–356. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(88)90088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]