Abstract

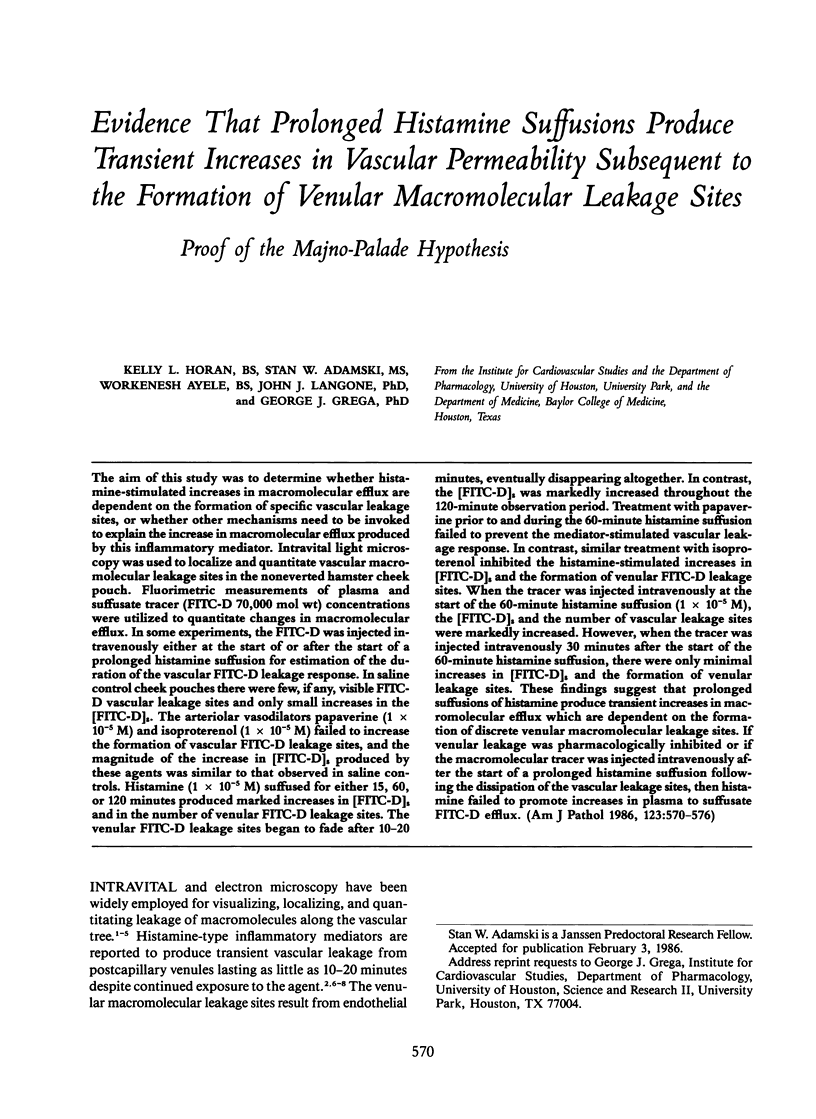

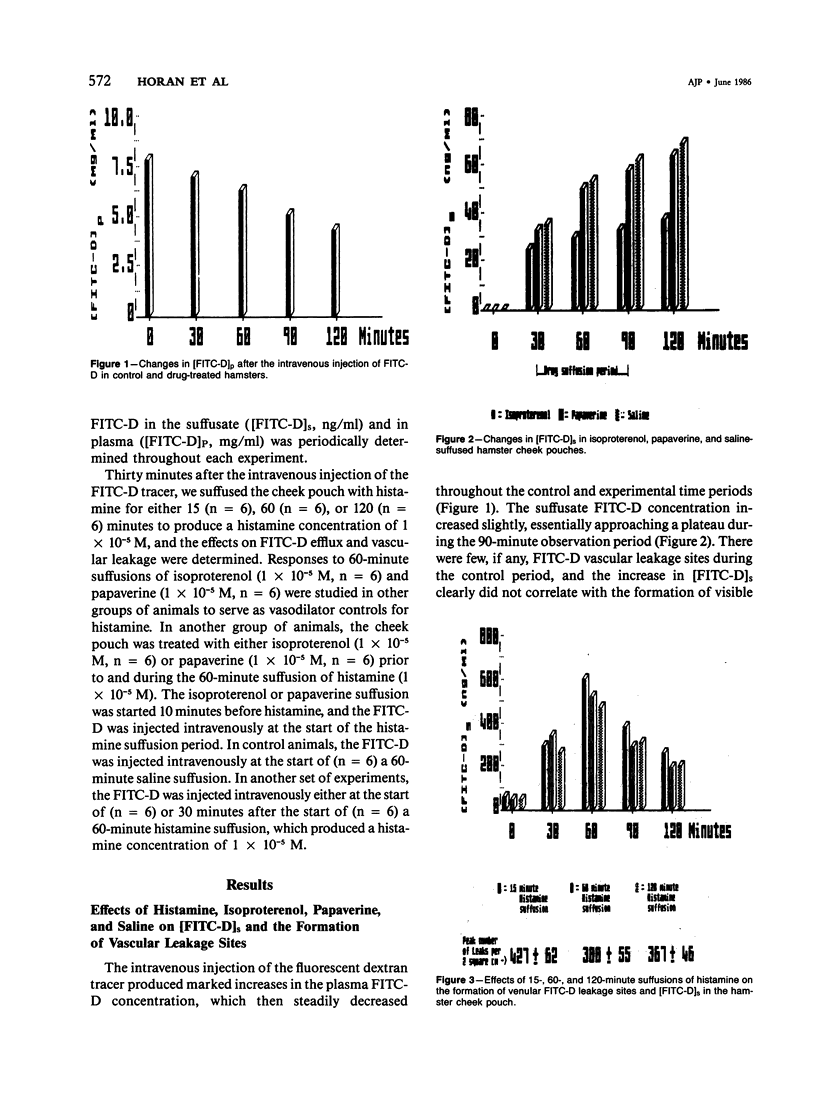

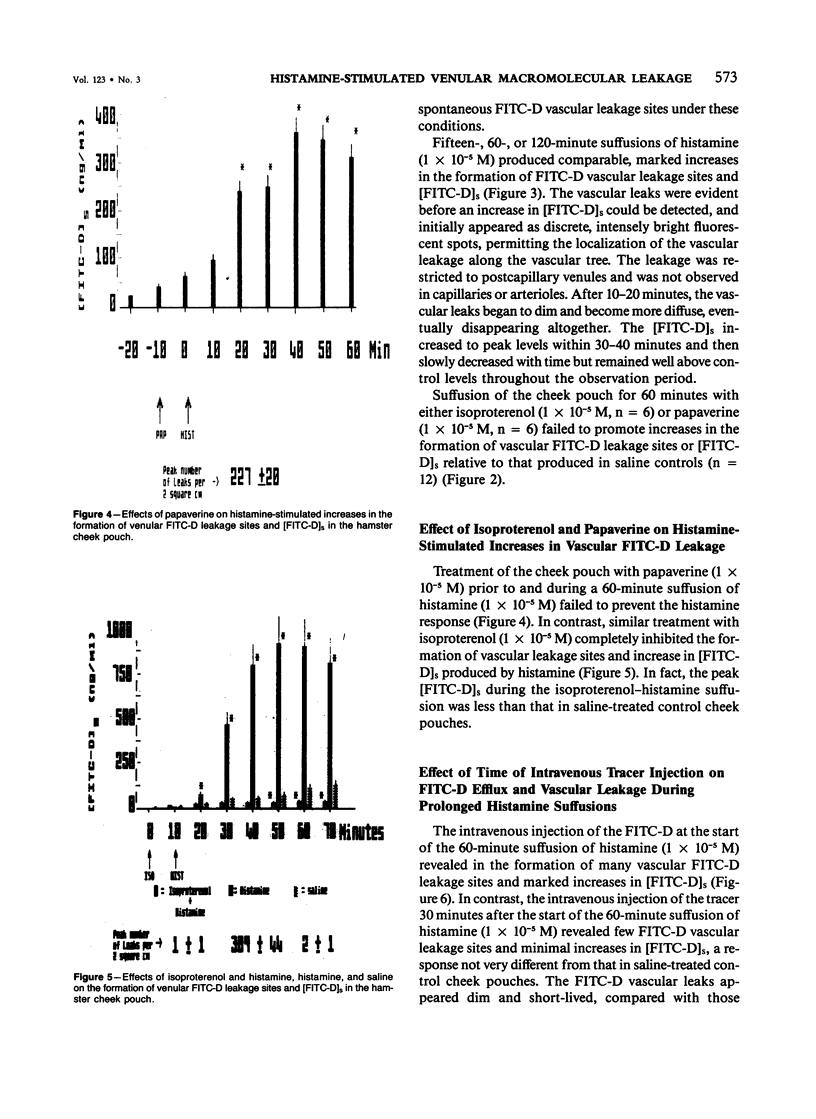

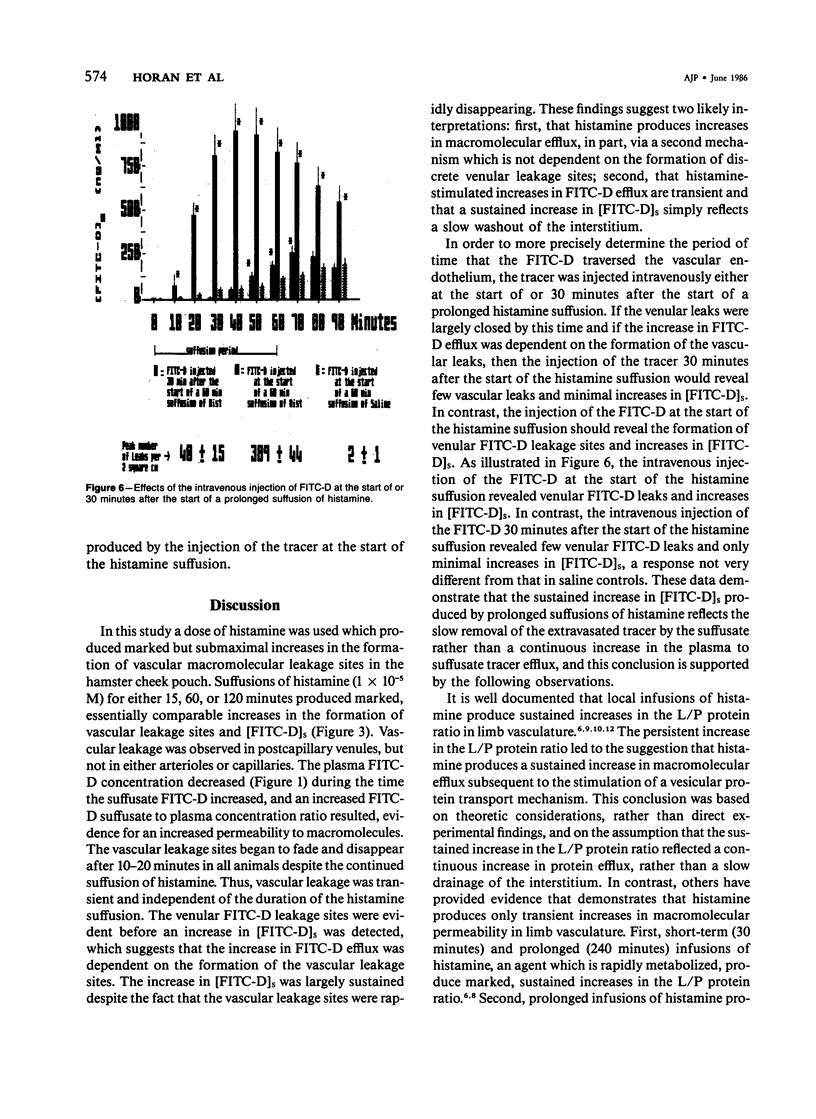

The aim of this study was to determine whether histamine-stimulated increases in macromolecular efflux are dependent on the formation of specific vascular leakage sites, or whether other mechanisms need to be invoked to explain the increase in macromolecular efflux produced by this inflammatory mediator. Intravital light microscopy was used to localize and quantitate vascular macromolecular leakage sites in the noneverted hamster cheek pouch. Fluorimetric measurements of plasma and suffusate tracer (FITC-D 70,000 mol wt) concentrations were utilized to quantitate changes in macromolecular efflux. In some experiments, the FITC-D was injected intravenously either at the start of or after the start of a prolonged histamine suffusion for estimation of the duration of the vascular FITC-D leakage response. In saline control cheek pouches there were few, if any, visible FITC-D vascular leakage sites and only small increases in the [FITC-D]s. The arteriolar vasodilators papaverine (1 X 10(-5) M) and isoproterenol (1 X 10(-5) M) failed to increase the formation of vascular FITC-D leakage sites, and the magnitude of the increase in [FITC-D]s produced by these agents was similar to that observed in saline controls. Histamine (1 X 10(-5) M) suffused for either 15, 60, or 120 minutes produced marked increases in [FITC-D]s and in the number of venular FITC-D leakage sites. The venular FITC-D leakage sites began to fade after 10-20 minutes, eventually disappearing altogether. In contrast, the [FITC-D]s was markedly increased throughout the 120-minute observation period. Treatment with papaverine prior to and during the 60-minute histamine suffusion failed to prevent the mediator-stimulated vascular leakage response. In contrast, similar treatment with isoproterenol inhibited the histamine-stimulated increases in [FITC-D]s and the formation of venular FITC-D leakage sites. When the tracer was injected intravenously at the start of the 60-minute histamine suffusion (1 X 10(-5) M), the [FITC-D]s and the number of vascular leakage sites were markedly increased. However, when the tracer was injected intravenously 30 minutes after the start of the 60-minute histamine suffusion, there were only minimal increases in [FITC-D]s and the formation of venular leakage sites. These findings suggest that prolonged suffusions of histamine produce transient increases in macromolecular efflux which are dependent on the formation of discrete venular macromolecular leakage sites.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Becker C. G., Nachman R. L. Contractile proteins of endothelial cells, platelets and smooth muscle. Am J Pathol. 1973 Apr;71(1):1–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonassisi V., Venter J. C. Hormone and neurotransmitter receptors in an established vascular endothelial cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976 May;73(5):1612–1616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.5.1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone C. Modulation of solute permeability in microvascular endothelium. Fed Proc. 1986 Feb;45(2):77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clerck F., De Brabander M., Neels H., Van de Velde V. Direct evidence for the contractile capacity of endothelial cells. Thromb Res. 1981 Sep 15;23(6):505–520. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(81)90174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham B. M., Hechtman H. B., Valeri C. R., Shepro D. Antiinflammatory agents inhibit microvascular permeability induced by leukotrienes and by stimulated human neutrophils. Microcirc Endothelium Lymphatics. 1984 Aug;1(4):465–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J., Galey F., Wayland H. Action of histamine on the mesenteric microvasculature. Microvasc Res. 1980 Jan;19(1):108–126. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(80)90087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furchgott R. F. Role of endothelium in responses of vascular smooth muscle. Circ Res. 1983 Nov;53(5):557–573. doi: 10.1161/01.res.53.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grega G. J., Maciejko J. J., Raymond R. M., Sak D. P. The interrelationship among histamine, various vasoactive substances, and macromolecular permeability in the canine forelimb. Circ Res. 1980 Feb;46(2):264–275. doi: 10.1161/01.res.46.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammerschmidt D. E., Harris P. D., Wayland J. H., Craddock P. R., Jacob H. S. Complement-induced granulocyte aggregation in vivo. Am J Pathol. 1981 Feb;102(2):146–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heltianu C., Simionescu M., Simionescu N. Histamine receptors of the microvascular endothelium revealed in situ with a histamine-ferritin conjugate: characteristic high-affinity binding sites in venules. J Cell Biol. 1982 May;93(2):357–364. doi: 10.1083/jcb.93.2.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joris I., Majno G., Ryan G. B. Endothelial contraction in vivo: a study of the rat mesentery. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol. 1972;12(1):73–83. doi: 10.1007/BF02893987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner W. L., Carter R. D., Raizes G. S., Renkin E. M. Influence of histamine and some other substances on blood-lymph transport of plasma protein and dextran in the dog paw. Microvasc Res. 1974 Jan;7(1):19–30. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(74)90034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner W. L., Svensjö E., Arfors K. E. Simultaneous measurements of macromolecular leakage and arteriolar blood flow as altered by PGE1 and beta 2-receptor stimulant in the hamster cheek pouch. Microvasc Res. 1979 Nov;18(3):301–310. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(79)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthuis R. J., Wang C. Y., Scott J. B. Transient effects of histamine on microvascular fluid movement. Microvasc Res. 1982 May;23(3):316–328. doi: 10.1016/s0026-2862(82)80004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthuis R. J., Wang C. Y., Spielman W. S. Transient effects of histamine on the capillary filtration coefficient. Microvasc Res. 1984 Nov;28(3):322–344. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(84)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laposata M., Dovnarsky D. K., Shin H. S. Thrombin-induced gap formation in confluent endothelial cell monolayers in vitro. Blood. 1983 Sep;62(3):549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAJNO G., PALADE G. E. Studies on inflammation. 1. The effect of histamine and serotonin on vascular permeability: an electron microscopic study. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1961 Dec;11:571–605. doi: 10.1083/jcb.11.3.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majno G., Shea S. M., Leventhal M. Endothelial contraction induced by histamine-type mediators: an electron microscopic study. J Cell Biol. 1969 Sep;42(3):647–672. doi: 10.1083/jcb.42.3.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhan W. G., Joyner W. L. The effect of altering the external calcium concentration and a calcium channel blocker, verapamil, on microvascular leaky sites and dextran clearance in the hamster cheek pouch. Microvasc Res. 1984 Sep;28(2):159–179. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(84)90015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller F. N., Joshua I. G., Anderson G. L. Quantitation of vasodilator-induced macromolecular leakage by in vivo fluorescent microscopy. Microvasc Res. 1982 Jul;24(1):56–67. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(82)90042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata H., Guth P. H. Effect of topical histamine on mucosal microvascular permeability and acid secretion in the rat stomach. Am J Physiol. 1984 Jun;246(6 Pt 1):G654–G659. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1984.246.6.G654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen S. P. A calcium-dependent reversible permeability increase in microvessels in frog brain, induced by serotonin. J Physiol. 1985 Apr;361:103–113. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renkin E. M., Carter R. D., Joyner W. L. Mechanism of the sustained action of histamine and bradykinin on transport of large molecules across capillary walls in the dog paw. Microvasc Res. 1974 Jan;7(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(74)90036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shasby D. M., Shasby S. S., Sullivan J. M., Peach M. J. Role of endothelial cell cytoskeleton in control of endothelial permeability. Circ Res. 1982 Nov;51(5):657–661. doi: 10.1161/01.res.51.5.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensjö E., Arfors K. E., Raymond R. M., Grega G. J. Morphological and physiological correlation of bradykinin-induced macromolecular efflux. Am J Physiol. 1979 Apr;236(4):H600–H606. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.4.H600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensjö E., Persson C. G., Rutili G. Inhibition of bradykinin induced macromolecular leakage from post-capillary venules by a beta2-adrenoreceptor stimulant, terbutaline. Acta Physiol Scand. 1977 Dec;101(4):504–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1977.tb06038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson P. D. Effect of plasma and red blood cells on water permeability in cat hindlimb. Am J Physiol. 1984 Jun;246(6 Pt 2):H818–H823. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.6.H818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]