SYNOPSIS

Objectives.

Effective response to large-scale public health threats requires well-coordinated efforts among individuals and agencies. While guidance is available to help states put emergency planning programs into place, little has been done to evaluate the human infrastructure that facilitates successful implementation of these programs. This study examined the human infrastructure of the Missouri public health emergency planning system in 2006.

Methods.

The Center for Emergency Response and Terrorism (CERT) at the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services has responsibility for planning, guiding, and funding statewide emergency response activities. Thirty-two public health emergency planners working primarily in county health departments contract with CERT to support statewide preparedness. We surveyed the planners to determine whom they communicate with, work with, seek expertise from, and exchange guidance with regarding emergency preparedness in Missouri.

Results.

Most planners communicated regularly with planners in their region but seldom with planners outside their region. Planners also reported working with an average of 12 local entities (e.g., emergency management, hospitals/clinics). Planners identified the following leaders in Missouri's public health emergency preparedness system: local public health emergency planners, state epidemiologists, the state vaccine and grant coordinator, regional public health emergency planners, State Emergency Management Agency area coordinators, the state Strategic National Stockpile coordinator, and Federal Bureau of Investigation Weapons of Mass Destruction coordinators. Generally, planners listed few federal-level or private-sector individuals in their emergency preparedness networks.

Conclusions.

While Missouri public health emergency planners maintain large and varied emergency preparedness networks, there are opportunities for strengthening existing ties and seeking additional connections.

We salute the exceptions to the rule, or, more accurately, the exceptions that proved the rule. People like Mike Ford, the owner of three nursing homes who wisely chose to evacuate his patients in Plaquemines Parish before Katrina hit, due in large part to his close and long-standing working relationship with Jesse St. Amant, Director of the Plaquemines Office of Emergency Preparedness. (A Failure of Initiative, House Report on the Katrina Response, 2006)

Research and experience have shown that effective response to large-scale public health threats, such as disease outbreaks, natural disasters, and terrorist attacks, requires well-coordinated efforts among individuals and agencies.1–3 Maintaining effective levels of coordination can be difficult as public health systems typically consist of individuals and agencies working at multiple levels and representing a wide variety of stakeholders.2,4,5 As a result, public health researchers and practitioners have begun to adopt a systems approach to the development, understanding, and evaluation of public health programs.3,4 This approach takes into consideration not only characteristics of specific individuals or agencies, but also the relationships among them.

In recent years, systems approaches have been slowly gaining momentum in areas within public health.6–8 However, little has been done in emergency preparedness. During recent disasters in New York and New Orleans, it became clear that the field of emergency preparedness could benefit from adopting this approach. Lack of coordination and communication at multiple levels were cited as major reasons why many of the disaster planning and relief efforts failed during Hurricane Katrina9 and why, although generally considered a success story where emergency response is concerned, the 9/11 response could have been even more effective.3,5 In fact, during his testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives in 2005,10 Dr. H. Dan O'Hair, Professor and First Vice President of the National Communication Association, cited the understanding of complex disaster planning and response systems as one of six major areas in need of further study.

Emergency response and preparedness systems span the local, state, and federal levels, but much of the responsibility for planning and activities falls to state health departments.11 While guidance is available from the federal government to help state health departments establish emergency plans and programs, little has been done to help states understand or evaluate the underlying systems of individuals and agencies that facilitate the implementation of these programs. In general, guidance provided to state programs has focused on assisting with the development of written emergency planning documents. While necessary, this focus can take emphasis away from implementing planned activities and achieving emergency preparedness.1 State health departments need practical information about communication and coordination among emergency planning staff and among emergency planning staff and local, state, and federal stakeholders. Such information would allow state health departments to understand and strengthen their existing infrastructure and make informed decisions when faced with changes in funding, political climate, or threats to public safety.

PROJECT DESCRIPTION

The goal of this project was to understand and describe Missouri's public health emergency preparedness system by examining the connections that local public health emergency planners utilize to facilitate emergency planning and response. Because it is uniquely suited to examining connections, we used social network analysis (SNA) for this study. SNA has a focus on relationships of subjects to each other or to others rather than on relationships between various subject attributes. Our study design, data collection, and data analysis incorporated this focus.

For decades, the business community has been using SNA to examine the informal social networks that emerge among members of organizations.12–15 By asking employees questions such as, “Whom do you go to for help or advice at least one day a week?” or “Whom would you trust to keep in confidence your concerns about a work-related issue?” businesses have identified leaders and built teams that take advantage of existing social roles and social structures. The use of existing relationships has proven to be a successful strategy for improving the effectiveness and productivity of organizations. By taking this approach, we aim to improve the effectiveness of public health emergency planning as well.

Using SNA, we examined: (1) communication among public health emergency planners in Missouri, (2) partnerships between public health emergency planners and local entities (e.g., police, schools), (3) communication between public health emergency planners and hospital planners, and (4) who public health emergency planners communicate with, seek expertise from, and exchange guidance with regarding Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) planning and All-Hazards Planning (AHP).

Emergency preparedness in Missouri

The Center for Emergency Response and Terrorism (CERT) at the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services has overall responsibility for planning, guiding, and funding public health emergency response activities for Missouri. In 2006, CERT contracted with 32 local public health agencies (LPHAs) to support preparedness initiatives at the local level for all 114 Missouri counties. These contracts included funding for a maximum of 33 local public health emergency planners, most with responsibility for multiple counties.

Missouri's local public health emergency planners work in conjunction with state and local staff to mitigate conditions that impact public health, with emphasis on bioterrorism, outbreaks of infectious disease, and other public health threats and emergencies.16 Planners are responsible for: (1) developing a functional local public health emergency preparedness and response plan, (2) identifying and implementing protocols for the plan, (3) developing partnerships among regional entities for emergency preparedness and response, and (4) coordinating local surveillance activities to ensure rapid detection of public health concerns.

Examples of tasks that fall under these broad responsibilities include: developing a plan for clinic flow in the event of a mass vaccination, disseminating information to the local community about what to do during a disaster, and coordinating with hospitals supporting the response to public health emergencies. These tasks and responsibilities are based on the objectives described in detail in the People Prepared for Emergent Health Threats section of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Health Protection Goals.17

Two aspects of the planner role are unique to public health emergency planners (as opposed to emergency preparedness professionals outside of public health). First, for emergencies that are specifically public health-related (e.g., pandemic influenza outbreak, bioterrorism event), public health emergency planners become the first responders. Second, for other emergencies (e.g., earthquake, flood), public health emergency planners work closely with other emergency response professionals to specifically address public health aspects of the emergency. For example, during widespread power outages in St. Louis in the summer of 2006, the planners assisted hospitals in contacting the emergency operations center to request backup generators, supplied hospitals with two-way radios, and scheduled registered nurses to work at cooling shelters.

While the educational background and experience required to be a Missouri public health emergency planner varies based on which agency hires the planner, all Missouri local public health emergency planners complete the following training within 10 months of their beginning contract date.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Independent Study (IS) Program:18 IS 700 National Incident Management System (NIMS)

FEMA Independent Study Program: IS 100 Introduction to Incident Command System (ICS)

FEMA Independent Study Program: IS 200 Basic ICS

FEMA Independent Study Program: IS 800 National Response Plan

FEMA Classroom Study Program: ICS 300 Intermediate ICS

In addition, planners are required to participate in an annual state-sponsored SNS statewide exercise or state-sponsored SNS rural exercise. All planners are encouraged to take two epidemiology courses and, while not required, several of the planners have taken federal SNS training.

METHODS

In February and March 2006, the 31 local public health emergency planners contracting with CERT at the time completed a survey regarding their work in emergency planning and response in Missouri. Survey questions included information about planner experience in emergency preparedness, questions regarding the agencies and individuals with whom each planner collaborated, questions about AHP and SNS networks, and space for additional comments. The Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Measures

Each participant was asked about his or her current and past experience in emergency preparedness. We hypothesized that more experienced planners would be more central within the network of planners and act as resources for others more often. The four experience questions determined length of agency employment, length of time in current position, length of time in emergency preparedness, and amount of time spent per week on emergency preparedness.

Multiple-choice questions regarding planner collaboration covered: (1) what entities planners worked with at a local level (e.g., academic institutions, businesses, emergency management), (2) the frequency of communication among local public health planners, (3) the frequency of communication between local and regional public health planners, and (4) communication between local planners and hospital planners. Open-ended questions regarding AHP and SNS networks allowed planners to list up to three people at the local, state, and federal levels that they communicated with, sought expertise from, or with which they exchanged guidance. Planners were also given the opportunity to include additional comments.

SNA was the primary method of analysis for this study; we used Pajek 1.0919 for all network analyses, including descriptive statistics and network visualization. We calculated non-network-related statistics using SPSS Version 13.0.20

RESULTS

Characteristics of the planners and their regions

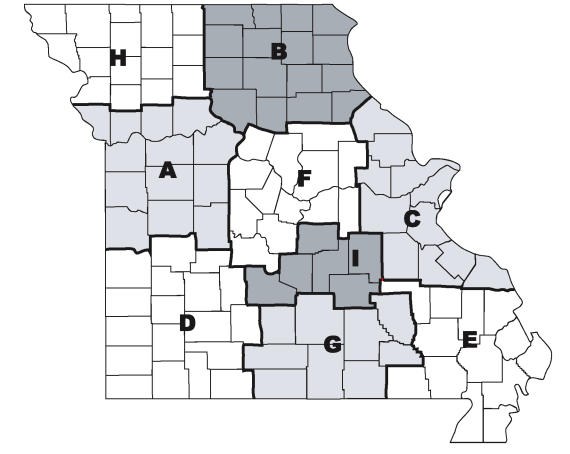

With the goal of facilitating collaboration among the local public health emergency planners and other first responders in Missouri, each planner worked in one of nine regions with borders defined using the state highway patrol regions. The Missouri Highway Patrol regions are well established among groups with which the emergency planners must coordinate. Each region consists of six or more counties and was covered by up to eight planners (Figure 1, Table 1). The number of planners per 100,000 people ranged from 0.4 to 1.3.

Figure 1.

Map of Missouri regions covered by local public health emergency planners

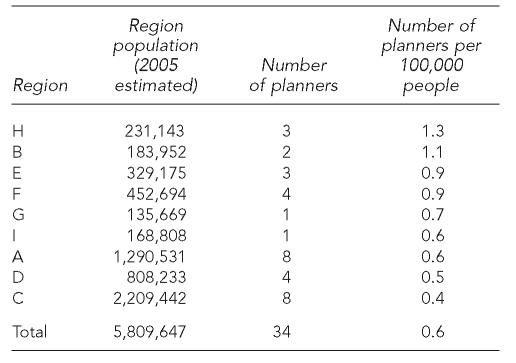

Table 1.

Planner regions ordered by number of planners per 100,000 people

Most planners had some experience with emergency preparedness before their current job, with 42% indicating that they had more than 10 years of prior experience. Most (65%) had held the position of local planner for three to five years. All planners reported spending 50% to 100% of their time on emergency planning-related activities.

Communication among local planners

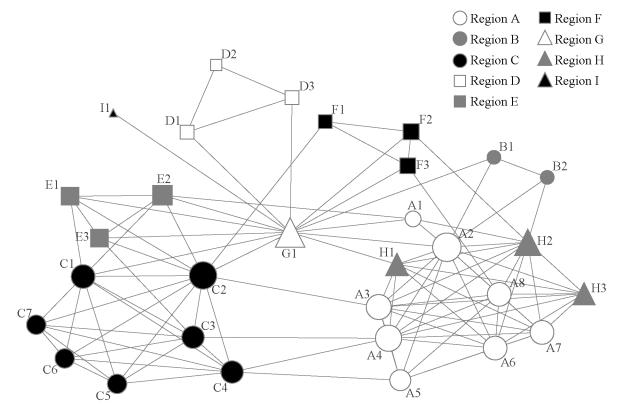

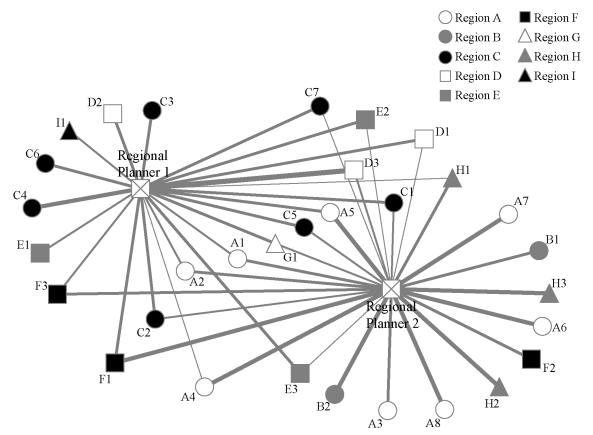

Planners were asked how often they communicated with other local public health planners in Missouri. The response choices were: never, yearly, quarterly, monthly, weekly, or daily. Figure 2 shows the resulting network, which depicts regular communication among local public health planners at the time of the survey. A line between two nodes indicates that the two planners communicated more than quarterly. The density of the network was 0.23. Density is a ratio of existing to possible connections; in this case, it showed that 23% of possible connections between planners existed. The color and shape of a node indicate which region a planner worked in, and the size of a node is based on degree. Degree is a measure of how many connections a node has; in this case, it shows the number of planners each planner was communicating with on a regular basis.

Figure 2.

Regular communication among Missouri local public health emergency planners

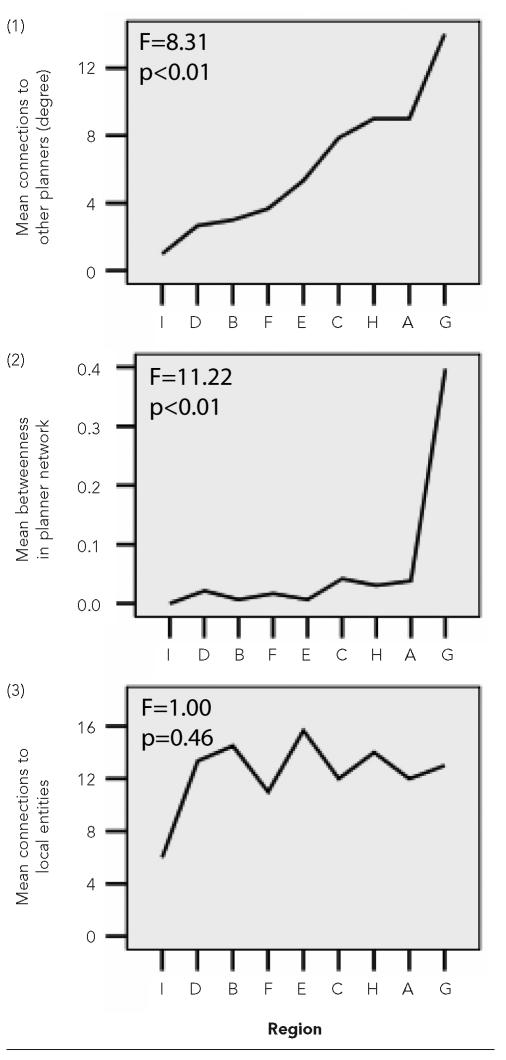

The range of degree in this network was 1–14, with 6 being the median. Degree can be used to determine how central or active each planner is in the network; the higher the degree, the more the planner is communicating with others. Planner G1 had the highest degree and was therefore considered extremely central to communication among the local planners. Planners A2 and C2 also appeared central to the network. Degree varied significantly by region (F=8.31, p<0.01), with the planner in Region I having the lowest degree and the planner in Region G having the highest degree (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Means plots by region for (1) number of connections (degree) in the planner network, (2) betweenness centrality in the planner network, and (3) number of connections to local entities

We also compared the degree of the planners with the total amount of time they reported being in emergency preparedness. While there was no significant difference overall (F=0.85, p=0.54), the three planners with the highest degree (planners G1, C2, and A2) had also been in emergency preparedness for the longest amount of time.

Another measure of centrality is betweenness, which, in this case, indicated how often a planner facilitated a connection between other planners who were otherwise not connected. By acting as a bridge between planners, planners with higher betweenness had more control over the flow of information in the network. For example, planner G1 was connected to planner D1 and planner E2, who were not directly connected to each other. By facilitating the connection between planners D1 and E2, planner G1 had some control over information flow between the two.

When we compared the mean betweenness by region, we found a significant difference (F=11.22. p<0.01) between regions (Figure 3). However, there was no significant difference in the mean betweenness (F=0.90, p=0.51) by length of employment in emergency planning. Contrary to our hypothesis, these results indicate that the region in which a planner worked significantly impacted both their connectivity (degree) and influence (betweenness) within the network, while planner experience in emergency preparedness had no significant impact on either.

Another notable characteristic of the network was the difference between the level of communication among planners in the same region and the level of communication across regions. On average, planners communicated weekly to monthly with the other planners in their region, while they communicated only yearly with those outside their region. A few planners, such as G1, A2, and C2, acted as bridges between various regions by communicating regularly with planners in regions outside their own. Planners in some regions, such as A and H, appeared to be well integrated with each other, while planners in regions like D and I were connected to other planners only through their ties with planner G1. In general, there did not appear to be a consistent level of communication among the planners.

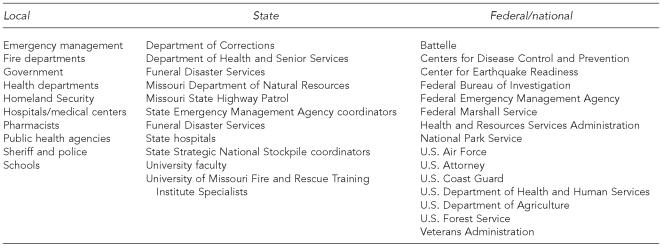

Local and regional planners

Local planners were assigned to one of two regional public health emergency planners: one for regions A, B, F, and H, and the other for regions C, D, E, G, and I. The regional planners were responsible for providing technical assistance to local planners and civic groups. The regional planners also worked with the local emergency planning committees and state emergency management planners in each region and were very involved in SNS planning and exercises.

Figure 4 shows how frequently local planners communicated with regional planners. The links are weighted according to the frequency of communication: the thinnest links represent yearly communication, while the thickest links represent daily communication. Seventy-one percent of local planners communicated at least monthly with their assigned regional planner. More than half of the planners (52%) communicated with both regional planners. For those who communicated with both planners, communication was typically monthly or more with their assigned regional planner and yearly with the unassigned regional planner.

Figure 4.

Frequency of communication between local and regional public health emergency planners

Local and hospital planners

Planners were asked if they worked with any hospital planners and, if so, were asked to identify the hospital planners with whom they worked. Eighteen of the planners (61%) reported working with hospital planners. One hospital planner was identified by half of the 18 planners. No other hospital planner was identified multiple times.

Local planners and local agencies

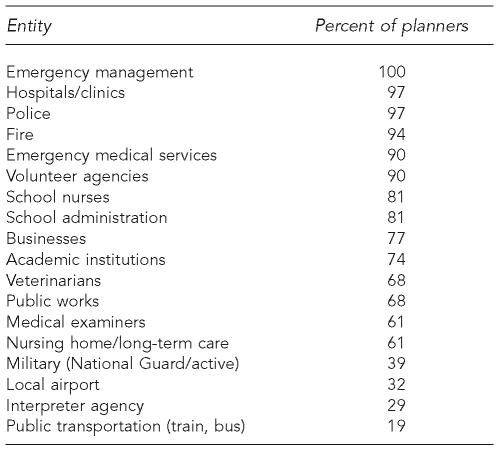

Planners work with a variety of local entities, from academic institutions to fire departments. On average, planners reported working with 12 of the 18 local entities listed on the survey. Not surprisingly, 100% of planners reported working with emergency management. However, only 19% of planners worked with public transportation (e.g., train, bus), and fewer than half of the planners worked with the military (39%), local airports (32%), or interpreter agencies (29%) (Table 2). These lower levels of collaboration were expected as some planners do not have interpreter agencies, public transportation, or military units in their area, and smaller airports have no infrastructure with which to work. Several planners indicated working with other local entities and specified the following:

Churches

Civil air patrol

Elected officials

Federal and state agencies

Federally qualified health centers

Funeral directors

Local emergency planning committees

Local public health agency

Mid-America regional council

Missouri Department of Natural Resources

Pharmacists

There was no significant difference in the number of local entities that planners worked with by region (F=1.00, p=0.46) (Figure 3) or by time employed in emergency preparedness (F=1.39, p=0.26).

Table 2.

Percent of planners working with local entities

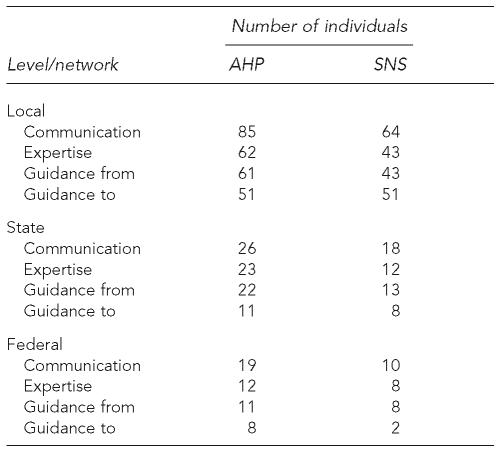

AHP and SNS planner networks

In addition to asking planners about their connections with other local planners, regional planners, hospital planners, and local entities, we asked them specifically whom they communicated with, sought expertise and guidance from, and provided guidance to regarding AHP and SNS planning. These questions were open-ended, allowing local planners to write in names, agencies, or other resources. Table 3 shows the number of individuals planners identified in each area. Overall, 262 unique individuals were identified by at least one planner. Figure 5 shows the affiliations of individuals who were identified by planners. The majority of individuals identified at all levels were affiliated with government agencies.

Table 3.

Total number of individuals identified for each open-ended network question

AHP = All-Hazards Planning

SNS = Strategic National Stockpile

Figure 5.

Affiliations of individuals identified by planners as part of their All-Hazards Planning and/or Strategic National Stockpile network

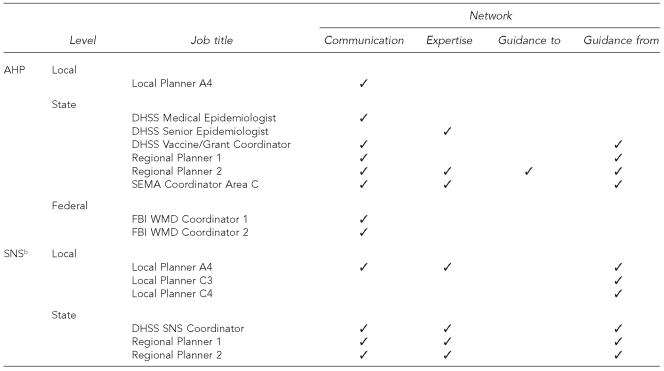

Throughout the nominations, the planners identified a number of individuals repeatedly. We considered those individuals identified by at least 10% of planners in any particular area (e.g., AHP expertise) to be leaders in the Missouri public health emergency preparedness system. Figure 6 lists these leaders by their job title and the area(s) in which 10% or more of the local planners identified each leader. Note that there are few leaders at the federal level, which was expected because planners work on most issues directly with local and state agencies. If contacted, most federal agencies would refer local planners to state agencies unless the planner was from a large metropolitan area.

Figure 6.

Leaders nominated in each network

a Leaders had more than three nominations in an area (.10% of local planners nominated each leader).

b There were no individuals nominated more than three times in any SNS network at the federal level.

AHP = All-Hazards Planning

DHSS = Department of Health and Senior Services

SEMA = State Emergency Management Agency

FBI = Federal Bureau of Investigation

WMD = weapons of mass destruction

SNS = Strategic National Stockpile

DISCUSSION

Planners must work with Local Public Health Agency Administration, Local Emergency Departments, the State Emergency Management Agency, the DHSS, other planners, county commissioners, and volunteer groups. Maybe the most important thing planners do is build relationships with other organizations. (Missouri local public health emergency planner)

As reflected in this quote from one of the planners, our findings show that Missouri's local public health emergency planners spend much of their time and effort seeking and maintaining connections with a wide variety of people and agencies. These connections are crucial in emergency situations such as the power outages described earlier, when planners used their networks to ensure that hospitals had the equipment they needed and that cooling centers were staffed.

Although we found that planners' networks included a large number of individuals in a wide variety of positions, we identified two gaps of interest: (1) the level of regular communication among the local planners was low, and (2) there was a shortage of connections to private-sector individuals in the AHP and SNS networks. While there are no specific guidelines for determining what constitutes an effective public health emergency planning network, addressing these areas could strengthen the Missouri public health emergency preparedness system.

Implications for Missouri State public health preparedness: CERT

To begin addressing the gaps listed previously, we closely examined the communication structure of the local planners and identified a number of important characteristics. For example, the lack of direct connections between planners in Regions B and C was a weakness within the planner network. Region C contains St. Louis, a large metropolitan area, while Region B is the rural area just north of Region C (Figure 1). In the event of a large-scale emergency in the St. Louis area, it is likely that many people from the metropolitan population would travel north to Region B. Without regular direct communication between the local public health emergency planners in Regions B and C, it would be a challenge to coordinate this migration.

We also identified the connections of planner G1 as a critical component of the network because without these links, planners in several regions would be isolated from the rest of the group. Identifying these network characteristics and others allowed CERT to begin building on strengths and addressing weaknesses in the human infrastructure.

CERT will also use these findings to enhance best practices. By learning from those partners who have had success at building relationships with other planners, emergency specialists in their communities, and private-sector individuals, we will develop strategies that all planners can use to strengthen their networks. In addition, understanding the planner networks will improve the efficiency with which CERT and others can distribute information and resources among the planners and their network constituents.

Other implications

Further dissemination of the results of this analysis has the potential to increase overall preparedness across Missouri by giving emergency preparedness and response agencies outside of public health (e.g., fire, law enforcement, emergency medical systems) a better understanding of how the public health system works. Businesses and faith-based organizations could also better connect with public health planners if they understood the structure. Outside Missouri, other state and LPHAs could develop or enhance their preparedness networks by learning from the Missouri structures and strategies.

In addition, although the CDC does not work directly with local planners, having prior knowledge of local public health emergency preparedness networks would allow the CDC to better work with the state to provide critical assets during a public health emergency. Finally, federal agencies that fund preparedness activities could gain further insight into how local preparedness networks function, and thus be able to better support this vital infrastructure through focusing preparedness resources.

Limitations

Cross-sectional studies of relationships have some inherent limitations. First, planners work with so many different individuals that it is nearly impossible to understand their entire networks. Second, relationships tend to be fluid. While we believe the information we collected allows a good general understanding of Missouri public health planner networks, it is a snapshot, and relationships will certainly change as time passes. Third, our results do not provide information about the quality of the relationships but rather the composition of planner networks and the frequency of communication between planners and others.

CONCLUSION

Use of a systems approach and social network analysis facilitated an understanding of the composition of public health emergency planner networks in Missouri. While there are several articles describing how emergency response networks have responded to emergencies,3,11 we only identified one study that described predisaster networks of emergency responders.21 As a result, very little is known about the characteristics of effective, or even existing, emergency planning and response networks. Our study contributes a first look at the composition and structure of a statewide system of local-level public health emergency planners.

We believe these findings are just the beginnings of understanding the complexity of relationships that go into public health emergency preparedness. By strategically using the information gleaned from this study and future studies of emergency preparedness systems, we have the potential to improve emergency preparedness and response so that future threats will not reveal the sorts of structural weaknesses we have seen in the past.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Nancy Bush for her major role in this project. In addition, the authors offer sincere thanks to Hope Woodson, Greg Evans, Ryan Burke, Stephanie Herbers, Dan Morris, and Angela Recktenwald for their helpful ideas and comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Footnotes

Funding for this study was provided by the Center for Emergency Response and Terrorism at the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services.

REFERENCES

- 1.Perry RW, Lindell MK. Preparedness for emergency response: guidelines for the emergency planning process. Disasters. 2003;27:336–50. doi: 10.1111/j.0361-3666.2003.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auf der Heide E. Community medical disaster planning and evaluation guide. Dallas (TX): American College of Emergency Physicians; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapucu N. Interorganizational coordination in dynamic context: networks in emergency response management. Connections. 2005;26:33–48. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trochim WM, Cabrera DA, Milstein B, Gallagher RS, Leischow SJ. Practical challenges of systems thinking and modeling in public health. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:538–46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cwiek MA, Johnson JA, Ledlow GR. At the front lines of the war on terrorism: international business must partner with communities for preparedness initiatives. Proceedings of the 2004 Global Business and Technology Association; Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwait J, Valente TW, Celentano DD. Interorganizational relationships among HIV/AIDS service organizations in Baltimore: a network analysis. J Urban Health. 2001;78:468–87. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luke DA, Harris JK. Network analysis in public health: history, methods, and applications. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:69–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKinney MM, Morrissey JP, Kaluzny AD. Interorganizational exchanges as performance markers in a community cancer network. Health Serv Res. 1993;28:459–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. House of Representatives. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2006. A failure of initiative: final report of the select bipartisan committee to investigate the preparation for and response to Hurricane Katrina. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Statement of H. Dan O'Hair, PhD: hearing before the Research Subcommittee of the House Science Committee. 109th Congress, 1st Session; 2005 Nov 10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen MJ. State-level emergency response to the September 11 incidents: the role of New Jersey's Department of Environmental Protection. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 2003;11:78–85. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehra A, Smith BR, Dixon AL, Robertson B. Distributed leadership in teams: the network of leadership perceptions and team performances. Leadership Quarterly. 2006;17:232–45. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morton SC, Dainty ARJ, Burns ND, Brookes NJ, Backhouse CJ. Managing relationships to improve performance: a case study of the global aerospace industry. International Journal of Production Research. 2006;44:3227–41. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krackhardt D, Hanson JR. Informal networks: the company behind the chart. Harvard Bus Rev. 1993;71:104–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGregor J. Game plan: first find the leaders. BusinessWeek online [serial on the Internet] 2006. Aug 21, [cited 2006 Oct 1]. Available from: URL: http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/06_34/b3998437.htm.

- 16.Center for Emergency Response and Terrorism. Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services; 2006. Regional public health emergency planning and preparedness: scope of work. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Health protection goals: people prepared for emerging health threats. [cited 2006 Dec 29]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/osi/goals/preparedness.html.

- 18.Department of Homeland Security (US) FEMA independent study program. [cited 2007 Jan 4]. Available from: URL: http://www.training.fema.gov/emiweb/Is/crslist.asp.

- 19.Batagelj V, Mrvar A. Networks/Pajek: program for large network analysis (computer program) [cited 2007 Jan 4]. Available from: URL: http://vlado.fmf.uni-lj.si/pub/networks/pajek.

- 20.SPSS, Inc. SPSS: Version 13.0 for Windows. Chicago: SPSS Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi SO, Brower RS. When practice matters more than government plans. Administration & Society. 2006;37:651–78. [Google Scholar]