Abstract

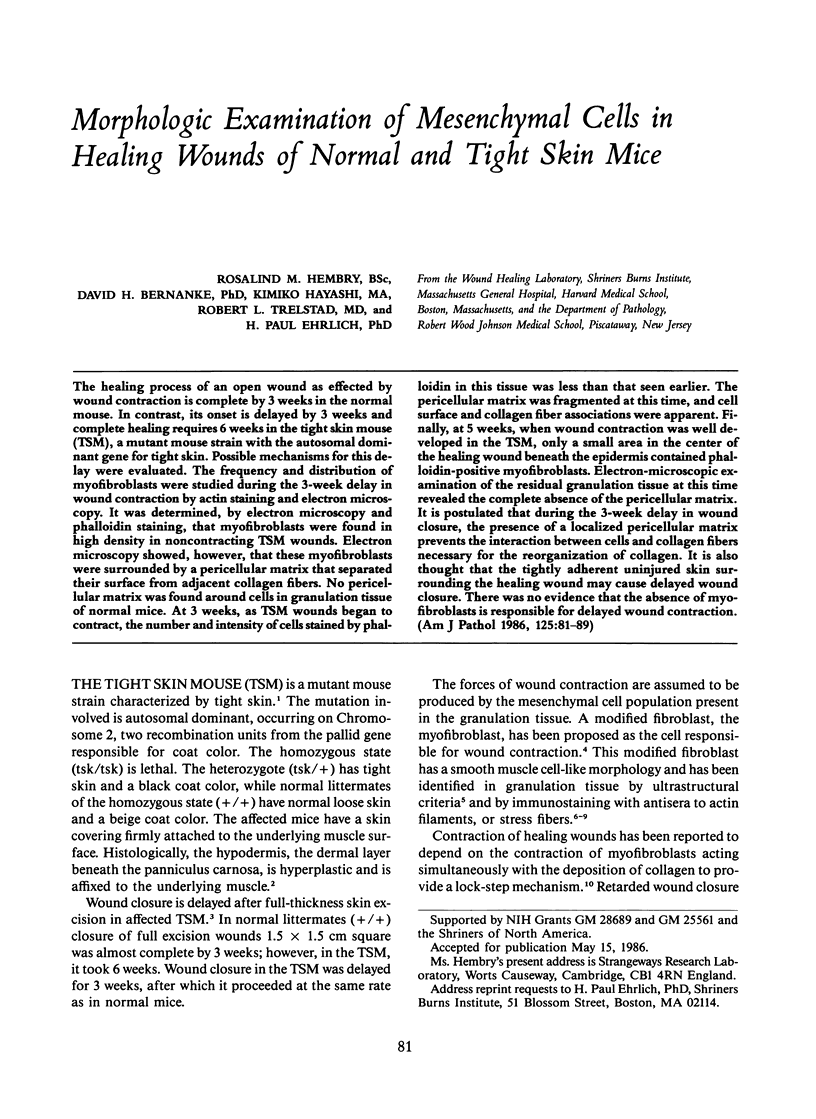

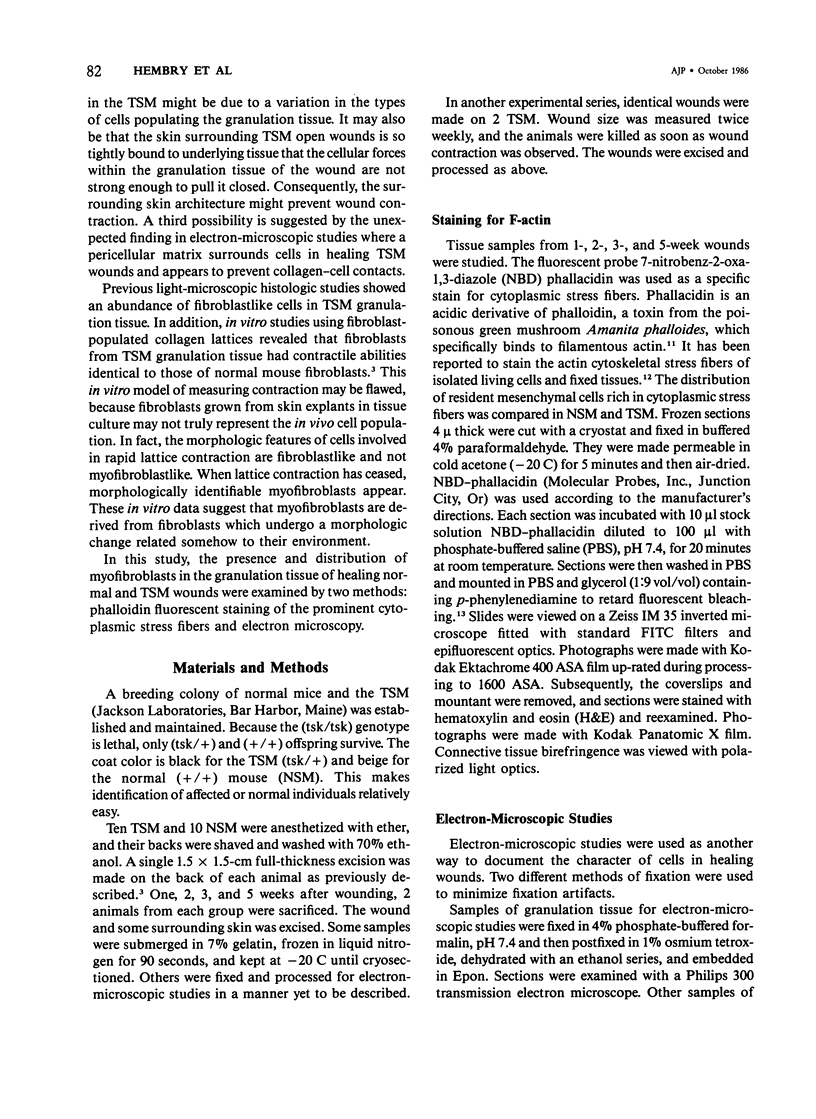

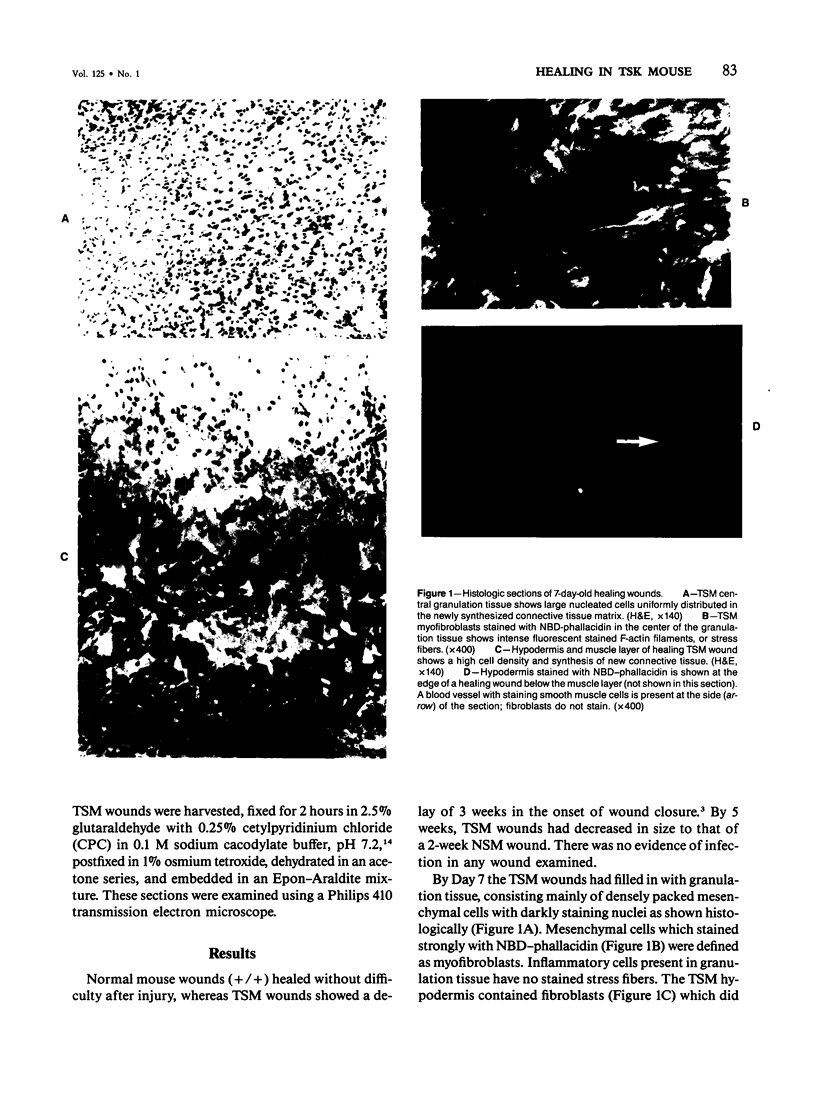

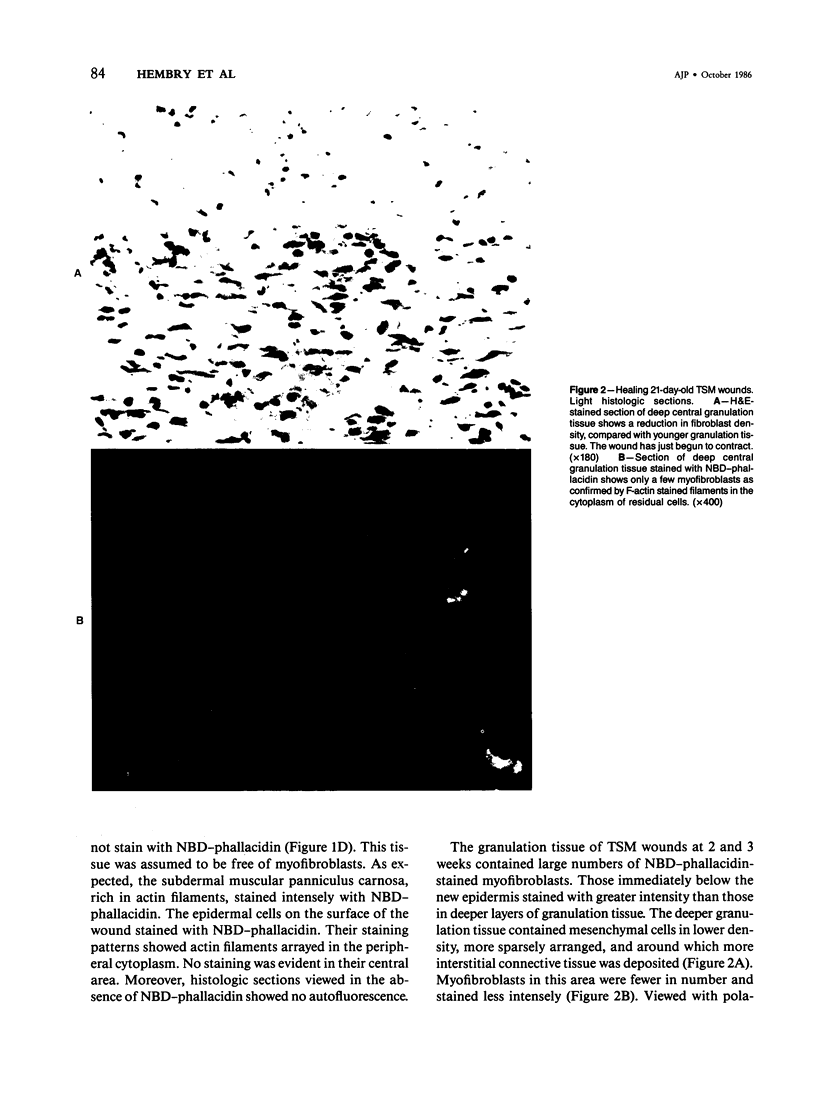

The healing process of an open wound as effected by wound contraction is complete by 3 weeks in the normal mouse. In contrast, its onset is delayed by 3 weeks and complete healing requires 6 weeks in the tight skin mouse (TSM), a mutant mouse strain with the autosomal dominant gene for tight skin. Possible mechanisms for this delay were evaluated. The frequency and distribution of myofibroblasts were studied during the 3-week delay in wound contraction by actin staining and electron microscopy. It was determined, by electron microscopy and phalloidin staining, that myofibroblasts were found in high density in noncontracting TSM wounds. Electron microscopy showed, however, that these myofibroblasts were surrounded by a pericellular matrix that separated their surface from adjacent collagen fibers. No pericellular matrix was found around cells in granulation tissue of normal mice. At 3 weeks, as TSM wounds began to contract, the number and intensity of cells stained by phalloidin in this tissue was less than that seen earlier. The pericellular matrix was fragmented at this time, and cell surface and collagen fiber associations were apparent. Finally, at 5 weeks, when wound contraction was well developed in the TSM, only a small area in the center of the healing wound beneath the epidermis contained phalloidin-positive myofibroblasts. Electron-microscopic examination of the residual granulation tissue at this time revealed the complete absence of the pericellular matrix. It is postulated that during the 3-week delay in wound closure, the presence of a localized pericellular matrix prevents the interaction between cells and collagen fibers necessary for the reorganization of collagen. It is also thought that the tightly adherent uninjured skin surrounding the healing wound may cause delayed wound closure. There was no evidence that the absence of myofibroblasts is responsible for delayed wound contraction.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ABERCROMBIE M., JAMES D. W., NEWCOMBE J. F. Wound contraction in rabbit skin, studied by splinting the wound margins. J Anat. 1960 Apr;94:170–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen R. D., Francis D. W., Nakajima H. Cyclic birefringence changes in pseudopods of Chaos carolinensis revealing the localization of the motive force in pseudopod extension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1965 Oct;54(4):1153–1161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.4.1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barak L. S., Yocum R. R., Nothnagel E. A., Webb W. W. Fluorescence staining of the actin cytoskeleton in living cells with 7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole-phallacidin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Feb;77(2):980–984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.2.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E., Ivarsson B., Merrill C. Production of a tissue-like structure by contraction of collagen lattices by human fibroblasts of different proliferative potential in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Mar;76(3):1274–1278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolami C., Donoff R. B. The effect of full-thickness skin grafts on the actomyosin content of contracting wounds. J Oral Surg. 1979 Jul;37(7):471–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich H. P., Needle A. L. Wound healing in tight-skin mice: delayed closure of excised wounds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983 Aug;72(2):190–198. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198308000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbiani G., Hirschel B. J., Ryan G. B., Statkov P. R., Majno G. Granulation tissue as a contractile organ. A study of structure and function. J Exp Med. 1972 Apr 1;135(4):719–734. doi: 10.1084/jem.135.4.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbiani G., Ryan G. B., Majne G. Presence of modified fibroblasts in granulation tissue and their possible role in wound contraction. Experientia. 1971 May 15;27(5):549–550. doi: 10.1007/BF02147594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M. C., Sweet H. O., Bunker L. E. Tight-skin, a new mutation of the mouse causing excessive growth of connective tissue and skeleton. Am J Pathol. 1976 Mar;82(3):493–512. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A. K., Wild P., Stopak D. Silicone rubber substrata: a new wrinkle in the study of cell locomotion. Science. 1980 Apr 11;208(4440):177–179. doi: 10.1126/science.6987736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaysman J. E., Pegrum S. M. Early contacts between fibroblasts. An ultrastructural study. Exp Cell Res. 1973 Mar 30;78(1):71–78. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(73)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschel B. J., Gabbiani G., Ryan G. B., Majno G. Fibroblasts of granulation tissue: immunofluorescent staining with antismooth muscle serum. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1971 Nov;138(2):466–469. doi: 10.3181/00379727-138-35920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez S. A., Millan A., Bashey R. I. Scleroderma-like alterations in collagen metabolism occurring in the TSK (tight skin) mouse. Arthritis Rheum. 1984 Feb;27(2):180–185. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson G. D., Nogueira Araujo G. M. A simple method of reducing the fading of immunofluorescence during microscopy. J Immunol Methods. 1981;43(3):349–350. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(81)90183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markwald R. R., Fitzharris T. P., Bernanke D. H. Morphologic recognition of complex carbohydrates in embryonic cardiac extracellular matrix. J Histochem Cytochem. 1979 Aug;27(8):1171–1173. doi: 10.1177/27.8.479561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath M. H., Hundahl S. A. The spatial and temporal quantification of myofibroblasts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982 Jun;69(6):975–985. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198206000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menton D. N., Hess R. A., Lichtenstein J. R., Eisen A. The structure and tensile properties of the skin of tight-skin (Tsk) mutant mice. J Invest Dermatol. 1978 Jan;70(1):4–10. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12543353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menton D. N., Hess R. A. The ultrastructure of collagen in the dermis of tight-skin (Tsk) mutant mice. J Invest Dermatol. 1980 Mar;74(3):139–147. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12535041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen J. S., Toh B. H., Mackay I. R., Tait B. D., Gust I. D., Kastelan A., Hadzic N. Segregation of autoantibody to cytoskeletal filaments, actin and intermediate filaments with two types of chronic active hepatitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1982 Jun;48(3):527–532. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg G. T., Ross S. C., Osborn T. G. Glycosaminoglycan content in the lung of the tight-skin mouse. J Rheumatol. 1984 Jun;11(3):318–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S. C., Osborn T. G., Dorner R. W., Zuckner J. Glycosaminoglycan content in skin of the tight-skin mouse. Arthritis Rheum. 1983 May;26(5):653–657. doi: 10.1002/art.1780260512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph R. Location of the force of wound contraction. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1979 Apr;148(4):547–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rungger-Brändle E., Gabbiani G. The role of cytoskeletal and cytocontractile elements in pathologic processes. Am J Pathol. 1983 Mar;110(3):361–392. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. L., Condeelis J. S., Moore P. L., Allen R. D. The contractile basis of amoeboid movement. I. The chemical control of motility in isolated cytoplasm. J Cell Biol. 1973 Nov;59(2 Pt 1):378–394. doi: 10.1083/jcb.59.2.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toh B. H. Smooth muscle autoantibodies and autoantigens. Clin Exp Immunol. 1979 Dec;38(3):621–628. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasek J. J., Hay E. D., Fujiwara K. Collagen modulates cell shape and cytoskeleton of embryonic corneal and fibroma fibroblasts: distribution of actin, alpha-actinin, and myosin. Dev Biol. 1982 Jul;92(1):107–122. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland T., Faulstich H. Amatoxins, phallotoxins, phallolysin, and antamanide: the biologically active components of poisonous Amanita mushrooms. CRC Crit Rev Biochem. 1978 Dec;5(3):185–260. doi: 10.3109/10409237809149870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]