In an effort to balance the traditional concern with individual rights in medical ethics with the communitarian values of public health, members of the Public Health Leadership Society proposed a code of ethics for public health in 2001 that was later adopted by the American Public Health Association (APHA), the National Association of Local Boards of Health, and other organizations. In endorsing the Code, the APHA urged public health agencies to adopt it as their own. This is the story of how one local health department adapted and applied the Public Health Code of Ethics to local public health practice.

BACKGROUND

In 2002, the APHA endorsed the Public Health Leadership Society's newly developed Public Health Code of Ethics and urged public health agencies nationwide to adopt it as their own. The Code observed that “the concerns of public health are not fully consonant with those of medicine … [and] thus … cannot simply translate the principles of medical ethics to public health.”1 Medical ethics relies on the standard cluster of individual rights that are well established in our moral and political tradition (e.g., autonomy, confidentiality, property rights) and incorporates a strong sense of respect for the diversity of values and beliefs we find in our communities. But such rights of individuals are in inherent tension with the communitarian values that emerge from the nature of public health, namely, “what we, as a society, do collectively to assure the conditions for people to be healthy.”2 The Public Health Code of Ethics therefore acknowledges these individual rights and weighs them against the values of population health and empowerment of groups of individuals.

Soon after its adoption by these national organizations, the Mahoning County District Board of Health in Youngstown, Ohio, made the new Code required reading for new employees during their orientation. However, to integrate the Code into the organizational policies and practices, we felt the need to adapt the new Code to improve the organization's ethical practice of public health by:

Increasing transparency in decision making, so that even when stakeholders disagree with a controversial decision, they understand how it was made;

Guiding the exercise of the Board of Health's police powers in its regulatory programs; and

Building ethically based decision-making skills and competency among board members and staff.

An employee code of conduct focused on individual ethical behavior had been adopted by the Board of Health some years earlier; however, it lacked the aspirational language of public health values articulated in the Public Health Leadership Society work.1 We recognized a need to stake out a position somewhere between the individually focused prescriptions of our employee code of conduct and the more abstract language of the Code.

INITIATIVE SUMMARY

In 2004, we approached the director of our local university-based ethics center (Palmer-Fernandez, one of the authors) for assistance in drafting a new code. While Palmer recognized some difficulties in creating an inclusive organizational code based on action guides, he knew that other professions had successfully implemented organizational codes of ethical conduct that—without prescribing specific organizational decisions—outlined desirable paths to follow when concrete actions were required to address situations involving conflicting commitments and interests. As another ethicist said of the Public Health Code of Ethics, it cannot be “an ethics prescription for practitioners seeking specific action-guides for concrete decisions … it does not tell us how to balance … commitments when they are in conflict; it does not tell us what we ought to do in particular cases.”3 Palmer came to realize that what the Board of Health needed was not a code of conduct for the individual public health professional, but rather a code of practice for the entire organization.

In drafting such a code, he asked questions about institutional integrity, the role of policy and administrative decision making, and how the purposes of the institution are specified (e.g., in vision and mission statements) and then applied to practice. He reviewed many of the codes of conduct in medicine, law, engineering, nursing, social work, and law enforcement. He also consulted with academic colleagues with expertise in organizational ethics and reviewed guidelines available for drafting codes of corporate ethics from the Society for Human Resource Management and others.

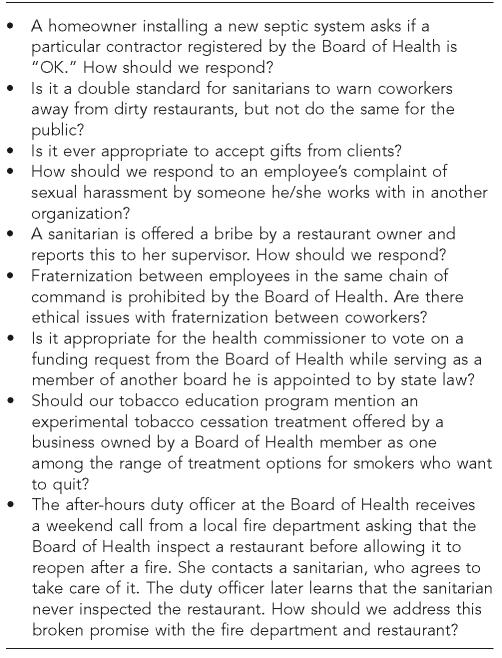

Later in 2004, Palmer convened two focus groups, one consisting of bargaining unit staff (e.g., nurses, sanitarians, health educators, secretaries) and the other comprising management and board members. The purpose of these focus groups was to explore the basic values and principles of public health as conceived by practitioners; gather examples of the ethical challenges staff and management face, both internal to the Board of Health and in their relations with the public they serve; challenges of allocation and priority setting; and the professional practice of public health itself. Most of the information gathered from these focus groups was compatible with the values and principles contained in the Public Health Code of Ethics, as well as the values and beliefs underlying that Code (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Examples of potential ethical challenges gathered from Board of Health focus groups

Following these reviews and meetings, Palmer created a document titled “Our Shared Responsibilities: Code of Organizational Ethics.”4 This Code was reviewed and accepted by the Board of Health in the fall of 2005. It incorporates several strategies to help the Board of Health address a wide range of institutional ethical issues.

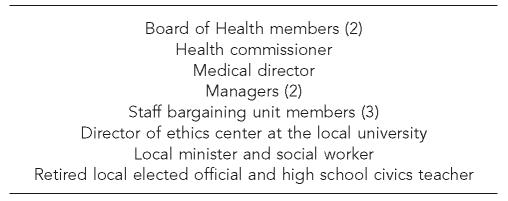

Recognizing that no single set of prescriptions could cover even a modest range of practice decisions, the Code of Organizational Ethics called for the creation of an Ethics Advisory Committee (EAC) with representation from staff, management, and the community (Figure 2). The EAC's main purpose was to assist the Board of Health and staff in making ethical decisions by applying the organization's basic values as specified in the Code of Organizational Ethics. The EAC was intended to provide a safe zone for anyone in the organization to discuss ethical concerns confidentially, without fear of retribution, and with the certainty of a sympathetic hearing. Other important purposes served by the EAC are:

To develop the ability to identify an ethical issue in the practice of public health and in the Board of Health;

To provide members of the Board of Health and staff with a decision-making process aimed at resolving disagreements on actions by the Board of Health and issuing recommendations on potential actions;

To serve as a consultative body for discussion and recommendations; and

To educate the Board of Health and staff on the ethical practice of public health.

Figure 2.

Ethics Advisory Committee composition

Recognizing that additional training was needed for EAC members to fulfill their duties, the university ethics center drew on its endowment to bring in a consultant with expertise in organizational ethics. During a two-day period in fall 2005, Charlotte McDaniel, an ethicist from Emory University, reviewed and advised on the code adopted by the Board of Health, and offered training to members of the EAC using a case study she tailored to the local health department setting. McDaniel asserts, “Ethics cases provide fruitful responses in the evaluation … of ethics training, in-service education on ethics theories, or assessing employees' abilities to implement critical analysis on ethics.”5

OUTCOME AND EVALUATION

In this section we present a case in which the Code of Organizational Ethics was used to resolve a community concern related to a Board of Health ruling.

As one group of ethicists has observed, “The state's use of its police powers for public health raises important ethical questions, particularly about the justification and limits of governmental coercion and about its duty to treat all citizens equally in exercising these powers.”6 This case is a summary of one of the first concerns that was brought to the EAC, in this instance because of a complaint by a community member that public health was using coercion to support a practice that was neither transparent nor fair.

An application of the Code of Organizational Ethics

This case involved a community's right to know and the Board of Health's exercise of its duty to compel property owners to connect to privately installed sewer lines. Prior to reissuing an order to a group of homeowners with septic systems to connect their homes to a newly installed sewer line, the Board of Health asked the EAC for a recommendation. The committee was provided the following background information to help inform its discussion.

State law allows real estate developers to ask county commissioners to assess part of the cost of installing sewer lines servicing new real estate developments to the property owners along the route of the newly installed sewer lines. These so-called 307 assessments must be paid to the sanitary engineer when the property owner connects to the new sewer. The sanitary engineer then reimburses the developer. With the exception of a few large publicly financed sewer projects, most new sewer lines installed in the Board of Health's jurisdiction in recent years have been financed by private developers and 307 assessments.

State law also requires that property owners abandon their septic systems and connect to sewer lines when they become accessible. Local boards of health are assigned the duty by state law to compel property owners to connect. But state law is silent about when these sewer connections must be completed; by local regulation of the Board of Health, this deadline has been set at 180 days.

In the case that prompted the Board of Health to ask for a recommendation from the EAC, when the Board of Health was presented by the county sanitary engineer with a list of property owners accessible to a newly installed private sewer, it issued orders to these homes to connect within 180 days as required by its own regulation. After receiving these orders, several homeowners objected to the lack of public notice of the developer's intention to install sewer lines and to some of the costs that the sanitary engineer had agreed to assess the homeowners.

After hearing the homeowners' objections, the Board of Health agreed to stay its connection orders and asked its EAC to address these specific questions:

What redress should the Board of Health seek for these homeowners who were not afforded the opportunity to review and comment on their 307 assessments?

How does the Board of Health reconcile two public “goods”—the abatement of pollution and disease risk that comes from installing sewers AND property owners' right to know about governmental decisions that impose financial obligations on them—the next time it is required to order residents to connect to privately installed sewers?

EAC recommendations

In reviewing relevant sections of state law, the committee observed that county commissioners “may make such rules and regulations as may be necessary to administer” the 307 assessment process. The committee recommended that the Board of Health advise county commissioners to adhere to the following process before granting permission to a developer to construct private sewer lines:

The sanitary engineer will hold a public meeting and provide written notice of the meeting to property owners along the proposed route and to the local political subdivision.

The developer or developer's representative will be required to appear at the meeting and present the sewer construction plan.

Before authorizing collection of 307 assessments from homeowners, the sanitary engineer will hold another public meeting at which the developer will appear at the meeting to present actual costs of installing the sewer lines.

The committee also recommended that the developer involved in the present case appear before the Board of Health in a public session.

The Board of Health accepted the recommendations of the EAC, as did the county commissioners. The developer appeared before the Board of Health to explain his costs at a meeting with affected homeowners and local elected officials present. The Board of Health then reinstated its connection orders to these homes. The county commissioners subsequently enacted the requirement for property owner notification and public hearings for all 307 assessments.

DISCUSSION

As the Principles of the Ethical Practice of Public Health observe, “The need to exercise power to ensure health and at the same time to avoid the potential abuses of power are at the crux of public health ethics.” Further, the Principles admonish us that “there remains the need to pay attention to the rights of individuals when exercising the police powers of public health.”1 This article reports the creation of a Code of Organizational Ethics deriving from the Public Health Leadership Society's Public Health Code of Ethics, from review of other organizational codes, and from focus group input of practicing public health workers in a variety of fields. We have applied this Code to real problems in public health practice, and found its structure—particularly its use of an EAC—to be helpful in insuring the dutiful, yet restrained exercise of public health police powers. By involving community members and staff in the EAC, we have attempted to make our decision-making processes more transparent to our staff and the community.

Although the involvement of an EAC may not necessarily change the outcome of our decision-making process, its recommendations, when accepted by the Board of Health, can serve to increase confidence in the ethical soundness of its course of action. In the case study presented here, we believe that the Board of Health's decision may have resulted in a higher rate of property owner compliance with orders to connect to sewer lines; no further legal action was required to exact compliance from the property owners affected by this case, as has often been the case with 307 assessments prior to the new requirement for public notice and meetings.

The EAC has subsequently deliberated other issues, such as: conflict of interest in voting as a member of a public body; the applicability of child neglect reporting laws to caregivers of lead-poisoned children; the rationing of flu vaccine; and the duty to protect or disclose a homeowner's drinking water test results. None of the issues we have deliberated so far could be described as requiring immediate action. We acknowledge that subjecting some issues in local public health practice to an ethical review process as we have described in this report may be impractical in an emergency or disaster situation, when the consequences of our decisions may have an even greater impact on the rights of individuals and populations in the community. In such situations, the Board of Health's Organizational Code of Public Health Ethics serves as a present reminder of our duty to adhere to organizational public health values as we choose the most desirable path to follow for addressing emergent situations involving conflicting commitments and interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Public Health Leadership Society. Principles of the ethical practice of public health, version 2.2 (Public Health Leadership Society website) [cited 2006 Oct 23]. Available from: URL: http://209.9.235.208/CMSuploads/PHLSethicsbrochure-40103.pdf.

- 2.Institute of Medicine; Committee for the Study of the Future of Public Health, Division of Health Care Services. Washington: National Academies Press; 1988. The future of public health. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olik RS. Codes, principles, laws and other sources of authority in public health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10:88–9. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200401000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahoning County District Board of Health. Our shared responsibilities: Code of Organizational Ethics. [cited 2007 Jan 2]. Available from: URL: http://www.mahoning-health.org/about-ethics.htm.

- 5.McDaniel C. Organizational ethics: research and ethical environments. Burlington (VT): Ashgate; 2004. p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Childress JF, Faden RR, Gaare RD, Gostin LO, Kahn J, Bonnie RJ, et al. Public health ethics: mapping the terrain. J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30:170–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2002.tb00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]