Abstract

Background:

Poor follow-up rates greatly diminish the validity of prospective and long-term studies. Therefore, locating patients is of critical importance. This is especially true in populations treated during childhood because addresses will change several times in intervening years. Recent publications have reported new strategies for patient location. The purpose of this study is to test an algorithm proposed by King et al., as well as other search methods, using a cohort of patients treated for clubfoot in childhood

Methods:

The study population included 126 patients with clubfeet treated between 1950 and 1967. We followed the search algorithm proposed by King et al. In addition, we used state driver's license records, Reunitetonight.com, and Intelius.com. Patients were considered to be found when they returned a postage-paid reply letter or were contacted by phone.

Results:

Using web pages recommended by King et al. we located 26 of 126 (21 percent) patients. Operator directory assistance failed to locate any patients not located by free internet sources. Additional websites had varied results. State driver's license records found 25 patients. Reunitetonight.com found none with thirty attempted. The best search engine was Intelius.com which located 68 out of 126 (54 percent) patients.

Conclusion:

The algorithm proposed by King et al. is not effective for long-term follow-up studies of pediatric populations. Intelius.com is worth the small fee charged ($22.45) as it was the most effective method of locating patients.

INTRODUCTION

The nature of pediatric orthopaedics requires that injuries and congenital deformities be corrected using current best practices. The musculoskeletal system of children is very resilient and will generally return to a normal level of function shortly after treatment.1 It is only after decades of use of a slightly abnormal structure that the advantages of one treatment method over another will become apparent.1–7 For this reason, long-term follow- up studies are essential to improving the clinical practice of pediatric orthopaedics.4–9

One of the primary obstacles in any long-term follow- up study is the difficulty of locating patients.5 This is especially true for a population treated in childhood. The patients and their parents may have changed addresses several times in the intervening years. Marriage and divorce often result in name changes which further complicate attempts to locate subjects. Other patients may have died since the last patient contact.

Reliable methods for locating subjects for long-term follow-up studies have been reported in the last few years.5, 10–12 However, there is increasing interest in protecting private patient information, and all methods must meet the requirements of the institution's Institutional Review Board (IRB). Few studies have examined the relative effectiveness of free internet search engines, and to our knowledge no studies have evaluated any subscription-based internet search engines.

After attempting to locate patients for a 50-year follow- up of idiopathic clubfoot, using only information available in the medical record, we began investigating alternative patient location methods. We hypothesized that the algorithm published by King using free internet search engines would enable us to easily locate a large portion of our study group.10 In addition, we evaluated the effectiveness of searching state driver's license records, telephone operator assistance, and the internet search engine Intelius.com, which requires a paid subscription.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

We attempted to locate 126 patients who were treated for clubfoot at our institution between 1950 and 1967. All clubfeet were treated with the serial casting method described by Ponseti.13 Results for this same study population have been reported previously. Ninety-eight patients were located for the 1980 study, and 61 were located for the 1995 study.4,9 Seventy patients participated in the 1980 study and 45 patients participated in the 1995 study. The study population is now between the ages of 38 and 55.

Location Methods

Identifying information, including middle name, social security number, birth date, and last known address, were extracted from the patient's hospital record. When present in the hospital record, the same information was obtained for the patient's parents.

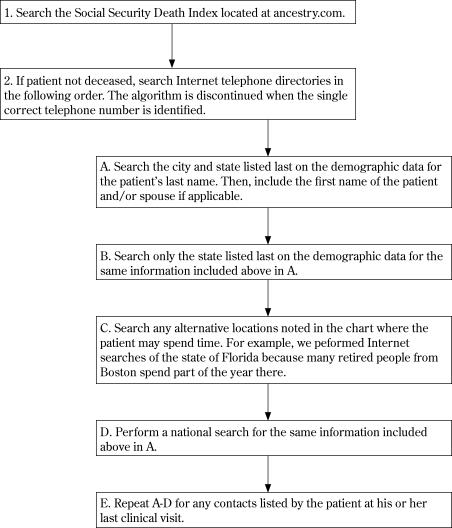

Using this information, we followed an algorithm published by King that utilizes free internet search tools. According to this algorithm, we first searched the Social Security Death Index as available on Ancestry.com. This has been shown to be a moderately effective (83 percent success rate) method of identifying deceased individuals.11 Next, we searched for patients through a number of internet phone and address directories including anywho.com, people.yahoo.com, superpages.com, switchboard.com, whitepages.com, and whowhere.com. We first searched the last known city and state, followed sequentially by the state only, other locations mentioned in the chart, and a national search. If the patient was still not located, we searched for anyone else mentioned in the chart using the same algorithm (Figure 1). We used all search engines to try to locate each patient, regardless of whether the patient had been correctly located by a previous search engine.

Figure 1.

Internet search algorithm. From: KING: J Bone Joint Surg Am, Volume 86-A(5). May 2004:897-901.

In addition to the search engines specifically named by King, we also tried several other search mechanisms including other internet search engines, driver's license records, and directory operator assistance. We used the free internet search engine Reunitetonight.com and the paid internet search service Intelius.com using the same search method described above. Intelius.com was used to attempt to locate all patients, regardless of whether the patient had been correctly located by a previous search engine. Reunitetonight.com was only used in attempts to locate thirty patients. We discontinued searching with Reunitetonight.com because it failed to correctly locate any of the first 30 patients. For those patients not located by these internet search engines, we contacted operator directory assistance in the city corresponding to the patient's last known address. The last known city and state, and the names of any relatives mentioned in the chart, were given to the operator who would then provide any likely addresses and telephone numbers. We also used the patients' names, birth dates, and social security numbers to search the state driver's license records.

When a reasonable address was identified, a letter was sent to the patient inviting them to participate in the study. If no reply was received within two weeks of sending the first letter, we attempted to contact the patient over the phone. The patient was considered located when they returned a reply letter or were contacted by phone.

Results

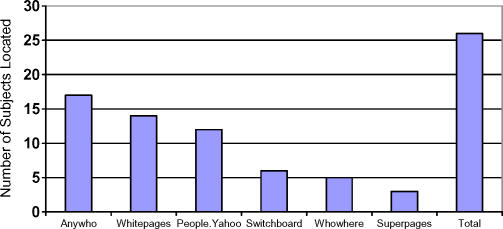

A total of 26 patients were located using free internet search engines as described by King. The individual search engines yielded variable results (Figure 2). Anywho.com was the most successful, correctly locating 17 out of the 126 possible subjects. Whitepages.com and People.yahoo.com provided similar results, correctly locating 14 and 12 subjects, respectively. Switchboard.com was able to locate six subjects. Whowhere.com located five subjects, while Superpages.com located three subjects. Ancestry.com confirmed five patients to be deceased. Two of these deaths were corroborated by hospital records. There were very few patients for whom correct contact information could be extracted directly from the medical record, and all of these patients were also correctly located using the King algorithm.

Figure 2. Results with King's Algorithm.

Results obtained with King's Algorithm. The number of correctly located patients is listed for each free internet search engine. The total located using the algorithm is also shown. Each web page ends in ".com".

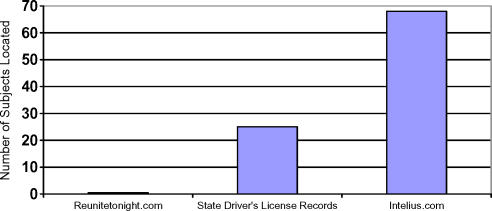

Alternative searches not included in the King algorithm displayed mixed results (Figure 3). Reunitetonight.com was unable to locate any of the 30 patients for which it was used. Operator directory assistance was used only on patients not located by any of the free internet search engines, and was unable to successfully locate any of the 57 patients. Intelius.com was the most useful, correctly locating 68 of 126 subjects. State driver's license records were able to locate 25 of 126 subjects, including one patient who was not located by any other method. Combining results from all internet search engines, we were able to locate 48 percent of female patients and 62 percent of male patients.

Figure 3. Results of Alternative Search Methods.

Results of Alternative Search methods. Intelius.com proved to be the most efficient and most effective method for locating patients.

DISCUSSION

Long-term follow-up studies are often hampered by difficulty locating and contacting patients. Patient contact is especially difficult when the subjects were treated in childhood because the patients' names, addresses, and telephone numbers may have changed many times in the intervening years.

The amount of readily available information on the internet provides an opportunity for better and faster patient location. King reported 100 percent success locating patients five years after total knee arthroplasty using free internet search engines.5 Utilization of these services does not require special IRB approval because they are publicly available and do not provide the user with any protected information. Our study found King's method was much less effective at locating patients who were treated in childhood. The King algorithm only located 26 patients out of the 126 total patients (21 percent). The difference in results between our study and King's is most likely a function of the length of time that had elapsed since the patients were last seen. King's study was looking for patients lost to follow-up only five years after total knee arthroplasty, compared to a 50-year follow- up in our study. The arthroplasty patients were also older and likely more established when initially treated. Older patients would be less likely to change names or addresses after treatment than patients who were initially treated as children.

The free internet search engines are also limited because they do not provide cellular phone numbers or unlisted numbers. As more and more people rely on their cellular phone as their primary telephone and eliminate traditional land lines, such search databases may become less and less effective.14

We found that utilizing multiple free internet search engines did improve the rate of locating patients. All patients for whom the chart contact information was correct were located using free internet search engines. The most successful single free search website was Anywho.com which located 17 patients, while a total of 26 patients were located by the entire battery of free people-search websites.

We attempted to utilize operator directory assistance to locate patients who were not located using the free internet searches. However, this method was abandoned after attempts were made on 57 different subjects and none of them were successfully located. It appears that the operators do not have access to, or cannot provide, better information than what is available on the internet for free.

Ancillary methods, such as searching the state driver's license records, may improve the ability to locate patients. In our study, this was almost as successful as the use of multiple free internet searches. However, this database contains no information about patients who have moved out of state. Also, because this database contains other protected information about the patient, separate IRB approval is required.

The most effective method for locating patients was the Intelius.com website. Intelius.com was able to locate 68 patients, including all of the patients who were located by the free search engines. Intelius.com also offers a social security number search which provides information regarding relatives, property ownership, lawsuits and other information. While the social security number search would be very helpful in narrowing down a list of people with the same name, we did not use this particular option because it revealed excessive and unnecessary information concerning the subjects' personal lives. Use of the engine for these purposes would likely not be allowed by an Institutional Review Board. Intelius.com was both highly effective and highly efficient and is recommended for locating subjects for long-term follow-up studies of pediatric populations.

Though we selected Intelius.com, there are a number of other fee-for-service search engines available on the Internet. We made no attempt to evaluate all search engines, and other web sites may offer similar or even improved results.

The rapidly changing nature of the Internet may be both beneficial and detrimental to future patient identification attempts. Because the information can be updated relatively easily, contact information on the internet may actually be much more up to date than information in traditional telephone directories. On the other hand, web sites identified in this article may also be subject to frequent changes in cost, may fail to be updated regularly, or may disappear altogether.

In conclusion, search engines readily available on the internet are an excellent tool for locating patients. Free search engines may be useful for relatively short-term follow-up, but we found that search engines requiring a small fee were much more successful at locating patients for longer term follow-up. The efficiency and increased efficacy of the fee-for-service internet search was well worth the added cost.

Footnotes

Investigation performed at The Ponseti Center for Clubfoot Treatment, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa

The authors indicate that they do not have any relationship with any of the people-search services discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Huber H, Dutoit M. Dynamic foot-pressure measurement in the assessment of operatively treated clubfeet. J Bone J Surg Am. 2004;86:1203–1210. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200406000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson J, Puskarich CL. Deformity and disability from treated clubfoot. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;10:109–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutchins PM, Foster BK, Paterson DC, Cole EA. Long-term results of early surgical release in club feet. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:791–799. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B5.4055883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper DM, Dietz FR. Treatment of idiopathic clubfoot. A thirty-year follow-up note. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1477–1489. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199510000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JS, Watts HG. Methods for locating missing patients for the purpose of long-term clinical studies. J Bone J Surg Am. 1998;80:431–438. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199803000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Spratt KF, Peterson KK, Spoonamore MJ, Ponseti IV. Health and function of patients with untreated idiopathic scoliosis: a 50-year natural history study. JAMA. 2003;289:559–567. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.5.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morcuende JA, Meyer MD, Dolan LA, Weinstein SL. Long-term outcome after open reduction through an anteromedial approach for congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:810–817. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199706000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyer DW, Mickelson MR, Ponseti IV. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Long-term follow-up study of one hundred and twenty-one patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:85–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laaveg SJ, Ponseti IV. Long-term results of treatment of congenital club foot. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King PJ, Malin AS, Scott RD, Thornhill TS. The fate of patients not returning for follow-up five years after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone J Surg Am. 2004;86:897–901. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200405000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyle CA, Decoufle P. National sources of vital status information: extent of coverage and possible selectivity in reporting. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131:160–168. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schootman M, Jeffe D, Kinman E, Higgs G, Jackson-Thompson J. Evaluating the utility and accuracy of a reverse telephone directory to identify the location of survey respondents. Annals of Epidemiology. 2005;15:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ponseti IV, Smoley EN. Congenital club foot: the results of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1963;45:261–275. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Almanac & Book of Facts. 2005. p. 398.