Abstract

To evaluate the potential use as a therapeutic agent for osteoporotic fractures, we examined the effects of intermittent administration of parathyroid hormone on fracture healing in ovariectomized rats. At three months post-ovariectomy, bilateral tibial shaft fractures were induced and stabilized by intramedullary nailing with Kirschner-wires. Saline, 17-estradiol, or recombinant human PTH(1-84) was given once a day for 30 consecutive days during fracture healing. Fracture healing was assessed by morphometric and mechanical analysis of fracture callus. Intermittent parathyroid hormone administration increased the morphometric and mechanical parameters in a dose-dependent manner. 17-estradiol, a bone-resorption inhibiting agent, did not offer advantage in terms of fracture healing in ovariectomized rats. Our findings suggest that intermittent parathyroid hormone administration may benefit osteoporosis and fracture.

Osteoporosis is a major health care problem in the older population and frequently leads to orthopedic treatment for fracture repair. Drugs to treat osteoporosis can be classified according to the response of the bone. They either stimulate bone formation or inhibit bone resorption. Among the bone-forming agents, intermittent parathyroid hormone (PTH) administration has anabolic effects on bone of animals5–7,14,15,18,19,33,34 and humans1,21–24,32. PTH can increase bone mass at all four envelopes: cancellous, endocortical, intracortical, and periosteal. This anabolic action of PTH does not require previous stimulation of bone resorption induced by ovariectomy12,26,27.

Fracture healing involves a complex pattern of interactions between local and systemic regulatory factors. The processes of normal and abnormal fracture healing, and the various factors affecting them have been widely studied. Hormones may play a substantial role in bone repair but there is lack of uniformity in the presentation of data. Many authors presume aging decreases the quality of fracture repair, and an age-related decline in the capacity for fracture repair has been noted2,4,8,25,29. However, the question of impaired fracture healing in osteoporotic patients, and the role of estrogen deficiency in its etiology still remains unclear.

Traditionally, PTH is well known for its catabolic action on the skeleton. To date, we are not aware of any study investigating the influences of exogenous PTH administration on fracture healing which is essentially an anabolic process. The ovariectomized (OVX) rat model causes changes in bone that resemble most of the characteristics of human postmenopausal bone loss9,13,16,17. It is now generally accepted that OVX rats should be used as the animal model for screening new agents for osteoporosis therapy. The present study was designed to compare fracture healing in normal and OVX rats, and to examine the effect of intermittent administration of PTH on fracture healing to evaluate its potential use as a therapeutic agent for osteoporotic fractures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental protocols

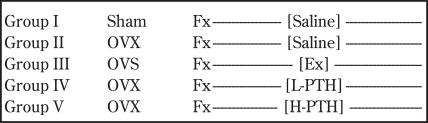

All animal studies were carried out with the approval of the institutional review board. A total of 75, four month-old mature female Sprague-Dawley rats were used. The mean and standard deviation of weight was 256 7 grams. The animals were randomly divided into 5 groups and weight matched. They were then treated according to the protocol shown in Figure 1. Fifteen animals underwent a sham operation and served as intact controls (Group I). Bilateral ovariectomies were performed from a dorsal approach in the remaining 60 animals in the other 4 groups (Groups II, III, IV, and V). Groups of four animals were housed in a cage kept at a constant temperature and humidity. They had free access to a standard diet of rat chow and water.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol. Sham = sham operation, OVX = ovariectomy, Fx=fracture, E2 = 17 beta-estradiol, L-PTH = low doses of PTH, H-PTH = high doses of PTH

At three months post-surgery, all animals in the five groups underwent bilateral controlled tibial shaft fractures under intraperitoneal anesthesia with ketamine hydrochloride and xylazine at doses of 50 mg/Kg and 25 mg/Kg body weight, respectively. The desired fracture patterns were created using a modified technique of Bak and Andreassen2,3. Both lower extremities were shaved and prepped with povidone-iodine solution. A hole was made 4 mm proximal and 2 mm medial to the tibial tuberosity percutaneously using a 20-gauge needle. The needle was driven into the medullary canal. By rotating the needle, the canal was reamed to just proximal to the ankle joint allowing for the wire to seat and prevent it from perforating the cortex. A fracture was then created 5 mm above the tibiofibular junction by three-point bending using specially designed forceps with blunt jaws. The fractures were immediately stabilized by closed intramedullary nailing using a 0.73 mm Kirschner wire (Zimmer Co., Warsaw, Indiana, USA) through the prepared hole. Rotation was checked by comparing the alignment of the foot and the thigh. Radiographs were taken after surgery to document the fracture configuration and wire placement. A satisfactory fracture pattern was defined as transverse mid-shaft fracture without obvious angulation, comminution, or displacement, and with intramedullary fixation bridging the fracture. After recovering from the procedure, the animals were allowed to resume free activities and weight bearing in the cage.

Every day from the day of fracture surgery on, saline, estrogen, or PTH was administered to rats once a day by subcutaneous injection for 30 consecutive days: saline solution (a volume equal to the volume of the drugs given) in Group I and Group II, 17 b-estradiol (30 µg/Kg) in Group III, low doses of recombinant human PTH(1-84) (15 µg/Kg) in Group IV, and high doses of recombinant human PTH(1-84) (150 µg/Kg) in Group V. Recombinant human PTH(1-84) was commercially available from Korean Green-Cross Pharm. Corp. (Seoul, Korea) and 17-estradiol from Sigma Chemical Corp. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Animals were killed by CO2 inhalation at 30th day post-fracture surgery, and the success of the ovariectomy was confirmed by absence of any residual ovarian tissue at sacrifice. Healing left and right tibiae were harvested after the hindlimbs were disarticulated at the knee joints. The soft tissues and fibulae were carefully cleared, preserving the integrity of callus. The intramedullary Kirschner wires were taken out through the original entrance. All tibiae of the left side were examined by morphometric analysis of periosteal callus (quantitative analysis of fracture healing), and all right tibiae were tested mechanically (qualitative analysis of fracture healing), respectively.

Morphometric measurement of fracture callus

For the decalcified section, all left tibiae were fixed in 5% formalin, decalcified, and embedded in paraffin. Serial 3-m thick sections were cut through the longitudinal axis of the tibia and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin. Three central slices of each series showing the maximal width of the medullary cavity were selected for morphometric analysis. The evaluation was aided by a fully automated computerized image analysis system (Media Cybernetics Corp., Silverspring, Maryland, USA) attached to the light microscope. The callus area was defined as the area between the original cortex and the thin outer bridging bone shell. The length of the callus was determined by the distance from distinct lifting of periosteal tissue to a distinct "normalization", and the width of the callus was measured in its widest part. Trabecular bone per tissue area inside the callus, and the quantitated surface area of the trabecular bone in the callus were also assessed. Both sides of the callus were assessed per section, and the obtained values were averaged and plotted.

Mechanical measurement of fracture callus

For mechanical testing, all right tibiae were stored in gauze soaked in normal saline solution at -20°C until needed. All mechanical testing was done within forty-eight hours of death. All bones were similarly oriented in a material testing machine (Instron LTD WYCOMBE, Buckinghamshire, UK) and the area to be tested defined as the medial aspect of the fracture callus. A custom jig ensured consistent alignment of the bone axis with the axis of the testing machine. The bones were placed on two rounded bars separated a distance of 15 mm, and deflected by lowering a third centered bar on the healed fracture site at a constant rate of 1 mm/min until failure. The load-deflection curves were digitized and immediately analyzed. The following parameters were calculated: ultimate load, deflection until ultimate load, absorbed energy until ultimate load, and ultimate stiffness. To normalize the raw data to compensate for differences in bone mass and cross-sectional area, the fracture surface induced by mechanical testing was further studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Internal and external diameters in the load direction and perpendicular to it were obtained using a computer image analysis system. Cross-section was approximated to a thick-walled elliptical tube, and the ultimate stress was then calculated from the bending moment and the second moment of area2,3,17.

Measurements of all parameters are expressed as group means ± SD. Significant differences between group means (p < 0.05) were determined from analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc multiple comparisons using Tukey's Studentized Range test for inter- group differences.

RESULTS

Of 75 rats used for this study, 12 were eliminated; five rats died during surgery, and technical failure of the fracture procedure or intramedullary nailing resulted in another seven animals being eliminated from the experiment. There were no postoperative infections. In the remaining 63 rats, the intramedullary fixation maintained axial alignment of the fracture without interfering with the formation of external fracture callus.

Morphometric measurements of fracture callus (Table I)

TABLE I. MORPHOMETRIC MEASUREMENTS OF TIBIAL FRACTURES IN THE RAT. (MEAN ± SD).

| Group I (n=13) |

Group II (n=14) |

Group III (n=12) |

Group IV (n=13) |

Group V (n=11) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Callus length (mm) |

8.92 ± 2.38 | 10.08 ± 2.34 | 10.20 ± 2.02 | 10.45 ± 2.04 | 11.27 ± 2.07 |

| Callus diameter (mm) |

0.91 ± 0.21 | 1.11 ± 0.17 | 1.08 ± 0.19 | 1.41 ± 0.27 a,b,c | 1.45 ± 0.34 a,b,c |

| % Trabecular bone in callus (%) |

92.04 ± 2.80 | 58.44 ± 5.24 a | 61.16 ± 4.77 a | 76.83 ± 0.84 a,b,c | 86.60 ± 6.53 a,b,c,d |

| Trabecular bone area of callus (mm2) |

7.34 ± 1.54 | 7.14 ± 1.18 | 7.19 ± 0.96 | 8.40 ± 1.85 b | 9.22 ± 2.07 b,c |

p < 0.05, versus Group I

p < 0.05, versus Group II

p < 0.05, versus Group III

p < 0.05, versus Group IV

Morphometric evaluation of the callus in the group of animals that underwent the sham operation revealed a relatively smaller callus that mainly consisted of a trabecular, woven bone network. On the other hand, the rats post-OVX with or without 17-estradiol treatment (Groups II and III) exhibited a much looser cancellous network in the callus which was more abundant in the fibrous marrow and cartilage than in the sham-operated or PTH-treated OVX group.

There were pronounced differences between saline or estrogen-treated OVX rats (Groups II and III) and PTH-treated OVX rats (Groups IV and V) in the size and structure of the external calluses. The PTH-treated animals showed a more pronounced callus formation affecting a larger area beyond the original cortex. The callus was not as loosely woven as trabecular bone of Group II or III. Specifically, the high dose PTH group was comparable to the sham group in terms of percent trabecular bone volume within the callus, and the total trabecular bone volume area of callus.

Mechanical measurements of fracture callus (Table II)

TABLE II. MECHANICAL MEASUREMENTS OF FRACTURE CALLUS.

| Group I (n=13) |

Group II (n=14) |

Group III (n=12) |

Group IV (n=13) |

Group V (n=11) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultimate load (N) |

79.73 ± 6.06 | 34.93 ± 9.57a | 36.24 ± 12.39 a | 55.08 ± 7.27 a, b,c | 70.55 ± 8.02 b,c,d |

| Deflection (mm) |

0.21 ± 0.08 | 0.35 ± 0.15 a | 0.31 ± 0.17 | 0.25 ± 0.09 | 0.27 ± 0.14 |

| Absorbed energy (N ∙ mm) |

10.60 ± 3.47 | 4.41 ± 1.46 a | 4.59 ± 2.34 a | 4.72 ± 2.00 a | 8.32 ± 1.20 b,c,d |

| Ultimate stiffness (N / mm) |

51.15 ± 12.49 | 23.45 ± 6.84 a | 27.69 ± 9.43 a | 34.17 ± 12.90 a | 42.67 ± 19.52 b |

| Ultimate stress (N / mm2) |

37.94 ± 5.32 | 16.10 ± 2.90 a | 15.70 ± 2.34 a | 19.32 ± 4.02 a | 31.18 ± 2.52 b,c |

p < 0.05, versus Group I

p < 0.05, versus Group II

p < 0.05, versus Group III

p < 0.05, versus Group IV

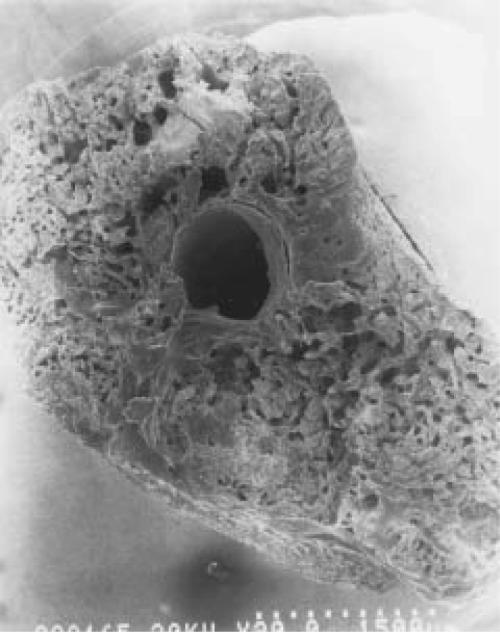

The specimens tested mechanically all failed at the original fracture site. Mechanical testing indicated that PTH administration resulted in an increase in ultimate load in OVX rats, whereas no significant differences were seen between the groups injected with saline or 17- estradiol (Group I>V>IV>III=II, p<0.05). Other significant differences were in the increase in the absorbed energy and the ultimate stress of the group of saline-treated normal rats and high doses of PTH-treated OVX rats (Group I=V>IV=II=III, p<0.05). Scanning electron microscopy showed a tendency for PTH-treated rats to have more trabecular bone in their callus resulting in the increase of callus diameter and cross sectional area of the fracture than that of sham, OVX only, or OVX plus estrogen-treated groups. However, they were also more porotic than the sham operated group (Fig. 2).

Figures 2A-B.

SEM findings of fracture callus cross-section in sham-operated (a) and PTH-treated OVX rats (b). PTH-treated OVX rats have more trabecular bone in their callus than that of sham-operated group and they were more porotic than sham-operated rats.

Figure 2A.

Figure 2B.

DISCUSSION

This study confirmed earlier observations that fracture healing is impaired in the ovariectomized rat11,28,31. An inhibition of mineralized bone formation and reduction of trabecular bone formation in later stages of fracture healing have been noted in this model. Although, in our study, there were no significant differences in external callus diameter between the sham (Group I) and the OVX-only group (Group II), Group II rats tended to have larger diameters of callus which also showed poorer bone formation in the callus than in the sham group. Many studies showed that ovariectomy in mature female rats results in an increase in transient periosteal and endosteal bone formation, which then exhibits a time-related decline5,15. As we only observed the end of the callus phase, it is uncertain that our findings are a consequence of an increase in periosteal bone formation and possibly a small increase in endosteal bone formation at early times postovariectomy, or are a characteristic pattern of fracture repair found in OVX rats.

The primary question addressed in this study is whether PTH improves fracture repair in OVX rat model. Our results demonstrated that intermittent PTH administration increased the morphometric and mechanical parameters of fracture callus. PTH is commonly believed to trigger the catabolism of bone by stimulating osteoclastic resorption. On the other hand, intermittent administration of PTH has been found to stimulate bone formation in many human and animal studies. In human studies, reported side effects have been confined to transient reddening around the injection site and transient elevation of plasma calcium above the upper limit of normal at about 6 hours after injection. The mechanism behind the anabolic effect of intermittent PTH treatment is not fully understood, but most studies in rodents using PTH analogues suggest that c-AMP dependent pathways play the predominant role in mediating the osteoinductive actions of PTH6. PTH acts directly on the osteoblast by binding to membrane receptors. The resulting increased presence of secondary messengers as c-AMP, phosphoinositol metabolites and cytosolic Ca2+ may lead to cellular proliferation and differentiation. Recently, it has been suggested that the anabolic action of PTH is substituted or partly mediated via an increased synthesis of local growth factors in the bone tissues10,20. Pfeilschifter et al20 revealed that the anabolic effect of PTH on bone mass is accompanied by progressive increases in bone matrix-associated insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and PTH has no effect on circulating IGF-I. It may suggest that the increase of bone matrix IGF-I is due to the local effect of PTH on bone tissue directly rather than to an increase of circulating IGF-I. Recent studies also demonstrated regulatory roles for those local growth factors in the initiation and the development of the fracture callus. On the basis of those findings, we questioned whether PTH also enhance fracture healing.

We found that the major effect of PTH on fracture healing was an increase in the bony tissue of the fracture callus, as reflected by morphometric parameters. But as we did not make serial observations of the entire fracture healing process, we are not certain that the increase in bony callus is due to an increase in cartilaginous cell number, or due to an increase in intracellular or extracellular matrix. Although we can not clarify whether our findings resulted from increases in one of two distinct mechanisms (intramembranous bone formation and endochondral replacement), seemingly increased cross-sectional area associated with relative narrowing of the central marrow cavity of the fracture surface noted in scanning electron microscopic study in PTH-treated rats suggests both possibilities. Histologic findings and SEM also indicated that PTH-treated rats have more trabecular bone in their callus resulting in an increase of callus diameter, but remained more porotic than the sham-operated group. This fact explains the lack of significant differences in ultimate load and ultimate stress value between sham-operated and PTH-treated groups despite differences in their external callus diameter or cross-sectional area. It means a qualitative difference rather than a quantitative difference in callus tissue between groups, and that PTH treatment of the OVX rats induces increased amounts of bone tissue in their callus, but which also has the altered mechanical properties induced by ovariectomy.

From studies concerning the effects of estrogen in OVX rats, signs both of enhanced and delayed bone repair in the rats have been reported. Danielsen et al1 noted estrogen treatment of both intact and ovariectomized rats tended to reduce the rate of periosteal bone formation. Turner et al30 found transient increases in the rate of bone formation, an early effect of ovariectomy, were reversed by the administration of 17-β estradiol. Our results showed administration of 17-β estradiol, an inhibitor of bone resorption, does not significantly influence any of the parameters in question, which means estrogen offers no advantage in terms of fracture healing in OVX rats.

The development of systemic methods for the enhancement of fracture healing is attractive, but the introduction of a systemic agent that targets the fracture healing process requires a high degree of specificity and more extensive investigation. To date, no exogenously administered systemic factors or treatments have been shown to accelerate fracture healing in a reproducible manner. Based on our preclinical study, it is suggested that intermittent PTH therapy in the estrogen- deficient osteopenic state benefits fracture healing, and PTH is likely to receive increasing study on fracture repair as well as osteoporosis. Further study is needed in large animal models, and attention should be focused on the effects of different doses or duration of the drugs used, and the relationship with local growth factors.

References

- 1.Audran M, Basle M, Defontaine A. Transient hyperparathyroidism induced by synthetic hPTH(1-34) treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;64:937–943. doi: 10.1210/jcem-64-5-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bak B, Andreassen TT. The effect of aging on fracture healing in the rat. Calcif Tissue Int. 1989;45:292–297. doi: 10.1007/BF02556022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bak B, Jorgensen PH, Andreassen TT. The stimulating effect of growth hormone on fracture healing is dependent on onset and duration of administration. Clin Orthop. 1991;264:295–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bick EM. The physiology of the aging process in the musculoskeletal apparatus. Clin Orthop. 1995;316:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danielsen CC, Mosekilde L, Svenstrup B. Cortical bone mass, composition, and mechanical properties in female rats in relation to age, long-term ovariectomy, and estrogen substitution. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993;52:26–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00675623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dempster DW, Cosman F, Parisien M, Shen V, Lindsay R. Anabolic actions of parathyroid hormone on bone. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:690–709. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-6-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ejersted C, Andreassen TT, Oxlund H. Human parathyroid hormone (1-34) and (1-84) increase the mechanical strength and thickness of cortical bone in rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:1097–1101. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekeland A, Engesaeter LB, Langeland NB. Influence of age on mechanical properties of healing fractures and intact bones in rats. Acta Orthop Scand. 1982;53:527–534. doi: 10.3109/17453678208992252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frost HM, Jee WSS. On the rat model of human osteoporosis. Bone Miner. 1992;18:227–236. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(92)90809-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunness M, Hock JM. Anabolic effect of parathyroid hormone is not modified by supplementation with insulin like growth factor (IGF-I) or growth hormone in aged female rats fed on energy-restricted or ad libitum diet. Bone. 1995;16:199–207. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(94)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill EL, Kraus K, Lapierre KP. Ovariectomy impairs fracture healing after 21 days in rats. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 1995;20:230. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hock JM, Gera I, Fonseca J, Raisz LG. Human parathyroid hormone (1-34) increases bone mass in ovariectomized and orchidectomized rats. Endocrinology. 1988;122:2899–2904. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-6-2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalu DN. The ovariectomized rat model of postmenopausal bone loss. Bone Miner. 1991;15:175–192. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(91)90124-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu CC, Kalu DN. Human parathyroid hormone prevents bone loss and augments bone formation in sexually mature ovariectomized rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1990;9:973–982. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650050911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu CC, Kalu DN, Salerno E, Echon R, Hollis BW, Ray M. Preexisting bone loss associated with ovariectomy in rats is reversed by parathyroid hormone. J Bone Miner Res. 1991;6:1071–1080. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650061008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller SC, Bowman BM, Miller MA, Bagi CM. Calcium absorption and osseous organ-, tissue-, and envelope-specific changes following ovariectomy in rats. Bone. 1991;12:439–446. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(91)90033-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosekilde L. Assessing bone quality - animal models in preclinical osteoporosis research. Bone. 1995;17:343s–352s. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosekilde L, Danielsen CC, Sogaard CH, McOsker JE, Wronski TJ. The anabolic effects of parathyroid hormone and cortical bone mass, dimensions and srength-assessed in a sexually mature, ovariectomized rat model. Bone. 1995;16:223–230. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(94)00033-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oxlund H, Ejersted C, Andreassen TT, Torring O, Nilsson MHL. Parathyroid hormone (1-34) and (1-84) stimulate cortical bone formation both from periosteum and endosteum. Calci Tissue Int. 1993;53:394–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pfeilschifter J, Laukhuf F, Muller-Beckmann B, Blum WF, Pfister T, Ziegler R. Parathyroid hormone increases the concentration of insulin- like growth factor-I and transforming growth factor beta 1 in rat bone. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:767–774. doi: 10.1172/JCI118121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reeve J. PTH: A future role in the management of osteoporosis ? J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:440–445. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650110404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reeve J, Davies UM, Hesp R, McNally E, Katz D. Treatment of osteoporosis with human parathyroid peptide and observations on effect of sodium fluoride. Br Med J. 1990;301:314–318. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6747.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reeve J, Meunier PJ, Parsons JA. Anabolic effect of human parathyroid hormone on trabecular bone in involutional osteoporosis: a multicenter trial. Br Med J. 1980;280:1340–1344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.280.6228.1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reeve J, Williams D, Hesp R, Hulme P, Klenerman L. Anabolic effects of low doses of a fragment of human parathyroid hormone on the skeleton in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Lancet. 1976;1:1035–1038. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)92216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siver JJ, Einhorn TA. Osteoporosis and aging. Clin Orthop. 1995;316:10–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tada K, Yamamuro T, Okamura H, Kasai R, Takahashi HE. Restoration of axial and appendicular bone volumes by hPTH in parathyroidectomized and osteopenic rats. Bone. 1990;11:163–169. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(90)90210-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tam CS, Heersche JNM, Murray TM, Parsons JA. Parathyroid hormone stimulates the bone apposition rate independently of its resorptive action. Endocrinology. 1982;110:506–512. doi: 10.1210/endo-110-2-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsahakis PJ, Martin DF, Harrow ME, Kiebzak GM, Meyer RA., Jr Ovariectomy impairs femoral fracture healing in adult female rats. Trans Orthop Res Soc. 1996;21:624. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tonna EA, Cronkite EP. Changes in skeletal proliferative response to trauma concomitant with aging. J Bone and Joint Surg. 1962;44-B:1557–1568. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner RT, Vandersteenhoven JJ, Bell NH. The effects of ovariectomy and 17- estradiol on cortical bone histomorphometry in growing rats. J Bone Miner Res. 1987;2:115–122. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh WR, Sherman P, Howlett CR, Sonnabend DH, Ehrlich MG. Fracture healing in a rat osteopenia model. Clin Orthop. 1997;342:218–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitfield JF, Morley P. Small bone-building fragments of parathyroid hormone: New therapeutic agents for osteoporosis. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:382–386. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitfield JF, Morley P, Ross V, Isaacs RJ, Rixon RH. Restoration of severely depleted femoral trabecular bone in ovariectomized rats by parathyroid hormone (1-34) Calcif Tissue Int. 1995;56:227–231. doi: 10.1007/BF00298615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wronski TJ, Yen CF. Anabolic effects of parathyroid hormone on cortical bone in ovariectomized rats. Bone. 1994;15:51–58. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(94)90891-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]